7

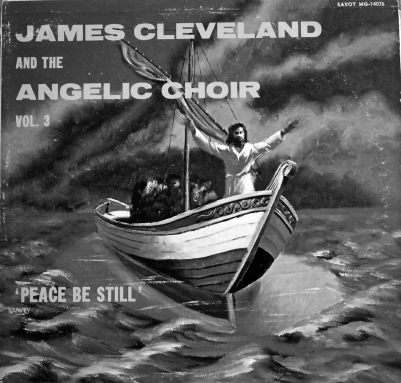

Peace Be Still

If you didn’t know that the tall, rectangular, nondescript brick edifice on Hillside Avenue once housed Trinity Temple Seventh-day Adventist Church, you might think it is a gymnasium, a community center, or perhaps a banquet hall. Once inside, however, you realize it is a sacred space—unassuming, but sacred nevertheless. Dark wooden-paneled wainscoting adorns the walls and surrounds the slightly raised wooden altar. The altar is tiered in the back to accommodate a small choir. This is where the Angelic Choir stood to sing for Sunday worship and on Thursday evening, September 19, 1963, for their third Sunday Service recording session with James Cleveland.

A special schedule of preparatory rehearsals for the session was announced during First Baptist Sunday services in late August and early September. The Angelic Choir—now numbering between sixty and seventy-five members—began studying the songs they would record. “My husband would go over the songs with the choir before James would come,” Bootsy said, “and then James would rehearse [with us] all week long. [James] would come and stay with us. He was like a brother. He put a bathroom in our house upstairs.”1

Robert Logan remembered it like this: “James Cleveland would come to town and we’d have maybe one or two rehearsals, and they’d sometimes last hours and hours. He’d start at seven or eight at night and you’d be out until twelve o’clock, because he was a perfectionist. People who have a great gift in them want to do everything to a T. And we should do it to a T to please the Lord.”2 “We only had about, I’d say, four rehearsals,” Inez Reid recalled. “We didn’t have that many rehearsals because Reverend James Cleveland and Reverend Roberts were just that good with music. It didn’t take us long to learn a song.”3 For Reid, who had never heard “Peace Be Still” before the September rehearsals, learning it was relatively simple because Cleveland and Roberts took time to teach each section of the choir—soprano, alto, and tenor—its part.4 “Reverend James Cleveland said it was nice to work with us because it wasn’t hard to teach us songs,” Reid said. “We caught on so fast.”5

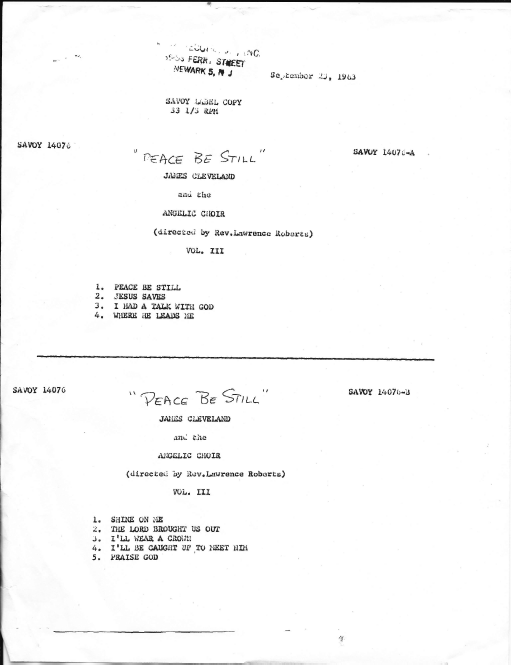

Although the first two Sunday Service sessions were literally held on Sundays, Peace Be Still was scheduled for a Thursday evening. Recording on a Thursday at Trinity Temple was so odd that, decades later, Bootsy Roberts questioned whether the date in Savoy’s session book may have been given in error. She distinctly recalled Sundays being the only day in the week Trinity Temple was available for their use.6 Complicating the dating further, producer Fred Mendelsohn told Viv Broughton that the recording happened on a Sunday because Trinity Temple “was the only church not already in use on a Sunday.”7 This dating holds up logically, and Bob Porter, who helped compile the Savoy discography, believes that “If Fred said it was Sunday, it was Sunday.”8 On the other hand, Robert Logan, whose mind is sharp and his memory lucid, insists without the shadow of a doubt that not only did the Peace Be Still recording take place on a weekday—in his recollection, it was either a Thursday or Friday—but that it was held in the evening.9 Musicians Union payment stubs for the instrumentalists would help break the tie, but none can be found. And because the album was not recorded in a commercial studio, there are no documents detailing the session—take numbers, personnel, dates, times, and so on.

The numerical order of matrices assigned to selections that Savoy recorded in September 1963 is not necessarily helpful, either. The matrix numbers immediately following Peace Be Still (63–287 to 63–298) were assigned to a Wednesday, September 25, Imperial Gospel Singers session date even though, chronologically, the Southwest Michigan State Choir of the Church of God in Christ recorded for Savoy four days earlier, on Saturday, September 21.10 That the September 21 recording was made offsite in Detroit likely accounts for the fact that it was assigned higher matrices than the locally produced Imperial Gospel Singers session, which probably was entered into the log immediately after the session took place. The accuracy afforded these session dates, notwithstanding the matrix order, also argues for September 19 as the recording date of Peace Be Still.

Assuming, then, that the recording date was indeed Thursday, September 19, the shift from Sunday to Thursday might have been to accommodate Cleveland’s schedule of singing appearances. Having accepted Annette May Thomas’s invitation to serve as music minister and choir director at New Greater Harvest Baptist Church in Los Angeles, he would have needed to be back on the West Coast in time to lead the music for Sunday service.11 Possible, but not convincing, in that his commitment to the New Greater Harvest music ministry didn’t stop him from traveling later in the 1960s, and his frequent unavailability eventually cost him his church assignment. On the other hand, that the Cleveland Singers were present on Peace Be Still suggests the troupe was touring the area with their leader and may have been engaged to appear at a local church that Sunday. Whatever the reason, if Cleveland was in town, Savoy would have wanted to eke every ounce of utility out of him before he returned to the West Coast.

Notwithstanding the mystery surrounding the recording date, everyone interviewed for this book who participated in the Trinity Temple recording session that September evening recalled the church being full to capacity. Who was there? “Everybody” remembered Reid, “and not only church members [but] our friends that didn’t belong to that church. It was just a fully packed church.”12 Deacon Raymond Murphy remembered the entire recording session taking “just a couple of hours, but it was like a service. You weren’t there because it was a recording. We were there having service. It was just recorded as a service.”13 Fred Mendelsohn’s recollection of the session aligned with those of the choir members. “We got the crowds and it was a piece of magic,” he told Broughton. “There too, you could feel the excitement running high and that’s what makes an album. The inspiration was there.”14

The “excitement running high” at the session made it an oasis in a time of national tragedy. Four days before the recording session, on Sunday, September 15, 1963, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, was the site of a racially motivated bombing that took the lives of four young members: Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Denise McNair. Among the twenty others injured was ten-year-old Sarah Collins, who lost an eye in the blast. Tensions in the wake of the bombing spilled out into mass protests on the streets of Birmingham, leading to more deaths when protestors and police clashed. The incident—the latest in a string of bombings in Birmingham—stimulated international outrage and contributed to the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

But the Angelic Choir members interviewed for this book who were present for the Peace Be Still session did not recall that the Birmingham tragedy affected either the mood of the title track or the spirit of the session. As Bernadine Hankerson recalled, the atmosphere at Trinity Temple was “very spiritual. We wasn’t [so] disturbed [by the news] that we couldn’t serve the Lord. We knew the Lord and we were there to praise and lift up His name. That was the purpose. So anything that happened anywhere else, we were just there to praise the Lord and thank Him that we were able to make it.” She added, “We knew [the bombing] had happened but it wasn’t ruling life.”15 And although some African American churches took precautions after the Birmingham bombing to make sure a similar incident would not happen on their premises, none of the Angelic Choir members was concerned about personal safety at Trinity Temple. “If they had any concerns,” Murphy noted, “they kept it to themselves.”16

If producing the first two volumes of the Sunday Service collaboration went more or less according to plan, the third volume turned out to be a challenge. Engineer Paul Cady, now experienced in wiring First Baptist Church for sound, had to recalibrate his learning to accommodate the cavernous Trinity Temple. Running wires from the mobile recording truck parked on Hillside Avenue to the microphones in the church, he and Roberts positioned the featured soloists on one microphone, sopranos on a second microphone to intensify the treble sound, and a third microphone for altos and tenors. Roberts miked the organ, piano, and drums; placed a shield around the drums to stop its sound from bleeding into the other microphones; and draped a heavy cushion or blanket over the piano for the same reason.17

Another, and more significant, challenge was finding musicians for accompaniment, for Thurston Frazier and Billy Preston, critical contributors to the first two volumes, were unavailable. Frazier’s absence may have been due to his hospitalization at the time. Since Savoy did not list the personnel on the back cover of Peace Be Still, as it had done on the prior two volumes, the identity of the three-piece band for the session has been a source of speculation. Members of the Angelic Choir interviewed for this book better remembered which musicians did not play on the session than those who did. The consensus was that neither James Cleveland nor any of the Angelic Choir’s regular musicians were on piano, organ, and drums. Gertrude Hicks, the choir’s chief piano accompanist, admitted she “wasn’t good enough” at the time to play on a recording.18 The drummer is assumed to be Joe Marshall, because he played on the other live albums and was a Savoy studio stalwart in the early 1960s. Herbert “Pee Wee” Pickard was offered as one possibility as organist, but Pickard told this author he “did not play one note on Peace Be Still.”19 When the question was posed to gospel music historians and enthusiasts familiar with the period, suggestions ranged from Charles Barnett of the Cleveland Singers to Charles Craig of the Voices of Tabernacle. But musicians pay attention to other musicians, and without missing a beat, the organist Robert Logan recalled who was on keyboards: John Hason on piano and Doctor Solomon Herriot on organ.

