The oldest Shintō cosmology presents merely a particular form of the ordinary tripartite division of the visible universe into the upper world of the firmament where the gods and goddesses dwell and where they settle their affairs in tribal council under the authority of the great deities of the upper sky, the middle world of men on the surface of the earth, and the lower world of darkness where live evil and violent spirits ruled over by the great earth mother. The lower world is called Yomo-tsu-Kuni or Yomi-no-Kuni, with a probable meaning of “The Night Land.” The domain of living men is Utsushi-yo, “The Manifest World.” The upper world of everlasting felicity is called Takama-ga-Hara, meaning “The Plain of the High Sky.” It is, first of all, the visible heavens where reside the mysterious powers that make the winds to rush and roar, the storm clouds to gather, the thunders to roll and the lightning to flash, wherein are bodied forth the great spirits of the sun and moon and over-arching sky. The story of how divine beings were sent down from this world in the sky and of how they created the islands of the Japanese archipelago and gave it life in gods and goddesses and all other living things of nature, including man, and of how from these came the primitive society and the state, will be taken up for detailed examination later in connection with the study of the use that is made of the early Shintō world-view in the modern educational system.

This archaic nature mythology, picturing a world in the firmament where the kami first dwelt, has been permeated and modified by memories of old ancestral homes and early tribal wanderings. The precise origins of the different racial stocks that entered into the formation of the ancient Japanese people are unknown. Various theories are held. When authentic history dawns the stock is already mixed. A primitive, negroid, small-statured people, Ainu from the north, Mongolian peoples from the continent who entered the islands by way of Korea, perhaps from an original home in Asia as far west as the Ural-Altaic region, and a dominant race of warriors from the south, perhaps from south China, perhaps from Indonesia, who brought with them to settlements in Kyūshū and Yamato a highly developed rice culture and an exalted chieftainship of sun-descent—all these different elements are, to judge from available evidence, merged with varying contributions of blood and institution in the community of Old Japan.

It is only natural, therefore, that there should be many different interpretations of Takama-ga-Hara in the sense of an actual geographical locality. Places that have been suggested by Japanese scholars as related to tribal movements within Japan proper are Yamato, Hitachi, Ōmi and Kyūshū. Outside of Japan proper, Manchuria, Kwantung, the Ural-Altaic region, Indonesia, the ancient cultural area comprised in northern Burma and southern Tibet, as well as Babylonia and Asia Minor, have all had their advocates.

Various other interesting interpretations of Takama-ga-Hara have also been advanced by Japanese students, such as the sacred and ideal world created by the religious faith of the Japanese people, a figurative expression for the earthly dwelling place of the emperors, in other words, the imperial capital, the state of pure spiritual existence and freedom from all care and, finally, the sun, as the home of the Great Goddess, Ama-terasu-Ōmikami.

In the preceding paragraphs occasion has already been found for introducing the important term, kami. It will be necessary to make constant use of it in the ensuing pages and, at this point, in connection with the elucidation of the main characteristics of Old Shintō, its primary significance should be carefully noted. No other word in the entire range of Japanese vocabulary has a richer or more varied content and no other has presented greater difficulties to the philologist.

The most comprehensive and penetrating account of the meaning of kami that has appeared in Japanese literature was given by the great eighteenth century scholar, Motoori Norinaga. Written long before the age of the modern study of folk psychology had dawned, his analysis, in spite of certain insufficiencies, yet may be taken to stand as a remarkable and almost classical definition of the now widely used term, mana.

He says,

“I do not yet understand the meaning of the term, kami. Speaking in general, however, it may be said that kami signifies, in the first place, the deities of heaven and earth that appear in the ancient records and also the spirits of the shrines where they are worshipped.

