1 Warriors, War, and Resilience

The Warrior Class

Since the earliest recording of human warfare in 3,000 B.C.E., humankind has been at war with itself, punctuated by intermittent periods of relative peace. History textbooks of the United States and the world are often narratives of great human accomplishment and travesty, anchored to the chronology of war. On average, in any given year, there are 40 armed conflicts throughout the world. To survive in a realm where issues of human diversity, competition, and conflict are predominantly settled by violence, civilizations across time, national origin, and culture have always entrusted a special subgroup of its members, the warrior class, to protect and preserve that which is held most sacred and valued—even if it means forfeiting their health and life. In return, society forges a pact with its warrior class to honor its sacrifice and care for the visible and less visible wounds of the warrior and their family. To keep the hallowed promise requires a unique cadre of compassionate healers with specialized knowledge, skill, and the intrinsic desire to immerse themselves in the culture of the warrior. The inherent stress, danger, and sacrifice of the warrior life have required many societies to resort to conscription, compulsory service, or involuntary “drafts” in order to fill the rank and file. However, since 1973, the warrior class of the United States Armed Forces has been voluntary, along with most other countries in the modern world, though all have contingency plans for “selective service.”

MILITARY STRESS INJURY

The concept of stress injury is not unique to the military—or to war. However, an important paradigm shift is gaining increasing recognition, scientific credibility, and relevancy in the 21st century for institutions of military medicine, the warrior class, and their healers. Emerging is a contemporary understanding of the interdependent mind–brain–body connection and the neurodevel-opmental, accumulative effects of chronic, inescapable stress and potentially traumatic stress on physical and mental health (e.g., Bremner, 2005; Figley & Nash, 2007). Whereas ancient healers like Hippocrates relied upon observations of how life experiences impact human physiology and health, today’s healers have the cumulative weight of decades-long investigations from the diverse fields of biology, immunology, lifespan development, neuroscience, epidemiology, medicine, mental health, military, history, comparative experimentation, and cultural anthropology.

PURPOSE OF THE BOOK

The aim of this book is to cover the full range of possible military stress injuries, including stress injuries from trauma other than combat or war. Occupational hazards of military service regularly involve exposure to a plethora of chronic, inescapable, and uncontrollable stressors (e.g., deployments and frequent geographical relocations), as well as a host of potential traumatic events, such as combat, sexual violence, disaster relief, training accidents, and peacekeeping missions, that can have profound short- and long-term effects on military members’ health and their families. Historically, research and treatment for the military population have narrowly focused on a select number of traumatic stress injuries such as combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression, overlooking the full spectrum of other predictable stress injuries that men and women in uniform may experience, especially medically unexplained symptoms (e.g., Russell, 2008c). Despite stringent efforts to prevent and treat conditions like PTSD, the graded dose of length, intensity, and frequency of exposure to chronic, inescapable, and/or traumatic stressors has progressively led to escalations of behavioral health challenges. Research has succeeded in identifying a host of markers—biological, psychological, interpersonal, and environmental—that predict when combatants are likely to develop war stress injuries that, like any progressive disease, when left unattended, can metastasize into severe, debilitating, and sometimes fatal health problems for veterans and their families.

THE SPECTRUM OF WAR/TRAUMATIC STRESS INJURIES

Nearly all written accounts of war or combat stress, regardless of place in time, culture, or national origin, describe a wide range of stress-related injuries that can best be divided (albeit artificially) into two major classifications: neuropsychiatric and medically unexplained symptoms (MUS), often called “war syndromes,” “psychosomatic illness,” or “hysteria” and currently lumped into the Veterans’ Health Administration (VHA) category of Symptoms, Signs, and Ill-Defined Conditions (SSID). Historically, military, medical, and psychiatric professionals have classified war stress injuries based upon a particular constellation or pattern of physical and psychological symptoms that comprise the ubiquitous human reaction to unrelenting and/or traumatic stress emphasized at a given time and cultural understanding (e.g., Russell, 2008c). Consequently, a plethora of labels, diagnostic (e.g., nostalgia, war hysteria, shellshock, PTSD) and socio-political (e.g., lacking moral fiber, battle fatigue, pension-neurosis), have emerged during each war generation, each describing ways in which human beings adapt to the inherently toxic stress of war.

