cooking from the

asian

garden

Hanging side by side in my pantry are a cast-iron frying pan and a wok—both utensils blackened with use. When I set up housekeeping in the early 1960s, I had never seen a wok, but once I became familiar with it, I made it one of my best-used tools. Other Asian influences gradually found their way into my kitchen as well. Stir-frying ranks with soup at the top of my list of ways to prepare garden vegetables. Japanese noodles fried with cabbage, and carrots and chicken soup with chive dumplings and pac choi, are family favorites. In recent years, my constant exposure to Asian vegetables has led me to consider pac choi, bunching onions, fresh ginger, pea pods, and fresh coriander as reliable staples.

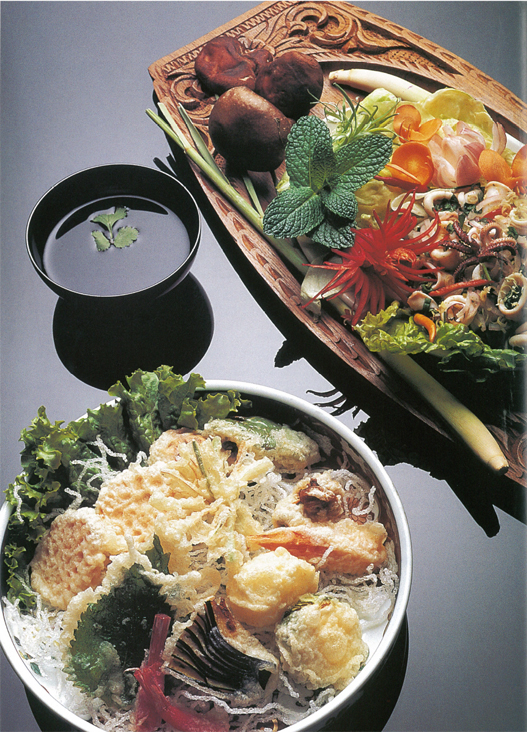

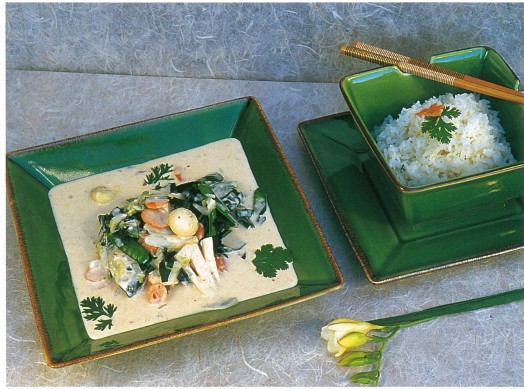

Tempura vegetables and a lovely Thai squid salad, filled with fresh herbs, are two great Asian dishes.

In introducing Asian cooking, it is important to point out that its day-to-day style differs quite sharply from what Americans generally think of as Asian fare. Consider that Asians rarely know how Americans really eat at home—they think we live on hamburgers and French fries and remain unaware of the corn on the cob and zucchini bread that enrich our lives and you start to sense how bound we are to stereotypes. I myself, who was raised on chop suey and bottled curry powder, for instance, was surprised to learn that these “Asian foods” were mere anglicized creations. Further, I discovered that even the Asian food we eat in restaurants distorts our view, as these dishes are first, tailored to American tastes, and second, represent Asian restaurant rather than home-style cooking.

The fact is, well-meaning Chinese chefs, wanting to please their guests, often use more meat and oil in the United States than they would in China. And because Asian vegetables often are either unavailable or unfamiliar to Americans, many Chinese chefs limit their use to just a few dishes, incorporating only some of their cabbage-family greens and none of the fresh ginger shoots or Chinese chives enjoyed in China. Japanese chefs here, who are usually unable to obtain a full array of Japanese herbs and, again, are catering to American tastes, tend to avoid using seaweed and daikon. Even recipes in most Asian cookbooks aimed at American cooks reflect this bias not only by including few vegetable dishes but by routinely substituting American vegetables for Asian ones in recipes.

Significantly, gardeners can view the food of Asia differently. We need not be limited by the supermarket or by the restaurateur’s hopes of pleasing a timid, habit-bound clientele. Rather, we have the luxury of exploring Asian cuisines by growing the vegetables and herbs native to them. Of course, a thorough summary of Asian vegetable cookery in the few pages available here is impossible. The subject is enormous, not only because of the many nationalities involved but also owing to the vastly different climates, from the tropics to the mountains, encompassed by the continent. Here, I focus on Chinese and Southeast Asian cooking. You will find some information on Japan, Korea, and India and summaries of their cooking styles, but Chinese, Thai, and Vietnamese food dominate because, of all Asian food cultures, they incorporate the greatest array of vegetables and herbs gardeners can grow and enjoy.

Though Asia has long supported vast populations, only a small part of the land supports agriculture. Out of necessity, then, Asian cooks have had to maximize the use of their food, energy, and water, and this need has led to many similarities among cuisines. For instance, oven cooking, which is fuel-intensive, is found in none of these countries. Grazing land is limited, so the flesh of large grazing animals is rarely used. Food itself is dear, so, when possible, all edible parts of both plants and animals are used. Until recently, the lack of refrigeration, too, forced a reliance on pickled and dried foods. Foods are pickled either by salt curing or in vinegar. At first taste, these vegetables can be too strong for Western palates, but within the context of Chinese cooking in general and, in particular, along with the often neutral components of a Japanese meal, they can provide an enjoyable tang.

Also common in much of Asia but foreign to most Westerners are dried foods such as shrimp and pac choi. These flavors might be compared to that of raisins in contrast to the flavor of fresh grapes; the original taste is intensified and altered in subtle ways. When you open a package of dried shrimp, the strong smell could discourage you but, once cooked and combined with other ingredients, the shrimp has quite a subtle taste. (For comparison’s sake, think of the strong flavor of dried Parmesan cheese when tasted alone.)

A discussion of Asian foods would be incomplete without coverage of their healthfulness. You are surely aware by now of the campaign against saturated fat and for fiber in the diet. In this regard, Asian cooking ranks high among cooking styles. The cooking oils are predominantly vegetable based, myriad vegetables make up a large part of most meals, and protein sources are lean, as in the case of tofu. So, unlike far too many of life’s pleasures, authentic Asian food is good for you.

Asian Cuisines

As Asia is so large and the cultures so varied, it helps to concentrate on a few of the cuisines in detail.

Chinese Cooking

Chinese cooking is a rich cuisine for the gardener-cook because many of the Chinese cooking techniques treat vegetables beautifully. Be warned, however: the range of ingredients and style in Chinese cooking is enormous. Cooks in northern China make dishes and use vegetables that their neighbors to the south have never heard of, and the opposite is true as well.

In China, food is one of the major components of the culture. In fact, discussing China’s cooking without considering the philosophical and medicinal aspects of the food is something like taking a diamond out of its setting: the stone is wonderful to look at, but its true potential is hard to experience. For thousands of years, Chinese poets and philosophers have expounded on foods and food preparation. Each holiday, each event in a person’s life, is associated with specific foods. But the cultural significance of food in China has long been matched by the minute attention paid to its nutritional properties. Food itself has always been treated as an integral part of personal health care. In fact, during some of the ancient dynasties, physicians who specialized in nutrition were among the highest-ranking doctors, and foods we now describe as high in vitamins and minerals were often prescribed for specific conditions—iron-rich foods following childbirth, for example.

Daily fare in China consists of rice served with vegetable-based dishes in which meat or seafood is used primarily as a seasoning. Thus, stir-fries of greens or beans might contain pork, chicken, or shrimp, but only in small amounts. There might be meat in the stock base of a braised vegetable dish or in a stew with vegetables.

Throughout most of China, the myriad members of the cabbage family are the primary vegetables. Also common is a wide variety of squash and beans. Ginger, garlic, and onions are the basic seasonings. The use of herbs is unusual, as these are considered medicinal, not culinary. But Chinese food draws intense flavors from dried mushrooms, seafood, and fruits; sauces made from seafood, beans, and fruits; pickled vegetables; and soy sauce. Many wheat breads and noodles are consumed in China, especially in northern areas, but rice is the predominant grain, and in much of China it is served at least once, in some form, every day.

Japanese Cooking

Limited agricultural soil and proximity to the ocean have greatly influenced the tastes of Japan. Japanese cuisine, elegant and highly stylized, is characterized by the use of dashi (a light bonita stock), a variety of braised and one-pot dishes, sea vegetables, a distinct scarcity of fats, and elegant presentation. While the Japanese enjoy many meat dishes, the primary proteins are some form of soybean and seafood. As to vegetables, a somewhat limited range is widely used in numerous variations. Most often, vegetables appear in braised dishes, served cold with a dressing of some sort, or as pickles, which in some of their many forms are served with practically every meal. Rice and noodles are the primary starches; seasonings include ginger and onion plus numerous herbs, some of which are native to Japan.

