11

Native North American Religions

Introduction

When Europeans arrived on the American continent 500 years ago, they found people bearing the modern phase of what archaeologists have called the ‘archaic culture’. This type of culture spread from the north to the south during the climatic changes that occurred around 8000 BCE. The strength of this particular type of culture lay in a total utilization of natural resources. Agriculture made its first real impact around the beginning of this era, but even then the variegated use of natural resources did not cease, and we still find hunting and foraging together with agriculture throughout the Americas.

Throughout this long history numerous languages and cultures arose. In North America alone 200 separate languages with countless dialects were being spoken shortly before the arrival of the Europeans. Approximately 2,000 separate languages were being spoken on the whole continent, roughly equivalent to one-third of the world’s languages. The systematic study of the relationships between these languages is still in progress, but scholars have identified at least seventeen languages families as different from one another as Indo-European is from Sino-Tibetan. Furthermore, most of the 2,000 individual languages are still being spoken today.

The cultural variety of Native Americans is just as striking. Cultural diversity can even be found within common linguistic groups (such as the Athapaskans of the woodlands and the prairies). On the other hand, striking cultural similarities can be found between mutually incomprehensible linguistic groups (such as the Pueblo culture or the North-west culture). Religions have demonstrated a curious independence of their own, sometimes closely bound to localities, at other times sweeping across linguistic and cultural barriers. Examples of the latter are the newer religious movements such as the Ghost Dance among the Plains tribes and the more widespread Native American Church or the use of the sacred pipe or sweatbaths in ritual contexts. Even though religion, culture and language are intimately related to each other, various theories that attempt mechanically to equate religious types with cultural or ecological types have failed to explain the diversity.

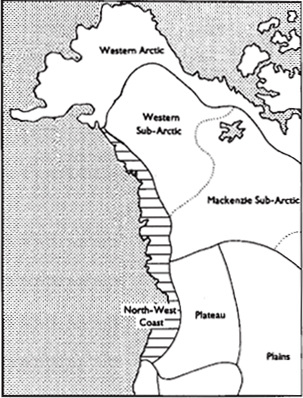

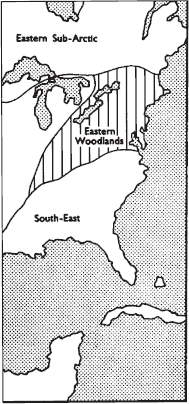

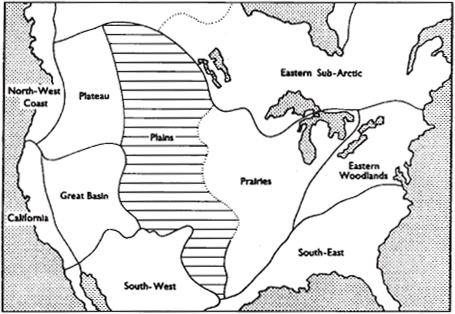

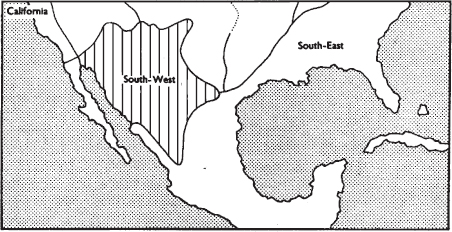

Obviously, a chapter on the religions of Native North Americans can only be selective. In what follows, characterizations of seleced groups in various regions are not meant to promote certain tribes as paradigmatic for whole regions, rather as characteristic for them. The map insets in the following pages can help give the reader a compact overview of the multiplicity of languages, cultures and religions of Native North Americans in relation to their geographical locations. The caption to each map inset contains information on examples of language families followed by examples of specific peoples. Information on the kind of technology used is followed by information on social and religious aspects of the area. I will in the following restrict this chapter to four areas: the North-west Coast, the Eastern Woodlands, the Plains and the South-west.

The Sources on Native North American Cultures and Religions

There is an enormous amount of literature on Native North America going back to the seventy-three volumes of the Jesuit Relations, produced in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The best modern overview of the sources and literature is found in Åke Hultkrantz’s book The Study of American Indian Religions [13] and in the recent multi-volume Handbook of North American Indians [34].

When the Smithsonian Institution was established in 1846, Henry R. Schoolcraft submitted his plan for the investigation of the American Indians in which all of the main concerns of later anthropology were already present, especially the importance of native folklore in its social function. During the latter half of the century, the museums became centres of anthropological activities by sponsoring fieldwork, research and publications, and thus took on the dual role of educating anthropologists as well as the public. Museums were key institutions of civil society, crucial to the production and legitimation of moral and cultural values. Today many of these same museums are struggling with difficult ethical and political issues concerning the repratriation of Native American material culture and burial remains.

All of the concerns developed during the nineteenth century were synthesized, intensified and made more scientific through the efforts of the Bureau of American Ethnology under the leadership of the great pioneer John Wesley Powell (1834–1902), but it was the World Columbian Exposition and associated Congresses in 1893 which had the greatest influence on American anthropology. A special building was built for the ethnological exhibits and named the ‘Anthropological Building’. Since that time, the word anthropology came to be used as the label for the entire study of humankind. The exhibits were grouped according to Powell’s linguistic classification to show the genetic relationships among the tribes. At the same time the arts and crafts were grouped together by natural region to demonstrate the effects of natural resources on manufacture and to show the ‘culture areas’ of the tribal groups. The theory of culture areas stemmed directly from this arrangement of museum exhibits.

By 1900 American anthropology had become an academic discipline. Franz Boas (1858–1942) introduced to anthropology rigorous standards of proof and a critical scepticism towards all generalization. He preached the radical German empiricism of his early training and disdained the use of theory, being content to collect ‘objective’ data. He substituted the historical method for the discredited comparative method of evolutionists. Boasian anthropologists have since been criticized for mostly eliciting idealized memories of what indigenous cultures had been like a generation or more before the time of fieldwork. By the end of the 1920s every major university department of anthropology was chaired by Boas’ students.

New developments in American anthropology during the 1930s and 1940s laid emphasis on the individual in relationship to his or her culture in terms of gestalt psychology, psychoanalytical conceptions and learning theory. This period also saw an increase in the biographical approach which has produced many fine studies and autobiographies of memorable Native American personalities, such as the Hopi Don Talayesva [31], the Winnebago Sam Blowsnake [28] and the Yahi Ishi [18].

The period 1930–60 witnessed the rise of social anthropology and the decline of ethnology in Britain and the US. The Second World War caused new orientations everywhere, and in the postwar US a synthesis of social and cultural anthropology developed with new relationships between the social sciences and history. Since the 1960s many superb ethnographies have been written about Native North American religions. Linguistic studies and collections of religious and mythical texts have also seen a renaissance, such as the excellent work of Ekkehart Malotki on the Hopi [21], Dennis Tedlock on the Zuni [36] and Donald Bahr on the Pima and Papago [1]. It should also be noted that important contributions to the study of Native North America have been made by distinguished European ethnographers such as Werner Müller [22], Wolfgang Lindig [19] and Horst Hartmann [8]. Now taking over their mantle are younger scholars such as Christian F. Feest [4; 5], who is the founding editor of the European Review of Native American Studies, published in Vienna.

From 1960 on there developed a sharpened awareness of the role that theory plays in scientific work, as a result of strong influences from French and German philosophy. One of these is the structuralist method introduced by the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss. Taking his point of departure in linguistic theory, Lévi-Strauss became one of the most significant interpreters of the mass of ethnographic material left by Boas and his students. His method of analysing Native American myths has demonstrated the startling complexity of indigenous classification systems, and his classic four-volume work entitled Mythologique (Introduction to a Science of Mythology in English), published between 1964 and 1971, has become a classic in his own lifetime.

The most renowned historian of religions in the study of Native North Americans is the Swedish scholar Åke Hultkrantz. Hultkrantz placed emphasis on beliefs, the ideology of rites and the function of religion [9; 10; 12]. The emphasis on beliefs and conceptions was formulated in order to counterbalance American behavioural studies.

