The Cross-Border Challenge in Resolving Global Systemically Important Banks

Jacopo Carmassi and Richard Herring

Introduction

Just before the global 2008 financial crisis, the issue of large, complex financial institutions (LCFIs) began to catch the attention of some policymakers.1 In general, however, officials appeared not to have anticipated the problems that would need to be addressed if one of these institutions should need to be resolved, much less considered whether the complex corporate structures of such institutions would impede or even prevent an orderly resolution.

The orderly resolution of even a purely domestic, complex financial institution presents formidable difficulties no matter whether an administrative or bankruptcy process is deployed. But the difficulties increase by an order of magnitude if the complex financial institution is international in scope. While excessive risk-taking and leverage may have caused the crisis, institutional complexity, often involving tiers of foreign affiliates, and opaque, cross-border interconnections impede effective oversight by the authorities ex ante and greatly complicate crisis management and the resolution of institutions ex post.

The second section of this chapter outlines the scope of the problem. Section three reviews some data depicting the organizational complexity and the international legal structure of the twenty-nine institutions that have been designated as global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) in November 2013. The fourth section discusses the implications of complexity for orderly resolution. The fifth section examines why any orderly procedure for a cross-border resolution must rely on a significant amount of cooperation among national authorities and considers why governments have great difficulty in making credible commitments to cooperate with foreign authorities and abstain from ring-fencing the portions of a foreign financial group that they control. A failure to find a way to ensure cooperation in a crisis may lead to extensive subsidiarization and a substantial amount of fragmentation in the global financial system. The sixth section explores the implications of this approach. And, the concluding section emphasizes the problems resulting from the lack of a plausible framework for the cross-border resolution of G-SIBs.

The Scope of the Problem

The financial crisis of 2008–2009 highlighted the complex, opaque, cross-border structures and interconnections among G-SIBs. As Mervyn King (2010) observed, these entities are global in life, but local in death.2 Each of the legal entities within the group must be taken through some sort of resolution no matter whether it be bankruptcy, an administrative resolution, or, in the case of a prepackaged bankruptcy, the unwinding of contracts. During the crisis, the challenges of coordinating, much less harmonizing, scores of legal proceedings across multiple jurisdictions proved to be insuperable, particularly within the tight time constraint of a “resolution weekend” (Huertas 2014). Once the financial group has been dissolved into separate legal entities, information can become so fragmented that it is virtually impossible to preserve any going-concern value the group may have had. Indeed, in the case of Lehman Brothers, it proved difficult even to gather the data necessary to resolve many of the separate entities.3

When policymakers were confronted with the magnitude of the challenge of devising an orderly resolution for a large, complex, global financial institution, they appear to have believed they had no good choices. A bailout would avoid the anticipated short-term costs of a disorderly resolution which might inflict significant harm on other financial institutions, financial markets, and, most importantly, the real economy. But a bailout could impose huge fiscal costs and might increase the likelihood that even larger and more costly bailouts would be necessary in the future. Nonetheless, when faced with the choice between immediate and possibly uncontrollable damage to the economy and possible future harm and fiscal costs that could be delayed, the authorities frequently chose to organize a bailout.

The magnitude of the bailouts implemented during the recent crisis was so great4 that they could not be convincingly justified on political or economic grounds. Leaders of the Group of Twenty, meeting in the depth of the crisis, reached a consensus neatly summarized by Huertas (2010) as “too big to fail5 is too costly to continue.” The rallying cry was that taxpayers should never again be put at risk of such substantial losses, but the authorities realized that they lacked effective tools to deal with a faltering G-SIB. This realization has led to a number of policy innovations, many of them still in the process of implementation.

The Extent of Organizational and Geographic Complexity among G-SIBs

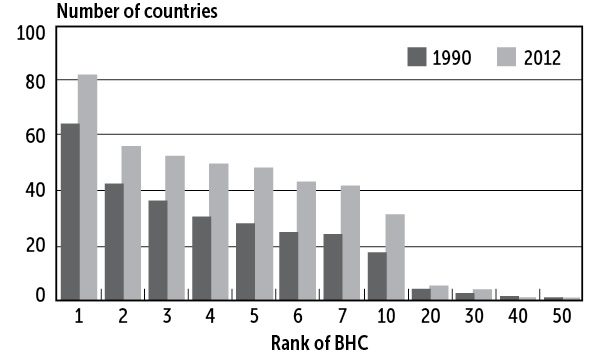

Several of the G-SIBs have developed remarkably complex corporate structures and a vast global reach. These trends can be documented for the largest bank holding companies in the United States. Figure 9.1a shows the number of subsidiaries controlled by the largest US bank holding companies. Six bank holding companies now control well over one thousand subsidiaries. Relative to 1990, corporate complexity for several of these bank holding companies had increased markedly. Figure 9.1b depicts the international expansion of these firms. Seven of them are now active in more than forty countries and one is active in more than eighty countries.

Figure 9.2 shifts the focus to the G-SIBs identified by the FSB (which include eight US bank holding companies). This chart shows the evolution of the average number of subsidiaries and total assets for the twenty-nine G-SIBs from 2002 through 2013. Note that despite all of the regulatory and supervisory measures adopted to encourage banks to simplify their corporate structures since the crisis, the average number of subsidiaries continued to grow after the crisis, peaking in 2011. The average number of subsidiaries has begun to decrease a bit, but has still not returned to pre-crisis levels, when many of these firms were implicitly deemed too complex to fail.