“It is hardly necessary to say that it includes human beings. It also includes such objects as birds, beasts, trees, plants, seas, mountains and so forth. In ancient usage, anything whatsoever which was outside the ordinary, which possessed superior power or which was awe-inspiring was called kami. Eminence here does not refer merely to the superiority of nobility, goodness or meritorious deeds. Evil and mysterious things, if they are extraordinary and dreadful, are called kami. It is needless to say that among human beings who are called kami the successive generations of sacred emperors are all included. The fact that emperors are also called ‘distant kami’ is because, from the standpoint of common people, they are far-separated, majestic and worthy of reverence. In a lesser degree we find, in the present as well as in ancient times, human beings who are kami. Although they may not be accepted throughout the whole country, yet in each province, each village and each family there are human beings who are kami, each one according to his own proper position. The kami of the divine age were for the most part human beings of that time and, because the people of that time were all kami, it is called the Age of the Gods (kami).

“Furthermore, among things which are not human, the thunder is always called ‘sounding-kami’. Such things as dragons, the echo, and foxes, inasmuch as they are conspicuous, wonderful and awe-inspiring, are also kami. In popular usage the echo is said to be tengu1 and in Chinese writings it is referred to as a mountain goblin….

“In the Nihongi and the Manyōshū the tiger and the wolf are also spoken of as kami. Again there are the cases in which peaches were given the name, August-Thing-Great-Kamu2-Fruit, and a necklace was called August-Storehouse-shelf-Kami. There are further instances in which rocks, stumps of trees and leaves of plants spoke audibly. They were all kami. There are again numerous places in which seas and mountains are called kami. This does not have reference to the spirit of the mountain or the sea, but kami is used here directly of the particular mountain or sea. This is because they were exceedingly awe-inspiring.”3

Much similar material could be adduced from Japanese sources. It is impossible to consider it within the scope of the present discussion. Summarized briefly, it may be said that kami is essentially an expression used by the early Japanese people to classify experiences that evoked sentiments of caution and mystery in the presence of the manifestation of the strange and marvellous. Like numerous other concepts discoverable among ancient or primitive peoples, kami is fundamentally a term that distinguishes between a world of superior beings and things which are thought of as filled with mysterious power and a world of common experiences that lie within the control of ordinary human technique. Often the best translation is simply by the word “sacred.” In this sense it has an undifferentiated background of everything that is strange, fearful, mysterious, marvelous, uncontrolled, full of power, or beyond human comprehension. The conviction of the reality of the world that it registered was supported by the experience of extraordinary events, such as the frenzy of religious dances, or by outstanding objects that threw the attention into special activity, such as large, or old, or strangely formed trees, high mountains, thunder, lightning, storm and clouds, or by implements of magic, or by uncanny animals, such as foxes, badgers, and manifestations of albinism. These old attitudes exist in the present and strongly influence modern Shintō.

As this sacred, mysterious background became more and more articulated with the progress of experience and thought, descriptive elements were attached to the word, kami, and the names of the great deities were evolved, as, for example, Ama-terasu-Ōmikami, “Heaven-shining-Great-August-Kami”, for the Sun Goddess, or Taka-Mimusubi-no-Kami, “High-August-Producing-Kami,” the name given one of the creation deities or growth principles of the old cosmogonic myth.

In addition to the general sense of sacred as just outlined, the specific meanings of kami should be noted. They are: spirits and deities of nature; the spirits of ancestors (especially great ancestors, including emperors, heroes, wise men and saints); superior human beings in actual human society, such as living emperors, high government officials, feudal lords, etc.; the government itself; that which is above in space or superior in location or rank (declared, without warrant, by some Japanese scholars to be the primary meaning); “the upper times,” i.e., antiquity; God; the hair on the human scalp; paper.

Evidence which cannot be cited here goes to show that the classification of the hair on the human scalp under the kami concept had probable origin, not in the very apparent fact that the hair was on the top of the head and hence “superior,” but in the association of the hair with a primitive supernaturalism or with the idea of mysterious superhuman force.4

Kami in the sense of paper may be a totally unrelated word. It has been suggested, however, that it found its way into the sacred classification because of its unusual importance in the social life.

A phonetic variation of kami is kamu (or kabu), the latter being perhaps the older term. Kamu strikingly resembles in both word form and meaning the tabu (sometimes written kabu or kapu) of Polynesia, from which the term taboo is derived. The Ainu kamui is also worthy of comparative study in this connection.

