Figure 12.1 Human behaviour: Adjusting the framework for culture, context and the body

Restorative dance/movement psychotherapy with survivors of relational trauma

Amber Gray

Exposure to traumatic events is life changing. Fifty years ago, survivors of trauma did not have a diagnosis to explain their suffering. The symptoms, or signs of distress, that occur when a body, or system, is held captive by fear or ‘locked down’ in terror, were observed but not adequately categorized or inclusive enough to aid survivors to have a context for their experiences of suffering. Today, the field of trauma has advanced, and we now know that those exposed to what seem like more frequent events on the planet, for example experiences of school shootings, wars, genocide, domestic violence, torture, natural disaster, terrorism, sadistic and ritual abuse, sudden loss, accidents, and all other manner of fear, provoke life changing events in which people are forever changed.

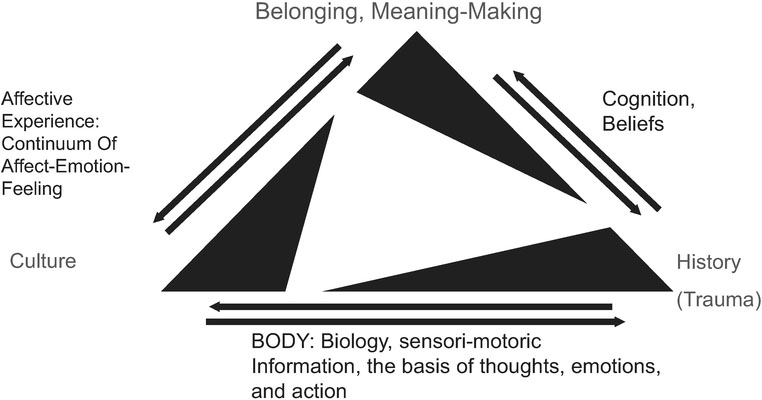

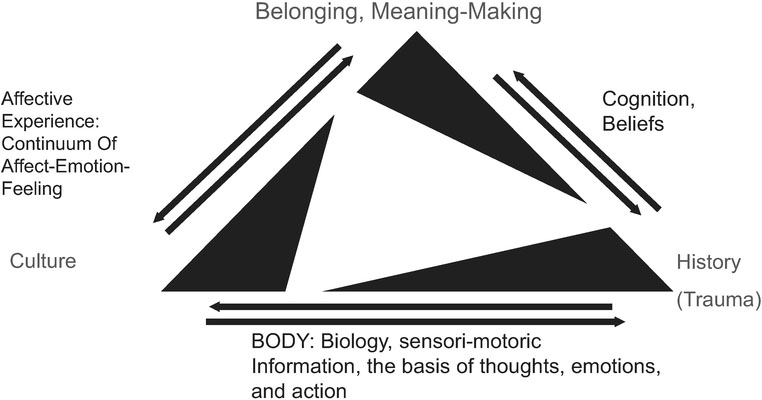

We do not ‘recover’ from trauma; we do not go back to being the same. This is not to suggest we do not continue our lives with enthusiasm and enjoyment; in fact, traumatic events can catalyze change and transformations of great meaning for survivors. To expect this as an outcome of treatment, however, can be unfair to survivors of extreme events who endure ongoing loss, isolation, and complex psychological and physical pain. We also do not release trauma; we now know that the shifts that occur in the moment of exposure are somatic (biological, physiological) and there are many body-based approaches that utilize the body’s ability to discharge nervous system charge, or activation. This author suggests the healing occurring after life changing events, such as relational trauma, beg a restorative process, where we restore what aspects we can of a survivor’s life in service of restoring a sense of belonging and meaning (see Figure 12.1). Approaches that remain solely cognitive, affective, or behavioral will not offer a thorough restorative process, because the imprint of fear is in the body.

Whether the exposure is violence, natural disaster, or an accident, we now know that the imprint of the fear response that occurs in the moment of exposure (i.e. the traumatic experience) is body-based. Current neuropsychiatric research endorses the use of non-verbal therapies for work with survivors of trauma, recognizing that trauma memories are implicit. Dance/movement therapy (DMT) acknowledges the body as central to human experience, and movement as a primary language, fundamental to our early communicational relationship with caregivers. Knowing that trauma changes the brain, recent scientific discoveries in interpersonal neurobiology and neuroplasticity promote mindfulness or contemplative practice, and movement, as the most effective brain changers (Begley, 2007). Movement, as a primary language, and dance, as its creative expression, access the neurological underpinnings of all human thoughts, feelings, actions, and behaviors. DMT has a unique contribution to make in the growing convergence of science, theory, and clinical practice for trauma; the therapist’s capacity and skill to promote interoceptive awareness and mindful movement, which are essential for healing, may promote our therapeutic approach as best or promising practice in the growing field of trauma. Relational trauma can literally force us to take a shape that is not our own; through work with posture, core support, effort shapes, rhythm, and sensori-motoric developmental sequences, the therapist can support traumatized clients to restore meaning and their place of belonging in the world. This chapter presents a framework, The ‘Poto Mitan’ Framework for Trauma and Resiliency (Gray, 2015a), and its clinical counterpart, Restorative Movement Psychotherapy (RTP), as a potential best practice approach to the restorative process with survivors of relational trauma.