Hultkrantz has influenced several generations of scholars in the US as well as in Europe; his American students include Joseph Epes Brown, Daniel Merkur, Guy H. Cooper, Thomas McElwain and Paul B. Steinmetz. Other historians of religions have been developing parallel or alternative strategies in the study of Native North Americans. Karl W. Luckert established the excellent bilingual text series called American Tribal Religions. Sam Gill, Christopher Vecsey and Jordan Paper have dealt with comparative issues, and I have dealt with theoretical problems in the study of Native American religions [20; 7; 25; 6].

In order to overcome insider/outsider problems, Boas encouraged educated natives to write down spontaneously in the vernacular what they knew or what they could gather from their elders. The results were many excellent bilingual collections [e.g. 14; 15; 16]. More recent scholars in linguistics have found that encouraging trained native speakers to analyse their own languages can bring rewarding results. In the field of social and cultural anthropology, there are a number of outstanding cultural informants and editors, and many Native American scholars such as the renowned Edward P. Dozier, Alfonso Ortiz and Emory Sekaquaptewa have served as mentors for generations of graduate students, both native and nonnative [see e.g. 3; 24].

Relations between Native Americans and outside scholars have not always been cordial, but the era of conventional researcher – informant relations has now ended. Not only are many native peoples tired of intruders, anthropologists especially, they have also become aware of the political and ethical impact they have on the American public. Many have university educations and are trying to help their people accommodate themselves to American society. Consequently, educated native people are demanding equal status in academic publications, and an ever-increasing number of peoples and tribes, such as the Pueblos, are claiming the exclusive right to represent their own cultures and aggressively pursue non-natives who write about them. The ‘living laboratories’ of early anthropology that spawned scholarly monographs, encouraged tourism and inspired popular culture have now become angry Native American writers. Recent examples are the outrage of the Hopis at the publication of the sensationalizing Book of the Hopi by Frank Waters during the 1960s, the official banishment of Judith Fein by the Eight Northern Pueblos for her popularizing Indian Time (1993) and the heated attack on the highly acclaimed scholarly monograph When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away by Ramón A. Gutiérrez (1991). Publications on Native American cultures are no longer just interesting additions to contemporary literature; such work has become the focus of ethical and political issues.

North-west Coast Cultures

The North-west Coast cultures extend more than 1,500 miles from Alaska to California [35; 38]. The peoples of the North-west Coast have developed a distinctive material culture which justifies a common classification. Its primary characteristic is a highly developed woodworking technology, with large plank houses, large canoes, and many types of boxes, containers, dishes, ceremonial gear and monuments such as the well-known funerary poles.

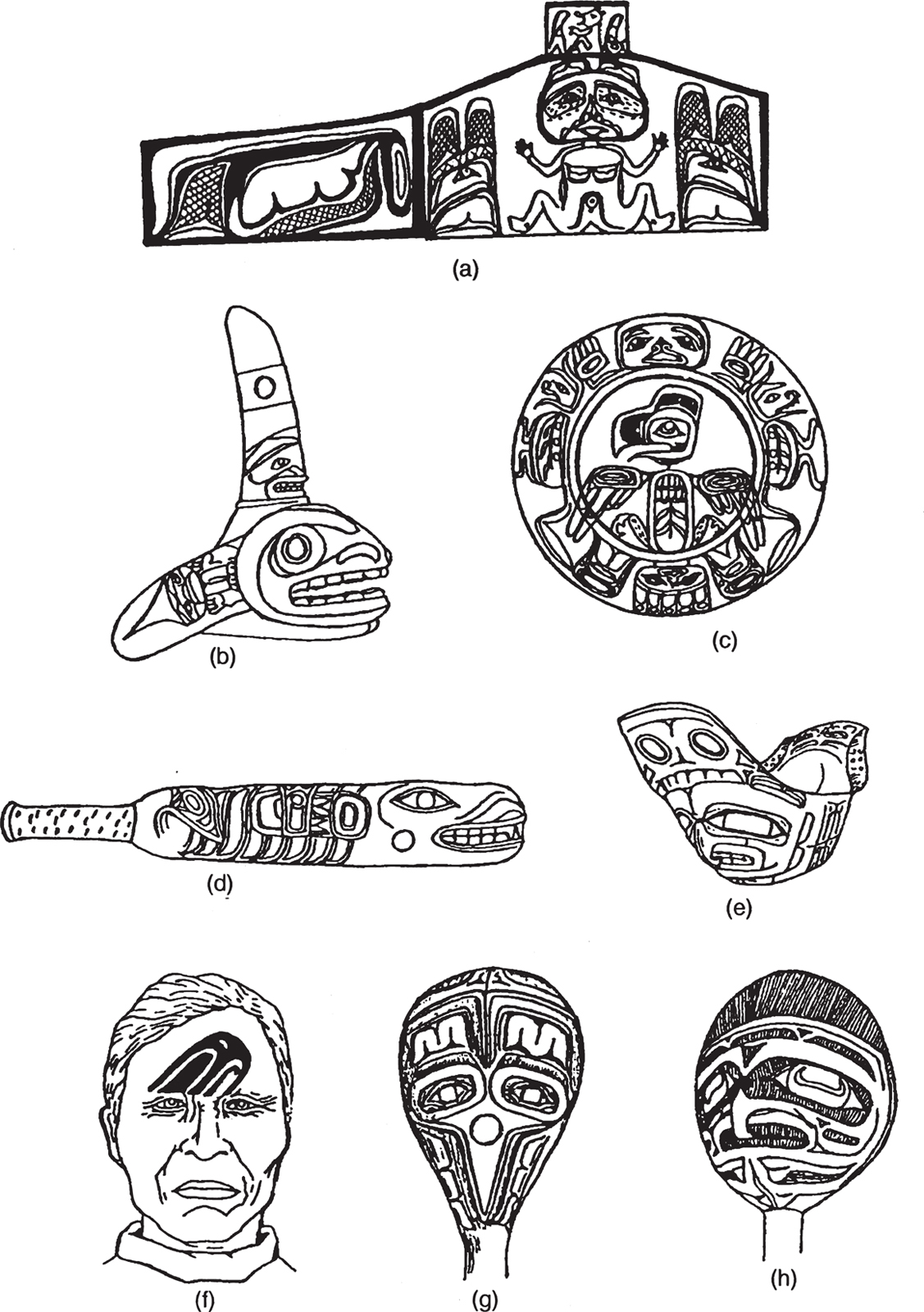

Figure 11.1 (a) Back and side of a Kwakiutl long-bench illustrating a man and a hawk. The man has animal ears and face-paint. The hawk’s head is split into two parts on either side of the man and its wing is shown along the side to the left. (b) A Tsimshian hat used during ceremonial dances. The hat is made of wood and symbolizes the killer whale. (c) A Tshimshian drumskin on which is painted an eagle simultaneously viewed from the front and sides. It is surrounded by a human-like figure also simultaneously viewed from the front and sides. (d) A Tlingit club used for killing seals and halibut. The carving represents the killer whale, the dorsal fin being bent down along the side of the body to conform to the functional requirements of the instrument. (e) Tlingit dish made of the horn of the bighorn sheep. The figure is that of a hawk. (f) Haida face-painting representing the beak of a hawk. (g) Horn spoon, tribe unknown, representing the raven. (h) Tlingit rattle with hawk head.

Source: Collage drawn by Birgit Liin, based on Franz Boas, Primitive Art, Oslo, 1927, figs 167–9, 173, 211, 218, 241, 288d.

Language families: Nadene, Penutian, Algonkin

Examples of peoples: Kwakiutl, Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Chinook, Yurok, Karok, Hupa

Technology: Sea fishing and hunting; game hunting

Religious characteristics: Hierarchical society, potlatch rituals as part of central ceremonies, hereditary shamanism, secret societies, Hamatsa ceremony to the Man Eater deity, trickster, totemism, ancestor worship, stylized iconography, fishing and hunting rituals, masks, World Renewal Ceremony

The natives first met Europeans in the late eighteenth century, but it was not until the nineteenth century that colonization, missionization and governmental coercion began to have its long-term effects on Native North-west Coast cultures. The greatest tragedy of this period came with the epidemics by which 80 per cent of the population died from smallpox, measles and malaria, brought by the Europeans. Today an estimated 100,000 people live along the North-west Coast speaking over forty-five languages belonging to thirteen different language families. Most of the languages of the southern regions were extinct by the late twentieth century and a sizeable number in the north were on the verge of disappearing until programmes of language learning were established during the 1960s.