In Japan, as perhaps no other country, the visual presentation of the meal has the aesthetic value of high art. A simple, clear soup might be garnished with chrysanthemum petals or a perfect leaf of mitsuba. The love of nature is often expressed in this medium—with daikon carved in the shape of a crane, for example, or layers of onion shaped into a calla lily. Table settings, too, are carefully thought out. For instance, a simple plate might contain nothing but a few slices of crab-stuffed cucumber and a sprig of red perilla. Appreciating the appearance of the food is an integral part of enjoying a meal in Japan.

In the garden, American gardener-cooks can give themselves access to Japanese herbs, the versatile daikon, and Japanese-bred cucumbers and squash. And by viewing the garden through Japanese eyes, Americans can renew their appreciation for the seasonal nature of gardening.

Indian Cooking

Indian cooks are the world’s “flavorists.” Instead of boiled potatoes with butter, consider potatoes cooked with mustard seeds, ground cumin seeds, coriander, freshly grated ginger, red chilies, peanuts, and lemon juice—wonderful! Served with chapatis, an unleavened whole-wheat bread, and raita, a yogurt dish made with shredded cucumbers, this dish is close to heaven.

In many parts of India, the people are vegetarian; in others, they eat some meats and seafoods. Dahl—a loose term covering various legumes such as dried split peas and lentils—and milk products, including yogurt, are primary protein sources, particularly for the vegetarian segment of the population. Vegetables common in India include eggplants, potatoes, beans, carrots, cauliflower, okra, peas, and many kinds of dried legumes. The pancakelike chapati is served with most stewed dishes and soups. Rice, often mixed with spices and vegetables, is common throughout most of the country.

Southeast Asian Cooking

The foods of Southeast Asia are heavily influenced by their proximity to China and India, which means most meals include rice; stir-fries and flavorful curries are common, and recipes are commonly seasoned with coriander, ginger, shallots, and garlic. The primary protein sources are seafood and, in some countries, pork. In contrast to practice in China and India, most cultures use coconut milk in sauces, curries, and/or desserts, peanuts are often part of a flavoring paste, and fish sauces are a common seasoning. People in this part of the world, unlike in China, use numerous fragrant fresh herbs for seasoning, including lemon grass, lime leaf, basils, and mints. Spicy dishes filled with chilies are not unusual.

Of course, there are differences among the cuisines. For example, in Vietnam, once a French colony, baguettes are common and often filled with sliced meats, vegetables, and herbs. Thai cooks are famous for their intricately carved vegetables and complex curries, and Indonesians enjoy many sambals (fiery pastes and condiments with seasonings unique to some areas).

Ingredients

Purchase most of your ingredients in an Asian grocery store, in a natural-food store, or obtain them from mail-order sources. See the Resources section for more information.

Cooking Oils

Peanut oil and salad oils are used for frying. Sesame oil, with its string characteristic flavor, is used in China and Japan as a seasoning rather than a cooking oil and is usually added to the dish at the last moment. In India, vegetable oils and, occasionally, ghee (clarified butter) are used in many curries and vegetable dishes.

Dried Ingredients

Mushrooms are one of the most important dried ingredients in both Chinese and Japanese cooking; they impart their rich, musky flavor to many dishes. Dried shrimp, fish, seaweed, and pork flavor soups and stir-fries. Most dried ingredients need to be reconstituted in water for a half hour before use. Use the liquid in a cooked dish.

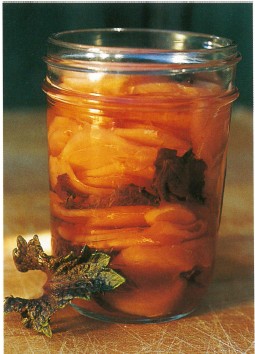

Pickled Foods

Pickled foods are highly appreciated in all of Asia. In Japan, in particular, some meals are simply not complete without the accompaniment of a specific kind of pickle. You can make many of these traditional pickles from your garden produce; see the recipes on pages 63-65.

Sauces and Condiments

For many Asian dishes, characteristic flavor lies in certain sauces. Key ingredients are oyster and hoisin sauces for Chinese food; Thai and Vietnamese fish sauces; and rice vinegar, sake, miso, and dashi for Japanese cooking. In The Modern Art of Chinese Cooking, Barbara Tropp gives detailed information on how to select and use the best of many kinds of Asian seasonings. She recommends both specific brands of these products and local sources all over the country.

Soy Sauce

Soy sauce is a pungent, salty brown liquid made from fermented soybeans, wheat, yeast, and salt. As a rule, Chinese cooks use the dark types for color and the lighter ones for salting dishes. Japanese cooks—who will alternately refer to this sauce as tamari or shoyu—generally use light to medium strengths of soy sauce. A good brand, available in most areas of this country, is the familiar Kikkoman, a medium-strength soy sauce.

Tofu

Tofu, also called bean curd, is a neutral-tasting, custardlike substance made from the curds of soybean milk. The greatest virtues of tofu are its nutritional richness and its ability to absorb flavors. Tofu comes in a range of textures, from silken to extra-firm. Silken tofu is wonderful whipped into desserts such as puddings and pies. The medium firmness, or what I call “regular” is available in most American grocery stores.

Regular tofu, which is ready to use as is or cooked, keeps for four to five days in the refrigerator if rinsed in fresh water daily. Some recipes call for frozen tofu—which is chewier and more porous than fresh—because it soaks up flavor and marinades and gives a meatier texture in the final dish. Standard procedure for fresh tofu is to drain it, sliced, in a colander or on paper towels for half an hour prior to cooking. Simply cut the drained tofu into bite-size pieces or strips and toss it into a soup, stir-fry, or egg dish.

Condiments

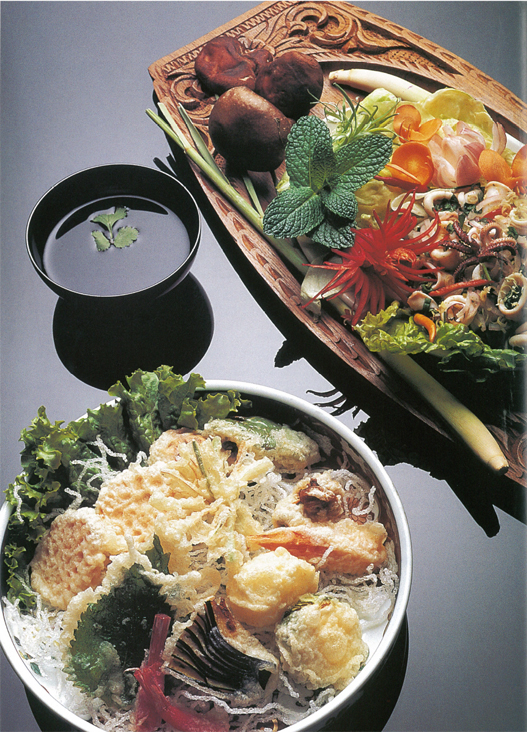

Pickled Daikon and Carrots

Both Helen Chang and Mai Truong have helped me make these pickles. Pickling daikon in this manner is traditional in many parts of Asia. In China, these pickles might be part of a farmer’s lunch, served with rice and a vegetable stir-fry. In Vietnam, showing the influence of the French, the slices might be used in a sandwich with liver-wurst, head cheese, and herbs, or served with noodles and fragrant herbs. In Japan, they would be part of a selection of pickles offered as condiments at a meal.

If you prefer a crisp pickle, parboil the daikon and carrots in a quart of boiling water into which ½ teaspoon of alum has been added. See the recipe for pickled mustard on page 65 for more information on alum.

1 pound white daikon radish, (12 to 16 inches long, 2 inches in diameter)

1 medium carrot

2 teaspoons salt

½-inch slice fresh ginger root

½ cup rice wine vinegar

½ cup sugar

Peel the daikon and carrots and cut them into ¼” X 3” julienne strips. Put the vegetables in a medium bowl and sprinkle the salt over them. Crush the ginger slice with the back of a cleaver and add it to the vegetables. Stir the daikon and carrots with your hands to disperse the salt evenly. Set the bowl aside and let it sit at room temperature for one hour.

Drain the vegetables and then, using your hands, gently squeeze them to remove more of the liquid. Add the vinegar and sugar to the vegetables and stir until thoroughly mixed. Set aside to marinate at room temperature for 2 hours. Drain the mixture and remove the ginger and discard it. Put the pickled vegetables in a tight-sealing container and refrigerate until use. These pickles keep refrigerated for up to 2 weeks.

Makes about 2 cups.

Daikon Spicy Relish

This Japanese relish is a great accompaniment to grilled fish or marinated firm tofu. A little goes a long way, as it is spicy. Because you’ll be stuffing the daikon, straight (rather than curved) chile peppers are easiest to use.

5 thin, dried red chile peppers

1 piece white daikon radish, about 5 inches long

Clockwise from top left: pickled daikon and carrots; daikon spicy relish; picked mustard, before and after; and slices of fresh Red Meat daikon with sugar.