Figure 12.1 Human behaviour: Adjusting the framework for culture, context and the body

Dance/movement therapy is an integrative and holistic approach to psychotherapy. Founded in America by pioneer Marian Chace, who spent years working in the then back wards of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, DC, with severely psychotic patients for whom standard treatments did not help, Marian Chace (Chace, Sandel, and Chaiklin, 1993) continued to develop her work with veterans returning from the Second World War, whom other mental health professionals found challenging to treat. The inability to speak the horrors of war the soldiers had experienced made typical treatment almost obsolete, so Marian also worked with them, through movement and other forms of artistic expression, to process their traumatic exposures. DMT defined by the American Dance Therapy Association (ADTA) is ‘Based on the empirically supported premise that the body, mind and spirit are interconnected’ and as ‘the psychotherapeutic use of movement to further the emotional, cognitive, physical and social integration of the individual’ (ADTA, 2016). DMT has grown in application, theory and more recently, neuro-scientific endorsement as a best practice (ADTA, 2016). DMT is a convergence of developmental psychology, somatic psychology and creative arts therapies because of its emphasis on movement as a primary language, and its unique ability to access the creative process through the continuum of breath-movement-dance that is an inherent part of human expression. DMT recognizes that our primary relationships are initially non-verbal (Lewis, 1986) and that memories and self-identity are linked: ‘Somatic material, unconscious material and conscious behaviour are stored in the body and are reflected in the breathing, posturing, and movement of an individual’ (Lewis, 1986).

DMT merits recognition as a best practice for trauma treatment. Unlike other somatic approaches to trauma treatment, DMT does not solely focus on somatic awareness and/or verbal processing of both resource and trauma experience. DMT’s developmental origins and capacity for working with an entire range of movement from simple breathing to creative expression offer clients a much bigger palette of options to move and heal from. DMT’s are well trained in assessment and diagnostic skills that range from non-verbal observation of muscle tonus, energetic sequencing of movement; basic neurological actions and effort states to complete verbal and cognitive processing. Given the nature of traumatic memory and the now well-established classification of traumatization as a body-based state of fear DMT is a powerful approach for establishing resources and processing traumatic memories, towards the pathway of integration for the client. While casework, which is beyond the scope of this chapter, is the most direct means to demonstrate this claim, DMT emphasizes movement as a primary language combined with the aforementioned growing body of knowledge about the relationship between movement, attention, and neuroplasticity (Begley, 2007, p. 159). Thus, research on trauma, the brain and memory, and the very physiological nature of the trauma reaction at the moment of exposure, all converge to support DMT as perhaps the most comprehensive body and movement-based therapeutic approach for the treatment of trauma. Trauma treatment is not just about processing memories but about integrating life-changing experience in a holistic and meaningful way. This can only be done with the full engagement of the body and its primary language of movement.

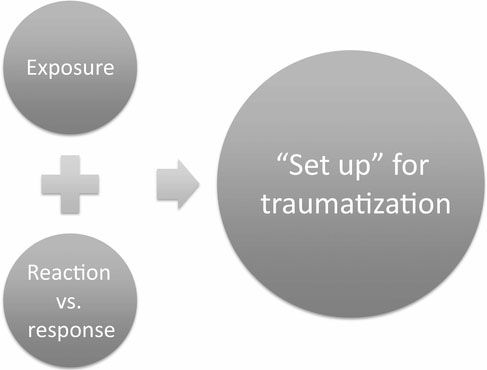

The exposure to a dangerous or life-threatening event creates a fear (danger) or terror (life threat) reaction, and it is this reaction that creates traumatization. While the body itself may not distinguish between types of exposure (i.e. motor vehicle accident vs. rape), our minds, which Antonio Damasio (2005) describes as a function of brain and body, help us create meaning and determine the influence of these events on our life experience. What is important to understand is that trauma is not the event itself, it is the reaction [vs. the ability to respond, or pause and plan (McGonigal, 2013)] to an exposure: i.e., the act of terrorism, the violent sabotage or rape; the verbal abuse throughout childhood, the explosion, etc., and the amount of support that ensues, or not, that sets up an individual for traumatization. The root of the emotional overwhelm that is often how this reaction is described and remembered, is physiological. Figure 12.2 shows this set up.

Traumatization, for the purpose of this chapter, is not solely limited to a clinical diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Traumatization occurs when the fear or terror one experiences in that moment of exposure remains in the body; because the hormonal, neurological, bio-chemical, and functional changes that occur (van der Kolk, 2014) have not reset or returned to baseline. This is why trauma is not something from which we recover fully; if we manage to remain responsive in the moment of exposure, and have the appropriate support to heal, we may not be traumatized. However, for many survivors whose response was based on fear or terror, and who do not have access to whatever support they need to heal, be it spiritual, psychological, familial, communal, or otherwise, traumatization is likely, and the traumatization is a fear-based physiological state that is embodied.

