![]()

As wine towns go, Neviglie is not one of the main stops on a tour of Piedmont. But it should be, if only for the view: It sits just outside the Barbaresco DOCG zone, at an elevation of around fifteen hundred feet, looking out over the Barbaresco vineyards of Treiso to the west and Neive to the north. Farther south are the wine towns of Barolo, poking through shrouds of mist from their hilltop perches. And farther still are the Maritime Alps that shut Piedmont off from France, the rumpled ridges shimmering white with snow even in the dead of summer.

This is the panorama from Walter Bera’s small cantina in Neviglie, where he makes a little bit of everything; plump, fruity reds from dolcetto and barbera, plus a great Asti spumante, are among the wines we’re sipping in his cool cellar. He’s not a famous producer, but instead one of thousands of small-scale vintners who work the hills around the towns of Alba and Asti, making wines that would get far more critical attention if they were made in a less populous region. His winery is just up the hill from his home, and after a half-hour or so of tasting we head back toward the house for some of his homemade sausage.

But there’s a problem. When we went into the cellar it was bright and sunny, albeit very humid. Yet as we come back outside, a mass of clouds is moving in over Treiso like a giant brushstroke. It’s as if the sky has been divided in half, one side white and one black. “O dìo,” Walter says. “That doesn’t look good at all.”

Hail is always a looming threat in wine zones such as Barolo and Barbaresco, which sit in the Langhe hills of southeastern Piedmont. It’s a region shaped by rivers such as the Tanaro and Belbo, which flow down from the Maritime Alps separating Piedmont and Liguria. The particular positioning of the Langhe hills leaves them vulnerable to wet weather throughout the summer and fall.

Standing quietly in Walter’s driveway, looking out at the patchwork of vineyards blanketing the soft contours of Treiso, we hear the first reports from what might be called the guns of Barbaresco: a series of air cannons that shoot sound waves into the clouds. Wine lore is full of nineteenth-century vignerons pointing their old, creaky cannons to the skies, blasting at the clouds to try and shatter the stones inside. Evidently, this seemingly superstitious practice lives on in a new, high-tech incarnation. Walter says that wine producers throughout the Barbaresco zone chipped in to buy the cannons, which are now thundering away at regular intervals. Each blast is followed by a warbling, whistling sound, like the strange music a saw blade makes when it is shaken. The booming of the cannons echoes through the hills. With all the gray clouds hovering overhead, the Langhe looks and sounds like some fiery battlefield.

“The idea, I guess, is that the waves not only break up the hail but move the clouds along,” Walter explains. From our lofty perch we can see the storm moving toward us, and soon the hail is pockmarking the earth at our feet. We take cover in the winery and listen to the stones battering the roof. “They don’t sound big,” Walter says, trying to remain good-humored as the storm hovers overhead, threatening his livelihood.

Luckily, it is a brief hit. We take a quick walk through the vineyards to survey the damage, and it looks fairly minor: some shredded leaves, some ruptured grapes, but nothing too bad, although a few of the bunches will probably rot now that their skins have burst. The cannons are still booming and whistling away as the roiling sea of Langhe vineyards—probably the densest concentration of vines anywhere in Italy—begins to glisten in the shafts of sunlight now piercing the clouds.

Walter picks up a nugget of hail and examines it, almost bemusedly. It’s no exaggeration to say that five minutes of hail could have wiped out the whole year’s production. Maybe those shock waves did break it up on its way down. It seems highly unlikely. But in a place like the Langhe, where wine is everything, hail calls for drastic measures. If the big guns are what it takes to win the war, so be it.

Piedmont, more so than even Tuscany, is the wine-lover’s mecca. It is often referred to as Italy’s answer to Burgundy—still a farmstead wine culture compared to more developed wine regions such as Tuscany. What sets Piemontese towns such as Alba and Asti apart is that people go there almost exclusively for the wine and food. Their scents alone are enough to draw you in, like some cartoon character being pulled along by the vapors of a pie warming on the windowsill. In the Langhe hills it’s the aromas—of truffles, mushrooms, hazelnuts, coffee, and above all else, Barolo and Barbaresco wine—that sweep people off their feet.

Although there are a number of noteworthy vineyards in the Alpine foothills of northern Piedmont, the main concentration of wine activity is in the Langhe and Monferrato hills to the southeast, which spill through the towns of Alba, Asti, and Alessandria en route to the plains flanking the Po River. Alba and Asti are set among hills so densely planted to vines, in parcels so fragmented, that it’s hard to imagine any other commercial activity in the region other than viticulture. In fact, Alba’s only real industry is a small textile factory and the Ferrera chocolate plant, makers of Nutella. Other than that, it’s all about wine.

“When you go into a bar around here, chances are the people aren’t talking about politics or the football game,” says Alberto Chiarlo, export director for the well-known Michele Chiarlo estate. “They are talking about wine. There is an enoteca around every corner in the Langhe.”

The concentration of vineyards and wineries in Piedmont is remarkable. The entire surface area of the village of Barbaresco, one of three adjacent communes that comprise the Barbaresco DOCG, is about seventeen hundred acres, of which roughly twelve hundred are planted to vineyards. There are more than eight hundred bottlers of Barolo and Barbaresco wine in Piedmont, each of them squeezing a relatively tiny amount of wine from their (mostly small) vineyards. Based on figures compiled by Italy’s Ministry of Agriculture, the average size of a Barolo/Barbaresco vineyard is about five acres, with an average annual production of about ten thousand bottles. That is minuscule by today’s standards. There are scores of individual wineries throughout Italy that produce more than the Barolo and Barbaresco zones combined, and then some.

Piedmont has more DOC zones (fifty-two) than any other Italian region, and more history and nuance to its wines than could possibly be summed up easily. It really has to be seen to be believed, and must be experienced to be appreciated. What follows is a thumbnail sketch to get you started on what may become—as it has for many Italophiles—a lifelong obsession.

For all of the prestige and mystique of dry red Barolo and Barbaresco, the wines that have long driven the Piedmontese wine economy are sweet, white spumanti and frizzanti, made from moscato bianco grapes in the hills southeast of Asti. Even today, with sweet sparklers seemingly out of fashion, the DOCG of Asti is the most productive single wine zone in Italy. In 1999, production of sparkling Asti Spumante and semisparkling, or frizzante, Moscato d’Asti topped 650,000 hectoliters (about 17 million gallons). And this despite an entire generation of wine snobs turning up their noses at these fun, fruity, and often surprisingly complex wines. (Since Asti Spumante and Moscato d’Asti often toe a fine line between dry and sweet, they are discussed here instead of in the Sweet Wines section below.)

Like the lambrusco grape of nearby Emilia-Romagna, the moscato of Asti has become, to some extent, a victim of its own success. People remember the cheesy television ads for Martini & Rossi Asti Spumante—a perfectly pleasurable, if mass-produced, wine—and think of themselves as uncool if they deign to drink such things. While it is true that the wines of Asti can be cloyingly sweet, the category shouldn’t be written off altogether.

In fact, there may be no more direct link to the winemaking traditions of centuries past than a frizzante wine. At one time, farmer-winemakers simply tossed super-ripe grapes into open-topped wooden vats and let the grapes ferment naturally, creating wines that were sweet, syrupy, oxidized, and often fizzy. It was not uncommon for fermentations to stop during the cold winter months and then start up again as ambient temperatures rose during the springtime, which naturally created bubbles in the wine. In many cases, farmers would try to bottle these wines, only to have them explode as the secondary fermentations caused carbon dioxide pressure to build in the bottle.

The production of fizzy wines is more controlled these days. Producers of modern frizzante arrest the fermentation, usually by rapidly chilling the fermenting juice so that the yeast stops working. This is how the wine retains its balance of natural bubbles and residual sugar.