The North-west Coast peoples live in permanent villages organized socially in three major classes: the wealthy elite, the commoners and their slaves. Class was generally a matter of birth and wealth: even slaves had a hereditary status. Principles of descent, however, vary from region to region. The elite maintained their status by their wealth, especially through the well-known extravagant gift-giving rituals called ‘potlatch’, which were held during communal ceremonies. The potlatch phenomenon has been the object of much speculation among researchers who have proposed interpretations claiming that the excessive destruction and distribution of wealth reflects, on the one hand, the exorbitance of megalomania or, on the other hand, the benign distribution of wealth and goods.

Even though rituals and beliefs among the North-west Coast peoples vary greatly, there are themes common to most of the cultures. One of the basic ideas is that humans are situated in a complex web of relationships reaching into the animated world of the physical habitat, the animals, the spirits and the dead. Life and death are in constant flux, and survival depends on ritual and kinship relations with a variety of creatures. Like prey fed upon by humans, humans are also prey to a variety of man-eating birds, animals and monsters as well as other kinds of danger. Relationships to these beings are controlled through ritual, and protection against them can be obtained through a guardian spirit, the activities of a shaman, the concerted efforts of the head of the family or village, or the ceremonies of the secret brotherhoods.

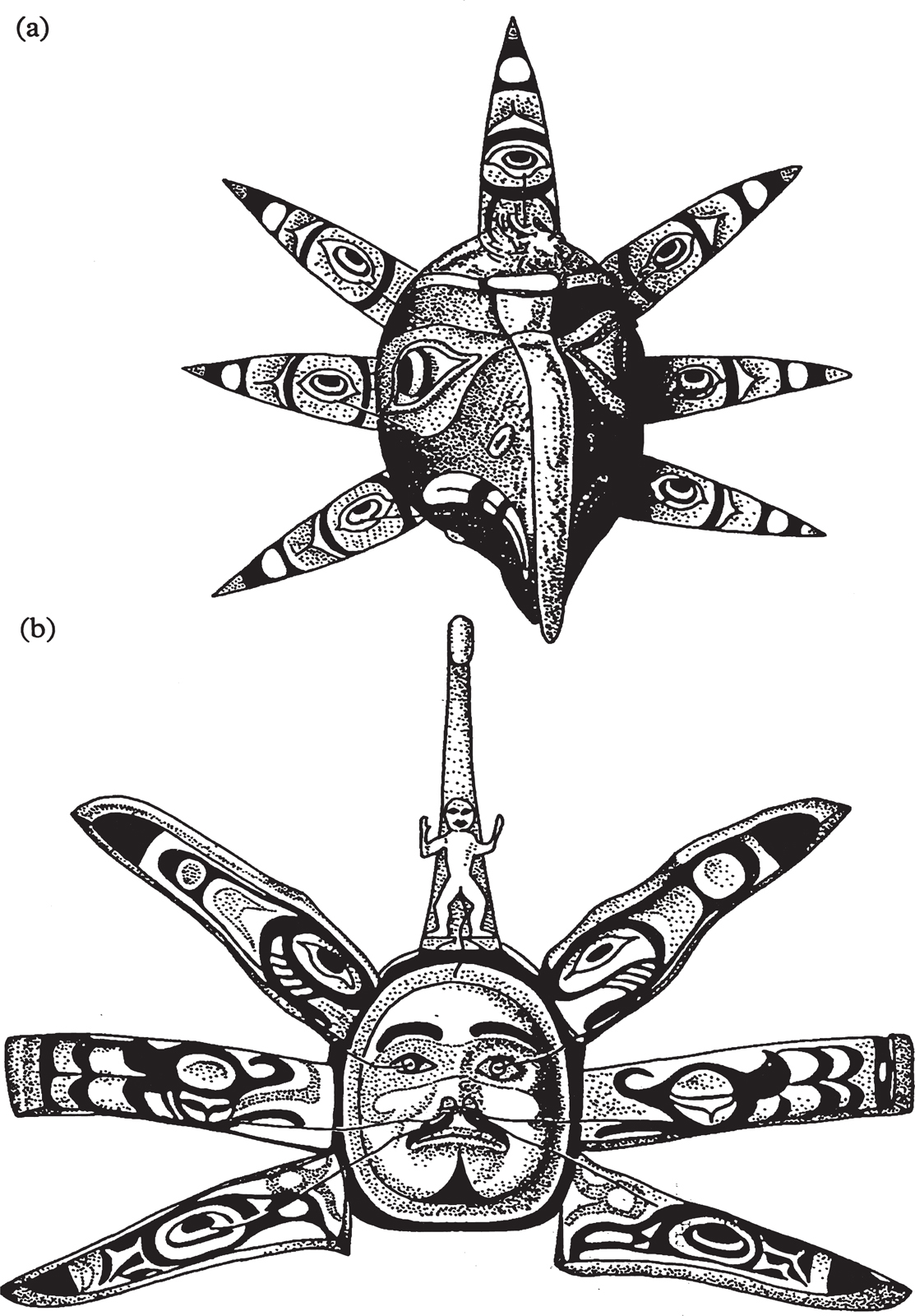

Guardian spirits are gained through fasting and isolation, and communication with them is through trance, dreams and visions. They can also possess their human partners. High-ranking social positions usually mean that the family has a special permanent relationship with a superhuman entity. Thus iconographic crests served not only as coats of arms but also as potent symbols of relationship to greater powers. Poles are raised in honour of the ancestors either in front of the family house (sometimes with the door of the house placed in the mouth or belly of one of the spirits in the family line) or as the central or corner post in the house itself, thus signifying the close relationship between pole and house, the ancestors and their living relatives. This relationship is a totemic one. The symbols also serve in ritual contexts as means of transformation. Like the flow of iconic imagery transforming the shape of one creature into another, humans could also flow into other forms. For instance, one of the crucial moments in the initiation of a new member of the Hamatsa brotherhood occurs when the initiate crawls through the mouth of the image of the Man-Eater deity. Masks play an important role in this respect, especially the so-called transformation masks. These masks are complex constructions that open up revealing not the wearer but another mask or another being inside the mask. In Kwakiutl mythology the gods use masks to transform themselves, and one myth relates that humanity came to earth as gods who took off their masks and became human.

The Kwakiutl have shamans who function just like other shamans around the world. Shamans are religious specialists who through ecstatic behaviour fly to various regions of the cosmos in order to heal the sick, divine the future and ensure the fertility of humans and animals alike. Kwakiutl shamans can be of either gender, and their helping spirits follow the family line. Shamans must follow stringent rules of behaviour and ritual, their families sometimes following them in this. Shamans wear transformation masks and costumes during their seances. With the help of their guardian spirits, they serve to heal the sick and restore souls by battling against witches and other beings who cause the illness. They also serve as intermediaries between humans and non-humans, prophesying coming events, controlling the weather, and affecting the outcome of war and the hunt. The art of transformation is their particular domain. Myths and tales are filled with descriptions of shamans and others taken prisoner by animal spirits who then become those animals and after suffering many adventures return to human society through a painful retransformation process.

Complex ceremonies are held during the winter where the origins of the clan or some other significant event are dramatically reenacted. The Kwakiutl Cedar Bark Dance can serve as an example here. This festival is the more important of the two major ceremonial complexes still practised among the Kwakiutl. Basically, the dances are re-enactments of the primordial activities of the ancestors and demonstrations of their powers. The most important spirit performed in the dance is Baxbakwalanuxsiwe, Man-Eater Spirit. A public sign that the dance is soon to be held is the sudden disappearance of a novice dancer prior to the dance. The novice or initiate is thought to have been spirited away by the Man-Eater Spirit. In the old days, when the time was right, the inviters, dressed in full ceremonial attire, sailed by canoe to the village to be invited and called upon them from the boat as the chief gave a dramatic and poetic speech. After receiving a festive meal, they sailed back home and reported dramatically on their journey. Today, however, invitations are sent on printed cards bearing crest designs.

