13

African Religions

Introduction

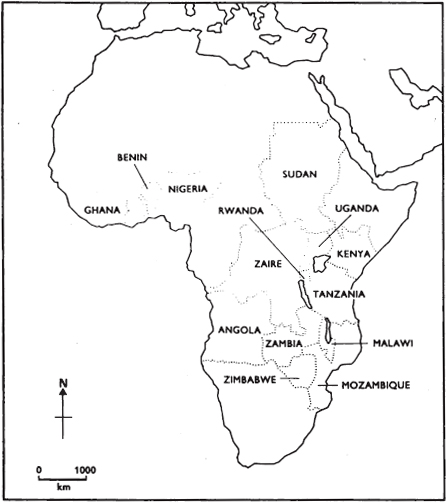

The term ‘African religions’ is used here to refer to the indigenous, ethnic religions of sub-Saharan Africa. The concept of tribe or ethnic group is a fluid one in Africa, for ethnic identities shade into one another and there have been continual migrations and amalgamations throughout African history. Basically the tribe is a category of interaction among heterogeneous peoples, but it has a cultural core which consists of a human tradition in a given physical environment. Such an environment offers a limited number of choices for solving the problems of daily living and each society has developed its social and cultural institutions in accordance with a chosen economy. Within the framework provided by physical environment and human tradition, African societies have interrogated human existence, have developed their own religious imagery and symbolic classifications and have evolved their own organic universe. Any attempt to classify the tribes of Africa is necessarily arbitrary. One such attempt has been that of G. P. Murdock, who lists 742 sub-Saharan tribes [22]. This conservative estimate conveys some idea of the size and complexity of the subject.

Nevertheless, indigenous religion in Africa is not strictly identifiable with the tribe, however it is defined, even though beliefs and values are articulated within tribal structures and traditions. Religious concepts and practices have been shared over wide areas in the history of Africa and certain religious institutions, such as ancestor veneration, have a near-universal currency. Particularist or holistic studies inevitably present a false picture although they are a necessary stage in our understanding of African religion and provide the primary sources of information. Such studies have been made by social anthropologists, early travellers and explorers, and scientifically minded missionaries. Participant observation, as a method, is required by the oral and ritual nature of the material. Subsequent comparative studies by scholars of religion have been based on this ethnographic material, particularly on recorded prayer-literature. The recent development of oral history has carried the study of African religions considerably further, providing, as it does, hard evidence for the interaction of peoples and the spread of ideas. Finally, modern African poets, novelists, playwrights and political philosophers have added their interpretations to the growing literature on African religion.

Students of African religion were at first sceptical about the possibility of historical studies. Today there is no doubt that they are both possible and worthwhile. Religion permeated every aspect of life in traditional African societies and its history is inseparable from that of their social and political institutions. Over much of the continent, particularly eastern, central and southern Africa, populations have been small and scattered, and poverty of resources has imposed a subsistence economy in the shape of hunting-gathering, shifting cultivation and pastoralism. Such societies did not elaborate rich material cultures, but discovered parables for the spiritual realities of existence in the phenomena of an all-embracing nature. The theologies of such religions, though often subtle, were not elaborate. In the lake regions and forest fringes where soils are richer and rainfall more plentiful, settlement has been more dense and culture technologically more advanced. In such societies theology has been patterned more on the interplay of personalities, divinities and deified human beings,. while religious practice has centred on holy places, graves, shrines, temples and mausoleums. All over the continent territorial and royal cults are found which have played an important role in politico-religious history.

In the colonial era (late nineteenth century to mid-twentieth century) ritual leaders were mostly secularized, and immigrant religions, such as Islam and Christianity, acted as catalysts in an enlargement of social and theological scales. They also added to the doctrinal repertory of African traditional religion and stimulated reinterpretation, particularly with regard to belief in a supreme being or ‘High God’. Certain indigenous belief-systems crossed the Atlantic as a result of the slave trade and survive in recognizable form in Cuba, Brazil and the Caribbean [3]. Such are the well-known vodun snake cult from Benin (see figure 13.1), which has become the Voodoo of Haiti and Jamaica, and the religious traditions from Nigeria, Zaire, Angola and Mozambique which survive as the Candomblé brotherhoods in Brazil, the Umbanda and Macumba spirit cults and the syncretic Batuque traditions.

