Danny seemed to be a hopeless case. In spite of a well-to-do home environment in Los Angeles, complete with the support and care of loving, attentive parents, by the age of three he was stealing constantly. Further into childhood he became a compulsive and adept liar. At the tender age of ten, Danny was not just staying out all night, he was buying and selling drugs. He was known by other neighborhood kids as a nasty piece of work, and because it was a middle-class neighborhood they steered well clear of him. And it wasn’t for lack of trying on his parents’ part. As his mother recalled, “No matter what the discipline was, or the consequences of his misbehavior, it was never enough. There was no stopping him. We were really at a complete loss for answers.”1

Danny grew older and stronger, and essentially commandeered his parent’s house. He stole cars and appropriated his mother’s jewelry for drug dealing. He was getting F’s in school. He was a precocious abuser of drugs, graduating from cannabis to speed to cocaine to crystal meth. When he was fifteen he was sentenced to eighteen months in a juvenile detention center. It’s a familiar story, with all the early telltale signs of a life of crime, and likely violence too—perhaps another Jeffrey Landrigan in the making.

Out of sheer desperation his parents entered him in a biofeedback treatment clinic after his release from the detention center. These alternative-medicine clinics assess the physiological profiles of individuals with clinical problems to ascertain whether any physiological imbalance can be corrected. How? By helping them become more aware of their biology and teaching them to change their brain. At that point, neither Danny nor his parents actually had any hope that the treatment would do any good. They felt they were just going through the motions—but they turned out to be wrong.

The first clinical evaluation confirmed excessive slow-wave activity in Danny’s prefrontal cortex—a classic sign of chronic under-arousal. Then came thirty sessions of biofeedback. Danny sat in front of a computer screen with an electrode cap on his head, which measured his brain activity as he played Pac-Man on the computer. Danny controlled Pac-Man, trapped in a maze, and his task was to move around, gobbling up as many pellets as he could. He could only move Pac-Man by maintaining sustained attention—by transforming his frontal slow-wave theta activity into faster-wave alpha and beta activity. If his attention lapsed, Pac-Man stopped. By maintaining his concentration, Danny was able to retrain his under-aroused, immature cortex, which had constantly craved immediate stimulation, into a more mature and aroused brain capable of focusing on a task.

It was hardly a quick fix. For Danny, the biofeedback training lasted for nearly a year. But a metamorphosis took place over the course of his thirty treatment sessions. He was radically transformed, from an inattentive, F-grade teenager on a downward spiral toward prison into a mature, straight-A, career-oriented student who ended up passing his exams with distinction. It was a complete reversal of fortune.

What accounted for the dramatic change? To begin to answer, we have to look back at what was fueling Danny’s antisocial behavior, which started as early as toddlerhood and exploded during adolescence. “I was really bored in school,” Danny would say after his treatment was completed, “but all the crimes were really exciting to me. I liked the action, getting away from the cops. I just thought it was so cool.”2

The thirst for stimulation-seeking is clear. We documented in chapter 4 how children who are chronically under-aroused seek out stimulation to jack their physiological arousal levels back to normal. We know from longitudinal research that schoolchildren with excessive resting slow-wave EEGs are much more likely to become adult criminal offenders.3 That’s exactly what Danny demonstrated in his first clinical evaluation session—excessive delta and theta activity, chronic cortical under-arousal. We also discussed how poor prefrontal functioning predisposes an individual to impulsive homicide. We saw how when the home environment is loving and devoid of deprivation, yet the child is still antisocial, we should expect biology to be the culprit in crime—the social-push hypothesis.

We see in Danny’s case an example of how biology is not destiny. The psychophysiological, brain-based predispositions to crime and violence are not immutable. Importantly, Danny himself—albeit with the aid of electronic biofeedback and social support—instituted his own metamorphosis. It’s more a case of mind over matter. He had agency in his rehabilitation—and that may have been a critical component in his redemption.

Of course there is no easy solution to crime and violence, and Danny is just a case study. Yet what I want to give you in this chapter is a hopeful message. Rather than giving up when faced with biology-based offending, we can use a set of biosocial keys to unlock the cause of crime—and set free those who are trapped by their biology at an early age.

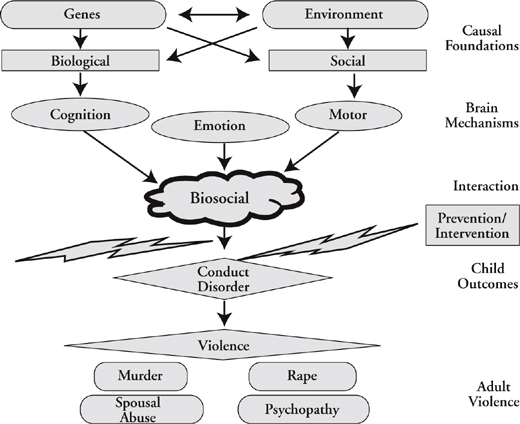

Before embarking on what may work to help kids like Danny, let’s summarize what I have been arguing so far, using a theoretical framework to give a context to treatment efforts. You can see it visually in Figure 9.1.

This biosocial model emphasizes the role of genes and the environment in shaping the factors that predispose someone to childhood aggression and adult violence. A key assumption is that joint assessment of social and biological risk factors will yield innovative new insights into understanding the development of antisocial behavior.

The right-hand side of the figure outlines the main components of the model. Starting at the top, we have both genes and environment as the causal foundations of later violence. Social risk factors, on the right, have been the understandable focus of social scientists for three-quarters of a century. Biological risk factors, on the left, reflect neurocriminology, the new and more challenging field of enquiry.

Genes and environment are the building blocks for the biological and social risk factors in the next lower step in the model. Yet you’ll also see arrows linking genetics with social factors as well as with biological risk factors. Genes can shape social risk factors for violence such as low social class and parental divorce.4 Similarly, social risk factors like environmental stress can impair brain functioning, while living in a risky neighborhood can increase the chance of head injury.

Figure 9.1 Biosocial model of violence

Biological and social risk factors then give rise to brain risk factors that are played out at three levels: cognition (e.g., attention deficits), emotion (e.g., lack of conscience), and motor (e.g., disinhibition) processes. This brain dysregulation can then do one of two things. It can move on to directly give rise to conduct disorder and violence, or it can join forces with social influences to form a biosocial interaction that brings on the teenage thunderstorms of emotion. This biosocial pathway is what I tried to emphasize in the previous chapter, and consequently I place it here as the heart of the model of the anatomy of violence.

Yet there is one piece missing. It is this juncture in our journey—what you see in the dynamic center part of the model—that we will now focus on. The lightning bolts represent striking out the biosocial pathway to adult violence. So what are the biosocial interventions that can block the development of conduct disorder and violence?

One approach to stopping violence—one that we see all too often today—is to wait until the child is already kicking down the doors and becoming unmanageable. Unfortunately, by then it’s often too late to effectively correct course. Why not intervene early in life to prevent future violence?