Figure 11.3 A Kwakiutl transformation mask in (a) closed and (b) open positions. The figure in the closed position is the Thunderbird. The face in the opened position is probably the deity’s human form.

Source: Drawing by Poul Nørbo, based on Deborah Waite, ‘Kwakiutl Transformation Masks’, in Douglas Fraser (ed.), The Many Faces of Primitive Art, Englewood Cliffs, 1966, fig. 7.

The guests arrive with dramatic flair at the appointed time and are greeted with songs, dances and speeches during which many potlatch activities are performed. The ceremonial is introduced by holding a mourning ritual to clear the air of sorrow for deceased relatives of the hosts. This is followed four days later by a ritual bringing in of the ceremonial paraphernalia. Four days later, the cannibal dance is performed, during which the missing novice returns possessed by Baxbakwalanuxsiwe himself. The possessed dancer dashes about in a cannibalistic craze, apparently biting the arms of spectators and bringing everyone into intense frenzy. After his capture, the initiate then demonstrates his newly inherited dance and becomes more tame by, among other things, going through the mouth of the Man-Eater Spirit painted on the screen of the stage. Finally he is tamed and purified and returns in procession with his attendants and female relatives, thus signifying his return to the human condition.

After all the dances are completed, the goods for payment and distribution are put on display and finally distributed by rank and order, marking the end of the ceremonial. Thus ends the dramatic re-enactment of primordial times when humans, gods and animals were expressions of each other like beings wearing multiple masks. During the winter, humans pit their resources against the powers of death in order to secure the fertility and resurrection of the animal forms that must be hunted and killed during the summer months. Humans take on the masks and names of the animals during the winter and become their animal counterparts through ritual acts, thus renewing the endless cycle of reciprocity between hunter and hunted.

Eastern Woodland Cultures

It can be argued that the Eastern Woodlands constitute a single culture stretching from the southern margin of the boreal forest in Canada to the southern tip of Florida, and in the west roughly following the western borders of the Great Lakes and the eastern borders of the Prairies [37]. In this chapter the Eastern Woodlands constitute approximately the north-eastern part of the United States.

All of the tribes of the Eastern Woodlands depended on maize, hunting, fishing and foraging. The peoples around the northern regions of the Great Lakes, however, depended on gathering wild rice rather than maize horticulture. Women universally had the duty of horticulture and foraging while the men went hunting and fishing. The Atlantic seaboard cultures tended to have a pattern of seasonal movement in exploiting the rich resources of the coastal and riverine areas.

Language families: Algonkin, Hokan-Siouan

Examples of peoples: Illinois, Miami, Penobscot, Iroquois, Shawnee, Delaware, Cherokee

Technology: Hunting, agriculture

Religious characteristics: Sun gad, sacred fire ritual, sacred drink, New Year’s ceremony, sacred kingship

The archaeological record seems to indicate that the region has a long history of dynamic change. Although Europeans were in contact with the tribes of the Eastern Woodlands since 1497, they had less impact culturally and demographically than the Spaniards had on the natives of the south-east until the seventeenth century. Recent scholarship has shown that the influence of Europeans penetrated the Eastern Woodland regions before they actually appeared, resulting in the establishment of large native political organizations designed to protect territories and trade routes. However, the main experience of the peoples of the Eastern Woodlands, especially in the areas suited for agriculture, has been one of war and dislocation. This makes it difficult to reconstruct the ethnography and history of the region, and our knowledge of it is plagued by serious gaps.

Figure 11.5 The first verses of the Walum Olum

Source: Daniel G. Brinton, The Lenâpé and their Legends, Philadelphia: D. G. Brinton, 1885.

One of the most important tribes on the Atlantic seaboard was the Lenape, or the Delaware as they came to be known. They were the largest group of Algonkin speakers and lived in the valley of the Delaware River. Lenape means ‘ordinary or original person’. The Lenape consist of three tribes: the Munsee (‘person from the island’), Unami (‘person from downriver’) and Unalachtigo (translation unknown) or Unalimi (‘person from upstream’), each with its own dialect, territory and identity. Each tribe had a totemistic relation to a particular animal: Munsee the wolf, Unami the turtle and Unalachtigo the turkey. Chieftainship over the combined tribes belonged to the Unami, but this leadership was purely ceremonial in nature. Their social systems were organized into thirty-four clans, mainly with matrilineal descent patterns. They lived by hunting deer, bear and turkeys, cultivating maize, beans and squash, and fishing in both salt and fresh water, including shellfishing. They lived in multiple-family longhouses made of hickory poles and sheets of chestnut bark in stockades of logs and trees.

Religious ceremonies were usually held in the chief’s house. During puberty, young men were encouraged to fast and isolate themselves in the forest in order to attain the vision of a tutelary spirit. Dreaming about a tutelary spirit secured success in the hunt and prosperity in general. Large ceremonies were performed during the year in connection with first fruits and curing ceremonies.

The Lenape have been under continual pressure: in early times from the Iroquois and as early as the eighteenth century from Europeans. They had to flee their homeland because of war and have been displaced over great distances. The complex social and cultural changes that went with the traumas of forced travel to new and unknown regions are very difficult to follow. Thus we find Lenapes in the eastern areas producing maple syrup and in the western areas trading ginseng root for the Chinese market and hunting buffalo. Today about 4,000 Lenape live on reservations in Oklahoma (mainly Unami) and other places in the US and Ontario.

The tribal chronicle of the Lenape is recorded on several bundles of sticks engraved with 183 red pictographs called Walam Olum, ‘red paint record’ (see figure 11.5). This chronicle was first discovered by the French-born scholar Constantine S. Rafinesque around 1825, but his discovery was considered to be a hoax until later generations rehabilitated him. The pictographs are highly stylized symbols used as mnemonic devices to assist singers in remembering the five-part epic on the creation of the world, the adventures of the tutelary deity Nanabush, ‘The Great White One’ (manifesting himself as a white hare) and the wanderings of the Lenape bands and tribe. The epic is thought to have originated from a Munsee chief who received it through divine revelation.

The Lenape had a priesthood with two branches. One was called Powwow, ‘one who dreams’. Their job was to interpret people’s dreams with the help of their own tutelaries. They could also foresee the future, discern the causes of accidents and illness, and discover the whereabouts of the game animals. The other was called Medeu, ‘herbal doctor’, who were both priests and medicinemen. There was probably a third group called Gitschi achkook, ‘the great one-horned serpent’, who were wandering exorcists and also performed burial ceremonies.

In the ethics, rituals and theology of the Lenape, humans have the job of humbly following the Weelipeleexing, ‘the good (or beautiful) white path’, established for humanity by the creator Kitanitowit. The most important way to do this in recent times was to perform the annual ceremony called Ngamwin, ‘Big House Ceremony’, which developed during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries out of the aboriginal harvest and first fruits ceremonies. One of the main rituals during the Ngamwin was the treading of the symbolic white path in the ritual house. The ceremony was held in connection with the harvest in a specially built longhouse. The twelve-day ceremony consisted mainly of songs reciting the puberty visions of the men. The last day was reserved for the recitals of the women and younger men. These recitations were accompanied by processions around the centrepost to the accompaniment of the drum. Every evening ended with a festive meal. Masked dances were also performed for the guardians of the game animals.