Remove the stems and tops from the peppers. Remove the seeds by rolling each pepper between your fingers to loosen the seeds, then remove them. Peel the daikon and with a sharp chop-stick or an ice pick puncture the sliced end of the daikon about 2 inches deep in 5 places. Force a pepper into each hole. (If the peppers are hard to get in, slice them in half and use the chop stick to work a half in each hole.)

Let the stuffed daikon rest for 5 minutes to soften the chiles. Grate 2 inches of the stuffed daikon over a bamboo rolling mat or cheesecloth. (You need the daikon to be at least 5 inches long to protect your knuckles from the grater.) The remaining 3 inches of daikon can be sliced and added to a soup. Get rid of some of the moisture in the grated daikon by rolling the bamboo mat over and squeezing or by wringing the cheesecloth. Serve the relish at once in an individual serving dish so each diner can season his or her own meal.

Makes ½ cup, serves 4 to 6.

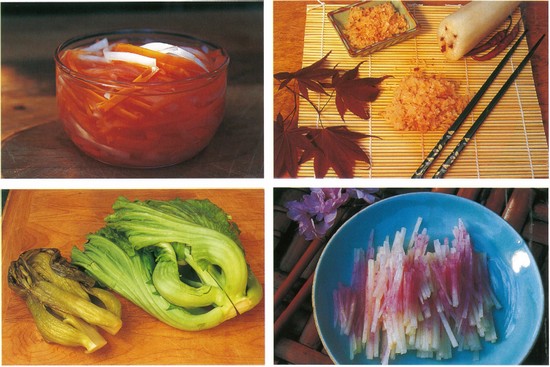

Pickled Ginger (Gari)

Pickled ginger is most popular in Japan invariably accompanying sushi and sashimi. The commercially prepared pickles often have added red food coloring but traditionally it is colored with red shiso leaves (perilla) as it is here.

¼ pound young ginger root

¼ cup rice vinegar

2 tablespoons mirin

2 tablespoons sake

2 tablespoons sugar

6 red shiso leaves

In a small saucepan, bring the rice vinegar, mirin, sake, and sugar to a gentle boil. Stir until the sugar dissolves. Cool the liquid.

Bring a small pot of water to a boil. Brush the ginger under running water, slice thinly, and then blanch slices for one minute. Drain the ginger and then transfer it into a sterilized half-pint canning jar, layering it evenly with the whole shiso leaves. Pour the cooled liquid over the ginger. Cover and let marry for 3 days in the refrigerator before serving. The ginger will keep in the refrigerator for up to 1 month.

Makes ½ pint.

Pickled Mustard

Pickled mustard is a staple in much of Asia. Mai Truong helped me make it the way her Vietnamese mother taught her. Small amounts of the mustard are used to add flavor to stir-fries. It can be eaten over rice for a simple meal, or enjoyed as a condiment. Alum is used to make the pickle crunchier and to retain some of the green color but it is not a critical ingredient. You can get alum at pharmacies and Asian grocery stores. If you can’t make your own, you can buy pickled mustard in the refrigerated section of most Asian markets.

3 quarts water

½ cup kosher salt

4 cups sugar

2 large Chinese mustards (look for solid-hearted varieties such as Amsoi)

1 teaspoon solid alum (or ½ teaspoon powdered alum)

Bring the water to a boil; add the salt and sugar. Stir until the salt and sugar have dissolved. Cool the liquid to room temperature.

Wash the mustard and cut a slit a few inches deep in the large base so the pickling liquid can penetrate the flesh. In a large pot, bring about 4 quarts of water to a rolling boil. Add the alum. Blanch the mustard for about 30 seconds. Drain and cool the mustard to room temperature.

Put the mustard into a large plastic container that can be sealed. Pour the pickling liquid over the mustard; make sure the entire surface is submerged. (If you don’t have enough, make up more pickling liquid and add it.) Put the mustard in a cool, dark place to pickle for a week. The pickled mustard keeps in the refrigerator for a few weeks.

Makes 6 cups or about 1½ pounds.

Tea

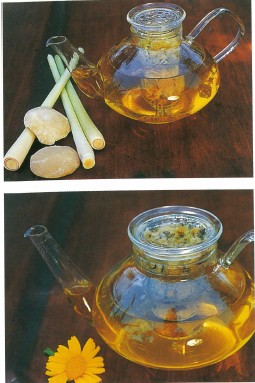

Lemon Grass Tea

Lemon grass makes a sprightly herb tea. Here, it is made with palm sugar (available from Asian grocery stores), but it is also pleasant with standard white sugar. For a variation try adding a little chopped ginger root.

½ cup thinly sliced fresh lemon grass

2 to 3 tablespoons palm sugar (or white sugar)

1 quart cold water

Place the lemon grass and the palm sugar in the bottom of a teapot. Bring the water to a boil and pour it into the teapot over the lemon grass. Let the tea steep for at least 10 minutes. Pour the tea through a strainer and into teacups.

Serves 4.

Chrysanthemum Tea

This tea is famous in China and often served with dim sum.

4 tablespoon dried chrysanthemum flowers

1 quart cold water

Place the dried chrysanthemum flowers (shungiku) in the bottom of a teapot. Bring the water to a boil and pour it over the chrysanthemum flowers. Let the tea steep for at least 10 minutes. Pour the tea through a strainer and into tea cups.

Serves 4.

Steamed Rice

Steamed white rice is basic to all of Asia. In China and Japan they use short-grain rice. In India, however, they commonly use a long-grain, or fragrant basmati rice. The following recipe is the most basic and applicable to most white rice varieties. If you use a rice cooker, follow the proportions and directions that come with it. An interesting variation, and one packed with nutrition, is to make the rice with fresh green soybeans. The beans will cook in the same amount of time as the nee.

1½ cups white rice

2 cups water

Optional: 1 cup shelled green soybeans

Rinse the rice under running water, then drain and place in a pot with a tight-fitting lid. (If using, add the optional green soybeans to the rice at this point.) Cover and bring to a boil. Reduce the heat to low and simmer for 15 minutes. Turn off the heat (don’t lift the lid!) and let it sit covered for another 15 minutes. Fluff lightly and then serve.

Serves 4.

Shanghai Pac Choi Stir-fry

This recipe is a variation on one given to me by my wonderful neighbor, Helen Chang. Tatsoi, or the large types of pac choi, can be substituted for the Shanghai variety.

1 ½ tablespoons vegetable oil

3 slices of fresh ginger root (⅛-inch thick), peeled and finely diced

1 pound Shanghai pac choi, cut diagonally into 1-inch pieces, white stems separated from the greens

1½ to 2 tablespoons oyster sauce

Pour the oil into a wok. Heat over high heat until very hot. Add the ginger and stir-fry quickly until lightly brown. Add the white stems from the pac choi and stir-fry for 2 minutes. Add the greens and continue to stir-fry for 2 or 3 minutes more until the pac choi is tender but still slightly crunchy. Add the oyster sauce and stir to combine and bring the mixture to serving temperature.

Serves 3 to 4 as a side dish.

Carrot and Garlic Stir-fry

This popular vegetable stir-fry contrasts sweet and hot. Its richness combines well with other dishes containing the cool flavors of pac choi, cabbage, or spinach.

1½ tablespoons vegetable oil

1 pound carrots, peeled and cut into coins (about 3 cups)

2 large garlic cloves, peeled and minced

2 green onions, sliced thinly

¼ teaspoon hot red pepper flakes

¼ teaspoon salt

1 to 2 tablespoons chopped fresh coriander leaves

Garnish: coriander leaves

Pour the oil into a wok. Heat over high heat until very hot. Add the carrots and stir-fry for 3 or 4 minutes, add the garlic and green onions and stir to mix. Continue to stir-fry until the carrots are tender but still slightly crunchy. Add the red pepper, salt, coriander and mix. Taste and adjust the seasonings if necessary. To serve, pour contents of wok onto a small platter and garnish with cilantro leaves. Serve at once.

Serves 3 to 4 as a side dish.

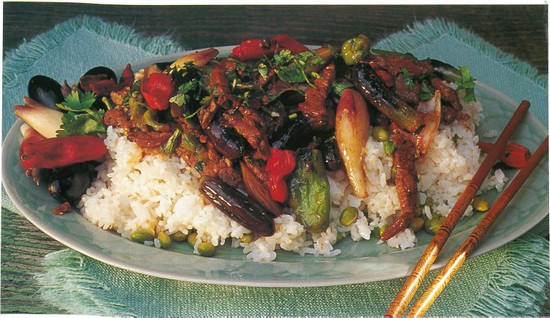

Shishito Pepper and Eggplant Stir-fry with Beef

I learned about cooking baby Japanese eggplants and using mioga ginger blossoms from a woman selling both at the local farmer’s market. Serve this dish with a vegetable stir-fry and rice cooked with soybeans (see the recipe on page 66) for a complete meal.