Figure 9.1a. Number of Subsidiaries of the Largest US Bank Holding Companies

Source: D. Avraham, P. Selvaggi, and J. I. Vickery, “A Structural View of U.S. Bank Holding Companies,” Economic Policy Review 18, no. 2 (July 16, 2012), on National Information Center data and FR Y-10. Data as of February 20, 2012, and December 31, 1990.

Figure 9.1b. Number of Countries in Which US Bank Holding Companies Have Subsidiaries

Source: D. Avraham, P. Selvaggi, and J. I. Vickery, “A Structural View of U.S. Bank Holding Companies,” Economic Policy Review 18, no. 2 (July 16, 2012), on National Information Center data and FR Y-10. Data as of February 20, 2012, and December 31, 1990.

Figure 9.2. Evolution of Average Number of Subsidiaries and Total Assets for G-SIBs

Source: Based on Bankscope data.

Note: Majority-owned subsidiaries for which G-SIBs are the ultimate owners with a minimum control path of 50.01% at all steps of the control chain.

Figure 9.2 also shows the growth in average total assets for these firms. Average total assets increased by more than 2.6 times from 2002 to 2008. This fell a bit during 2009 and 2010, when several of these firms were obliged to deleverage, but by 2011 average total assets had once again risen to their pre-crisis highs and remained very close to that level through 2013. The data on total assets and the total number of subsidiaries reveal a fairly robust correlation.6 This probably reflects the influence of the mergers and acquisitions through which most of the G-SIBs grew. Although most made efforts to reduce the resulting legal complexity, the number of subsidiaries tended to ratchet up significantly.

Table 9.1 provides additional details about the universe of the G-SIBs in 2013. The largest bank in the group had more than $3 trillion in assets, while the average across G-SIBs was $1.6 trillion in assets. International involvement as measured by the percentage of foreign assets is remarkable. For the most international bank in this group, 87 percent of its assets were foreign, while for the average of G-SIBs it was 42 percent. Complexity, as measured by the total number of subsidiaries in the banking group, ranges from a high of 2,4607 to an average of 1,002. On average, 60 percent of these subsidiaries are incorporated in countries other than the home country; for one of the G-SIBs, 95 percent of its subsidiaries are incorporated abroad. A rough (and very minimal) indication of the role that tax incentives play in this corporate complexity can be inferred from the proportion of subsidiaries incorporated in offshore tax havens. On average, 12 percent of the subsidiaries are incorporated in such offshore banking centers, while one G-SIB incorporated 28 percent of its subsidiaries in tax havens.

On average, G-SIBs are active in forty-four countries, while one G-SIB has a presence in ninety-five countries. This is a minimal estimate of the coordination challenge that must be met over a resolution weekend if the authorities hoped to continue most of the operations of the G-SIB on Monday morning. This should be regarded as a lower bound for two important reasons. First, the count ignores foreign branches. Although a domestic branch is an integral part of the head office and would be subject to whatever resolution procedure is applied to the parent, the outcome may be different if the branch is located overseas. Foreign branches may be subject to ring-fencing by the host country in the event of a crisis and thus subject to a separate resolution process. Second, this count almost certainly understates the coordination challenge because several countries may have two or more specialized regulators that would need to be consulted to resolve or continue operation of an individual entity. A foreign bank operating in the United States, for example, would be required to have separately regulated subsidiaries for insurance activities (one for each state in which it operates), the broker-dealer business, commodity trading, and deposit-taking.

Table 9.2 provides an indication of the complexity that may arise because of the diverse activities conducted by a G-SIB by disaggregating the total number of subsidiaries by category of business. The banking business accounts for only 4 percent of the subsidiaries, although these subsidiaries account for the majority of assets. Only 1 percent of the total number are insurance companies. Other financial subsidiaries—including, among others, mutual funds, pension funds, hedge funds, and private equity funds—account for another 47 percent of the total number of subsidiaries. More surprising, however, is that the remaining 47 percent of subsidiaries fall into the heterogeneous category of “non-financial subsidiaries,” which includes manufacturing activities, trading of non-financial products, foundations, and research institutes.

Many, perhaps most, of these entities would not pose an obstacle to an orderly resolution because they may be automatically liquidated when some specified threshold condition is crossed or they may be totally insulated from the rest of the group.8 Given current disclosure practices, however, an external observer lacks sufficient information to evaluate what kind of activity takes place in such an entity, its scale, and its interrelationships with the rest of the group or the resolution procedure it would need to undergo in the event of failure (Carmassi and Herring 2013).

In any event, the more numerous the legal entities, the greater the likely number of regulatory entities that must be consulted in planning and implementing a resolution. Because G-SIBs conduct a wide variety of businesses beyond banking and securities activities, this may involve a broad range of specialized, functional regulatory authorities, including insurance commissioners and, in the case of energy trading units, possibly even very specialized regulators such as the Environmental Protection Agency.9 Assuming that all of these parties have the legal ability and willingness to cooperate—and that their rules and procedures do not conflict—coordination costs will be high and will increase with the number of regulatory authorities that need to be consulted. Of equal importance, the greater the number of regulatory authorities that need to be consulted to start an orderly resolution process, the greater the likely number needing to be convinced to provide licenses and permissions in order for the bridge institution to continue critical operations on the Monday following the resolution weekend. Moreover, these operating entities must receive authorization to continue using critical elements of the financial infrastructure (such as payments systems, clearing, and custody services) and to continue trading on exchanges.

Problems That Geographic and Business Complexity Pose for an Orderly Resolution

Despite their corporate complexity, G-SIBs tend to be managed in an integrated fashion along lines of business with only minimal regard for legal entities, national borders, or functional regulatory authorities. Moreover, interconnections among entities within the group are opaque and may be quite substantial. Baxter and Sommer (2005) note that, in addition to their shared (although possibly varying) ownership structure, the entities are likely to be linked by cross-affiliate credit, business, and reputational relationships.