That’s what David Olds did in a landmark study that won him the Stockholm Prize—criminology’s equivalent to the Nobel Prize. You’ll recall that mothers who smoke during pregnancy have offspring who are three times more likely to become adult violent offenders.5 Birth complications are another risk factor.6 We also discussed how poor nutrition during pregnancy doubles the rate of antisocial personality disorder in adulthood.7 We’ve noted the importance of early maternal care during the critical prenatal and postnatal periods of brain development.8 Alcohol during pregnancy is also associated with later adult crime and violence.9 These are the biosocial influences that David tackled.

His sample consisted of 400 low-social-class pregnant women who were entered into a randomized controlled trial. The intervention group had nine home visits from nurse practitioners during pregnancy, with a further twenty-three follow-up visits in the first two years of the child’s life—a critical time window in child development. The nurses gave advice and counseling to the mothers on reducing smoking and alcohol use, improving their nutrition, and meeting the social, emotional, and physical needs of their infant. The control group received standard levels of prenatal and postnatal care. Follow-ups were made on the offspring for fifteen years.

The results were dramatic. Compared with controls, the children whose mothers had nurse visitations showed a 52.8 percent reduction in arrests and a 63 percent reduction in convictions. They also showed a 56.2 percent reduction in alcohol use and a 40 percent reduction in smoking. Truancy and destruction of property were reduced by 91.3 percent. These effects were even stronger in mothers who were unmarried and particularly impoverished.10

Why was this early intervention so effective? Clues come from other effects of the program. The babies of mothers visited by nurses were less likely to have low birth weight. When the children were age four, the mothers and children were more sensitive and responsive to each other. There was less domestic violence. More of these mothers enrolled their children into preschool programs. The homes became more supportive of early learning. The mothers’ executive functioning also improved, and they had better mental health. These improvements were especially true for mothers who were less intelligent and competent.11 When the children were age twelve, the mothers were less impaired from alcohol and drug use, their partnerships were lasting longer, and they continued to have a greater sense of mastery.12

Providing those mothers most at risk for having wayward offspring with health information, education, and support can reverse later adolescent problems that are the harbingers of adult violence. David Olds was tackling not just the social risk factors we see in Figure 9.1, but also the biomedical health factors that join forces with social risk factors to create antisocial behavior. He was tackling the biosocial part of the equation in Figure 9.1, and that’s why it worked so well.

The cost of the intervention per mother was $11,511 in 2006—but the government saved $12,300 in food stamps, Medicaid, and other financial aid to the families. The government actually spent less on the intervention group than they spent on the control group.13 And that’s not counting the savings brought about by reducing crime, and the incalculable benefits of improving people’s lives.

You’ll remember Beauty and the Beast from Mauritius in chapter 4. Joëlle, who became Miss Mauritius, and Raj, the biker who became a career criminal. They were two of the three-year-old children in the study that my PhD supervisor Peter Venables set up—an environmental enrichment from ages three to five that tells us that while it’s never too early to start to prevent crime, it’s also never too late.

What did our enrichment intervention consist of? It started at age three, had a duration of two years, and consisted of three main elements: nutrition, cognitive stimulation, and physical exercise. The enrichment was conducted in two specially constructed nursery schools. Staff members were brought up to speed on physical health—including nutrition, hygiene, and childhood disorders. They also received training on physical activities, including gymnastics and rhythm activities, outdoor activities, and physiotherapy. They were trained on multimodal cognitive stimulation with the use of toys, art, handicrafts, drama, and music.14 A structured nutrition program provided milk, fruit juice, a hot meal of fish or chicken or mutton, and a salad, each day. Physical-exercise sessions in the afternoons consisted of gym, structured outdoor games, and free play. The enrichment also included walking field trips, basic hygiene skills, and medical inspections.15 In fact, there was an average of two and a half hours of physical activity each day. Cognitive skills focused on verbal skills, visuospatial coordination, concept formation, memory, sensation, and perception.

What happened to the control group? These kids underwent the usual Mauritian experience of attendance at petite écoles that focused on a traditional ABC curriculum.16 No lunch, milk, or structured exercise was provided. For lunch, children typically ate rice and bread.

Stratified random sampling was conducted to select which 100 of the 1,795 would enter the environmental enrichment. From the remainder, 355 controls were selected who matched the enrichment group on ten cognitive, psychophysiological, and demographic measures. We then followed up on the children for eighteen years.

What were the results? At age eleven we reassessed the children on a psychophysiological measure of attention—skin-conductance orienting. The bigger the sweat-rate response to the tones played over headphones, the greater the attention that is being paid. The two groups were matched very exactly on this measure at age three—before the intervention began.17 When they were retested eight years later, at age eleven, the enrichment group showed a 61 percent increase in orienting—a big jump in their ability to focus their attention and be alert to what was going on around them.18

We also measured their EEG—brain-wave activity—at age eleven. Brain waves can be grouped into four basic frequency bands. Right now, as you are reading this, fast-wave beta activity predominates because your brain is aroused and activated, scanning this page, absorbing the text, and forming associations. When you are relaxed, alpha predominates. When you are asleep, however, slow-wave delta activity takes over. When you are awake but not very alert, you have more sluggish theta activity. Children in general have relatively more slow-wave theta activity because their brains are immature and still developing. We found that children from the environmentally enriched group showed significantly less theta activity than the controls six years after the intervention had finished.19 Their brains had matured more and become more aroused. In developmental terms their brains were 1.1 years older than those of the controls.20

We then followed the children up for another six years, and behavior problems were assessed at age seventeen. The enriched children had significantly lower scores on ratings of conduct disorder and hyperactivity. They were less cruel to others, not so likely to pick fights, not so hot-tempered, and less likely to bully other children. In addition, they were less likely to be bouncing around the place and seeking out stimulation.21

We continued to follow them. When they were aged twentythree we interviewed all the subjects on their perpetration of criminal offending using a structured interview to measure self-reported crime.22 Those who admitted to committing a criminal offense were categorized as an offender. In addition, we also scoured every single courthouse in Mauritius and searched the records for registrations of offenses that included property damage, drug use, violence, and drunk driving—we excluded petty offenses like parking fines or a lack of vehicle registration. The enriched children showed a 34.6 percent reduction in self-reported offending compared with controls.23 For court convictions the enriched group had a much-reduced rate of offending, at 3.6 percent compared with 9.9 percent in the control group—but this difference just failed to reach statistical significance.24 The enrichment really did seem to make a difference—even twenty years later.

