6 Phase Two:

Client Preparation and

Informed Consent

After completing Phase One, the therapist readies the client for EMDR therapy by strengthening the collaborative, therapeutic alliance through discussing the assessment results, treatment options, and the initial treatment plan. If the client opts for a trial of EMDR, practitioners provide the client an explanation of traumatic stress injuries, and a working hypothesis of EMDR treatment. The procedural method of EMDR is then reviewed and demonstrated, along with client and therapist expectations. The second phase may conclude with an in-session stress management practice session that typically involves introducing dual-focused attention and bilateral stimulation. Clients deemed too unstable or unsuitable for EMDR reprocessing will continue with preparatory sessions utilizing variant EMDR procedures like Resource Development and Installation (RDI).

ENHANCING THE THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIP

Earlier we mentioned that there are times and settings within the military (e.g., forward-deployed, operational environment), whereby the EMDR intervention maybe limited to a 1–2 sessions. Therefore a workable alliance needs to be established very quickly. The history taking and target selection will be significantly abbreviated and narrowly focused on the precipitant event. In these scenarios, client preparation moves extremely quickly. This is obviously quite different for therapists implementing the standard EMDR protocol. We will cover both scenarios in this section.

ACUTE STRESS REACTIONS/COSR IN THE MILITARY AND EMDR EARLY INTERVENTION

Acute interventions can be envisioned as the mental health correlate of physical first aid, with the goal being to “stop the psychological bleeding.” The first, most important measure should be to eliminate (if possible) the source of the trauma or to remove the victim from the traumatic, stressful environment. Once the patient is in a safe situation, the provider should attempt to reassure the patient, encourage a professional healing relationship, encourage a feeling of safety, and identify existing social supports. Establishing safety and assurance may enable people to get back on track, and maintain their pretrauma stable condition. Some want and feel a need to discuss the event, and some have no such need. Respect individual and cultural preferences in the attempt to meet their needs as much as possible. Allow for normal recovery and monitor.

Recommended Interventions for COSR

According to the DVA/DoD (2010) Clinical Practice Guideline, Combat Operation Stress Control (COSC) utilizes the management principles of brevity, immediacy, contact, expectancy, proximity, and simplicity (BICEPS). These principles apply to all COSC interventions or activities throughout the theater, and are followed by COSC personnel in all mental health and COSC elements. These principles may be applied differently based on a particular level of care and other factors pertaining to mission, enemy, terrain and weather, troops and support available, time available, and civil considerations. The actions used for COSC (commonly referred to as the 6 Rs) involve the following actions:

• Reassure of normality (normalize the reaction)

• Rest (respite from combat or break from work)

• Replenish bodily needs (such as thermal comfort, water, food, hygiene, and sleep)

• Restore confidence with purposeful activities and talk

• Retain contact with fellow Soldiers and unit

• Remind/Recognize emotion of reaction (specifically potentially life-threatening thoughts and behaviors)

Early Treatment of Severe ASR/COSR and ASD

In regards to intervening with severe ASR/COSR and ASD, the DVA and DoD (2010) recommend the following:

• Acutely traumatized people who meet the criteria for diagnosis of ASD and those with significant levels of post-trauma symptoms after at least two weeks post-trauma, as well as those who are incapacitated by acute psychological or physical symptoms, should receive further assessment and early intervention to prevent PTSD. Trauma survivors, who present with symptoms that do not meet the diagnostic threshold for ASD, or those who have recovered from the trauma and currently show no symptoms, should be monitored and may benefit from follow-up and provision of ongoing counseling or symptomatic treatment.

• Service members with COSR who do not respond to initial supportive interventions may warrant referral or evacuation.

Prepping for EMDR

After addressing the acute needs of military members, including possible implementation of BICEPS and the COSR “6 Rs,” some or many personnel may continue to be negatively impacted, and develop severe debilitating ASR/COSR or even Acute Stress Disorder (ASD). According to the DVA/DoD (2010), individuals developing ASD are at greater risk of developing PTSD and should be identified and offered treatment as soon as possible. In order to stabilize, reduce, or heal the worsening stress injury, early interventions such as EMDR or a variant may be helpful. Unfortunately, due to institutional military medicine’s ban on EMDR research (see Chapter 3, this volume), only case studies and anecdotal clinical reports have been published on EMDR treatment for acute war stress injury, but controlled and uncontrolled reports on EMDR and ASR in the civilian sector have been reviewed (e.g., Shapiro, 2009). Nevertheless, the Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Post-Traumatic Stress (DVA/DoD 2010) have concluded that cognitive-behavioral techniques are the current early intervention of choice. Although the military’s practice guidelines do not single out EMDR as an early intervention per se, EMDR is explicitly listed by the guidelines as a trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral treatment that is evidence-based for the treatment of traumatic stress injuries. Therefore EMDR can and should be reasonably considered a viable frontline option. A variety of situations in the military may arise, whereby there is a very tight window for intervening with EMDR and the extent of client history taking and rapport building is extremely compressed.

EMDR STABILIZATION INTERVENTIONS

In Chapter 5 we provided an outline of treatment options including specific EMDR-related protocols for addressing the treatment goal. The first treatment goal is client “stabilization.” Below is a description and example of the protocol for each of the EMDR-related interventions that might be used explicitly to enhance client stability either to refer to a higher echelon of care, or to prepare for EMDR reprocessing. The three stabilizations procedures were Emergency Response Procedure (ERP), Eye Movement Desensitization (EMD), and Resource Development and Installation (RDI).

Emergency Response Procedure (ERP)

Purpose: Stabilization of client by increasing orientation to present focus. Gary Quinn, an Israeli psychologist, reported utilizing a modified EMDR protocol he called Emergency Reprocessing Procedure (ERP; Quinn, 2009). Following a terrorist bombing incident in Israel, traumatized patients were brought to emergency rooms, and Dr. Quinn was on call. Clients suffering from acute stress reaction sat in “shock” and were unresponsive to verbal questions or commands by medical personnel needed to perform triage. After routine attempts to engage the blankly starring client, Dr. Quinn contemplated whether an EMDR-variant might reach the client. Speaking calmly in the client’s ear, Dr. Quinn identified himself and his role in the hospital, and he reassured the client of their safety in the hospital. Afterwards, he informed clients that he was going to tap them gently on the shoulder and remind them where they are, that they had survived the bombing, and they were now at a safe place. After brief periods of the bilateral taps and therapist-directed attention to safety, clients became responsive to outside stimuli and could then be engaged verbally about their medical status and so on. To our knowledge this has not been tested or replicated in military settings. In regards to the therapeutic alliance and client preparation, even in emergency scenarios like this, the therapist conveyed a caring, respectful, and empathic approach toward acutely distressed clients, and provided a measure of control by informing the client of each step to be taken. The total intervention time would be measured in minutes (see Quinn, 2009).

Eye Movement Desensitization (EMD)

Purpose: Reducing primary symptoms associated to the precipitating event only. In the immediate or near-immediate aftermath of exposure to severe or potentially traumatic event, personnel may present with severe, debilitating ASR/COSR. If the client is conscious and medically cleared but presents as acutely dissociated and verbally unresponsive (AKA psychic shock), then the therapist should consider ERP or another grounding technique instead. If forward-deployed, the client has either refused or not responded to standard medical/Combat (Operational) Stress Control or other supportive interventions. Or medical/clinical/unit personnel—or the client his/herself—have requested intervention to stabilize neuropsychiatric symptoms in order to further assess, return to duty, or move to higher echelon of care. For instance, the client is too unstable for aeromedical or other transportation. If symptoms are severe and include dissociative and traumatic stress symptoms, the client may meet diagnostic criteria for Acute Stress Disorder (1–30 days). All basic safety needs and medical triage, if indicated, have been completed. A referral question from medical/nursing, unit medical or command, or other emergency personnel is for the therapist to assist with reducing primary symptoms sufficient for psychological stabilization and movement to next higher echelon of care. Treatment focus is crisis intervention limited to the precipitating event.