Born in 1942, John Wesley Hason Jr. had a storied through tragically short career with James Cleveland. He was skilled on both piano and organ and, according to Logan, was traveling with Cleveland at the time. Hason can be heard playing piano on the Cleveland Singers’ May 1963 Savoy session, which produced the first recorded version of “I Had a Talk with God,” a song also on the Peace Be Still playlist. His résumé would include multiple recording credits on albums produced under Savoy’s James Cleveland Presents series and on albums on the Atlantic and Zanzee imprints by the Institutional Church of God in Christ Choir of Brooklyn, New York. Hason also formed his own small group, the John Hason Singers; they recorded a single for Savoy’s Gospel subsidiary in 1965 and a full album in 1975.20 He is known to a wider audience for his on-screen role as the accompanist for the choir in the church scene from the 1980 film The Blues Brothers. At the time of his death in 1987, Hason was a musician for the Victory Temple Church of God in Christ in San Francisco.

Born June 16, 1936, in New York,21 Doctor Solomon Herriot Jr. may seem at first blush as a most unusual choice to play organ on this session, in that his musical training was honed in the classical world. According to a brief biography from a program of his music, Herriot began piano lessons in 1946 with Vereda Pearson and organ lessons three years later with Doctor Lawrence F. Pierre. He attended Mannes College of Music, the Juilliard School, and Guilmant Organ School. He continued his organ studies under the tutelage of Hugh Guiles, Edgar Hilliard, Bronson Ragan, and Virgil Fox. He also studied choral conducting with Richard Weagley of Riverside Church and William Whitehead of Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church. In October 1961 he was named head organist and choirmaster at New York’s Mother African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church.22

Nevertheless, Herriot made a few forays into gospel. For example, he accompanied Lillian Hayman and the Messengers on their 1961 gospel album for Richard Simpson’s eponymous label.23 Simpson engaged Herriot as organ accompanist for sides by the Richburg Singers, also released on his own label, and on a 1964 album produced for Vee Jay Records. Herriot accompanied the Gospel All-Stars on a 1964 album called Deep River for the Gospel Recording Company (not the Savoy subsidiary) and directed the Mother AME Zion Choir on a 1968 Fantasy Records recording of Duke Ellington’s Second Sacred Concert. In 1976 Herriot helped install Mother AME Zion’s new pipe organ.24 Despite Herriot’s robust classical training, the Reverend Dr. Malcolm Byrd, current pastor of Mother AME Zion, who knew and worked with the organist, called him “a gospel musician who turned classical.”25 Byrd remembered Herriot as somewhat of a loner but someone who also garnered considerable respect throughout the community and was often referred to as the dean of black church music. What with Herriot’s musical bona fides, it’s no surprise he was engaged for the session when Preston was unable to participate. “Everyone in Harlem knew he played on Peace Be Still,” Byrd said.26

With everyone ready—the choir behind the altar, the musicians miked, and Cady satisfied with the audio arrangement, the session commenced. To capture the atmosphere of the evening effectively, the following song- by-song description reports the order of the program as recorded, not as configured on the final album. I am indebted to Doctor Braxton D. Shelley of Harvard University for his inestimable assistance in explaining the music theory behind each selection.27

“Jesus Saves”

“Jesus Saves,” an original James Cleveland song sung in D-flat at a moderate tempo, was the first selection committed to tape on the evening of September 19.28 Hebrews 7:2529 informs the lyrics: “Wherefore He is able also to save them to the uttermost that come unto God by Him.” The lyrics also borrow from Psalm 40:2: “He brought me up also out of an horrible pit, out of the miry clay, and set my feet upon a rock, and established my goings.” An indirect influence is the refrain to “He Brought Me Out,” a hymn written in 1898 by Henry J. Zelley (1859–1942). It begins with “He brought me out of the miry clay / He set my feet on the Rock to stay.” Popular gospel songs of the era, such as Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers’ 1954 single, “Jesus I’ll Never Forget,” employed the “miry clay” analogy to depict deliverance from difficulties.

As he did on the previous Sunday Service volumes, Cleveland assumes the role of chief minstrel. He introduces nearly all the songs with a brief narrative delivered authoritatively in his trademark rasp. For “Jesus Saves,” Cleveland introduces what would become the album’s salvation motif: “I know tonight for myself that Jesus saves, yes he does. I’d heard about it for a long time, but one Tuesday evening fourteen years ago, I learned it for myself. And I can tell you tonight he’ll be to you just what you let him be.”

After the introduction, Cleveland and an uncredited male vocalist (possibly Roberts) sing a duet in two-part harmony while the choir answers with the melodic response “Jesus saves, Jesus saves.” Later, the tables turn and the choir assumes principal responsibility as Cleveland and the male vocalist trade interjections. Then, out of nowhere, a female singer enters the fray, shouting “to the utmost” and “he’ll turn you around,” following each with gut-wrenching “yeahs.” The compound triple 9/8 beat, known colloquially as the “rocking chair” rhythm because it simulates the fluid motion of a rocking chair, is accentuated by Marshall’s percussive drumming as the choir and musicians juggle alternating crescendos and diminuendos. For Shelley, Cleveland’s juxtaposition of piano and forte, or quiet and loud choral sounds, likens the use of the choir “as an almost orchestral instrument.”30 Cleveland would employ this juxtaposition, or use of the choir as instrument, again on “Peace Be Still.”

After the Angelic Choir sings multiple lines of “To the utmost / Jesus saves,” the musicians drop off temporarily. Cleveland breaks the silence by announcing: “This is how the old church did it.” Reprising the technique he used on How Great Thou Art’s “He’s All Right with Me,” Cleveland alters the tempo from 9/8 to duple meter and leads the Angelic Choir on a feverish, hand-clapping, sanctified-church-style rendering of the chorus, centered on a sung “Hallelujah”—a kind of vamp, notes Shelley, with harmonies in E-flat and B-flat.31 Although to the listener the shift appears spontaneous, Gertrude Hicks recalled that any such techniques were rehearsed beforehand: “We had a sense of direction of where we were going.”32 A keen ear can hear a split-second tape edit immediately after Cleveland’s comment, possibly to eliminate unwanted silence or errors made by choir members or musicians during the tempo change.

As this special section pulses along, with the choir clapping on the backbeat and singing at a thunderous volume, Cleveland begins rapping tunefully on a variation of his opening remarks on salvation: “Ain’t but one thing I’ve done wrong / Stayed in sin just too long / God in my hands / God in my feet / Made my joy so complete.” The energy dissipates around the eight-minute mark, giving the choir a moment to cool down and Cleveland a chance to tee up the finale, which he does by using the chorus as lyric fodder. “One day I was so filthy and unclean / I was in the gutter of life. What did he do for you, Brother Cleveland? He picked me up, yes he did, yes he did, yes he did.” He finishes by shifting the musical time to rubato, declaring, “And if they let me in the White House tonight, and they wanted somebody to be a witness for him, I could lift my hands and say, ‘Hallelujah! Jesus saves!’” With this, Cleveland and the Angelic Choir conclude. Shelley points to Cleveland’s thrice changing of musical time as among the song’s most interesting characteristics.33

With a running length of nearly ten and a half minutes, “Jesus Saves” was among the longest gospel song presentations committed to vinyl by that point. The length gave listeners unfamiliar with the rhythm and spirit of African American gospel music a chance to hear the dramatic ebbs and flows, the dynamic peaks and valleys, play out over a period longer than radio play permitted. It also demonstrated a technique, now ubiquitous in gospel music, of starting a selection by singing in a subdued manner, then building the song’s intensity to an emotional climax, and liberating the tension through a gradual cooling down to the conclusion. Indeed, what made this and all the Cleveland-Angelic Choir Sunday Service collaborations distinctive was that listeners from every walk of life, including those who might never set foot in an African American church, experience how hymns and gospel songs were performed in front of a congregation, in an authentically reconstructed African American prayer or revival service.