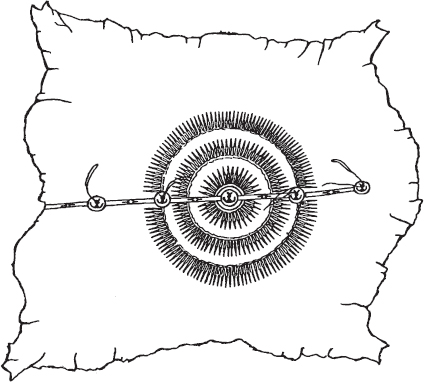

According to tradition, the Ngamwin was instituted after the Lenape were hit by an earthquake during which the earth opened and spewed black tar, smoke and steam from the underworld. Someone had a vision showing how Kitanitowit could be appeased by building the ‘Big House’ and performing the rituals of the Ngamwin. The Big House symbolized the universe in many ways. The earthen floor was the earth, the walls the four quarters, the ceiling the firmament, the space beyond the ceiling the twelve heavenly regions, the earth under the floor the Underworld, and the twelve carven masks on the walls and posts the spirits of the four quarters. The participants were the three divisions of mankind relating to the universe and its inhabitants and to the creator through the centre-pole. This pole was believed to pierce the heavenly regions and serve as the creator’s handrest. The pole was engraved with a human face said to be the image chipped into a mountainside by Kitanowit himself.

Figure 11.6 The interior of the Lenape Big House: the central pole is believed to pierce the heavenly regions, serving as a handrest for the creator whose human visage is carved into the pole. The roof is open on the left.

Source: Drawing by Armin W. Geertz based on Frank G. Speck, Concerning Iconology and the Masking Complex in Eastern North America, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, 1950, plate X.

Every action performed in the House had cosmological significance, and when the assistant priest swept the paths between the two open fires, he symbolically swept the road to heaven. The main objective was to benefit the whole world. A central ritual was the New Fire ritual in which the new, purified fire was ignited in order to renew life and secure health, long life and the general welfare of the people. Lenape ethics holds nature to be clean and without blemish. That which is given by nature to humans, such as game animals, is pure, whereas human cultural products and domesticated animals are not. By attaining a vision during puberty, humans can return to a state of purity without blemish. Each year humanity returns to this state through the celebration of those visions during the Big House Ceremony and the lighting of the New Fire. In this manner the participants become transformed into spiritual heroes singing the praises of their tutelaries.

Plains Cultures

The Great Plains cover the vast region of unbroken grassland on an elevated steppe from northern Alberta and Saskatchewan to the Rio Grande [33: 337–83; 27]. The Plains and Prairies formed the ecological frameworks for two basic types of cultures, namely the nomadic and the sedentary tribes. These cultures are found in thirty ethnic groups speaking languages from several linguistic families not restricted to the Plains. The Plains cultures developed a unique sign language which served as a lingua franca for the entire area and helped the thriving trade relations. There are today 225,000 Native Americans on the Plains.

Language families: Algonkin, Athapascan, Kiowa-Tanoan, Siouan

Examples of peoples: Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Crow, Arapaho, Teton, Pawnee

Technology: Big game (buffalo), use of horse

Religious characteristics: Buffalo altar, individual tutelary spirits, visions, medicine men, sacred bundles, sacred objects such as the arrow, pipe, spear and hat, Wakan Tanka, Sun Dance, Ghost Dance

Even though the bison is native to the Plains, and nomadic cultures have existed since the end of the Ice Age, the nomadic Plains cultures of the historic period which reached a high point by the 1850s had developed a specialized way of life centred on the bison and on a European import, the domesticated horse. The sedentary cultures, on the other hand, represented an extension of hoe horticultures developed in late prehistoric times.

The best-known nomadic Plains culture is that of the Teton or Western Sioux. The term Sioux is a French corruption of an Algonkin pejorative meaning ‘lesser, or small, adder or enemy’. The correct term is Oceti Sakowin, ‘the Seven Fireplaces’, referring to the seven divisions of the Teton who moved out of the Minnesota area on to the Great Plains in the early eighteenth century. The natives themselves, however, now use the term Sioux. The Teton belong to the largest of the Sioux divisions and are the second most populous Native American tribe in the United States, numbering today around 100,000 people. They are also called Lakota, which is the name of their dialect.

The horse nomads lived in portable skin tipis painted with symbols describing the visions and exploits of the owner. They have been regarded ever since the first contacts with the French during the seventeenth century as formidable warriors. When not engaged in war with the Algonkin tribes, they were at war with tribes belonging to the other Sioux divisions. The Teton were known as the scourge of the northern Plains, dominating the village horticulturalists and the trade of the whole area and offering armed resistance to American riverboats and wagon trains. Indeed, they are renowned for their wars and especially for the defeat of Custer’s army in 1876 and their own tragic defeat at Wounded Knee in 1890. The century of their greatness ended on reservations, where they live today, mostly in South Dakota.

Teton social organization and kinship principles are bilateral. Marriage is exogamic and residence is patrilocal. In the old days, the family lived in one or more tipis and consisted of a man, his wife or wives, unmarried children and sometimes elderly parents. Mobility for the bands or residential groups within the tribe was absolutely essential to the survival of these nomadic hunters. The patterns of fusion and fission of the bands were mostly based on affiliation with one or more men who were adept hunters and warriors. The social organization is much the same today. Chiefs are elder men elected on the basis of their achieved prominence, their maturity and judgement, and their generosity. They appoint younger leaders and soldiers to take care of the camps and enforce the resolutions of the council. When the bands gather together as a unit in camp circles during the summer months, they are under the single authority of a military society appointed for the task. The Teton also have many male and female religious and social societies.

The camp circles, or hoops, as they also are called, symbolically encircle the camp as one unit, defining the group in relation to the rest of the world. The summer camps are clearly the highpoint of the Teton year, where friends and relatives catch up on the gossip of the year and pursue matchmaking, competitive games, contests, oratory and debate and, in the old days, communal bison hunts and war parties. It is also the time to perform the great religious ceremonies under the leadership of the wicasa wakan, ‘the holy men’, those who are adept at communicating with superhuman spirits and powers.

In the following account, the religion of the Oglala is used to exemplify Teton religion. According to Oglala thought, all natural and cultural phenomena have the potential to be transformed from a secular to a sacred state. This potential is called wakan, ‘sacred’. Those who have become permanently sacred are collectively called Wakantanka, ‘Great Sacred’. Wakantanka consists of sixteen superhuman beings and powers, half of whom created the universe and the other half of whom came into existence when the earth was created. The first eight are the Sun and Moon, Sky and Wind, Earth and Falling Star, and Rock and the Thunder-being. The second eight are the Buffalo, the Bear-man, the Four Winds, the Whirlwind, the Shade, Breath, Shadelike and Potency.

There are many other superhuman beings and powers, both good and evil. Wakantanka is primarily concerned with the good aspect of universal energy, and the counterpart Wakansica, ‘Evil Sacred’, is concerned with the evil aspect. Humans may harness either aspect through propitiation of Wakantanka or Wakansica. Sacred humans gain the innate power of animate and inanimate objects through visions of superhumans and thereby gain also the ability to ward off sickness and evil. These are to be distinguished from medicine men and medicine women who heal through the use of herbal medicines. Sacred men and women serve as intermediaries, foreseeing the results of the hunt and war, or serving as instructors and interpreters of the myths, or as directors of the ceremonies. They instruct others on how to gain visions, and take on apprentices who become sacred persons in their own right.

All of the sacred ceremonies of the Oglala were given to them during a period of famine by White Buffalo Calf Woman. These consisted of seven major rituals, all of which are integrated in the symbolism of the pipe. The bowl of red stone represents the earth. It contains carvings of a buffalo calf representing four-legged animals. The stem of wood represented the flora, and the twelve feathers the eagle and winged creatures. In smoking the pipe all creatures and things are joined to the smoker. The pipe, being sacred, is handled with great care by persons fully initiated in the protocol of pipesmoking. The bowl and stem are kept separated unless in use because the potency of the assembled and loaded pipe is considerable. The pipe is smoked in a circle of seated individuals, men and women, noted for their integrity and purity. Each person smokes the pipe in turn in order to invoke the desired powers or superhuman beings.

White Buffalo Calf Woman also had a stone in her bundle with seven circles carved on it. These are the seven rites in which the pipe is to be used. The seven rituals are not the only ceremonies performed by the Oglala, but they form central themes in Oglala religion. They are the sweat lodge, the vision quest, ghost-keeping (vigil for departed relatives), the Sun Dance, the making of relatives (a type of blood-brother ritual), girl’s puberty ritual, and throwing of the ball (a religious ball game).