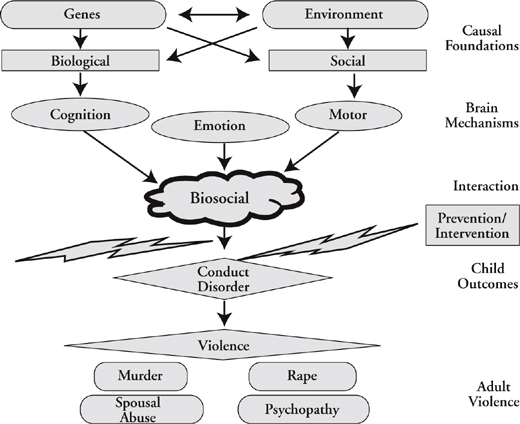

That was interesting, but something else piqued our interest even more, which you can see in Figure 9.2. You’ll recall that pediatricians had assessed the children for signs of malnutrition at age three—before the intervention had begun. On the left-hand side of the figure, kids with normal levels of nutrition at age three who went into the enrichment showed only a small and statistically nonsignificant reduction in conduct disorder. In contrast, when we looked just at those kids who entered the study with poor nutrition, we found that the enrichment showed a 52.6 percent reduction in conduct disorder at age seventeen compared with controls.25 You can see that on the right-hand side of the figure. Early nutrition status moderates the relationship between the prevention program and the antisocial outcome. It works in one group—but not in another. Recall that the prevention program had a lot of ingredients. If nutrition was the active ingredient, you’d expect the program to work more in kids who had poor nutrition at the get-go—and that’s exactly what we found.

Figure 9.2 Reductions in age seventeen conduct disorder are greater in children who had poor nutrition when they entered the enrichment

It might be that better nutrition makes the difference—but could it be something else? This was the first study to show that early environmental enrichment increases physiological attention and arousal in the long term in humans. That gives us a clue to the mechanism of action—brain change. The prevention program had more physical exercise and outdoor play, and exercise by itself could account for some of the observed effects. Exercise in animals is known to have beneficial effects on brain structure and function.26 For example, we know that in mice environmental enrichment produces neurogenesis—new brain cells growing in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus—that is entirely attributable to running.27 So it could be something as simple as the daily walks and running around in free play that the children in the enrichment group got that improved hippocampal functioning and reduced adult crime.

Another hypothesis is that the increased social interaction with positive, educated preschool teachers in the experimental enrichment may in part account for the beneficial effects. On the other hand, it may be unreasonable to focus on any single component of the intervention. Instead, the multimodal nature of the prevention program, which combined social and cognitive components alongside nutrition and exercise, may have facilitated biosocial interactions that affected later development. Just as we saw in the model, the biosocial interaction is central to the explanation of crime. Similarly, with prevention it’s a question of covering all the bases to block bullying behavior in children and violence in adults.

More intriguingly, perhaps the crime reduction can be chalked up to the young children eating fish. In Mauritius, I met with three of the original interventionists to reconstruct the typical week’s food intake for the enriched group, comparing it to that of the controls. The enriched group had more than two portions of fish extra per week. We’ve discussed in chapter 7 evidence that increased fish consumption is associated with reduced violent crime, and we’ll see later in this chapter more substantive evidence for this alternative explanation.

It’s important to emphasize that our results could not be attributed to pre-prevention group differences in temperament, cognitive ability, nutritional status, autonomic reactivity, or social adversity, which were carefully controlled for.28 The fact that the prevention program reduced crime twenty years later using two different measures of outcome—both self-reporting and objective measures—indicates the robustness of the effects. It’s unusual in the field to get results that last. Something in the enrichment is really working to reduce adult crime and violence.

Let’s also be careful about the claim. The early enrichment did not eradicate crime. It reduced it by about 35 percent—so that leaves a lot. Obviously, we need more than two years of intensive enrichment to abolish adult crime. And maybe the Mauritius miracle crime cure would not apply to other countries that have a different culture and standard of living. Yet many kids don’t get good nutrition, even in the affluent United States, and we think our findings from Mauritius may be particularly relevant to poor rural areas of the United States such as the Mississippi delta region and also to inner cities, where rates of both malnutrition and behavioral problems in children are relatively high.29

We were pleased with what was achieved and how early efforts paid off in reducing crime. At the time the study began there were no government preschools on the island at all. One lasting infrastructure contribution made by the research team, which included Peter Venables, Sarnoff Mednick, Cyril Dalais, and staff at the Mauritius Child Health Project, was embodied in the 1984 Pre-School Trust Fund Act, which established government preschools based on the two model nursery schools the group had set up in 1972.30 Currently, 183 such schools are running in five educational zones in Mauritius—and making a difference in turning Mauritius into a model African country.

The authoritarian Queen of Hearts in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was a wayward woman with a radical way of dealing with even the smallest of difficulties. “Off with their heads” was her simple solution to every misdemeanor.31 Although quite heartless, the Queen of Hearts was on the anatomical road to addressing one of the most difficult to treat classes of violent criminals—pedophiles and sex offenders. Surgical castration is the simple, radical, and highly controversial solution some authorities resorted to in order to reduce recidivism rates of sex offenders. Is this a mindless and unethical policy that should be halted? Or does it get to the heart of the matter and provide a workable solution to an intractable problem?

Surgical castration still continues in Germany, ever since a law was passed in 1970 allowing it. It’s a voluntary procedure, and only a few are performed every year. Because it sounds barbaric and is so easy to condemn, the German government has put several safeguards in place to regulate it. The offender has to be over twenty-five, and approval is needed from a panel of experts.32 Nevertheless, it remains a controversial practice in Europe. The Council of Europe’s anti-torture committee in Strasbourg, for instance, views it as a degrading treatment that should be halted. But let’s reserve judgment until we hear all sides.

It’s not only Germany that conducts castration. The Czech Republic has put over ninety inmates under the knife in the past ten years. Pavel is a case in hand. He was imprisoned at the age of eighteen after he gave in to uncontrollable sexual desires for a twelve-year-old that resulted in the boy’s death. But even before the crime he knew he had a serious problem. After waking up in the middle of the night in a sweat just two days before the murder, he sought help from his doctor. He was told that the urges would go away. But they didn’t, and apparently they became magnified as he watched a Bruce Lee movie, which stimulated his compulsion to use violence to heighten his sexual appetite. He took a knife to the boy and killed him.

After eleven years in prison and psychiatric institutions in the Czech Republic, and just one year before he was due to be released, Pavel asked to be surgically castrated. “I can finally live knowing that I am no harm to anybody,” he reported after the procedure. “I am living a productive life. I want to tell people that there is help.”33 Pavel now loves his life in Prague, working as a gardener for a Catholic charity.

For Pavel, removal of his testicles was the price he paid for peace of mind, even if it meant being alone, with neither sex nor romance. It’s a tough life, but nevertheless a life that gives him meaning and some degree of dignity. Isn’t that better than rotting away in prison, or living every day being torn apart by the wild horses inside that are urging you to desecrate the body of an innocent child?

Debates over the ethics of castration are heated and inevitably revolve around prisoners’ rights and the benefits to the individual and society. Let’s leave aside the ethics for now, which can be debated at length. Here we’ll take a cold, calculated look at the empirical evidence for and against the efficacy of this drastic intervention. Does it work? If it does not make a difference, that would be a compelling argument for eradication of this drastic—and some would say draconian—form of treatment.

