江雪

千山鳥飛絕

萬徑人蹤滅

孤舟簑笠翁

獨釣寒江雪

In his essay “The Poem behind the Poem,” the translator/anthologist Tony Barnstone offers an extended discussion of his experience translating the poem reproduced above, by the Tang poet Liu Zongyuan (柳宗元, b. 773–d. 819). Before offering his translation, Barnstone leads his readers in what appears to be a guided meditation: “Let us take a minute to read it aloud, slowly. Empty our minds. Visualize each word.” His translation follows:

A thousand mountains. Flying birds vanish.

Ten thousand paths. Human traces erased

One boat, bamboo hat, bark cape—an old man

Alone with his hook. Cold river. Snow.1

Barnstone then comments: “Snow is the white page on which the old man is marked, through which an ink river flows. Snow is the mind of the reader, on which these pristine signs are registered, only to be covered with more snow and erased…. I like to imagine each character in ‘River Snow’ sketched on the page: a brushstroke against the emptiness of a Chinese painting—like the figure of the old man himself surrounded by all that snow.”2

Barnstone asserts that each line of the translation “should drop into a meditative silence, should be a new line of vision, a revelation. The poem must be empty, pure perception; the words of the poem should be like flowers, one by one opening, then silently falling.”3 Michelle Yeh, a well-known scholar of modern Chinese poetry, might notice, as I would, that Barnstone’s poetic diction offers a particular lens through which we are invited to view the “poem behind the poem.” As Yeh has pointed out, the poem can as easily be read as an expression of possible class tensions (an old man unbearably cold in a bitter landscape).4 Furthermore, we are not to look at how the poetic form may conform to state-sponsored aesthetics, or how, as Lucas Klien has argued, the poem’s prosodic effects might undermine its outward appearance of quietude.5 Instead, Barn-stone chooses to emphasize a loosely philosophical language that is hard to pin down: What does it mean that a poem must be “empty”? How are we to imagine this so-called “pure perception”?

According to Michelle Yeh, Barnstone likes to imagine things. In her short essay, “The Chinese Poem: The Visible and the Invisible in Chinese Poetry,” she argues that, “implicit in the Anglo-American perception of the Chinese poem is a particular kind of correlation between stylistics and epistemology (namely Buddho-Daoist).” And it is this correlation that she finds questionable.6 For Yeh, Barnstone not only imagines the snowy scene, he also imagines that classical Chinese poetry is the embodiment of a loosely Buddho-Daoist worldview and that the translator’s task is to channel this worldview, to transfer its epistemological and ontological orientation to the reader, not through a discursive “explanation” but through English verse which enacts it. Yeh finds this reductive reading of classical Chinese poetry problematic because it limits other possible meanings and reading frames, and while I share Yeh’s point of view, I think that one cannot dismiss these “Buddho-Daoist” claims. Instead, we need to focus on these claims, as a specific domain of heterocultural poetics conditioned by a history of transpacific intertextual travels. Reductive—yes—but important nonetheless.7

Of course, Barnstone is only one of a host of American translators, poets, and critics who naturally assume a particular correlation between East Asian philosophy and poetry—what in shorthand I am dubbing a “poetics of emptiness.” Clearly, the generations of American poets who have turned to Chinese poetry have also turned to this imagined geography—a “transpacific imaginary,” or nexus, of intertextual engagements with classical East Asian philosophical and poetic discourses.

By using the term “imaginary,” I do not want to imply a dichotomy between imagination and reality. I do not want to imply that these poets have simply “imagined,” that is, made up, or projected, an “Asian fantasy” into their poetic practices (although this may be also applicable at times). Instead, I want to present their ability to bring into view what are, prior to their imaging, merely potential heterocultural configurations. In other words, I want to privilege and yet complicate the positive denotation of “imagination” as the ability to deal with reality through “an innovative use of resources”—as in, she handled the problems with great imagination. Yet I will not be using the term “imaginary” as a romantic expression of the creative individual either. Instead, I prefer to follow Rob Wilson, who defines an “imaginary” as a “situated and contested social fantasy.” As he writes, “In our era of transnational and postcolonial conjunction [ … ] the very act of imagining (place, nation, region, globe) is constrained by discourse and contorted by geopolitical struggles for power, status, recognition, and control.”8 I embrace this more complicated view of imagination because the generation and proliferation of competing forms of the poetics of emptiness explored in this work cannot escape the geopolitical contexts in which they arise. Therefore, I want not only to chart the catalytic role that concepts of emptiness have come to play in the creation (imagining) of new poetic discourses and aesthetics in twentieth-century American literature, but also to show how these discourses draw upon and contribute to distortions of East Asian poetics and philosophy generated from within historically and politically specific social contexts. While sorting through these situated distortions comprises much of the work performed in the following chapters, I want to foreground how each of the poets examined here transforms both East Asian philosophy and American poetics through their explicit attempts to fuse distinct discourses into new, heterocultural productions. And while this book will show how notions or images of “emptiness” displace multiple other (and often very important) elements of Chinese poetry and poetics in the American poetic consciousness, it will also show how these “transpacific imaginaries” are valuable and worthy of our careful attention.