Within Africa itself, ethnic religious values and traditions have lent a special colour to Islam and Christianity in their orthodox or mission-related forms. They have also taken new forms of their own in the so-called Independent church movements, some of which are not so much neo-Christian or neo-Judaic as neo-traditional, a good example being Elijah Masinde’s Religion of the Ancestors (Dini ya Misambwa) in Kenya. Finally, contemporary Africa is witnessing the appearance of numerous communities of affliction, practising spirit mediumship therapy and also witch eradication movements.

Racial and religious prejudice often bedevilled early accounts of African religions, and it was felt that peoples who were technologically inferior were incapable of ‘higher’ religious feelings and behaviour. Symbolism and mythology were held in contempt by Westerners, who considered scientific facts to be the only realities. Naïve evolutionism was replaced by misguided missionary progressionism and the effort to find vestiges of a ‘primitive revelation’. It was social anthropology that began to appreciate African religions on their own terms, but even then Eurocentric criteria were responsible for concepts such as the ‘withdrawn’ or ‘lazy’ God (deus otiosus), the so-called ‘High God’ and for dualistic or polytheistic interpretations. With regard to comparative analysis, Evans-Pritchard advocated the ‘limited comparative method’ [10] (the study of dissimilarities among contiguous and historically related peoples) while Mary Douglas has proposed categorization on the basis of ‘definable social experience’ [8: IX]. Theologians, such as J. S. Mbiti [20] and E. B. Idowu [16], believe in the essential comparability of all ethnic religions, a ‘super-religion’ which purports to belong to all Africans, while historians, such as B. A. Ogot [24], I. N. Kimambo, T. O. Ranger [26] and R. Gray [14], advocate a more factual, but necessarily more restricted, analysis. Finally, African writers such as Chinua Achebe [1], Ngugi wa Thiongo [23] and Wole Soyinka [31] have chronicled the destruction of the old organic universe; used African religion as an allegory for modern sociopolitical processes; replaced it with an alien, Marxist ideology; or sought to secularize it in modern, tragic theatre.

The Teachings of African Religions

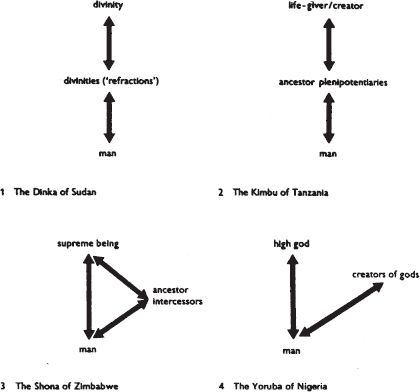

Africa’s approach to the numinous is both personal and ‘transpersonal’. In many instances ‘spirit’ is a category which includes inanimate medicines and fetishes as well as personal beings. Sometimes the concept is unified and the different levels of spirit are seen as ‘refractions’ of an ultimately powerful being, symbolically associated with the sky. This is the case for the northern Nilotes of Sudan, the Nuer [11] and Dinka [19]. In other instances a supreme being is more clearly and exclusively personalized as a creator and/or life-giver, again employing sky-symbolism: sun, rainbow or lightning, for example (see figure 13.2). The supreme being has also been associated with mountains and high hills, Mts Kenya and Kilimanjaro (the latter in Tanzania) being the most celebrated examples, and it is possible that hill-symbolism represents an older stratum of belief than sky-symbolism (see figure 13.3).

Generally speaking, African experience of nature is classified as being either life-fulfilling or life-diminishing; and there is a third, enigmatic category of natural phenomena which seem to share human life or characteristics [7: 9–26; 9]. Thus classified, nature reveals the existence of spiritual realities, beings and powers, as well as means of human communication with the numinous. Very often nature spirits are thought to control the wild animals, as well as the trees and plants that grow in the wilderness, or are associated with lakes, streams or rock-formations. A special place is reserved for the Earth and its (usually female) personalization in African cosmology. Occasionally, Sky – Earth opposition results in a clearly bisexual representation of the supreme being. The ultimate source of evil and disorder in the world is rarely personalized as a spirit, but more commonly traced to the witch, a human being who possesses preternatural powers to harm others secretly and malevolently.

Although there are well-documented instances of totemic spirits who are invoked as the guardians of clans and lineages, the patrons of society are usually the spirits of the dead, the ancestors. The spiritual world of the ancestors is patterned after life on earth. The recently dead and the unremembered collectivity of the remotely deceased are invoked by, and on behalf of, the family community. The territorial spirits who are the ancestors of chiefs or who are eminent personalities of the past are invoked on behalf of larger social groupings. Ancestors are thought to be mediators in one sense or another. They are perhaps seldom conceived of as intercessors, like the Christian saints. More often they are plenipotentiaries of the supreme being, mediating his providence and receiving worship in his name. Occasionally they are seen as mankind’s companions in the approach to the supreme being, guarantors of authentic worship [5; 18]. Much of traditional morality is concerned with pleasing the ancestors and living in harmony with them, since they are the most important members of the total community.