What would happen should one of these G-SIBs experience extreme financial distress? Quite apart from the difficulty of disentangling operating subsidiaries that provide critical services and mapping an integrated firm’s activities into the entities that would need to be taken through a bankruptcy process, the corporate complexity of such institutions would present significant challenges. The fundamental problem stems from conflicting approaches to bankruptcy and resolution across regulators, across countries, and, sometimes, even within countries. There are likely to be disputes over which law and which set of bankruptcy or administrative procedures should apply. Some authorities may attempt to ring-fence the parts of the G-SIB within their reach to satisfy their regulatory objectives without necessarily taking into account some broader objective such as the preservation of going-concern value or financial stability. At a minimum, authorities will face formidable challenges in coordination and information-sharing across jurisdictions. Losses that spill across national borders will intensify conflicts between home and host authorities and make it difficult to achieve a cooperative resolution of an insolvent financial group. Experience has shown that in times of stress information-sharing agreements are likely to fray (Herring 2007).

When the crisis erupted, approaches to bank resolution differed substantially across countries. For example, countries differ with regard to the point at which a weak bank requires resolution and with regard to which entity initiates the resolution process. Clearly cross-border differences in regard to how and when the resolution process is initiated can cause conflicts and delays that may be costly in a crisis.

The choice of jurisdiction may also have important implications for the outcome of the insolvency proceedings. Most countries have adopted a universal approach to insolvency in which one jurisdiction conducts the main insolvency proceedings and makes the distribution of assets, while other jurisdictions collect assets to be distributed in the main proceedings. But the United States follows a more territorial approach with regard to US branches of foreign banks and will conduct its own insolvency proceedings based on local assets and liabilities. Assets are transferred to the home country only after (and if) all local claims are satisfied. The choice of jurisdiction will also determine a creditor’s right to set off claims on the insolvent bank against amounts that it owes the bank. The Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) case revealed striking differences across members of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS 1992). Similarly, the ability to exercise close-out netting provisions under the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) master contracts may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, although ISDA has achieved a remarkable degree of international harmonization and has recently agreed to modify its close-out netting procedures for dealer banks to facilitate an orderly resolution (ISDA 2014).

The outcome of insolvency proceedings will also depend on the powers and obligations of the resolution authority, which may differ from country to country. For example, does the resolution authority have the power to impose “haircuts” on the claims of creditors without a lengthy judicial proceeding? Does the resolution authority have the ability (and access to the necessary resources) to provide access to adequate liquidity or a capital injection?10 With regard to banks, is the resolution authority constrained to choose the least costly resolution method, as in the United States? Or is the resolution authority obliged to give preference to domestic depositors, as the law requires in Australia and the United States? More fundamentally, what is the objective of the supervisory intervention and the resolution process?

In an effort to reduce these differences in resolution policies and procedures across countries, the FSB has negotiated a set of Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions that each member country should implement (FSB 2011, 2012, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c, 2014). The FSB has concluded that an effective resolution regime should:

1. Ensure continuity of systemically important functions

2. Protect insured depositors and ensure rapid return of segregated client assets

3. Allocate losses to shareholders and to unsecured and uninsured creditors in a way that respects payment priorities in bankruptcy

4. Deter reliance on public support for solvency and discourage any expectation that it will be available

5. Avoid unnecessary destruction of value

6. Provide for speed, transparency, and as much predictability as possible based on legal and procedural clarity and advanced planning for orderly resolution

7. Establish a legal mandate for cooperation, information exchange, and coordination with foreign resolution authorities

8. Ensure that nonviable firms can exit the market in an orderly fashion

9. Achieve and maintain credibility to enhance market discipline and provide incentives for market solutions

Many of these attributes can be read as attempts to establish a new regime that would prevent another disorderly, Lehman-like bankruptcy. The emphasis is on planning, sharing of information, cross-border cooperation, the protection of systemically important functions, and avoidance of any unnecessary destruction of value. All of these goals will be difficult to achieve, especially because some of the G20 countries have not yet established special resolution regimes for complex, international financial institutions.

Perhaps the greatest challenge, however, is to achieve credibility. The authorities tend to be judged by what they do, not by what they say, and most of the interventions and resolutions that occurred during the crisis were chaotic, without the benefit of careful planning for an orderly liquidation or restructuring process. They failed to allocate losses to unsecured and uninsured creditors, involved major commitments of public funds, and showed little evidence of substantial cross-border cooperation. None of these interventions could be described as speedy, transparent, or predictable.

The FSB’s effort to enhance credibility, however, is not advanced by the vague way in which it describes the point at which resolution should take place (FSB 2011, p. 7): “Resolution should be initiated when a firm is no longer viable or likely to be no longer viable, and has no reasonable prospect of becoming so.” Although the clear intent is for the authorities to intervene before equity is wiped out, the clause “has no reasonable prospect of becoming so” can be very permissive. Given the demonstrated tendency of managers, accountants, and supervisors to take an overly optimistic view of a firm’s prospects for recovery, this clause seems to provide scope for delaying intervention until long after a firm’s equity has been destroyed. Deep insolvencies increase the likelihood of an ad hoc improvised resolution to offset the market reaction to the realization that early intervention has not worked. The remainder of this chapter focuses on one aspect of credibility: the prospects for cross-border cooperation, the essential foundations for which are addressed by the seventh goal listed above.

