Zoroastrianism has a long oral tradition. Its prophet Zarathushtra (known in the West as Zoroaster) lived before the Iranians knew of writing, and for many centuries his followers refused to use this alien art for sacred purposes. The Avesta, their collection of holy texts, was finally set down in a specially invented alphabet in the fourth/fifth centuries CE. Its language, known simply as Avestan, is otherwise unrecorded. The small corpus of ‘Old Avestan’ texts is attributed to the prophet himself, and consists of the seventeen Gathas (hymns), Yasna Haptanhaiti (‘Worship of the Seven Chapters’, a short liturgy accompanying the daily act of priestly worship), and two very holy manthras.1 All ‘Young Avestan’ texts are the composite works of generations of anonymous priestly poets and scholars. The whole Avesta was written down in Iran, under the Sasanian dynasty, and was then a massive compilation in twenty-one books. Only a few copies were made, and in the destruction which later attended the Arab, Turkish and Mongol conquests of Iran all were destroyed. The surviving Avesta consists of liturgies, hymns and prayers. The manuscript tradition goes back to Sasanian times, but the oldest existing manuscript was written in 1323 CE. The Avesta has been printed [13], and translations exist in German, French, English, Gujarati and Persian.2 None can be regarded as authoritative, since research is still constantly producing new insights.

Some Avestan manuscripts have a running translation in Pahlavi, known as the Zand or ‘Interpretation’. Pahlavi, the language of Sasanian Iran, was written in a difficult script. There exist in Pahlavi translations and summaries of lost books of the Sasanian Avesta, and also a considerable secondary religious literature [5]. This too is mostly anonymous. Almost all Pahlavi works have been edited and translated, but some of the translations badly need revision.3 The later religious literature is in Persian, Gujarati and English.

The internal evidence of the Old Avestan texts shows that Zoroaster lived before the Iranians conquered the land now named after them, probably, that is, around 1200 BCE [8: 27–51]. The Iranians then, as settled pastoralists, inhabited the inner Asian steppes east of the Volga. The prophet succeeded in converting one of the tribal princes, Vishtaspa, and saw his faith take root. It spread among the eastern Iranians, and eventually reached western Iran, which had been settled by the Medes and Persians (see figure 4.1). It became the state religion of the first Persian empire (550–331 BCE), founded by Cyrus the Great, its western priests being the famed magi [3]. Its doctrines had great influence then on some of the Persians’ subjects, notably the Jews. Direct evidence for Zoroastrian beliefs and practices at this time comes mainly from Persian monuments and inscriptions and from Greek writings. The conquest of the empire by Alexander seems to have done much harm to the oral tradition, with sacred texts being lost through the deaths of priests.

In due course the Parthians, a people of north-eastern Iran, founded another Iranian empire (c.129 BCE–224 CE), which again had Zoroastrianism for its state religion [9: 78–100]; and this was succeeded by the second Persian empire, that of the Sasanians. They created for the faith a strong ecclesiastical organization, with a numerous priesthood and many temples and colleges [9: 101–44]. With the Arab conquest in the seventh century Islam supplanted Zoroastrianism as the state religion of Iran, but it was some 300 years before the Semitic faith became dominant throughout the land.

According to tradition, it was towards the end of the seventh century that a group of Zoroastrians sailed east in search of religious freedom, settling eventually, in 716, at Sanjan in Gujarat. Others joined them there, forming the nucleus of the ‘Parsi’ (Persian) community of India. For generations the Parsis prospered only modestly, as farmers and petty traders, spreading northward along the coast as far as Broach and Cambay. But from the seventeenth century, with the coming of European merchants, they advanced rapidly, and by the nineteenth century individuals had amassed huge fortunes. By contrast, the mother-community in Iran (then concentrated around the desert cities of Yazd and Kerman) was enduring ever greater poverty and oppression. The Parsis played a notable part in the development of Bombay, and by the twentieth century had become a predominantly urban community, with a well-educated middle class. Partly through their help the Iranis were freed from persecution and were able to follow suit, with a thriving community developing in Tehran. With the end of British rule in India in 1947 a number of Parsis settled abroad, notably in cities in England, Canada, Australia and the United States, and increasingly, after the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979, Iranian Zoroastrians joined them. Although prosperous, the community is numerically very small (see figure 4.2).

The Zoroastrians, enclosed as tiny minorities within Muslim and Hindu societies, were unknown to Western scholars until the seventeenth century, when merchants and other travellers brought back accounts of them. In 1700 an English divine, Thomas Hyde, published a study in Latin of the religion, drawing on these accounts and on meagre literary sources. He respected Zoroaster as a great seer and tried to prove that he had been a strict monotheist, and that Greek evidence about his dualism was misleading. In the eighteenth century a French scholar, Anquetil du Perron, travelled to India and persuaded a Parsi priest to part with Avestan and Pahlavi manuscripts, and to teach him how to read them. His published translations startled Europeans, since they gave evidence not only of dualism, but of the worship of many divine beings through intricate rituals [9]. Most were unwilling to abandon Hyde’s interpretation, and so they concluded that Zoroaster’s followers must have distorted their prophet’s teachings. This theory was strengthened when it was discovered through linguistic studies of the Avesta that the Parsi priests no longer fully understood their holy texts. This was especially true of the Gathas, which present enormous difficulties. In the mid-nineteenth century a German philologist, M. Haug, realized that these hymns were the actual words of Zoroaster. (It was more than another century before the Yasna Haptanhaiti was also recognized to be by him.) Because of their many obscurities it was possible at that stage to interpret the Gathas very freely, so owing to his preconceptions Haug translated them in a way that supported the idea of Zoroaster’s strict monotheism and rejection of rites [15]. Thereafter the theory that all the remaining Avestan and Pahlavi texts represented a corruption of the prophet’s teachings became for a long time the dominant academic dogma in the West.