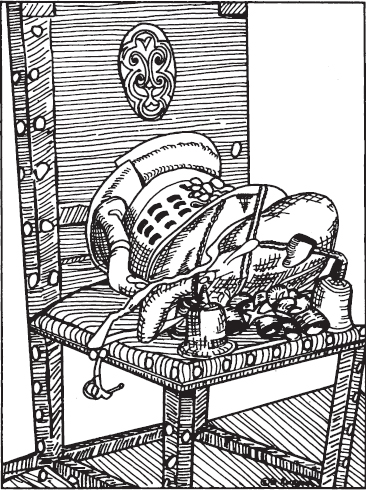

Leadership in traditional Africa was basically ritual leadership, whether of divine kings, or of prophet-arbitrators or spirit-mediums. In the shifting political situation of the pastoralists the leaders were members of prophet-clans which were credited with exceptional spiritual power. Among more settled peoples, the rulers were kings whose own life and well-being was linked cosmo-biologically with that of the universe. Royal cults like that of the ‘High God’ Mwari in Zimbabwe, or the divinity M’Bona in the Shire and Zambezi valleys (Malawi and Mozambique), were often manipulated by rulers [28]. In certain cases, the ruler was himself possessed by, or descended from, a divinity. This was the case of the king (or Reth) of the Shilluk in Sudan who was believed to be possessed by the deified spirit of the first king, Nyikang. It was also true of the Yoruba kings of Nigeria who were said to be descended from the god Odudua, the creator of the Earth, and of the king (Kabaka) of Buganda (Uganda) who was said to be descended from the deified first king, Kintu. Other kings like the king of Ashanti (Ghana) or the king of Ankole (Uganda) possessed the soul or spirit of their people in an important item of their regalia, the ‘Golden Stool’ or the royal drum (figure 13.4).

Figure 13.4 The Golden Stool of the Ashanti, Ghana

It is particularly in the highly developed, monarchical societies that the greatest theological pluralism is encountered. When Christian missionaries appeared on the scene, it was sometimes difficult for them to select a supreme divinity with which they could identify the Christian God. In Buganda, for example, there were three candidates – the god of the sky, the creator god and the first god-king – while in the Yoruba religion the supreme being was king of the gods, but he was the creator neither of the Earth nor of mankind. Such pluralism was basically unsystematic and the question of which divinity was supreme was often unimportant to those concerned. The experience of the numinous consisted in the dialectical interplay between the various spiritual beings. This was expressed mythologically and acted out in various ritual forms. Thus the tensions of human society were reproduced at the spiritual level.

In the precarious existence led by members of traditional African society, life and the transmission of life were important values. Death presented a paradox, since it was both a diminution of life and the gateway to a more powerful participation in life as an ancestor. Generally, one could only qualify for ancestorship by becoming oneself a life-giver, and the afterlife was bound up with a person’s remembrance by the living. Humans could become ancestors, and in certain cases ancestors could become humans again. Peoples like the Ashanti of Ghana have a very clear concept of reincarnation. For them a person is reincarnated again and again until his life-work is complete and he is qualified to enter the world of the ancestors [27: 39–41]. Literal reincarnation is rarer than forms of nominal reincarnation whereby the living benefit by a special protection from their ancestor namesakes. Many people, like the Shona of Zimbabwe, believe that ancestral spirits can possess the living.

African Religion Practices

Foremost among the religious practices of traditional Africa is sacrifice. Among pastoralists it tends to have a markedly piacular or expiatory character and to be offered wholly or mainly to the supreme being. It is, typically, cow-sacrifice and is a feature of the cattle-culture complex. Sacrifice in other groups, however, is far from being reserved to the supreme being alone. It is modelled on human gift-exchange and on customs connected with the sharing of food and drink. First-fruits sacrifices are very common, from the first portions of meat set aside by the hunter when he butchers his quarry, or the first portions of harvested grain, to the first mouthfuls of cooked food or the first mouthfuls of beer. Formal sacrifice at graves and shrines is usually a gift-oblation and is mostly a foodstuff or a libation. However, non-edible goods are also offered, and sometimes living animals, cows, goats or chickens are dedicated without immolation. When sacrifice is made to ancestors it is often likened to the feeding of, and caring for, old people, but it clearly goes beyond purely human ideas of eating and drinking. Ancestors are credited with exceptional knowledge and power, and sacrifice to them is an acknowledgement of their powerful role in human society. Misfortunes are very frequently attributed to a failure to offer sacrifice in due form or due time.