Since its introduction on Peace Be Still, “Jesus Saves” has been covered in whole or in part by a number of gospel artists, such as Cleveland protégés Jessy Dixon and the Gospel Chimes (1965); Doctor Charles G. Hayes and the Cosmopolitan Church of Prayer (1982); the Voices of Victory of the Salem Baptist Church of Omaha, Nebraska, with the Reverend Bruce Parham on lead (2001); and Luther Barnes and the Sunset Jubilaires’ 2003 gospel quartet interpretation. Douglas Miller’s 1985 solo version of “Jesus Saves” was fully Pentecostal-flavored. Moreover, artists from Daryl Coley to the Edwin Hawkins Music and Arts Love Fellowship Conference Mass Choir have incorporated lyric snippets such as “To the utmost, Jesus saves,” and “He will pick you up and turn you around” into their arrangements. Likewise, the miry clay imagery in gospel song persists through such selections as the Newsboys’ 1991 “Kingdom Man” and 2004’s “For All You’ve Done,” by the internationally popular Australian Christian worship band Hillsong.

Perhaps the most popular cover came in 1984, when Little Cedric and the Hailey Singers recorded “Jesus Saves” for GosPearl Records. The song catapulted the album of the same title to number four on the Billboard Top Gospel Albums chart and helped make the teen gospel quartet GosPearl’s top-selling artist of the mid-1980s.34

“Peace Be Still”

“Peace Be Still” is based on Mark 4:37–39: “And there arose a great storm of wind, and the waves beat into the ship, so that it was now full. And [Jesus] was in the hinder part of the ship, asleep on a pillow: and [the disciples] awake him, and say unto him, ‘Master, carest thou not that we perish?’ And he arose, and rebuked the wind, and said unto the sea, ‘Peace, be still.’ And the wind ceased, and there was a great calm.”

The hymn’s melody comes from “Master, the Tempest Is Raging,” composed in 1874 by Doctor Horatio Richmond Palmer (1834–1907), who also composed the popular gospel hymn “Yield Not to Temptation,” and its lyrics come from a song text written by Mary Ann Baker (1831–1921), a Baptist and temperance-movement supporter who lived in Chicago. The composition came about when Palmer, music director of Second Baptist Church, then located at Monroe and Morgan Streets on Chicago’s Near West Side, asked Baker, a Sunday school teacher at Second Baptist, to set some biblical stories to song texts that could be used in a series of Sunday school services. According to historian and author Karen Lynn Davidson,

Mary Ann Baker was left an orphan when her parents died of tuberculosis. She and her sister and brother lived together in Chicago. When her brother was stricken with the same disease that had killed their parents, the two sisters gathered together the little money they had and sent him to Florida to recover. But within a few weeks, he died, and the sisters did not have sufficient money to travel to Florida for his funeral nor to bring his body back to Chicago.

Of this trial Baker said, “I became wickedly rebellious at this dispensation of divine providence. I said in my heart that God did not care for me or mine. But the Master’s own voice stilled the tempest in my unsanctified heart, and brought it to the calm of a deeper faith and a more perfect trust.”35

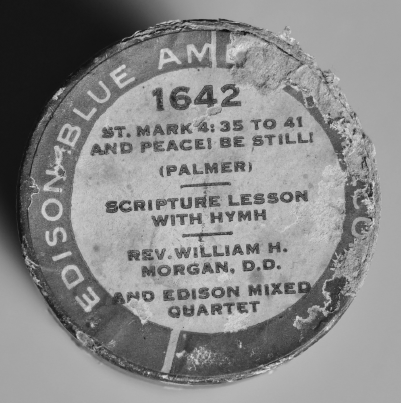

Palmer published their composition in 1874 in his Songs of Love for the Bible School hymnbook.36 By 1881 the hymn was sufficiently popular that it was sung at several funeral services held for assassinated US President James Garfield.37 The first known commercial recording of the hymn was made by the Edison Phonograph Company in December 1912. Released in March 1913 on a Blue Amberol cylinder, the recording opens with a solemn reading of Mark 4:35–41 by the Reverend Doctor William H. Morgan.

Born in Whiton Park, England, in 1861, William Morgan emigrated to the United States with his parents in 1870. The family settled in Ironton, Ohio, and, at age eleven, Morgan took employment with the Iron and Steel Works. In 1883 he entered Ohio University but left after two years and enrolled at the Hamline College of Minnesota, where he graduated in 1889. He continued his studies in New Jersey, at the Drew Theological Seminary in Madison, and, as a student, pastored a church in Port Morris. In 1897 Morgan accepted the pastorate of the Central Methodist Episcopal Church in, of all places, Newark, New Jersey. It was during his tenure in Newark that he recorded the four-minute Edison cylinder. After a windy organ introduction, the Edison Mixed Quartet, a mixed-voice group probably composed of Elizabeth Spencer, Cornelia Marvin, Harry Anthony, and Donald Chalmers, follows Morgan’s recitation with a faithful a cappella rendition of Palmer’s “Master,” titled for the cylinder release as “Peace! Be Still.”38 Morgan went on to record several more religious cylinders for Edison from 1913 to 1921, all of them featuring his recitation of scriptural passages with choral or quartet singing afterward.

The arrangement of “Peace Be Still” that Cleveland taught the Angelic Choir in New Jersey in 1963 originated on the other side of the nation, in Los Angeles, California, a few years prior. One day, leafing through his copy of the Broadman Hymnal, as he liked to do from time to time, the Reverend James Ewell stopped at number 471, “Peace Be Still.” He thought it might make a great arrangement for a gospel choir.

An amateur hymnologist, Ewell was born to a sharecropper family in Dermott, Arkansas, on February 25, 1924, and raised in nearby Augusta, Arkansas.39 In 1944 he migrated from Arkansas to Los Angeles, where he joined Reverend John Branham’s St. Paul Baptist Church, the same church whose Echoes of Eden choir recorded for Capitol Records. Participating in the church’s music ministry, Ewell sang “Standing in the Safety Zone” to open the church’s Sunday radio broadcast.

At some point in the 1950s, the Reverend William H. Wofford, assistant pastor of St. Paul and a fellow transplant from Arkansas, moved to Bethany Baptist Church. Ewell went with him. Gwendolyn Cooper Lightner became Bethany Baptist’s music minister. Born in rural Brookville, Illinois, on June 28, 1925, Lightner took piano lessons while in elementary school and continued her music studies at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale and at Chicago’s Lyon and Healy Academy of Music.40 Although skilled in the western European classical music repertory, Lightner became fascinated with gospel music. She sought out Kenneth Morris, a composer and publisher who had served as minister of music and organist at Chicago’s First Church of Deliverance in the late 1930s. Morris, who introduced the Hammond organ to First Church of Deliverance and, via its Sunday evening radio broadcast, to churches throughout the country, helped Lightner incorporate the bounce of gospel music into her keyboard technique.41

At Reverend Branham’s invitation, Lightner moved from Chicago to Los Angeles in the early 1940s to accompany the Echoes of Eden.42 With National Baptist Convention wunderkind J. Earle Hines (1916–60) directing the choir and soloing, Sallie Martin and her adopted daughter Cora assisting, and Lightner on piano, the Echoes of Eden became popular through its broadcasts over radio station KFWB. Soon, celebrities like actress Jackie Beavers were showing up at St. Paul to enjoy Branham’s sermons and the spirited singing of the Echoes of Eden.

In 1957 Lightner and Thurston Frazier organized a community choir called the Voices of Hope to perform for a March of Dimes charity event. The choir was so well received by the public that its members, one of whom was Reverend Ewell, wanted to keep it going. It was for Bethany Baptist Church as well as for the Voices of Hope that Lightner arranged “Peace Be Still.” The Voices of Victory, which released the 1954 in-service disk under the direction of Thurston Frazier, learned it from them. “My father was always looking for new hymns to learn and sing,” Melodi Ewell Lovely, Ewell’s daughter, a musician in her own right, recalled. “He took [‘Peace Be Still’] to Gwen and asked her to play it for him. From there, they basically arranged it as a gospel song.”43

“Peace Be Still” began to spread beyond Bethany Baptist and the Voices of Hope. Singer-songwriter Joe Peay, founder of the Triumphs gospel group, remembered hearing the arrangement sung by the Voices of Victory on Sunday radio broadcasts from Los Angeles’s Victory Baptist Church, pastored by the Reverend Arthur Atlas Peters. Peay described his first encountering of the arrangement:

I arrived in L.A. in 1962. A local church radio choir [Voices of Victory] was singing “Peace be Still” on their [radio] broadcast. They did a marvelous job. Firstly, a gentleman would come on and narrate the encounter of Jesus Christ on that ship. That’s what got my attention. The guy did such a phenomenal job on it. He would do this every Sunday for the radio broadcast. When I became friends with Thurston Frazier, I asked him who wrote the song. He showed me the hymn book it was in.