Figure 11.8 A typical Teton female skin cape decorated with the bursting sun motif. The motif is made of porcupine quills sewn on to the skin.

Source: Drawing by Birgit Liin based on Norman Feder, American Indian Art, New York, 1965

The Sun Dance warrants special mention. It is called Wi wanyang wacipi, ‘sun-gazing dance’ and is the only calendrical ceremonial, usually performed in June or July. The dance is under the authority of the sacred persons, and one of them is appointed Sun Dance leader. The dance itself lasts four days. The first day is spent constructing the sacred lodge around the central hole and the buffalo skull altar. The second day is spent chopping down in a careful ritual manner the tree which will serve as the central pole. The third day is spent decorating the pole with, among other things, the effigies of a man and a buffalo. It is also during the third day that the pole is placed in the central hole and raised. When this is accomplished the warrior societies dance the ‘ground-flattening dance’, during which they stamp a cross from the pole out to the four directions and shoot at the effigies hanging from the pole.

The men who have pledged to sacrifice themselves during the Sun Dance have been given instructions in a separate tipi during the first three days. They choose one of four types of sacrifice: gazing at the sun from dawn to dusk, piercing the breasts with skewers attached to the pole, piercing of the breasts and scapulae with skewers attached to rawhide ropes in order to hang suspended from four posts, and piercing of scapulae with skewers attached to thongs with one or more buffalo skulls to be dragged around the dance area. The idea of the latter three types is to dance until the flesh is torn through. They dance without food or drink all day while blowing on eagle bone whistles. Others also offer bits of their own flesh to Wakantanka while the dances go through their ordeals. After the dance is concluded, the camp circle breaks up and the paraphernalia is given away, but the lodge itself is left to deteriorate as a gift to Mother Earth.

South-west Cultures

Two things strike the mind and imagination when visiting the South-west [23]. First, one is struck by the immensity of the natural environment, its sometimes otherworldly shapes and colours, and the remarkable variety of ecological niches. Second, one is equally struck by the impressive variety of native cultures, and even more so by the fate that in spite of the violence of its contact history, the peoples of the South-west still live at or near the spots where the Spaniards found them in 1540. This continuity is reflected in the cultures down to the present day.

In 1960 there were roughly 200,000 Native Americans in north-western Mexico and the south-western US, gathered in twenty-five groups or ‘tribes’. Looking at Arizona and New Mexico alone, we find representatives of six major language families. But this language diversity did not hamper cultural exchange.

(a) Pueblos

Language families: Utaztecan, Hokan-Siouan

Examples of peoples: Hopi, Zuni, Tanoan, Keresan, Acoma

Technology: Agriculture, hunting, foraging

Religious characteristics: Creator deity and trickster, tutelary spirits, sweathouse, recitations of myths with long songs, Kuksu initiation ceremony, ceremonies for the bear and the deer

(b) Nomads

Language families: Athapaskan

Examples of peoples: Navaho, Apache

Technology: Hunting, foraging, sheep herding

Religious characteristics: Medicine men, elaborate sand-paintings, elaborate healing rituals, mountain deities, female puberty ceremony, Mountain Dance

Pueblo Cultures

The approximately 50,000 Pueblo people are divided into two major groups: the eastern Pueblos, along the Rio Grande valley, and the Western pueblos, consisting of the Zunis and the Hopis. Although there are a great many similarities in the religions of the Pueblos, the kinship, political and world-view systems can be divided into two types: (1) the bilateral type (inheritance through either line) of the eastern Pueblos, and (2) the matrilineal type (inheritance through the female line) of the western Pueblos. The bilateral type divides all of society, and ultimately the cosmos, into two equal groups. This dual system reflects itself in village planning, in governmental structure and in ceremonial system, where all facets of life operate within the boundaries of one of the two groups. The system involves the assumption of governmental and ritual responsibilities which change hands between the two groups at or near the equinoxes or the solstices. The matrilineal type rests on interrelationships between matriclans (that is, clans which calculate kinship and inheritance through the female lines) grouped into phratries (large groups of clans) and the delegation of political and religious power through cooperation between ritual brotherhoods and priesthoods.

Among all of the Pueblos, political power is an integral part of the indigenous ceremonial hierarchy. The organizations of the hierarchies were different from Pueblo to Pueblo, and from east to west, but one of the key common aspects of these organizations is that secret ritual knowledge brings social power. This can be knowledge about primordial times, insight into ritual matters, the owning of powerful songs or powerful ceremonies, knowledge about powerful beings, or other similar matters. This knowledge is revealed through a long series of initiations into ritual brotherhoods or priesthoods, and, as intimated, the most important knowledge is literally held as property – equivalent to Western notions of material possession. It is this knowledge and its practical applications which decide the order of the hierarchy. Thus, among the Hopis and the Zunis, social prestige and power are based on the order of arrival of the clans in primordial times and the particular rituals which they claim to have owned at the time.

The main focus of the ceremonial organization is the calendrical observance of large-scale dramatic ceremonies ranging from four to sixteen days in length which ensure and guard the life-cycle of the maize plant. By securing the cooperation of solar, astral and geophysical powers, the maize maintains its stages of life and death, thereby securing parallel stages in the cycles of human life and death. In a variety of ways, the metaphor of the maize plant guides the creative genius of the Pueblo people and informs the fabric of their social lives.

The Pueblo people live in a world alive with creatures of all types, from the subhuman to the superhuman, all of which are conceived of as belonging to an intricate series of reciprocal relations, where human groups are related to groups of flora and fauna, and gods, demons, and spirits claim allegiance from those who know their secrets. The worlds of these various beings are conceived of as being located in a systematic cosmos of storied worlds, one on the other, which are further divided into directional zones, sometimes four, sometimes six, usually consisting of the cardinals and the zenith and nadir. Thus, the idea of the centre or at least of a central world axis is prominent, and the whole structure constitutes a powerful frame of reference for mythical and ritual actors, as well as for the ideology of phratry and dual group relations. The Pueblo cosmos is further symbolized by the squarely built cult houses, called kivas, which represent the various underworlds that are connected by the axis, called in Hopi the Sipaapuni.

Cross-cutting the powerful clans, priesthoods, and ritual brotherhoods are other groups such as the mask cult (called by the Hopi term ‘Kachina’), ritual clown societies, curing societies, war societies and hunting societies. The Kachina Cult is the most famous Pueblo cult because of its open-air performances with dancing troupes arrayed in colourful highly codified masks and costumes. The Kachinas are ancestral spirits, some animal, some human or superhuman, whose arrivals and departures usually follow seasonal fluctuations. During these and other ceremonies, the important core narratives are told often in the form of liturgical dialogue between priests and the masked representatives of important deities. These narratives relate the story of the emergence of mankind from subterranean worlds and their migrations to the centre of this world.

Figure 11.10 Hopi Kachina dancers representing the Hemis Kachina.This Kachina opens and closes the Kachina dance season which covers the period from late winter to midsummer

Source: Photograph from the Forman Hanna collection, courtesy of the Arizona Historical and Archaeological Association, Tucson, Arizona (date and village unknown).

Against this array of societies, ceremonies and beings stand the forces of evil. The Pueblos do not conceive of any god containing the essence of evil. Some gods are more malevolent than others, but all superhuman beings are dangerous. On the other hand, the Pueblo people concern themselves mostly with human evil. A witch is by definition the exact opposite of everything that is considered sacred, good and – especially – sociable. The Pueblos do not conduct witch-hunts, but they do have specialists, such as medicine men and medicine women, who actively combat the diseases caused by witches and sorcerers and who sometimes engage in occult battles with them. Pueblo conceptions of power are such that power in itself is neither good nor evil, but becomes one or the other through usage. Thus, even medicine men or powerful priests are often suspected of using their power for sorcerous activities.

Navajo Culture

Navajo social organization and religious world-view seem to represent a bridge between the Pueblo world and the older residues of Athapaskan life. Navajos live in isolated clusters, and the fundamental principle of organization is the house, herds and fields of the resident female. Social identity is based on some sixty matriclans loosely organized in fifteen unnamed phratries. Navajo identity is further determined, even in matters of political status and leadership, by the size and appearance of the sheep herd. In earlier times, there was no clearly defined group larger than the residence group, except for loosely organized groups under the leadership of one or more headmen for dealing with outsiders.