In the twentieth century a Swedish scholar, H. S. Nyberg, influenced by ethnographic studies, suggested that Zoroaster had been a ‘shaman’, who composed his hymns in inspired trances [26]; and a Frenchman, G. Dumézil, sought to apply to Zoroastrianism his idea that Indo-European peoples grouped their gods according to three ‘functions’, corresponding to the social roles of priest-king, warrior and farmer. Much scholarly energy was spent on working out this theory, without generally convincing results. (For an application of his theories to Zoroastrianism see [12: 38ff.])

Rural and urban distribution of population of India (1961)

Comparison of Parsl population growth in decades

Parsis in Bombay city, percentage compared with that for all India

Meanwhile, some scholars who visited the Parsis were impressed by their high ethical standards and philosophy of life, which seemed to accord with Gathic teachings; and they began to question whether there could really have been a serious break in the tradition. Then philologists discovered allusions to existing beliefs and practices in the Gathas themselves, as their vocabulary and style became better understood. The case was thus slowly built up for regarding the Zoroastrians as having been, in fact, strikingly steadfast – as having maintained over three millennia an unbroken tradition, handed down by precept and practice as much as by holy texts. Earlier interpretations of the history of the faith had prevailed too long, however, to be easily discarded, and they still claim their adherents.

Another problem dividing scholars was the date of Zoroaster. Certain Pahlavi texts yield a date for him equivalent to 588 BCE, and in the absence of any other firm tradition this was accepted by a number of Western scholars, while as many others maintained that it was far too late to be authentic. A convincing case has by now been made for its being wholly artificial, evolved among the Greeks in connection with the fiction that Pythagoras studied astronomy with Zoroaster, and calculated evidently after the establishment of the Seleucid era (312/311 BCE) [21]. It was then evidently adopted by some Persian Zoroastrian scholastics.

Inhabitants of vast empty steppes, the Iranian priests evolved a severely simple creation myth [2: 130ff, 192ff; 9: 19ff]. They saw the world as having been made by the gods, from formless matter, in seven stages: first the ‘sky’ of stone, a firm enclosing shell; then water, filling the bottom of this shell; then earth, lying on the water like a great flat dish; then at its centre the original Plant, and then by it the uniquely created Bull, and the First Man, Gayo-maretan (‘Mortal life’); and finally the sun, representing the seventh creation, fire, which stood still above them. Fire was thought to be present too in the other creations, as a hidden life-force. Then the gods made sacrifice. They plucked and pounded the Plant and scattered its essence over the earth, and other plants grew from it. They slew the Bull and Gayo-maretan, and from their seed sprang other animal and human life. Then a line of mountains grew up along the rim of the earth, and at the centre rose the Peak of Hara, around which the sun began to circle, creating night and day. Rain fell, so heavily that the earth was broken into seven regions (karshvars). Humankind lives in the central region, cut off by seas and forests from the other six. One great sea, called Vourukasha (‘Having many bays’), is fed by a huge river which pours down ceaselessly from the Peak of Hara (see figure 4.3). These final details the priestly thinkers evidently took from still more ancient myths, while the threefold sacrifice reflected the three offerings they themselves once made, of a pounded plant (haoma), cattle and human victims. Their belief, it seems, was that as long as men continued pious sacrifices and worshipped the gods the world would endure, governed by the principle of asha. This represents order in the cosmos and justice and truth among men. As well as venerating ‘nature’ gods, the Iranians worshipped three great ethical beings whom they called the Ahuras (‘Lords’): Ahura Mazda, Lord of Wisdom, and beneath him Mithra and Varuna, Lords of the covenant and oath which, duly kept, bound men together according to asha.

Figure 4.3 The Iranian world picture

Zoroaster was himself a priest, born into this hereditary calling; but in his lifetime, it appears from the Gathas, the long-established pastoral society of the Iranians was being shattered. The Bronze Age was then well advanced among them, and warrior-princes and their followers, equipped with effective weapons and the war chariot, were indulging in continual warfare and raiding. The prophet’s own people seem to have been victims of more advanced and predatory neighbours; and the violence and injustice which he thus saw led Zoroaster to meditate deeply on good and evil, and their origins. In due course he came to experience what he perceived as a series of divine revelations, which led him to preach a new faith. He taught that there was only one eternal God, whom he recognized as Ahura Mazda, a being wholly wise, good and just, but not all-powerful, for in his own words: ‘Truly there are two primal Spirits, twins renowned to be in conflict. In thought and word, in act they are two: the good and the bad’ (Yasna 30.3). God, that is, had an Adversary, Angra Mainyu (the Evil Spirit), likewise uncreated; and it was to overcome him and destroy evil that Ahura Mazda made this world, as a battleground where their forces could meet. He accomplished this through his Holy Spirit, Spenta Mainyu, and six other great beings whom he evoked, the greatest of the Amesha Spentas, ‘Holy Immortals’. Each of the seven protects and dwells within one of the seven creations; and each is at once an aspect of God, and, as his emanation, an independent divinity to be worshipped. Ahura Mazda is transcendent; but through the Holy Spirit he can be immanent in his especial creation, humanity. Table 4.1 gives the great heptad’s names, in the order of their creations.

| Table 4.1 The six great Amesha Spentas and Spenta Mainyu: the great heptad | ||

| Avestan (Pahlavi) | Approximate English renderings | Creation |

| 1 Khshathra Vairya (Shahrevar) | Desirable Dominion/Power | Sky |

| 2 Haurvatat (Hordad) | Wholeness/Health | Water |

| 3 Spenta Armaiti (Spendarmad) | Holy Devotion/Piety | Earth |

| 4 Ameretat (Amurdad) | Long Life/Immortality | Plants |

| 5 Vohu Manah (Vahman) | Good Purpose/Intent | Cattle |

| 6 Spenta Mainyu (Spenag Menog) | Holy Spirit | Man |

| 7 Asha Vahishta (Ardvahisht) | Best Truth/Righteousness, Order | Fire |

All those who seek to be ashavan, that is, to live according to asha, should try to bring the great Amesha Spentas into their own hearts and bodies, and should serve them by caring for their physical creations. With regard to the creation of humankind, this doctrine underlies a sustained and generous philanthropy. As for Khshathra’s creation, this came to be regarded as including metals as well as the stony sky (no firm distinction being made between metals and stone among many ancient peoples), and so he could be honoured by caring for metal in all its forms (including eventually coins, to be put to good charitable uses).