For the marinade:

1 tablespoon dry sherry

2 tablespoons soy sauce

1 tablespoon cornstarch

½ teaspoon sugar

½ pound beef filet strips

For the stir-fry:

2 tablespoons peanut oil

8 to 10 ounces Japanese baby eggplants, or larger eggplants cut into small strips

1 medium onion, chopped

16 green Shishito peppers or 1 sweet green Italian frying pepper cut into small strips

16 red Shishito peppers or 1 sweet red Italian frying pepper cut into small strips

6 mioga ginger blossoms, quartered (optional)

2 garlic cloves, minced

2 tablespoons fresh coriander leaves, chopped

2 teaspoons grated fresh ginger root

2 tablespoons oyster sauce

½ to ¾ cups chicken broth

½ teaspoon hot red pepper flakes

To make the marinade:

In a small bowl, combine the sherry, soy sauce, cornstarch, and the sugar. Stir until the cornstarch is completely dissolved. Add the beef strips, toss, and set aside.

To make the stir-fry:

Over high heat in a nonstick wok, heat the peanut oil until it is very hot. Add the eggplants and stir-fry over high heat for 3 minutes. Add the onion, green and red peppers, and ginger blossoms; stir-fry 2 more minutes. Toss in the minced garlic, coriander, and grated ginger; cook for a couple of seconds. Put on a plate and set aside.

Heat the wok again, adding a little more peanut oil if necessary, and stir-fry the marinated beef for 1 minute or until medium rare. Return the vegetables to the wok, and then stir in the oyster sauce, the chicken broth, and the red pepper flakes. Heat together for another minute, and then serve the stir-fry at once over rice.

Serves 4.

Pickled Mustard Stir-fry with Pork

Mai Truong, who grew up in Vietnam, shared with me her favorite dish using pickled mustard—in this case with pork. I’ve also enjoyed adding shredded bamboo shoots, pea pods, and carrots to this recipe. Serve this dish with rice and soy sauce. For a complete meal accompany it with another stir-fry and a light soup. If you can’t make your own, pickled mustard is available in the refrigerated section of most Asian markets.

½ pound lean pork, cut in thin strips across the grain

⅛ teaspoon salt

6 garlic cloves, minced, divided

1 pound pickled mustard (see recipe on page 65)

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

Fresh coriander leaves, chopped

Fresh green onions, chopped

Sprinkle the pork strips with the salt and half the minced garlic. Marinate the mixture for about 1 hour. Drain the pickled mustard and chop it into 1-inch pieces. In a hot wok heat the oil. Sauté the remaining garlic until it is starting to turn golden. Add the pork strips and stir-fry until the meat turns gray. Add the pickled mustard and ½ cup of water. Cook for 3 more minutes, transfer to a warm platter and garnish the dish with coriander and green onions.

Serves 4.

Bitter Melon with Beef Stir-fry

Bitter flavors are an acquired taste, but if you enjoy bitter beer and radicchio you’ll probably delight in this rich and complex dish. Serve it with steamed rice.

1 tablespoon dry sherry

1 tablespoon soy sauce

1 tablespoon cornstarch

½ pound beef tenderloin, cut in thin strips across the grain

1 pound bitter melon

½ teaspoon salt

1 red bell pepper

2 tablespoons peanut oil, divided

2 garlic cloves, minced

1 tablespoon grated fresh ginger root

2 tablespoons black bean sauce

2 teaspoons sugar

Garnish: 2 tablespoons of chopped fresh coriander leaves

Combine sherry, soy sauce, and cornstarch in a small bowl. Add the beef strips, coat thoroughly and set aside. Cut the bitter melon lengthwise; remove inside pulp and seeds. Slice thinly. Put into a bowl and sprinkle with salt. Let the melon sit for 20 minutes to remove some of the bitterness. After 20 minutes, squeeze out the water. Cut the red pepper in thin slices.

In a hot wok, heat one tablespoon of the oil. Add the bitter melon, garlic, and ginger and stir-fry for about 3 minutes. Remove the vegetables and put them on a warm serving plate. Add the remaining tablespoon of oil to the wok, heat and then add the beef strips. Stir over high heat until meat starts to brown but is still pink inside. Add the marinating juices, bean sauce, 1 cup water, and the sugar. Cook for one more minute, but do not overcook. Arrange the beef strips over the vegetables on the platter. Garnish with chopped coriander.

Serves 4.

Pea Shoots with Crab Sauce

Pea shoots are a special vegetable and greatly enjoyed in China. Here is an elegant pairing with crab.

For the sauce:

2 garlic cloves, minced

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

1 tablespoon cornstarch

1 cup chicken stock

2 tablespoons sherry

½ pound cooked crabmeat (about 1 cup)

¼ cup chopped, blanched Chinese leek leaves or 1 tablespoon chopped fresh Oriental chive leaves

Salt

For the pea shoots:

1 tablespoon sesame oil

1 quart coarsely chopped fresh pea shoots

To make the sauce: In a saucepan over low heat, Sauté the garlic in the vegetable oil until tender, about 1 minute. In a small bowl, blend the cornstarch with the chicken stock and sherry. Add the mixture to the pan and heat, stirring constantly until the sauce is thickened. Add the crabmeat and the Chinese leeks and simmer for another minute. Remove from the heat, and add salt to taste.

To make the pea shoots: In a wok or large pan, heat the sesame oil and stir-fry the pea shoots for about 3 minutes or until just tender. Lightly toss them with the sauce and serve them over steamed rice.

Serves 4.

Stir-fried Shrimp and Greens

David Cunningham, one time staff horticulturist at the Vermont Bean Seed Company, created this recipe to take advantage of his many Asian greens. Serve this stir-fry with steamed nee.

For the shrimp marinade:

1 tablespoon tomato paste

1 tablespoon cornstarch

1 tablespoon soy sauce

2 tablespoons vinegar

2 tablespoons water

½ teaspoon Chinese mustard

1½ pounds raw shrimp, shelled, cleaned, and deveined

For the sauce:

½ cup chicken stock

1 tablespoon cornstarch

1 tablespoon soy sauce

2 teaspoons honey

4 large garlic cloves, minced

For the stir-fry

¼ cup peanut oil, divided

2 large heads pac choi, stems sliced diagonally in 2-inch pieces

4 green onions, sliced diagonally

1 quart tatsoi leaves

To make the marinade: Mix the marinade ingredients together, add the shrimp, and refrigerate for 3 hours. Drain and reserve both the liquid and the shrimp.

To make the sauce: Mix the sauce ingredients together, add the drained marinade liquid and set aside.

To make the stir-fry: Heat the wok over high heat and add about half the oil. Stir-fry the shrimp quickly in small batches. As they are cooked, put the shrimp and any juices into a bowl and reserve.

Add the remaining oil and stir-fry the pac choi stems and green onions for about one minute. Add the tat soi leaves and stir until they are wilted. Add the sauce, lower the heat, and stir until thickened. Add the cooked shrimp together with their liquid. Heat all together while stirring, for another minute.

Serves 6 to 8.

Gai Lon with Bamboo Shoots and Barbecued Pork

Helen Chang helped me develop this recipe. She showed me how to prepare the gai lon by leaving only the rich tasting stalks and young buds. Purchase barbecued pork at gourmet and Asian markets. Accompany the stir-fry with rice, a light soup such as chive dumpling soup (see recipe on page 76), or other stir-fried dishes.

1 pound of gai lon (about 5 cups trimmed)

½ teaspoon salt

2½ tablespoons peanut oil, divided

¼ pound Chinese barbecued pork at room temperature, sliced thinly

3 slices fresh young ginger, or

2 slices mature ginger, 2 inches long, crushed slightly

2 green onions, white part only, chopped finely

½ cup fresh or frozen bamboo shoots, sliced thinly

2 tablespoons oyster sauce

Wash the gai lon well to remove any grit. Peel the skin of the largest stems and remove any large tough leaves. Cut the stalks into 3- or 4-inch lengths. Cut the widest stems lengthwise, so they cook in the same amount of time as the smaller pieces.

Bring a large pot of water to a boil; add ½ teaspoon of salt and then the gai lon and parboil for 1½ minutes. Pour the gai lon into a colander and set aside to drain.

Heat the wok over high heat and when very hot add ½ tablespoon of oil and then add the pork and stir-fry for 30 seconds. Remove the pork to a plate. Add the remaining 2 tablespoons of oil, the ginger, and green onions and stir-fry for 30 seconds. Add the drained gai lon and the bamboo shoots and stir. Then, add the barbecued pork and the oyster sauce. Stir and cook until the gai lon is tender, about 2 more minutes. Transfer the mixture to a warm plate and serve with rice.

Serves 2 as a single entree with a soup. Serves 4 as part of a traditional Chinese meal combined with other stir-fry dishes.

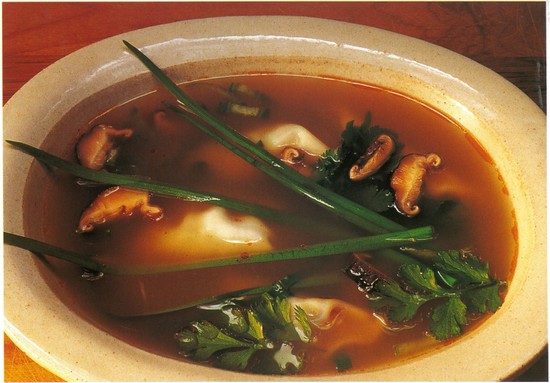

Miso Soup

Miso soup is a traditional Japanese soup, eaten most often at breakfast. Miso paste is made from fermented soybeans and can be found in Asian and natural-food stores in plastic tubs. There are all different kinds of miso—ranging in color from blonde to rich reddish-brown—depending on the ingredients from which it is made, the length of the fermentation process, and season. Miso contains acidophilus—the “helpful” bacteria found in yogurt—which will perish if miso is boiled.

