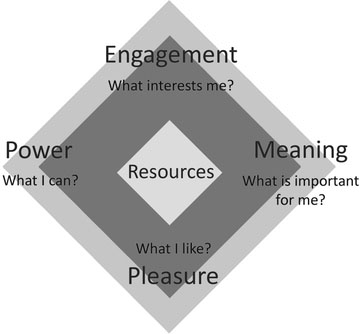

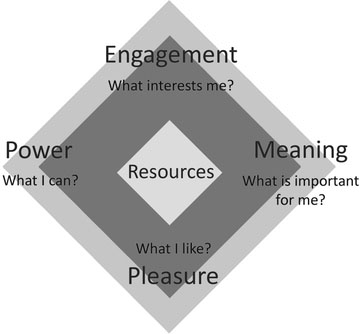

Figure 14.1 Engagement, power, meaning, pleasure

Alexander Girshon and Ekaterina Karatygina

The concept of personal and psychological resources is common in various areas of social work and psychotherapy. Some studies show that a marked improvement in the realisation of personal resources during psychotherapy can show significant correlations to the improvement of symptoms in clinical setting (Kati, Stumpf, Heuft, Burgmer, and Schneider, 2015). At the same time, the definition of resources varies from therapist to therapist. It seems that there is no clear and distinct picture of what resources actually are, and how and where to look for them. We would like to propose a model of resources, which is based on an integral approach, positive psychology and dance movement therapy practice.

Our model of resources is inspired by the integral approach of the contemporary philosopher Wilber (2000, 2003). The intention of integral approach is to place a wide diversity of theories and thinkers into one single framework. It is portrayed as a ‘theory of everything’ (‘the living Totality of matter, body, mind, soul, and spirit’), trying ‘to draw together an already existing number of separate paradigms into an interrelated network of approaches that are mutually enriching’ (Wilber, 2003, p. xii).

Within this approach, we can connect the modern understanding of physiology and neuroscience with findings in somatic techniques; a dance movement therapy approach with the theoretical frame of transpersonal psychology, contemporary performance techniques and contact improvisation, mindfulness practices and ecstatic meditation, depending on the requirements, needs and abilities of clients and groups. This approach is used successfully in Russia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus, and Israel in work with children with special needs, in mental health clinics, in private practices, and in creative and personal development training. When practicing dance movement therapy in a training course or in individual therapy, we often turn to the concept of a resource. The basic principle here is: before you tackle a problem, check the availability of resources.

The term ‘resources’ is primarily associated with economics and geology. This could be because in Soviet Russia children often heard about ‘our native resources’, as Russia is reliant on its natural resource economy. These associations imply that resources are something deeply hidden, difficult to extract, and exhaustible. Other sources mention that resources are finite, can be easily wasted, and that it is important to manage them well. We are interested in the alluring beauty of the English etymology of this word – ‘re-source’, i.e. ‘return to the source’, or more precisely, ‘recover the source’. This is something fluid and free: resource as a process. These are resources that we can continuously replenish. So what resources can we recover and replenish in dance movement therapy?

To understand resources in the context of psychotherapy and personal development, we can turn to Ken Wilber’s integral approach which utilises three main perspectives: objective (material, third person resources, it/this), subjective (inner resources of the individual itself, first person resources, I), and intersubjective (resource relationships and communities, second person re-sources, We or I–You resources). In this article, the main focus will be on the first person resources, but we will also address the other two areas. We will start with safety as a prerequisite and key resource for therapy.

Safety, which engenders confidence, is one of the key factors in therapy. It is provided by boundaries, contract, and by the therapeutic setting overall. It is important to understand that real safety and a sense of safety may not be one and the same. In situations of trauma and stress our bodies and our unconscious do not perceive the world as a safe place. So how do our bodies and our unconscious react to trauma? We get an answer from the polyvagal perspective developed by Porges (2001). According to the polyvagal theory, the well-documented phylogenetic shift in neural regulation of the autonomic nervous system passes through three global stages, each with an associated behavioural strategy. The first stage is characterised by a primitive unmyelinated visceral vagus that fosters digestion and responds to threat by depressing metabolic activity. Behaviourally, the first stage is associated with immobilisation behaviours. The second stage is characterised by the sympathetic nervous system that is capable of increasing metabolic output and inhibiting the visceral vagus to foster mobilisation behaviours necessary for ‘fight or flight’. The third stage, unique to mammals, is characterised by a myelinated vagus that can rapidly regulate cardiac output to foster engagement and disengagement with the environment. The mammalian vagus is neuroanatomically linked to the cranial nerves that regulate social engagement via facial expression and vocalisation (Porges, 1995, 2001).