A very great proportion of African religious ritual is ancestral or funerary. This is especially true of territorial cults. The chief is often in some sense a ‘living ancestor’, ruling on behalf of his forebears and ensuring that a regular ancestral cult takes place. The ruler of chiefdom societies in western Tanzania were responsible for periodic offerings at their ancestor’ graves. The rulers of the East African lake kingdoms also regulated the ritual that took place in the tomb-houses of their predecessors and at the shrines where their jaw-bones and umbilical cords were preserved. The Divine King (Oba) of Benin in Nigeria is still obliged to venerate the funerary altars of his ancestor, while in the kingdom of Ashanti the ritually blackened stools of deceased local chiefs are assembled before the king and his Golden Stool, in an important rite of narional solidarity. In Ashanti also the embalmed bodies of former kings are preserved in a special mausoleum and continually repaired with gold-dust.

Mention has already been made of royal, ritual objects such as the Golden Stool of Ashanti, believed to have been conjured from heaven by the priest Anokye, and of royal drums like Byagendanwa of Ankole (Uganda). Such objects are often personified. The Golden Stool, for example, has its own stool, umbrella and attendants, and the Ankole drum has its own wives, servants and household. The ghost-horn blown during the territorial rituals of the Kimbu in western Tanzania is also symbolically identified with the country itself.

In traditional Africa practically every element of life had a religious aspect, and this was the case especially with the rites of passage. Religious invocations and offerings played a part in birth-rites and naming ceremonies, in puberty rituals and other forms of initiation, as well as in marriage ceremonial and in funerals, mourning and inheritance ceremonies. There were numerous professional associations with their own religious rituals. In the more pluralistic societies, where ego-centred networks were as strong as, or stronger than, group loyalties, there were numerous particular cults of spirits or divinities with their own ceremonial repertory of song and dance, and their own traditions of ethical behaviour.

African notions of moral evil include the factual breaking of taboos and the ordinary laws of life, as well as the more grave antisocial actions. The first may be regarded fairly lightly, with only the culprit himself to blame. In the second case, it has to be remembered that traditional society in Africa included the dead as well as the living. An offence against society was, therefore, also an offence against the guardians of society. Redressive and reconciliatory rituals consequently often contained prayer for salvation from sin and its social effects. Although sickness, suffering and misfortune were thought to reveal such offences, a clear distinction was drawn between the state of sin and its effects. Redressive rituals were typically communal, since anti-social behaviour incurred collective guilt and punishment [34]. These rites often involved public confession of faults and symbolic purification. Sometimes they included a communal gesture of renouncing the evil that had brought the misfortune.

Liminal rituals are very common in Africa. These celebrate –and, indeed, try to re-create – the liminal or marginal phase in rites of passage [33: 94–203]. It is an experience of temporary loss of status and social distinctions in which the deep springs of human interrelatedness are rediscovered. In the past, such rituals were performed by secret or semi-secret dance societies or mask societies. Often they acted out traditional cosmological myths or impersonated ancestors and historical personalities. Such were the Nyau societies of Central Malawi and the Egungun society of the Yoruba (Nigeria).

Whether it took a magical or a religious form, divination was always an important stage in the celebration of rituals in Africa. It was the divination process that decided which ritual was appropriate, and thus many religious ceremonies began with divination. If divination itself was a religious ritual it could take the form of spirit-mediumship. In some cases there was a god or divinity of divination who was thought to be the spokesman of the spirit world and who could identify which spirits or ancestors should be approached on a given occasion. Ifa, in the Yoruba pantheon, was such a god of divination.

Popular Manifestations of African Religion

At the popular level the African believer is often more engrossed in the identification of human sources of evil, and in counteracting them, than in the acknowledgement and worship of superior forces of good. The African, it has been said, is ‘naked in front of evil’ [17: 32]. Principally, this means that witch-finding is an important activity, and it involves recourse to the diviner and medicine man. The client approaches the diviner with certain presuppositions and suspicions, and these are rendered explicit in the divination process. The latter affords social approval for a retaliatory course of action against his enemies, and the medicine man provides protective rituals and medicines, as well as retaliatory ones.