Figure 12.2 The trauma reaction

Recent years have seen increased theory and literature about types of trauma. Definitions range from primary and secondary trauma to intergenerational (Danieli, 1998) and historic trauma (Yellowhorse-Braveheart et al., 2011), betrayal trauma (Freyd, 2008), complex trauma (Courtois and Ford, 2013; Herman, 1992, 2015; Spinazzola et al., 2002), and more. An in-depth analysis of the types of trauma that are currently shared in the literature is beyond the scope of this chapter. Relational trauma, the subject of this chapter, has a unique complexity because relationship is so foundational to our humanity. From a developmental and a humanitarian perspective, safety precedes the trust that is essential to engage in meaningful relationship. When humans endure relational trauma, it can undermine the very basis of our humanity, of our sense of meaning and belonging. Relational trauma can be volitional or non-volitional, in terms of the relationship. Torture is a non-volitional relational trauma; domestic violence is volitional because the relationship is a chosen one. This is not to suggest that the abuse is volitional, rather that the relationship is volitional, which adds to the complexity of the traumatic experience and the suffering of the survivor.

Salter (1995) refines our understanding of relational trauma when she writes about the effect sadistic and non-sadistic abuse can have on victims; the very essence of sadistic abuse in the context of relational trauma is an exploitation of empathy. Ongoing research in, and theories about, mirror neurons and empathy (Buk, 2009; Iacoboni, 2009; Winters, 2008) contribute to our understanding that human beings are soft wired for empathy. It is something we are naturally inclined to develop (although not everyone does). Empathy is fundamental to our connection to other people. The exploitation of empathy by sadistic abusers adds to the complexity of the traumatization, and it is for these types of trauma that DMT is uniquely helpful.

DMT, like all good psychotherapies, utilizes empathy as a basis for our therapeutic rapport and connection to the client. Because of the inherently embodied nature of DMT, we may also be inclined in the direction of compassion, which is defined by Roshi Joan Halifax as ‘empathy with action’ (R. J. Halifax, personal communication, 2nd June, 2014). Tobey (H. Tobey, personal communication, 13th October, 2003) differentiates sympathy from empathy, and empathy from compassion, and this author describes her awareness of the potency of empathy not only to heal, but to disturb clients who suffered severe relational trauma (Gray, 2015b). Based on Tobey’s work and the author’s clinical experience, sympathy, which is defined as ‘feeling sorry for another person’ (Gray, 2015b, p. 32), is unhelpful in work with survivors of relational abuse because of the inherent power differential that has already undermined and distorted the basis of being human, and being in relationship, for that individual. Empowerment might always be a desired outcome of work with survivors of relational abuse.

Empathy is essential to the connection we feel for our clients and is essential in our embodied understanding of their clinical presentation. ‘I feel your pain’ (or, joy) might sum up an empathic response to a client’s story. Tania Singer and colleagues have done research that pinpoints the areas of the brain that are activated when experienced meditators respond to stories of suffering. Empathy to another’s suffering activates the pain related parts of the neural network associated with emotions but not sensorial experiences; it increases negative emotions (Singer, 2014, p. 1; Singer and Klimecki, 2013).

When these same experienced meditators practice compassion, which can be defined as the recognition of ones suffering or pain because I, or we, know my/our own and can see them as separate or unattached, the positive emotions increase and negative emotions decrease. We feel concern (not their pain), and feelings of love and warmth. It develops a strong motivation to help and lights up areas of the brain associated with reward, love and affiliation. This increases plasticity (Hanson and Mendius, 2009; Klimecki, Leiberg, Matthieu, and Singer, 2014; Singer, 2014).

Restorative Movement Psychotherapy (RMP) is the author’s adaption of dance/movement therapy specifically for therapy with survivors of relational trauma. This framework has been developed, and is developing, ongoing, based on the authors work with survivors of human rights abuses who are displaced by war, torture, genocide, and terrorism. This work has also been influenced and informed by work with survivors of ritual abuse, child abuse and in disasters and other humanitarian contexts. The premise of RMP is that belonging and meaning-making (which sit at the apex of the triangle in Figure 12.1) are the ultimate clinical outcomes for those affected by relational trauma. Our sense of belonging is core to our connection to others, because it is a refraction of our connection to our self in our world. Current theories from neuroplasticity (Cozolino, 2014; Siegel, 2012) demonstrate how the plasticity of the brain is enhanced in relationship. Siegel refers to this in his definition of the brain as ‘embodied and relational’ (Siegel, 2013). It is through belonging that we can begin to create meaning out of our life experiences.

Many of the evidence-based therapies show results in positive clinical outcomes for specific symptomology, but do not necessarily take a more global approach i.e. measure significant changes in client lives. Changes such as restoration of intimacy, creating meaning out of suffering, a sense of safety in relationship and reduced isolation, are important in terms of any of our humanity. These more global consequences are often overlooked in mainstream clinical approaches and programs. Survivors of relational trauma, especially those displaced by war and violence, experience a sense of displacement and a loss of safety. Whether the displacement is from one’s home country or land, or loss of a safe connection to one’s own body, our place in the world is impacted by the experience of relational trauma.