We saw earlier how high levels of testosterone are associated with increased aggression, yet these data are correlational, not causal. The etiological assumption behind castration is that lowering testosterone and thus sex drive would lower reconviction rates in sex offenders. But does it?

Good studies of the effects of castration in human prisoners are few and far between. Ethically, you cannot randomly assign one sex offender to castration and one to an alternative treatment. The study that comes the closest to the impossibly ideal experiment was conducted by the medical researchers Reinhard Wille and Klaus M. Beier in Germany in the 1980s.34 Wille and Beier followed up ninety-nine castrated sex offenders and thirty-five non-castrated sex offenders for, on average, eleven years after release from prison. Such a sample covers about 25 percent of all castrations in the period from 1970 to 1980, and is therefore reasonably representative of this population. Subjects could not be randomly assigned to experimental and control conditions as would be demanded by a rigorous randomized controlled trial. Nevertheless, the thirty-five controls had all requested castration—but ended up changing their minds. As such they constitute as close a control group as can be ethically achieved.

Recidivism rates for sexual offenses over the eleven-year post-release period were 3 percent in castrated offenders compared with 46 percent in the non-castrated offenders—a dramatic fifteenfold difference. The 3 percent reconviction rate in castrated sex offenders is consistent with rates found in other studies that have not been as rigorous as that of Wille and Beier. Rates of reconviction in castrated sex offenders from these ten other castration studies range from 0 percent to 11 percent, with a median of 3.5 percent. These data provide further support for considerably lower reconviction rates in castrated sex offenders. Bear in mind that 70 percent of castrates in Wille and Beier’s study were satisfied with their treatment. It’s certainly not a panacea for pedophilia and other sexual offences, but should it be entirely ruled out if appropriate safeguards can be guaranteed?

What about the wider literature? One review of 2,055 castrated European sex offenders showed recidivism rates ranging from 0 percent to 7.4 percent over a period of twenty years,35 results very similar to those in the Wille and Beier study. Yet another review, by Linda Weinberger, a professor of clinical psychiatry at USC, documents the low incidence of sexual recidivism following physical castration in many different countries, commenting that “the studies of bilateral orchiectomy are compelling in the very low rates of sexual recidivism demonstrated among released sex offenders.”36 At the same time she cautions that it is hard to generalize to present-day high-risk offenders, and recognizes the ethical difficulties. However, a commentary on this review cautions that it is important not to underestimate the potential importance of castration when considering the release of an offender.37

It sounds grotesque, doesn’t it? The holier-than-thou among you will be wringing your hands in horror at the barbarity of this surgical intervention. But you don’t have to live your life as a pedophile in a top-security prison, do you? You don’t have to face the daily taunts—and danger of being raped—that these men face. You don’t have your mug shot on the Web for all to see after your release so that people know exactly where you live. You don’t have to be responsible for controlling sexual urges that are very difficult to contain. Shouldn’t people like Pavel at least be given the option of castration under conditions guaranteed to have no external coercion?

Fortunately—or perhaps unfortunately, depending on your perspective—there are less drastic methods of dealing with sexual offenders: chemical castration. Here anti-androgen medication is given to reduce testosterone—and hence lower both sexual interest and performance. In the United States medroxyprogesterone—or Depo-Provera—is used to increase circulating progesterone. In the United Kingdom and Europe, cyproterone acetate is used, which competes with testosterone at androgen receptors in the brain. Other medications include leuprolide, goserelin, and tryptorelin. In all cases, they reduce testosterone to prepubertal levels.

Nobody actually doubts that these medications significantly reduce sexual interest and performance. Yet again, the methodological and scientific issue is whether they reduce re-offending. Friedrich Lösel at the Institute of Criminology at Cambridge University conducted a meta-analysis and concluded that the effects of chemical castration are actually stronger than with other treatment approaches, a very telling result.38

Because it is somewhat less controversial than physical castration, chemical castration is offered in Britain, Denmark, and Sweden on a voluntary basis to sex offenders. Nevertheless, policy became tougher in Poland since 2009, when offenders who rape either a child under the age of fifteen or a close relative have to undergo chemical castration after release from prison.39 This came about in part after a man was accused of having two children with his young daughter—akin to the case of Josef Fritzl in Austria. Eighty-four percent of the Polish population supported the policy.40 In South Korea, a new law was put into effect in July 2011 that allows judges to sentence offenders who have committed crimes against children under sixteen to receive chemical castration. In Russia, chemical castration can be recommended by a court-appointed forensic psychiatrist for those who have attacked children under the age of fourteen.41

In the United States, at least eight states have had laws on chemical castration ever since it was introduced into the Penal Code of California in 1996. In both California and Florida, treatment with Depo-Provera is mandatory for repeat sex offenders and may also be used in some cases with first-time offenders, such as those who have committed a sex crime against children under the age of thirteen. In California, treatment is administered by the Department of Corrections and must begin a week before the parolee is released. It must be continued until the Department of Corrections deems that the offender no longer needs treatment.42 In Wisconsin, the Department of Corrections can prevent the release of a child sex offender if he refuses to undergo chemical castration.43 Texas, like Germany, allows surgical castration on a voluntary basis, and, as with Germany, safety procedures are put in place. Offenders must be older than twenty-one, have at least two prior sex-offense convictions, have undergone at least eighteen months of other treatment, and also understand the side effects of the surgery.

The debate is heated. The American Civil Liberties Union argues that chemical castration violates sex offenders’ constitutional rights that pertain to privacy, due process, and equal protection, and the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Others argue that with appropriate controls the treatment is in the best interest of both the individual and society. One editorial in the British Medical Journal argued that doctors should avoid becoming agents of social control, and documented the potential side effects of castration, including osteoporosis, weight gain, and cardiovascular disease. At the same time, this editorial argued that when the individual has sexual urges that are hard to control, biological treatment makes sense. The editorial argued that anti-androgen drugs are effective and that offenders are capable of making an informed choice on whether or not to take the drugs. Furthermore, it went on, while some argue that freedom of choice may be lost when the prisoner has to choose between long-term detention and drugs, prisoners should be given a choice, and preventing this choice borders on the ethically questionable.44

You can answer the question yourself. Imagine you are a sex offender in prison with murderers, rapists, and psychopaths. Would you like to be allowed a choice—a choice between long-term detention, or chemical castration and release?

Nobody is coercing you right now in pondering the answer. You are free to decide. I know what I’d want. I think if you had spent four years in top-security prisons as I have you’d want to be allowed to make a decision and you would want chemical castration. Or perhaps you think that sex offenders are beneath contempt and should rot in hell.

One of the problems with chemical castration is that it affects our right to reproduce. It goes against our evolutionary makeup and mind-set. There is another alternative. What if we stay with the medical model for treatment of offenders but we do not compromise their ability to have children? We’ll take a journey to explore this further.