Neuropsychiatric Conditions

Neuropsychiatric terms used during the world wars and Vietnam included traditional psychiatric diagnoses of the times, such as “traumatic neurosis,” “shellshock,” “nervous shock,” “neurasthenia,” “melancholia,” “combat neurosis,” “alcoholism,” “transient situational disturbance,” “psychopathic personality,” or “insanity” (Jones & Wessely, 2005). In the 21st century, neuropsychiatric diagnoses include major depression disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, substance-use disorders, traumatic brain injury, acute stress disorder, personality disorder, and PTSD, and these are the psychiatric conditions that receive the predominant focus by the military and public sector in terms of assessing the psychological toll of war (e.g., Russell, 2008c). However, what actually is identified, diagnosed, and counted as a neuropsychiatric casualty has never been consistent within or across military institutions from one war to the next, especially before the First World War (1914–1918). This has led to the false perception that dramatic escalations in war stress-injuries like PTSD are unique to the modern warrior class due to the weakening influence of 20th-century psychiatry and a “culture of trauma” (Shepard, 2001), as opposed to efficiencies of modern industrialized warfare.

Medically Unexplained Symptoms/Conditions

Modern estimates of the prevalence of war stress injury are generally limited to a handful of neuropsychiatric diagnoses (e.g., PTSD, TBI, depression, etc.) and completely exclude the other half of the equation—medically unexplained symptoms (MUS). As a consequence, all or nearly all of institutional military medicine’s research, training, and treatment resources, as well as clinical books and manuals written on war trauma, ignore MUS. To our knowledge, this is the first treatment-oriented book to address the full spectrum of war stress injury. It is critical for mental health practitioners to understand, identify, and treat the whole person, which includes MUS. Therefore in order to make up ground in the knowledge deficit of MUS, we offer an overview.

War Stress and Medically Unexplained Symptoms

A progressively strong association between the prevalence rates of medically unexplained symptoms with technological advances in killing, stress, and terror is well chronicled by military medical historians since the Napoleonic era (e.g., Jones & Wessely, 2005). Similarly, changes in tactics have evolved to inflict psychological and social wounds as much as physical casualties in order to demoralize and defeat one’s enemy (e.g., chemical-biological-nuclear weaponry, mass bombing of civilian populations, guerilla tactics, terrorism). The accumulative toxic psychosomatic effects of modern industrialized warfare gradually emerged as various war syndromes were identified during 1854–1895 Victorian-era campaigns (e.g., “wind contusion,” “palpitation”); 1860–1865 American Civil War (e.g., “irritable heart,” “mental aches”); and 1899–1902 Boer War (e.g., “disordered actions of the heart”; Jones & Wessely, 2005). However, the full psychophysical assault from modern war was not fully realized until the First World War (1914–1918), resulting in unprecedented, epidemic numbers of medically unexplained casualties—spurring cyclical, impassioned, and unresolved debates regarding etiology, treatment, and compensation of war stress injuries that continue today (e.g., Russell, 2008c).

Historically, military medical institutions have not clearly differentiated between neuropsychiatric and medically unexplained symptoms, and they avoid using terms like “war syndromes” that insinuate causal effects of war. Common inexplicable psychophysical symptoms include chronic fatigue, muscle weakness, sleep disturbance, headache, back pain, pseudo-seizures, diarrhea, muscle aches, joint pain, memory problems, concentration difficulties, gait disturbance, pseudo-paralyses, constipation, erectile dysfunction, nausea, gastrointestinal distress, lump in the throat, shortness of breath, pelvic pain, abdominal pain, dysmenorrheal, paraesthesias, fainting, sensory loss, dizziness, irritability, rapid or irregular heartbeat, skin rashes, persistent cough and tremors, and shaking or trembling (e.g., Jones & Wessely, 2005).