Thus, it is important to supplement the usual triad of the fight-flight-freeze stress responses with a newer component that Zoe Lodrick called ‘friend’. Friend is the earliest defensive strategy available to us ontogenetically and the last one developed phylogenetically (Lodrick, 2007). At birth the human infant’s amygdala is operational (Cozolino, 2002), and they utilise their cry in order to bring a caregiver to them. The non-mobile baby has to rely upon calling a protector to its aid, in the same way that the terrified adult screams in the hope that rescue will come. Once mobile the child may move towards another for protection, and with language comes the potential to negotiate, plead, or bribe one’s way out of danger. Throughout life when fearful most humans will activate their social engagement system (Porges, 1995).

Thus restoring safe communication in a stressful situation is an evolutionarily more recent, more complex and a more fragile coping strategy. To take the client out of their sense of unsafety, the polyvagal theory advises talking to the person quietly and gently, to lower the timbre of our voice in order to engage the person’s listening mechanism. This would provide the client with a calm environment without any loud extraneous sounds and noises.

It is also important to gather physical safety resources such as posture, movement, and position in space that are associated with an experience or memory of a safe environment and to share them with the therapist or group. In this sense, the experience of safety is a renewable and manageable resource.

These techniques have been used when working with people living near the Ukraine military conflict area. Verbal and rational methods could not adequately assist people who expected their homes to turn into a war zone at any moment in coping with their heightened anxiety. But physical exercises and mutual physical support helped reduce anxiety and led to open discussion about their anxieties and their options for action.

Much has been written about inner resources. Concepts such as motivation, intuition, discipline, stress resistance, etc., are all included in this category. The multifaceted term ‘energy’ is often used to refer to the basic level of activity and good mood. We consider three important concepts: power, pleasure, and meaning. These correspond to research in positive psychology. In well-being theory by Seligman (2011) there are five measurable elements:

No one element defines well-being, but each contributes to it. Some aspects of these five elements are measured subjectively by self-report, but other aspects are measured objectively. When comparing these models, we see that Positive emotions correlate with Pleasure, Accomplishment – with Power – and Meaning is Meaning. And, in line positive psychology research, we can add to this Engagement. Relationships correspond to second-person resources in our model. Thus, we get a clear and simple checklist of resources that we can test:

We can answer the question: What brings me satisfaction? Are there enough events and things in my life that bring pleasure (but do not cause damage)? How often do I feel comfortable, nice, or cool? How often do I find pleasure in the simple joys of life?

We do not need super-efforts to obtain the basic enjoyment from life (there are, of course, clinical exceptions). Our body is adapted for pleasure, and the internal reward system is constantly running; we just need to not interfere with the natural process and find ways to work with and be in balance with it.

In this context, we would like to share a parable about a Zen master. Students gathered at his deathbed to get the last instructions, many hoped for some wise saying about the Dharma. ‘Master, tell us!’ – a senior student asked. The old man opened his eyes and said: ‘Do you hear squirrels rustling on the roof? How lovely!’ And he died.

We can start a workshop by asking participants to perform the most pleasant and comfortable movement. Could you find one right now? It could be stretching, or a deep inhale and a relaxed exhale, a shake, or a jump – any movement that feels natural and brings you pleasure.

Dance movement therapy provides a wide variety of tools to obtain not only ‘simple’, but also ‘complex’ enjoyment from life. Those which relate to satisfaction of social, spiritual, or self-affirmation needs for example. So first, the very nature of dance movement therapy gives us the opportunity to develop complex movements that bring special pleasure to mind and body. And then the various sophisticated methods used within the approach, such as improvisation and performance, contact improvisation, authentic movement and etc., provide multi-faceted opportunities for learning how to take pleasure in ‘complex’ aspects of life. In completion, this unique, compound pleasure can be assimilated in all languages of consciousness and shared with other people. It would be difficult to overestimate these possibilities for modern culture.