You never know what might happen when you get on a plane. Every time I walk down that gangway, images of unforeseen disasters flit through my mind. But before I go on, let me introduce you to my boyhood hero, Tintin. This sixteen-year-old newspaper reporter was the invention of Hergé, a Belgian writer and cartoonist who was an important influence not just on myself but also on Andy Warhol.45 Tintin’s life revolves around writing crime stories and traveling internationally to solve mysteries. He is a boyish, avant-garde swashbuckler who pushes the envelope on puzzles to stop crime—and has fun at the same time. I was brought up with Tintin as a boy. I bought all the Tintin books. I tracked down Hergé in person and got him to sign several of my books, including Flight 714. And here I am today, a boy trapped in an adult’s body, writing about the causes of crime and traveling the world to stop it.

Now to Flight 714—the penultimate story in the twenty-three-volume Tintin series. Tintin is in the tropics in Jakarta and catching a plane to Sydney with an eccentric millionaire. A fight breaks out and the plane gets hijacked by terrorists. The criminals want the millionaire to spill his bank account number. He’s injected with a truth drug by the dastardly Dr. Krollspell—a sort of Josef Mengele parody—under the orders of his evil boss, Roberto Rastapopoulos. That’s where the medication comes in.

Now cut to my story. As with Tintin it begins benignly enough. I got on board United flight 895 bound to another tropical country—Hong Kong—on Thursday, July 17, 2007. I settled into my bulkhead aisle seat, had my dinner, and then sank into reading Jonathan Kellerman’s Rage. An academic detective crime story, of course. And that’s when it happened.

There was an urgently ominous announcement: “We have a situation. If there is a doctor or—[pause]—a psychologist on board, could you please make yourself known to the flight attendant.”

I got a queasy feeling and it wasn’t my dinner. Usually they want a doctor, but they also said “psychologist.” Well, I might be a psychologist, but I’m also a wimp. The truth is that just before that announcement I heard a racket coming from the section ahead of me past the toilets on the port side. It had distracted me from my book. Then two flight attendants zipped past me. Even more yelling. Maybe Rastapopoulos was on board.

I took a look back up the long aisle behind me to check the passenger seat lights. Come on. Surely there had to be a doctor on board. Was anyone coming to the rescue? But the aisle lights were as dark as a graveyard. I turned back in my seat and began to feel a bit desperate. It seemed like the sort of thing Jonathan Kellerman could solve. He’s a psychologist as well as a best-selling crime writer. Maybe he was on board? Maybe there was a Dr. Krollspell lurking in the wings. I looked behind me again. All I could see was a sea of faces looking up the aisle at me to see what was going on beyond me.

Think, Raine, think, you idiot. I thought it through carefully. I decided on the only sensible, professional, and responsible course of action for a professor in criminology. I kept reading Kellerman.

You know what, though? You look up from your book, gaze into space, and say to yourself, “You cowardy custard.” Emotional quicksand was quickly covering me in a suffocating swathe of guilt. I looked around again. Not a blinking sausage, no cavalry. I wasn’t the only wimp. Okay, to hell with it, here goes. I rang my bell.

There certainly had been a brawl. I walked with the flight attendant up to the front, where a scuffle was still taking place between a male flight attendant and a passenger. My escort gave me a comprehensive, articulate, and professional appraisal of the situation: “He just went nuts and whacked the woman next to him!” I was behind the desperado, so I pinned his arms behind his back while the attendant whipped his tie off. In a jiffy we’d tied the assailant’s arms behind his back. The woman was still yelling, but we ignored her, as it was all Chinese. We shoved our prisoner into a window seat. I jammed myself beside him, with the steward next to me to block up the aisle seat. We had secured the situation.

The next thing I know the steward had me switch seats because the pilot wanted to talk to me. They brought me to the cockpit. And that’s where the cool bit began and I got to feel like I was Tintin. They wanted to patch me through on the intercom to an MD on the ground. The pilot got out of his seat, I jumped into it, and he instructed me on how to work the communications system. Have you seen Steven Spielberg’s movie The Adventures of Tintin? Remember when Tintin is in the pilot’s seat? The confined space. The instrument panel dazzling your eyes at one level. Then you gaze out of the cockpit window and you’re floating on those fluffy white clouds. So very much at peace, so Tintinesque, gliding up there in heaven above the hot struggles of the poor. It’s what a British Airways ex-accountant always wanted.

The duty doctor down below snapped me out of it. He knew I was an expert on violence and a psychologist. What’s my professional evaluation of the level of danger to other passengers? How can we secure the situation? I say we can deal with it by giving the guy a hefty dose of my Temazepam—a short-acting benzodiazepine. I always bring it on board international flights because I have trouble sleeping on planes due to the noise at night—you know—owing to having my throat cut that night in Turkey. I suggest a good dose, 30 milligrams. The doctor thinks 15 milligrams. We ended up with the 15 milligrams—and that did help calm the villain down. Then we made an emergency landing in Anchorage so that security forces could board the plane and offload the blighter.

I have to say I felt pretty good about it. As the other passengers lined up to land in Hong Kong, I was slapped on the back by the copilot and applauded. United flew me business class for the rest of my round-the-world journey. All in a day’s work as a criminologist, I said. Yup, my boyhood Tintin dreams had finally come true.

But back to medication. It really does arrest aggression. Unlike in the case of flight 895 I’m not talking about sedation to quell violence. We’ve witnessed major advances in psychopharmacology together with substantive evidence that some medications are surprisingly effective in reducing aggressive and violent behavior.

Let’s start with children. What’s the most common cause of children under the age of nine being referred for psychiatric services? It’s none other than behavior problems.46 The majority of these hospitalized children are receiving medication to treat aggression.47 Clinical practice is backed up by surprisingly strong empirical support for the effectiveness of drugs as an intervention for childhood aggression. A meta-analysis of forty-five randomized, placebo-controlled trials conducted in children by Elizabeth Pappadopulos48—not to be confused with Rastapopoulos—has shown that medications are surprisingly effective in treating aggression, with an overall effect size of 0.56—which is of medium size in terms of the strength of the relationship.49

A wide variety of medications have been found to be effective in reducing aggression. The most effective are the newer generation of antipsychotics,50 which show a large effect size of .90.51 Stimulants like methylphenidate are also very effective, with an effect size of .78.52 Mood stabilizers have a medium effect size of .40, while antidepressants have a small-to-medium effect size of .30. The same story that we see in children holds true in adolescents.53 Two meta-analyses of drug treatments of aggression in juveniles, together with other reviews and meta-analyses of drug efficacy with aggression and antisocial behavior in child and adolescent populations all show the same story.54, 55, 56 What’s clear is that drug treatment is effective in reducing aggression across a wide range of psychiatric conditions in childhood and adolescence—including ADHD, autism, bipolar disorder, mental retardation, and schizophrenia.57

How does medication compare to nonmedical treatment of aggressive and violent behavior? My colleague Tim Beck, in my department at the University of Pennsylvania, originally developed cognitive-behavior therapy, which is widely effective in treating a whole range of clinical disorders. It is the most effective and well-accepted treatment for aggression. The overall effect size? Conservatively it is .30.58 So the overall effect sizes obtained for medications compare very well to the best psychosocial interventions.59 Indeed, effect sizes for atypical antipsychotics and stimulants if anything exceed the best non-pharmacological treatments.