The heptad evoked the other Holy Immortals, also, like them, called yazatas, beings ‘worthy of worship’. Among them were many of the beneficent old gods, including the two lesser Ahuras. Angra Mainyu countered by bringing into being evil spirits, including the daevas, ancient amoral gods of war; and with them he attacked the good creations. By Zoroastrian doctrine it was he who destroyed the first Plant, Bull and Man, bringing death into the world, while the Amesha Spentas turned evil to good by creating more life from death. This is their function, to combat evil and strengthen good. Their creations strive instinctively to this same end, all except humans, who should do so by deliberate choice, in the light of Zoroaster’s revelation. At death all individuals will be judged. If their good thoughts, words and deeds outweigh their bad, their souls cross a broad bridge and ascend to heaven. If not, the bridge contracts and they fall into hell, with its punishments.

The ultimate aim of all virtuous striving is to bring about the salvation of this world. According to Zoroaster’s teachings, the combined efforts of all the righteous will gradually weaken evil and so bring about the triumph of the good, and this is the constant expectation of his followers. For various reasons, however [4: 382–7], another strand of belief developed, that the last days will be marked by increasing wretchedness and cosmic calamities. Then, it is generally believed, the World Saviour, the Saoshyant, will come in glory. He is to be born of the seed of the prophet, miraculously preserved within a lake, and a virgin mother. There will be a great battle between yazatas and daevas, good people and bad, ending in victory for the good. The bodies of those who have died earlier will be resurrected and united with their souls, and the Last Judgement will take place through a fiery ordeal: metals in the mountains will melt to form a burning torrent, which will destroy the wicked and purge hell. (By a later softening of this doctrine, first attested in the ninth century CE, the wicked, purified by the agony of this ordeal, will survive to joint the blessed.) The saved will be given ambrosia to eat, and their bodies will become as immortal as their souls. The kingdom of Ahura Mazda will come on an earth made perfect again, and the blessed will rejoice everlastingly in his presence.

Only one major Zoroastrian heresy is known: Zurvanism, which probably arose in Babylon (then a Persian possession) in the fifth century BCE [3: 231–42]. It was a monism, and its central doctrine was that there was only one uncreated being, Zurvan (‘Time’), father of both Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu. This was grievous heresy, since a common origin was thus postulated for good and evil. But the Zurvanites held that Zurvan, a remote god, bestowed his powers on his good son, who then created this world. Hence Zurvanites and the orthodox were able to worship together in common veneration of the Creator, Ahura Mazda, despite this basic doctrinal differnce.

A Zoroastrian has the duty to pray five times daily (at sunrise, noon, sunset, midnight and dawn) in the presence of fire, the symbol of righteousness. He prays standing, and while uttering the appointed prayers (which include verses from the Gathas) unties and reties the kusti. This is the sacred cord, which should be worn constantly. It goes three times round the waist and is knotted over the sacred shirt (sedra). Before praying, the Zoroastrian performs ritual ablutions, for the faith makes cleanliness a part of godliness, seeing all uncleanness as evil. The Zoroastrian purity laws are comprehensive but are now largely neglected by urban dwellers. Nevertheless even they abhor pollution of earth or water, and maintain the strictest cleanliness in their persons and homes. The conviction that unbelievers are necessarily unclean still operates among Parsis and prevents non-Zoroastrians entering fire-temples or being present at Zoroastrian acts of worship.

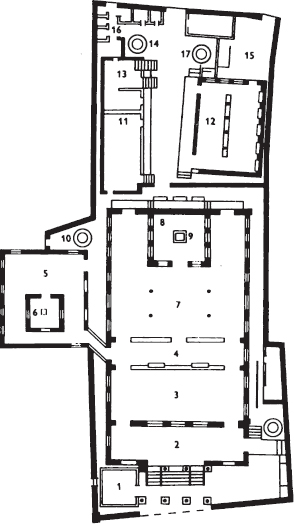

The ancient veneration of fire among the Iranian peoples evidently centred on the ever-burning hearth fire. The temple cult of fire was, it seems, instituted as late as the fourth century BCE [3: 221–5]. It, too, centres on an ever-burning wood fire, set either in the top of an altar-like pillar or in a metal vessel. There are three grades of sacred fire: the Atash Bahram (‘Victorious fire’), which is consecrated with many rites and kept blazing brightly; the Atash-i Aduran (‘Fire of fires’), more simply installed and allowed at times to lie dormant beneath its hot ashes; and the Dadgah (‘[Fire] in an appointed place’), which is virtually a hearth fire placed in a consecrated building. This may be tended, if necessary, by laypeople. There is no obligation on a Zoroastrian to visit a fire-temple, since he may pray before any ‘clean’ fire; but the sacred fires are much beloved, and in devout families children are taken to them from an early age. Some believers pray regularly at a temple (see figure 4.4), others attend only on special occasions. Some offering is always made, usually of wood or incense for the fire, with often a money gift for the priests.

Men and women have equal access to the temples, and boys and girls undergo the same initiation into the faith. This usually takes place between the ages of seven and nine among Parsis, twelve and fifteen among Iranis. The occasion, called by Iranis sedra-pushun (‘putting on the sacred shirt’), by Parsis naojote (probably ‘being born anew’), is an important family event. The child has already learnt the kusti prayers. On the day he bathes, drinks a consecrated liquid for inward cleansing and puts on the sacred shirt. The priest then performs the simple ceremony of investing him with the kusti, after which relatives dress him in new clothes and give him presents amid general rejoicing. This ceremony takes place at home or in some public hall or gardens, as do weddings. Again, before marriage bride and groom undergo a ritual purification and put on new garments. Iranis and Parsis share a common ceremony of marriage, in which Avestan and Pahlavi words are spoken by the officiating priest in the presence of assenting witnesses from the two families. Both communities have in addition a wealth of popular customs, and the festivities last several days.