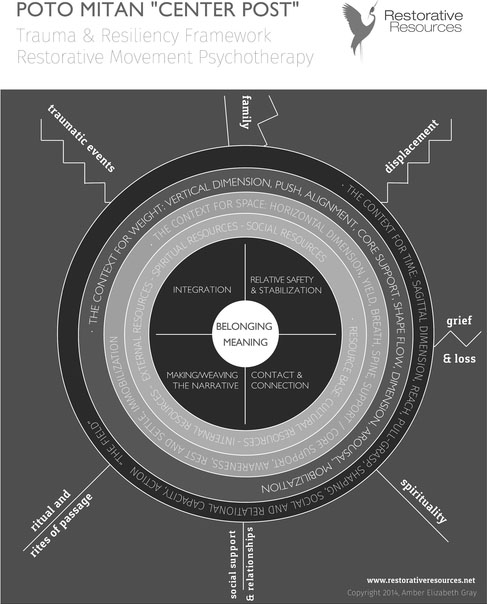

RMP is based on the ‘Poto Mitan’ Framework for Trauma and Resiliency (Gray, 2015a). Poto Mitan translates as Centerpost, but its meaning in Haitian Creole is closely akin to ‘The Center of All Things’. This name reflects the belief that for healing, or the restorative process, to occur one must return to one’s own center. In Haitian tradition, healing ceremonies are marked by a Poto Mitan – sometimes visible, sometimes invisible – around which the community gathers to drum, sing, dance, and connect to one another and to spirit. The name of this framework reflects several movement therapies, such as DMT, Somatic Psychology, and Continuum Movement all of which have a unique ability to address all aspects of our humanness, from the most mundane to the most sublime. DMT is the core psychotherapy of this framework.

In the center of Figure 12.3 is belonging and meaning (which sit at the apex of the revised CBT triangle of Figure 12.1) reflecting the ultimate clinical outcomes, achievable only through a holistic and comprehensive approach to psychotherapy, in which DMT is uniquely positioned to provide. While amelioration of symptoms such as PTSD, depression, anxiety are important and hoped for outcomes of good therapy (often cited in evidence-based research), this research rarely offers insight into more global outcomes that may have meaning to the clients themselves, especially clients who come from more community or socio-centric cultures. The profoundly disruptive and heart-breaking experience of displacement, which may be the most defining feature of the refugee experience, by definition undermines our birthright sense of belonging and all that gives meaning to life. The arts, in all its forms, have a longer history as a source for healing, mourning, celebrating and marking life’s passages than psychology or medicine.

The concentric circles placed out from the center illustrate RMP, a DMT-based approach to working with relational trauma across cultures. Its components-based format allows for the balance in structure, flexibility and adaptation that cross-cultural psychotherapy warrants. The concentric circles that surround the center progress outwardly and illustrate the components of the framework.

Closest to the center is a circle that illustrates the phases of this treatment approach. Complex trauma, a term coined originally by Herman (1992; 2015) and now endorsed and researched by many of the primary contributors to the field of traumatic stress research (Courtois and Ford, 2013; Spinazzola et al., 2002) was proposed as an alternative diagnosis to PTSD for the DSM-IV. While complex trauma did not become a diagnosis, theories, and research arising from the recognition that adult survivors of long-term child abuse and extreme interpersonal trauma, like torture and ritual abuse, who often present with significantly more chronic and complex symptomology, has made an impact on trauma treatment. For complex trauma, a phasic approach is the gold standard. While every theorist has their own interpretation of these phases, all of them begin with Safety and Stabilization.

Figure 12.3 The Poto Mitan framework for trauma and resiliency

Relative Safety and Stabilization in this framework is therefore Phase 1, which describes the role of safety in any healing process. It has perhaps received the most current endorsement from Polyvagal Theory as crucial to psychological safety (Porges, 2011). Polyvagal-informed DMT and Polyvagal-informed Continuum Movement (CM) are subjects of several recent chapters (Gray, 2015a, c, 2018; Gray and Porges, 2017). The polyvagal theory emphasizes two neural circuits (ventral, or smart vagus and dorsal, or old vagus), and three responsive pathways (social engagement, mobilization, and immobilization) arising from five states: a) safety, which promotes social engagement; b) mobilization with fear; c) mobilization without fear; d) immobilization with fear; and e) immobilization without fear (Gray, 2018; Gray and Porges, 2017; Porges, 2011).

The fear-based states arise when our survival circuits are recruited, because we face danger (mobilization with fear, often known as fight or flight) or life threat (immobilization with fear/ terror or shut down). In order to remain or promote a state of social engagement, safety is necessary. Safety, long appreciated as the base of Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs” (1943, p. 376) is now demonstrated through current research as a physiological state that promotes our emotional and psychological sense of safety, and therefore ability to engage with the world.