Another term, mi-koto, is frequently affixed to the descriptive elements of divine names as a substitute for kami. This also will be encountered here and there in the pages that follow and its meaning should be explained at this point. The parts signify: mi (honorific) and koto (“thing” or “person”). The word was originally a title of reverence applied to exalted individuals in the ordinary social life. It is sometimes used of the gods and in such cases is perhaps best translated “deity”, as, for example, Susa-no-Wo-no-Mikoto, “The-Impetuous-Male-Deity,” the name commonly given the storm god.

Shintō gods and goddesses are sometimes referred to in the literature as the “deities of heaven and earth.” As already mentioned, Shintō itself is sometimes called the Way of the Deities of Heaven and Earth. The terminology is an old one and appears in the early writings in the form of a distinction between the so-called amatsu kami (“deities of heaven”) and the kunitsu kami (“deities of earth”). This has caused a bit of perplexity to the commentators. A favored, though problematical interpretation, takes “heavenly deities” in the sense of the original kami of the dominant Yamato tribe. They are the gods and goddesses of Takama-ga-Hara. The “earthly deities” are understood to be those which were already being worshipped in the land when the early representatives of the Yamato race entered it. Both terms are interpreted, without good grounds, in a legitimate ancestral sense as ancient chieftains.

In general outline the mythology of old Shintō is closely similar to what is found almost universally among other peoples at like stages of culture. The great deities are the unknown forces of nature formulated in terms of the current social and political patterns. The justification of these statements will be given in detail at a later point in the discussion. Yamato culture, in the form which eventually became preeminent, centered in the adoration of the sun. Dynastic interests were quick to make the most of the uniqueness and majesty deriving from claims for the descent of the Imperial Line from a solar ancestry. By the sixth century of the Western era an imperial solar ancestralism had become the paramount motive in the Yamato state worship. Its influence has widened with the passing centuries until today it constitutes the predominant interest of all Shintō.

Study of the early rituals indicates that the primary interests expressed in the public religious rites were to safeguard the food supply, to ward off calamities of fire, wind, rain, drought, earthquake and pestilence, to obtain numerous offspring and peaceful homes, to secure the prosperity and permanence of the imperial reign, and to effect purgation of ceremonial and moral impurity.

The earliest worship of the kami was not necessarily at man-made shrines. Mountains, groves, trees, rivers, springs, rocks, and other natural objects served as primitive sanctuaries. The oldest shrines known to have been constructed by human hands were simple taboo areas formed by the dedication of sacred trees and stones. We do not know when houses first began to be built for the gods. The date is lost in the mist of antiquity. Man-made shrines, copied from the dwellings of chiefs, must have appeared very early in the historical development, however. The records of the oldest existing shrines of the present, that of Ōmiwa in Yamato and that of the great shrine of Izumo, state that these edifices were first built in the Age of the Gods. By the time of the compilation of the Engi Shiki in the tenth century of the Western era the shrines had become sufficiently numerous and diverse to be graded into so-called upper, middle and lower classes. A census given in this document names 2,861 shrines. It is improbable that this figure exhausted the list for the entire country.

The oldest and most important of the festivals were connected with agriculture. There were spring ceremonies for the purification of fields and seeds, for the invocation of divine protection to the growing crops, and the warding off of unfavorable influences of wind and water. There were harvest festivals of thanksgiving and communion and of the dedication of first fruits. Group worship was effected by music and dance, by representative prayer, and by the presentation of offerings. Ordinary offerings were of food—rice, greens, vegetables, fish, birds and the trophies of the hunt—sometimes of horses, weapons, and farm implements. It appears that in the earliest formative period there was no special order of priests. A natural priesthood developed in the family and tribal headship. Later, but at early and unknown dates, four priestly classes emerged: the Ritualists (Nakatomi), the Abstainers (Imibe), the Diviners (Urabe), and the Musicians and Dancers (Sarume). The earliest known representatives of the last named group were women. The fact that these “dancers “bear the same root name (saru) as that given the chief of the phallic deities (Saru-ta) would seem to point to a function as temple prostitutes or fertility maidens. Right up into modern times prostitution has had a close association with some of the largest Shintō shrines. The four priestly classes maintained themselves in hereditary corporations or families. Subordinate offices of priests are also mentioned in the literature.