The application of magic to areas of religious belief and practice is as rife in Africa as it is in the popular forms taken by religions elsewhere. There are societies, for example, in which it is believed that nature spirits and ancestors ca be manipulated through magical processes. The Ganda (Uganda) believe that ancestral spirits can be conjured into medicine horns and then ‘sent’ to harm an enemy or rival. There is also the belief that a troublesome spirit can be disposed of by conjuring it into a pot which is then totally burnt and destroyed. There is also the possibility that prayer and sacrifice may take on the character of a magical technique with infallible results, if it is correctly performed.

Spirit-mediumship occurs sometimes as a popular form of prayer. It is obviously satisfactory for the worshipper to feel that he is in direct contact with the spirit he addresses and that he can obtain an immediate answer to prayer, even though the message may be somewhat enigmatic. Spirit-mediums may be possessed by nature spirits who are objects of propitiation or by ancestors and hero divinities. In some cases the medium is mentally dissociated and speaks in trance; at other times, he or she simply speaks unfalteringly from the heart, believing that what is said in perfect truth and sincerity is the message of the spirit. This is the case with the Kubandwa mediumship of Rwanda and of the Lubaale spirit-mediumship (personally observed at Kampala, 31 July 1975) in Uganda. Worshippers seek information and guidance from the spirits in this way, and they also give gifts and offer praise to them.

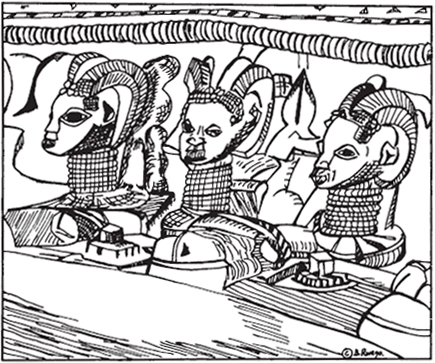

Popular worship takes place in the family context, chiefly through ancestral or totemic rituals. Graves and ancestor shrines or figures play an important part in this worship (figure 13.5). The wearing of protective. charms and emblems is also often thought to be a means through which ancestors exercise their guardianship, and territorial rites of passage, the arrival and departure of travellers, house-moving or the opening up of new cultivation are also occasions for invoking the ancestors and possibly other spirits. Birth-rites, weddings and funerals are fundamentally family celebrations, and in many areas puberty initiation has become a family, rather than a community, affair as a result of the breakdown of traditional social structure. Reconciliation ceremonies take place at neighbourhood level when disputes have to be settled, and these may have a religious, even a sacrificial, character. Although on formal community occasions prayer takes the form of a lengthy praise-poem, or of litanic song, in the ordinary household the typical prayer formula is a short and familiar petition, directly stating the needs of an individual or family. Religious values enter into much of the oral literature of African peoples. Not only are there cosmological and moral themes in myth and etiological folk-tales, but religious ideas underlie proverbs and other didactic forms. Spontaneous oaths and blessings also take a religious form.

Modern Developments in African Religions

It has been estimated that between 30 and 40 per cent of the population of contemporary Africa still practise traditional African religion [2]. If Christians and Muslims who also resort occasionally to traditional practices are included, then the percentage might reach 70 per cent. It remains true, nevertheless, that African religion in its visible form, that is, as structured through pre-colonial tribal institutions, has been severely weakened. As far as ritual is concerned, the trend has been away from communitarian forms and towards individual and familial ones. With regard to concepts, beliefs and values, traditional religion is more tenacious than might be thought. Old ideas survive in new forms. Religion in Africa has always been highly absorbent and prone to syncretism, if not to reinterpretation. The playwright Wole Soyinka has described African religious symbolism as ‘protean’ [31: 122]. Certainly African religion has a remarkable resilience and a surprising capacity to survive in a submerged form.

Islam and Christianity have undoubtedly helped to bring about a monotheistic reinterpretation of traditional theology in some clear instances. Monica Wilson has shown how Kyala, the hero-divinity of the Nyakyusa (Tanzania) developed, under missionary influence, into the Christian God [35: 187ff], while Soyinka has argued that Idowu’s concept of ‘diffused monotheism’, as applied to the Yoruba pantheon (Nigeria) is a Eurocentric reinterpretation [31: 108]. It is generally agreed that Christian eschatology has made a strong impact on traditional religious thought in Africa, and the idea of a bodily resurrection and future bodily existence is certainly attractive to people for whom bodily life and physical generation are important values. It may be tat the conceptual formulations of Christian theology have unwittingly encouraged a literal and materialistic understanding of heaven and hell among Africans [21].