The Navajo universe is divided into ‘holy-people’ and ‘earth-surface people’. These beings live within the confines of a circular cosmos bounded by four sacred mountains. As with the Pueblos, the Navajos believe that they too have emerged from a series of subterranean worlds, of which the present world is the fifth. But the Navajo universe is neither mythically nor socially structured in the strict hierarchy of the Pueblos.

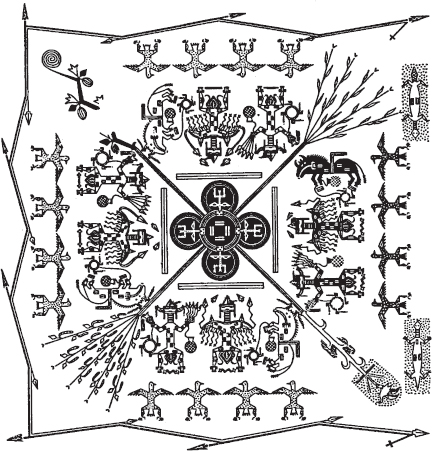

Navajo ceremonies are famous for their delicately produced sandpaintings which depict the universe in intricate symbol systems. Although this art is obviously borrowed from the Pueblos, it has none the less been refined by the Navajos. Navajo ceremonies clearly show the adoption of Pueblo ceremonies by Athapaskan shamanism. The Navajo ‘singer’ who performs complicated ceremonies over up to nine nights is a priest and not a shaman: he has learned his craft not through visions but through apprenticeship under a local singer, from whom he learns the songs, medicines, techniques and rituals. All of these matters have their source and patterns in the adventures of culture heroes or gods who have experienced misfortunes and illness, and through them have learned how to resolve such crises.

Figure 11.11 A Navajo sand-painting concerning the mythical activities of the War Twins who established the ‘Shooting Chant’ during which the sand-painting is made. The picture was revealed to the younger Twin by the Thunder People, who instructed him in its ritual use. It illustrates the watery regions of the gods and powers and the four plants – blue maize, blue beans, black squash and blue tobacco – which grow out of the lake in the centre of the painting. The painting is open to the east and is protected by the beaver and the adder.

Source: Drawing courtesy of Dover Publications, Inc., New York, from Gladys A. Reichard, Navajo Medicine Man Sandpaintings, New York, 1939, fig. 8.

The interesting thing about Navajo ceremonies as opposed to Pueblo ceremonies is that while Pueblo ceremonies address cosmic powers on behalf of communal needs and crises, Navajo ceremonies do so on behalf of only one individual patient. Thus, the elaborate sand-paintings are prepared in order to vivify and invoke the gods on the rim of the universe and to bring them to the patient who is physically placed in the centre of the painting. Contact with the gods ensures that the patient becomes sacred and strong, and when they leave, they take his or her sickness with them, after which the sand-painting is discarded in the bush. One sand-painting is made and destroyed every twenty-four hour for the duration of the healing ceremony.

A strong religious factor among the Navajos is membership in the Native American Church of North America. Its appeal did not gain force until the devastating experience of formed stock reduction by the Bureau of Indian Affairs during the 1930s. Various estimates indicate that roughly half of the Navajo population are members of the Church today. The Native American Church is a pan-Indian religious movement that combines Christian symbolism with indigenous symbols and ritualism, with the addition of the ritual eating of the psychotropic peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii), that contains among other alkaloids the well-known mescaline. Through the peyote ritual and its accompanying visions, the believer receives insight into his or her problems, as well as cures for sickness and misfortune.

Revitalization and Modern Native American Philosophy

The sources at our disposal seem to indicate a dynamic history in Native American religiosity. For instance, in the South-west we find clear indications of major influences from ancient Mexico which swept through the Pueblo areas. Even the masked Kachina rituals are a relatively recent addition to Pueblo religions. We have also seen how the invading Navajos acquired Pueblo cosmology and ritual. On the North-west Coast we find the spread of the Hamatsa ceremonial complex throughout the religions of the area. But one of the most imporant sources of religious dynamism was Christian missionizing. It is difficult to give a brief overview of the role of Christianity among Native Americans [see 39]. From John Eliot (1604–90) among seventeenth-century New England Natives to the Moravian inter-racial utopian communities among the eighteenth-century Lenape, Christianity has left its indelible mark on Native American religiosity. Many followed the traditional Christian denominations, but are now reformulating Native theologies. Even more have developed new religious movements with more or less Christian characteristics.

Generally the religious movements inspired by Christianity combine earlier shamanistic elements, the desire to return to the old ways and the hope for the return of the game animals. Most were millennial movements founded by prophetic visionaries receiving revelations from the Master of Life on how to live and what ceremonies to perform. These movements encouraged higher morals and attempted to fight poverty, alcoholism, immorality and witchcraft. Thus prophets such as the Tewa Popé (1680s; the Pueblo Rebellion), the Delaware prophet Neolin (1760), the Seneca Handsome Lake (1799), the Shawnee prophet Tenskwatawa (1811), the Salish John Slocum (1840?-1898?; Shaker), the Wanapum Smohalla (1855; the Prophet Dance), the Paiute Wodziwob (1870; the Ghost Dance), the Paiute Wovoka (1889; Ghost Dance revival), and many others demonstrate these features [11; 17]. Today many attempts to return to aboriginal religion actually constitute exercises in creative syncretism. The American Indian Movement, the Sun Dance movements and others attempt to reinstitute conceived primordial traditions.

One of the most significant developments in recent years has been that of a pan-Indian philosophy by Native American writers and thinkers. Much of it springs from romanticizations by white Americans, but there are also serious attempts to formulate an all-encompassing philosophy which has its primary frame of reference in opposition to American philosophy. It includes ideas of nature as continually unfolding, of time as being cyclical, of the presence of superhuman power, of a space – time continuum, of the elements, of metaphysical ontology, of truth based on oral tradition, of ethics based on reciprocal relations with all beings, and of trust in the truth value of dreams and visions [2; 32].

Inter-cultural Dynamics

Native Americans have long been the object of Euro-American romanticizations. Many of these can be shown to be historically false, such as the Thanksgiving story of Squanto, the supposed Indian origin of maple syrup, the idea that the Hopi language lacks abstract notions of time and space, or that Long Lance was an Indian. Similarly, the famous Black Elk was not a spokesman for traditional Lakota culture as most people think, Jamake Highwater was very likely a Greek-American film-maker, Hyemeyohsts Storm’s supposed Indian ancestry has been contested by Native Americans, and Chief Seattle, who supposedly gave the ecology speech admired and repeated by Americans and Europeans since the 1970s, never gave that speech: it was a film script written in 1970 for a film on ecology produced by the Southern Baptist Convention.

Many Euro-Americans have more or less adopted a conceived ‘Native American’ ideology as their own, enacting, as it were, their own fantasies about the Native Americans. They are jokingly called ‘Wannabes’ by Native Americans because they ‘wannabe’ Indians. The various types of Euro-American Wannabe styles are explicit identification, symbolization, creative syncretism, activism and tourism/hobbyism. The term wannabe is now also being applied to young Native Americans searching for their roots.

Native Americans have become core symbols in New Age thought and activities. This position is clearly based on Euro-American primitivism. If any one author has been an accessory to the convergence of New Age expectations with its stereotypes of Native Americans, it is Carlos Castaneda. Starting as a UCLA doctoral candidate in anthropology who was to specialize in Yaqui ethnomedicine, Carlos Castaneda at first enthralled his readers with the magic of psychotropic experiences under the expert and mysterious guidance of his Yaqui teacher don Juan Matus. Through each subsequent novel, one detects a keen attunement to the expectations of his American audience: from the use of Datura and peyote, the reader follows Castaneda’s growing maturity and his realization that don Juan’s teachings have nothing to do with drugs and everything to do with New Age ideals, i.e. a holistic world-view, strict attendance to the miraculous in nature, concerted efforts at self-development which ultimately lead to liberation even from death, and – especially in his most recent volumes – the creative manipulation of energy fields and cosmic light rays. Even though many critics have doubted the existence of don Juan and his team of ‘impeccable warriors’, he has nevertheless had an undeniable impact on the New Age public through eight volumes of powerful narrative. Castaneda became a cult figure himself, and has conducted innumerable workshops on his occultistic techniques. Many have tried to emulate his success, and some are currently challenging his integrity on the Internet and in New Age magazines, claiming that he is draining the energy of his pupils in order to pursue his own evil plans. One of Castaneda’s friends, Michael Harner, also moved from ethnography to ‘going native’ by establishing the Center for Shamanic Studies in Connecticut. His particular form of shamanic therapy has enjoyed popularity the world over. Indians have become highly marketable in New Age circles, and Harner’s White Shamanism has become a standard feature in the New Age US.