The Ritualists had charge of ceremonies and read the norito or the state rituals. It was the duty of the Abstainers to ward off threatened pollution by the practice of restraint and caution toward contaminating objects and acts, and thereby maintain open and uninterrupted the channels of communication between man and the holy power of the kami. An ancient Chinese book, cited by Aston in his translation of the Nihongi, says that the Japanese “abstainer” was not allowed to comb his own hair, wash his own face, eat meat, or approach women.

The will of the kami was learned in an esoteric art of divination, known and practiced by the Urabe. The preferred method of original Japanese usage was to read the omens from the marking that appeared on bones that had been previously scorched in fire. The shoulder-blade of the deer was commonly employed for this purpose. Later, under Chinese influence, tortoise shells were substituted for bones. As late as 1928, in connection with the coronation ceremonies of the reigning Emperor, the sites of fields in which to grow the sacred rice for use in the communal meal between the new ruler and the ancestral spirits were determined by state divination in which the will of the gods was read in markings that appeared on roasted tortoise shells. The early literature furnishes evidence that the will of the kami was also ascertained through oracles received at the shrines, as well as through dreams, the ordeal of boiling water, and special revelations made to those in a state of trance or religious ecstasy. Any unusual event was taken as an omen, good or bad. Strange circumstances in the catching of fish, the coming of darkness in the day time, spiders on the garments, the migration of rats, thunder, the finding of a three-legged crow, albinism in animals, the remarkable behavior of dogs, foxes and other creatures, these and scores of similar events all bore occult meanings wherein the hidden will of the kami was revealed.

Various ritualistic procedures were devised for the expurgation of contamination, whether physical, ceremonial or ethical, for the averting of ill-luck, the avoidance of calamity and the breaking of the magic of curses, spells and incantations. Uncleanness might arise in many ways. It might come through contact with actual physical filth, or through sickness and pestilence visited on man as punishment from the gods or by the caprice of unclean and evil spirits, or, again, through the contamination of natural calamities such as earthquake and fire, which, again might be the expression of divine wrath or malign curse. Corpses, blood (wounds, killing of animals, menstruation, child-birth, etc.), leprosy, sores, boils, bunions, warts, sexual intercourse, incest, bestiality, the voiding of excrement, the flaying of animals alive or backward, as well as overt acts of ordinary ethical significance, such as injury to the rice fields and the destruction of animals belonging to another, all were sources of defilement and required ritualistic purification.

The earliest known purification process was by the ablution of the naked body of the defiled person in the waters of the sea or of rivers. The first recorded rite of this sort was carried out in salt tide-water at a river’s mouth. Even today the objects with which ceremonial defilement is removed in Shintō ceremonies are cast away on running water, thrown into the sea, or burned in “pure fire”, i. e., fire kindled with a bow-drill and dedicated to the kami. At the great shrine of the Sun Goddess at Ise, worshippers, prior to drawing near to the sacred presence, still purify themselves by rinsing hands and mouth with the waters of the Isuzu River. Later, purification was accomplished by sprinkling with hot salt water and by scattering salt about in the place to be purified, or by presentations of salt. The practice has persisted to the present, not only at the shrines but also in the ordinary secular life. Restaurants and similar public houses are purified daily in modern Japan by the erection of three cones of salt at the threshold. Salt-scattering rites and salt presentations are still commonly utilized at the shrines and in the general social life to effect purification. In such usage salt has a magical efficacy associated with an empirically discovered rational therapeutic and is also a symbol of the earlier cleansing in the salt water of the sea. A personal purification, symbolic of the earlier complete ablution of the body, has also survived in the generally observed “hand-water” rite of the modern shrines in which, prior to drawing near the kami, the worshippers pour water from the sacred font on their hands and rinse their mouths.

General purification of the entire nation was carried out twice each year, namely, in the sixth and the twelfth months. This was the so-called Great Purification (Ō-harai). The method included abstinence on the part of the priestly abstainers, expurgation by waving a wand-like ceremonial device (ōnusa) over the people, the reading of the purification ritual by the priests, and the presentation on the part of the people of penalty-offerings representative of the ordinary commodities of the social life such as cloth, horses, swords, bows and arrows, skins of animals, mattocks, sickles, and uncooked food. Essentially the same purification methods are in use at the shrines today.