Skeptics will scrutinize this claim assiduously and can come up with a reasonable retort. Perhaps the medications are treating other conditions like depression, ADHD, and psychosis that aggressive children also have, and that accounts for the reduction in aggression. For example, children with psychosis get crazy ideas into their heads about other kids picking on them, so they strike out in a defensive, aggressive rage. So yes, risperidone works well in reducing the aggression because it’s cutting out the craziness—one cause of the aggression. However, many studies have clearly demonstrated the effectiveness of medications with children coming to the clinic primarily with antisocial/aggressive behavior rather than psychosis.60 Meta-analyses of the literature also show that stimulants reduce aggression independent of their effect in reducing ADHD symptoms.61 There is even evidence that stimulants and atypical antipsychotics are effective in reducing aggression in preschoolers.62 It’s a bitter pill for many criminologists and psychologists to swallow, but medications do work in controlling and regulating aggression in children and adolescents.

Can medications work too in quelling outbursts in adults? Surprisingly, there is much less research here, probably because once you become an adult and are violent, you are viewed as evil and we lock you up. We don’t want to help you anymore. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial allocated impulsive aggressive male community volunteers to one of three anticonvulsants.63 All three medications significantly reduced aggressive behavior.64 The same result has been found in several randomized controlled trials for treating impulsive forms of aggression in prisoners.65

Why on earth would anticonvulsants, normally used to stop epileptic seizures, work with reducing aggression? We know these medications have a calming effect on the limbic regions of the brain—particularly the amygdala and hippocampus, where epileptic seizures begin. We saw earlier that impulsive, emotional murderers have excessive activation of these limbic subcortical regions, so anticonvulsants may help reduce their impulsive emotional rage attacks by calming their emotional limbic system.

Let’s continue our travels to find a different cure to crime. La Pirogue is the jewel in the crown of the beautiful island of Mauritius. With its golden sands and tropical gardens surrounding traditional-style thatched rooms, it is a haven of peace and tranquillity. It is my favorite hotel in the world.

Utoeya is also a utopian picturesque island, this one located in the Tyrifjorden fjord outside of Oslo in Norway. With its pretty little beaches it is similarly a summertime resort for young people. And it was here on the evening of July 22, 2011, that eighty-four people lost their lives while I unknowingly sat on the beach at La Pirogue in Mauritius, watching the sun set slowly over the coral reef.

I had flown in just the day before on flight MK 647 from Singapore, where I had been working with my colleagues on our fish-oil study on conduct-disordered children. The biotech company Smartfish, whose headquarters are in the Oslo Innovation Center, supplied the Joint Child Health Project in Mauritius with an omega-3 drink. I had a connection with its cofounder Janne Sande Mathisen, as she had gone to Darlington Technical College, which was just a few blocks from 69 Abbey Road, the house I was brought up in as a child. I had an unexpected e-mail from her on that fateful day:

Just 20 minutes ago there was an enormous explosion in central Oslo—affecting the governmental buildings. We could hear the explosion even though we live 20 minutes (by car) from the center. It is most likely a bomb and a terror attack. This has never happened before, and it will have strong impact here.

What Janne had heard was a massive blast from a 2,000-pound fertilizer car bomb placed in the center of Oslo, which exploded at 3:17 p.m., damaging ministry buildings including the prime minister’s offices and killing eight people.

A short while after, at about five p.m., an armed “policeman” took a ferry across the Tyrifjorden fjord just outside of Oslo to the island of Utoeya to “investigate” the bombing. Landing on the island, which was filled with teenagers taking part in a youth camp for the Labor Party, he called the students toward him. They dutifully came, whereupon he promptly shot them. Anders Behring Breivik continued his shooting spree for an hour, during which time he killed sixty-nine individuals, mostly teenagers, fifty-six of them shot in the head. Thirty-three more were shot but survived. It was the worst peacetime massacre in Norway’s modern history.

Those victims had been drawn to that island for its charm and peace, to relax in the countryside and beaches just as I was doing in Mauritius. Yet as I sat in my paradise watching the sun setting over the Indian Ocean, their paradise was being invaded by a sandy-haired, blue-eyed devil. As I heard the crashing of the waves on the coral barrier reef outside my room at La Pirogue, there was the crushing of their young souls outside Oslo. Yet in the sea in both Norway and Mauritius there might just be a part-solution to this kind of mindless violence—fish.

I first got the idea on a visit to Mauritius a decade ago. It was November 2002, and I had just revised our findings from our earlier study showing how early environmental enrichment particularly reduced conduct disorder in kids with poor nutrition—an enrichment that included more fish. I was in the airport in Mauritius, wanting to buy something to read on the plane going to Hong Kong. There is one, and only one, small book shop there, and it largely sells books in French. There were literally two short shelves with books in English. And there I saw it, Andrew Stoll’s The Omega-3 Connection,66 which had come out the previous year.

Going through it on the flight, I read his summary on the early studies suggesting that omega-3 might help with depression, ADHD, and learning difficulties. There were no studies of aggression or antisocial behavior, but he speculated:

We await the results of future studies in our nation’s schools and prisons, and hope that at least part of the answer may be as simple as an omega-3 fatty acid.67

Perhaps he was right. The staff at the Joint Child Health Study in Mauritius tested the idea in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of omega-3 supplementation in children and adolescents. Participants were drawn from the Mauritius Child Health Project. One hundred children drank one pack of the Norwegian Smartfish Recharge juice per day. It’s only a 200-millileter drink (less than a cup), but packed into it is a whole gram of omega-3. They took that for six months. One hundred other children were randomized into the placebo control group and received the same juice drink, but lacking the omega-3. Parents then rated their children’s behavior problems at the beginning of the study, six months later (at the very end of the treatment), and for a third time six months after the treatment had ended.

The results were intriguing. As you can see in Figure 9.3, both groups showed a reduction in aggression after six months of taking the drinks. That shows there was a placebo effect—that the fruit-juice drink without the omega-3 was doing just as good a job as the omega-3 drink. However, six months after the end of the treatment, the control group had returned almost to its pretreatment levels of aggression, whereas the omega-3 group continued to show even further reductions in aggression, delinquency, and attention problems. It was a significant interaction between treatment group and time, with the groups really diverging in outcome a full year after the study had begun.68 These results provide some initial support for the idea that omega-3 can help in the long term in reducing behavior problems in children, a significant precursor of adult crime and violence.