Accelerated organizational change has encouraged the growth of new forms for African traditional religion. One of these is the witch-eradication movement, which has been a recurring phenomenon in Central Africa and southern Tanzania. This is, in a sense, a millenarian phenomenon in which a group of ‘experts’ who are possessed of a new and effective technique claim to be able to cleanse a whole community or countryside of witches and sorcerers. Travelling from place to place, they organize collective rites of purification and reconciliation in which people renounce their witchcraft and their evil powers are neutralized. A new golden age is proclaimed in which people will be free from the fear of witchcraft and sorcery. However, disillusionment usually follows, and there may eventually be further visits from the eradicators. Tomo Nyirenda’s Mwana Lesa movement and Alice Lenshina’s Lumpa Church both in Zambia) are perhaps the most famous of modern, millenarist eradication movements, but there have been numerous others ([25: 45-75]; and see chapter 14 below).

Some so-called ‘Independent churches’ are also traditionalist revivals rather than splinter groups from established mission churches. Other neo-traditional ‘churches’ are racially or ethnically conscious movements which attempt to purge foreign elements, while still other modern religious movements are frankly syncretist. Even an Independent church like the Maria Legio Church of Kenya, which is ostensibly a schism from the Roman Catholic Church, inspired by the lay association known as the Legion of Mary, is in fact better understood in terms of the juogi spirit beliefs of the Luo tribe. But even those independent movements like the Religion of the Ancestors (Dini-ya Misambwa, also in Kenya) or the ethnically conscious Kikuyu churches which nurtured the Mau Mau protest that precipitated Kenyan independence, were reinterpretations of traditional religion under the influence of Christianity.

Of equal interest is the way in which traditional values and institutions have shaped or affected religious movements which are demonstrably Christian and even orthodox Christianity itself [12]. Many Christian Independent churches have an organization which derives from traditional models of ritual or prophetic leadership. Dreams, mythology and spirit-mediumship may also play an important pan in the life of these churches. In the mission-related churches, now under African leadership, the exercise of authority, as well as liturgical and musical adaptations, owes much to non-Christian traditions. Moreover, since Christian missionaries refused to accept African traditional religion as a coherent philosophy (albeit couched in symbolic and mythological language), neophytes have not been required to renounce their previous religion effectively. The result, as Robin Horton indicates, is a process of ‘adhesion’, rather than ‘conversion’, resulting in a crypto-traditionalism [15].

An interest which unites traditional religion, independent church movements, mission-related Christianity and the various forms of Islam is undoubtedly spirit-mediumship and spirit-healing. Among Christians the Pentecostal movement has exerted a strong influence, but the exorcism of evil spirits is also gaining popularity and even official approval. In the case of exorcism, the practice owes more to traditional ideas about morally neutral, but none the less malevolent, personifications of misfortune, than to Christian demonology. The Islamic jinn are also comparable to these traditional spirits. Many independent churches are basically Pentecostal, and it has been conjectured that the Pentecostalism which is now influencing Africa derives in part from spirit-possession cults which were carried to the New World by African slaves in the first place [4]. Certainly the neo-African and syncretic cults in Brazil and elsewhere tend to emphasize spirit-mediumship [3].

Finally, it cannot be denied that politicians and statesmen in independent African countries have exploited traditional beliefs as well as the politico-religious character of traditional leadership in order to consolidate their power. This opportunism has been denounced by – among others – Wole Soyinka as a trivialization of the essential, ‘with catch-all diversionary slogans such as “authenticité”’ [31: 109]. In spite of such false prophets of retrieval, traditional religious values continue to exert their influence both within and outside the religious organizations of contemporary black Africa and to presage the transformation even of Islam and Christianity.

More Recent Developments

African religions have retained their importance during the last quarter of the twentieth century, especially through their increased influence on the mainstream churches and faiths and on new religious movements in the continent. Traditional religious rituals are still performed in many contexts by educated and even ‘Westernized’ Africans. Often these contexts relate to marriage, childbirth, burial, inheritance or royal succession. Three outstanding examples which took place in 1986 can be cited here as examples. In April of that year, a young teenager was whisked from his college in England to the throne of Swaziland in southern Africa. The young monarch, Mswati III, underwent elaborate secret rituals in which he was symbolically sacrificed for the nation. In August a Tanzanian bank manager and Member of Parliament went through a complicated series of rituals at his father’s graveside. During the ceremonies he was introduced to his ancestors as the new senior chief of the Kimbu tribe and was empowered to communicate with them. In December of the same year a five-month legal tussle began in Kenya between relatives by marriage, belonging to different tribes, over the burial of a prominent Nairobi lawyer. The traditionalists won. Such examples abound, and they demonstrate the tenacity of traditional religion.