Personal purification was also effected by the magical transfer of contamination to some representative object. The most widely used method made use of substitutionary images of the human form in the shape of small dolls of paper or metal. These were rubbed on the person and then cast into the waters of rivers or sea in the belief that sin and defilement were thereby transferred to them and carried away. Paper images of this sort were distributed to all the people prior to the celebration of the Great Purification Ceremony. Contemporary Shintō still maintains the ancient usage.

The second main phase of Shintō history extends for some thirteen hundred years between the time of the rise of Japanese Buddhism at the close of the sixth century of the western era and the passing of the Buddhist eclipse of Shintō, which, on the institutional side, should be made to begin with the Restoration of 1868. The year 552 A.D. is generally accepted as marking the date of the official introduction of Buddhism into Japan, although the earlier date of 538 A.D. is favored by some. Buddhist influences had undoubtedly begun to seep slowly into the land at a much earlier period, perhaps for a century or two prior to the dates given above.

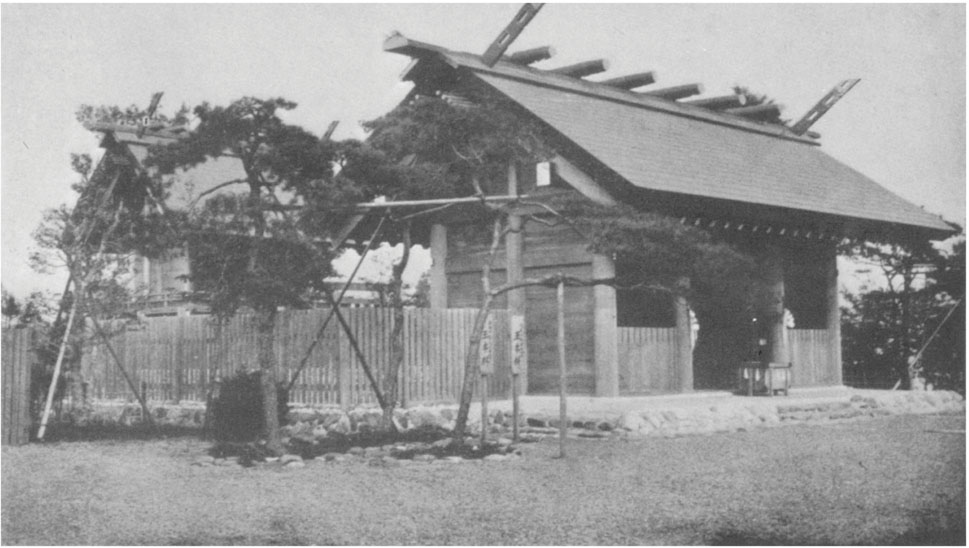

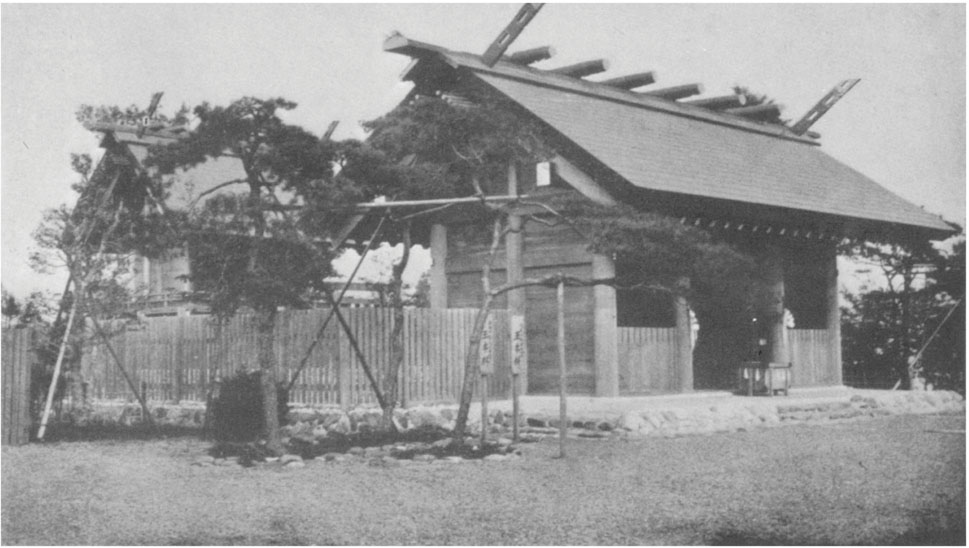

The Iseyama Shrine of Yokohama

Although this shrine is of recent construction it shows the influence of a very primitive style of Shintō architecture.