The Crucial Role of International Cooperation

The fundamental challenge to a cooperative resolution is that national authorities will inevitably place a heavier weight on domestic objectives in the event of a conflict between home and host authorities. Three asymmetries between the home and host country may create problems even if procedures could be harmonized to conform to the Key Attributes. First is asymmetry of resources: supervisory and resolution authorities may differ greatly in terms of human capital and financial resources, implying that the home supervisory authority may not be able to rely on the host supervisory authority (or vice versa) simply because it may lack the capacity to conduct effective supervisory oversight and an effective resolution. Second, asymmetries of financial infrastructure may give rise to discrepancies in the quality of supervision across countries. Weaknesses in accounting standards and the quality of external audits may impede the efforts of supervisors just as informed, institutional creditors and an aggressive and responsible financial press may aid them. The legal infrastructure matters as well. Inefficient or corrupt judicial procedures may undermine even the highest quality supervisory efforts.

Perhaps the most important conflict, however, arises from asymmetries of exposures: what are the consequences for the host country and the home country if the entity should fail? Perspectives may differ with regard to whether a specific entity jeopardizes financial stability. This will depend on whether the entity is systemically important in either or both countries and whether the foreign entity is economically significant within the parent group.

In order to enhance prospects for a cooperative resolution, the leading resolution authorities have been actively engaged in supervisory colleges and crisis management groups organized by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and FSB and have signed several memoranda of understanding with their counterparts. But it remains to be seen how effective these measures will be under the stress of an actual crisis.

One solution might be to harmonize resolution regimes across the world. The Key Attributes approach is, in fact, a modest step in that direction,11 but when the question of allocating losses arises few people have confidence that this approach would hold up. Countries are understandably reluctant to allocate losses ex ante—no country is willing to make an open-ended fiscal commitment. And cross-border losses will be even more difficult to allocate ex post since it will always be possible to argue that the losses would not have occurred if home country supervision had been more effective.12

Even if the Key Attributes were implemented in all of the major banking centers, the FSB document does not have the status (or enforceability) of a multilateral international treaty. The Key Attributes cannot solve the basic problem: if the top-tier entity in a group were to go into default, its branches, subsidiaries, and affiliates in host jurisdictions around the world might all be called into default, either immediately or upon a consequent run by creditors and counterparties.13 Courts in these host countries might be asked to ring-fence assets, freeze payments, and set aside rulings by the home country authorities. The problem, of course, is that legal procedures—and, indeed, the objectives of an insolvency system—differ across countries. Moreover, it would not be possible for the authorities in such proceedings to be bound by ex ante commitments between the home and host countries because, in many cases, it may not be possible to know in advance which authority will be asked to rule.

A more fundamental solution would be to harmonize national insolvency laws and deal with any G-SIB failure in a unified global proceeding that would treat all creditors equally, strictly according to contractual priorities and without discrimination in favor of local claimants. Although various groups have worked on proposals to harmonize insolvency laws for decades, scant progress has been made. Indeed, the obstacles under current circumstances seem insuperable.

Even though a global solution is not possible, some progress could be made with bilateral agreements. Indeed, the FDIC and the Bank of England published a memorandum of understanding in 2012 agreeing to consult, cooperate, and exchange information relevant to the conditions and possible resolution of financial service firms with cross-border operations (FDIC and BoE 2012). Since most US cross-border transactions involve entities chartered in the United Kingdom, this agreement could enhance the prospects for an orderly resolution of G-SIBs headquartered in the United States. But the memorandum does not create any legally binding obligations and, in the past, close relations between the authorities in the United States and the United Kingdom have not been sufficient to ensure a cooperative solution to cross-border banking problems.14

Scott (2015) has advanced a novel proposal to add greater certainty about how a resolution involving the United States might proceed and provide an incentive for other countries to cooperate. The approach would avoid the enormous obstacles to negotiating a multilateral treaty by substituting a provision in Chapter 15 providing for US enforcement of foreign country stay orders and barring domestic ring-fencing actions against local assets, provided that the foreign country adopts similar provisions for US proceedings. Such an agreement with the United Kingdom might reduce a considerable amount of uncertainty regarding the resolution of a G-SIB based in the United States. But, as a member of the European Union, the United Kingdom would find it difficult to make a separate agreement with the United States.15

Paul Tucker (2014) has suggested an alternative, contractual approach by “hard-wiring” how a cross-border resolution would proceed in the structure of a group’s liabilities. Any losses in a foreign subsidiary exceeding the equity in that subsidiary would be transferred to a higher level entity16 within the group by writing down (converting into equity) a super-subordinated debt instrument held by that higher level entity. The host authorities could trigger the intra-group debt conversion if conditions to put the subsidiary into local liquidation or resolution were met.17 The merit of this approach is that it would force home and host authorities to agree upfront about how they will coordinate the resolution of a global group. Tucker emphasizes this would mean nations “find out ex ante whether they can co-operate on that hard-wiring, rather than, as in the recent crisis, finding out ex post whether they can cooperate in a more ad hoc resolution.”18 In the absence of trust between the home and host authorities, the home authority will be unwilling to permit the host authority to trigger an intra-group conversion of debt into equity.

Without a robust cross-border agreement for resolving G-SIBs, countries are taking precautions that will enable them to ring-fence the parts of a banking group that are within their borders. The United States, for example, has required that foreign banks with substantial operations in the United States establish a US holding company that would be subject to prudential rules there, including capital adequacy requirements, and could, in principle, be resolved in the United States if the home country’s resolution procedures did not seem to treat US interests fairly. Other countries are requiring that G-SIBs “pre-position” capital and liquidity in the entities operating within their borders (often including branches). This has the effect of providing an additional buffer against losses in the host country and facilitates a host country resolution if necessary.