Soon thereafter, Thurston invited [the Triumphs] to appear on a television program with his community choir. He taught the choir “Peace be Still.” I always recognized James Cleveland as an opportunist, so after the first rehearsal, I said [to Frazier], “I’ll bet your friend James Cleveland will take that song and record it and make a hit out of it.” Those are the very words that came out of my mouth. A few months later, the record was released by Savoy. James changed the arrangement somewhat, and the rest was gold.44

Cleveland had moved to Los Angeles by 1962, when the Voices of Victory’s “Peace Be Still” could be heard on radio. As a friend and associate of Frazier—the two would form a gospel music publishing partnership called Frazier-Cleveland and Company45—he would have been aware of Lightner’s arrangement, if he hadn’t heard it from Lightner herself. Still, by September 1963, neither the Voices of Victory nor the Voices of Hope had recorded her arrangement.46 That left the door wide open for Cleveland, who never saw an open door of opportunity he didn’t stride confidently through.

“At one time, Thurston Frazier and the Voices of Hope would sing ‘Peace Be Still,’” Annette May Thomas said. “[Reverend Cleveland] liked it so much that he went on and recorded it. We always liked Gwendolyn Cooper Lightner’s intro to it, the little piano run she always did. When Reverend [Cleveland] recorded it, he used that same run. That was her arrangement. I think they were a little upset, but James liked it and he recorded it. But he was able to record it. It wouldn’t have gotten the publicity it got if Reverend Cleveland hadn’t recorded it. What he did was similar, but different.”47 Melodi Lovely said her father “was never bothered by the fact that he wasn’t acknowledged as being an arranger of the hymn,” Lovely said. “If it did, he never expressed it, not to me. I never heard him express it.”48

In Hason’s hands, Lightner’s piano introduction to the Angelic Choir’s “Peace Be Still,” coming as it does after the alternately relaxed and rollicking “Jesus Saves,” signals that the mood is about to change. The opening is sweetly somber—no James Cleveland spoken introduction (if he did one, it wasn’t recorded), rapt silence from the congregation, just Hason and organist Herriot introducing the song with intense harmonic flourishes, echoes of the subdued instrumental introduction of the Gospel Clefs’ “Open Our Eyes.” Marshall’s light brushing of the toms and cymbals are meant to evoke the sound of churning waves and distant thunder.

With an unhurried 9/8 gospel waltz tempo firmly established,49 Cleveland’s first sung word, master, is a calm but firm attempt to rouse the sleeping Jesus. Its veiled power is said to have thrilled author James Baldwin, who told Anthony Heilbut that Cleveland “could kill him with the simple reading of ‘Master.’”50 Cleveland rests for two beats, then a keen awareness of the advancing waves drives him to an anguished plea of unnerving sonority: “The TEMPEST is raging!” When Cleveland stretches out the word tempest to give it sufficient gravitas, he does so on his top note, which in his sandpaper-rough voice adds a frightened urgency to his cry, as if he were literally staring down the naked power of a quickly approaching storm and wondering whether it might already be too late. Spiritually aroused by Cleveland’s ferocious reading, several congregants and choristers, Ernest Nunnally most audibly, respond with interjections of admiration and encouragement.51

By opening with a vocal solo instead of choral singing, as the Voices of Hope had done, Cleveland transforms the disciples’ communal plea for salvation into a personal entreaty. He concludes the section with a direct plea, “Get up, Jesus!” a now almost compulsory exclamation for covers of “Peace Be Still.” “James did a tremendous job of transforming [“Peace Be Still”] from the exclusive choir format by placing in it a solo,” Peay observed. “I don’t know if somebody told him to do that, or Thurston [Frazier] advised him, or James did it himself, but James created that solo part, which really set the ball off in another direction.”52

Meanwhile, Marshall’s insistent 9/8 tempo, now sounding like war drums galvanizing a military regiment for battle, portrays in percussion the impending clash between the Savior and the storm. The Angelic Choir enters as anxious witnesses, as if standing on the shore near the ensuing action. The choir raises the sonic tension incrementally, its staccato cadence itself a form of military tattoo: “Whether the wrath of the storm-tossed sea / Or demons or men or whatever it be / No water can swallow the ship where lies / The Master of ocean and earth and skies.” At the words “They all,” the tautness created by their voices in cacophonous communion reaches its apogee in a thunderous chord and then abruptly drops into silence, the crashing waves halted by the command of Jesus. The force calmed, the choir whispers the line “sweetly obey Thy will.”

The choir’s sudden plunge from fortissimo to pianissimo elicits a cacophony of gleeful endorsements from the choir and, presumably, some in the live audience.53 It marks out a dramatic arc, Shelley notes, which parallels the escalation of an approaching storm—heightening the tension to a breaking point and then releasing it as Jesus speaks “Peace! Be still!”54 But Cleveland is just getting started. He directs the choir to reprise the segment, but this time, he interjects the lyrics like a preacher in full rapture, raising the intensity alongside the group and joining them on their second free fall, prompting another round of spontaneous exhortations of admiration. Where the Palmer-Baker original climaxes once, the Cleveland–Angelic Choir arrangement climaxes twice, in keeping with Lightner’s arrangement.55 To historian Will Boone, repeating the climactic moment of the song is more than just a musical technique; it’s a “musical declaration of the phrase so common among black Sanctified and Pentecostal believers—‘if He did it once, He can do it again.’”56

“I thought it was fantastic the way we modulated up high and then came down low,” Bootsy recalled of this section of the song.57 Pearl Minatee’s daughter, the Reverend Doctor Stefanie Minatee, thought so, too. “I think the choir climbing to [the word] peace really has something to do with [the song’s popularity]. They don’t stay on the same plane; the choir climbs.”58 Veteran gospel announcer Linwood Heath also points to this technique as one of the reasons the song became popular. “To bring you up and then come down, there was something about it that was just—we hadn’t heard that in Philadelphia. And then when they came down sweetly [on] ‘Sweetly obey thy will,’ it just really touched your heart. I believe it was God’s doing. It just ministered to people and it was something unique about it, something that just hit us when we heard it.”59

To Marshall’s persistent pulse and punctuations from Hason’s piano and Herriot’s organ—at one point, Herriot simulates thunder with a rapid arpeggio—the ensemble finishes the six-minute scene by reversing the antiphonal effect, as they did during “Jesus Saves.” The choir now leads and Cleveland, whose pleas opened the piece, is the respondent. For every sung utterance of peace by the choir, Cleveland shouts “Yes!” as if answering the voice of God during a moment of religious ecstasy. The song fades to an end peacefully, calmly, the wind and the waves having subsided and the disciples now safe.

“Peace Be Still” is spectacular sacred theater. It raises gospel music to new heights of artistic accomplishment and, as Professor Johari Jabir notes, serves as “a bridge between the early folk/blues style of gospel and the soulful sound of gospel inspired by modern jazz, pop, and soul.”60 Like the Gospel Clefs, James Cleveland and the Angelic Choir foretell the coming of the contemporary gospel music movement six years before Edwin Hawkins’s “Oh Happy Day” made the transition official. Skillful editingroom technique by Roberts ensures that the 9/8 tempo of “Peace Be Still” and snippets of its motive, played reflectively on piano and organ, bleed seamlessly into Cleveland’s oratorical introduction to “Jesus Saves.”

Whether planned or not, reversing the order of “Jesus Saves” and “Peace Be Still” on the album makes narrative sense. “Jesus Saves” is a celebration of Jesus’s redemptive power. It exemplifies the awe expressed by the disciples, who exclaim, “What manner of man is this?” in the passage in Mark immediately after Jesus’s actions. On the other hand, “Peace Be Still” describes Jesus’s act of intervention that prompted such praise and gratitude. Reversing the two places the miracle and the gratitude in the proper order. But in actuality, it was probably a commercial decision. The track to highlight was made manifest by the enthusiastic response from the choir and live audience. Shelley’s 2017 article on how a lead single was selected from a live album by gospel artist Richard Smallwood is instructive: “In the live recording, audience members become affective laborers whose praise serves to sell and—one might add—sanctify new sonic materials…. The performance of previously unheard compositions must be met with a certain response if it is to be accepted as commercially viable.”61 Employing this argument, one can infer that the audible appreciation for “Peace Be Still” by the choir and live recording audience was sufficient for Cleveland, Roberts, and Mendelsohn to make it the album’s lead single. Since Gwendolyn Lightner’s arrangement of “Peace Be Still” was unknown to Angelic Choir members until they rehearsed it, and completely unknown to most members of the live audience—the “affective laborers”—until they experienced it that September evening, the interjections during the live recording could be likened to the reaction of an informal and uncompensated focus group. Even though the choir rehearsed the song, those anticipated but nevertheless spontaneous improvisatory elements that give every gospel song performance its own DNA kept things fresh and somewhat unexpected. The reactions gave Savoy the feedback it needed to select “Peace Be Still” as the radio single.

Since radio preferred programming songs around three minutes in length, the six-minute “Peace Be Still” had to be divided into two parts for the 45-rpm disk. Savoy was already familiar with this practice, having divided the Ward Singers’ lengthy 1953 single, “I Know It Was the Lord,” into two parts. But it is likely that a preference for hearing and, in some instances, programming the song on radio in its entirety, without the distracting interruption of flipping over a 45-rpm disk, contributed to the overwhelming sales of the Peace Be Still album, where the performance could be heard without interruption.