The main difference between a frizzante and a full-on spumante is that the fermentation of a frizzante is arrested earlier, usually at an alcohol content of between 4 and 6 percent. At this level the fermentation has not yet gotten to a full boil, so the carbonation is gentler and the wine richer in sugar. Conversely, a spumante is allowed to reach alcohol levels of up to about 9 percent before it is chilled down, creating a wine higher in alcohol, with more effervescence and less residual sugar. Technically speaking, an Asti Spumante should be crisper and more aromatic and a Moscato d’Asti softer, plumper, and sweeter. But it doesn’t always work out that way. As with any wine, the best Asti Spumante and Moscato d’Asti are marked by balance—in this case, a balance of peach-and-apricot sweetness with a cleansing surge of acidity.

Like the off-dry Prosecco of the Veneto, Asti Spumante—some of which is made in the classic Champagne method, where the wine undergoes its secondary fermentation in bottle—can be a mouthwatering apéritif. The typically fuller, fruitier Moscato d’Asti is more often reserved for desserts, especially dryer cakes such as panettone, where the delicate peachy sweetness of the wine isn’t drowned out in a clash with an equally sweet dish. The lower alcohol levels of both Asti wines make them easier to place within a multicourse meal, whether as apéritifs or accompaniments to desserts. They aren’t as overwhelming as fortified wines (such as port) can be at the end (or beginning) of a long dinner.

Although many of the wines of giant spumante houses such as Gancia, Cinzano, and Martini & Rossi are perfectly serviceable, the more interesting wines are to be found on a slightly (or much) smaller scale. The American-owned Villa Banfi winery in Piedmont—no slouch itself when it comes to pumping out bottles—makes solid, crisp Asti Spumante, as does the Giuseppe Contratto estate in Canelli (Contratto also makes dry, Champagne-style sparklers from chardonnay and pinot noir). The Fontanafredda winery in Serralunga d’Alba, better know for Barolo, also dabbles in spumanti. In the high altitudes of the classic moscato vineyards southeast of Asti, in tiny communes such as Neviglie, Canelli, and Santo Stefano Belbo, the moscato grapes are not only high in natural sugars but high in acidity as well, and the better spumanti are evidence of this: They have an almost spicy, citrusy character to complement their sweetness.

Although large houses dominate production, there are a multitude of smaller artisanal producers of both Asti and Moscato d’Asti. They include Walter Bera, Cascina Fonda, and Paolo Saracco, all of whom make the more softly contoured Moscato d’Asti as well. Other great Moscato d’Asti wines are made by Michele Chiarlo, whose “Nívole” bottling is one of the best, and the Forteto della Luja estate in Loazzolo, which bottles the full array of Piedmontese spumanti e dolci (see more on sweet wines).

With its relatively cool continental climate, Piedmont is able to produce good dry sparkling wines, many of them based on pinot noir and chardonnay (as is Champagne). The limestone-rich soils and high altitudes of the Langhe hills have inspired many Barolo and Barbaresco makers to plant chardonnay for both dry and sparkling wines; the grape often takes on a crisp, minerally character reminiscent of the chardonnay of Burgundy. But given the high labor and equipment costs of making sparkling wines, spumante is not a widespread product. Nevertheless, there are some méthode champenoise sparklers from the Langhe well worth checking out. One of the best is “Brut Zero,” made at the Rocche dei Manzoni estate, in Monforte d’Alba. Another good one is the Bryno Giacosa Brut, made at the legendary Giacosa winery from 100 percent pinot noir.

Lesser-known but equally interesting are the handful of spumanti made in the far-flung white-wine DOCs of Gavi, in the southeastern corner of Piedmont, and Caluso, in the north, near the border with Valle d’Aosta. The erbaluce grape of Caluso has the requisite sharp acidity to make fine, fragrant sparklers, as does the cortese grape of Gavi. In each zone, spumante takes a backseat to still wines made from these grapes, but the sparklers of producers such as Ferrando in Caluso and La Scolca in Gavi are surprisingly good and relatively affordable.

The name Piedmont means “foot of the mountain,” yet despite its northerly positioning and mountainous borders (ringed by the Alps and Apennines) it is still oriented much more to red wines than whites. Like many of Italy’s other northern regions, Piedmont’s wine traditions challenge conventional wisdom. It would seem given Piedmont’s position in the shadow of the Alps, and its relatively cool, often damp climate, that it might be better suited to white wine production. Nevertheless, between 60 and 70 percent of all Piedmontese wine is red.

It’s often noted that the Piedmontese town of Alba sits at a latitude similar to the city of Bordeaux, but you can’t really compare zones such as Barbaresco and Barolo with, for example, St. Emilión. Only the white-wine zone of Gavi, in Piedmont’s extreme southeast corner, receives any kind of Bordeaux-like maritime influence, from Mediterranean breezes blowing up through Liguria. Otherwise, viticultural Piedmont has a classic continental climate, which means that temperatures drop quickly in autumn, making things dicey for later-ripening red grapes.

It’s more accurate to compare Piedmont to Burgundy. The relatively cool climate may be more naturally suited to making white wine, but certain red grapes, planted in the right spots, can do amazing things. Piedmont’s focus on reds has historically been greater than Burgundy’s, but in recent times a handful of white grapes, including Burgundy’s chardonnay, have attracted their own fans.

Even in Piedmont’s northerly DOC zones—the ones that run along the border with Valle d’Aosta and follow the contours of the Alps toward Lake Maggiore—white wines get short shrift. There are more than a dozen wine zones in these Alpine foothills, and yet only one of them—Caluso, north of Turin—is dedicated to white wines. In a glacial basin around the towns of Caluso and Canavese, the erbaluce grape is made by a handful of producers into a chalky, searingly acidic dry white, as well as spumante and some excellent passito sweet wines. A number of these wines are exported, including dry whites from the Ferrando and Orsolani estates, which are marked by delicate floral aromas and the sharp, minerally tingle of mountain spring water. Generally speaking, the passiti from Erbaluce are more sought-after, but the dry whites are refreshing at a minimum, and well suited to a plate of prosciutto or bresaola drizzled with olive oil. Some experts compare Erbaluce to France’s chenin blanc, noting how it retains its refreshing acidity even when it is vinified sweet.

As lilting and floral as erbaluce, but more substantially fruity on the palate, the arneis grape has risen from relative obscurity to become what some people consider the most interesting white in Piedmont. Its principal area of production is the thickly forested Roero zone west of Alba, where it was traditionally interspersed with the more prevalent red nebbiolo. Sometimes it was blended with red grapes to soften them, but more often it was used to keep birds and bees away from the reds. Only in the late seventies and early eighties did vintners start making significant amounts of wine from arneis, following the lead of pioneers such as Ceretto (whose Blangé estate in Roero is still a top arneis producer) and Bruno Giacosa. While the grape is now popping up in other parts of the Langhe, the sandier soils of the Roero seem to be its preferred habitat—in fact, from 1989 to 1998, production of Roero Arneis DOC wine has more than quadrupled, with vineyard plantings surging from three hundred acres to more than one thousand. It’s notable that the 2005 elevation of Roero to DOCG status marks the first time a single DOCG incorparates both a white and a red wine.

The aromas of arneis are generally more fruit-driven than those of the herbal erbaluce, with scents of white grapefruit and sour apple mingling with those of white flowers. There’s also a smokiness to arneis that brings to mind the fiano of Campania, but arneis is more fruity than savory, and is more full-flavored. In addition to Ceretto’s “Blangé,” which is still a benchmark, look for arneis from Cascina Ca’ Rossa, Matteo Correggia, Monchiero Carbone, and Vietti, among many others.