The understanding, diagnosis, treatment, and reporting of MUS in civilian, veteran, and military populations are greatly complicated by the inherently diverse and vague diagnostic labels that suggest a known pathological cause where none may exist. Examples of contemporary diagnoses of medically unexplained conditions include: chronic fatigue syndrome; fibromyalgia; irritable bowel syndrome; chronic pelvic pain; idiopathic epilepsy; multiple chemical sensitivity; myofacial pain syndromes; functional dyspepsia; somatoform disorders; hyperventilation syndrome; globus syndrome; and non-cardiac chest pain (NCCP; e.g., Russell, 2008c). However, all such labels describe a portion or subset of the human stress response spectrum and do not preclude actual physical etiology. How prevalent are MUS in military clientele?

War Psychiatric Lessons Unlearned: Prevalence of MUS During World War II

War and traumatic stress injuries may manifest and/or be diagnosed as only a neuropsychiatric syndrome(s) such as PTSD, major depression, and so on; as medically unexplained symptom(s) such as chronic fatigue, non-ulcer dyspepsia, and so on; or as a combination of both (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder and pseudo-[atypical] seizure disorder). The latter represents the norm; however, it is exceedingly common for military personnel to seek out and receive medical treatment for multiple unexplained somatic complaints for years, without any consideration of connecting the mind and body.

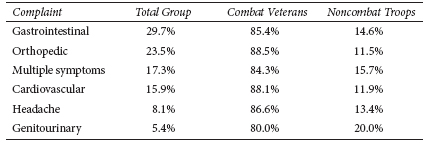

Table 1.1 Incidence of Psychosomatic Complaints (Menninger, 1948, p. 156)

As observed by WWII Chief Consultant in Neuropsychiatry to the Surgeon General of the U.S. Army, Brigadier General William C. Menninger (1948), and his distant predecessor Union Army Surgeon General William A. Hammond (1883), “psychosomatic” or MUS are by far the most predictably prevalent, least understood, and most under-treated manifestation of stress injury during war. In his post-war memoir, General Menninger (1948) writes: “By some people ‘psychosomatic medicine’ is used to refer to a limited number of diseases. By others, including the author, it is regarded as a guiding principle of medical practice which applies to all illness” (p. 153). The Army General based his conclusions on sobering War Department statistics revealing the toxicity of war stress on health, such as those listed in Table 1.1.

Institutional Military Medicine and MUS

Menninger’s (1948) observations were shared by previous enlightened military medical leaders, Army Surgeon General William A. Hammond and Army Surgeon S. Weir Mitchell, who were convinced that “nerve injuries” and nervous disorders, as they were broadly categorized, were both real and treatable (Lande, 2003). Hammond and Mitchell rejected not only the prevailing explanation that afflicted soldiers were all either cowards, deserters, or malingerers, but they also abandoned dualism itself and proposed instead a “mind–body unitary theory” by describing emotional and physical symptoms as inseparably intertwined, thereby removing critical barriers to understand, study, and treat war stress injuries (Hammond, 1883). More recently, the short-lived Gulf War (1990–1991) resulted in over 100,000 of 700,000 U.S. personnel deployed to the Persian Gulf theater reporting medically unexplained symptoms (e.g., chronic fatigue, pain, insomnia, etc.), leading to another controversial syndrome “Gulf War Illness” (Ozakinci, Hallman, & Kipen, 2006). To be clear, we are not suggesting that all or most cases of Gulf War Illness were not caused or exacerbated by medical or environmental pathogens. Stability of Gulf War Syndrome in 390 Gulf War veterans revealed no significant alteration in symptom number or severity over a 5-year period (Ozakinci et al., 2006)—requiring better understanding, early identification, and treatment of war syndromes while on Active duty to prevent long-term disability (e.g., Russell, 2008c).