Implications of Ring-Fencing for the Corporate Structure of G-SIBs

If the home country resolution authority has the legal power and resources to resolve an entire G-SIB, it might prefer that the G-SIB operate through a single legal entity if only to minimize the costs of coordinating actions with scores of other resolution authorities.19 Of course, this approach will succeed only if all host country regulatory authorities expect that their national interests will be treated equitably vis-à-vis residents of the home country and residents of other countries. If not, they have the right (and possibly the legal obligation) to intervene to protect local interests.

G-SIBs, particularly those that specialize in wholesale activities, tend to prefer the flexibility of a more centralized organizational structure even though they will want to establish a number of subsidiaries to take advantage of particular regulatory and tax incentives and to facilitate internal managerial goals. The advantages of conducting all banking business through a single entity are compelling.20 Unconstrained by the legal lending limits in individual countries, the G-SIB would have a larger capacity to serve the needs of its customers in any location. Moreover, the ability to exercise central control over capital and liquidity will enable the G-SIB to respond more flexibly to the changing environment. It will reduce the resources that need to be allocated to liquidity so long as the needs of various offices are not perfectly correlated. To the extent that it achieves diversification benefits across its branch offices, the G-SIB may be able to operate safely with less capital and liquidity than if it were required to allocate capital separately to each entity to achieve the same degree of safety.

The possibility of ring-fencing by the host country, however, means that this flexibility may disappear in a crisis, when it is most needed.21 Since neither the home country nor host countries can guarantee that ring-fencing will not occur, the single entity model is not prudent.

Although operation through a single legal entity is neither feasible nor prudent, one model of corporate structure attempts to capture many of the benefits even though the G-SIB would operate through several separately incorporated subsidiaries. This “centralized” model emphasizes management of liquidity, capital, and risk exposures as well as information technology and processing from the top-tier entity. So far as local regulations will permit, subsidiaries would be managed as if they were branches and lines of business would be managed to maximize profits without regard for the legal entities in which the activities are conducted.

The anticipated benefit is not only enhanced flexibility, but also the belief that the top-tier entity can manage an internal capital market that will fund the activities of G-SIBs at lower cost than if each operating entity were obliged to raise funds in each local market. In addition, centralized management of technology and operational resources should enable the group to achieve greater economies of scale than if these resources were dispersed to the various operating units in which the services are needed. This approach results, of course, in a mismatch between legal structures and operating structures that is likely to cause serious difficulties if the G-SIB needs to be resolved.

If ring-fencing is expected to be the rule, not the exception, then each national resolution authority would be responsible for resolving banks that reside in its jurisdiction. Under this assumption, foreign branches would be treated as if they were subsidiaries (which, in fact, is the case in some jurisdictions) and G-SIBs would be obliged to operate through “decentralized” or “subsidiarized” models. In this approach, the top-tier institution manages a network of local subsidiaries that operate under a common brand. Each subsidiary, however, is funded locally and governed (within constraints) by local directors. Shares in the subsidiary may be listed on the local stock exchange although, of course, the parent entity will maintain a controlling interest.

Among G-SIBs, BBVA, HSBC, and Santander have endorsed this organizational model. They regard this as a source of strength and stability as well as a way of enhancing the resolvability of the group. Each significant foreign subsidiary not only meets local capital requirements, but also maintains excess capital to meet local growth objectives and provide a buffer against most losses. In addition, each subsidiary manages its liquidity needs without relying on funds or guarantees from the parent. Consistent with the emphasis on local funding, exposure to credit risk is focused on local borrowers and is usually denominated in local currency so that cross-border credit risk exposures are relatively small. From the perspective of the host country resolution authorities, the subsidiary should be autonomous and able to stand alone in the event the rest of the group experiences financial distress.

Although the parent will have an ownership position and may provide bail-in debt, the subsidiary should not rely on the parent or on access to the parent country central bank for its liquidity needs. But even this degree of financial autonomy may not be sufficient to accomplish the main objective of a policy of subsidiarization: to ensure that a legal entity can continue to operate even though its parent may be insolvent. Or, if the legal entity itself should become non-viable, to ensure that it may be resolved at relatively low cost and its systemically important services continued. This requires limits on inter-affiliate interdependencies of all sorts. The host authority must be assured that the subsidiary will continue to have access to services that may be supplied by other entities in the group or outsourced.22

One can debate whether constraints put on interactions between the parent and affiliates provide useful firewalls or, in times of crisis, ignite walls of fire. Certainly control over an autonomous subsidiary gives the host country the ability to preserve the assets of the local subsidiary for the benefit of local creditors and to implement an orderly resolution if necessary. But it may reduce the likelihood that the subsidiary will receive support from the parent, if it should encounter difficulties.

The appropriate degree of insulation involves striking a balance between the benefits of capital market mobility in normal times, versus insulation from external shocks in a crisis. In general, a subsidiary that is free to engage in transactions with affiliates can fund itself more cheaply in normal times if only because the parent treasury function will be able to draw its funding from a broader array of markets. But in times of crisis involving the rest of the group, the ability of the subsidiary to fund itself may be the key to its survival. Unfortunately, it is unlikely that a subsidiary could make a rapid transition from one mode of funding to another as circumstances dictate. Access to local funding usually requires the cultivation of local relationships and access to local market infrastructure.

The issue of shared services is a bit different because it appears that institutions can avoid making a trade-off between autonomy and efficiency. A subsidiary that is constrained to develop its own back office, information technology, risk management systems, and other operational infrastructure is likely to face unnecessarily high costs because it cannot achieve scale economies. Since the host country’s interest should be in ensuring that the subsidiary has uninterrupted access to such services, not in who owns the infrastructure, it is possible to address this issue in other ways. If the parent houses technology-intensive services in bankruptcy-remote entities, then the host country can have some degree of comfort that the subsidiary will be able to continue its access to essential services even if the parent experiences financial distress. The credibility of this arrangement is greater if the service subsidiary adopts a business model that will enable it to reduce costs rapidly whenever its revenues fall.