One of the anchor towns of the Gavi DOCG zone (also called Cortese di Gavi) is the commune of Novi Ligure, which suggests an allegiance to somewhere other than Piedmont. In fact, the territory now known as Gavi was once a part of the city-state of Genoa, and is still profoundly influenced by neighboring Liguria. As noted above, the climate in the Gavi zone is nearly Mediterranean, but the chosen local grape, cortese, isn’t designed to take advantage of these more temperate conditions. It is one of a number of Italian whites that ripens stubbornly and unevenly, and its aromas are fairly mild, like those of garganega in Soave or trebbiano in Tuscany.

The soils in the Gavi zone, which includes the commune of Gavi itself almost smack in the center, are limestone-rich clays, generally whiter and chalkier-looking than the similarly limestone-rich soils of Langhe to the west. The classic style of Gavi, as popularized by producers such as Banfi Vini (with their “Principessa Gavia”) and La Scolca, directly reflects the wine’s origins: There’s a chalky minerality on the palate that some producers say is similar to some white Burgundy. That is a bit of a stretch, but then there tend to be very wide ranges in the style and quality of Gavi. Like Soave, to which it might be better compared, it is a light, refreshing white that became extremely popular in export markets (especially Germany and the United States), which in turn spurred the rise of large-scale, industrial producers and lots of watery wine.

For all of its commercial success, the Gavi region—like Soave again—isn’t a place people can readily conjure in their minds. There is very little tourism in the zone, leaving its multitude of smaller producers to eke out a living on the fringes. But there are many good wineries coaxing more concentrated apple and peach flavors out of the reticent cortese grape, including Broglia, Castelari Bergaglio, Castello di Tassarolo, and Michele Chiarlo. But the one producer really trying to make Gavi hot again is Villa Sparina, whose wild-man proprietor, Stefano Moccagatta, has been turning a part of his family’s estate into a Relais & Château hotel and restaurant. The Villa Sparina Gavis are more rich and extracted than most of their peers’—leading to speculation about what grapes aside from cortese might be blended in—and Moccagatta’s winemaker, Beppe Caviola, has experimented with fermenting and aging cortese in wood. But while the barrel-fermented Villa Sparina Gavi “Monterotondo” gets a lot of press, it is very tropical, fat, and somewhat atypical. Gavi is usually a wine of freshness and simplicity, which may not be fashionable but is often pleasurable. For some reason, simple has become a dirty word in Italian wine, even as the simplicity of Italian cooking is praised up and down. Maybe when people come around, so too will the fortunes of Gavi.

Of course, a region that likes to compare itself to Burgundy would not be complete without chardonnay. To its credit, Piedmont typically produces what might be called a Burgundian style of chardonnay. Most of the region’s chardonnay vineyards are located in the Langhe DOC zone, which includes within its boundaries both the Barbaresco and Barolo DOCGs, plus a broader swath of hills east and west of the Tanaro River. Created in 1994, the Langhe appellation is a catchall for producers in Barolo, Barbaresco, and beyond, enabling them to make wines from nebbiolo, for example, under less restrictive guidelines than those of Barolo or Barbaresco. The Langhe DOC includes provisions for a number of varietal wines, white and red, but the one that sticks out is chardonnay—mainly because it is the only non-native variety on the list.

In the calcareous clays of the Langhe hills, often on slopes not suitable for nebbiolo, chardonnay retains its acidity and minerality, whereas in many other areas farther south its sweeter, tropical-fruit side comes through. The same producers who looked to France for inspiration for their Barolos are doing the same with chardonnays, fermenting them in barriques to lend them a smoky, creamy complexity. To name just a few of a growing group, the Langhe chardonnays of Pio Cesare (“Piodilei”), Angelo Gaja (“Gaia & Rey”), Aldo Conterno (“Bussiador”), and Paolo Saracco (“Bianch del Luv”) have carved their own niches in a wine market inundated with the variety. In fact, Langhe Chardonnay may now be the biggest white-wine category in Piedmont, with countless producers making rich, complex, well-structured versions. Trendy as they may sound, these wines are not gimmicky: The better ones reflect where they come from in a very direct way.

Pio Boffa, the affable, fourth-generation proprietor of the Pio Cesare winery in Alba, says that confronting the intricacies of Piedmontese reds requires not just patience but humility. “Socrates said that the first step to knowledge is to admit that we don’t know anything,” Boffa says. Nowhere in Italian winemaking is this more apropos than in Piedmont. In the zones of Barbaresco and Barolo in particular, where the wavy landscape is portioned and parceled according to each slope’s particular relationship to the sun, the wines have been discussed and debated so thoroughly that it is hard to know where to begin. Most people tend to wax poetic, remarking on the ethereal aromas of a well-aged Barolo as if they were describing a religious experience, while others are all about science: the soil compositions of the myriad vineyard sites, their relative exposures to the sun, and of course the tricks of the trade used in the winery. The discussion and debate is ongoing, leading to subtle (and not-so-subtle) changes in the wines with each new vintage.

Looking at the big picture, Piedmontese reds don’t seem overly complicated. In the DOC zones north of the Po, there’s an almost unbroken chain of wines made principally from the nebbiolo grape—Carema, Canavese, Gattinara, and Ghemme, among others. Typically, these wines tame the high acidity and occasionally ragged tannins of northern-limits nebbiolo (here called spanna) with softer, fruitier local varieties such as bonarda and vespolina, which comprise 40 percent (or more) of certain DOC blends. Among this group, the purest expressions of nebbiolo are Gattinara and Ghemme—two of Piedmont’s seven DOCG zones—which at times can be as powerful, concentrated, and aromatic as the Barolos and Barbarescos made farther south.

South of the Po, nebbiolo shares the Langhe and Monferrato hills with the plump and purple dolcetto grape and the super-prolific barbera, along with a smattering of lesser-known varieties such as freisa, grignolino, and ruché. That sounds easy enough, too, until you consider the tangle of DOCs in the southeast. There are three “grape-specific” DOCs for barbera and a whopping seven for dolcetto, even though few people aside from the producers themselves could hope to sort out the differences between Dolcetto d’Acqui, for example, and Dolcetto d’Asti.

And yet, for all of the different choices, there’s a logic to Piedmont’s reds that contrasts with the often scattergun approach to wine in many other Italian regions. However much they might vary in character within their respective families, the three principal red grapes—barbera, dolcetto, and nebbiolo—are distinct entities. Together they fit together like pieces in a puzzle: barbera and dolcetto make the more readily accessible, “fun” wines, the ones to drink while the more brooding nebbiolo ages. And each of the three has characteristics that the other two lack, allowing for a variety of balanced and intriguing blends. In dolcetto, you get soft tannins and plump, grapey fruit. In barbera, you get bright acidity and a more sour, spicy red fruit character. And in nebbiolo, you get tar and leather and spice. Where dolcetto and barbera are ripe and ready, nebbiolo is more about complexities revealed over time. That’s Piedmont in a nutshell: so many wines, so little time.

Thought to be native to the Monferrato hills, near Asti and Alessandria, barbera is equally at home on the slopes of the Langhe, near Alba. Aside from the DOCs of Barbera d’Asti, Barbera d’Alba, and Barbera del Monferrato, the grape factors into other lesser-known appellations, such as the Rubino, Gabiano, and Colli Tortonesi wines of the extreme southeast. Barbera is the most heavily planted red grape in Piedmont, accounting for more than 50 percent of DOC red wine production in the region. Without a doubt, it is the most adaptable and vigorous of Piedmont’s three main red grapes, a fact that has led to an almost impossibly broad range of styles. Even within its specific DOC zones, barbera tends to vary widely, from bright and cherry-scented, firmly acidic, and a little rustic to more rich, robust, and silky smooth. A lot of this depends on where its growers choose to plant it, but it is also the product of changing winemaking practices. Of course, this is true of any wine, and barbera is an interesting case study in how a wine grape reacts to different soils, climates, and techniques.