Figure 9.3 The long-term effect of omega-3 in reducing aggression in children

Why would we expect omega-3 to reduce aggression? In a way it’s surprisingly simple. We’ve seen throughout this book that there is a brain basis to violence. We discussed earlier how omega-3 enhances brain structure and function by increasing dendritic branching, enhancing synaptic functioning, boosting cell size, protecting the neuron from cell death, and regulating both neurotransmitter functioning and gene expression. So omega-3 might partly reverse the brain dysfunction that predisposes one to aggression.

I was initially surprised that there would be a long-term change. Wouldn’t any initial results wash out after the Smartfish drink was discontinued? But Joe Hibbeln, a leading figure in the field, explained to me that the half-life of omega-3 in the body could be about two years—it stays in the body ready for re-uptake and it can make a lasting change in the brain.69 So it stands to reason, at least in theory, that by improving brain structure and function omega-3 could help reduce violence in the long term.

The idea that nutrition could help is not new. In 1789, when the revolting French peasants in Versailles were baying for the blood of their queen, Marie Antoinette is reputed to have said, “If they have no bread, then let them eat cake.” Brioche—a rich form of bread that she was supposedly referring to, may not have helped much, but she wasn’t that far off the mark in thinking that nutrition could quell the violent rioting. And omega-3 is not just food for thought, it’s increasingly becoming food for court.70 The judiciary are becoming interested in the idea that omega-3 can cut crime.

Skeptical? So far two randomized controlled trials have shown that omega-3 supplementation can reduce serious offending within a prison. The first study, by Bernard Gesch, at Oxford University, demonstrated that taking a combination of omega-3 and multivitamin supplements for five months led to a 35 percent reduction in serious offending in young adult prisoners.71 Fascinated by these initial findings, the Ministry of Justice in The Hague in the Netherlands conducted its own study on young-adult offenders and found that omega-3 and multivitamins for eleven weeks reduced serious offending within the prison by 34 percent—results almost identical to the British study.72

Wherever you go around the world, it seems that omega-3 may make a difference. In Australia, six weeks of omega-3 supplementation reduced externalizing behavior problems in juveniles with bipolar disorder.73 In Italy, normal adults taking omega-3 for five weeks showed a significant reduction in aggression compared to controls.74 In Japan, a randomized controlled trial of omega-3 in adults reduced aggression.75 In Sweden, a randomized controlled trial found that ADHD children with oppositional defiant disorder showed a 36 percent reduction in their oppositional behavior after fifteen weeks of omega-3.76 In Thailand, a randomized, double-blind trial of the omega-3 fatty acid DHA resulted in a significant reduction in aggression in adult university workers.77 In the United States, women with borderline personality disorder randomized into supplementation of the fatty acid EPA for two months showed a significant reduction in aggression.78 Another American study, this time a four-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fatty-acid supplementation in fifty children, showed a significant 42.7 percent reduction in conduct-disorder problems.79

It’s all too simple, you say. And strictly speaking you are right. Violence is complex. In omega-3 we are looking at only one ingredient of a much bigger nutritional package that can feed violence-intervention efforts. We saw earlier how eating candy is correlated with crime. Blood-sugar lows can blow the lid off containing aggression. Not eating enough can make one tough. Micronutrient supplementation of both zinc and iron helps accelerate recovery of hippocampal functioning following iron deficiency in rats.80 We also know that a lack of protein results in EFA (essential fatty acids) deficiency, while micronutrient deficiencies contribute to impaired EFA bioavailability and metabolism.81 You’re right, it’s not simple.

Omega-3 is certainly not the sole solution on the nutrition front—there are many more nutritional factors to consider. And nutrition itself is just one piece of the much bigger jigsaw puzzle. Not all omega-3 studies have come up trumps.82 Nevertheless, these international findings are initial appetizers that should tempt us to consider further how nutrition can nix crime and violence. A body of knowledge is being built up that gives us an alternative perspective to drugs as a solution. Societal distaste for any “Prozac for prisoners” proposition could be tempered by the more palatable alternative medical approach of “fish for felons.” It could potentially prevent future disasters.

Anders Behring Breivik was initially argued to have a psychotic disorder—paranoid schizophrenia—that resulted in the Norwegian tragedy. We discussed earlier how schizophrenia is related to violence. Is it entirely a coincidence that the very first study to prevent the development of psychosis in adolescents and young adults was based on omega-3?83 Is it a coincidence that the early environmental enrichment in Mauritius that included an extra two and a half portions per week reduced not just adult crime, but also adult schizophrenia-spectrum personality traits, especially in those who had poor levels of nutrition before the enrichment?84 Future studies following the Norwegian Smartfish study on the island of Mauritius may ultimately provide prevention of slayings like the ones that took place on Utoeya island in Norway.

Changing the brain to change violence may not necessarily require drugs or any invasive form of therapy—or even more benign biological interventions such as nutritional change. Let’s turn back to biofeedback and Danny. By feeding back to him his brain activity, he was able to learn how to increase activation of the prefrontal cortex. That gave him agency and the ability to better regulate his behavior. But can biofeedback like this really stop violence?

Research on individuals with antisocial personality disorder claims to show that intensive EEG biofeedback involving from 80 to 120 sessions does improve their behavior.85 That is promising, but the clear limitation is that to date much of the evidence is based on case studies. Randomized controlled trials are needed to more conclusively demonstrate efficacy. We still have a long way to go with this particular biological intervention.

But Buddha may help put us on the path to permanent brain change without drugs or invasive treatment. Mind over matter. Maybe meditation can change the brain for the better.

The technique itself is fairly simple. You would have one training session for eight weeks, each one lasting about two hours. You would practice the technique one hour a day at home, six days a week.86 You would be taught to become more aware—or more mindful—of your internal mental and bodily state. Attention might, for example, be focused on breathing, becoming more aware of your present-moment experiences, and mindfully going through your whole body’s sensations and feelings. You are taught to take a compassionate, nonjudgmental stance to yourself—to not, for example, beat yourself up during training if your mind wanders from the task. Later on you would be taught to become aware of yourself in the here and now.87

Doing all that will change your brain—permanently. In 2003, a leading neuroscientist, Richie Davidson, from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, performed a breakthrough meditation study. People were randomized into either a mindfulness training group or a control group that was put on a waiting list for training. Richie demonstrated that just eight weekly sessions of mindfulness training enhanced left frontal EEG activity.88 Manipulate the brain through mindfulness, and better mood and psychological functioning can result.

One study from Davidson’s group showed how focusing on a mental state of compassion and loving kindness for others enhanced brain regions involved in empathy and mind-reading. Participants’ ability to process emotional stimuli was enhanced, bringing on line the amygdala and the temporal-parietal junction of the brain.89 Functional imaging research has also shown that expert meditators have greater activation in brain regions involved in attention and inhibition.90

It’s not just that meditation changes the brain during the time of meditation. People who have practiced meditation over a long period later show that at rest—in a non-meditation state—their brain has shifted toward increased attention and alertness as measured by gamma activity—a form of high-frequency EEG activity involved in consciousness, attention, and learning.91 The more hours of practice, the greater the brain change taking place. Meditation is producing long-lasting positive effects on the brain.