Some versions of this soup are made with dashi (bonito flake stock) and kombu (seaweed). The version that appears here is suited more to Western tastes and is a great way to get acquainted with this lovely soup. After you have made it a few times try adding some kombu and/or dashi to the simmering water—but be careful, as the flavor from these ingredients can overpower your soup. Put the dashi in cheesecloth and use it as a “teabag” to flavor your miso gently. Kombu contains agents that accelerate the softening of the soup’s vegetables while they cook. If used, both the dashi and the kombu should be removed from the soup just before the water begins to boil.

1-inch piece of fresh ginger root, sliced

1 medium carrot, minced

4 ounces firm tofu, in ½-inch cubes

¼ cup miso paste (more or less to taste)

2 scallions, minced

Bring one quart of water and the ginger slices to a boil. Simmer for 5 minutes, then remove the ginger. Add the minced carrot and tofu, and simmer for another 2 minutes. Take the soup off the stove and allow to cool for 1 to 2 minutes. Add the miso and stir gently until it dissolves. Scatter the minced scallion on top and serve immediately.

Serves 4.

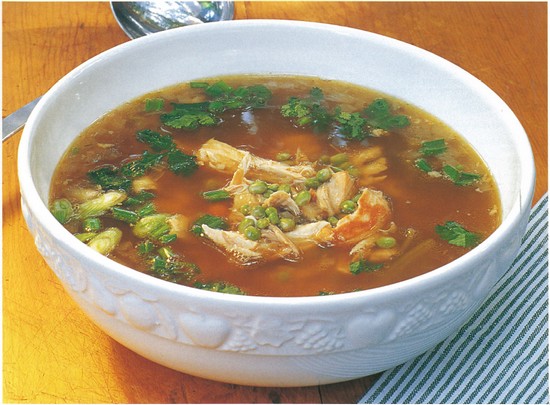

Thai Chicken Soup with Pigeon Peas

This lovely light soup is a great beginning to a Thai meal or Chinese stir-fry. Some folks enjoy the fish sauce that gives an authentic Thai taste; others prefer to leave it out.

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

1 frying chicken (3 to 3½ pounds), cut in 6 or 7 pieces

1 large onion, chopped

3 ribs celery, chopped

2 medium carrots, chopped

3 stalks lemon grass, chopped in 2-inch pieces and slightly crushed to release flavors

1½ tablespoons grated fresh ginger root

4 garlic cloves, minced

4 leaves Kaffir lime leaf

3 whole dried chiles

½ teaspoon ground coriander seeds

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

2 cups shelled fresh pigeon peas or green peas (preferably fresh)

2 small green onions sliced thinly, including 1-inch of the greens

1/3 cup chopped fresh coriander leaves

1 tablespoon lime juice

Optional: 1 tablespoon Thai fish sauce

In a very large sauté pan, heat the oil on medium. Add a few chicken pieces and brown on all sides. Repeat the process with the remaining chicken. Transfer the browned chicken to a large soup pot. Pour off the excess fat from the pan and add the onions. Sauté until translucent, about 7 minutes. Add the onions to the chicken along with 2 quarts of water. Add the celery, carrots, lemon grass, ginger, garlic, lime leaf, chiles, and ground coriander and bring to the boil. Skim off and discard any foam, reduce the heat, then simmer for 45 minutes.

Pour the chicken and liquid through a colander. Pour the stock back into the soup pan and let the fat rise to the top. Skim off and discard most of the fat on the surface. Meanwhile, cool and separate the chicken meat from the bones and skin, and add the meat back to the stock. You should have about 3 cups of chicken meat.

Bring the soup back to a boil and add the pigeon peas and green onions and cook for about 5 minutes, just until the peas are tender. Add the coriander leaves, the lime juice, and the (optional) fish sauce to taste.

Daikon and Spare rib Soup

This recipe was given to me by Helen Chang. Growing up in Taiwan she remembers her mother making this soup often. Traditionally it is served along with the meal. When we first made it together I was surprised at how easy it was and how flavorful and mild the daikon became. When you buy the spareribs have the butcher cut them across the bones so they are in strips 1½ inches wide.

¾ pound pork spareribs, cut crosswise

1½-inch piece fresh ginger root, divided

¾ teaspoon salt, divided

1 medium white daikon radish (about 16 inches long

1 large carrot

⅛ cup dried scallops, in ½-inch cubes

¼ cup Virginia ham, in ¼-inch cubes

Pinch of white pepper

To prepare the pork, remove the membrane and extraneous fat from the back of the ribs. Cut the ribs apart between each rib to create pork rib sections about 1½ inches in diameter.

Fill a medium saucepan with about 2 inches of water and bring it to a boil. Add a 1-inch piece of the ginger and ½ teaspoon of salt to the water and bring it back to the boil. Add the ribs and bring the water to boil once again. Simmer the ribs for three minutes and then drain and rinse in cold water to remove any scum. Discard the ginger and set the pork aside.

Bring 6 cups of water to a boil in the soup pot and add two ¼-inch thick slices of ginger, the pork ribs, and the remaining ¼ teaspoon of salt. Bring the mixture to a simmer and cook for 45 minutes.

In the meantime, prepare the vegetables. Peel the daikon and cut them into 1½-inch oblique chunks. (You should have 2½ to 2¾ cups of daikon.) Peel and cut the carrot into chunks. (You should have about 1 cup of cut carrot chunks.) Once the pork has simmered for 45 minutes add the daikon and carrots and simmer for 35 to 45 minutes longer, or until the carrots are tender and the daikon has turned translucent.

Once the vegetables are done, remove the pan from the heat and add the pepper and adjust the seasonings. Skim any excess fat from the surface and either serve immediately or refrigerate and reheat before serving.

Serves 4 to 6.

Dumpling Soup with Oriental Chives

This recipe was created by Helen Chang of Los Altos, California. A native of Taiwan, her version of this classic soup is light and savory and a marvelous way to use your harvest of Oriental chives. The dough for the dumplings can be purchased already prepared, in the produce or frozen food section of your supermarket, or in Asian markets. Sometimes they are called wonton skins, other times pasta wraps. You can easily substitute 1 large bunch of spinach for the pac choi greens.

For the dumplings:

⅓ pound ground pork

¾ cup finely chopped green cabbage

1/3 cup finely grated carrots

½ cup finely chopped fresh Oriental chive leaves

4 tablespoons finely grated peeled fresh ginger root, divided

2 tablespoons chopped coriander leaves

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon sugar

3 teaspoons cornstarch

1 egg, lightly beaten

1 (12-ounce) package of small square wonton skins, thawed if frozen

For the soup:

2 quarts chicken broth

10 to 12 mushrooms, thinly sliced

1 large head of pac choi, green leafy sections cut in narrow strips; large white stems reserved for another use

Hot pepper sauce (optional)

Garnish: 3 teaspoons chopped coriander leaves

To make the dumplings: In a medium bowl, place the pork, cabbage, carrots, chives, 2 tablespoons grated ginger, coriander leaves, pepper, salt, sugar, and cornstarch. Add the egg and stir to combine the ingredients.

Place the wonton skins, a few at a time, on a clean work surface. (Meanwhile, keep the rest of the wontons in the package, or place a slightly damp towel over them to prevent them from drying out.) Mound a teaspoon of filling in the middle of each wonton square and then fold to form a triangle or semicircle. Press the edges together to seal, then bend corners toward each other as you would for wontons. (Refer to the wonton package for folding directions.) Place the folded dumplings on a cookie sheet, leaving space between each one. Cover and refrigerate dumplings when filled, if not using immediately.

When ready to serve, bring a large pot of water to boil and add the dumplings and simmer for 5 to 6 minutes, or until they become translucent. Remove them from the water with a slotted spoon and divide them among 6 bowls.

To make the soup: In the meantime, pour the chicken broth into a large soup pot. Add the remaining 2 tablespoons of ginger. Bring to a simmer and add the mushrooms. Simmer over low to medium heat for one minute. Add the pac choi leaves and chives to the simmering broth. Add hot sauce to taste, if using.

To serve: Fill the bowls with broth and pac choi. Garnish each bowl of dumplings with chopped coriander.

Serves 6.

Henry’s Salad with Vietnamese Coriander

Henry Tran is both a friend and landscaping contractor with whom I work. He has helped me identify a number of Vietnamese greens and herbs over the years and generously shared the traditional ways they are used in Vietnam. The following is one of his salad suggestions.