Barbera’s constants are a high level of natural acidity and a relatively low level of tannin, although the grape generally produces wines of a deep ruby color. The variables are the levels of fruit extraction in the wine, and the degrees to which tannins have been added through aging in oak barrels. “If you taste a tannic barbera,” says Bruno Ceretto, coproprietor of the Ceretto estate in Alba, “it’s because the winemaker has either used a lot of new oak or is blending it with some other more tannic variety. Barbera on its own gets a bite from acidity, but it doesn’t have tannin.”

Among the first producers to address this was the late, legendary Giacomo Bologna. His estate in the Asti DOC zone, called Braida, was among the first to create barbera wines that had not only been planted in choice vineyard sites—to increase their concentration of red-cherry flavor—but had been aged in French oak barriques, which lent the wood’s tannins to the wine. When Bologna’s “Bricco dell’Uccellone” Barbera was released in the early eighties, its then-uncommon richness and seeming ageability sparked a wave of experimentation with the grape that continues today.

In the past, especially in the hills of the Langhe, the durable and easy-to-grow barbera was often used used as “filler” in vineyard sites incapable of maturing the more stubborn, weaker, and later-ripening nebbiolo. So it was often only natural that barbera wines were relatively light, acidic, and even a little rough around the edges. These days, the average barbera is considerably more colorful and plush, its character leaning more toward red fruits (cherries, currants, raspberries), at least when it hasn’t seen a lot of time in oak barrels. But since there is such a wide variety of barbera produced, it is extremely difficult to generalize about the category. Beyond that, it’s a question of scale, and, as might be expected, the hottest-selling barberas these days are the larger-scale versions.

One way to sort through the barbera style spectrum is to start with what might be called “baseline” bottlings—namely, those that say simply Barbera d’Alba, Barbera d’Asti, or Barbera del Monferrato. These are likely to be the simpler, leaner, more acidic styles emphasizing fresh red-fruit flavors, as most producers typically offer a vino fresco (fresh wine, one that is bottled soon after the vintage, for immediate sale). As an introduction to barbera, pick up a simple Barbera d’Alba or d’Asti from a Barolo or Barbaresco house such as Pio Cesare, Bovio, Bartolo Mascarello, Vietti, or Renato Ratti (to name a few among the hundreds). You’ll find these wines to be slightly rustic, with a sharp tingle of acidity that needs a little food to tame it. The flavors are likely to be more reminiscent of dried cherries, with a touch of earthiness, whereas those wines carrying a vineyard designation (like “Bricco dell’Uccellone”) or a nome di fantasia (fantasy name) will be more densely fruity and, most especially, toasty and rich from time spent in oak barrels. For examples of a denser, more extracted style of barbera, look to producers such as Hilberg Pasquero, Aldo Conterno, Prunotto, and Michele Chiarlo, whose “La Court” is a good example of the depth barbera takes on when it is aged in barrique.

Probably the most notable feature of “modern” barbera is the weight of fruit extract it exhibits on the palate. Whereas barbera was little more than filler in the past, vintners have found that it grows into a densely concentrated wine when grown in choice south-facing sites. As a general rule, today’s barbera is much bigger than the barbera of the past.

Of the three main barbera DOCs, those of Alba and Asti are expansive, with Monferrato bringing up the rear. In Monferrato, which is situated to the east of Asti, producers to look for include Villa Sparina (which makes some dense, superextracted reds to go with its Gavis), Giulio Accornero, Scrimaglio, and Vicara. But in Alba and Asti, the list of noteworthy names is almost as long as that for Barolo and Barbaresco, near which the Barbera of d’Alba and Barbera d’Asti DOCs are situated. Most Barolo and Barbaresco producers make at least one version of Barbera d’Alba and/or Asti and often several, many of which are single-vineyard wines with the structure (and price tags) to stand up to some Barolo.

Like barbera, the dolcetto grape, whose name means “little sweet one,” is highly permeable. As the earliest-ripening of the three main Piedmontese reds, it is often planted in sites where even barbera might not become fully ripe. It distinguishes itself from both barbera and nebbiolo with its deep purple-violet color, its low acidity (making it a good blending partner for both of the others), and its full yet sweet tannins. Dolcetto is the most gregarious, forwardly fruity wine of the bunch, and is usually drunk young. But many producers see it as something more.

Dolcetto wines are produced under seven different DOC classifications, among them d’Alba, d’Asti, di Diano d’Alba, d’Acqui, and delle Langhe Monregalesi. There are excellent wines from each of these areas, of course, but all of these DOCs overlap with several others, from Moscato d’Asti to Brachetto d’Acqui. When you see Dolcetto d’Alba, it’s not as if dolcetto is the only grape planted there—rather, the grape shares space with a host of others, including barbera. Two zones considered more specialized in dolcetto are the Dolcetto di Ovada DOC (in the extreme southeast near Gavi) and the Dolcetto di Dogliani DOC (south of Alba). The dolcetto grape is believed to have been discovered in the commune of Dogliani, where references to the grape can be traced back to the fifteenth century. Modern-day producers in Dogliani believe that theirs is not only the original dolcetto, but also the richest and most flavorful, and there is considerable experimentation being done with the grape in that zone to turn it into a full-blown international red. Equally interesting is Ovada, another historic territory for the grape, where dolcetto takes on a more rustic, full-bodied character than in many of the other zones.

With aromas of violets and black fruits, and usually a tinge of licorice and even coffee on the palate, dolcetto might best be described as part of a vinous color scheme. Barbera and nebbiolo tend to produce more “red” red wines—with flavors of fresh and dried cherries, red raspberries, and then a variety of earthy, spicy, leathery notes. But the dolcetto grape is more a purple or black wine, as evidenced not only by its deep color (something nebbiolo in particular lacks) but its black-fruit flavors. It is the juiciest and fruitiest of the Piedmont reds; the more full-bodied, barrel-aged versions taste like a spread of blackberry jam on toast.

Depending on the level of extraction a producer goes for in his dolcetto—a function not only of viticulture but the length of time the wine spends on its skins during fermentation—the wine may be light, soft, and almost Beaujolais-like in character, or plumper, rounder, with silty-sweet tannins and a sappiness reminiscent of California merlot. Given the success of wines styled in the latter fashion—such as those of Beppe Caviola in Alba, or of the tight-knit crew of wineries in Dogliani (including Abbona, Pecchenino, Quinto Chionetti, and San Romano)—dolcetto is being held up as the new-generation wine of Piedmont.

“Because of the low acids, it is accessible when it is young,” says Tino Colla, owner of the Poderi Colla estate in Alba. “But dolcetto is very sneaky. Its tannins are sweet, but they are abundant. When you tack on some time in oak barrels, you have a wine with the ability to be aged. But of course the overwhelming preference of the market today is for wines that can be drunk in their youth. Dolcetto is our answer to that.”

Colla makes a Langhe DOC–classified blend called “Bricco del Drago,” combining 85 percent dolcetto and 15 percent nebbiolo, a wine that distinctively demonstrates how Piedmont’s reds complement and contrast one another. Whether on its own or as part of a blend, dolcetto is a generous variety. “Dolcetto has incredible roundness, but it doesn’t really have focus,” Colla explains. “Nebbiolo, of course, has focus.”