EMD Description

EMD is essentially a behavioral exposure therapy that incorporates bilateral stimulation (BLS) in a desensitization paradigm, with BLS serving as the reciprocal inhibitory response to the client’s stress-response. In EMD, the therapist does not reinforce or pursue free associations outside of the singleincident precipitating event.

EMD Stabilization Protocol

Client history, preparation, and informed consent. When possible, obtain information about the precipitating event, and the client’s involvement should be obtained from the referral source (e.g., medical, nursing, or unit personnel). The therapist introduces himself, his role, and the reason for referral. The therapist should ask, “Is it okay if I talk to you?” If the client consents, ask him or her to share the narrative of the event and his or her involvement. See the case study for Acute Stress Injury below for further information related to history, preparation, consent, etc.

Selecting Target Memory: Ask the client, “What is the most disturbing part to you about what just happened?” or words to that effect. Remember to keep the focus on the precipitating event. Only one past memory is selected. Current trigger and future desired behavior are not targeted.

Image or sensory memory: “Is there one image or picture in particular, that represents the worst part of that gravesite (name the incident) scene?”

Negative Cognition: “All right, so as you keep thinking about the gravesite (name the incident) memory, and the picture of the __________ (name the image),

what words go best with that picture that expresses your negative belief about yourself now?

Note: The Positive Cognition and VOC are not usually assessed in EMD for stabilization purposes, as the intention is symptom reduction and stabilization. Installation and Body Scan Phases are not included.

Emotion: “When you think of this dog incident and the words ‘I can’t stand it anymore,’ what feelings or emotion come up?”

SUDS Rating: Ex. “I can see you’re in a lot of pain Staff Sergeant, on a 0 to 10 scale, 0 you feel no distress or other disturbance and 10 the worst disturbance you can think of, how disturbing does it feel now?”

Physical Sensations and Location: “And where do you feel it in your body?”

Reprocessing: After the therapist writes down the location of the physical sensations say, “Ok, pay attention to those (name physical sensations) in your (state body location) and that picture (name the picture) and follow my hand with your eyes” and slowly start the eye movement (EM) and make sure they are tracking, then speed up as fast as they track. Be aware that dissociative symptoms like derealization and depersonalizing make it more difficult to concentrate on external stimuli, so the EM speed can be slower than nonacute, dissociative states. Changing direction, flickering of the fingers, and verbal prompts by the therapist may prevent the client from habituating to the stimulus.

Dual-Focused Attention: It is vitally important to maintain the client’s dual-focused attention during the reprocessing by talking to the client, “That’s it … good … just keep tracking … you’re safe now … that’s it … just notice it … you’re safe now … good … it’s in the past …” etc. In Chapter 9, a treatment case study is provided with a solider presenting with a high level of dissociation, and it is apparent how verbally engaged the therapist needs to be at times to prevent self-absorption and maintain the dual-focus.

Reprocessing to Completion: If during BLS, the client reports a free association that appears unrelated to the precipitating event, gently say “Ok, now I would like you to go back to the bombing incident (name the event), what do you notice now?” Obtain a SUDS rating each time the client returns to the target memory. After obtaining the SUDS instruct, “Just think of that….” Repeat this sequence each time the client self-reports an association outside of the treatment parameter. The client may be returned to the target memory and asked for a SUDS rating any time the therapist wants to check the progress of the desensitization effect. Repeat the process until target memory has a SUDS of “0” or “1” if ecologically valid. Installation, body scan, current triggers, and future template are not included.

Reevaluation: Generally, it is a good idea to contact the client, their medical attendant, or command within a day to check on the client’s condition. If appropriate, additional reprocessing (e.g., EMD, EMDR) or strengthening resilience (e.g., RDI) may be recommended.

Resource Development and Installation (RDI)

Client history taking may reveal that certain clients are too unstable or not appropriate for reprocessing due to temporary time constraints, emotional or behavioral instability, or poor self-regulation skills. Resource Development and Installation (RDI) was developed by Drs. Andrew Leeds and Debra Korn as a means to enhance or strengthen the client’s access to internal “resources” associated with their adaptive neural networks (Leeds, 2009). During EMDR client history taking or preparation, the client was determined to be unsuitable for EMDR reprocessing due to emotional or behavioral instability, safety, or other clinical indicators including time or environmental constraints (see Chapter 5, this volume). The referral source may be medical/clinical/unit or other involved personnel, including client self-referral requesting treatment, possibly specifically EMDR. The potential need and use of RDI are evident by the high prevalence of pre-military history of trauma and other adverse childhood experiences in newly accessioned military personnel. Moreover, according to the DVA/DoD (2010) post-traumatic stress guidelines, individuals with severe childhood trauma (e.g., sexual abuse) may present with complex PTSD symptoms and parasuicidal behaviors (e.g., self-mutilation, medication overdoses) (Roth et al., 1997, cited in DVA/DoD, 2010). Further, limited cognitive coping styles in PTSD have been linked to a heightened suicide risk (Amir et al., 1999, cited in DVA/DoD, 2010). Fostering competence and social support may reduce this risk (Kotler et al., 2001, cited in DVA/DoD, 2010). Co-morbid substance use disorders may increase the risk of suicidality. Additionally, persons with PTSD may also be at personal risk of danger through ongoing or future victimization in relationships (e.g., domestic violence/battering, or rape).

Clinical findings revealed the client requires additional adaptive resources in order to be adequately stable and appropriate for future EMDR reprocessing. If forward-deployed or in an operational environment, the principle aim is to stabilize the client’s emotional or behavior state by increasing their access to adaptive, coping resources. This is appropriate for any acute or chronic neuropsychiatric and/or medically unexplained condition consistent with a war stress or other traumatic stress injury. Possible indications that the client may not be adequately stable or suitable for EMDR reprocessing are reviewed on pages 79–82. The following are potential resources targets (from F. Shapiro, 2005; used with permission):

Types of Possible Resources

Mastery: Experience of past coping, self-care, or self-soothing stance or movement that evokes needed state.

Relationship: (a) Positive role models, (b) Memories of supportive others.

Symbolic: (a) Natural objects that represent the needed attribute, (b) Symbols from dreams, daydreams, or guided imagery, (c) Cultural, religious or spiritual symbols, (d) Metaphors, (e) Music, (f) Image of positive goal state or future self.

RDI Protocol

1 Identifying the Resource: “When you think about that memory (or incident) what positive resource, skill, or strength would help you to deal better with the situation?”

2 Explore the Most Helpful Resource: (mastery experience, relational resource, or symbol/metaphor): “Has there been a time or a situation in your life when you have successfully used that __________________ (resource, skill, or strength)?” If the client answer is no, then: “Do you know anyone who has this quality? Or can you think about someone who has this quality? Or a character from a book, movie, or TV?” If the answer is still no, then: “What image or symbol or metaphor might represent this resource?”

3 Add Emotions and Sensations: “When you think about this resource, is there an image that comes to mind?” “And when you think about the resource and that image, what emotions do you notice?” “And what physical sensations do you notice?”

4 Checking the Resource: “When you think about that challenging memory (or situation) would being able to use this resource be helpful?” “Can you rate how helpful it would be on a scale of 1 to 7 where 1 is not helpful at all and 7 is very helpful?” “And can you think about that resource and the related image, emotions, and feelings without any negative associations or feelings?” If not helpful at all, or if the client can’t connect without negative associations, then return to Step 2 and identify a different resource.

5 Resource Installation: “Now bring up that resource, and the image, the emotions, and notice where you feel it in your body … than follow my fingers.” Add short sets (6–12) of bilateral stimulations (BLS). Then, “What are you noticing now?” If positive, add another few short sets of BLS. After each set, ask what the client is noticing.