St. Just (personal communication, 13th October, 2000) coined the term ‘relative safety’ to illuminate the reality that the world is never truly safe, and we are perhaps best described as being just safe enough. For survivors still living in violence, or for those so traumatized that their suffering is perpetual, relative safety is a more apt term. To suggest complete safety can be a set up. This is particularly true in any context where survivors are still at risk of exposure to traumatic events, for example, domestic violence, civil conflict, war, high-risk jobs, etc. Even for those survivors who are living in safe environments, until they can actually experience a sense of safety, even the smallest environmental cue can trigger a sense of danger. In this approach, relative safety and stabilization are embodied; RMP is one of the first body-based approaches to emphasize simple structured processes for stabilization that shift states effectively during both early phases in therapy, in resourcing work, or the traumatic processing that occurs when clients are adequately prepared to recall and process their traumatic histories. Psychological First Aid (2006) emphasizes stabilization early in the process and it is this author’s clinical observation that establishing relative safety and stabilization is simultaneously the place we begin with new clients to build trust and rapport and is ongoing through the entire course of a patient’s restorative process. Psychosocial education in this context is the normalizing trauma responses and assisting clients to understand the biological and physiologic basis of the stress response, or the basic frameworks of our theoretical foundations and clinical approaches. This together with resourcing are considered fundamental components of Relative Safety and Stabilization (Phase 1) in complex trauma treatment.

The remaining three phases vary from other phasic approaches to complex trauma. Many approaches to complex trauma follow Herman’s (2015) framework, where Phase 2 is processing grief, loss and trauma, and Phase 3 is reconnection. Contact and Connection, described as Phase 2, proposes that prior to processing one’s trauma history, making contact and connecting to one’s own sense of self, broadly defined for socio-centric cultures that may include others, ancestors and even planets in sense of self, is essential. Contact and Connection are relational, and relationship is widely understood to heal, whether through the enhancement of neuroplasticity (Cozolino, 2014; Siegel, 2013, 2014) or through the comfort of togetherness. In Phase 2, therapists assist clients to connect to all levels of human experience: sensation and sensorimotoric information, perception, impulse to move and movement, the continuum of affect, and thoughts, cognitions, and beliefs (see Figure 12.3). Mystery, a more transpersonal perspective, is uniquely at both the base (source) and top (self-actualization) because DMT acknowledges all levels and dimensions of human experience, from physical to spiritual (ADTA, 2016). In the moment of exposure, the loss of safety that occurs spurs dissolution from our usual social engaged behaviors and interactions to behaviors arising from survival circuits. This dissolution can truncate the sequencing of energy that connects us through these various layers or levels of our humanness.

Weaving the Narrative is the Meaning-Making Phase 3 of therapy; this is when memories are processed. The establishment, through therapy, of relative safety, restoration and connection in self, and of self with other over time, provides the ground for this processing to occur and is also part of the processing. The restoration of these connections co-occurring with the establishment of resources, to increase relative safety and mastery of one’s physiological or bodily responses (stabilization) prepares the client for the processing of trauma and loss. The strength of RMP for processing traumatic memory is the constant looping into the somatic or bodily experience of the memories, and exploration and sequencing to completion of sensations, micromovements and movements arising from the moment of exposure to physiological reactivity. Processing of trauma memories is bilateral and bi-directional in that we constantly connect thoughts and emotions to the sensations of the body, top down and bottom up, and we loop resource and trauma memories and experiences together to weave these experiences into the broader context of life experience and the client’s entire life-line. It is referred to as the River of Life in this framework, which acknowledges the fluid nature of memory, in all circumstances, and especially for survivors of trauma whose time-space orientation has been altered.

Integration is the final Phase 4, and refers to a multi-dimensional integration: the integration of the brain (Siegel, 2013), referring to both old and new, or ‘upstairs downstairs’ (Siegel, 2012) and left and right brain and its ability to restore a narrative; the reduction of limbic reactivity when potential triggers present; the placement of traumatic experience in the context of one’s life history; an ability to maintain mindfully present states and a sense of future, vs. being eternally stuck in the imprints of the past. In more practical terms, integration is the ability to take the change that occurs in therapy, the new neural pathways that movement is particularly beneficial for inspiring and incorporate them into one’s daily life. Movement is what carves and creates new neural pathways (Perry, 2017); rest and settle, or sleep, states cement them into our mind, or consciousness.

These phases are not linear; like the rest of the framework that illustrates RMP, these phases are reference points for the restorative process. Early in therapy, we may focus almost exclusively on restoring relative safety and stability and fostering connection. As the restorative process continues, we weave all four phases together to process the aspects of clients’ traumatic past with growing resources towards integration so that one can be present to participate and engage with life in the present moment.

The primary and secondary portals to embodiment are pathways for these components to guide the restorative process. Simply stated, these are pathways that this author has observed are accessible to survivors of trauma in many different contexts. A mission of this framework is accessibility; many survivors of trauma remain in contexts where they cannot access any form of therapy or would not usually participate in psychotherapy due to cultural and spiritual beliefs that may offer other forms of healing as the norm. Stigmas about psychology and mental illness can make all mental health approaches less accessible in many settings. With the number of displaced peoples around the world at an all-time high (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2014) the need for straightforward approaches to any therapeutic process is essential. The use of this framework in an international humanitarian context merits its own chapter; for the purposes of this chapter, this framework has been developed through applied practice in United States-based clinics offering services to refugees and survivors of torture, as well as active conflict zones, complex humanitarian emergencies, and post-disaster contexts. The portals provide a direct pathway to somatic awareness (Hindi, 2012) a term which this author describes as combining embodied awareness (the feeling of experience, and our ability to interocept, or connect to our inner landscape) and conceptual awareness, which is our ability to describe, think about, evaluate or talk about inner experience.