The nebbiolo grape, and the wines made from it in the zones of Barbaresco and Barolo, have been subjected to more scrutiny than any other wines in Italy. This is partly the fault of the producers, who are not only numerous but generally a contemplative lot. Centuries ago, farmer-winemakers examined the rolling hills to see where the winter snow melted first, deducing that these were the sites that received the most sunlight and therefore the most appropriate places to plant vines. Viticulture in the Langhe is all about subtle variations in altitude, exposure to the sun, and soil composition, and it seems as if every ripple in the earth around Alba and Asti has been studied and charted. Often, vintners own chunks of more than one slope, and when it comes time to bottle their wines they have distinct brands determined not by the whim of the winemaker but by the whims of nature.

This is the romantic view, of course. But what is wine without a little romance? For someone who loves wine, there may be no more heady experience than winding through the hills of Barolo and Barbaresco, through medieval villages such as Neive (in Barbaresco) and Castiglione Falletto (in Barolo), marveling at the rows of vineyards snaking like braids over every available slope. At every curve in the road is a sign for a wine estate, ranging in size from garage to sprawling compound. Restaurants are filled with the pungent scents of truffles or wild mushroom risottos, golden Toma cheeses, all sorts of chestnut and hazelnut torte. The rich food of Piedmont is best described as forestale (foresty), and in Barolo and Barbaresco they have wines to match, with assertive scents of cedar and wild mushrooms and earth.

The land of nebbiolo south of the Po is a broad swath of hills around the Tanaro River, which runs through the towns of Alba and Asti before hooking up with the Po near Alessandria. The key DOC zones along this route are Barolo, southwest of Alba; Roero, on the left bank of the Tanaro west of Alba; and Barbaresco, northeast of Alba. In this relatively small space are a wide array of producers, without a doubt the densest concentration of winemaking activity in Italy.

Nebbiolo is often described as one of Italy’s noble varieties. It is known first and foremost for being fiercely tannic, and yet those gripping tannins are extracted from very thin skins that don’t hold a lot of coloring pigments. Many Barolos, Barbarescos, and Roero reds, especially those that have begun to take on a characteristically orangey cast with age, look in the glass to be relatively light wines. But even well-aged ones grab the tongue with those tannins, and explode across the palate with an array of flavors that taxes the imaginations of even the most flowery wine writers. Because of their tannic grip and fairly high levels of alcohol, Barolos and Barbarescos are often described as heavy wines. And they certainly can be. But the mark of a good Barolo is not its weight on the palate but the penetrating, perfumy aromas of the nebbiolo grape. Like sangiovese in Tuscany and aglianico in Campania and Basilicata, nebbiolo is one of those grapes with fairly precise aromatic indicators: The fruit component is of dried cherries and other dried red fruits, with other scents ranging from wild roses to truffles to cinnamon, lending the wine complexity. These aren’t fruity, jammy wines. They are wines with a balance of sweet, savory, and spicy elements that tingle on the palate, their aromas like vapors that waft up into your brain and lodge themselves in your memory forever.

Is that a little too much? Well, probably. But this is what nebbiolo does to people. Although it’s difficult to grow and extremely late-ripening, its producers are willing to wait until late October and November to harvest it, despite the ever-looming threat of rain after September. The variety is said to be derived from the word nebbia, Italian for “fog,” presumably in reference to the dense blankets of the stuff that roll into the Langhe every fall, cooling the vines with their mists and allowing the grapes to hang on the vine that much longer to develop more complex aromas and flavors.

Nebbiolo drinkers, too, are willing to wait. It was traditionally said that both Barolo and Barbaresco needed to age some two decades before being “ready to drink.” According to the production disciplines of their DOCGs, Barbaresco and Barolo must be aged several years before they are even released. In Barbaresco, where the slightly cooler climate is said to produce slightly finer versions of nebbiolo, the minimum aging is two years (one of which must be spent in oak or chestnut barrels); in Barolo, the minimum aging is three years, two of them in barrels. And for riserva wines, the totals go up to four and five years of total aging, respectively. Usually, these aging periods start at the beginning of the year following the vintage, meaning that a vintage 2000 Barolo, for example, would be released three years after 2001, or 2004. Wines made under the Nebbiolo d’Alba and Langhe DOC classifications are subject to less stringent geographic and technical requirements, which allows producers to make softer, more readily accessible nebbiolos and blends (usually with barbera and/or dolcetto) to complement their more burly Barolos or Barbarescos.

Although wine has been made in Piedmont since ancient times, viticulture in the region was heavily influenced by the French, when Piedmont was part of the House of Savoy, from the early eighteenth century to the time of the Italian unification in 1861. Barolo in particular is referred to as the “king of wines and the wine of kings,” since the earliest dry red wines from the Barolo area were developed by noble families from Turin and the ruling Savoyards. Most sources attribute the creation of Barolo to Giulietta Falletti, the marchioness of the village of Barolo, who in the early 1800s developed a Bordeaux-style wine from nebbiolo with the help of French enologist Louis Oudart. Oudart had been summoned to the Alba area in the first place by Camillo Benso di Cavour, a local count who not only became the prime minister of Piedmont but one of the leaders of the movement for Italian unification. Another noteworthy noble who helped shape the Barolo zone was Vittorio Emanuele II, the first king of unified Italy, whose son Emanuele (borne by a royal mistress named Rosa Vercellana) planted vines around a family refuge called Fontanafredda, near Serralunga d’Alba. (Fontanafredda is still one of the best-known names in the Barolo DOCG, and one of its largest contiguous properties).

Although they were not known for Barolo or Barbaresco, large commercial wine houses such as Martini & Rossi and Gancia were formed in the late nineteenth century, to be followed by numerous others at the turn of the twentieth. More so than other regions, Piedmont was not just a culture of myriad individual contadini (farmers) but actually had a wine “industry” to speak of well before the First World War. Although it went through much of the same upheaval as the rest of Italy during the fifties and sixties, with families abandoning the countryside in search of work in the cities, winemaking remained firmly rooted in places like Alba and Asti. Today there are a number of wine houses—including Barolo makers such as Borgogno and Pio Cesare—whose strings of vintages date back more than a hundred years, interrupted only by the two World Wars.

Barolo and Barbaresco offer a lifetime’s worth of study for those wine drinkers obsessed with comparison and contrast. Although the soils in both zones are predominantly limestone-rich marls (marl is a cool, crumbly clay that helps to slow ripening and to build acidity), and the altitudes in the zones relatively uniform (usually between four hundred and twelve hundred feet), the subtle differences imparted by these and other natural factors are what Barolo and Barbaresco are all about. Strange-sounding names such as “Sorì San Lorenzo,” “Rabajà,” “Cannubi,” and “Brunate” are emblazoned across the labels, inviting the curiosity of the uninitiated. They are vineyard names, carrying with them all sorts of cryptic information: If you know that Cannubi, for example, is a low-lying slope just outside the town of Barolo, with a southeastern exposure that gives it full access to the morning sun (which is said to impart to the wines a certain power but a less aromatic personality), then “Cannubi” might mean something to you. But to get to that point is to reach the pinnacle of wine geekdom—a point at which you’ve thrown over nearly everything else in your life in order to search for subtle differences that are usually obscured by the varying techniques winemakers use once they get their Cannubi or Brunate grapes into the cellar. For more on the highly variable personality of the great wines of Barolo and Barbaresco, see the preceding boxes on vineyard designations and style. But be warned: This is only the beginning of what can easily become an all-consuming and expensive hobby.

Reaching toward the lake district of northern Lombardy, with Milan not far to the east, the nebbiolo DOCs of northern Piedmont are home to some hidden gems. These regions have generally poorer, grittier soils of glacial moraine, and breezes from the Alps sweep through from the north. Here in Carema, Gattinara, Ghemme, and other north-of-the-Po DOCs, nebbiolo struggles even more mightily than it does elsewhere to get fully ripe. So these wines are typically more delicate and higher in acid than their Langhe counterparts, and only in exceptionally hot and dry vintage years (’97 was an especially good one, as was ’99) will they approach the power of Barolo or Barbaresco.