Subsidiarization does improve the alignment between legal entities and the way in which the business is conducted. Moreover, provided that the subsidiary is largely autonomous from the rest of the group, it could be readily spun off to facilitate an orderly resolution. Relative to the centralized model, the decentralized approach appears to better facilitate an orderly resolution, if only because it should be easier to recapitalize and privatize an autonomous subsidiary.

Concluding Comment

In the absence of an official consensus on the appropriate model for cross-border resolution, G-SIBs continue to operate under both centralized and subsidiarized models depending on their strategic preferences and the scope for choice provided by host and home regulatory authorities. Corresponding to these differing organizational models, two approaches to cross-border resolution have been endorsed by the FSB: a single-point-of-entry strategy (SPE) and a multiple-point-of-entry strategy (MPE).

The SPE model was proposed in a joint paper by the Bank of England and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC and BoE 2012). It tries to finesse the complexities of dealing with a welter of intermediate holding companies and subsidiaries by focusing the resolution process on the top-level holding company. Whenever a foreign subsidiary fails to meet its regulatory capital requirements, the top-level holding company will be responsible for recapitalizing the subsidiary. If the loss at the subsidiary is so large that it exceeds the holding company’s debt claims on the subsidiary and its ability to provide additional resources, the top-level holding company will be placed into receivership.23 The aim is to financially restructure the holding company while keeping the operating subsidiaries of the holding company open. The assets of the failed holding company are transferred to a newly created bridge financial company, with most of the liabilities left behind in the bankruptcy proceedings. Temporary liquidity support can be provided if necessary, but taxpayers must be insulated from any potential loss. In principle this will permit the G-SIB’s operating subsidiaries to continue without interruption and provide time for the resolution authorities to restructure the bridge bank and spin it off to the public.

The SPE depends on three critical assumptions: (1) the bank holding company will have sufficient debt at the top tier to be able to recapitalize a faltering subsidiary;24 (2) host country authorities will permit the home country resolution authority to control the process; and (3) the resolution authority will have access to sufficient liquidity to maintain the critical operations of subsidiaries in the group while the restructuring of the top-level institution takes place. The latter may be an issue in several countries that are home to institutions with liabilities that are a substantial multiple of their gross domestic products.

This approach faces a tricky problem in a scenario in which a foreign subsidiary is the major source of losses and should be liquidated, as noted by Scott (2015). The authorities, of course, do not want to be in the position of propping up an institution that has no going-concern value. But once they admit the possibility that some foreign subsidiaries may not be protected, creditors have reason to be concerned about all of the foreign subsidiaries and it may not be possible to implement the resolution without creating spillovers as creditors engage in a flight to quality.

In addition to the hope that foreign authorities can be convinced to forbear and leave the resolution to the headquarters authority, the laws underlying many financial contracts will need to be changed or the single resolution authority will need to have the ability to impose a stay. Otherwise the initiation of resolution proceedings with regard to the top-level entity could be interpreted as an event of default that permits counterparties to terminate their financial contracts. This could destabilize markets and frustrate the attempt of the single resolution authority to ensure the continuity of operations.

The multiple-point-of-entry strategy relies on three critical assumptions: (1) that the failing subsidiary will have sufficient bail-in debt to recapitalize the viable part of the institution without relying on taxpayer assistance;25 (2) that the remaining subsidiaries of the group will not suffer a loss of market confidence because of the resolution of an affiliate institution; and (3) that other countries will not use the initiation of the resolution process in one country as a rationale for intervening in affiliates of the group in their jurisdictions. Although this approach has obvious appeal for G-SIBs that are not organized within a holding company structure, based on the past behavior of market participants it appears to make a very optimistic assumption that creditors and counterparties of affiliates will not regard the resolution of one subsidiary as a signal that the entire group is in jeopardy. And if markets do not have confidence that the problem can be isolated to one subsidiary, the authorities may feel obliged to provide a bailout to preserve financial stability.

Neither strategy is certain to succeed, but maintaining the possibility that either might be employed (as envisaged for example by the new European legislation on bank crisis resolution) does not help the market to price and monitor the risk of default. In fact, if the market is surprised by the resolution strategy the authorities employ, confidence in the system may be undermined, leading to panicky reactions that will impede an orderly resolution.26 If creditors and investors cannot anticipate the endgame, they cannot price risk efficiently. Ultimately, this uncertainty is likely to be destructive to markets and to the banks themselves, and to exacerbate the risk of disorderly resolution.

Despite an enormous amount of effort, one must conclude that we do not yet have a reliable framework to undertake the orderly resolution of a G-SIB. More effective bankruptcy procedures like the proposed Chapter 15 reform would certainly help provide a stronger anchor to market expectations about how the resolution of a G-SIB may unfold. Greater clarity of corporate and business structures and a greater degree of subsidiarization would facilitate any resolution process. Although too-big-to-fail is too-costly-to-continue, a solution to the problem remains elusive.

References

Avraham, D., P. Selvaggi, and J. I. Vickery. 2012. “A Structural View of U.S. Bank Holding Companies,” Economic Policy Review 18, no. 2 (July 16): 65–81.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS). 1992. The Insolvency Liquidation of a Multinational Bank, BCBS Compendium of Documents, International Supervisory Issues III (May 2001).