2 teaspoons sugar

1 small Vidalia, Maui, or other sweet white onion, sliced paper thin

2 tablespoons rice vinegar

2 teaspoons low-sodium soy sauce

1 teaspoon finely chopped fresh Vietnamese coriander

½ teaspoon finely chopped mint or spearmint

⅛ teaspoon hot red pepper flakes

Pinch of salt

⅛ teaspoon finely chopped fresh ginger root (optional)

6 cups butter lettuce, washed and dried

Garnish: 4 sprigs fresh Vietnamese coriander

Pour 1½ cups of water into a medium bowl. Add the sugar and stir until it has dissolved. Separate the onions into rings and add them to the bowl. Allow the mixture to sit for 30 minutes.

In a small mixing bowl, combine the rice vinegar, soy sauce, Vietnamese coriander, mint, chile flakes, salt, and the ginger, if being used, to make the dressing.

In a large bowl, toss the lettuce with the dressing, coating the leaves well. Divide the lettuce among four plates. Drain the onions. Divide and place them atop each serving. Garnish each salad with a sprig of Vietnamese coriander.

Serves 4.

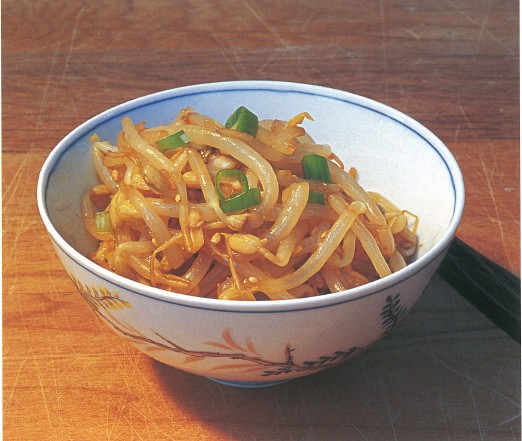

Spicy Bean Sprouts

Many Asian cultures enjoy bean sprout salads. This is a spicy Korean version.

For the dressing:

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

2 teaspoons hot sesame oil

1 tablespoon toasted sesame seeds, ground

2 garlic cloves, minced

2 green onions, finely chopped

¼ cup soy sauce

1 teaspoon sugar

½ teaspoon cayenne pepper

Garnish: 1 teaspoon whole toasted sesame seeds

For the salad:

1 pound fresh mung bean sprouts

To make the dressing: Combine all the ingredients in a small jar, cover and shake vigorously.

To make the salad: Carefully wash the bean sprouts. Bring 2 quarts of salted water to a rolling boil. Add the sprouts and cook them for 1 minute. Do not overcook, as the sprouts should remain crunchy. Drain and rinse with cold water. In a bowl, toss the sprouts with the dressing and chill for about 1 hour. Sprinkle with whole sesame seeds before serving.

Serves 4.

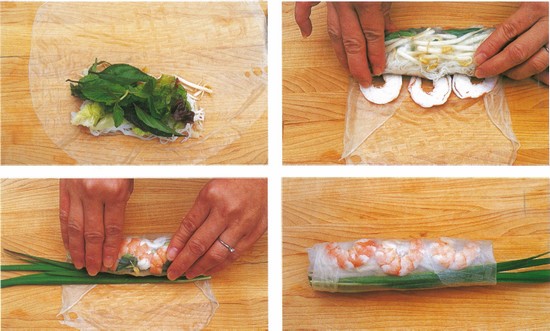

Vietnamese Salad Rolls (Goi Cuon)

This elegant recipe is a fabulous way to feature all your Southeast Asian herbs. It is a traditional dish and was given to me by Mai Truong, who grew up in Vietnam. It makes a great light first course or a special luncheon dish. Use leftover fish dipping sauce for a light salad dressing.

1 pound pork loin (or use leftover roasted or grilled pork loin)

16 to 20 medium raw shrimp

6 ounces fine rice vermicelli

1 large head leaf or butter lettuce

5 to 6 cups loosely packed fresh herb leaves including: mint, Thai basil, perilla leaves, rau ram, and cilantro

2 cups mung bean sprouts

1 12-ounce package of 11-inch egg roll wrappers (made with wheat flour, tapioca, and water)

1 large bunch garlic chive leaves

1 tablespoon hot chile paste

In a saucepan, bring a quart of water to a boil. Add the pork loin; cover and simmer on low heat for about 20 to 30 minutes or until tender. Drain and cool the pork. In another saucepan, bring 2 cups of water to a boil, add the shrimp and simmer on low for about 3 minutes. Drain and set them aside. In a third pot, bring a quart of water to a boil, add the vermicelli and cook for 3 minutes. Drain, rinse in cold water, and set aside.

Before assembling the rolls, cut the pork into thin slices. Peel and devein the shrimp and slice each in half lengthwise. Wash and drain the lettuce and herbs. Place the pork, shrimp, vermicelli, lettuce leaves, herb leaves, and bean sprouts in bowls near a clean work surface.

Fill a large bowl with warm water and keep it at your work table. Dampen one egg roll wrapper at a time by dipping the edges into the warm water; place it on your work surface and dampen the middle by sprinkling it with water. Spread the moisture around with your fingers so the wrapper becomes evenly moist, but not wet. Let the wrapper soften a few seconds. (The thickness of the salad rolls can vary—it depends on how much filling you put in. After you fill and roll a few you will determine the final size you prefer.)

To fill the first wrapper, spread several strands of noodles on it, 2 inches from the bottom. Cover with part of a lettuce leaf, a selection of 3 or 4 different herb leaves, a small amount of bean sprouts, and three slices of the pork on top of each other. Fold the bottom part of the wrapper over the ingredients and fold in both sides of the wrapper, as you would to make a burrito. Place 3 shrimp halves and 3 whole garlic chive leaves on the top of the first roll of the wrapper, letting the chives stick out on one side. Finish rolling the wrapper up until it forms a cylinder. The shrimp will be visible from the outside through the wrapper. Repeat assembly for each roll.

Place the finished rolls on a serving platter and garnish, or make up individual plates of 2 or 3 rolls each. Accompany the rolls with a small bowl of hoisin dipping sauce, another small bowl of fish dipping sauce, and a bowl of the hot chile paste.

Makes 10 to 12 rolls, serves 4 to 6.

(Above, left) To roll the salad rolls, first place the ingredients on the damp wrapper a few inches from the bottom. (Above, right) Fold the bottom part of the wrapper over the ingredients, then bring over the sides. Place 3 shrimp in front of the rolled part and roll a half turn. (Below, left) Place a few chive leaves on the wrapper then roll another turn until the roll is finished (below, right).

For the hoisin dipping sauce:

½ cup hoisin sauce

2 tablespoons water

1 tablespoon unsalted, dry-roasted peanuts, finely chopped

Blend the hoisin sauce with the water. Put it in a small serving bowl and sprinkle with the chopped peanuts.

For the fish dipping sauce:

3 to 6 garlic cloves, minced

3 fresh serrano peppers, seeded and minced

¼ cup fresh lemon juice

⅓ cup Vietnamese fish sauce (nuoc nam)

¼ cup sugar

With a mortar and pestle, crush the garlic and peppers into a smooth paste. Put the lemon juice into a glass bowl, add the garlic-pepper paste, fish sauce, sugar, and ¾ cup warm water. Stir to combine. This dipping sauce can be kept in a jar in the refrigerator for several weeks.

Makes 1½ cups.

Beef and Pork Japanese Vegetable Rolls

The Japanese have many elegant meat and vegetable combination appetizers and this is one.

For the sauce:

¼ cup water

1 tablespoon sugar

1 tablespoon mirin

3 tablespoons soy sauce

For the rolls:

2 medium carrots (about 4 ounces)

1 burdock root (about 4 ounces)

1 tablespoon white vinegar

6 green onions

4 ounces yard-long beans

1 teaspoon soy sauce

10 ounces lean beef or pork, teriyaki style, and thinly sliced

2 tablespoons cornstarch

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

To make the sauce: Combine the water with the sugar, mirin, and soy sauce and set aside.

To make the rolls: Cut the carrots lengthwise into strips about 5 inches long and ¼ inch square. Peel the skin off the burdock root and cut it into the same size strips as the carrots. To prevent discoloration, soak the burdock in water with the vinegar for 5 minutes. Cut the green onions and set them aside. Cut the yard-long beans into 5-inch lengths.

In a small saucepan, bring ¼ cup water to a boil, add 1 teaspoon soy sauce, the carrots, and the burdock root. Simmer the vegetables for 5 minutes, drain them, and set aside. Parboil the beans in 2 cups of water for 3 minutes, cool them quickly under running cold water, drain them, and set them aside.

Spread the beef or pork slices on a cutting board and sprinkle them lightly with cornstarch.

To assemble: Put 2 pieces of each vegetable and green onions on a piece of meat and roll them up tightly. Secure the rolls with a wooden toothpick. When all the rolls are done, sprinkle them lightly with cornstarch.

To serve: In a nonstick frying pan, heat the vegetable oil and brown the rolls evenly on all sides. You may have to do this in 2 batches. Return all the rolls to the pan and pour the sauce over the rolls and simmer them for another 5 minutes, turning them in the sauce so they are evenly glazed. Serve on individual plates while still warm.