While the term “transatlantic” has found a prominent place in American and British literary criticism, the term “transpacific” has only recently been introduced as a category or region of interest to contemporary literary critics. One must be careful with such concepts since they can become subsumed within the conceptual networks that undergird existing geopolitical discourses, like those which imagine a space of neoliberal transnational corporate exchange that collapses difference, thus creating a smoothed over region across which cultural and capital exchanges freely and “neutrally” take place. Rob Wilson problematizes the idea of a “Pacific Rim,” or “Asia Pacific,” when he argues that “the commonplace and taken-for-granted assumption of ‘region’ implied by a signifying category like ‘Asia-Pacific’ entails an act of social imagining,” which, he continues, “had to be shaped into coherence and consensus in ways that could call attention to the power politics of such unstable representations.”9 So I would like to cautiously employ the term “transpacific” to demarcate the historically specific cultural and textual pathways across which various philosophical, literary, and aesthetic discourses travel, specifically from China (often by way of Japan) to America.

In this sense, my usage of the term follows that of Yunte Huang, who uses “transpacific” in conjunction with “displacement” to describe “a historical process of textual migration of cultural meanings, meanings that include linguistic traits, poetics, philosophical ideas, myths, stories, and so on.” Such displacement, continues Huang, “is driven in particular by the writers’ desire to appropriate, capture, mimic, parody, or revise the Other’s signifying practices in an effort to describe the Other.”10 As a way of distinguishing his notion of “displacement” from Stephen Greenblatt’s concept of “appropriative mimesis,” which Greenblatt defines as “imitation in the interest of acquisition,” Huang emphasizes that the “appropriative mimesis” of American poets could not avoid making “images of the Other.” This “imaging,” or ethnographic impulse, lies at the heart of what Huang calls “displacement,” insofar as the “ethnographic vision,” or “image,” of the Other displaces “multiple readings of the ‘original’” into “a version that foregrounds the translator’s [or ethnographer’s] own agenda.”11 Following this definition, the various ways in which American poets and critics have imagined classical Chinese poetry as a “poetics of emptiness” can be considered a “displacement” of other readings of the same body of literature and poetics.

I would like to pause for a moment to clarify my preference for the prefix “hetero-” (which I use to emphasize “heterogeneity,” “mixture,” “uneveness,” not “heterosexuality”) over the more commonly used prefixes “cross-,” “inter-,” or “trans-,” to describe the cultural works in this book. Wai-lim Yip (葉維廉, Ye Wei-lien), a prominent transpacific poet and critic who has published more than forty books, conceives of his work as a “cross-cultural poetics,” understood through the somewhat dated ideas of what can be called Whorfian linguistic determinism. Yip draws parallels between the lack of tense conjugation in Chinese and the different concepts of time in the Hopi language, which undergirds the Whorf-Sapir thesis.12 Yip quotes Whorf at some length: “I find it gratuitous to assume that a Hopi who knows only the Hopi language and the cultural ideas of his own society has the same notions, often supposed to be intuitions, of time and space that we have, and that are generally assumed to be universal.”13 Yip agrees, and he further endorses Whorf’s belief that there are no adequate words in Western languages to define Hopi metaphysics: “Whorf has demonstrated excellently that to arrive at a universal basis for discussion and understanding it is dangerous to proceed from only one model; we must begin simultaneously with two or three models, comparing and contrasting them with full respect and attention to indigenous ‘peculiarities’ and cultural ‘anomalies.’ ”14

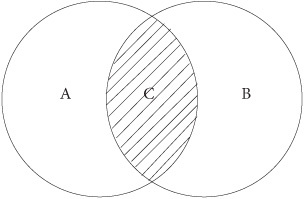

FIGURE p.1. Wai-lim Yip’s cross-cultural interpretation diagram. From Wai-Lim Yip, Diffusion of Distance: Dialogues between Chinese and Western Poetics, 18. © 1993 Regents of the University of California. Published by the University of California Press.

Having affirmed Whorf’s ideas, Yip then offers up a diagram to clarify his own idea of a “cross-cultural poetics” (see Figure P.1). Yip argues that circle A and circle B represent two distinct cultural models, and that the shaded area C, where the two circles overlap, “represents resemblances between the two models” that can serve as “the basis for establishing a fundamental model.”15 To produce such a model, Yip argues, the poetics of culture A must not be subjected to the terms of circle B, or vice versa. In Chapter 4, I explore Yip’s formulation of this discourse on models as an extension of the Daoist concepts of wuwei and ziran, but for now it is sufficient to point out the general conceptual horizons of his cross-cultural poetics. Yip’s term, “cross-cultural,” could equally be replaced by the term “intercultural,” since he envisions cultures as distinct spheres (represented by circles). Like the cognate term, “interpersonal,” which refers to contact between two distinct bodies, “intercultural” does not refer to heterogeneity, but to autonomous spheres that can be compared. The shaded area C in Yip’s diagram does not represent a place of cross-fertilization, or cultural heterogeneity, but simply an area of cultural similarity which comparative literature scholars find and map. Both prefixes, “cross-” and “inter-,” imply purely distinct cultural worlds between which comparisons can be made but does not make room for actual heterocultural admixture.