Baxter, T., and J. Sommer. 2005. “Breaking Up Is Hard to Do: An Essay on Cross-Border Challenges in Resolving Financial Groups,” in Systemic Financial Crises: Resolving Large Bank Insolvencies, ed. D. Evanoff and G. Kaufman (Singapore: World Scientific), 175–91.

Carmassi, J., and R. J. Herring. 2013. “Living Wills and Cross-Border Resolution of Systemically Important Banks,” Journal of Financial Economic Policy 5, no. 4: 361–87.

Carmassi, J., and R. J. Herring. 2014. Corporate Structures, Transparency and Resolvability of Global Systemically Important Banks, Systemic Risk Council, Washington, DC.

Carmassi, J., and R. J. Herring. 2015. The Corporate Complexity of Global Systemically Important Banks, working paper, Wharton Financial Institutions Center.

Cumming, C., and R. Eisenbeis. 2010. Resolving Troubled Systemically Important Cross-Border Financial Institutions: Is a New Corporate Organizational Form Required?, working paper, Wharton Financial Institutions Center, February.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and Bank of England (BoE). 2012. Resolving Globally Active, Systemically Important Financial Institutions, a joint paper by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and the Bank of England, December 10.

Financial Stability Board. 2011. Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions, October.

Financial Stability Board. 2012. Resolution of Systemically Important Financial Institutions— Progress Report, November.

Financial Stability Board. 2013a. Recovery and Resolution Planning for Systemically Important Financial Institutions: Guidance on Developing Effective Resolution Strategies, July 16.

Financial Stability Board. 2013b. Recovery and Resolution Planning for Systemically Important Financial Institutions: Guidance on Identification of Critical Functions and Critical Shared Services, July 16.

Financial Stability Board. 2013c. Recovery and Resolution Planning for Systemically Important Financial Institutions: Guidance on Recovery Triggers and Stress Scenarios, July 16.

Financial Stability Board. 2014. Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions, October.

Gracie, A. 2014. “Making Resolution Work in Europe and Beyond—the Case for Gone Concern Loss Absorbing Capacity.” Speech given at a Bruegel Breakfast Panel Event, Brussels, July 17.

Haldane, A. 2009. Banking on the State, paper based on presentation to the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, September 25.

Herring, R. J. 1993. “BCCI: Lessons for International Bank Supervision,” Contemporary Policy Issues 11 (April).

Herring, R. J. 2002. “International Financial Conglomerates: Implications for Bank Insolvency Regimes,” in Policy Challenges for the Financial Sector in the Context of Globalization, Proceedings of the Second Annual Policy Seminar for Deputy Central Bank Governors, Federal Reserve Bank/IMF/World Bank.

Herring, R. J. 2003. “International Financial Conglomerates: Implications for National Insolvency Regimes,” in Market Discipline in Banking: Theory and Evidence, ed. G. Kaufman (Elsevier), 99–130.

Herring, R. J. 2007. “Conflicts between Home and Host Country Prudential Supervisors,” in International Financial Instability: Global Banking and National Regulation, ed. D. Evanoff, G. Kaufman, and J. LaBrosse (World Scientific), 201–19.

Herring, R. J. 2013. “The Danger of Building a Banking Union of a One-Legged Stool,” in Political, Fiscal and Banking Union in the Eurozone, ed. F. A. Allen, E. Carletti, and J. Gray (FIC Press).

Herring, R. J., and J. Carmassi. 2010. “The Corporate Structure of International Financial Conglomerates: Complexity and Its Implications for Safety & Soundness,” in Oxford Handbook of Banking, ed. A. N. Berger, P. Molyneux, and J. O. S. Wilson (Oxford University Press).

Huertas, T. F. 2009. “The Rationale and Limits of Bank Supervision,” unpublished manuscript.

Huertas, T. F. 2010. “Too Big to Fail Is Too Costly to Continue,” Financial Times, March 22, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/62e80b1a-35d8-11df-aa43-00144feabdc0.html .

Huertas, T. F. 2014. Safe to Fail: How Resolution Will Revolutionise Banking (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). 2014. Major Banks Agree to Sign ISDA Resolution Stay Protocol, October 11, http://assets.isda.org/media/de778136/58b5618f.pdf.

Kapur, E. 2015. “The Next Lehman Bankruptcy,” chapter 7 in this volume.

King, M. 2010. Banking from Bagehot to Basel, and Back Again, Second Bagehot Lecture, Second Buttonwood Gathering, New York, October 25.

Mayes, D. 2013. “Achieving Plausible Separability for the Resolution of Cross-Border Banks,” Journal of Financial Economic Policy 5, no. 4: 388–404.

Miller, H. R., and M. Horwitz. 2013. Resolution Authority: Lessons from the Lehman Experience. Weil, April 11.

Omarova, S. 2013. Large U.S. Banking Organizations’ Activities in Physical Commodity and Energy Markets: Legal and Policy Considerations, Written Testimony before the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Protection, July 23.

Scott, K. 2015. “The Context for Bankruptcy Resolutions,” chapter 1 in this volume.

Tucker, P. (2014). “The Resolution of Financial Institutions without Taxpayer Solvency Support: Seven Retrospective Clarifications and Elaborations,” speech delivered to the European Summer Symposium in Economic Theory, Gerzensee, Switzerland, July 3.

1. For example, both the Bank of England and the International Monetary Fund had identified sixteen LCFIs that were crucial to the functioning of the world economy. See Herring and Carmassi (2010) for a discussion of this classification approach. It should be noted that the indications of the kinds of problems that would need to be dealt with in the resolution of an LCFI were apparent long before the crisis (Herring 2002, 2003).