6 Cue Word-Par With a Word or Symbol: “Is there a word or a symbol that could represent this resource?” Pair word or symbol with resource and add short-sets of BLS. After BLS, always ask clients what they are noticing now.

7 Future Desired Outcome: “Now hold that resource together with the thought of that challenging memory (or situation) … and follow my fingers.” Add short sets of BLS: “You can feel that resource exactly as you need to feel it.” “You can experience that resource exactly as you need to experience it.”

8 Verify the usefulness of the Resource: “Now when you think about that challenging memory (or situation) how useful would this resource be on a scale of 1 to 7, where 1 is not helpful at all and 7 is very helpful?”

9 Practice and Reevaluation: Ask the client to practice bringing up the resource between sessions. The therapist can access and strengthen the resource prior to trauma work. Reevaluate the strength and usefulness in future sessions.

CASE STUDY: CLIENT PREPARATION FOR ACUTE WAR STRESS INJURY

Another example of a time compressed military environment is one that the author (Mark Russell) is immanently familiar with. A 250-bed Navy field hospital served as one of two aeromedical evacuation points for Iraqi battlefield casualties at the outset of the invasion. A high OTEMPO environment, aircraft would land daily, unload medical casualties, and load and transport those stable enough to Walter Reed. We ran a neuropsychiatric service that included a reconditioning ward, and screened over 1,300 evacuees for war stress injury (Russell et al., 2005). The average length of patient stay was 2–3 days, so there was very high OPTEMPO. Four wounded military personnel were referred to the author (Mark Russell) because they were too severely debilitated by their combat stress injury, and were not stable enough for medical transport within the next few days (the following was adapted from Russell, 2006). To make a long story short, the author met with each client on the ward and utilized the following EMD protocol:

Client History (15 minutes):

Referral question. As we discussed earlier, the referral question is pivotal for treatment planning. In this case, we knew the clients would be leaving within the next 1–3 days, but possibly as early as the next day if their war stress injury stabilized. Therefore it was evident that the standard EMDR protocol was impractical, as were possibly other procedural steps that we will discuss in order. With the AIP model as a guide, previous clinical experience with EMDR dictated that by focusing on the most emotionally charged memory related to the client’s presenting complaint, we should be able to see a reduction in symptom intensity, hopefully, to the point of stabilizing the client’s condition so they can be transported to the next echelon of care. Neither the referral source nor the client, were requesting a “cure” of the war stress injury, and if they had, it would be prudent to indicate that the current time and environmental constraints would make that hard at best. No, the referral question was clear, and the treatment plan was designed accordingly.

Establishing a therapeutic alliance. Introduction, reviewed reason for referral, and informed consent was obtained to speak with a mental health staff. The therapist attempted to establish rapport and trust by communicating genuine care, concern for the client’s well-being, empathy, and a desire to help, as well as respectfully informing clients of the reason and purpose of the visit, and asking permission to speak to the clients about their current difficulties.

Selecting past target memory—worst memory from deployment. In the operational setting, client history was limited to inquiring about the client’s presenting complaint, and more specifically, to the most disturbing event that was causing the debilitating acute stress reaction. This was solicited by asking clients something like: “If you had to pick one thing that stands out, what is the most disturbing event that’s bothering you the most right now?” As the clients shared their combat narrative, the author (Mark Russell) jotted down details of the incidents given along with their descriptive phrases which would be used to convey empathic understanding.

Selecting current and future target memories. The therapist did not solicit current trigger and future template. The best explanation as to why is that it has been the author’s (Mark Russell) experience with EMDR that the generalization effect from reprocessing the most highly emotionally charged past memory, tends to greatly diminish and sometimes ameliorate the current trigger and future anticipatory anxiety, etc. The other reason for by-passing the three-pronged protocol was time, the referral question, and the client’s goals.

Client stability. Clients were asked if they have any active suicidal or homicidal thoughts. Afterwards, clients were asked if they were up to continuing, as many became quite visibly distressed in relaying the “worst” part of their deployment experience.

Baseline symptom measures. All clients were asked to complete the Impact of Events Scale. All clients meet criteria for either acute combat-stress disorder or acute-combat PTSD.

Client Preparation (10 minutes):

Enhancing therapeutic trust and rapport. The therapist continued to build rapport by communicating in a caring, respectful, empathic manner. Emphasis was on clients having control over the consent process as well as EMDR session itself.

Informed consent about treatments. “There might be something we could do to help with some of the worst parts of your memories so that you might be able to sleep and go home without the memories bothering you as much as they are right now. However, I cannot guarantee that the treatment will work for you. I can also recommend to the psychiatrist to prescribe something to help you sleep and reduce some of your symptoms, either instead of EMDR, or after treatment if you need it. If you do choose a trial of EMDR, you will still need to follow up at your CONUS MTF (stateside hospital) to make sure that things haven’t changed for the worse. EMDR stands for eye movement desensitization and reprocessing; a mouthful, I know, which is why we just say EMDR. In a nutshell this is what we will do: I’m going to ask you some questions just to get an enough of an idea of what’s giving you these nightmares. If you don’t want to answer a particular question, or any questions, that’s entirely up to you. In normal EMDR we would let your memories shift anywhere they need to go including before you joined the military. What we’re going to do in this case is keep the focus just on the immediate issue that’s giving you the hardest time. Almost all of the time, you’re going to know before I do if things are changing for you or not, and whether it is helping. Doing the eye movements will require you to revisit some bad experiences, but it sounds like that’s already happening anyways. From time to time, I’ll ask you to give me a 0–10 rating, so we both know where things are going. Any questions? Is this still something that you want to try or do you want to look at other options?”

Stop signal was established. “During EMDR you are the one in control, so anytime you want to stop, we stop, no questions asked … however just so that I am clear, if you want me to stop, in addition to saying “stop,” is there a hand signal or something you can also give me … so that I know you mean for ME to stop, and not something that you are remembering?” Client chose to raise his hand and say “stop.”

Brief EMDR procedural overview. “I am going to ask you to bring up the memory of X, and, at the same time, while you are wide awake I am going to ask you to follow my fingers with your eye, like this … (demonstrated diagonal eye movements that client’s tracked with their eyes) … that’s it, just track my hand with your eyes only.”

Clarifying therapist and client role expectations. “I’ve been using EMDR for many years now, and each person has a slightly different experience … sometimes they report the memory changes to another memory, or the image might change, the feeling, people’s thoughts, or physical sensations might change … sometimes people report nothing changes … when we start EMDR, I just need you to tell me honestly what you are noticing, you don’t have to tell me all the details, and you can tell me as much as you like, the main thing that I need to know, is if something is changing or not, does that make sense?”

Informed consent regarding potential pros and cons of using EMDR. “I need to also tell you that it is common when we use EMDR that people may remember things very clearly, just like it was when it happened the first time; the thing to remember is that it has already happened and is just a memory, so you are safe here. But that can happen…. The other thing is that people report that, when they start EMDR with one memory, it might shift to other memories, including things that happened long ago, like in childhood, but are somehow maybe related to the current event … so I want you to know that those are some of the things that ‘might’ happen…. Again, for some people nothing might happen … does that seem clear to you? Do you still want to go forward with EMDR, or maybe try something else?” All clients selected to stay with EMDR.

Review of theoretical models. There was no explanation of the theoretical model of acute stress disorder or PTSD, nor was there an explanation of EMDR theory. Time was one consideration, but mainly it seemed inappropriate because of the acute nature of their distress to lecture, however briefly, about what we think is going on in the brain, or why EMDR works; it seemed to be information overload. However, as it would turn out, clients did ask about EMDR theory after the session as they grappled with understanding what just happened.