Confucianism appears to have found its way into Japan about a century and a half before the recognized date of the formal introduction of Buddhism. The exact date is not known.5 The former, as compared with the latter, centered more definitely in the affairs of human society and emphasized a political morality that promoted the harmony of classes through the inculcation of obedience on the part of the ruled and education in intelligent virtue on the part of those ruling. Confucianism was not at first a great influence on the religion of the rank and file of the people, although it was accompanied by a certain amount of continental superstition that both stimulated and supplemented the native folklore and which found expression in the worship of caves and mountains, prayers and ceremonies for the production of rain and the worship of Heaven. On the side of more positive contributions to Japanese culture, Confucianism strengthened, if, indeed, it did not actually create, early Japanese ancestor worship and gave greater definiteness to the more vague and original conception of kami. It promoted family sentiment and furnished Japan with an exact, though sometimes sterile and artificial social and political etiquette, which, in spite of irrepressible tendencies in the Japanese character to seek newer and freer forms, has exercised a profound influence on the total historical development, particularly in the field of moral education.

Under its entry for 552 A.D. the Nihongi records that the king of the country of Pèkché in Korea sent to the Japanese Emperor, Kimmei Tennō, an image of Shaka Butsu in gold and copper, together with presents of banners and umbrellas and a number of volumes of the Buddhist sutras. Accompanying these was an important memorial wherein the merits of the new teaching were highly extolled:

“This doctrine is among all doctrines the most excellent. But it is hard to explain and hard to comprehend. Even the Duke of Chow and Confucius had not attained to a knowledge of it. This doctrine can create religious merit and retribution without measure and without bounds, and so lead on to a full appreciation of the highest wisdom. Imagine a man in possession of treasures to his heart’s content, so that he might satisfy all his wishes in proportion as he used them. Thus it is with the treasure of this wonderful doctrine. Every prayer is fulfilled and nought is wanting. Moreover, from distant India it has extended hither to the three Han, where there are none who do not receive it with reverence as it is preached to them.”6

From this time onward throughout its entire subsequent history a major problem of Shintō has been that of adjustment to the “treasure of this wonderful doctrine.” In the earlier stage of this relationship the adjustment was largely that of wholesale absorption of the more naïve and less experienced Shintō into the body of its great rival. For centuries Shintō found itself more or less helpless in the presence of the more profound doctrinal content and the more aggressive priestly leadership of Buddhism.

Early Buddhist progress in the Japanese field was, however, not due merely to the possession of a richer speculative element and a more skillful leadership. Buddhism was the chief mediating agency of that great tide of higher continental culture which had already begun to move over Japan in the aftermath of the Korean expedition of the great warrior Empress, Jingo Kōgō, beginning with the close of the fourth century of the western calendar. For, along with Buddhism came improved methods in nearly all the skilled occupations of the time, in weaving, brewing, metal working, road and bridge building, the digging of wells and canals, ceramics, architecture, sculpture, painting, embroidery, wood carving, forestry, sericulture, and agriculture. Buddhism brought with it literature, art, astronomy, medicine, education and more definite and humane social and political institutions. It stimulated compassion through its central teaching of jihi, or benevolence, and deepened the sense of human equality. It broadened toleration and fostered the love of natural beauty. It brought resplendent rituals and an idealistic philosophy. It established monasteries and alms houses and brought relief to famine and pestilence. It distributed free clothing to the needy and free medicine and hospital service to the sick. It introduced Japan to a noble ethical code and heightened the expectation of life beyond death. No other influence, with the single exception of the modern scientific-industrial revolution, has so modified Japanese civilization.