MILITARY DEFINITIONS OF STRESS-RELATED DISORDERS AND SYNDROMES

To enhance accurate communication between mental health providers, military clientele, and military organizations, the following definitions are adapted from the Department of Veteran’s Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DoD) October, 2010 VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Post-Traumatic Stress. Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs and Health Affairs, Department of Defense. Office of Quality and Performance publication 10Q-CPG/PTSD-10: Washington, DC:

Acute Stress Reaction (ASR)

Acute stress reaction is a transient condition that develops in response to a traumatic event. Onset of at least some signs and symptoms may be simultaneous with the trauma itself or within minutes of the traumatic event and may follow the trauma after an interval of hours or days. In most cases, symptoms will disappear within days (even hours). Symptoms include a varying mixture of the following.

Combat and Operational Stress Reaction (COSR)

Technically, the DoD-approved term for official medical reports is “Combat Operational Stress Reaction” and it is applied to any stress reaction in the military environment. COSR refers to the adverse reactions military personnel may experience when exposed to combat, deployment-related stress, or other operational stressors. COSR replaces earlier terminology like “battle fatigue” or “combat exhaustion” used to normalize “acute stress responses” (ASR) related to deployment and war-zone stressors and acute “combat stress reactions” (CSR) associated with exposure to combat.

“Post-Traumatic Stress.” Recently, military leaders have increasingly embraced the term “Post-Traumatic Stress” or “PTS,” which mainly refers to what is sometimes called “sub-clinical PTSD” in medical settings. The preference within the military is to omit reference to “disorder” by dropping the “D” in PTSD; however, most military personnel do not make the distinction between ASR, CSR, COSR, or PTS. Military members may disclose, “I’ve been diagnosed with PTS,” which may mean a clinical condition (PTSD) or a sub-clinical, transient reaction.

Table 1.2

Common COSR Symptoms

The onset of at least some signs and symptoms may be simultaneous with the acute stressor or trauma itself or may follow the event after an interval of hours or days. Symptoms of COSR may include depression, fatigue, anxiety, decreased concentration/memory, irritability, agitation, and exaggerated startle response. See Table 1.2 for a partial list of signs and symptoms following exposure to COSR including potentially traumatic events (VA/DoD, 2010).

Spiritual or Moral Symptoms

Service members may also experience acute or chronic spiritual symptoms such as:

• Feelings of despair

• Questioning of old religious or spiritual beliefs

• Withdrawal from spiritual practice and spiritual community

• Sense of the doom about the world and the future

Resilience, Adaptive Stress Reactions, and Post-Traumatic Growth

Discussions on military- and war-related stressors are often unfairly slanted toward the negative, aversive, and horrific aspects of going to war or a disaster zone and hopelessly fail to recognize many positive or adaptive outcomes. The term “adaptive stress reactions” refers to positive responses to COSRs that enhance individual and unit performance. Post-traumatic growth refers to positive changes that occur as a result of exposure to stressful and traumatic experiences. Many service personnel, especially combat veterans, often regard their war-time experiences with mixed appreciation as being one of their “best,” “hardest,” and “worst” life events. The following is a sample of potential adaptive outcomes from combat and operational stressors:

• Forming of close, loyal social ties or camaraderie never likely repeated in life (e.g., band of brothers and band of sisters);

• Improved appreciation of life;

• Deep sense of pride (e.g., taking part of history making);

• Enhanced sense of unit cohesion, morale, and esprit de corps; and

• Sense of eliteness.

Misconduct Stress Behaviors

Misconduct stress behaviors describe a range of maladaptive stress reactions from minor to serious violations of military or civilian law and the Law of Land Warfare, most often occurring in poorly trained personnel, but “good and heroic [Soldiers], under extreme stress may also engage in misconduct” (Department of the Army, 2006, pp. 1–6). Examples include mutilating enemy dead, not taking prisoners, looting, rape, brutality, killing animals, self-inflicted wounds, “fragging,” desertion, torture, and intentionally killing non-combatants.