“I Had a Talk with God”

Gerri Griffin sat patiently with her parents in the basement of Trinity Temple, waiting to be summoned to the main sanctuary. She had just celebrated her eleventh birthday two days earlier, but Gerri was no newcomer to musical performance. She had sung in front of church congregations since the age of two. But being selected personally by James Cleveland to solo on “I Had a Talk with God” could be the budding talent’s chance for national exposure.

Born in New York on September 17, 1952, Geraldine Griffin was the second of four children of Herbert “Chuck” Griffin and Anna Quick Griffin.62 The family resided at 2224 Second Avenue in East Harlem’s Thomas Jefferson Homes.63 Anna had been a member of the Daniels Singers, a New York gospel group that sounded like a sanctified version of the Roberta Martin Singers. Chuck was a community organizer who formed a nonprofit to offer economically disadvantaged East Harlem youth a variety of positive out- of-school activities—from sports to singing. A student at East Harlem’s PS 57, Gerri channeled her irrepressible energy into singing folk songs, writing poetry, and playing piano. A fan of South African singer Miriam Makeba, Gerri knew from an early age that she wanted to pursue music professionally. Though the family was raised Methodist, they attended Grace Temple Church of God in Christ because Gerri’s uncle, the Reverend Norman Nelson Quick, was its pastor. Gerri sang at Grace Temple and became the unofficial mascot of the church’s basketball team.64

Gerri couldn’t have asked for two better career advocates than her mother and Bernice Cole (ca. 1921–2006). Like Anna, Bernice was a national gospel recording artist. Around 1951, she joined the Angelic Gospel Singers, a female gospel group from Philadelphia that had scored a national hit with their debut single, “Touch Me Lord Jesus.” Bernice sang with the Angelics until 1957 and returned to the group sometime in the mid-1970s. Both Bernice and Anna had deep tentacles in the East Coast gospel music community, both were resourceful, and neither was shy, especially when it came to promoting Gerri’s talent. “My mother never ceased to amaze me how industrious and resourceful she was when it came to making and creating opportunities for me,” Gerri recalled. “Bernice was as big an advocate for me as my mother was.”

In 1963 Cole learned through the church grapevine that James Cleveland was scheduled to appear at Mount Moriah Baptist Church in Harlem. She and Anna decided to attend the Mount Moriah program, Gerri in tow, and to see whether they could persuade Cleveland to give Gerri an informal audition. “They wrangled a solo for me at that [Mount Moriah] service,” Gerri said. “They had to find a box or something for me to stand upon, to reach the microphone at the podium, because I was so young and small.”

Gerri sang “Somebody Bigger Than You and I” for Cleveland and the Mount Moriah congregation that day. “I never got emotional when I sang before,” she said, “but I guess I kind of got that it was important, or whatever it was, and … I remember hitting the last notes of that song and starting to cry. It was very emotional, and my mother came and got me and she was crying. In the next couple of days, James Cleveland was at my house.”

Cleveland visited the Griffins’ East Harlem apartment about a week prior to the Peace Be Still recording. He brought three background singers with him; Gerri recalled the group being composed of two men and one woman, Gloria Griffin (no relation) of the Roberta Martin Singers, who was part of the Cleveland Singers at that time. “My mother cooked dinner for them,” Gerri said. “James Cleveland sat at the piano and taught me the song.”

Earlier that year, in May, the Cleveland Singers made the first recording of James’s new composition, “I Had a Talk with God,” with Billy Preston on organ and John Hason on piano.65 The track was added to the Cleveland Singers’ Savoy LP, The Sun Will Shine after Awhile but, as of mid-September 1963, that album—the last Cleveland worked on prior to Peace Be Still—had yet to be released. Cleveland wanted to try the song again and decided to do so with the Angelic Choir and the Cleveland Singers at the September 19 session.

After Cleveland announces the title of the song and Hason offers a brief introduction on piano, Griffin sings the first line, “I had a talk with God last night,” in B-flat. The youthful energy in her voice, tinged with stomach butterflies, sparks words of tender encouragement from several members of the choir and from Cleveland, who gently whispers, “Sing, Gerri.” Although Griffin builds vocal confidence incrementally, her performance nevertheless possesses a vulnerability absent from the May 1963 Cleveland Singers version. They captured the song in one take that evening. “I just went up to the mike and started singing,” Gerri said.

Shelley finds this song “probably the most harmonically rich of all those on the album.” He notes that the song’s construction—complete with secondary dominants, diminished triads, and other rarely used harmonies— appear in several iterations of one large musical idea that culminates with the choir’s statement of the title lyric.66 “I Had a Talk with God” is the only track on Peace Be Still that prominently features the Cleveland Singers and the choir together. Aside from Cleveland’s, Gerri delivers the album’s longest vocal solo.

The juxtaposition of an eleven-year-old girl singing about having a heart- to-heart chat with God just four days after the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing was not lost on historian Will Boone: “While the news reports and headlines were speaking of a world in which it was terrifying to be a young black girl … the sound of Griffin’s voice declares a counter-narrative…. She sounds empowered by the assurance that ‘He said he’d all my battles fight.’”67

Griffin remembered remaining at the recording session for a little while after her solo, but then she and her parents went home. She does not recall being paid for her solo, nor was compensation on her mind at the time. “It was not like they brought me in at the last minute and I was some big star,” she said. “Nobody knew who I was, and I was only eleven. So I doubt if they paid me anything, because what [Cleveland] did was, he did me a favor…. That’s what it amounted to. He was as big as they came back then, and to have this kind of a break, my mother probably would have paid him!”68

“I Had a Talk with God” became one of the better known tracks on Peace Be Still but not because of radio play. In fact, Gerri doesn’t remember the song ever appearing on local radio, though she adds, “My mother knew [New York radio announcer and promoter] Joe Bostic. She knew all of those people. Knowing her, she probably called into the radio station and told them my daughter is on that album and got them to play it!” Instead, Cleveland’s song became famous when repurposed as “I Had a Talk with My Man,” a soulful love ballad recorded in 1964 by songstress Mitty Collier. Years later, Collier told music historian Robert Pruter that while she was under contract to Chess Records, she and Billy Davis, her manager and producer at the time, were at the Chess studio in Chicago when Davis came upon session musician Leonard Caston listening to Peace Be Still. He was searching for songs to teach his church choir. Hearing “I Had a Talk with God” gave Davis the idea that with a few word changes, the most important of which was replacing God with man, the song could be a great soul ballad for Collier.69

Davis’s intuition was correct. “I Had a Talk with My Man” entered the Cash Box Top 50 R&B singles chart at number thirty-eight in October 1964 and the Top 100 singles chart at number eighty-three. It made the top ten of the R&B singles chart by November of that year.70 Pleased with the response, Davis and Collier followed the single with another secularization of a Cleveland composition. “No Cross, No Crown,” from volume 4 of the James Cleveland and the Angelic Choir’s Sunday Service partnership, became “No Faith, No Love.”71 In 1967 Collier recorded yet another repurposed Cleveland composition, “That’ll Be Good Enough for Me.”

Collier recalls that Cleveland was not pleased to learn that his gospel songs were being rearranged into R&B hits. Moreover, “I Had a Talk with My Man” and “No Faith, No Love” were credited not to Cleveland but to Davis and Caston, with arrangements contributed by Riley Hampton. Collier reminded this writer, however, that Cleveland did the same thing in 1975 to songwriter Jim Weatherly when he transformed his love ballad, “You’re the Best Thing,” an early 1970s hit for both Ray Price and Gladys Knight and the Pips, into a gospel radio favorite with the Charles Fold Singers as “Jesus Is the Best Thing That Ever Happened to Me.”

In retrospect, “I Had a Talk with God” was a gospel song pleading for pop conversion. Its melody and construction were drawn from early 1960s pop balladry, and Gerri’s plaintive solo gave it a girl group sensibility in synch with Chess sides as well as with early Motown ballads. It would be naive to think that Cleveland, as a songwriter, was not inspired, at least in part, by black popular music while writing “I Had a Talk with God.” Ray Charles’s 1956 hit “Hallelujah I Love Her So” inspired Cleveland to write and record “That’s Why I Love Him So” with the Gospel All Stars the following year. Plus, he was becoming an astute businessman whose new publishing partnership with Thurston Frazier undoubtedly benefited from lessons learned the hard way peddling tunes on the cheap to Roberta Martin. If his religious faith and unwillingness to raise the ire of the church community kept him from becoming a full-fledged R&B singer, Cleveland in later years did not shy away from working with popular music icons such as Quincy Jones, Aretha Franklin, Natalie Cole, and Elton John. So if Thomas A. Dorsey gave gospel music its initial bounce and Roberta Martin its light classical ornamentation, James Cleveland injected religious songs with elements of pop balladry. Not that he was the only one: Savoy labelmates Leon Lumpkins and Bishop Charles Watkins knew their way around a pop melody, too, as evidenced by their gospel hits, “Open Our Eyes” and “Heartaches,” respectively. So did Reverend Lawrence Roberts, with his appropriation of Charles’s “Hit the Road Jack” for “It’s the Holy Ghost” on the Angelic Choir’s first album.