Native American reactions vary. Native American writer Wendy Rose called it another kind of cultural imperialism [29]; only this time, the imperialist is the rootless white suddenly become a presumptuous ‘expert’ through eclectic misunderstandings of Native American thought. The American Indian Movement (AIM) has responded with hostility to the New Age use of Native American culture. The Traditional Elders Circle has also condemned the exploitation of their sacred symbols. Their anger is especially directed towards ‘shamanistic’ courses and courses in ‘Native American’ rituals. But not all Native Americans feel that way. An interesting modem phenomenon is that of well-educated younger Indian shamans, ‘the New Native Shamans’, as they are called. Leslie Gray from the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco and Native American Studies Department at the University of California in Berkeley combines many ideals and professions: a university professor, shamanistic consultant, healer, shaman, sophisticated and young. She represents a new generation of Native Americans who have lost their traditional roots and yet function as bridge-makers between two worlds. Leslie Gray’s therapy is called ‘self-help shamanism’ in which she teaches her patients how to enter altered states of consciousness and to travel to the upper and/or lower worlds in order to gain information, health, or personal empowerment [30].

Will the religions of Native Americans withstand the contemporary wave of New Age missionization? I believe they will. Native Americans have withstood 500 years of European domination in each their own way, and they will most likely continue to do so. Perhaps the greatest threat to their native lifestyles and world-views is posed by agents beyond the control of even the mightiest, namely, television, videos, technology, American and world economy, the English language, and American habits of food, clothing and lifestyle. These favors will be crucial in the development of Native American religions and cultures in the coming millennium.

Bibliography

1 BAHR, DONALD M., et al., Piman Shamanism and Staying Disease, Tucson, University of Arizona Press, 1981

2 CALLICOTT, J. BAIRD, In Defense of the Land Ethic: Essays in Environmental Philosophy, Albany, State University of New York Press, 1989

3 DOZIER, EDWARD, The Pueblo Indians of North America, New York, Holt, Rinehart &Winston, 1970

4 FEEST, CHRISTIAN F., Indians and Europe: An Interdisciplinary Collection of Essays, Aachen, Rader Verlag, 1987

5 FEEST, CHRISTIAN F., Native Arts of North America, London, Thames & Hudson, 1980

6 GEERTZ, ARMIN W., The Invention of Prophecy: Continuity and Meaning in Hopi Indian Religion, Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1992, 1994

7 GILL, SAM, Mother Earth: An American Story, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1987

8 HARTMANN, HORST, Kachina-Figuren der Hopi-Indianer, Berlin, Museum für Völkerkunde, 1978

9 HULTKRANTZ, ÅKE, Belief and Worship in Native North America (ed. Christopher Vecsey), Syracuse, Syracuse University Press, 1981

10 HULTKRANTZ, ÅKE, Conceptions of the Soul among North American Indians, Stockholm, Ethnographical Museum, 1953

11 HULTKRANTZ, ÅKE, ‘Ghost Dance’, in Lawrence E. Sullivan (ed.), Native American Redigions: Nosh America, New York, Macmillan, 1987, 1989, pp. 201–5

12 HULTKRANTZ, ÅKE, The North American Indian Orpheus Tradition, Stockholm, Ethnographical Museum, 1958

13 HULTKRANTZ, ÅKE, The Study of American Indian Religions, Chico, CA, Scholars Press, 1982

14 HUNT, GEORGE, and BOAS, FRANZ, Kwakiutl Texts, 2 vols, New York, Memoirs of the American Museum of National History, 5 and 10, 1902–5, 1906

15 JONES, WILLIAM, Fox Texts, New York, American Ethnological Society Publications, 1, 1907

16 JONES, WILLIAM, Ojibwa Texts, New York, American Ethnological Society Publications, 7, 1917–19

17 JORGENSEN, JOSEPH G., ‘Modern Religious Movements’, in Lawrence E. Sullivan (ed.), Native American Religions: North America, New York, Macmillan, 1987, 1989, pp. 211–17

18 KROBER, THEODORA, Ishi in Two Worlds: A Biography of the Last Wild Indian in North America, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1961

19 LINDIG, WOLFGANG, Geheimbünde und Männerbünde der Prärie- und der Waldlandindianer Nordamerikas, Wiesbaden, Franz Steiner, 1970

20 LUCKERT, KARL W., Coyoteway: A Navaho Holyway Healing Ceremonial, Tucson, University of Arizona Press, 1979

21 MALOTKI, EKKEHART, and TALASHOMA, HERSCHEL, Hopitutuwutsi Hopi Tales: A Bilingual Collection of Hopi Indian Stories, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1978

22 MÜLLER, WERNER, Die Religionen der Waldlandindianer Nordamerikas, Berlin, Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 1956

23 ORTIZ, ALFONSO, Southwest, Washington, DC, Smithsonian Institution, 1979, 1983 (Handbook of North American Indians, vols 9, 10)

24 ORTIZ, ALFONSO, The Tewa World: Space, Time, Being and Becoming in a Pueblo Society, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1969

25 PAPER, JORDAN, Offering Smoke: The Sacred Pipe aid Native American Religion, Moscow, University of Idaho Press, 1988

26 POWERS, WILLIAM K., The Oglala Religion, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1975, 1982

27 POWERS, WILLIAM K., ‘The Plains’, ‘Lakota’, in Lawrence E. Sullivan (ed.), Native Americas Religions: North America, New York, Macmillan, 1987, 1989, pp. 35–43

28 RADIN, PAUL, The Autobiography of a Winnebago Indian, Los Angeles, 1920; repr. New York, Dover, 1963

29 ROSE, WENDY, ‘Just What’s All This Fuss about Whiteshamanism Anyway?’, in Bo Schöler (ed.), Coyote Was Here: Essays on Contemporary Native American Literary and Political Mobilization, Aarhus, University of Aarhus, 1984, pp. 13–24

30 SHAFFER, CAROLYN R., ‘Dr Leslie Gray, Bridge between Two Realities’, Shaman’s Drum, vol. 10, 1987, pp. 21–8

31 SIMMONS, LEO W. (ed.), Sun Chief: The Autobiography of a Hopi Indian, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1942

32 SIOUI, GHORGES E., For An Amerindian Autohistory: An Essay on the Foundations of a Social Ethic, Montreal, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1992

33 SPENCER, ROBERT F., and JENNINGS, JESSE D., The Native Americans: Prehistory and Ethnology of the North American Indians, New York, Harper & Row, 1965

34 STURTEVANT, WILLIAM C. (ed.), Handbook of North American Indians, 20 vols, Washington, DC, Smithsonian Institution, 1978–

35 SUTTLES, WAYNE (ed.), Northwest Coast, Washington, DC, Smithsonian Institution, 1990 (Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 7)

36 TEDLOCK, DENNIS, Finding the Center: Narrative Poetry of the Zuni Indians, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1978

37 TRIGGER, BRUCE G. (ed.), Northeast, Washington, DC, Smithsonian Institution, 1978 (Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15)

38 WALENS, STANLEY, ‘The Northwest Coast’, in Lawrence E. Sullivan (ed.), Native American Religions: North America, New York, Macmillan, 1989, pp. 89–98

39 WASHBURN, WILCOMB E. (ed.), History of Indian – White Relations, Washington, DC, Smithsonian Institution, 1988 (Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 4)