Stress reduction methods. No instruction on calm/safe place or any other coping skill was given. The reason was because of time consideration, and teaching calm or safe place immediately after being medically evacuated from war, struck me as problematic. Many patients I spoke to were infinitely more upset about having to be evacuated away from their unit members, than the wounds or injuries they sustained. At any rate, I chose to forgo the practice session, and move onto Phase Three.

Clinical Note. All four interventions went according to the script described above. The actual time spent on the first two phases maybe shorter for some, or slightly longer for others, but generally speaking, things moved quick and for a purpose. The author (Mark Russell) had confidence in the AIP model and the potential generalization effects of EMDR, even when there was deviation to the standard protocol. Those modifications, however, were in concert with the exigencies at the time. There was no pretense that a single session of a modified EMDR, what some have referred to as “EMD,” was going to permanently resolve the client’s acute war stress injury, and this was appropriately communicated to every client. Emphasis on honest, respectful, and empathic communication, along with seizing opportunities to instill a sense of client agency or control, was intentional, and served to create the therapeutic conditions for change. When clients were asked repeatedly whether they wanted to proceed further, it was with sincere readiness to shift gears. Regularly, clients are informed that EMDR is no panacea, and a change in direction can occur if EMDR does not work for them. Reducing the so-called demand characteristics in good faith seems to resonate with military clients that the only real agenda of the therapist is their health and well-being.

CASE STUDY: CLIENT PREPARATION FOR CHRONIC WAR STRESS INJURY

We have already mentioned most of what is covered in Phase Two. After elaborating upon the specific components of client preparation for EMDR, our discussion will turn to examining military-specific applications.

Psychoeducation of Traumatic Stress Injuries

Most therapists are familiar with the need to educate their clients about their diagnosis, practical ways to cope or reduce their symptoms, and items to avoid that can worsen their condition and/or response to treatment—this is especially the case with war stress/traumatic stress injuries. Education can help establish the credibility of the therapist and make treatment seem immediately helpful to the patient, and help prepare the patient for next steps in treatment should continue throughout PTSD treatment, sometimes in brief discussions. Clients should be educated of available support services and during and after their course of treatment. For clients experiencing relationship, or grief issues, education about pastoral care through the chaplain’s office, or family counseling support programs can be useful to address the whole person. Military culture does not attach any stigma to speaking with a chaplain although some military members may be reluctant to seek mental health assistance. Education from military chaplains may reduce barriers to care. Similarly, there are dieticians and personal exercise trainers through the base health clinics or Morale Welfare and Recreation (MWR) including yoga and other meditative activities.

The DVA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Post-Traumatic Stress (2010) makes the following recommendations regarding military client education: (a) Teach the client to label, recognize, and understand PTSD symptoms (and other trauma-related problems) that they are experiencing; (b) Discuss the potential consequences of further exposure to traumatic stress; (c) Discussion of the adaptive nature of many of the symptoms, which have to do with survival and the body’s normal responses to threat; (d) Review practical ways of coping with traumatic stress symptoms; (e) Inform about co-morbidity with other medical health concerns; (f) Provide simple advice regarding coping (such as sleep hygiene instruction), explain what can be done to facilitate recovery, and describe treatment options; (g) Help the client identify and label the reactions they are experiencing; (h) Teach the client to recognize that emotional and physical reactions are expected after trauma, understand how the body’s response to trauma includes many of the symptoms of PTSD, and understand that anxiety and distress are often “triggered” by reminders of the traumatic experience that can include sights, sounds, or smells associated with the trauma, physical sensations (e.g., heart pounding), or behaviors of other people; (i) Teach ways of coping with their PTSD symptoms in order to minimize their impact on functioning and quality of life; (j) Help the client distinguish between positive and negative coping actions. Positive coping includes actions that help to reduce anxiety, lessen other distressing reactions, and improve the situation. They include relaxation methods (e.g., Tactical/Combat breathing, yoga), physical exercise in moderation, talking to another person for support, positive distracting activities, and active participation in treatment; (k) Advise the client to avoid negative coping methods may help to perpetuate problems and can include continual avoidance of thinking about the trauma, use of alcohol or drugs, excessive caffeine and nicotine or other stimulant, social isolation, and aggressive or violent actions; (l) Examine whether clients have unrealistic or inaccurate expectations of recovery and may benefit from understanding that recovery is an ongoing daily gradual process (e.g., it doesn’t happen through sudden insight or “cure”) and that healing doesn’t mean forgetting about the trauma or having no emotional pain when thinking about it; and (m) Explain and encourage discussion of treatment options, including evidence-based treatments.

Treatment Informed Consent

Shapiro (2001) describes several considerations for the therapist in regards to discharging the ethical duty to inform clients of the potential treatment risks and benefits associated with EMDR. However, before discussing risks related to EMDR, we need to back-up a step. After completing the clinical intake, therapists will usually provide the client feedback as to the assessment results including diagnostic impression and treatment recommendations. Included in that interchange should be an overview of all appropriate treatment options (including no treatment), so clients can truly make an “informed” choice. In the case of diagnosing a traumatic stress injury like PTSD, how does one properly inform clients about the range of treatment options, including EMDR?

Informing Clients of Treatment Options

In the case of a diagnosed war or traumatic stress injury, we advocate having copies available of the most recent (2010) DVA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Post-Traumatic Stress. The guideline has a summary that can be photocopied and handed to clients during the feedback session. EMDR is listed among the “A-level” evidence-based treatments, meaning those with the highest level of efficacy established via randomized controlled trials. The guidelines also say that every A-level treatment is roughly equivalent to the others, and there is insufficient evidence to indicate the benefit of contraindication to combining medication and psychotherapy over only one of the two approaches (DVA/DoD, 2010). Client preferences and the particular evidence-based treatments that the therapist has the most training and expertise with usually determine the initial treatment choice. Although every session will be different, here is one way to provide clients and informed overview of treatment options.

Nine times out of ten, maybe ten of ten, military clients will opt for a trial of that weird sounding thing. There is an effort, maybe not fully reflected above, to be above board when discussing other treatment options, as it is the client’s choice. That said, if one is being honest, then you have to bring up the requirements for repetitive exposure, daily homework, and degree of personal disclosure of mainstream cognitive-behavioral therapy, and conversely, mention that EMDR is different in that respect and more. In any event, the take-away is to make a good faith effort to inform clients of their treatment options.

Informed Consent Specific to EMDR Treatment

Here are the standard teaching points for obtaining client consent to EMDR, or, for that matter, any trauma-focused therapy, as none of the cautions is unique to EMDR: (a) Potential changes in memory and emotion related to EMDR in legal testimony, (b) High level of emotion and/or unexpected memories may occur while processing, (c) Appropriate safeguards are in place in case substance abuse history is reactivated by EMDR, and (d) Cautions about reliability of memory—meaning that not everything in our memory networks is necessarily factual. Dreams, movies, and fantasies can be merged with other memories and information is stored “as if” it happened, but it may not have. This is related to broader concerns over suggestibility and recovered child abuse or other trauma. Case in point, the author (Mark Russell) was using EMDR with a civilian client who had memories of alien abduction, once we reprocessed that trauma, and a few others, the presenting complaint involving a bridge phobia resolved. Therapists are not the memory police.