In July 1993 the traditional kingdoms were restored in Uganda, chief among them being the Kingdom of Buganda. Twenty-seven years after his father fled the country, Ronald Muwenda Mutebi II became the thirty-sixth Kabaka of Buganda. Lengthy traditional ceremonies took place in secrecy on the royal hill of Budo, during which the new king struck the kyebabon, or royal drum. This was followed by a Christian coronation ceremony. The restoration of these monarchies is another example of a public return to traditional ritual and of a cultural recovery affecting many pans of Africa.

There is also abundant evidence of continuing witchcraft practices and beliefs. Witchcraft cleansing is increasingly popular, especially in Central Africa, and it often takes on the character of a new religious movement. It tends to be directed against anti-social elements, as well as against mainstream Christianity, especially Catholicism. Puritanical Protestant attitudes help the adepts to recognize Catholic devotional objects as instruments of witchcraft. Witchcraft is generally believed to be an ever-present reality and it continues to command the attention of traditional healers and divines in both rural and urban areas.

The massive influx of migrants to the towns and cities of Africa over the past decade has increased the tensions which give rise to accusations of witchcraft. It has also probably encouraged traditional healers to adopt a more modern appearance. Frequently, they stress the ‘scientific’ character of their practice, and like to claim proficiency in palmistry, astrology or herbal medicine. They also adopt the titles of ‘Doctor’ ‘Professor’ or ‘Sheikh’. However, their techniques still include traditional religious rituals, the interpretation of dreams and the propitiation of spirits.

The mainstream Christian churches have taken a more serious interest in traditional African religion. Greater pastoral attention to traditional religion has been called for, and some attempts at formal dialogue with its practitioners have even taken place. Most of the interest, however, centres on the concept of inculturation, the idea that the Christian Gospel should engage in dialogue with traditional religion from within and that Christianity should be re-expressed in African cultural and religious forms. Two well-known instances in which the Catholic church has formally come to terms with African religious ideas are the Zaire Mass and the Zimbabwe Second Burial Rite.

At the same time, the Independent churches, which have always been vehicles for the beliefs and values of traditional religion, have tended to become more sophisticated. This is partly due to urbanization, and it is noticeable that these movements flourish in African towns and cities. In some cases, as in Kenya, they have become organized into associations of churches. Although they still cater mainly for the poorer classes, there is a considerable fluidity of membership between them and the mainstream churches. This suggests that they have a wider, if not a growing, appeal, and that they cater for certain religious needs more successfully than mainstream Christianity.

Much of this new sophistication derives from the Pentecostalist explosion of the 1980s. On the one hand, a fundamentalist form of evangelical Christianity, which reflects the response of the southern United States to modern social and geopolitical trends, has begun to affect Africa. On the other hand, African Independent churches have been finding among the proponents of this form of Christianity sponsors for their own foundations. The popular form of this fundamentalism, promoted by crusades and Bible schools, ascribes individual and social evils to demons. To this is added the faith-gospel promise of health and wealth to all who believe and who support evangelism.

Such teachings have found an immediate echo in the African religious mentality. One widespread consequence has been the demonization of traditional alien spirits, and the proliferation of Christian exorcists – even in the mainstream churches – one of the most celebrated of whom is Emmanuel Milingo, former Catholic Archbishop of Lusaka, called to Rome in 1982. Another consequence has been to strengthen the preoccupation with health and healing, and to encourage a form of faith which virtually transforms new religious movements into African ‘cargo cults’.

So far from encouraging Independent churches to become protest movements, the millenarianism and dispensationalism of the new trends from America have made them submissive and docile to brutal totalitarian regimes, and have helped to entrench the rule of corrupt and inhuman dictators. There has been little evidence, so far, of a traditionalist backlash against this new form of American and/or Western religious influence.

The most fruitful prospers for the visible survival of traditional religion in Africa probably lie in the tolerance now being shown by mainstream Christianity and the latter’s desire for genuine dialogue and coexistence.