Figure 4.4 Ground plan of Anjuman Atash Bahram, Bombay

N. B. On the first floor there is a hall for public events

A birth is also naturally rejoiced at, but there is then concern for purity, and in a few strictly orthodox families the mother is still segregated for forty days. Formerly the infant was given a few drops of consecrated haoma-juice soon after birth; but its naming is a simple matter of declaration by parent or priest.

Ceremonies at death are far more important and have a double aim: to isolate the impurity of the dead body and give help to the soul. The body is given into the charge of professionals, who live to some extent segregated lives, as unclean persons. Wrapped in a cotton shroud it is carried on an iron bier, after due prayers by priests, to a stone tower (dakhma), where the polluting flesh is quickly devoured by vultures and the bones are bleached by sun and wind. Mourners follow the bier at a distance, two by two, and afterwards make ablutions. Some families now prefer cremation (by electrical means), or burial, with the coffin set in cement to protect the good earth. The funeral should take place within twenty-four hours of death; but the soul is held to linger on earth for three days, during which time priests say prayers and perform ceremonies to help it. Before dawn on the fourth day family and friends gather to bid it farewell. They pray and undertake meritorious acts for its sake, for example say extra prayers or give gifts to charity. Religious ceremonies are performed for the departed soul monthly during the first year, and then annually for thirty years. After that it is held to have joined the great company of all souls, and is remembered by name at the annual feast in their honour, called by Parsis Muktad, by Iranis Farvardigan or Panje. Some of these ceremonies for the dead go back to before Zoroaster’s day, and are only uneasily reconciled with his teaching of each person’s own accountability at Judgement Day. Muktad is observed on the last five days of the year. In Irani villages the festival is still celebrated in the home, with the family priest going from house to house to bless the offerings. In urban communities the offerings are usually sent to the fire-temple, where the people gather. Zoroastrianism has ‘outer’ ceremonies, which may be performed in any clean place, and ‘inner’ ones, which may be solemnized only in a ritual precinct (usually attached to the fire-temple). To be able to perform the ‘inner’ ceremonies priests undergo an ancient purification rite (the barashnom), followed by a nine days’ retreat. Until recently some Irani villagers also tried to undergo this great cleansing at least once in their lives, and this used at one time to be the general practice.

Zoroastrianism has many holy days, joyfully celebrated. There are seven obligatory ones, traditionally founded by Zoroaster himself, in honour of Ahura Mazda and the creations. These are now known as the six gahambars and No Ruz (‘New Day’), which, celebrating the seventh creation, fire, looks forward to the final triumph of good. It is the greatest festival of the year, with communal and family celebrations, religious services, feasting and present-giving. The gahambars are now fully kept only in Irani villages, with everyone joining in five-day festivals. Among holy days which it is meritorious to keep are those of the Waters (Aban Jashan) and Fire (Adar Jashan), when many people go to pray at river-banks or the sea-shore, or at fire-temples. Through a series of calendar reforms, not universally observed, there are currently three calendars of holy days (see appendix A). In Iran an ancient tradition is maintained of seasonal pilgrimages to sacred places in the mountains, where large gatherings take place for worship and festivities. In India pilgrimages are regularly made to the oldest Parsi sacred fire at Udwada, a village on the coast.

Priests and laity remain two distinct groups, though they intermarry. Priests wear white, the colour of purity, and some Parsi laymen also do so on religious occasions. Parsi women wear the sari. In Iran, Zoroastrian village women keep a distinctive traditional dress, but in towns all Zoroastrians have now adopted standard clothing. Zoroastrian women have never worn the veil. In dietary matters their religion gives Zoroastrians great freedom, in that they are required only to refrain from anything that might belong to the evil counter-creation (e.g. a hideous fish). Under Muslim and Hindu pressures many now refrain, however, from pork and beef, and some Parsis are vegetarians by choice.

Underlying some popular customs is the belief that light is good, darkness evil. A blessing is generally murmured when a light is lit. In traditional homes the housewife would sprinkle incense on a pan of embers and carry this through all the rooms at dawn and before sunset, in purification. No cock is killed after it has begun to crow, since it is then a holy creature, announcing daybreak. Water is not drawn in villages after dark, nor money exchanged.

Other popular customs arise from respect for the creations and their immanent divinities. A flame is not blown out, but allowed to die. Care is taken not to spill anything on a fire, and if this happens, a penance is performed. Offerings are regularly made and prayers said at sources of pure water (there is one very holy well in Bombay), and in Iran noble trees are venerated. It is held a sin to cut a sapling or kill a young animal (since neither has yet fulfilled its part in the scheme of things). Animals are treated well, especially dogs. By custom, still locally observed, bread is given regularly to a dog before the family eats; and in Vahman month Hindus drive cows into Parsi quarters and the Parsis acquire merit by feeding them.

The devout feel the presence of the yazatas everywhere. In Iran at sedra-pushun a child takes one of them as its especial guardian, and individual Parsis do the same, praying often to him and lighting lamps at the fire-temple on his feast day. The Iranis have many small shrines dedicated to individual yazatas, and on great holy days will visit all the local ones, kindling fire and lamps, and offering incense and prayers. They also regularly dance and sing at the shrines, believing that gladness pleases the divine beings. There are special rites to heal the sick, to restore lost purity, or to help a woman conceive a child. When performed by priests these always include Avestan prayers, in the presence of fire; but village women sometimes perform their own rites, verging on magic, without these elements. Such practices are strongly discouraged by the community elders.