Additional items that should be covered with EMDR informed consent to protect both clients and therapists alike include: (a) Use of modified EMDR protocols are not evidence-based, and therapists should inform clients if they are modifying the standard EMDR protocol and that those variations have not been shown empirically to work; (b) Clients with active suicidal or homicidal ideation should be assessed for dangerousness and postpone EMDR until they are more stable. EMDR reprocessing or other trauma-focused therapy should not be conducted with clients with active, serious suicidal or homicidal ideation as it could exacerbate client level of distress; (c) Clients with a serious, life-threatening medical condition should inform their therapist and physician and get medical clearance for certain unstable conditions such as malignant hypertension, recent stroke, recent heart attack, etc. Clients should be informed that trauma-focused therapies including EMDR may cause a rise in blood pressure, heart-rate, and other stress-related response that could exacerbate a serious, unstable medical condition; (d) Clients who are pregnant should inform their therapist and physician before undergoing trauma-focused therapy including EMDR—this is especially true for clients experiencing complicated pregnancy, have a history of miscarriage, underweight, or premature deliveries. Clients in the final trimester should consider postponing EMDR therapy unless doing so presents greater risk. Consultation with the client’s physician should occur if any questions or concerns arise; and (e) Disclosure of a crime—clients should be informed during the review of limits of confidentiality that certain client disclosures such as perpetrating child abuse, elder abuse, or committing a serious infraction against the UCMJ (Uniformed Code of Military Justice) may have to be reported by the therapist, who is a mandatory reporter. Military mental health providers are also military officers, and under some circumstances, may be obligated to breach client confidentiality. Therapists should consult an attorney or JAG.

EXPLAINING THE AIP MODEL

Explanation of the EMDR theory and method is dependent upon the age, background, experience, and sophistication of client. Preparation of clients for EMDR includes a description of the AIP model such as the following: “Often, when something traumatic happens, it seems to get locked in the nervous system with the original picture, sounds, thoughts, feelings, and so on. Since the experience is locked there, it continues to be triggered whenever a reminder comes up. It can be the basis for a lot of discomfort and sometimes a lot of negative emotions, such as fear and helplessness that we can’t seem to control. These are really the emotions connected with the old experience that are being triggered. The eye movements we use in EMDR seem to unlock the nervous system and allow your brain to process the experience. That may be what is happening in REM, or dream sleep: The eye movements may be involved in processing the unconscious material. The important thing to remember is that it is your own brain that will be doing the healing and that you are the one in control” (Shapiro, 2001, pp. 123–124).

Clarifying Client and Therapist Role Expectations

The standard EMDR description of the client’s expectations goes something like this:

What we will be doing is a simple check on what you are experiencing. I need to know from you what is going on with as clear feedback as possible. Sometimes things will change and sometimes they won’t. I’ll ask you how you feel from 0 to 10—sometimes it will change and sometimes it won’t. I may ask if something else comes up—sometimes it will and sometimes it won’t. There are no “supposed to’s” in this process. So, just give as accurate feedback as you can as to what’s happening without judging whether it should be happening or not. Just let whatever happens happen. We’ll do the eye movement for a while and then we’ll talk about it. (Note. Includes material copyrighted by Francine Shapiro, Ph.D., and the EMDR Institute; used with permission.)

Another way of explaining the client’s role is:

All I need is for you to tell me the truth about what you are experiencing. I don’t need to know all the details; that’s up to you to decide how much to tell me, but, at a minimum, we need your honest feedback if things or changing or not. Please don’t try to force yourself to concentrate on a certain memory, picture, or whatever; just be an observer, and notice whatever it is that comes. Just notice it. Remember you’ve got the controls, so if you want me to stop, you’re the boss.

Demonstrating the Mechanics of EMDR

After arranging the chairs in the classic “ships passing in the night” arrangement (Shapiro, 2001), the therapist also introduces bilateral stimulation (BLS) to clients. For eye movements, the therapist collaborates with the client to determine the comfortable distance and direction of eye movement by asking “Where does it feel most comfortable to have my hand?” Distance from the visual stimulus to the client should not be so great (more than four feet) where the client’s visual field is occupied by background distractions.

Bilateral stimulation using eye movements: (a) Using the therapist’s hand or a wand; (b) Start with the therapist’s hand in the center of the face; (c) Slowly move laterally, side-by-side, and remind the client to track only with his or her eyes; (d) Speed up the hand movements until the client is unable to track; (e) The therapist can test out diagonal (left to upper right) movements; (f) Vertical eye movement is anecdotally reportedly as helpful for dizziness or vertigo; and (g) When using Neurotek devices and visual tracking initiate slow frequency and speed up to find upper limit of client tracking. Most clients prefer and respond best to the faster BLS rate.

Bilateral stimulation using auditory sounds: (a) Alternating snapping fingers—although it’s demonstrated in EMDR trainings that snapping fingers on alternate sides of the client’s head works—it does not, especially for any length of time. Moreover, it looks really tacky; and (b) Neurotek devices and headphones—much better. The author (Mark Russell) has had good success with the headphones and alternating sounds. Adolescents and young adults seem to prefer the headphones for some reason. Also, combining the auditory and other stimuli can be effective.

Bilateral stimulation using kinesthetic vibrations or taps: (a) Different variations of bilateral kinesthetic stimuli have been reported; (b) Alternating finger taps was the first, when it was used as a control group for testing the effects of eye movements in one of the first DVA random clinical trials on EMDR. At the time, only eye movements and alternating finger snapping were taught; (c) Alternating taping—Priscilla Marquis on a trip to Central America was working with blind survivors of land mines. Eye movements were not feasible, so she had clients hold out their hands and she tapped alternately either the hand or knee; (d) “Butterfly hug” was almost not included because the image of a group of Marines being instructed to give themselves butterfly hugs just did not sit right. Still some research with children after a natural disaster reported it was effective and some hardcore GIs may have fun with it; and (e) Use of Neurotek device and alternating vibration pads is the preferred method. Clients hold onto pads in their hands that generating vibration sensations.

Combining bilateral stimulation. The author (Mark Russell) has on numerous occasions chosen to combine visual and auditory bilateral stimulation with generally good effects. An indicator for considering combining stimuli is when the client appears to be “looping” and/or under-responding to one or the other. Only future research will illuminate for certain, but if clients are not responding to one, rather than switch outright, the therapist might check for an additive effect. The idea of introducing a third type of stimuli (kinesthetic) is intriguing, but no experience to back it up. Preparing clients for the possibility of dual-forms of BLS is helpful.

ESTABLISHING THE THERAPEUTIC FRAME

Jerome and Julia Frank’s (1991) classic Persuasion and Healing spoke about the history of healing rituals across human civilizations. According to Frank and Frank (1991), the healing setting is often adorned with cultural artifacts that reinforce the status of the healer in society. We have bookshelves filled with impressive sounding book titles and the walls, desktops, and file cabinets reinforce our credentials as healers, as do our professional titles, Doctor, Counselor, Therapist, and Social Worker. The Franks (1991) also describe how restricting public access to healers has always served to reinforce the value of the healer’s services. The notion of a therapeutic, healing frame is particularly meaningful within the warrior class. However, cultural and institutional stigma and barriers to mental health care have left a deep-seated mistrust of traditional psychotherapy in the military.

Practitioners working with military populations may want to take an objective look at their therapeutic frame, particularly in light of the value placed on authority, credibility, and accomplishment. That said, the author (Mark Russell) always kept children’s toys and crayon-drawn pictures strewn across his office that were usually met with cautious, skeptical expressions by military visitors. However, several other cultural artifacts were also within eye’s grasp: a model of the human brain; blown-up pictures of neuroimaging from Lansing, Amen, Hanks, and Rudy’s (2005) study of six police officers diagnosed with PTSD, demonstrating visible pre- and post-changes in brain functioning via SPECT scans; and a Neurotek device that raises everyone’s curiosity. Leeds (2009) aptly entitled a section under client preparation as “Seeing is Believing”—Brain Images of PTSD Patients Before and After Treatment (p. 104). He even mentioned Lansing et al.’s (2005) study, and military personnel ears perk up when it’s revealed that this psychology research was with six police officers, a paramilitary organization whose employees are no strangers to occupational hazards like their warrior cousins.