When working with ‘pleasure’, the important issue of ‘sufficiency’ comes up. How much do I really need to get pleasure from something? What makes my pleasure ‘pure’, in general, and useful as a resource? How do I choose the ratio of quality and quantity of what brings me pleasure? I (Ekaterina Karatygina) remember how, in an Integral Somatic lesson by Alexander Girshon, while working with the senses we explored ‘taste’. After breaking off a piece of dark chocolate and slowly putting it in our mouths, each of us carefully scrutinised our feelings and emotions. Shades of flavour, its shape, the temperature, changing on contact with the tongue, observation of how the chocolate is melting and gradually coated the inside of the mouth, dripping down the throat into the oesophagus, – all of that mattered and unexpectedly brought a lot of joy to me. And it was just one small piece. Active and consciously sustained attention, sharing this unique pleasure with others, as well as the intellectual background of what was happening, were helping me greatly. This made a lot of sense. Pleasure backed by the meaning – which we will address later – is a special pleasure.

What do I find interesting? What captivates and fascinates me? Things can be interesting even without any direct practical benefit – but sometimes because of a practical benefit. As children, we have many different hobbies: I (Alexander Girshon) was engaged in aeromodelling, was soldering schemes of some strange devices with friends, attended a photography club and even briefly karate and other activities. But more than anything I loved reading. I read for hours, sometimes skipping school, forgetting homework and everything else. My father had collected a good library at home, so I could always dive into it. I think we all have an experience of a healthy immersion into feelings, into the flow of experience, being swept along on a wave of interest. This can happen in work or in relationships. It happens when I dance, when the movement itself, the music, or my internal and external environment take total control of me and lead me entirely.

When did you last experience this feeling of engagement, of moving with the stream? What helps you get in there and return safely? In dance and movement, it is quite easy for us to get into the flow of engagement. Music, rhythm, working with partners, and a group pattern of motion – all that can bring not only pleasure, but engage us as well. In developmental lessons and therapy sessions, a good question to ask is: In what way, and with what quality of motion would you be most interested in dancing right now? We can also work on developing the sensitivity of different sense organs.

There are two types of questions which are relevant:

Example 1 (Alexander Girshon): My favourite form of dance is a contact improvisation. We share weight within this form, so in the flow of movement supports come naturally, and it can be that my partner is on my back or shoulders, or vice versa. Largely due to the fact that, to me, support in dance is associated with the ‘I can’ feeling, it has always been easier for me to take my partner’s full weight, than for me to let them take all of mine. When I teach students how to take a partner’s weight safely and effectively, I see the same ‘I can’ excitement and pleasure. This feeling is easy to reach if we carefully measure the steps of development and the individual’s ability.

Example 2 (Alexander Girshon): One of the most exotic forms of dance I work with, is a dance in the water. We sometimes use this dance during our travel training sessions in warm countries. It is no secret that many people have a fear of diving. Usually this is linked to a bad swimming experience in childhood or trauma. It is not a fear that hinders us in our daily life: people can swim well with it but lowering their face into the water creates an unpleasant experience. And this can be an obstacle for underwater dance training. One of the participants during a training trip to Thailand 2 years ago wanted to overcome this fear. We carefully divided her dives into small steps and actions she could take. We took as many steps as was necessary and worked with as much energy and aspiration as was possible. Two years later, she participated in a somatic water dance laboratory, performing various complicated and disorienting movements under water, in the sea and in a swimming pool. As she said, this experience didn’t only give her the freedom to swim and dance underwater, but also taught her to deal with complex and frightening tasks in her life.

Where and when do you have the ‘I can’ feeling? What actions and abilities is it connected with? Can you organise a number of practices where this experience of yourself can be strengthened until it could be reasonably transferred into other areas of your life?

We believe that ‘power’ is one of the key resources (along with ‘meaning’) that we need both to meet our needs and to solve problems, and also to help us survive and cope with dangerous and stressful situations. When we work with ‘power’ in the context of traumatic experiences, the session may include a ‘moving forward’, but also an ‘escape’, not only an ‘expression of anger’, but also ‘managing’ it, and not only ‘action’, but also ‘inaction’. It is necessary to make a deliberate choice of the optimal strategy, regardless of how it is ‘generally accepted’ in the social system, which usually exerts a strong pressure on our understanding of ‘power’ and ‘weakness’.

What is important to me? Are there any activities, events, projects, or people in my life that are truly and deeply important to me? Meaning is a special and hard to define category of human experience. There are different perspectives of interpreting meaning. Idealistic – when meaning is a special idea, with its own existence and status, different from ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ (Plato, Frege, 1979). Systemic – when meaning is the role that an action or event plays in the context of the whole. Analytical-pragmatic – when meaning is a utility or utilisation (‘Meaning-is-use’, Wittgenstein, 2001, p. 14). Existential – when meaning is what a person creates. Empirical – which views meaning as an experience (‘felt-sense’, Gendlin, 1996, p. 26). The abundance of perspectives may indicate that meaning is one of the keys for understanding human nature.