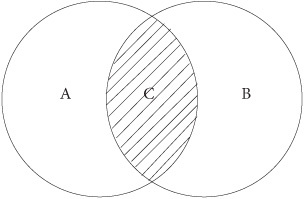

The sinologist Zong-qi Cai praises Yip for his emphasis on “the basis of equality for any truly ‘cross-cultural’ dialogue.” But Cai also questions the adequacy of Yip’s model: “In it [Yip’s diagram] we can find no clues as to from which point of view we should look at the similarities and differences shown. We are left to conceive of three possible points of view: from A, B, or C. If we look at the similarities and differences solely from either A or B, we will be seeing two cultural traditions through the vistas of one, and hence become susceptible to the two polemics. On the other hand, if we focus our attention solely on C, we will be tempted to overemphasize the similarities to the point of essentializing them as ‘universals,’ and consequently neglect the examination of differences.”16 Cai then offers his own model, as shown in Figure P.2. Cai’s diagram has improved upon Yip’s insofar as all of the lines constituting boundaries are represented as porous and dynamic rather than autonomous and static. For Cai, however, the main change between the two is his establishment of a “transcultural perspective” from which he attempts to locate his own work. Cai argues that this perspective “is born of an effort to rise above the limitations and prejudices of any single tradition to a transcultural vantage point, from which one can assess similarities and differences without privileging, overtly or covertly, one tradition over another.”17 While I applaud Cai’s perforation of the boundaries, his attempt to establish such a “transcultural vantage point” reveals a certain non-self-reflexivity toward the cultural conditions of his own thinking. To be fair, Cai offers this transcultural vision as a goal rather than as a description of scholarship directed at such a goal, but the transcultural position, like the cross- and intercultural concepts would fail to acknowledge the already heterocultural nature of the transpacific imaginary. In a sense, the prefixes “inter-,” “cross-,” and “trans-” are circumscribed by the limitations of strictly comparative scholarship and as a result remain unable to address the fact that the cultural productions they name are almost always heterocultural productions themselves.

In short, there is a problem with using the diagrams, as well as these comparative prefixes, as conceptual aids for visualizing heterocultural productions. Diagrams are devices largely developed and deployed in the social sciences to map complex cultural phenomena. As visual aids, they can be helpful but also harmful. What would a diagram presenting the different configurations of a poetics of emptiness as discussed in this book look like? Would the multiple circles drawn circumscribe cultural phenomena associated with individual nation-states, ethnicities, cultures, races, time periods, or some other conceptual grouping? Such circles would be wrong from the start. Take China, for example (but you could just as easily take America, Europe, or Russia). China conceived of as a nation-state, a unified culture, or a “race” is an illusion—or, to be more specific, an ideological formation. These terms are and have been deployed to consolidate power over a heterogeneous population, and drawing a circle around China reinforces this ideology. The visual representation of boundaries, common in mapmaking, and even seen in the Chinese character for nation-state, 國, traffics in the language of siege warfare, and I believe it cannot be relied upon to explore the intricacies of heterocultural literary productions.

FIGURE p.2. Based on material in Zong-qi Cai’s Configurations of Comparative Poetics, 16.

This term, “heterocultural,” avoids the pitfalls of “cross-,” “inter-,” and “trans”-cultural, since it does not posit two pure, autonomous cultures between which transmissions or crossings can occur, nor a transcendent position beyond culture itself, but instead complicates the very conceptual integrity of monolithic concepts of culture altogether. Yet I do not believe that this term can be applied equally to all cultural productions; instead, I want to reserve its use for those texts that are clearly working from within multiple cultural idioms.

Heterocultural texts offer an opportunity to expand literary criticism’s interpretive frames—make them subtler, add new registers, and tune new antennae. If we want to move beyond Greenblatt’s metacritical notion of “appropriative mimesis” to engage the heterocultural theories of language and perception animating such texts, it is my belief that literary critics must formulate interpretive frames as hybrid as the texts being read. This entails a heterocultural criticism that forms itself dialogically with the texts being interpreted. Instead of assuming that a given theoretical frame is sufficient to respond to the heterocultural discourses animating a text being read, the critic acknowledges when additional study is required and pursues these leads. Trying to explicate the term “emptiness” even within its most explicitly “Buddhist” occurrences, as in the work of Gary Snyder, might require a critic to trace the term through at least three distinct Japanese schools of Buddhism (Soto and Rinzai Zen and Kegon) before it further bifurcates into Chinese and Indian schools. Such intertextual travels reveal “emptiness” to be a heterogeneous nexus of potential meanings every bit as contentious as, say, “truth” or “beauty” in Western philosophy and literature (a point I will pursue further in the Introduction). Tracing the term’s use value in Zen poetics offers still more pathways and sinkholes. Of course, we know such semiotic caverns are infinite, just as we know that the need for spelunking is also absolutely necessary.