Breath, spine, and weight are the primary portals to the embodiment in this framework, and space, time and rhythmicity are the secondary portals. Breath is a core influence on movement in Bartenieff Fundamentals because ‘Movement rides on the flow of the breath’ (Bartenieff and Lewis, 1980, p. 232). Breath is a well-known phenomenon around the world. From the very practical and necessary, autonomic act of breathing, to the more sublime and esoteric interpretations of the meaning of breath in many ancient traditions (such as Kundalini yoga) and more current breath-based practices [i.e. Holotropic Breath work (Grof and Grof, 2010)]; breath is a concept and an action that is globally understood. In many languages, breath and spirit are the same word (Prana in Hindi, Chi in Chinese, Pneuma in Greek). Breath is literally and metaphorically the wave we all ride into life, and ride out, when we die; it is the veil between worlds. As subtle as breath-based practices can seem, breath shifts our physiological state, which regulates our nervous system, faster than anything else (S. W. Porges, personal communication, 2nd October, 2008).

Many somatic therapies under-privilege the spine, which tends to remain in the domain of yogic movement practices and bodywork, such as osteopathy and chiropractic medicine. The spine is literally the backside of our mid-line. In fact, the physically invisible but ever-present mid-line, around which each body organizes in utero, together with the spine, is the physical embodiment of the Poto Mitan in this framework. In many ancient cultures and traditions, the spine was considered to be the axis mundi of our body, connecting us to heaven and earth. The spine is often considered only for its palpable presence in the very back of the body; the spine, as a structure, is enervated by all the major nerve systems in the body. The spinal cord is protected by the vertebral column known as the spine, and the front of the spine connects to respiration via the diaphragm, at T-12. Dance/movement therapy offers unique and well-developed theories about the role of the spine, and the sacrum, in maintaining physical and mental health. Blanche Evan and Liljan Espenak’s pioneering work as founders of DMT includes theories, systems of assessment and intervention, and practices that focus on the spine as core to well-being. Evan (1992) considered the physiological health of the spine reflective of psychological health, and Espenak (2005) assessed client well-being through the wheel-like motion of the sacrum, at the base of the spine. Cottingham et al. (1988, p. 353) demonstrate the shifts in pelvic tilt can shift and promote vagal tone, which is one measure of a state of physiological health necessary to promote social engagement. Hindi (2012) describes the spine as a pathway for interoception; a ‘corridor a corridor for sensory information to travel to the brain, making a pathway for unconscious interoceptive data to be brought into consciousness and processed’ (2012, p. 135). More simply, this author has never encountered a person in any country or context that did not know what and where the spine is and did not have some relationship to its relevance to embodiment and to well-being.

Weight, which is the physical evidence of our presence, can seem more abstract to locate. However, a simple formula of finding points of physical contact between whatever surface one is lying, sitting or standing on, and the body, and sensing how much support is received, or not, through these points of contact, invites clients into a sense of their weight. It is also, of course, a measure of the ability to receive support, which relates to yield (Bainbridge Cohen, 2012). The LMA Effort states use weight, expressed on a continuum from strong to light, to assess effort in movement and action. Many survivors of relational trauma describe feeling very ‘heavy’, i.e. too weighted down, by the burdens of suffering they carry, or by sadness of loss. Likewise, ‘lightness’ has been associated with feeling empty in both positive and negative ways; it can also denote dissociative states. At times, a shift from heavy to more levity signals a restoration of embodiment; the reverse is true when one exists in chronic shut-down states, which are often expressed psychologically as dissociation. These shifts in sense of weight are cues that physiological state shifts have occurred; physiological state shifts are the foundation of emotional and psychological state shifts.

The secondary portals to embodiment are so named because they tend to be processes that, while present in early phases of therapy, are usually more complex and more accessible to focus on later in treatment. Space is in the first concentric circle of the developmental process, and might be considered one of our earliest relationships, as we are in relationship to space in utero, and in the developmentally early horizontal dimension. Space, which in LMA is an effort that relates to our thinking and perceptual abilities and tendencies, is also literally that which we relate to through movement. We move through space. It is this therapist’s observation over many years that many survivors of relational trauma whose exposure includes captivity (whether physical or psychological, such as being followed) have an altered and often very uncomfortable relationship to space. For some, it is simply terrifying to be in relationship to space. The kinesphere, our personal space bubble reflects our relationship to space and the environment around us. Konie (2011, p. 5) describing kinesphere from the perspective of Bartenieff Fundamentals, states the kinesphere is: ‘The 3-Dimensional volume of space that I can access with my body without shifting my weight to change my stance. (Psychological Kinesphere: The space I can – attend to.)’. Many survivors’ initial clinical presentation is one of a retracted kinesphere, as the case study describes. This complex relationship to kinespheric space, the space around us, and inner or interoceptive space in a body that can feel like a minefield, makes it difficult to work directly and intensively with space early in treatment.