2. Huertas (2009) made the point in more detail: “The Lehman bankruptcy demonstrates that financial institutions may be global in life, but they are national in death. They become a series of local legal entities when they become subject to administration and/or liquidation.”

3. The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers provided a particularly stark illustration of this problem. The resolution of Lehman Brothers involved more than one hundred bankruptcy proceedings in multiple jurisdictions. Because crucial data centers were sold with one of the entities, other affiliates (and their resolution authorities) lost access to fundamental information about who owed what to whom. See Kapur (2015) for a remarkably detailed analysis.

4. Haldane (2009) estimated that at the height of the crisis over $14 trillion (about one-quarter of world GDP) had been committed by the United States, the United Kingdom, and the euro area to support their banking systems.

5. Although in common use, this term is regrettably imprecise. Size is one, but not the only, attribute of such institutions. It should be interpreted as a proxy for institutions that are also too interconnected, too complex, too international in scope or too important to be resolved in an orderly fashion. A cynic might also add that many of these institutions appear to have been too big to manage.

6. Carmassi and Herring (2015) present evidence suggesting this correlation may be spurious and disappear when the M&A history of G-SIBs and time effects are taken into account.

7. Note that the number of subsidiaries indicated for the largest US bank holding company in figure 1.A is taken from a different database, the National Information Center (Federal Reserve), which uses a lower threshold for determining control and a different methodology. Disclosure practices are so ineffectual that an unfortunate degree of uncertainty remains about the number of subsidiaries controlled by each G-SIB, something that should be straightforward to measure and report. See Carmassi and Herring (2014) for a broader discussion of sources of data.

8. For example, Lehman Brothers had more than six thousand subsidiaries when it entered bankruptcy. During the bankruptcy proceedings it was determined that fewer than one thousand had any active relationship to the ongoing business. Although it would certainly be more difficult to resolve seven thousand entities, even one thousand present a formidable challenge (Miller and Horwitz 2013).

9. For additional details regarding the activities of US G-SIBs in physical commodity and energy markets, see Omarova (2013).

10. The FSB agreement on Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions and the recent FSB proposed requirement for Total Loss Absorbing Capacity attempt to minimize the likelihood that such interventions might be necessary.

11. The step is only a modest one because the document leaves considerable room for variation across countries to accommodate differences in institutional structure and regulatory traditions.

12. There is probably no better example of this problem than the reluctance of the European Union to adopt a common deposit insurance fund even though it is widely recognized that the link between the safety of bank deposits and country risk can pose a major threat to the integrity of the euro area. So long as the safety of a deposit in the eurozone depends on the strength of the deposit insurance system and the creditworthiness of the country where the deposit was placed, the lethal link between bank risk and country risk cannot be broken (Herring 2013).

13. This may be precipitated by ipso facto clauses that permit contracts to be terminated based on a change of control, bankruptcy proceedings, or a change in agency credit ratings. Under pressure from the authorities, ISDA has adopted a protocol to permit a limited stay in implementing the close-out netting clauses with the eighteen major dealer banks (ISDA 2014). This brief stay provides additional time for the authorities to arrange an orderly transfer of these contracts. Until this agreement takes effect, however, counterparties may liquidate, terminate, or accelerate qualified financial contracts of the debtor and offset or net them under a variety of circumstances. This can result in a sudden loss of liquidity and, potentially, the forced sale of illiquid assets in illiquid markets that might drive down prices and transmit the shock to other institutions holding the same assets.

14. See, for example, the case of BCCI (Herring, 1993) and the more recent Lehman Brothers bankruptcy (Kapur 2015).

15. Moreover, the usual measures of the importance of cross-border transactions with the United Kingdom may overstate its importance in resolution. Many US G-SIBs have chosen to form subsidiaries in the United Kingdom because under EU rules they may then branch into any other member of the European Union. Thus US subsidiaries headquartered in the United Kingdom may have significant assets in the rest of the European Union that could be ring-fenced by the host authorities.

16. This is the basic mechanism through which the single-point-of-entry approach to resolution would work. Tucker (2014) argues, however, that the same principle applies to bail-in debt in a multiple-point-of-entry strategy.

17. As Tucker (2014) notes, “The host authority for a key subsidiary must have a hand on the trigger for converting intra-group debt into equity. If the home country alone controlled the trigger, host authorities would likely be worried that the home authorities might not, in fact, pull the trigger.”

18. If the home authorities will not require that the responsible higher level entity issue a minimum amount of bail-in debt or if they will not agree to a trigger in the hand of host authorities that would allow excess losses to be transferred to the higher level entity, the host authority will conclude that the home authority is either unable or unwilling to implement a whole-group resolution.

19. Cumming and Eisenbeis (2010) propose that G-SIBs be required to operate as a single legal entity.

20. And they may include the benefits of an implicit government subsidy if a G-SIB continues to be viewed as too complex to fail.

21. This is one of the major flaws in the Basel approach to consolidated bank capital regulation. If resources cannot be moved from one entity to another affiliate when needed, then a regulatory focus on consolidated capital can be misleading.

22. Of course, the host country authorities must take care not to require insulation so extreme that it would undermine any economic rationale for operating a G-SIB and minimize any benefit to the host country.

23. Note that Scott (2015) raises the pertinent question of how the decision would be made to recapitalize the failed subsidiary.

24. Of course, the host country authority must have confidence that the parent holding company will be willing (or will be compelled by the home country authority) to sustain the operations of a local subsidiary in financial distress.

25. See Huertas (2014) for a lucid description of how a subsidiarized bank should be resolved in an orderly manner.

26. Gracie (2014) emphasizes the point that transparency regarding the resolution process is essential to creditors and investors.