Because nebbiolo here is higher in acidity and occasionally gruffer in personality than even Barolo, it requires a little blend. Yet there are some incredible finds within these DOCs, most of them wines that showcase the perfumy side of the nebbiolo grape. From Carema, look for the wines of Luigi Ferrando and the local co-op, Cantina Produttori Nebbiolo, for an especially aromatic take on nebbiolo. From Gattinara, a little farther east, producers such as Nervi, Travaglini, Dessilani, and Antoniolo are making deeply aromatic nebbiolo to compete with Barolo. Gattinara, a DOCG, represents the purest expression of nebbiolo of the northern zones. And in Ghemme, the wines of the Cantalupo estate strike a balance between delicate and dense.

Moving back down to the Langhe, the wines of Roero merit another mention, not least because the appellation was recently elevated to DOCG status. As noted earlier in these pages, a DOCG is really no guarantee of anything, but in the case of Roero, which is comprised of 95 to 98 percent nebbiolo, there is a tremendous amount of excellent wine that doesn’t get the recognition it deserves. With each vintage, producers such as Cascina Ca’Rossa, Malvirà, Angelo Negro, and Matteo Correggia release Roero wines with all of the smoky intensity and structure of great Barolo. Maybe the flashy new DOCG will help attract more attention to this overlooked area.

After all that dolcetto, barbera, and nebbiolo, Piedmont is loaded with a wide variety of other oddities, many of which are surprisingly likely to turn up on American wine lists or in shops. The rarest is a light red called grignolino, produced in small quantities in the Monferrato hills, which produces very light, almost rosato wines with a spicy tang and orangey color. Another local red is freisa d’Asti, a uniquely flavorful variety that is made in both dry, sweet, and frizzante styles, sort of Piedmont’s answer to Lambrusco. The same goes for ruché, another curiosity with a distinctive berryish aroma, whose main claim to fame is that it will grow in spots where even barbera won’t mature. These wines are easily classified as “farmhouse” reds, the wines to drink when winding through the hills of Piedmont on a tour of the vineyards. Take a break from serious Barolo sniffing to sip a lightly chilled freisa or ruché alongside a plate of prosciutto: You may be surprised how much you like it.

BAROLO

• La Morra. In the northwestern sector of the Barolo DOCG, this commune includes, among others, the Arborina, Marcenasco, Monfalletto, Cerequio, and Brunate vineyards (the latter two are shared with the commune of Barolo). These vineyards typically produce especially aromatic, perfumed Barolos, as evidenced by the wines of Elio Altare (whose most famous Barolo is from the Arborina cru), Renato Ratti (Rocche dell’Annunziata), Gianfranco Bovio (Arborina), Marcarini (Brunate), and Michele Chiarlo (Cerequio). Probably the most famous La Morra producer these days is Roberto Voerzio, who is one of the more outspoken modernists in the zone, and whose wines tend to be especially powerful. His wine from the Brunate cru is the best evidence of this—although Brunate is a directly south-facing site, and one from which many other producers are making denser-than-average wines.

• Barolo. Some of the broadest, most open vineyard sites are located within the commune of Barolo, resulting in some of the broadest, most open, and most youthful Barolos available. The best-known cru in the commune is Cannubi, known for plush and warm Barolos from producers including Luciano Sandrone, Paolo Scavino, Marchesi di Barolo, and Prunotto. Other choice sites in Barolo include Sarmassa and the Barolo part of Brunate.

• Castiglione Falletto. Although it is technically on the eastern side of the Barolo zone, the commune of Castiglione lies near the geographic center of the appellation. Stylistically, the wines occupy a middle ground between the ethereal, perfumed wines of La Morra to the west and the dense, tannic wines of Serralunga and Monforte to the southeast. Prized vineyards in Castiglione include Rocche (top producers from this site include Vietti and Aurelio Settimo), Momprivato or Monprivato (Brovia, Giuseppe Mascarello), and Villero (Bruno Giacosa, Vietti, Brovia, Giuseppe Mascarello).

• Serralunga d’Alba. Here at the eastern edge of the Barolo DOCG the wines gain added depth and concentration from soils which are richer in sandstone, creating more deeply extracted and tannic Barolos. Key vineyard sites include Lazzarito (Fontanafredda), Vigna Rionda (Giacosa, Oddero), Prapò (Mauro Sebaste), Ornato (Pio Cesare), and Monfortino (the famed vineyard of the Giacomo Conterno winery, which produces one of the longest-lived Barolo wines ever made).

• Monforte d’Alba. The vineyards that lie between the town of Monforte d’Alba and its neighbor due north, Castiglione Falletto, may be the best in all Barolo. Many of the most celebrated Barolo producers are located here, and they may be so celebrated because of the vineyard sites that also lie within the commune. Big and bold, dark and rich, Monforte Barolos are characterized by crus such as Bussia (Aldo Conterno is the most famous interpreter, but there’s also Armando Parusso, Prunotto, Poderi Colla, and many others), Ginestra (Domenico Clerico, Elio Grasso), and Santo Stefano di Perno (Rocche dei Manzoni).

• Barbaresco: Most of the better-known Barbaresco crus lie within the commune of Barbaresco itself, especially along a south-southwest-facing ridge that runs along the road from Barbaresco south toward Treiso. This ridge includes the aforementioned Secondine cru, along with Pajé (whose best-known producer is Roagna-I Paglieri), Asili (Ceretto most famously, but also Michele Chiarlo and Ca’ del Baio), Martinenga (Marchese di Gresy), and Rabajà (Bruno Rocca, Cascina Luisin). Due east of the village of Barbaresco is the south-facing Montestefano cru, made famous by the legendary co-op Produttori del Barbaresco. As always, it is difficult to generalize, but Barbarescos of the commune of Barbaresco tend to be among the fruitiest and most generous, especially wines from crus such as Asili and its neighbor to the west, Faset, which face directly south, thereby taking in the sun all day long.

• Neive: The northeastern chunk of the Barbaresco DOCG is characterized by a typically leaner, more austere style of wine. The village of Neive sits at the highest altitude of any of the Barbaresco communes and its higher-altitude vineyards tend to produce more perfumed grapes with firmer tannic structures. Key Neive vineyard sites include Basarin (Moccagatta makes the best-known wine from the site), Gallina (the supercharged bottling from La Spinetta is the most famous, if a little atypical), Starderi (also La Spinetta), and Serraboella (Cigliutti).

• Treiso: At the southern end of Barbaresco, Treiso’s crus are probably the least known, but there are some excellent wines. Probably the best-known, Treiso Barbaresco, is Pio Cesare’s firm and fine “Il Bricco,” sourced from the Treiso cru of the same name. Other key sites include Bernardot (Ceretto-Bricco Asili), and Nervo (Elvio Pertinace).

Because most (but not all) of Piedmont’s sweet wines are sparkling, and most (but not all) of its sparkling wines are sweet, it’s difficult to decide how to classify them. Asti is without a doubt a sweet wine, but it tends to be grouped among spumanti nonetheless. Meanwhile, the red Brachetto d’Aqui, which is most often made as a sparkling wine, is usually grouped among the dolci. Brachetto, another of Piedmont’s dry-or-sweet reds, has managed to climb all the way to DOCG status, in fact, at least in part because of the wine’s natural affinity with the great chocolate of Piedmont. Rose-scented, with delicate hints of strawberry on the palate, a good sweet brachetto—either still or sparkling—is a unique sweet-wine experience. Rather than being weighty or sappy on the palate, these wines have an appealing brightness that won’t weigh you down at the end of a meal. For a great example of a sweet-yet-still version, check out the brachetto from Forteto della Luja, an estate in Canelli known for a variety of dessert wines from both brachetto and moscato. The other noteworthy nectars of Piedmont are the passito wines made from the erbaluce grape in Caluso, best exemplified by the wines of Ferrando.