Serves 4.

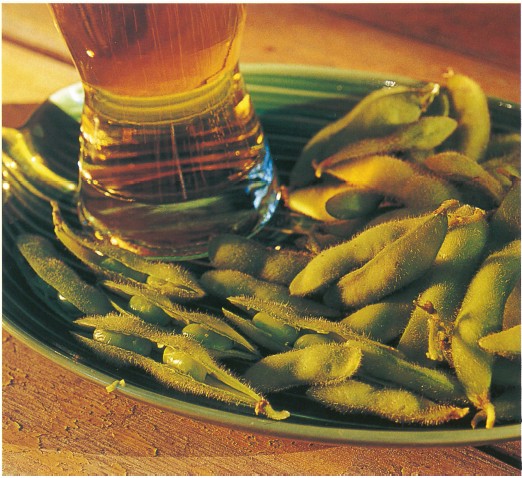

Edamame

This recipe was suggested to me by June Tachibana, who sells fresh soybeans at the Palo Alto farmer’s market. She says this traditional Japanese snack is often enjoyed with beer. Salt helps keep the soybeans bright green.

2 tablespoons salt

½ pound fresh green soybeans, pods on

Pour 2 quarts of water in a large saucepan and bring it to a boil. Add the salt and stir to dissolve. Add the soybeans and boil them for 4 to 6 minutes and until the beans are tender and still firm but not mushy. Drain the beans in a colander. Put the beans in a bowl and serve. Have snackers peel their own beans and provide them with an extra bowl for the empty pods.

Serves 2 as a snack.

Spinach Puree

This spinach recipe is typical of many recipes from India; it contains many complex flavors yet is surprisingly light.

3-inch piece fresh ginger root, divided

3 green chiles, seeded and membranes removed

1 pound fresh spinach, washed and drained

3 tablespoons butter

1 small onion, minced

½ teaspoon salt

Dash of freshly grated nutmeg

Dash of cayenne pepper

Garnish: shredded fresh ginger root

In a large pot, bring 1 cup of water to a boil. Slice off 2 inches of the ginger and add to the water. Shred the remaining ginger for the garnish. Chop the green chiles and add to the pot. Add the fresh spinach and cook for about 3 minutes. Drain the liquid and puree the mixture in a blender, and set aside.

In a pan, melt the butter and sauté the onion until it is soft. Add the pureed spinach to the onion and stir to combine. Season with salt, nutmeg, and cayenne pepper. Serve hot, garnished with shredded ginger.

Serves 4.

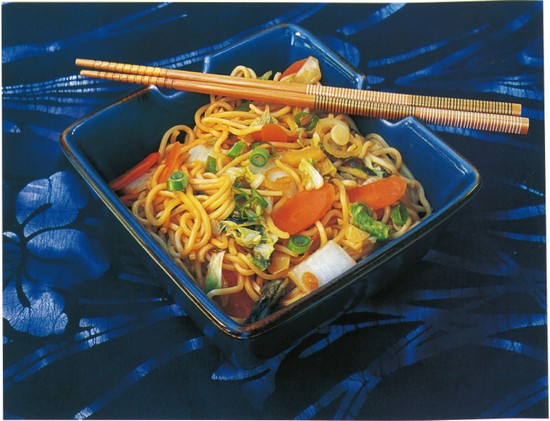

Japanese Noodles

Noodles of many types are popular in Japan. I am most fond of the fresh noodles available in Asian grocery stores and usually keep some on hand. They are found in the refrigerator section and are sealed in plastic; they usually keep for a few months. Americans are most familiar with these ramen noodles in their dried form. The following is a much more satisfying dish than the dried commercial version and contains a lot more nutrition.

2 tablespoons corn oil

1¼ pounds fresh Japanese noodles

½ cup chopped pickled mustard (see the recipe on page 65, or buy it in an Asian market)

1 cup Chinese cabbage ribs, sliced

1 medium carrot, thinly sliced

1 large shallot or small onion, diced

4 cups Chinese cabbage leaves, chopped

½ cup chicken stock

1 tablespoon Worcestershire sauce

½ teaspoon chili powder

½ teaspoon sugar

½ teaspoon salt

Garnish: 1 sliced green onion

In a wok, heat the corn oil over high heat. Add the pickled mustard, ribs of Chinese cabbage, and sliced carrots. Stir-fry for 2 minutes. Add the shallot and the chopped leaves of the Chinese cabbage and stir-fry 1 minute more. Toss in the noodles and cook for 2 more minutes. Add the chicken stock, Worcestershire sauce, chili powder, sugar, and salt. Cook 1 minute more to combine the flavors. Serve in a bowl garnished with sliced green onion.

Serves 2.

Winter Squash, Japanese Style

Braising vegetables with dashi is a favorite Japanese way to cook many vegetables. If you are new to dashi and its taste of the sea, you might want to replace half the dashi with water. Dashi may be purchased in dried form in Asian markets. Note that the soy will darken the squash; if you wish to retain the color, add the soy sauce to the broth in the bottom of the serving bowl instead of during the cooking.

1 pound winter squash, Japanese Kabocha or ‘Red Kuri’

¾ cup reconstituted dashi

2½ tablespoons sugar

1 tablespoon mirin

1 tablespoon soy sauce

Wash the squash and cut it in half to remove the cubes. Cut it into 2-inch squares. Slice off the skin here and there to give the surface a mottled look and to enable the flavor of the broth to penetrate. Put the squash skin-side down in a saucepan, add the dashi, sugar and mirin. Cover and simmer for 7 to 8 minutes over medium heat. After 4 to 5 minutes turn the pieces over gently one by one. Add the soy sauce and continue to simmer 7 to 8 minutes more or until tender, turning the squash over once while simmering. Test for tenderness and remove the squash just as it softens. Serve hot or at room temperature.

Serves 4 as a side dish.

Green Beans with Sesame

This is a lovely side dish to accompany grilled tofu or fish and rice in a Japanese meal. The daikon pickles on page 63 would fill out the meal. Dashi can be purchased in dried form from Asian grocery stores. Nori is the flat, pressed seaweed sheets that are used to make sushi rolls. It can also be purchased at Asian grocery stores.

Optional: 1 sheet of nori seaweed

2 cups yard-long or standard green beans

½ cup sesame paste

½ cup basic dashi (made following the directions on the package)

3 teaspoons light soy sauce

4 teaspoons sugar

If using the nori, lightly toast the sheet in a dry frying pan. Take it out of the pan, cut it into narrow strips, and set it aside.

Boil the beans in slightly salted water until just tender. Drain and cool under cold running water. Cut the beans into 2-inch lengths. Mix the sesame paste, reconstituted dashi, soy sauce, and sugar to make a sesame dressing. Put the beans into 4 serving bowls, top each with a spoonful of the dressing and garnish with the shredded nori.

Serves 4 as a side dish.

Spicy Eggplant

This is a classic Indian treatment of eggplant filled with lots of fragrant spices. Serve with grilled meats, Indian flat bread or pita bread, and Raita.

For the Masala spice mixture:

1½ teaspoons ground coriander

2 teaspoons ground cumin

½ teaspoon ground red pepper

1 bay leaf

⅛ teaspoon cinnamon

⅛ teaspoon freshly ground nutmeg

Dash of ground cloves

Dash of ground cardamom

For the eggplant:

1 pound eggplant (2 medium)

1½ tablespoons vegetable oil

1 tablespoon butter

2 medium onions, finely chopped

Masala spice mixture

3 medium fresh tomatoes, peeled, seeded, and chopped

2 or 3 green chiles, seeded and chopped

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

1 tablespoon fresh chopped coriander

Combine the spices and set aside. Preheat a gas, electric, or charcoal grill. Cut the eggplants in half lengthwise and cut scores into the flesh, without cutting through the skin. Rub the eggplant halves with a little vegetable oil and grill until the skin blackens and the eggplants are soft. Cool, then peel, and chop the flesh coarsely.

In a medium pot, heat the remaining vegetable oil and the butter and Sauté the onions until they are golden. Add the Masala spices and cook together for 1 minute. Add the tomatoes and green chiles and Sauté for 3 more minutes. Remove and discard the bay leaf. Add the chopped eggplant and sauté until the mixture is dry and comes away from the sides of the pan. Add salt and freshly ground pepper to taste and garnish with the coriander leaves. Serve hot or at room temperature.

Serves 4.

Shungiku Greens with Sesame Dressing

Cooked greens with a sesame dressing is a popular vegetable side dish in Japan. Serve the greens with grilled fish, rice, and one or two types of pickles for a typical Japanese meal.

For the dressing:

1 teaspoon toasted sesame seeds, ground

1 teaspoon sugar

2 tablespoons chicken stock

⅓ cup soy sauce

For the salad:

1 pound shungiku greens

Garnish: 1 teaspoon toasted sesame seeds, whole

To make the dressing: Combine all the ingredients in a small jar, cover and shake vigorously.