As kooky as EMDR might sound, when introducing it to hard-nosed, battle-tested warriors, there is an instinctual appeal, which is what may have attracted me to EMDR. Nearly a dozen neuroimaging and neurophysiological studies have been published to date, the majority being case studies, but sufficient to exclude chance findings. Framing EMDR in neuropsychological terms has instant credibility for many warriors, and the Neurotek serves to reinforce that this is a very different kind of mental healthcare—a new age form of healing. Therapists are advised to pay attention to their therapeutic frame when preparing clients for EMDR. In doing so, it may be helpful for therapists to consider that by establishing the conditions for therapeutic change, including building of a therapeutic alliance and therapeutic frame, all serve to strengthen associations on a neurobiological level between the client’s maladaptive and adaptive neural networks. Increasing client access to, and activation of their adaptive neural networks, has the converse effect of reducing the predominance of pathogenic memories.

Introducing Metaphor for Expected Client Role During Reprocessing

Shapiro (2001) and Leeds (2009) both utilize a train metaphor to describe “mindful noticing” whereby clients are instructed to recall looking out of a train and watching the scenery go bye. For many of us, this is a powerful metaphor. Increasingly, however, younger generations, at least in the U.S., do not have the experience of riding in a train. They could imagine what it would be like, but it would not likely be as strong an experience then those who had. Consequently, with younger cohorts, using the metaphor of looking out of the window of a car will unquestionably be an experience they can relate to.

Why introduce treatment metaphors now? The purpose of going over metaphors at this juncture is that the therapist wants to “front-load” certain information for clients during the relatively non-stressed context of preparation to avoid unnecessary overloading clients with new information during intense reprocessing. By facilitating the development of a therapeutic alliance and discussing metaphors, stop signals, role expectations, and the like, the therapist is in essence creating an adaptive neural network relating the conditions of therapeutic change and EMDR to the maladaptive neural network. Appreciating that memory systems have evolved for the primary purpose of helping us understand, predict, and control our life experiences and behavior in an adaptive fashion informs us why such front-loading can be beneficial.

The Stop Signal and Metaphor for Reprocessing

Clients are routinely asked to identify a non-verbal way to communicate their desire that the therapist cease with the bilateral stimulation. Often, the author (Mark Russell) just advises clients to raise their hand and say “stop” if they are “wanting” (versus “needing”) to stop. Where possible, it can help reduce the sense of threat from vulnerability that military clients may experience by just being in the mental health space. Be mindful of phrases like PTSD (“PTS”), therapy (“strategy”), needing (“wanting”), or patient (“client,” or refer by rank) that might have negative connotations for some personnel, particular senior enlisted and officers.

The “Break and Gas Pedal” Metaphor

Since most adults of whatever cohort have had the experience of driving a vehicle, the use of the “Break and Gas Pedal” metaphor consistently serves well. After soliciting the client’s “stop signal,” the Break and Gas Pedal metaphor is introduced, and will assuredly be used again during reprocessing. The client is told that when we start using EMDR, they are in the driver’s seat. The break is their stop signal, and the bilateral stimulation is the gas pedal. Clients are advised that by keeping their foot on the gas pedal they will get us to our destination quicker, and conversely, using the break will slow our arrival. Nevertheless, all cars have a break and gas pedal for a reason, so clients can use them as they see fit. Therapists using this metaphor will find it useful to remind clients of this frequently especially those who want to verbally process their experiences, sometimes for lengthy periods. There are conceivable reasons why clients would choose to do so, and we should respect their desire. But when stopping and talking, and more talking becomes the norm, one way to reset the norm is to remind them of the gas pedal. If the pattern continues, therapists will need to assess for a possible blocking belief (see Chapter 9, this volume).

Length and Pace of EMDR Treatment Sessions

Shapiro (2001) has recommended 90-minute EMDR sessions from the beginning, which is still taught as the preferred meeting duration in order to ensure sufficient time to complete reprocessing. However in many healthcare settings, particularly managed-care and the military, providers often do not have the liberty, nor might it be feasible if they did, to utilize the extended session format. Fortunately, a large, well-controlled study on EMDR in a managed-care setting has been conducted. For example, Marcus, Marquis, and Sakai (1997) compared 67 adult clients diagnosed with PTSD who received either 50-minute individual EMDR, psychodynamic, cognitive, or behavioral therapy or group therapy at Kaiser Permanente Hospital. The results demonstrated not only that EMDR can be implemented effectively within a standard 50-minute therapy format, but that clients receiving EMDR reported significantly lower symptoms of PTSD, depression, and anxiety than clients from the other treatment groups on average of 6.5 sessions versus 11.8 sessions. Moreover, 100% of single trauma and 77% of EMDR clients no longer met diagnostic criteria with most treatment gains maintained at six-month follow-up (Marcus, Marquis, & Sakai, 2004).

Pacing of EMDR Sessions: Weekly and Consecutive Meetings

In the ideal therapy world, treatment sessions would occur on a regularly scheduled weekly basis until concluded. That may work in strictly controlled laboratory settings to evaluate treatment efficacy and perhaps other clinical environments, however in the military environment a lot can transpire that makes weekly meetings a fantasy. For example, military personnel are often not the masters of their time, and, due to stigma and concerns over repercussions, are often reluctant to press their work center supervisors to grant time away from their military duties to attend weekly counseling sessions. Moreover, military personnel and sometimes their therapists may have high work demands and are frequently on the move, attending to mandatory trainings, annual inspections, after-hour watches, and deployment preparations, that can result in multiple cancellations and rescheduling. Specialized treatment programs for war stress injuries like The Soldier Center may receive military clients under orders to complete treatment, and thus can offer EMDR on a weekly or even consecutive day basis. Published accounts of consecutive-day treatment with EMDR in the military exist (e.g., Wesson & Gould, 2009) and should be strongly considered when military clients have “dwell” time or extended periods of relative inactivity. However, this is not the norm and reinforces the need for therapist and clients to proceed as safely and efficiently as possible. Therefore therapists and clients need to discuss the frequency of the meetings and collaborate on identifying the most opportune meeting day and times that pose the least risk for disruption. Ideally, any therapy including EMDR, appears to work best with a mutual sense of continuity that weekly sessions provide. That said, the author (Mark Russell) has had to adapt to “every other week” or even less regular EMDR sessions. We can do the best we can. Therapists need to reconcile that, in most circumstances, clinical practice in the military will usually be less than optimal. When that is the case, we look to the Marine Corps motto of “adapt and overcome.”

COPING STRATEGIES FOR REPROCESSING PHASES

Shapiro (2001) added coping skills strategies like a safe/calm place exercise to be used to prepared clients for EMDR reprocessing, particularly when an incomplete sessions occurs and the therapist believes that the client needs support in making the transition from reprocessing distressing material to re-entering the outside world after the session ends. Conducting the safe/calm place exercise with clients during the preparation phase provides an opportunity for therapists to gradually introduce the idea of dual-focused attention and bilateral stimulation to clients, with hopefully a positive outcome, to reduce anticipatory anxiety. In terms of the AIP model, the therapist is attempting to access the client’s adaptive neural (memory) networks where our past secure attachments, achievements, mastery, coping, and other “positive” affect-laden experiences are physiologically linked and stored. The exercise itself is a form of guided imagery that has been a staple in behavioral therapy for years. However, adding short sets of bilateral stimulation to the relaxing images and cue words is a new twist. Conceptually, the bilateral stimulation is intended to strengthen the positive and relaxing associations. It is not clear, however, that the addition of eye movements causes any greater enhancement effect than traditional guided imagery whereby the therapist induces heightened relaxation through their verbal discourse. Just as in standard relaxation training, some clients may experience a Relaxation Induced Panic (RIP), whereby the relaxed state triggers an intense sympathetic stress response, or others may experience negative versus positive associations during the exercise depending on their selected place (e.g., bedroom). In the later circumstance, clients are simply instructed to select a more neutral safe or calm place. Otherwise the therapist might switch to another form of stress management activity, or use RDI that we will cover shortly. The reader is referred to Shapiro (2001) for the safe/calm place exercise that has become standard part of EMDR trainings. Another effective and perhaps more familiar stress reduction technique in the military is what some military and police agencies refer to as “Combat” or “Tactical” Breathing, which is described below, as are “grounding techniques” that therapists may want to teach their clients who present with high levels of dissociation.

RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT AND INSTALLATION

Resource Development and Installation (RDI) was developed by Korn and Leeds (2002) as a means to enhance or strengthen the client’s access to internal “resources” associated with their adaptive neural networks. Having supervised or consulted with numerous recently trained therapists in EMDR, a trend has emerged whereby RDI is the preferred, and sometimes the only intervention, for clients with stress injuries. Most of us were quite nervous about using EMDR outside of the training comfort zone, and, before RDI, the option was to jump in the water or go to the park instead. To be certain, when used appropriately and for the right reasons, RDI is an effective tool. However, most clients do not need RDI, and using RDI will not address the issue that led to clients seeking help.

Leeds (2009), the innovator of RDI, offers sage advice that we concur with: “When patients are clearly suffering from symptoms of PTSD and meet readiness criteria, there are several invalid reasons to use RDI before standard EMDR reprocessing” (p. 121): (a) The therapist may have a vague or uneasy sense that the client is too frail or unstable; (b) the therapist is concerned about the client’s intense emotional experience or abreaction; (c) the therapist is uncomfortable or fears they cannot handle the content of the client’s memories; (d) the therapist has a preference for wanting their client to “feel good”; and (e) the therapist fears they do not have enough time to complete reprocessing. It has become somewhat EMDR lore that a certain subgroup of clients that meet criteria for a developmental traumatic stress disorder like complex PTSD or Borderline Personality Disorder will almost universally require RDI before EMDR reprocessing. Yet less than 5% of adult clients with PTSD, even with child-onset PTSD, were reported to need RDI in a large controlled study, and those who received RDI, needed only one session before EMDR reprocessing (Korn et al., 2004, cited in Leeds, 2009). Of course, there are also many clients without complex PTSD or Borderline traits that can benefit from RDI. The safest bet, of course, is to ensure that the treatment plan fits the person, not the diagnosis, or the therapist’s needs.

Why might delaying EMDR reprocessing matter? On average, therapists may have a limited opportunity to work with military personnel and make a real difference, that’s the reality. Service members who brave the stigma and barriers to care and risk their military careers to seek help need and deserve the best we can offer. If RDI is clinically and/or operationally indicated, then it should be offered. However, most clients will not differentiate between EMDR, RDI, and any of the other modified approaches. If RDI is all they got, and their war stress injury has not been helped, then EMDR would have failed, not RDI. Remember, the only evidence-based treatment is standard EMDR protocol. In sum, practitioners should use RDI and other EMDR variants very judiciously, and only when it is clinically and/or operationally in the best interest of the client.

COMBAT/TACTICAL BREATHING

Law enforcement and the military regularly include martial arts training and what is referred to as “Combat or Tactical Breathing,” a simple, but effective controlled breathing technique that has been used by warriors for centuries to rapidly gain control over the body’s acute stress response and adrenaline rush (sympathetic nervous system) even in extreme, high stress, and hostile environments. Tactical/Combat Breathing in civilian parlance is often referred to as “Deep,” “Diaphragmatic,” “Lamaze,” or “Autogenic” breathing. LTCOL David Grossman’s (2007) On Combat describes how he trains police officers, surgeons, and Army Green Beret to effectively use Combat/Tactical Breathing as a means to quickly calm themselves by activating the parasympathetic nervous system and de-linking the intense physiological response from the memory of the recent event. Like any skill, clients are encouraged to practice as regularly as possible and to use Combat/Tactical Breathing before, during, and after combat or other operational missions.

Combat/Tactical Breathing Steps

Four-Count Method

1. Breathe in through your nose with a slow count of four (two, three, four)

2. (Therapists may request clients place their hand on their stomach to see if they are properly filling the diaphragm with air, as evident when their stomach and hand rise)

3. Hold your breath for a slow count of four (hold, two, three, four)

4. Exhale through your mouth for a count of four until all the air is out (two, three, four)

5. (Client’s hand should lower as their stomach lowers)

6. Hold empty for a count of four (hold, two, three, four)

7. Then repeat the cycle three times

Reprocessing Acute Dissociative States

Dissociation can be a common component in many war and traumatic stress injuries and is usually reprocessed like other adaptive reactions associated with the flight/fight/freeze response. EMDR reprocessing, like any trauma-focused approach, can be emotionally intense and result in either accessing or generating a dissociative response during session. In some rare cases (at least from the author’s [Mark Russell] experience in the military) a client’s attentional focus may significantly constrict and become excessively self-absorbed and non-responsive to the external environment. In-session, clients may stare blankly ahead or what’s referred to as the “1,000 yard stare.” In this detached, dissociated state, client’s attentional focus is generally too self-absorbed to maintain dual-focused attention; therefore EMDR reprocessing is shut down. It is natural, and to be expected, that traumatized clients will report and/or exhibit dissociative symptoms during reprocessing, especially those with notable history of childhood trauma. These are typically transient states like other emotional conditions that therapists observe during reprocessing (e.g., fear, terror, anger, grief, rage, pain, etc.). In the majority of cases, the dissociative symptoms will spontaneously resolve through the combined effects of dual-focus attention and bilateral stimulation.

It is critical for the therapist to understand the AIP model, particularly in relation to dual-focused attention, dissociation, and reprocessing. The majority, if not all, psychopathological states arise from maladaptive neural networks that can be characterized as excessively self-focused or self-absorbed conditions, with strong emotionally negative valence (see Nasby & Russell, 1997; Russell, 1992). In common terms, depression arises out of “depressogenic schemas” (e.g., Beck et al., 1979) and anxiety disorders are said to be a reflection of “fear structures” (Foa & Kozak, 1986). The maladaptive neural networks, when activated, tend to dominate our attentional focus resulting in a highly selective, negative attention and thus interpretation of past, current, and future events. The selective negative bias reinforces the habitual cognitive, emotional, behavior, and physiological responses that maintain an imbalanced, maladaptive condition. To be effective, EMDR requires both dual focused attention and bilateral stimulation, a vital point that many seem to overlook as fascination turns to the eye movements. We generally do not ask clients to close their eyes during reprocessing because it’s harder to detect whether clients are maintaining a dual-focused attention. Standard EMDR protocol asserts that when therapist observes their client stop-tracking the bilateral stimulation, they respond with a verbal and/or non-verbal prompt to maintain that dual focus (e.g., therapist wiggles their fingers and says, “ok keep tracking!”). This is also why therapists are strongly advised to maintain verbal contact with their clients, particularly during intense reprocessing. The sound of the therapist’s voice serves to split-away the client’s awareness from internal preoccupation to perceive stimuli of threat, pain, and terror, to a joint internal and external focus, that allows access to other neutral, positive, or more adaptive perceptions from the here-and-now—it’s this dual-focus awareness that frees up our cognitive capacity to attend to reprocessing information in a more adaptive direction. If the therapist is adhering to the standard protocol and their clients appear “stuck” in an dissociative state that interferes with reprocessing, then therapists can shift gears and utilize one of many “grounding techniques.” These techniques, in effect, are designed to restore the balance of the client’s self-focus by re-engaging their attention or awareness to external sight, sounds, and physical sensations from the outer environment, including their physical body. Some authors have developed specific exercises to reduce the dissociative response (e.g., Leeds, 2009).