From about the ninth century Zoroastrians were cut off from contact with general advances in learning, and could do no more than practise and preserve their own faith. Increasing wealth among the Parsis did not bring any real change in this position until the early nineteenth century, when the laity were able to send their sons to Western-type schools in Bombay [17]. A Parsi priest then set up the first printing-press in that city, and Parsi newspapers were published. Soon afterwards a Scottish missionary, J. Wilson, made a determined effort to convert the Bombay Parsis, whom he admired, to Christianity. He had studied Avestan and Pahlavi texts in translation, and now made use of the new newspapers for scornful attacks on their contents, especially their dualism. The Parsi laity had had no knowledge of these ancient texts, for they themselves used their Avestan prayers as holy manthras, potent but not literally understood. So, much startled, they turned to their priests to rebut Wilson’s criticisms. But the priests, who were still trained in wholly traditional fashion, were ill-equipped to meet his challenge. One high priest simply published a restatement of orthodox beliefs, without making any attempt to reinterpret the ancient myths which they incorporated, and which Wilson had mocked; and the laity felt accordingly that he had failed them. Two other priests took refuge in occultism, interpreting the Avesta allegorically in the light of Sufi and Hindu concepts. Its ‘inner’ teachings, they declared, concerned a remote, almighty God, while ‘Ohrmazd and Ahriman’ were no more than allegories for man’s own better and worse selves. The yazatas they held to be a series of intermediate intelligences; and they found that Zoroaster had implied the doctrine of reincarnation, with salvation to be achieved by self-denial and fasting. Although all this was in fact alien to Zoroastrianism, a number of Parsis accepted it as offering an escape from the perplexities suddenly thrust upon them.

Others tried to modernize their faith more rationally; and in 1851 the Zoroastrian Reform Society was founded, ‘to break through the thousand and one religious prejudices that tend to retard the progress … of the community’. Some of its members adopted the extreme Western theory (publicized by Wilson) that Zoroaster had preached a simple monotheism, rejecting virtually all rituals; and their position was strengthened when Haug, lecturing in Bombay in the 1860s, expounded his own interpretation of the Gathas. Those who held to traditional observances received their share of Western support later, when Theosophy, with its occultism and regard for the esoteric value of rituals, was brought to Bombay from the US in 1885. A number of Parsis joined the Theosophical Society, and came into danger of adulterating their own beliefs and practices with alien (largely Hindu) ones. For this they were censured by adherents of Ilm-i Khshnoom (‘Science of (Spiritual) Satisfaction’). This is an exclusively Zoroastrian occultist movement which was founded in 1902 by an uneducated Parsi, Behramshah Shroff. He interpreted the Avesta in the light of his own visions and again taught of one impersonal God, and of planes of being and reincarnation, with much planetary lore intermixed. He showed a total disregard for textual or historical accuracy, but stressed the importance of exactly performed rituals and adherence to the purity laws. There are some Ilm-i Khshnoom fire-temples, but the movement, though it has grown, is now subdivided into contending factions.

Reformists had earlier published, in Gujarati script, cheap printed copies of the Khorda (Little) Avesta, the Zoroastrian prayer-book, so that every Parsi now had direct access to the sacred texts. This further diminished the role of the priests, who had fallen rapidly from being respected for their learning to being despised as ignorant, not only of the new secular knowledge but also of the true meaning of the holy books. The need for better understanding of the latter led a layman, K. R. Cama, to introduce their study on Western philological principles. His pupils, all young priests, worked admirably at editing and translating Pahlavi and Avestan texts, but attempted no fundamental theological studies. The Parsis, who lack any one recognized ecclesiastical authority, remained perplexed and divided into contending religious groups. The old dualistic orthodoxy persisted mostly in the small towns and villages of Gujarat, but in Bombay it was largely overlaid by declared monotheisms of either the Western or the occultist type. In the 1970s, however, a new Western respect for Zoroastrian dualism began to exert an influence, and yet another movement was launched among the laity to revive more traditional beliefs, and to reconcile ancient myths with current scientific knowledge.

From the late nineteenth century the Parsi reform movement influenced the urban community in Iran, but an unquestioning orthodoxy survived in country regions there until well into the second half of the twentieth century. In cities outside Iran and India Parsis and Iranis mingle and every shade of religious opinion is represented, together with widespread secularism. Survival of the faith is often seen as part of the preservation of communal identity, and both for this and for truly devout reasons vigorous efforts are often made locally to maintain the religious life. Special efforts are now made to publish attractive books of instruction for children, and to ensure that they are initiated into the faith. Whether those with a non-Zoroastrian mother or father may properly be admitted, or converts made, are controversial matters, discussed all the more urgently because of the community’s dwindling numbers, due both to a falling birth-rate and to absorption into surrounding societies.

Despite doctrinal confusions, the traditional moral theology can be seen still shaping the lives of Zoroastrians. Their prophet taught the need for each of his followers to be constantly active in furthering the good creation; and from the time the Zoroastrians first re-emerged into general history individuals can be seen exerting themselves to benefit others, through charitable gifts, public works, medical care and the like. Latterly they have entered local and national politics, caring thus not only for their own communities but for society at large. As three Parsis have sat in the British House of Commons [16: 69ff], and others have been active in Indian politics, so an Iranian Zoroastrian was a founding member of the first Iranian parliament, established in 1906. The strikingly parallel achievements of the two Zoroastrian communities, separated since the ninth century, and both for a long time impoverished and oppressed, appear to result from the two factors which they have in common: valiant ancestors, prepared to sacrifice almost everything for their faith; and that faith itself, demanding of them courage and integrity, love of God and their fellow creatures, and an undaunted active opposition to evil in every form.