PROVINCES: Alessandria (AL), Asti (AT), Biella (BI), Cuneo (CN), Novara (NO), Vercelli (VC)

CAPITAL: Torino

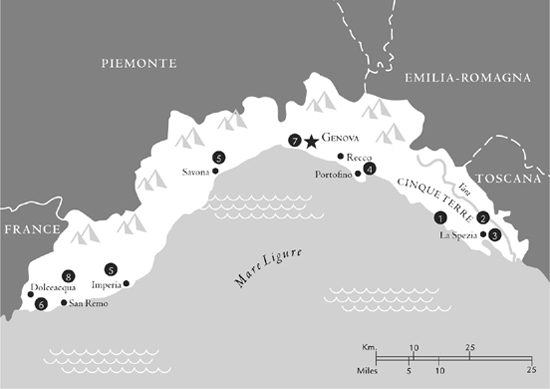

KEY WINE TOWNS: Alba, Asti, Barbaresco, Barolo, Castiglione Falletto, Gavi, La Morra, Monforte d’Alba, Neive, Serralunga d’Alba

TOTAL VINEYARD AREA*: 52,585 hectares, or 129,938 acres. Rank: 6th

TOTAL WINE PRODUCTION*: 2,938,000 hectoliters, or 77,621,960 gallons (7th); 68% red, 32% white

DOC WINE PRODUCED*: 61.3% (3rd)

SPECIALTY FOODS: hazelnuts; chestnuts; truffles; carne cruda (raw meat, usually veal, topped with oil, lemon, and often truffles); agnolotti del plin (small meat-filled pasta, often served with a brothlike sauce in Alba); bollito misto (mixed boiled meats, usually served with savory red and green dipping sauces); Bra (cow’s- and goat’s-milk cheese, often sharp); Toma (wide-ranging family of mostly cow’s-milk cheeses).

*2000 figures. Rankings out of 20 regions total (Trentino–Alto Adige counted as one). Source: Istituto Statistica Mercati Agro-Alimentari (ISMEA), Rome.

ARNEIS: Records of this grape date back to the 1400s in the Roero hills. It was traditionally used as a blending grape to soften red nebbiolo wines, but recent years have seen a surge in plantings. It produces fine, floral, citrusy whites.

CORTESE: Grapier, plumper, and less aromatic than arneis, it is the base of Gavi DOCG wines. Considered a native to the Monferrato hills.

ERBALUCE: Herbal, piercingly acidic variety grown in the northerly reaches of Piedmont near Valle d’Aosta, particularly the town of Caluso north of Turin. Makes crisp dry whites and sharp, fragrant sparklers, as well as passito sweet wines.

MOSCATO: The Piedmontese use the superior moscato bianco (muscat à petits grains in French), which has come to be known as moscato canelli, after the town of Canelli, not far from Asti. Used in the famed frizzante and spumante whites of the Asti DOCG.

OTHERS: CHARDONNAY, increasingly popular in the Langhe hills.

BARBERA: Piedmont’s most-planted red, considered a native of the Monferrato hills. Durable and extremely productive, it grows just about anywhere and is thus planted in just about every conceivable place—leading to wide variations in style.

BRACHETTO: A native red used for sweet wines, both still and sparkling.

DOLCETTO: The name means “little sweet one,” in reference to its sweet taste when ripe. Deeply colored but with soft tannins, the variety ripens early and produces soft, fruity, accessible reds with plush black fruit flavors. Increasingly, producers are creating denser wines from the variety by aging their wines in small oak barrels.

NEBBIOLO: Purportedly named for la nebbia (fog) that descends on the hills of Barolo and Barbaresco every fall, this is Italy’s answer to pinot noir. Considered native to Piedmont, records of its cultivation date back to the 1300s. Late-ripening and sensitive to adverse vintage conditions, it nevertheless produces Italy’s most uniquely perfumed and powerful red. Its skins are surprisingly thin for a grape known for its biting tannins, making it susceptible to breakage, and typically the color of Barolo leans more toward light ruby, even as a young wine.

OTHERS: FREISA and RUCHÉ, used in light, fruity reds; GRIGNOLINO, used to make rosé-style wines.

Every vintage is a nail-biter in Piedmont, where the late-ripening nebbiolo races with the weather each October and November on its journey to ripeness. Autumn in the hills of the Langhe is reliably damp and foggy, so not only is a hot, dry summer essential for full maturation of the grapes, but the autumn rains must hold off long enough for producers to pick grapes at the optimal level of maturity. Whereas the early-ripening dolcetto and the durable barbera are fairly consistent wines from vintage to vintage (both of these softly tannic varieties are meant to be consumed young, for the most part), the wines of Barolo and Barbaresco are another story. In cool or excessively damp years the wines are likely to be thin and harshly tannic, whereas a favorable vintage brings out incomparable flavors, textures, and aromas. Recent years have been very good to Piedmont, with 1995 through 2001 all producing excellent wines (the 2000 vintage received probably the greatest acclaim of all, but producers are even more enthusiastic about 2001); “For me, ’96 and ’01 were the best expressions of Piedmont,” says Domenico Clerico, a leading Barolo producer, who says that the years ’96 through ’01 were one of the most glorious runs Barolo has ever enjoyed. As in other parts of Italy, ’97, ’99, and ’00 were exceptionally hot, dry years, producing wines with more power and extract; ’96, ’98, and ’01, according to Clerico, were more climatically even, creating wines that were powerful in their own right but more aromatically expressive and balanced. Here’s a list of the best of the last two decades in Barolo and Barberesco: 1982, ’85, ’88, ’89, ’90, ’96, ’97, ’98, ’99, ’00, ’01, ’04.

The undulating hills around Alba and Asti are Mecca for the serious wine enthusiast. In fact, there isn’t much else to do in Alba and Asti but eat and drink. Of the two towns, Alba is more quaint and probably better as a base of operations for visiting the vineyards of Barolo and Barbaresco. Go in September or October, as the nebbiolo vines are reaching their full maturity and the weather is starting to turn cool, and just amble through one of the most striking stands of vineyards in the world. There’s an enoteca seemingly around every corner in the villages of the Barolo and Barbaresco DOCs, the best known being the Enoteca Regionale del Vino Barolo in—you guessed it—the medieval village of Barolo (Piazza Falletti; 0173-562-77). The Barbaresco zone has its own Enoteca Regionale in its own namesake village, and it, too, is an ideal place to sample local wines. As for restaurants, perhaps the ultimate destination for great Barolo, truffles, and Piedmont food is the Ristorante Guido, located in the Relais San Maurizio hotel in Santo Stefano Belbo (0141-84-19-00). In the heart of Alba is a known winemaker hangout called Osteria dell’Arco (Piazza Savona 5; 0173-36-39-74), while in the village of Barolo the Locanda nel Borgo Antico (Piazza Municipio 2; 0173-563-55) offers a similar sense of being one with the wine crowd. In La Morra, winemaker Gianfranco Bovio’s Belvedere (Piazza Castello 5; 0173-501-90) is one of the benchmark restaurants of the Barolo area; in Neive, in the heart of the Barbaresco DOCG, the landmark restaurant is La Contea (Piazza Cocito; 0173-671-26).