In a practical, therapeutic context, it is important to consider the concept of ‘sensed’ or ‘experienced’ meaning and the connection of the meaning and values embodied in a person’s life. I (Alexander Girshon) have one perspective example: my personal value of ‘freedom’ is embodied in the fact that I am self-employed (no outside control), in my passion for travel (freedom of movement), or in a choice of improvisational dance forms (freedom of motion), etc. I (Ekaterina Karatygina) have another perspective example: my personal binary value of ‘synthesis and uniqueness’ is embodied in the fact that in my various work fields (art, psychology, and business) I like to combine very different types of art, developmental, or healing techniques and methods, depending on the ‘needs and senses of the moment’.

When was the last time you experienced the feeling of a moment’s significance? What action, environment, or quality of existence caused that feeling? When we see and feel that the special space of dance and the beauty of emotions experienced in a group, a pair or an individual dance appear, we call it a ‘moment of grace’. This feeling is difficult to describe, and impossible to retain, but it is this quality of presence and feeling that gives an inner meaning to what is happening. Yet, this does not preclude the possibility of a practical use.

Figure 14.1 Engagement, power, meaning, pleasure

It should be noted that each of the resources if it is not optimally used, can become an anti-resource, a ‘black hole’, which is able to destroy life. We can say that each resource has a ‘shadow’ side, which is evident when resources become an independent value, when we lose touch with a larger context of human life. Then pleasure turns into the primitive pursuit of fun, with its simple dopamine spikes, its minimum investment and maximum side effects. Engagement becomes an addiction and power turns out to be a demand for hyper-control or adrenaline injection, while the super importance of meaning turns into fanaticism and an ‘idée fixe’. And conversely, ‘shadows’ can turn into potential resources.

It is important to remember that we should consider not only WHAT the resource is in the context of life, but also HOW and from what position (WHO) I deal with it. Within the resource position we answer the question: Exactly what condition and attitude helps me to move, grow, and cope with difficulties? As a result, we use three such positions in dance movement therapy:

And it is clear that there are practices and levels of skills in each of these positions, and there are other heroes (somewhere in other subjective worlds); but ask yourself, which position am I using when considering a situation in my life?

One of the ways of understanding the human psyche is that the subject evolves from the inter-subject or, in the words of Igor Kalinauskas: ‘People made of people’ (Kalinauskas, 2011, p. 19). In the integral approach we work with self-relationships, other people, the world, and eternity. Self-relationships mean healthy relationships with our own body and feelings, along with a balanced self-esteem and self-acceptance. When working with relationships with other people, we work with the ability to establish and maintain contact, express our own wishes and feelings, and define and protect our borders, etc. Relationships with the world can be seen as relationships with groups, communities, ‘socium’, or nature.

Relationships with other people can be a non-resource as well as a resource, sometimes they can be destructive and dysfunctional. In the context of psychotherapy and personal development, it is important for us to find re-source relationships and/or ways and strategies of behaving that can support the healthy aspects of relationships. We proceed from the fact that we already have the ‘therapist-client’ re-source relationships where the clients can learn ways to ask for support, demonstrate the right for their own space and time, and learn ways to really see The Other, without projections and expectations. In the realm of relationships, the dance gives plenty of opportunities to explore loneliness/contact balance, adequate and changing distance, the shift between leading and following, and other aspects of relationships.

Another interesting point – the same relationships can be a resource in one context, and a non-resource and a hindrance in another. Second person resources could be hypothetically divided into:

All these forms of resources can be found with the help of dance, real, or symbolic, and with the people in the room, or people from other aspects of our lives that are not present at this moment.

Material resources, such as money, property, and free time do not often feature as major aspects of dance movement therapy, but we can work with them to see how a person handles these resources in their daily life, and what scenarios and patterns are expressed during the dance with them.

Example 1: I (Alexander Girshon) really love my job, I like to hold classes, explore the world of movement, support people in their dance with life. Today I have a sufficient level of work all the time. Meanwhile, 5–6 years ago it became clear that I needed weekends and holidays, so as not to burn out at work. Besides, my full immersion in work could interfere with family relationships. So I started planning special vacations, where I could spend time with my family and children, without doing any great or important projects.