Little wonder that not long after its introduction Japanese rulers were so concerned to find in Buddhism practical influences for strengthening and enriching the state. Nor were they beyond a belief that Buddhism offered a superior ceremonial magic for drawing down into human realms a maximum of favorable supernatural aid, as witnessed by the appearance of an almost fanatical devotion to the reading of luck-bringing sutras. Their interests were not merely political and economic, however; some at least there were who were sincerely appreciative of the higher Buddhist ideals. Shintō opposition was at first intense, even belligerent, but was obliged to compromise in proportion as patrons of the new learning multiplied in official circles. Chief among these was the royal protagonist Shōtoku Taishi (572–622 A.D.), a prince who has been well named the Constantine of Japanese Buddhism, a scholar-statesman whose liberal syncretism opened a golden age to the new religion, both as a cultus and as a metaphysic. Beginning with the close of the sixth century the literature presents a story of extraordinary popularity in high places, of emperors and important officials accepting the new faith, of sutras read and expounded under government direction, of Buddhist services in the palace, of the regulation of Buddhist affairs by imperial decree, and, finally, of the propagation of Buddhism by imperial order and the acceptance of Buddhist festivals as affairs of state.

The Nihongi is full of the details of this remarkable expansion. A census of the date of A.D. 623 reports forty-six temples, eight hundred and sixteen priests and five hundred and sixty-nine nuns. The chronicle for the last day of the last month of the year A.D. 651, written almost one hundred years after the introduction of Buddhism, says that on this day two thousand one hundred priests and nuns were invited to the palace and made to read the Buddhist scriptures. By the year 690 the number of priests attached to the three largest temples totaled three thousand three hundred and sixty-three. The prophecy attributed to the great Buddha, “My law shall spread to the east,” was being richly fulfilled.

By the opening years of the ninth century the doctrinal assimilation of Shintō to Buddhism was well under way. The first comprehensive attempt in this direction was made by the priests of the Tendai sect of Buddhism. To their scheme of thought they attached the name of Sannō7 Ichi-jitsu Shintō, meaning “Mountain-king One-truth Shintō.” The title, Sannō, “Mountain-king,” or “Mountain-ruler,” was originally applied to the deity of Mount Tendai8 in China, the holy land of this sect and the seat of a well known monastery. Ichi-jitsu, “one truth,” or “one reality,” is an expression taken from the Hokke Kyō, “The Lotus of Truth,” that is, from the Sad-dharma Pundarika sutra, the primary sacred scripture of Tendai, and is part of a sentence, reading in translation, “All the Buddhas that come into the world are merely this one reality (ichi jitsu).” The reference is to the fundamental Tendai doctrine of a single, absolute reality behind all things and manifested in the multiform phenomena of the universe. Beyond all appearances, but ultimately causal to all events of time and place, is the transcendent, non-observable unity of existence, the primordial Buddha. This primary reality takes form in the phenomenal world in an infinite varity of things and events, including the various divine beings of religion, and in the observable sphere the episode of chief significance attaches to the historical Buddha. The manifest Buddha is the special temporal revelation of the transcendent Buddha. Unity in the phenomenal world is again discovered in a universal activity which expresses itself in the interrelation of all the events of time and space. Thus the absolute and transcendent is united with the concrete and phenomenal through an orderly mutuality of physical and moral causation. As an instrument of theoretical syncretism such a system can hardly be improved upon.

A remarkable aspect of this speculation is the extraordinary manner in which it anticipated by over a thousand years some of the fundamental propositions of modern philosophy.

Starting with a unity so comprehensive, the equation of particular events in the observable world was simply a matter of convenient choice. The result was that, as specifically applied to the syncretism of Buddhism and Shintō, the name Ichi-jitsu (“One Reality”) was taken to mean that the various gods and goddesses of the latter were the appearances in the Japanese historical sequence of corresponding Buddhist divinities, and all the manifestation of the one transcendent Buddha. This concept has served the scholars of various generations as a facile instrument of interpretation and has enabled them to preserve their metaphysical balance while holding onto Shintō with one hand and Buddhism with the other. It has, however, done much more than this. It has undergirded Shintō with a bed-rock of self-consistent philosophy. Every system of thought in Shintō history that has approached comprehensiveness on the philosophical side has been pantheistic. For this Shintō is chiefly indebted to Buddhism. This in turn has meant that the fortunes of Shintō, in so far as they have been related to the attempt to evolve speculative doctrine, have been so interrelated with those of Buddhism that the former have risen and fallen with the latter. On the other hand, the phase of Shintō that has been identified primarily with Japanese nationalism has prospered with the growing integration and expansion of the state life, especially in modern times.