And as for Gerri Griffin, her wish for a career in musical performance ultimately came true, but not from “I Had a Talk with God”—with the exception of a complimentary article in the New York Amsterdam News, she wasn’t cited as the soloist anywhere. She did share the stage with the Roberta Martin Singers, but more important, she leveraged her mother and Bernice Cole’s advocacy, as well as her own talent and gumption, to secure a spot in the cast of the musical Hair and, more visibly, as lead singer for the Voices of East Harlem, a youth choir her parents organized out of her father’s East Harlem Youth Federation. With the passion of a gospel choir, the unfettered choreography of street dancing, and declarations of universal brotherhood, the Voices of East Harlem recorded three critically acclaimed albums. They shared the stage with some of the era’s most influential soul, folk, and rock acts, from Ike and Tina Turner to the Who. They toured Europe and appeared at the Isle of Wight Festival. They even traveled to Accra, Ghana, to be part of the Soul to Soul music festival (a documentary film and album of the event are available).

Looking back, Gerri Griffin Watlington, who now dedicates her work to the church, remembers her participation on Peace Be Still as “almost a fluke. Had Bernice not found out [Cleveland] was going to be in New York, had she not arranged that, I would never have been on it.”72

“Where He Leads Me”

At this point, Cleveland and the Angelic Choir shift from a newly composed song to a standard hymn, “Where He Leads Me.” In 1890 a Salvation Army officer named Ernest William Blandy wrote the lyrics to “Where He Leads Me” to express how the Lord led him to forgo a comfortable position at an established church for a more challenging ministry in New York City’s infamous Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood. The opening line, “Where He leads me, I must follow,” is Blandy’s Christian pledge of fidelity to Jesus and his teachings. Supplying the melody was John Samuel Norris, a Methodist born on the Isle of Wight who became a Congregationalist minister and served churches in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Iowa before he passed away in Chicago in 1907.73

By 1963 “Where He Leads Me” was a popular selection in African American Protestant hymnbooks. It appeared as number forty-six in the National Baptist Convention’s Gospel Pearls, a staple for gospel singers since its publication by the Convention’s Publishing Board in 1921. An arrangement by Philip P. Bliss, who with Ira Sankey in 1874 coauthored the first hymnbook to use the phrase “gospel song” in its title, was included in Gospel Quintet Songs, a 1920s folio associated with the Christian and Missionary Alliance Colored Gospel Quintet (also known as the Cleveland [Ohio] Colored Quartet). The song was recorded around February 1929 by country blues guitarist Blind Willie Harris, who cut a version in New Orleans for Vocalion. In April of that year, the Southern Sanctified Singers recorded the hymn in Chicago for Brunswick Records.74 In the early 1950s, tenor Thomas Johnson led the Harmonizing Four of Richmond, Virginia, on a smooth and imperceptibly rhythmic reading of the hymn for Gotham Records. Around the same time, Ray Crume led Chicago’s Highway QCs gospel quartet on a more soulful version for Vee Jay Records. In 1961 Mahalia Jackson rendered the song with great solemnity on one of the eighty-four five-minute television segments packaged and distributed nationally as Mahalia Jackson Sings.75

The song also became popular among southern gospel groups, with recordings that included a 1941 release by the influential Rangers Quartet on Conqueror, appearance on a 1966 Starday album by the Lewis Family, and a version by the Blue Ridge Quartet in 1970.76 Country music icon Hank Williams performed it on a 1951 WSM radio broadcast, with his Drifting Cowboys band members providing vocal harmony like a southern gospel quartet. A sixty-year-old Jimmy Davis, two-term governor of Louisiana and composer of “You Are My Sunshine,” included the hymn on his 1959 Decca album, Suppertime.77

For Peace Be Still, Cleveland sets “Where He Leads Me” in D-flat and, structurally, as a call and response between him, the choir, and the live recording audience and congregation. He opens with the declaration “I told God one day these words,” and then launches into a meter-less falsetto reading of the hymn’s refrain as Herriot improvises on the organ in support. While the following verse, “I’ll go with Him through the valley,” is not one of Blandy’s originals, it does fit with Blandy’s second and third verses, “I’ll go with Him thro’ the garden” and “I’ll go with Him thro’ the judgement,” respectively. Then, placing Blandy’s intentions in his own words, Cleveland retorts, “If it means I’ll have to cry sometimes / If it means I’ll have to fold my arms sometimes / “I’ll be with Him all the way.” The choir echoes Cleveland’s “with Him all the way” in a whispered harmony as the first side of the album draws to a close as solemnly as it opened.

“This song stands apart from all the rest [on the album],” notes Shelley, “because of the light, falsetto-like phonation that Cleveland employs throughout the song.”78 And it is the first time, though not the last, on Peace Be Still that Cleveland will raise a traditional church hymn for the purpose of leading congregational singing, another effort to recreate the authentic African American worship experience for the phonograph-record-listening public, and perhaps encourage listeners to sing along.

But although “Where He Leads Me” restates the themes of discipleship and faith as articulated on “Peace Be Still” and “Jesus Saves,” it also reminds listeners that the call might be unclear initially and provoke personal resistance. Like Blandy’s reaction to the call to minister in an undesirable location and, like Cleveland’s initial resistance to live recording, walking in faith produces rewards.

“God Is Enough”

After “Where He Leads Me,” the choir recorded “God Is Enough,” but for some reason it was neither included on Peace Be Still nor released commercially until Cleveland and the Angelic Choir attempted it again for the next Sunday Service volume, 1964’s I Stood on the Banks of Jordan. The 1964 version is a duet between Cleveland and an effervescent soprano from the Angelic Choir, possibly Marjorie Raines (at one point during the soprano’s final solo turn, a fellow chorister shouts “Sing, Margie!”), with the choir punctuating the duet with bursts of dense harmony.

Sustaining the slow, even tempo of “Where He Leads Me,” Cleveland introduces a theme he would expound on again in “Heaven, That Will Be Good Enough for Me,” his 1965 hit with the Cleveland Singers. In stark contrast to prosperity theology, which assures financial blessings to faithful Christians, James sings in “God Is Enough” that material possessions pale in comparison to the grace of God and the reward of eternal life. On “Heaven,” Cleveland sings, “I’ve never been to Paris in the spring or the fall / I’ve never been to India to see the Taj Mahal / But if I can make it to Heaven, that will be good enough for me / Because Heaven is a place I want to be.” Similarly, on “God Is Enough,” he offers “Rubies and diamonds I don’t possess / But I’ve got Jesus and, with Him, I’m blessed.” The line also conjures the hook of “That’s Enough,” a 1956 hit for the Gospel Harmonettes, led by its composer, Dorothy Love Coates (“I’ve got Jesus, and that’s enough”). In any event, this testimony to the limitless power of God is articulated through a sung conversation between Cleveland, Raines, and the Angelic Choir. It calls to mind an opera or Broadway musical recitative.

Unissued on Peace Be Still, “God Is Enough” must have pleased Cleveland, Roberts, and the Savoy team the second time around, as it became the flip side of “No Cross, No Crown” (Savoy 4318), one of I Stood on the Banks of Jordan’s two single releases. Oddly, as far as is known, the song was never recorded again after 1964—by Cleveland, by the Angelic Choir, or by any other African American gospel artist.

“My All and All”

The other unissued selection from the September 19, 1963, session is “My All and All.” Cleveland and the choir attempted it again during the 1964 I Stood on the Banks of Jordan session, but it did not make the final cut on this volume either. In fact, James Cleveland and the Angelic Choir never recorded “My All and All” together. It does not show up on an Angelic Choir record until 1967, when the troupe featured it on their own album, The Soul and Faith of the Angelic Choir. It’s there we discover that the song is a gospelization of Marvin Gaye’s April 1963 single, “Pride and Joy.”79 Instead of “You are my pride and joy,” the choir sings “You are my all and all.”