Mindfulness practice changes not just brain function but also brain structure. One study scanned subjects before and after an eight-week mindfulness course, with controls again being put on a waiting list. The mindfulness group showed a significant increase in the density of cortical gray matter after treatment—a tangible physical change.92 Enhanced areas included the posterior cingulate and the temporal-parietal junction, areas involved in moral decision-making. The hippocampus was also enhanced, an area critical for learning, memory, conditioning, and aggression regulation93 and that is impaired by extreme stress.94 So even though the hippocampus reaches full maturity early in life,95 its structure can still be enhanced through later environmental change. Another brain-imaging study documented that extensive meditators have increased cortical thickness in the prefrontal cortex compared to controls.96 Mindfulness remodels the brain—physically.

Hold in your mind for a while the evidence that meditation can change your brain. Now let’s ask whether it changes crime and violence. Perhaps surprisingly, meditation training with prisoners has been going on for quite some time. Transcendental Meditation (TM)was made popular during the swinging ’60s by its founder, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, a charismatic figure who was a guru to the Beatles. By the beginning of the 1970s it was already practiced in California prisons.97 Since then meditation studies have spread to Texas,98 Massachusetts,99 and India.100 Scientific reviews have argued that meditation in prisoners reduces their anxiety and stress levels, increases their psychological well-being, and reduces their anger and hostility. More important, one literature review on meditation in offenders has argued for not just a reduction in post-release drug and alcohol use, but also reduced recidivism.101 Even women arrested for domestic violence have shown reduced aggression, alcohol use, and drug use after twelve sessions of mindfulness training.102

One large-scale study gave mindfulness training to 1,350 inmates and showed significant reductions in their hostility, aggression, and other negative moods. Interestingly, the improvements were stronger in women than in men. Among the men, improvements were stronger for minimum-security prisoners than for maximum-security prisoners—although all groups did improve. It seems that meditation most helps offenders who are not so severely criminal. One recent randomized controlled trial in normal adults, most of whom were female, showed that mindfulness significantly reduces anger expression and improves the ability to regulate emotions.103 It might be therefore that this intervention could particularly help female offenders.

What are we to make of this? The claims are intriguing, but the reality is that we sorely need a randomized controlled trial to demonstrate that mindfulness training really can reduce violence. Unlike the studies by Davidson and others on brain change, no such study appears to have been conducted on offenders. Granted, Transcendental Meditation has a funky past, with its prior claims of levitation abilities and other supernormal powers. Mindfulness meditation, with its origins in Buddhism, might also seem quirky by association with the TM movement. Yet there is now unquestionably a strong body of scientific support—based on randomized controlled trials—documenting its efficacy in reducing anxiety and stress,104 substance use,105 depression, and smoking,106 and in increasing positive emotions.107 It’s a promising technique that is gaining in scientific credibility, and it cannot be ignored.

Let’s suppose for a minute that it’s not all pie in the sky. Now put in your mind the hypothesis that mindfulness and other meditation techniques can really reduce violence. How might mindfulness and other meditation techniques work? What might be the mechanism of action? Recall that you are taught to become more aware of your own thinking.108 You become increasingly conscious of when you are beginning to feel angry over a disparaging comment someone makes to you. You become better able to regulate your thoughts before you boil over in a rage. You become more attuned to the very first moments when, say, your partner made that critical comment that cascaded into a steady stream of unpleasant thoughts and associations. You become aware of your heart racing and your face flushing, and how negative emotions then rear their ugly heads. You are taught to become more accepting of these feelings, to control the urge to act, and to step back from your first instinctive emotional reactions. Because you have become adept at experiencing the negative thoughts and emotions that you felt when the argument started, you have learned to habituate or acclimate to them. That means you can better control your urge to lash out. By being more mindful of your anger at an early stage, you are better able to control and regulate it—at a point in time when your anger is more manageable and has not yet reached its crescendo.

If you think back at the neuroscience we looked at—the studies that document both the short-term and the long-term brain changes that occur with mindfulness—the effect of meditation begins to make some sense. Meditation enhances left frontal brain activity. That meshes with the fact that enhanced left frontal brain activation occurs when people experience positive emotions109 and is associated with reduced anxiety.110 It also increases frontal cortical thickness, and we know that this area is not just important in emotion regulation, but is also structurally and functionally impaired in offenders. Note also that meditation enhances brain areas important for moral decision-making as well as areas involved in attention, learning, and memory. We have seen that offenders have impairments in these cognitive functions. Meditation is improving brain areas involved in functions that are deficient in offenders, and that’s why it may help.

Mind over brain matters. Brain over behavior matters. What matters to me is that hopefully in journeying through the anatomy of violence you have appreciated three important points. First, there is a basis to violence in the brain. Second, the biosocial jigsaw mix is critical. Third, we really can change the brain to change behavior.

In that third point we have options that run the gamut from concrete surgical castration to almost spiritual mind-over-matter training. In between these extremes we have prenatal nursing interventions, early environmental enrichment, medication, and nutritional supplements that can all make a difference.

Based on the biosocial model I’ve outlined here, we have promising techniques to block the foundational processes that result in the brain dysfunctions that in turn predispose an individual to violence. That has not been fully recognized within the traditional study of crime—and it really needs to be if we are to be sincere about stopping the suffering and pain associated with violence. We can wait until the milk is already spilled and we have to deal with the adult recidivistic offender who is so very hard to change. That’s where we are today. Or we can invest in broad-based prevention programs that start in infancy and can benefit everyone—a public-health approach to violence prevention.

Ultimately, it is up to the public to make that decision. If you want my personal view—based on everything I have learned in my thirty-five-year career in research and practice—it would be this: the best investment that society can possibly make in stopping violence is to invest in the early years of the growing child—and that investment must be biosocial in nature. You cannot successfully intervene without addressing the brain.

Don’t get me wrong. Biology is not the sole answer to stopping violence and never will be. Larry Sherman, a world-renowned experimental criminologist at Cambridge University, and others have marshaled systematic evidence from randomized controlled trials documenting that some traditional psychosocial and behavioral treatment programs can make a modest difference in offending.111 What I am arguing here does not negate the positive work done to date by experimental criminologists. What I am saying, however, is that we can go one better with biological interventions that take into account the anatomy of violence—and break the mold that is today giving birth to violent offenders in droves. We have much research ahead of us to develop new and innovative biosocial interventions, but we now have a base on which to build—if we are willing to.

Imagine how society would change if for once we could cure crime. Can you picture a future where suddenly we crack the biological code to violence? How would that change how we think about violence? How would it affect our sense of culpability, punishment, and free will? Would it lead to changes in the law? We’ll see in the next chapter that this future isn’t so far away.