Time is a dimension from LMA framework that we naturally explore later in life. Time and space orientation, by definition, are absent in states of dissociation, quite common to survivors of extreme interpersonal violence, and in physiological shut down or immobilized states. Our movement in time is related to the sagittal dimension and our ability to interact with the environment, based on our appraisal of the safety, or lack of, in the environment (or space around us). Traumatized individuals by definition perceive the world as unsafe; their nervous systems have shifted into states of chronic fear or terror and they continuously mis-appraise the environment as unsafe even when it practically speaking is safe. Our relationship to time, in this framework for the restorative process, reflects our ability to move towards what we choose, or want, in our own timing, and move away or withdraw from that which we do not wish to engage. This ability is undermined by the fear that is core to the experience of being traumatized. Because the time dimensions are relational, it is often relatively safer for clients to begin in the vertical dimension of the preceding circle although out of sequence developmentally. This promotes mindful re-establishment of boundaries and allows defenses to deconstruct. If clients can mobilize and slowly re-engage in more active play states with less and less fear present, they can regain enough comfort to begin to re-engage with the world. Relationships are fundamental to our humanity, and the perverse abuse of the power differential in relational trauma can make relationship scary. One’s sense of self, as experienced through the present moment experience of weight, may need to be the first portal to embodiment restored before one can find the trust (yield) to interocept and rest and relax. Relating outwardly to the world rests on this foundation of space/trust/yield/ horizontal, and weight/mobilize/push/vertical.

Rhythmicity is core to polyvagal-informed DMT and CM. The entire approach is based on coherence in internal, or endogenous, and external or exogenous, biorhythms. Sadistic abusers, as described in the preceding section on relational trauma, will intentionally increase suffering for their own vicarious pleasure. This intentional abuse often purposefully resets important biorhythms, such as digestion and elimination, respiration, heart rate, etc. This intentional mis-wiring of these core-to-well-being rhythms literally cause us to ‘lose our beat’, which has profound effects on our external rhythmicity, i.e. how we move in the world. Rhythm and rhythmicity is worthy of an entire book, and is the focus of a chapter on polyvagal-informed DMT and CM (Gray, 2018). For the purposes of this chapter rhythmic feedback loops are fundamental and core to our internal physiological states and external, fluid movement, actions, and engagement with the world, and are the essence of rhythmicity as a secondary portal. Rhythmicity might be seen as the most integrative of the portals, because when we can align our internal and external realities and rhythms, we can move to our natural beat again.

The arts have been the voice of suffering, celebration, mourning, ritual, and rites of passage, far longer than medicine or psychology. Because traumatic experiences and exposures are a daily global occurrence, people and communities in all countries and cultures benefit from and deserve novel and informed approaches that build on tradition and what has worked historically to heal the wounds of violence and abuse. The embodied and creative nature of DMT and RMP makes trauma-informed applications of this work more accessible for survivors of trauma in a variety of contexts, and may offer a relevance to their restorative process that other approaches do not.

American Dance Therapy Association (ADTA). (2016). FAQs. Retrieved from https://adta.org/faqs/.

American Dance Therapy Association. Retrieved from https://adta.org/.

Bainbridge Cohen, B. (2012). Sensing, Feeling and Action: The Experiential Anatomy of Body-Mind Centering. Toronto: Contact Editions.

Bartenieff, I., and Lewis, D. (1980). Body Movement; Coping with the Environment. New York: Gordon and Breach.

Begley, S., (2007). Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain: How a New Science Reveals Our Extraordinary Potential to Transform Ourselves. New York: Ballantine Books.

Buk, A. (2009). The mirror neuron system and embodied simulation: Clinical implications for art therapists working with trauma survivors. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 36, 61–74. (Original work published 1988)

Chace, M., Sandel, S., and Chaiklin, S. (1993). Foundations of Dance Movement Therapy: The Life and Works of Marian Chace. Columbia, MD: American Dance Therapy Association.

Cottingham, J., Porges, S., and Lyon, T. (1988). Effects of soft tissue mobilization on parasympathetic tone in two age groups. Physical Therapy, 68, 352–356.

Courtois, C. A., and Ford, J. D. (2013). Treatment of Complex Trauma: A Sequenced, Relationship-based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

Cozolino (2013). The Social Neuroscience of Education: Optimizing Attachment and Learning in the Classroom. New York: Norton.

Cozolino, L. (2014). Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology: The Neuroscience of Human Relationships: Attachment and the Developing Social Brain (2nd ed.). New York: Norton Books.

Damasio, A. (2005). Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. London: Penguin Books.

Danieli, Y. (1998). International Handbook of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma. New York: Plenum Press .

Espenak, L. (2005). Psychomotor therapy with a varied population. In F. Levy (Ed.), Dance/Movement Therapy: A Healing Art. (Chapter 3). 2nd Revised Edition. Virginia, USA: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance.