With Freeman Johnson handling the lead vocal, the song’s gospel-meets- Motown vibe was augmented by the accompaniment of electric guitar, tambourine, bass, and drums. Like 1961’s “It’s the Holy Ghost,” “My All and All” was an example of Roberts converting popular R&B songs into church arrangements. Notwithstanding its radio potential, “My All and All” was never released as a single and, as of this writing, the two unissued Peace Be Still matrices remain undiscovered.80

“I’ll Wear a Crown”

Although attributed to James Cleveland, only the arrangement of “I’ll Wear a Crown” belongs to him. The song, also known as “I Shall Wear a Crown,” is a spiritual and therefore precedes modern gospel music. It was recorded in Chicago on July 3, 1928, by Church of God in Christ pianist Arizona Dranes.81 It was her final recording session for OKeh Records and, as it turned out, in her lifetime. In 1950 Dave Dexter, artists and repertoire director of Capitol Records’ R&B line, paired the Reverend R. A. Daniels, a blind preacher from Portland, Oregon, with the Mount Zion Church Gospel Choir of Santa Monica, California. Their energetic, tambourine-soaked version, cut as a Capitol single, was likely an intentional decision on Dexter’s part to capitalize on the popularity of St. Paul Baptist’s Echoes of Eden, also on Capitol.82 Eight years later, the Stars of Faith, with Henrietta Waddy on lead vocal, recorded an equally energetic version of the song for Savoy.83

Notwithstanding Cleveland’s arrangement credit, “I’ll Wear a Crown” on Peace Be Still sounds like another example of Lawrence Roberts’s playful blend of religious lyrics with elements of R&B and rock ’n’ roll. Set in B-flat, the arrangement employs the stimulating “twist” dance rhythm that had been popular since the 1959 release of “The Twist” by Hank Ballard and the Midnighters and Chubby Checker’s mainstream 1960 cover.84 The rhythm section of organ, piano, and drums is helped by the choir’s hand clapping. Perhaps more than any other song on the album, “I’ll Wear a Crown” benefits from Joe Marshall’s rock ’n’ roll experience, the thudding of his toms ricocheting off the walls and ceiling of Trinity Temple. Shelley also hears the song’s heavy syncopation, its lyrics cutting against the grain of the 4/4 meter.85

The lively twist beat is an effective complement to lyrics about facing down death with optimism instead of despair. Cleveland opens with a spoken evocation of the hereafter: “Those of us that have sent up our timber, we have laid up a crown of life, and we shall wear a golden crown.” Every line he utters receives assent from a sole female voice (possibly Gertrude Hicks). To reinforce the image of entering heaven, Cleveland and the Angelic Choir pull lines liberally from spirituals and from the Reverend W. Herbert Brewster’s “Move On Up a Little Higher,” Mahalia Jackson’s breakout hit of 1948. The Angelic Choir quotes “Move On Up a Little Higher” in the chorus: “Soon as my feet strike Zion / Lay down my heavy burden / Put on my robe in glory / Shout and tell my story.” Cleveland then improvises on Brewster’s composition, adding “see my mother / shake hands with my brother,” then transitions into the folk spiritual “All God’s Children Got Shoes.” He disappears off mike, momentarily overcome by the spirit, though he can be heard shouting phrases imperceptibly in the distance. His return to the microphone signals the song’s conclusion.

Shelley hears “a kind of narrative teleology that drives the song forward” in how the two main sections of the song treat the title lyric in opposite ways. “The A section opens with ‘Watch ye therefore’ and ends with ‘We shall wear a golden crown,’ while B opens with ‘I shall wear a crown’ and ends with ‘I shall wear a crown.’” He also notes the song’s “bluesy emphasis on the subdominant IV, which stands in contrast to ‘The Lord Brought Us Out’ [the selection that follows “Crown”]. Halfway through the chorus, you can hear/feel the move to IV, in this case an E-flat chord, at ‘oh, I shall wear a crown.’”86

The song remains a popular selection in the gospel music repertory. Soloist Gene Martin recorded it during an A. A. Allen revival service at New York’s Rockland Palace. Like Savoy’s Sunday Service series, Allen’s disks were live in-service recordings of revival-like events that featured spirited interaction with the recording audience and congregation.87 Whether or not he was invoking the Cleveland–Angelic Choir version, Martin also interpolates the spiritual “All God’s Children Got Shoes” several times during his version of “Crown” as David Davis and Tommy Downing accompany him on organ and piano, respectively. Detroit choir director, songwriter, and arranger Thomas Whitfield presented “I Shall Wear a Crown” under the title “Soon as I Get Home” in a 1983 live recording with his Thomas Whitfield Company. Although the aforementioned versions of the song were performed to a vigorous beat, Whitfield characteristically offers a slow and sumptuous reading with jazz and classical flourishes.88 Whitfield’s arrangement was the version sung by a choir at the August 31, 2018, funeral of Aretha Franklin—an appropriate choice, since Detroiters Franklin and Whitfield were both profoundly influenced by Cleveland. “Crown” was also among the traditional gospel classics rendered by a chorus of renowned gospel singers at the appropriately titled Gospel Pioneers Reunion, recorded in 1994 by southern gospel maven Bill Gaither and released commercially as a DVD and CD in 2016.

Like “Peace Be Still,” “I’ll Wear a Crown” exemplifies what religious music scholar Jon Michael Spencer calls a distinguishing factor of Cleveland’s lyric content and, ultimately, his personal theology. Citing Louis-Charles Harvey’s mid-1980s article “Black Gospel and Black Theology,” Spencer writes that, for Cleveland, “Jesus is the answer to the problems in black life.” But there is a price to pay. Although Jesus serves as “friend, protector, and liberator,” there is a certain “cross-bearing” that Christians must experience to gain entrance to eternal happiness.89 The metaphor for “weather[ing] the storms and rains of life” is cross-bearing; that is, there is no gain without pain. No cross, no crown. As a common church aphorism goes, one must go through to get to. Cleveland’s personal theology is sprinkled liberally throughout Peace Be Still.

“The Lord Brought Us Out”

The fastest-paced selection on Peace Be Still is “The Lord Brought Us Out,” a song in 4/4 time written by Cleveland and not recorded commercially prior to its inclusion on this session. After Cleveland’s spoken introduction— “We can brag tonight because the God we serve is able”—the musicians lurch into a steadily rolling march tempo. The song’s sole musical motive is repeated antiphonally between Cleveland and the choir. Behind them, the piano and organ play a simple, repetitive bass ostinato of B-flat-F-G-A as the choir augments the rhythm with fervent handclapping and percussive tambourine shaking.

Shelley adds, “Tonally speaking, ‘The Lord Brought Us Out’ is in B-flat major with some modal mixture, especially on the ‘Oh yes,’ which culminates on a D-flat major chord, a borrowed chord from the parallel minor. The relative stasis of its harmonic character, the fact that the first three statements of the title lyric occur on an uninterrupted tonic (I) chord, really stands out in comparison to songs like ‘I’ll Wear a Crown,’ where the movement to the subdominant (IV) has expressive weight.”90

Lyrically, Cleveland turns once again to the subject of divine rescue introduced on “Peace Be Still.” Here, he cites three biblical stories instead of one: Daniel in the lion’s den (Daniel 6:1–28); the rescue of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego from the fiery furnace (Daniel 3:16–28), and Jesus meeting the Samarian woman at the well (John 4:1–26). The assumption is that if God saved these individuals—Daniel from carnal destruction, the Hebrew boys from incineration, and the Samarian woman from spiritual corruption, He will save everyone. Cleveland reiterates the cross-bearing theme of “I’ll Wear a Crown.” Weathering the storms of life is the way to gain entrance to heaven. In jubilant antiphony, Cleveland declares, “The Lord God almighty done” and the Angelic Choir responds with “brought us out.” They repeat this phrase together three times and conclude with a soaring, confident, and extended “Oh yes,” the B-flat-F-G-A ostinato fueling the motive power of the choir’s sustained notes.

Perhaps because it is more of a spontaneous congregational chant than a through-composed song, “The Lord Brought Us Out” was not reprised on future albums by Cleveland or the Angelic Choir.

“Shine on Me”

Cleveland and the Angelic Choir return to classic hymnody with a B-flat rendition of “Shine on Me.” The melody comes from “Maitland,” a nineteenth- century composition by George N. Allen (1812–77). The hymn’s chorus, based loosely on Psalm 31:16 (“Make thy face to shine upon thy servant: save me for thy mercies’ sake”) has its origins in a folk spiritual. It was recorded by African American artists as early as 1923, when the Wiseman Sextette sang it for Billy Sunday music director Homer Rodeheaver’s Rainbow Records; in 1927 by the professional jubilee choir Sandhill’s Sixteen (Victor); and in 1929 by Blind Willie Johnson as “Let Your Light Shine on Me” (Columbia).91 Country gospel singers Ernest Phipps and His Holiness Singers also recorded the hymn for Victor in 1928. In the introduction to his recorded version, blues guitarist Huddie William “Leadbelly” Ledbetter (1888–1949) explained that “Shine on Me” was sung on plantations by African Americans prior to emancipation.

Cleveland opens “Shine on Me” with his now almost obligatory spoken introduction. “Sometimes our ways get mighty dark,” he intones in his sandpaper-rough baritone, “and we need the Lord to come into our heart.” Unconsciously echoing Leadbelly, Cleveland informs the choir and live audience that “Shine on Me” was sung in the “little wooden church on the hill” as a long-meter hymn. To render a long-meter, or lining-out, hymn in the African American church, a church deacon lifts, or raises, a lyric line and invites the congregation to sing it back to him in a heavily ornamented melody. While this recorded version maintains the drawn-out tempo, it is not sung as a long-meter hymn; there is no antiphonal interplay with the Angelic Choir or congregation. Rather, it is sung as a congregational hymn and in harmony. As a result, “Shine on Me” is a showcase for the vocal power of the Angelic Choir (fortified, undoubtedly, by singing from the congregation) and for Cleveland’s improvisational skills, which portend his calling to religious ministry. Hason and Herriot follow Cleveland and the choir with Roberta Martin-esque ornamentation from the middle section of the keyboard.