The dynamic role of Paris traders in British India resulted in the establishment of numerous Zoroastrian centres around the world. The first Parsi known to travel overseas for trade was Naoroji Rustomji, who went to Britain in 1723 to press his family case against the injustice of British officials of the East India Company. He was vindicated and returned to India a richer and renowned man who went on to become one of his Bombay community’s leaders. From the middle of the eighteenth century Parsis were prominent in the China trade, and established formal associations in Canton, Shanghai and Hong Kong. After the 1947 Communist revolution all the communities regrouped in Hong Kong, where, at the close of the millennium, with the return of Hong Kong to China, there is a small Parsi community (approximately 150). It is a closely knit group with little cultural contact with the outside world, except back home to the old country, India, where its members have undertaken some significant charitable work. As a result of their relative cultural isolation they have generally preserved a traditional nineteenth-century code of practice and belief, relatively free from Western intellectual or religious influences.

Formal Parsi communities were established in East Africa from the 1870s, specifically in Zanzibar, Mombasa and Nairobi. They too remained culturally distanced from other communities and were thus free from modernizing Western influences, more so than the communities in India. After the Second World War all Asian communities in East Africa flourished in trade and the professions and their numbers consequently grew rapidly, including those of Parsis. By the 1960s Asians were so dominant that African jealousies were aroused and policies of Africanization followed, putting pressure on most Asians, including Parsis, to leave. A very small number went to India and a few travelled to Canada, but most moved to Britain, where their traditional staunch piety had quite an influence on the Zoroastrians already settled there.

From the mid-nineteenth century Parsis had moved from Bombay and Gujarat to Sind as middlemen in trade and as brokers and agents of the British forces [22]. They became wealthy and in the twentieth century were influential in local politics and noted for their considerable cosmopolitan charities, especially in the fields of education and medicine. As partition approached, and the Islamic nation of Pakistan emerged, some Parsis feared for their future, recalling their experiences in Iran. But others were close to the Independence leaders. Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, for example, had a Parsi mentor (Sir Pherozeshah Mehta), and a Parsi wife, and it was a Parsi doctor who cared for him in his struggle with terminal cancer during the negotiations for partition. Since 1947 several Parsis have been influential in Pakistani politics and in the diplomatic and legal professions, as well as in business. But as a more fundamentalist, or extremist, form of Islam has become vocal, a number of Parsis have migrated, fearing for their future in the old country and seeking opportunities in the West. Because of the high profile of religion in Pakistan, the level of religious knowledge, practice and commitment typical of the communities there, mainly in Karachi, has been carried westwards with migrants from that city.

The Zoroastrian community in Britain is concentrated mainly in London, which houses the largest Zoroastrian population of any city in the Western world [18]. The community was formally founded in 1861 and consisted not only of travelling businessmen but also of students, mostly of law and medicine. In 1892 and 1895 two Parsis (Dadabhai Naoroji and Sir Muncherji Bhownagree) were elected Members of Parliament at Westminster, the first Asians to hold this position. A third, Shapurji Saklatvala, was elected an MP in 1920. The majority of British Zoroastrians have their ancestry in India, though there is a substantial proportion from Pakistan. Most of them arrived in Britain in the 1960s, and later in that decade were joined by the migrants from East Africa; but approximately one-third have been born in Britain. In 1979, following the fall of the Shah and the establishment of the Islamic Republic in Iran, they were joined by a number of Zoroastrians from Iran. The British community is, therefore, a microcosm of the macrocosm of the Zoroastrian world, and subject to a whole range of internal religious pressures, with traditional, reformist, Iranian and Indian groups. Whereas outsiders and scholars in the 1960s prophesied that Asian migrants to the West would inevitably assimilate, the British Zoroastrians now have a more vigorous programme of religious ceremonies, classes and social functions than they did in the earlier years. Religion appears to be of growing importance as a marker of the community and of individual identity, despite the problems of preserving the ancient faith in the modern West when their numbers are so small – 5,000 at most.

Zoroastrian individuals settled in North America at the start of the twentieth century, but it was not until the 1960s that they came in any numbers, first from India and Pakistan, and then around 1979 from Iran [30]. The earliest associations were in Vancouver and Toronto in Canada, and Chicago and New York in the US, all in the mid-1960s. Numbers have grown steadily into the 1990s, when there were approximately 6,000 on the continent with the largest concentrations in California and British Columbia. In both of these centres there is a roughly equal mixture of Parsis and Iranian Zoroastrians. The other smaller settlements (each below 1,000), mainly Parsi-dominated, are in Washington and Houston, Texas, as well as in the older centres already mentioned. Typically the Zoroastrians in the US are highly educated scientists; in Canada almost as highly educated but more in the professions. In both countries they have developed effective infrastructures for religious education, youth groups and camps, and have established religious buildings in several cities. Over twenty formal Zoroastrian bodies in Canada and the US have grouped themselves under an umbrella body, the Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America (FEZANA), which seeks to harness the resources of the scattered groups. They are a particularly active and dynamic section of the Zoroastrian world, and may have a role in shaping the future of the religion and its teaching, although there are some tensions with traditional religious authorities in India (less so with those in Iran).

The latest destination for Parsi migration is Australia, mainly Sydney, where a purpose-built centre was opened in the 1990s, and Melbourne. Although some individuals are going in search of education, most are migrating for career opportunities. Since most Australian Zoroastrians have only recently settled there, their ties with India and Pakistan (there are relatively few Iranian Zoroastrians) are close, and some traditional voices remain influential.

Several consequences for the history of the religion arise from this dispersion. The first is the draining away from India and Iran of some outstanding talents and dynamic potential leaders, making the problem of declining numbers there even more serious. The numbers and natures of the diaspora Zoroastrians mean that important developments for the future of the religion will take place outside the old countries. As religions move from one culture to another it is natural that they should change to some extent. Christianity in Africa has altered from its European forms; and if Zoroastrianism is to be meaningful for the second and third generations of American or British or Australian believers, so its teachings and practices too may need to be adapted. Yet such adaptations are inevitably going to cause tensions with religious leaders in India. How far can a religion change yet retain its identity? These broad issues will be discussed in chapter 25 below.