Grounding Activities for Dissociative States

In general, however, any instruction to re-direct the client’s attention to a present-oriented focus to the outer world will have a “grounding” effect. Here are some others: (a) Therapists should use a normal, firm, audible, and matter of fact speech tone to increase the client’s alertness; (b) Ask clients to rate (e.g., 0–10) their perceived degree of dissociation, or how loud they hear a certain sound, or how vivid the color of a specific object is in the office; (c) Avoid mirroring the client’s low affective tone by using slow, soft, low audible speech tones that may reinforce a dissociative detachment; (d) Direct the client’s attention to their hands gripping the arm of a chair, the texture of the chair or sofa, the physical sensations of their feet touching the floor; (e) Turn on a radio or music player, ask them to rate how much they like the song; (f) Direct the client’s attention to environment cues such as their reporting the time on the clock or on their watch, or attend to environment sounds (e.g., cars passing bye, the fan, music, etc.); (g) Direct the client’s attention to scan the environment for specific objects (e.g., can you see the statue on my desk, please describe it to me, what color is it?); (h) The therapist can hand clients a cup of water and ask them to sip, and pay attention to the sensations in the mouth and throat; (i) The therapist can try ERP discussed earlier in this chapter; and (j) The therapist should keep in mind, to not panic or sound overly fretful, or otherwise convey a sense of fear or threat to the client. The disconnected state will end—and most very rapidly. If, for whatever reason, the client remains in the dissociative state, then activate the medical emergency response system.

Summary on Stress Reduction Techniques in the Military

One final note on the use of stress reduction techniques, the author (Mark Russell) has rarely utilized any stress management or coping skill exercises with military populations in conjunction with EMDR, with the exception of one to two clients where we did deep breathing exercise (now called “combat/tactical breathing” by the Army). During the basic EMDR trainings, participants are taught the safe/calm place exercise and RDI, and many other clinicians working with the military may have used these approaches religiously, so this is only one person’s opinion. However, with a treatment sample in the hundreds, reliance upon a stress reduction technique for transitioning purposes rarely has been warranted. Therefore, the author (Mark Russell) generally leaves it out of the preparation phase, unless the client demonstrates he or she are poor at self-regulation during the history taking. On an aside, adopting common cognitive-behavioral stress reduction techniques into the standard EMDR protocol may have made sense conceptually, and has been proven clinically useful in certain cases, but the net effect has been a clouding of the distinction between EMDR and CBT.

Addressing Military Client Treatment Concerns and Fears

Ambivalence in clients consenting to mental healthcare occurs frequently, however in military populations it’s the norm. Whether it’s trepidation about the inherent negative bias and stigma associated with seeking mental health services in the military, fears around repercussions on promotion and career, or the service member’s instinctual motivation to avoid the threat of reopening wounds of inescapable pain, there are legitimate reasons for ambivalence that the therapist must address at the outset. Some of the predictable barriers to care such as confidentiality or potential implications of the client’s diagnosis and treatment on their ability to deploy, or remain on active-duty, would have been addressed at the initial clinic visit and informed consent proceedings. However, during client preparation and education specific to EMDR treatment, new concerns may arise, and merge with other lingering worries or confusion that can fuel an ambivalent state-of-mind. Not being upfront and discussing the elephant in the room, breeds an undercurrent of mistrust that will likely derail the best laid plans. The eight-phase EMDR protocol has built-in a series of checkpoints for therapist to solicit client feedback on the status of their knowledge and experience before moving onward. At the end of the preparation phase, we want to explicitly inquire about the status of the client’s understanding and motivation toward EMDR therapy, and any potential barriers that may impact the trajectory of treatment. So what are the common reservations many military members may harbor, and how might a therapist work through it?—this is the final section of the preparation phase.

THE AMBIVALENT MILITARY CLIENT

Like all clients, military personnel maybe ambivalent around the process and outcome of EMDR (Shapiro, 2001). Concerns over the process may pertain to the degree of safety, trust, and rapport developed in the therapeutic relationship. A general uneasiness that may be expressed as repeated confusion of questioning about certain aspects of the protocol or timing of the treatment (e.g., may report feeling rushed, needing more time, etc.), or the confidentiality of treatment, and maybe the desire to postpone for another day. The therapist non-defensively should attempt to answer the client’s questions, and give them the benefit of the doubt. Sometimes questions may be asked that are not challenges to the therapist or relationship, but reflect a knowledge gap, understandable given the context and amount of information clients are bombarded with, and the fact that they are not as familiar with EMDR or mental healthcare as the therapist. Unresolved concerns about confidentiality and informed consent to treatment need to be satisfactorily addressed before therapy can proceed.

The Coerced Mental Health Seeking Client

It is not uncommon for military personnel to show up to a mental health appointment, kicking and screaming. For a few it may be a public display to save face, for others the therapist will have no problem recognizing. When asked what brought them into the clinic today? The client will make it crystal clear for the therapist that it wasn’t their idea. If not their wife or husband, the next likely culprit is the client’s “Command.” This may be a formal consequence of a disciplinary action, or proactive urgings by a leader in the client’s chain-of-command, in either case, usually there is a threat of a break-up, marital separation or divorce, or a command suspending discipline in lieu of the client’s getting help. Other scenarios are possible too, but the main point is that the client’s reluctance to engage in therapy is in part because they are not here by their free will, and probably believe that they are being treated unjustly. Nevertheless, the therapist can sympathize with the client over his or her predicament, but indicate that treatment will not be effective, and in fact could make things worse, if the client is not ready, willing, and able. Some clients will say whatever it takes to appease the therapist so that treatment can proceed and they can get their family member, friend, or command off their back. Others may be interested in engaging the therapist in a discussion of the possible benefits of the time spent in the therapy office. However, if the therapist has reservations about the client’s level of free will to consent without undue pressure or coercion, they should not use EMDR.

During the client history and preparation phases, the therapist should be mindful of the client’s verbal and non-verbal communications suggesting either concern or confusion over the information that is being shared by the therapist. Clarifying the client’s questions and concerns at the time they arise, can help avoid having to backtrack later on. It is always good practice to check the client’s understanding and anticipate questions not expressed before moving forward. However, when questions, confusion, and postponements arise or persist, it can also signify client fears and concerns over treatment outcome in general and EMDR specifically. When known or identifiable, these too must be confronted and resolved before treatment can ensue.

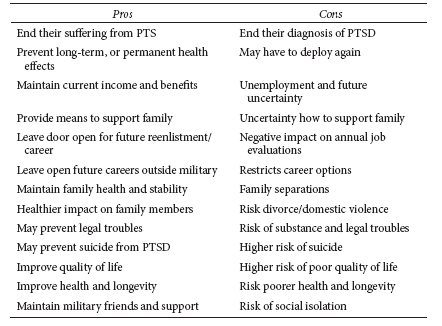

Issues of Secondary Gain

For instance, in Phase One, we identified possible secondary gain issues and might ask, “What would be the potential downside, or negative effect you might experience if you PTS was completely over?” The therapist should anticipate and not accept the client’s first response, which is almost always “There is no downside.” If that indeed is the client’s response, the therapist may want to say something like, “Yeah I understand that, but I also know that most people do report that while they are relieved not to have PTS anymore, they experienced some negative consequence as well.” The client may ask “Like what?” and the therapist can mention a few like having to go back on deployment, separations from family, or losing a possible disability pension. Observe the client’s reactions. More often than not, clients will forcefully, and sincerely express their choice to be relieved of PTS over any of the other considerations. Others may say the right things, but harbor secondary gain, and the therapist may never know the difference. If potential or actual secondary gain are disclosed by the client that signifies a reluctance to get better (e.g., want to leave the military, benefit from a legal settlement, do not want to deploy), then the therapist must exit EMDR mode, debrief or counsel the client about their options, and recommend they speak with their chaplain. A twist would be a client with war stress injury, who genuinely wants help, but is ambivalent for the secondary gain. The therapist can help the client explicitly identify all the pros and cons of treating their PTS in the military, even if it meant a return to duty finding. See Table 6.1 for a list of some potential pros and cons for treating military personnel diagnosed with a war stress injuries in the military.

Table 6.1