Bartolo Mascarello Dolcetto d’Alba, $–$$

Ca’ Viola Dolcetto d’Alba, $$

Chionetti Dolcetto di Dogliani “Briccolero,” $–$$

Here’s a good look at the style spectrum of dolcetto, from the earthier, more traditional wine of Bartolo Mascarello, with its brambly, spicy blackberry tones, to the plump and chunky wines of Chionetti and Ca’ Viola, two producers who strive for a greater level of extraction in their wines—the better to stand up to their aging in small oak barriques. While long thought of as Italy’s answer to Beaujolais, dolcetto has become a considerably more powerful, extracted red, as illustrated by the Ca’ Viola wine in particular. What’s noteworthy about all of these wines is how soft and accessible they are, and how deeply colorful. These are plump, “purple” wines for sipping with sausages, prosciutto, and other snacks, always ready to go on release. Other good dolcettos to seek out: Villa Sparina’s Dolcetto d’Acqui “D’Giusep”; the Dolcetto di Doglianis of Marzieno and Enrico Abbona; and the Dolcetto d’Alba of top Barolo and Barbaresco producers such as Luciano Sandrone, Roberto Voerzio, Paolo Scavino, Ceretto, and Giacomo Conterno—usually these wines tend to mirror the style of their respective house’s Barolo (i.e., if the Barolo is rich, extracted, and oak-influenced, chances are the dolcetto will be too, albeit at a much more agreeable price).

Vietti Barbera d’Alba “Tre Vigne,” $

Prunotto Barbera d’Alba “Pian Romualdo,” $$

Braida di Giacomo Bologna Barbera d’Asti “Bricco dell’ Uccellone,” $$$

Here are three benchmark barberas that demonstrate how variable the character of the grape (and the wine) can be. The Vietti wine, widely available and consistent from vintage to vintage, is a good place to start: Its aromas and flavors of red cherries are carried along on a wave of bright acidity, giving the wine a liveliness that is typical of more fresh (i.e., little or no wood aging) barberas. The Prunotto wine, also easy to find, is a little more deeply extracted than the Vietti, with slightly “blacker” fruit flavors, and there’s also a distinctly oakier note that lends the wine a deeper, more somber tone. And then there’s “Bricco dell’ Uccellone,” a legendary (and therefore rare and expensive) wine that should be tasted by anyone looking to gain a deeper understanding of barbera. The brightness and red fruit flavors of the Vietti wine are found in this bottling as well, as are the smoky, creamy oak notes of the Prunotto. Yet the hallmark of “Bricco dell’ Uccellone” is how well integrated those seemingly diverse elements are. This is a wine of serious structure that nevertheless retains a certain youthful exuberance. Like the others, it’s very versatile with food—try it with game birds or some of the lighter Piedmontese cheeses.

Poderi Colla “Bricco del Drago,” $$

Rocche dei Manzoni “Bricco Manzoni,” $$

Conterno Fantino “Monprà,” $$$

This flight is all about the interplay of Piedmont’s “big three” of red grapes: nebbiolo, barbera, and dolcetto. The Poderi Colla wine was one of the first commercial blends of dolcetto and nebbiolo, and in tasting the wine you get a clear sense of what each grape brings to the table: The inky color and jammy fruit come from the dolcetto, while the firm structure and hint of dried-fruit aroma come from the nebbiolo. In Rocche dei Manzoni’s “Bricco Manzoni” it’s barbera, rather than dolcetto, that’s used as the softening agent for the angular, aromatic nebbiolo. This wine has a slightly more savory profile, with notes of woodsy red cherry and a hint of cinnamon, essentially a Barolo flavor profile but a barbera “feel” on the palate. Finally, there’s “Monprà,” which combines nebbiolo, barbera, and cabernet sauvignon. This is the densest and most extracted of the group, layering the ripe, sweet fruit flavors of barbera and cabernet over a tannic, savory base of nebbiolo. It’s a deep, rich wine for steaks or stews.

Produttori del Barbaresco Barbaresco Torre, $$

Moccagatta Barbaresco, $$$

Gaja Barbaresco, $$$

It’s often said that Barolo is the king of wines, and Barbaresco the queen. In tasting through these base-level bottlings from three famous producers, you may detect a certain femininity in the wines: They all have heady perfumes of dried cherries, tea leaves, cinnamon, and other elements both sweet and savory, while on the palate they are full-flavored and tannic yet fine and focused. Barbaresco is rarely a sappy, juicy wine: It is firm, angular, and tightly coiled, particularly as a young wine (we assume you’ll be comparing current vintages of these). Barbaresco seems almost nervous on the palate, and as a young wine needs some weighty, fatty food to counter its tannic bite and bring out the fruit flavor. Of these three wines, you’ll likely find the Produttori del Barbaresco wine the most rustic and earthy, the Gaja wine silkier and sweetly fruity (although there are trademark notes of cinnamon and rose petals amid all that fruit). The Moccagatta wine has a great balance of sweet and savory elements, and is, of the three, probably the most readily drinkable—its tannins don’t have quite the bite of the other two.

Bartolo Mascarello Barolo, $$$

Pio Cesare Barolo, $$$

Aldo Conterno Barolo, $$$

As compared with the Barbaresco flight above, you’ll likely find these wines to be deeper, darker, and earthier, with scents of tar, cedar, and tobacco intermingled with the dried cherry-berry scents of nebbiolo. They are rich and tannic wines, to be sure, but there’s a perfumy quality that makes them more readily comparable to pinot noir than to “bigger” reds from cabernet sauvignon or syrah. Start this flight with the Mascarello wine, the most traditional in style, then move into the Pio Cesare and Aldo Conterno bottlings. The Mascarello wine is probably the most fruit-driven, with bright and expressive aromas and a certain delicacy on the palate. The Pio Cesare is a little more extracted, with a touch more black fruit character, as is the Aldo Conterno. The Conterno is aged in newer, smaller oak barrels, lending it more toastiness and preserving its inky color; the Mascarello wine is aged in traditional, larger casks, giving it a more oxidative, resiny aroma and a lighter color; the Pio Cesare finds a balance between the two.

La Scolca Gavi, $

Villa Sparina Gavi di Gavi “Etichetta Gialla,” $$

Cool, clean, and crisp: that’s Gavi. In this comparison, you’ll likely find the La Scolca has a more pronounced minerality, a chalkiness on the palate. The Villa Sparina is a bit fatter, dewier. Both wines are delicately aromatic, offering a whiff of green apples and green melon, and they clean up on the finish with a whisk of acidity. With a salad or maybe a pasta sauced with a pesto from nearby Liguria, this type of wine is at its best.

Ceretto Arneis “Blangé,” $

Cascina Ca’ Rossa Roero Arneis “Merica,” $

F.lli Brovia Roero Arneis, $

More assertively aromatic than Gavi’s cortese, Roero’s arneis is a bright, tingly white tailor-made not only for pastas seasoned with mountain herbs but for grilled and roasted seafood of all stripes. There’s a smoky quality to the aroma of arneis, along with hints of white flowers and white grapefruit. The distinctions to be made among these three wines are fairly subtle: the Ca’ Rossa is probably the fullest-bodied, although all three are characterized by a citrusy acidity and lilting aromas that distinguish them from a mass of more neutral, bland-tasting Italian whites.

Michele Chiarlo Moscato d’Asti “Nivole,” $$

Paolo Saracco Moscato d’Asti, $$

The peachy sweetness of moscato is checked with a dose of bracing acidity in these two popular bottlings, two of the best examples around of Moscato d’Asti. Made in the frizzante (semi-sparkling) style, they are sweet without being cloying, with moderate alcohol levels for after-dinner sipping. Try them alongside some biscotti or a bowl of fresh berries; if you’re feeling decadent, pour a little of the wine in the bowl with the berries and toss it around. The sweet, peachy, floral flavors of the wine lend an exotic edge to the fruit.

To download a PDF of this image, visit http://rhlink.com/vita010