The position is somewhat different for Iranian Zoroastrians. For them there is still no doubt that Iran remains their true home, even though those in the diaspora are currently reluctant to return permanently. As the third millennium approaches, more are going back for visits, so that the ties are far from broken; indeed, Iranian Zoroastrians are stronger in the retention of many of their identity markers (especially language, music and food) than the Parsis. The Iranian Zoroastrians are more concentrated in the diaspora, mainly in California and British Columbia. Many of those who remain in Iran feel vulnerable and suffer discrimination in education and careers as well as socially. But official government figures there claim that the community’s numbers are growing and those whose forebears have withstood oppression for over a millennium are likely themselves to face the future with determination to preserve the ancient religion of their prophet.

1 That Yasna Haptanhaiti is to be attributed to Zoroaster was established only late in the twentieth century. See Narten [25], and further Boyce [8: 62–100].

2 Darmesteter and Mills [10] is still the only complete English translation, but is badly in need of revision. For the Gathas it is best to look at more than one translation, e.g. Moulton [24], Duchesne-Guillemin [11], Insler [20] and Humbach [19].

3 This includes the pioneer translations of West [28], which are still valuable for their introductions and notes.

Gahambar is the Middle Persian term for six of the seven obligatory Zoroastrian festivals, neglect of which was formerly held to be a sin. The gahambars appear to have been ancient seasonal festivals, refounded (tradition says by Zarathushtra himself) to honour Ahura Mazda and the six great Amesha Spentas, together with the seven creations. Each festival probably lasted originally one day, but after a calendar reform, it seems in the later Achaemenian period, they were extended to six days, later reduced to five. The seventh festival is called in Middle Persian No Roz (‘New Day’), and celebrates the beginning of the year. The dates of the celebration of the festivals according to the three existing Zoroastrian calendars are shown in the table below.

| The seven holy days of obligation | ||||

| Dates celebrated | ||||

| Festival/Ancient name | In 1980–3 | In 1984–7 | ||

| 1 | Midspring/Maidhyoizaremaya | S | 5–9 October | 4–8 October |

| Associated ‘Holy Immortal’: | K | 5–9 September | 4–8 September | |

| Dominion | F | 30 April | 30 April | |

| Associated creation: Sky | to 4 May | to 4 May | ||

| 2 | Midsummer/Maidhyoishema | S | 4–8 December | 3–7 December |

| Associated ‘Holy Immortal’: | K | 4–8 November | 3–7 November | |

| Wholeness | F | 29 June | 29 June | |

| Associated creation: Water | to 3 July | to 3 July | ||

| 3 | Bringing in corn/Paitishahya | S | 18–22 February | 17–21 February |

| Associated ‘Holy Immortal’: | K | 19–23 January | 18–22 January | |

| Devotion | F | 12–16 September | 12–16 | |

| Associated creation: Earth | September | |||

| 4 | Homecoming (of the herds)/ | S | 19–22 March | 18–21 March |

| Ayathrima | K | 19–22 February | 17–21 February | |

| Associated ‘Holy Immortal’: | F | 12–16 October | 12–16 October | |

| Immortality | ||||

| Associated creation: Plants | ||||

| 5 | Midwinter/Maidhyairya | S | 7–11 June | 6–10 June |

| Associated ‘Holy Immortal’: | K | 8–12 May | 7–11 May | |

| Good Intent | F | 31 December | 31 December | |

| Associated creation: Cattle | to 4 January | to 4 January | ||

| 6 | All Souls (Parsi Muktad, | S | 21–25 August | 20–24 August |

| Irani Farvardigan)/ | K | 22–26 July | 21–25 July | |

| Hamaspathmaedaya | F | 16–20 March | 16–20 March | |

| Associated ‘Holy Immortal’: | ||||

| Holy Spirit/Ahura Mazda | ||||

| Associated creation: Man | ||||

| 7 | New Day/No Ruz | S | 26 August | 25 August |

| Associated ‘Holy Immortal’: | K | 27 July | 26 July | |

| Righteousness | F | 21 March | 21 March | |

| Associated creation: Fire | ||||

| ‘Old’ No Ruz (Hordad Sal, | S | 31 August | 30 August | |

| celebrated on day Hordad, | K | 1 August | 31 July | |

| see Appendix B) | F | 26 March | 26 March | |

From ancient times the Iranians had a year of twelve months with thirty days each. The Zoroastrian calendar, created in pre-Achaemenian times, was distinctive simply through the pious dedication of each day and month to a divine being. During the Achaemenian period five days were added after the last month, to make a 365-day calendar; and three extra days were devoted to ‘Ahura Mazda the Creator (Dadvah)’, making four in all dedicated to the Deity. This was probably as an esoteric acknowledgement of Zurvan, who was worshipped as a quaternity. In later usage the first of these days is named ‘Ohrmazd’, the other three ‘Dai’ (for Dadvah); the three ‘Dai’ days are distinguished by adding to each the name of the following day, e.g. ‘Dai-pa-Adar’, ‘Dai-by (the day)-Adar’. The names are given here in their Persian forms.

The thirty days

1 Ohrmazd

2 Bahman

3 Ardibehisht

4 Shahrevar

5 Spendarmad

6 Khordad

7 Amurdad

8 Dai-pa-Adar

9 Adar

10 Aban

11 Khorshed

12 Mah

13 Tir

14 Gosh

15 Dai-pa-Mihr

16 Mihr

17 Srosh

18 Rashn

19 Farvardin

20 Bahram

21 Ram

22 Bad

23 Dai-pa-Din

24 Din

25 Ard

26 Ashtad

27 Asman

28 Zamyad

29 Mahraspand

30 Aneran

The twelve months

1 Farvardin (March/April)

2 Ardibehisht (April/May)

3 Khordad (May/June)

4 Tir (June/July)

5 Amurdad (July/August)

6 Shahrevar (August/ September)

7 Mihr (September/October)

8 Aban (October/November)

9 Adar (November/December)

10 Dai (December/January)

11 Bahman (January/February)

12 Spendarmad (February/March)

Every coincidence of a month and day name was celebrated as a name-day feast. There was thus one such feast in every month but the tenth, when four feasts were celebrated in honour of the Creator, Ohrmazd. The chief name-day feasts still celebrated by the Parsis are Aban and Adar. The Iranis also celebrate the festivals of Spendarmad, Tir and Mihr with special observances.