Bibliography

1 ACHEBE, C. Things Fall Apart, London, Heinemann, 1958; New York, McDowell, Obolensky, 1959

2 ARINZE, F., and TSHIBANGU, T., ‘Rapport du groupe des religions traditionelles africaines’, Bulletin: Secretariatus pro non-Christianis (Vatican City), vol. 14, nos 2–3, 1979, pp. 187–90

3 BASTIDE, R., The African Religions of Brazil (tr. H. Sebba), Baltimore/London, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978; first publ. As Les Religions africaines au Brésil, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1960

4 BECKMANN, D. M., Eden Revival: Spiritual Churches in Ghana, St Louis, Concordia, 1975

5 BERNARDI, B., The Mugwe, A Failing Prophet: A Study of a Religious and Public Dignitary of the Meru of Kenya, London/New York, Oxford University Press/International African Institute, 1959

6 DE HEUSCH, L., Sacrifice in Africa: A Structuralist Approach, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1985

7 DOUGLAS, M., Implicit Meanings: Essays in Anthropology, London/Boston, Routledge, 1975

8 DOUGLAS, M., Natural Symbols: Explorations in Cosmology, London, Barrie & Rockliff/New York, Pantheon, 1970; 2nd edn London, Barrie & Jenkins/New York, Vintage, 1973

9 DOUGLAS, M., Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, London, Routledge/New York, Praeger, 1966

10 EVANS-PRITCHARD, SIR EDWARD E., The Comparative Method in Social Anthropology, London, Athlone Press, 1963 (L. T. Hobhouse Memorial Lecture no. 33)

11 EVANS-PRITCHARD, SIR EDWARD E., Nuer Religion, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1962; 1st publ. 1956; new edn London, Oxford University Press, 1970

12 FASHOLÉ-LUKE, E. W., et al. (eds), Christianity in Independent Africa, London, R. Collings/Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1978

13 GIFFORD, P., Christianity and Politics in Doe’s Liberia, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1993

14 GRAY, R., ‘Christianity and Religious Change in Africa’, in The Church in a Changing Society, Stockholm, Almquist & Wiksell (distr.), 1978 (CIHEC Conference, Uppsala, 1977), pp. 345–52

15 HORTON, R., ‘On the Reality of Conversion in Africa’, Africa, vol. 7, no. 2, 1975, pp. 132–64

16 IDOWU, E. B., African Traditional Religion: A Definition, London, SCM/Maryknoll, NY, Orbis, 1973

17 ILIFFE, J., A Modern History of Tanganyika, Cambridge/New York, Cambridge University Press, 1979

18 KENYATTA, J., Facing Mount Kenya: The Tribal Life of the Gikuyu, London, Secker & Warburg, 1938, repr. 1953; school edn Nairobi, Heinemann, 1971

19 LIENHARDT, G., Divinity and Experience: The Religion of the Dinka, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1961

20 MBITI, J. S., African Religion and Philosophy, London/Ibadan, Heinemann; New York, Praeger, 1969

21 MBITI, J. S., New Testament Eschataology in an African Background, London, Oxford University Press, 1971

22 MURDOCK, G. P., Africa: Its Peoples and their Culture History, New York, McGraw-Hill, 1959

23 NGUGI WA THIONGO, Petals of Blood, London, Heinemann, 1977

24 OGOT, B. A., History of the Southern Luo, vol. 1, Migration and Settlement, 1500–1900, Nairobi, East African Publishing House, 1967

25 RANGER, T. O., ‘The Mwana Lesa Movement of 1925’, in T. O. Ranger and I. N. Kimambo (eds), The Historical Study of African Religion, London, Heinemann, 1972; Berkeley, University of California Press, 1972, repr. 1976, pp. 45–75

26 RANGER, T. O., and KIMAMBO, I. N., The Historical Study of African Religion, London, Heinemann, 1972; Berkeley, University of California Press, 1972, repr. 1976

27 SARPONG, P. K., Ghana in Retrospect: Some Aspects of Ghanaian Culture, Tema, Ghana Publishing Corporation, 1974

28 SCHOFFELEERS, M., ‘The Interaction of the M’Bona Cult and Christianity, 1859–1963’, in T. O. Ranger and J. Weller (eds), Themes in the Christian History of Central Africa, London, Heinemann/Berkeley, University of California Press, 1975, pp. 14–29

29 SHORTER, A., The Church in the African City, London, Geoffrey Chapman, 1991

30 SHORTER, A., Jesus and the Witchdoctor: An Approach to Healing and Wholeness, London, Geoffrey Chapman, 1985

31 SOYINKA, W., Myth, Literature and the African World, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1978; 1st edn 1976

32 TER HAAR, G., Spirit of Africa: The Healing Ministry of Archbishop Milingo of Zambia, London, Hurst, 1992

33 TURNER, V. W., The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure, London, Routledge/Chicago, Aldine, 1969

34 TURNER, V. W., Schism and Continuity in an African Society: A Study of Ndembu Village Life, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1957

35 WILSON, M., Communal Rituals of the Nyakyusa, London/New York, Oxford University Press/International African Institute, 1959