To make the salad: Wash the shungiku greens and remove any thick stems. Bring 2 quarts of water to a rolling boil. Add the greens and cook for 1 minute. Drain and rinse with cold water. Press the water from the shungiku and put into a bowl. Dress the greens with the sesame dressing and sprinkle with whole, toasted sesame seeds.

Serves 4.

Spicy and Sour Squid Salad

Chef Areeawn Fasudhani, of the Khan Toke Thai House in San Francisco, created this lovely dish. Note that naw pla, listed among the ingredients, is a salty fish sauce commonly used in Thai cooking. It is bottled like soy sauce and is available in Asian markets.

½ pound cleaned and sliced squid (about 1 cup)

1 tablespoon finely chopped lemon grass

2 tablespoons lime juice

1½ tablespoons nam pla (Thai fish sauce)

1 tablespoon sliced shallots

1 teaspoon chili powder, or finely chopped hot peppers to taste

1 teaspoon finely chopped coriander root (if available)

1 teaspoon chopped green onions

1 teaspoon coriander leaves

Lettuce or cabbage leaves

10 mint leaves

Sprigs of fresh coriander

Dip the squid into boiling water for 30 seconds; drain, then put it in a bowl. Season with the lemon grass, lime juice, nam pla, shallots, chili powder, coriander root, green onions, and coriander leaves. Toss lightly. Place mixture on serving plate next to lettuce or cabbage; decorate with the mint and coriander leaves. Serve immediately. Eat by scooping up squid and juices together with the lettuce or cabbage leaves.

Serves 2 as salad or 4 as appetizer.

Gado-Gado

This is a classic Indonesian dish and has many variations. I like this one as it contains so many vegetables. It makes a wonderful vegetarian lunch.

For the sauce:

1 cup chunky peanut butter

3 garlic cloves, minced

3 to 5 chiles, minced

2-inch piece fresh ginger root, grated

⅓ cup soy sauce

1 teaspoon sugar

1 teaspoon salt

2 Kaffir lime leaves (fresh or dried)

¼ cup fresh lime juice

For the vegetables:

3 cups yard-long beans, cut in 2-inch lengths

3 medium carrots, julienned

3 cups fresh spinach, loosely packed

3 cups chopped Chinese cabbage

2 cups fresh bean sprouts

3 tablespoons vegetable oil

5 ounces firm tofu

½ medium onion, thinly sliced

4 hard-boiled eggs

To make the sauce: In a pot, combine the peanut butter, garlic, chiles, ginger, soy sauce, sugar, salt, lime leaves, and 2½ cups water. Bring the mixture to a boil and simmer, stirring often, for 30 minutes. Cool the sauce, stir in the fresh lime juice, and reserve.

To make the vegetables: In a large pot, bring 2 quarts of salted water to a rolling boil. Add the long beans and carrots and cook them for 2 minutes. Remove them from the cooking water with a slotted spoon, rinse with cold water, and set them aside. Bring the water to a boil again and blanch the spinach, Chinese cabbage, and bean sprouts for 30 seconds. Drain and set aside.

To serve: In a frying pan, heat the vegetable oil and fry the tofu on all sides until golden brown. Drain on a paper towel and set aside. Add the sliced onions to the same pan and fry over medium heat until golden. Drain them on a paper towel and reserve. Quarter the hard-boiled eggs. Slice the tofu ¼inch thick. In a serving bowl, toss the vegetables with the peanut sauce. Garnish with the sliced tofu, the quartered eggs and the fried onions.

Serves 4 to 6.

Thai Red Vegetable Curry

Red curry is one of the traditional dishes in Thailand. It is very spicy, and lush with coconut milk. Shrimp paste is available in Asian markets.

For the red curry paste:

5 to 10 dried red chile peppers

1 tablespoon cumin seeds

1 teaspoon caraway seeds

20 whole black peppercorns

1 tablespoon whole coriander seeds

4 Kaffir lime leaves (fresh or dried)

3 shallots, minced

6 garlic cloves, minced

1 2½-inch piece fresh ginger root, grated

2 stalks lemon grass, finely minced (white part only)

¼ cup vegetable oil

1 tablespoon fresh grated lime peel

1 tablespoon shrimp paste

For the vegetable curry:

3 carrots, peeled and thinly sliced

2 cups snow peas, strings and stems removed

1 cup peeled white daikon radish, cut into julienne strips

6 baby turnips

1 cup broccoli, in small florets

2 cups chopped Chinese cabbage

1 cup tatsoi leaves

1 cup chopped pac choi

1 cup chopped mustard greens

¼ cup red curry paste (see above)

1 can (13.5 ounces) unsweetened coconut milk

2 teaspoons salt

1 tablespoon palm sugar or granulated sugar

¼ cup fresh lime juice

To make the red curry paste: Remove the stems and seeds from the chiles. Soak them in hot water for 15 minutes. Set them aside. In a dry cast-iron pan, toast the cumin seeds, caraway seeds, peppercorns, and coriander seeds over low heat until fragrant, about 3 minutes. Cool the spices and then grind together with the Kaffir lime leaves in a spice or coffee grinder until very fine.

Drain and chop the chile peppers. In a pan over low heat, Sauté the chile peppers, shallots, garlic, ginger, and lemon grass in the vegetable oil until tender, about 5 minutes. Put the vegetables, ground spices, lime peel, and shrimp paste into the bowl of a food processor and process until you have a smooth paste, scraping down the sides once or twice. Stored in a sealed jar in the refrigerator, the paste keeps for about 3 weeks.

Yields 1 cup.

To make the vegetable curry: In a large pot, bring 2 quarts of salted water to a rolling boil. Add the carrots, snow peas, daikon, turnips, and broccoli and blanch for 2 minutes. Remove the vegetables with a slotted spoon, rinse them under cold running water to set the color and set them aside. Bring the water to a boil again and blanch the greens briefly. Drain and rinse them with cold water and set them aside with the other vegetables.

In a large pan, over low heat, Sauté the curry paste for 3 minutes. Stir in the coconut milk, salt, palm sugar, and fresh lime juice. Heat the sauce but do not boil or it will curdle. Add the vegetables to the pan, toss together till well combined and adjust the seasoning. Serve over steamed rice.

Serves 4 to 6.

Vegetable Tempura

Tempura is a classic Japanese presentation and when done well is delightfully light and crunchy. Unlike most Japanese dishes, this is a meal that should be served piping hot. Note: I’ve listed some of my favorite vegetables for tempura. Other vegetables, such as broccoli, yard-long beans, bell peppers, bamboo shoots, daikon radish, and snow peas can also be used.

You will need a heavy deep pot for frying; a slotted spoon for lifting the fried foods out of the oil; a platter lined with paper towels to drain the fried vegetables; and a pair of long, wooden chopsticks (called cooking chopsticks) to dip the vegetables in the batter.

For the batter:

1 egg yolk

1 cup ice water

1 to 1¼ cups sifted cake flour

1 pinch baking soda

For the tempura vegetables:

1 thin Japanese eggplant, sliced ⅛ inch thick

1 carrot, sliced into thin coins on the oblique

1 zucchini, sliced ¼ inch thick on the oblique

½ sweet potato, peeled and sliced about ⅛ inch thick

8 fresh, small button mushrooms

8 slices of winter squash, peeled and sliced about ⅛ inch thick

Perilla leaves

Shungiku leaves

For the dipping sauce:

1 cup dashi (see the recipe on page 73)

3 tablespoons soy sauce

3 tablespoons mirin

Pinch of salt

For the condiments:

½ cup peeled, grated white daikon radish

2 teaspoons grated fresh ginger root

Lemon wedges

To make the batter: With a fork, combine the egg yolk with the ice water in a small bowl. The batter should be the texture of heavy cream; just thick enough to coat the vegetables. Just before frying the vegetables, stir in the flour and the baking soda, beating just long enough to combine without overworking the batter.

To make the tempura: The key to good tempura is as follows: use only fresh vegetable oil.

The oil should be at least 3 inches deep. The ideal frying temperature for vegetables is 320°F to 340°F. To test, drop a bit of batter into the oil. It should drop to the bottom and then rise slowly to the surface. Be careful not to overheat the oil; if the oil smokes, it is too hot. Do not crowd the pot; for best results less than half the oil surface should be covered with vegetable pieces. Have all your ingredients at hand and arranged in the order that you will use them.

Preheat the oven to warm, about 200°F. To cook, coat each vegetable piece with the batter and fry for one minute. With the chopsticks turn the pieces and fry for another minute until the pieces are golden and puff up. Drain the vegetables on the paper towels and skim crumbs from the oil using a metal slotted spoon. Place the vegetable slices on a warm platter and keep them in the oven until you are done, or better yet, serve each piece to your guests as they come out of the oil. Repeat the process with the other vegetables.

To serve the tempura: Make the sauce by heating the dashi, add then stirring in the soy sauce, mirin, and salt. As is traditionally done in Japan, provide each diner with a shallow bowl of the warm dipping sauce, to which they can add grated daikon and ginger to taste. Serve the tempura accompanied by the lemon wedges.

Serves 4.