Evan, B. (1992). Creative movement becomes dance therapy with normal and neurotics. In F. Levy (Ed.), Dance/Movement Therapy: A Healing Art. (Chapter 2). 2nd Revised Edition. Virginia, USA: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance.

Freyd, J. (2008). Retrieved from http://dynamic.uoregon.edu/jjf/defineBT.html.

Gray, A. E. (2015a). The broken body: Somatic perspectives on surviving torture. In S. L. Brooke and C. E. Myers (Eds.), Therapists Creating a Cultural Tapestry: Using the Creative Therapies across Cultures (pp. 170–190). Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Gray, A. E. (2015b). What language does your body speak: Some thoughts on somatic psychotherapies in international contexts. Somatic Psychotherapy Today, 5(4), 30–37.

Gray, A. E. (2015c). Dance/movement therapy with refugee and survivor children: A healing pathway is a creative process. In C. Malchiodi (Ed.), Creative Interventions with Traumatized Children (2nd ed., pp. 169–190). New York: Guilford Press.

Gray, A. E. (2018). Roots, Rhythm, Reciprocity: Polyvagal Informed Dance Movement Therapy for Survivors of Trauma. In S. W. Porges and D. Dana (Eds.), Clinical Applications of the Polyvagal Theory: The Emergence of Polyvagal-Informed Therapies (pp. 207–226). New York: Norton Books.

Gray, A. E., and Porges, S. (2017). Polyvagal-informed dance movement therapy. In C. Malchiodi and D. Crenshaw (Eds.), What To Do when Children Clam Up in Psychotherapy: Interventions to Facilitate Communication (pp. 102–136). New York: Guilford Press.

Grof, S., and Grof, C. (2010). Holotropic Breathwork: A New Approach to Self-Exploration and Therapy. New York: Excelsior Editions.

Halifax, R. J. (2014.) Personal communication, 2nd June 2014.

Hanson, R., and Mendius, R. (2009). Buddha’s Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love and Wisdom. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377–391. Retrieved May 2017 from http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.emils.lib.colum.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=0b54d06f7a24-46af-a168-bbdd747191a3%40sessionmgr4001andvid=11andhid=4110.

Herman, J. L. (2015). Trauma and Recovery. New York: Basic Books.

Hindi, F. S. (2012). How attention to interoception can inform dance/movement therapy. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 34(2), 129–140. doi:10.1007/s10465-012-9136-8

Iacoboni, M. (2009). Imitation, empathy and mirror neurons. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 653–670. Retrieved from arjournals.annualreviews.org.

Klimecki, O. M., Leiberg, S., Matthieu, R., and Singer, T. (2014). Differential pattern of functional brain plasticity after compassion and empathy training. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience Advances, 9, 873–879.

Konie, R. (2011). A Brief Overview of LABAN MOVEMENT ANALYSIS. Retrieved March 2017 from www.movementhasmeaning.com.

Lewis, P. (1986). Theoretical Approaches in Dance Movement Therapy (Vol. 1). Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396.

McGonigal, K. (2013). The Neurobiology of Willpower: It’s not What You’d Expect. Storrs, CT: National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine.

Perry, B. D. (2017). The Moving Child: Supporting Early Development through Movement [Film]. Vancouver, BC, Canada. Retrieved from www.themovingchild.com.

Porges, S. W. (2008). Personal communication, 2nd October 2008.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, Self-Regulation. New York: W.W. Norton.

Psychological First Aid. (2006). Field Operations Guide (2nd ed.). Retrieved March 2010 from www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/manuals/psych-first-aid.asp.

Salter, A. (1995). Transforming Trauma: A Guide to Understanding and Treating Adult Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Siegel, D. (2012). Bringing out the best in kids: Strategies for working with the developing mind. A webinar session. The National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine. Retrieved from www.nicabm.com.

Siegel, D. (2013). The mind lives in two places: Inside your body, embedded in the world. A webinar session. The National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine. Retrieved from www.nicabm.com.

Siegel, D. (2014). Mind: A Journey to the Heart of Being Human. (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Singer, T. (2014). Feeling Others’ Pain: Transforming Empathy into Compassion. Retrieved from www.cogneurosociety.org/empathy_pain/.

Singer, T., and Klimecki, O. M. (2013). Empathy and compassion. Current Biology, 24 (18), R875–R878.

Spinazzola, J., Ford, J., van der Kolk, B., Blaustein, M., Brymer, M., Gardner, L.,. . . Smith, S. (2002). Complex Trauma in the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Retrieved May 2017 from www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/assets/pdfs/Complex_TraumaintheNCTSN.pdf.

St. Just (2000). Personal communication, 13th October 2000.

Tobey, H. (2003). Personal communication, 13th October 2003.

UNHCR. (2014, June 20). Annual Global Trends. News Stories.

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. New York: Viking.

Winters, A. (2008). Emotion, embodiment and mirror neurons in dance movement therapy: A connection across disciplines. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 30, 84–105.

Yellowhorse-Braveheart, M., Chase, J., Elkins, J. and. Altschul, D. B. (2011) Historical trauma among indigenous peoples of the Americas: Concepts, research, and clinical considerations, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43(4), 282–290, DOI: 10.1080/02791072.2011.628913