Shelley finds Hason’s keyboard work particularly interesting: “The rumbling chords in the left hand of the piano fill the space while the choir and soloists are breathing. It’s like a performance of freedom, and a performance of pregnant pauses.”92

It is interesting that, when Cleveland declares, “Sometimes our ways get mighty dark,” not only does he restate the cross-bearing current that runs throughout the album, but it is possible he is making a veiled reference to discrimination and racially motivated violence. The metaphor of a lighthouse lighting the way toward salvation certainly fits on an album brimming with imagery of raging storms and wind-tossed seas. And by invoking pastoral “little wooden church” imagery, Cleveland is reminding the congregation and choir not only of their shared southern religious roots but of the transformational power of traditional worship. The singers, the live recording audience, and, in turn, the record-buying public can leave their troubles on the altar and breathe in a deep, satisfying gulp of old-time religion—the type that sustained their forebears. Cleveland is also unconsciously channeling early-twentieth-century US immigrant entertainers who sang songs that evoked nostalgia for a simpler time in the pastoral Old World—more paradigmatic than realistic—as a way to cope with the often-alienating New World.93 For Cleveland, the “wooden church” down south represents an oasis of safety and predictability in a world that is anything but, even if that southern experience was sufficiently demeaning, debilitating, and dangerous to effect mass migration. This juxtaposition of old hymns sung in a modern setting is yet another thematic element running through the entirety of Peace Be Still.

“I’ll Be Caught Up to Meet Him”

References to the Reverend W. Herbert Brewster’s “Move On Up a Little Higher,” having already adorned “I’ll Wear a Crown,” remain firmly fixed in Cleveland’s consciousness as he opens the equally apocalyptic “I’ll Be Caught Up to Meet Him.” In a half-spoken, half-sung one-minute opening narrative, Cleveland describes heaven, in Brewster’s words, as a joyous place “where there will be no more crying, no more sorrow” and “always howdy, howdy, and never goodbye.” In other words, the storms of life have been calmed and the Christian, if faithful, can anticipate eternal happiness.

“I’ll Be Caught Up to Meet Him” is based loosely on the concept of the Rapture as referenced in 1 Thessalonians 4:16–18, and particularly this line: “Then we which are alive and remain shall be caught up together with them in the clouds, to meet the Lord in the air: and so shall we ever be with the Lord.” The words and music were composed around 1944 by Clarence E. Hatcher under the full title “I’ll Be Caught Up to Meet Him in the Air.” Around the time he composed “Caught Up to Meet Him,” Hatcher, born in Brooklyn, New York, was a member of Brown’s Inspirational Singers, organized by Beatrice Brown. Members of the Indianapolis, Indiana, gospel troupe, which sang in the measured elegance of the Roberta Martin Singers, included gospel pianist-arranger Kenneth Woods Jr. and Meditation Singers and television star Della Reese.94 Heralded as “America’s greatest gospel pianist” in the mid-1940s, Hatcher founded a publishing company in Brooklyn and wrote other gospel music favorites. Handling the arrangement was Virginia Davis, a Chicago-based musician who wrote and arranged hundreds of gospel songs during gospel’s golden era.95 Davis’s “Wonderful,” a dreamy pop-gospel ballad recorded in 1956 by the Soul Stirrers, was restyled by the Stirrers’ erstwhile lead vocalist, Sam Cooke, as “Lovable.” It was Cooke’s first secular single.

Probably because of its Brooklyn provenance, “I’ll Be Caught Up to Meet Him” bounced around the East Coast gospel music scene before Cleveland and the Angelic Choir picked it up. Sometime in the 1940s, the influential Mary Johnson Davis Singers of Philadelphia were captured on acetate singing the song, and the Banks Brothers’ Back Home Choir of Newark included it on their 1958 RCA Victor album, I Do Believe.96 The Back Home Choir’s version was zestier than the heavy-handed waltz employed by Cleveland and the Angelic Choir. Also, the Back Home Choir recorded “I’ll Be Caught Up to Meet Him” as an ensemble, whereas Cleveland assumes lead vocal duties for the Peace Be Still album. He also reverses the placing of the chorus and verse as rendered by the Back Home Choir.97 Around the same time as Peace Be Still, the Metropolitan Baptist Church of New York City’s Prayer Meeting Chorus recorded the Back Home Choir’s version for its own in-service album.98

The only song on Peace Be Still set in A-flat and with a moderate 6/8 tempo, “Caught” features what Shelley calls a fascinating “double call-and-response,”99 as Cleveland personalizes a moving couplet popular in 1950s and 1960s gospel: “One of these mornings / It won’t be long / You’ll look for James / And he’ll be gone.” During the vamp, Cleveland embarks on a metaphorical search for his sister and his brother who have passed through the pearly gates (in reality, his siblings were very much alive at the time).

Like other selections on Peace Be Still, “Caught Up to Meet Him” has remained a church choir staple. It has been recorded live by the Combined Choirs of the Fourth Missionary Baptist Church of Houston, Texas (1969), by Dr. Jonathan Greer and the Showers of Blessings Choir of the Cathedral of Faith Church of God in Christ (1980), by the West Angeles Church of God in Christ Mass Choir (1990), and Professor Ronnie Felder and the Voices of Inspiration of Brooklyn, New York (2002). To this writer, the Angelic Choir’s enthusiastic evocation of Heaven, and Cleveland’s vocal runs from deep growl to falsetto, are compelling, but the Back Home Choir’s recorded version, with its bouncy tempo, is far more engaging.

“Praise God”

Of all the live recordings of African American worship services prior to Peace Be Still, none contained the best-known and most beloved hymn of doxology in African American Protestant worship: “Praise God from Whom All Blessings Flow:”

Praise God, from whom all blessings flow;

Praise Him, all creatures here below;

Praise Him above, ye heavenly host;

Praise Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. Amen.

With lyrics written in 1674 by Anglican Bishop Thomas Ken (1637–1711), one of the fathers of modern hymnology, “Praise God” has the oldest provenance of any selection on the album. Ken wrote the four lines for two separate hymns, “Awake, My Soul, and with the Sun” and “Glory to Thee, My God, This Night,” to be sung at morning and evening worship at Winchester College in Hampshire, England, where he served at the time he composed these two hymns.100

Though “Praise God” was a product of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—it was published in 1709—its melody is attributed to sixteenth- century French composer Louis Bourgeois (ca. 1510–59). Bourgeois was supervising composer for the 1551 edition of the Genevan Psalter, a book of metrical hymns commissioned by John Calvin, the French theologian whose beliefs helped form the Calvinist tradition. The tune was commonly known as “Old Hundredth” because of its initial use as the melodic setting of Psalm 100, the “Song of Thanksgiving.” As a unified composition, “Praise God” made its way into the hymnbooks of African American Protestant churches as they expanded in number after Reconstruction. It is often used for a service’s doxology, meaning an expression of praise to God that concludes the formal service. Perhaps the close association of “Praise God” with the formal order of worship service and not commercial gospel singing explains why it was not recorded by any gospel artist prior to Peace Be Still, though a few choirs did incorporate it into their live recordings after 1963.101

With all the austerity of a senior choir, the Angelic Choir chants the “Old Hundredth” in D-flat major as Reverend Roberts, as presiding pastor, recites the lines. But his recitation is about as close as “Praise God” comes to gospel music. Its inclusion on the album as a text made the program feel like a traditional worship service, not a gospel music album, with the congregation invited to join in the singing prior to dismissal.

Although the choir sounds fatigued from a long evening, it reenergizes during the rococo “Amen.” To Shelley, the sevenfold amen makes the selection “a kind of double doxology.”102 Then, after singing the first syllable of the final “Amen,” the choir pauses for nearly four seconds, waiting for Roberts to direct them to sing the final syllable on the tonic chord. As they conclude, Roberts’s softly spoken “Amen” overlays the choir’s singing of the second syllable (-men) as the cymbals hiss and the recording ends. In addition to being the oldest song on Peace Be Still, “Praise God” is also the shortest of the album’s nine selections, clocking in at just two minutes and eleven seconds.

The air was heavy with solemnity at the conclusion of the September 19 recording session, the time nearing, or perhaps past, the midnight hour. The storm had been quieted, the choir had rendered profuse praises to God for not only rescuing them from certain destruction but for also offering them eternal life in exchange for their Christian fidelity. The peaceful stillness in Trinity Temple was palpable as Paul Cady switched off the recording mechanism. As he boxed the tapes and marked the boxes, as Marshall disassembled his drums, and as Herriot shut down the organ, the choir and congregants broke the silence with pleasant chatter and bursts of discreet laughter. They relived the night’s highlights and lowlights with one another as they gathered their belongings and headed toward the church exits to meet the serene night sky and face another Friday workday, just a few hours away.