Example 2: Sometimes the topic of money is related to the ‘give/take’ balance, feelings of unworthiness, or a lack of the right to material reward. Acceptance is not only a psychological concept, it is always an internal action which has momentum. In dealing with this subject, we can study the ‘receive-accept-take’ spectrum of actions, which is associated with an increase in muscle tone and strengthening the aspect of Agency (author’s position). A good exercise for this topic: we share money with full awareness of the action, taking it on inhale and giving it on exhale.

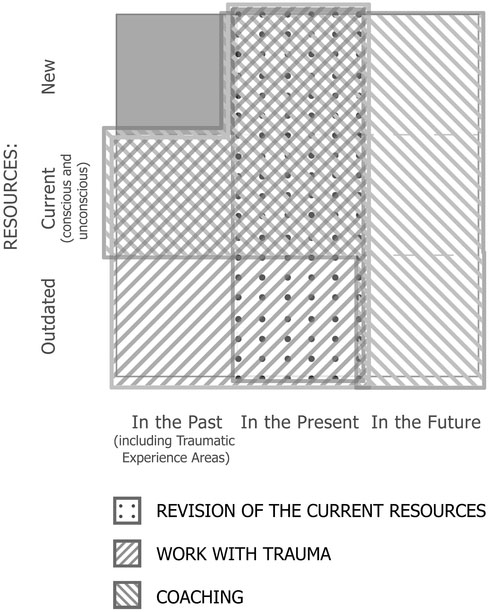

At the beginning of this chapter, referring to the etymology of the resource, we said that re-source can be seen as a ‘return to the source’. In addition, when working with psychological resources, it is also important to consider the ability to ‘let go’ and ‘provide’ yourself with new sources. In this approach, we can refer to resources from different time zones: the past (including fields of traumatic experiences), the present (resources revision often occurs here), and the future – in the form of appealing to resources as something to master within a given task (for example, to realise our own values).

Figure 14.2 Resources in a time continuum map

On the other hand, we can distinguish three groups of psychological resources:

Re-Sources, unknown before – they were unrealised and not ‘fitted’, or used; this is a new way of moving.

I try it, and it works out well; I like it and can benefit from it. Sometimes all you have to do is to notice them, sometimes you have to absorb them, or permit yourself to use them – then we will turn to ‘shadow’ re-sources.

As a result of reviewing these various psychological resource realms, we have created the ‘Resources in a Time Continuum Map’ (see Figure 14.2). We made this map when we were working simultaneously with different people in three different formats: developing, psychological, and coaching, as we had not had a clear understanding which resources to turn to within a particular format.

We have tried to list the psychological resources that we work with in dance movement therapy. This helps clients best handle their material resources, understand how they can build resourceful relationships, and how they can find their own internal resources. The main idea, which is the basis of this article is that you and your clients have access to many different resources, some that are available now and some that you need to work on. Or, slightly paraphrasing Erickson (1991), people always have enough resources for those changes that they need.

Cozolino, L. (2002). The Neuroscience of Psychotherapy: Building and Rebuilding the Human Brain. New York: W.W. Norton.

Erickson, M. (1991). My Voice Will Go with You: The Teaching Tales of Milton H. Erickson. New York: W.W. Norton.

Frege, G. (1979). Dialogue with Punjer on Existence. In H. Hermes, F. Kambartel, and F. Kaulbach (Eds.), Posthumous Writings (pp. 65–67). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Gendlin, E. T. (1996). Focusing-Oriented Psychotherapy: A Manual of the Experiential Method. New York: Guilford Press.

Kalinauskas, I. (2011). Alone with World. Moscow: Zikr Shop.

Kati, A., Stumpf, A., Heuft, G., Burgmer, M., and Schneider, G. (2015). Personal resources in inpatient psychotherapy – Relationships and development. Zeitschrift für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie/ Journal of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, 61(2), 139–155.

Lodrick, Z. (2007). Psychological trauma – What every trauma worker should know. The British Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 4(2), 18–28.

Porges, S. (1995). Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology, 32, 301–318.

Porges, S. (2001). The polyvagal theory: Phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 42, 123–146.

Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. New York: Free Press.

Wilber, K. (2000). Integral Psychology: Consciousness, Spirit, Psychology, Therapy. Boston: Shambhala Publications.

Wilber, K. (2003). Foreword in Frank Visser’s book. In Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (pp. xii–xiii). New York: State University of New York Press.

Wittgenstein, L. (2001). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. London and New York: Routledge Classics.