The five ‘extra’ days

Among the Persions the five extra days at the year’s end were named after the five groups of Zoroaster’s hymns. (All but the first of these are known by the opening word of the first hymn in the group. Gatha Ahunavaiti is called after the ‘Yatha ahu vairyo’ manthra, also composed by Zoroaster, which precedes it in the liturgy.)

1 Ahunavad

2 Ushtavad

3 Spentomad

4 Vohukhshathra

5 Vahishtoisht

The gahambar of Hamaspathmaedaya is celebrated throughout these five days.

Various later calendar reforms were directed at trying to stabilize the 365-day calendar in relation to the seasons. (The ancient 360-day calendar had been adjusted from time to time by the intercalation of a whole extra month.) It is these attempts which have led to the existence of three Zoroastrian calendars today.

1 ANQUETIL DU PERRON, A. H., Zend-Avesta, Ouvrage de Zoroastre, 2 vols in 3, Paris, Tilliard, 1771

2 BOYCE, M., A History of Zoroastrianism, vol. 1, The Early Period, Leiden, Brill, 1975 (Handbuch der Orientalistik, ed. B. Spuler, I. viii. 1.2); repr. with corrs 1989, 1996

3 BOYCE, M., A History of Zoroastrianism, vol. 2, Under the Achaemenians, Leiden, Brill, 1982 (Handbuch der Orientalistik, ed. B. Spuler, I. viii. 1.2)

4 BOYCE, M., with GRENET, F., A History of Zoroastrianism, vol. 3, Under Macedonian and Roman Rule, Leiden, Brill, 1991 (Handbuch der Orientalistik, ed. B. Spuler, I. viii. 1.2)

5 BOYCE, M., ‘Middle Persian Literature’, in Iranistik, Leiden, Brill, 1968, pp. 31–66 (Handbuch der Orientalistik, ed. B. Spuler, I.iv.2.1)

6 BOYCE, M., A Persian Stronghold of Zoroastrianism, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1977; repr. Lanham, University Press of America, 1989

7 BOYCE, M., Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1984; pb Chicago University Press, 1990

8 BOYCE, M., Zoroastrianism: Its Antiquity and Constant Vigour, Columbia Iranian Lectures 7, Costa Mesa, Mazda Publishers, 41992

9 BOYCE, M., Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, London/Boston, Routledge, 1979; pb 1984

10 DARMESTETER, J., and MILLS, L. H., The Zend-Avesta, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1883–95 (Sacred Books of the East, vols 4, 23, 31); prev. publ. 1880–7; repr. Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, 1965; New York, Krishna, 1974

11 DUCHESNE-GUILLEMIN, J., The Hymns of Zarathustra (tr. M. Henning), London, John Murray, 1952 (Wisdom of the East)

12 DUCHESNE-GUILLEMIN, J., The Western Response to Zoroaster, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1958

13 GELDNER, K., Avesta: The Sacred Books of the Parsis, 3 vols, Stuttgart, Kohlhammer, 1896 (text with introduction)

14 GNOLI, G., Zoroaster’s Time and Homeland, Naples, Istituto Universitario Orientale, Seminario di Studi Asiatici, Series Minor, VII, 1980

15 HAUG, M., Essays on the Sacred Language: Writings and Religion of the Parsis, Bombay, 1862; 3rd edn, London, Trübner, 1884; 4th edn 1907; repr. Amsterdam, Philo Press, 1971

16 HINNELLS, J. R., ‘Parsis in Britain’, Journal of the K. R. Cama Oriental Institute (Bombay), vol. 46, 1978, pp. 65–84

17 HINNELLS, J. R., ‘Parsis and British Education, 1820–1880’, Journal of the K. R Cama Oriental Institute (Bombay), vol. 46, 1978, pp. 42–59

18 HINNELLS, J. R., Zoroastrians in Britain, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1996

19 HUMBACH, H., The Gāthās of Zarathushtra, 2 vols, Heidelberg, Carl Winter, 1991

20 INSLER, S., The Gāthās of Zarathustra, Leiden, Brill, 1975 (Acta Iranica, 8)

21 KINGSLEY, P., ‘The Greek Origin of the Sixth-century Dating of Zoroaster’, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, vol. 53, 1990, pp. 245–65

22 KULKE, E., The Parsees in India, Munich, Weltforum Verlag, 1974

23 MODI, J. J., The Religious Ceremonies and Customs of the Parsees, 2nd edn, Bombay, J. B. Karani’s Sons, 1937, repr. Bombay, 1986; 1st edn Bombay, British India Press, 1922, repr. New York, Garland, 1980

24 MOULTON, J. H., Early Zoroastrianism, London, Williams & Norgate, 1913; repr. Amsterdam, Philo Press, 1972; New York, AMS, 1980

25 NARTEN, J., Der Yasna Haptanhāiti, Wiesbaden, Reichert, 1986

26 NYBERG, H. S., Die Religionen des Alten Iran (tr. into German by H. H. Schaeder), Leipzig, Hinrichs, 1938; repr. Osnabrück, Zeller, 1966

27 SEERVAI, K. N., and PATEL, B. B., ‘Gujarāt Pārsīs’, Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, vol. 9, no. 2, Bombay, Government Central Press, 1899

28 WEST, E. W., Pahlavi Texts, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1882–1901, first publ. 1880–97 (Sacred Books of the East, vols 5, 18, 37, 47); repr. Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, 1965; New York, Krishna, 1974

29 WILSON, J., The Pārsī Religion: As Contained in the Zand-Avasta and Propounded and Defended by the Zoroastrians of India and Persia, Bombay, American Mission Press, 1843

30 WRITER, R., Contemporary Zoroastrians: An Unstructured Nation, Lanham, University Press of America, 1994