The Sannō system has sometimes been attributed to the great priest, Saichō (767–822 A.D.), the founder of the Tendai Buddhism of Japan, better known by his posthumous name of Dengyō Daishi. But there is nothing in his acknowledged writings to support this view apart from a generous attitude toward Shintō. It is possible, however, that he did propound ideas that were later organized into the tenets of the Sannō school. Actual systematization was made by his later disciples. This movement can be traced as a definite school of thought from the Heian era onward, beginning with the opening years of the ninth century. In the Tokugawa period the priest, Tenkai, zealously propagated this form of Shintō and contributed effectively to its defense in the presence of rival schools.

The chief center of Sannō influence was the seat of the Tendai sect on Mount Hiyei near Kyoto. Through the assiduity of the priests congregated there, Buddhist divinities (hotoke) in great numbers were assimilated with specific kami. At the height of Sannō influence there stood on Hiyei Zan twenty-one large Shintō-Buddhist shrines and one hundred small ones. Sannō shrines were likewise multiplied throughout the country.

Far more potent, however, as a means of fusing the fortunes of the two great faiths of mediaeval Japan was the system worked out by the priests of the Shingon sect of Buddhism, to which the name Ryōbu (“Dual”) Shintō has been given. “Dual” is here used with reference to the two phases of reality differentiated in Shingon metaphysics, namely, the matter and mind, or the male and female, or the dynamic and potential, aspects of observable things. In Shingon terminology the material or dynamic aspect of cosmic existence—earth, water, fire, wind and their interactions—are included in the so-called Taizō Kai (“The Womb-store Cycle”), while the ideal aspect of the universe makes up the so-called Kongō-kai (“The Diamond Cycle”), that is, the world of permanence. The significance of the title, Ryōbu Shintō, then, is Shintō interpreted under the forms of these two categories. In the specific application of the inventory, the traditional Japanese deities are listed, some in the Womb-store Cycle, some in the Diamond Cycle.

The original formulation of the system has been attributed to Kōbō Daishi (774–835 A.D.), the founder of the Shingon sect of Japanese Buddhism.9 He was probably not the author, however, but merely taught elements that were later incorporated into Ryōbu Shintō. The name itself did not appear until long after the principles of amalgamation for which it stands had emerged. It was probably first used as the designation of a school of Shintō by Yoshida Kanetomo (also known as Urabe Kanetomo—1435–1511 A.D.) and his followers at the close of the fifteenth century. From this time onward it is common in the literature.

The system itself is much older and, beginning with the opening years of the twelfth century and extending down to modern times, has exerted a tremendous influence on Shintō history. In the period lying between the first years of the sixteenth century and the middle of the nineteenth nearly all the shrines of the country were touched by it. It met with relentless attack from the scholars of the Pure Shintō school in the Tokugawa period and, with the forced separation of Buddhism and Shintō that was effected in the early part of the Meiji era, practically disappeared as a system of doctrine and ceremony. Yet even today there are relatively few shrines that do not reveal, at least in architecture, the effects of their long association with Buddhism.

Ryōbu Shintō developed vigorously in the first half of the thirteenth century during the Kamakura period and, as has just been indicated, was the dominant form of Shintō at the height of the Japanese middle ages. Under its pervasive influence Shintō tended to lose more and more its unique character and to take on the coloring of Buddhism. Joint Shintō-Buddhist sanctuaries were set up, served by an amalgamated priesthood (shasō). Buddhist rites were conducted at Shintō shrines, and the priests read the sutras to Japanese deities worshipped under Buddhist names. This intimate relationship was, on the whole, to the advantage of Shintō, for thereby its ethical content was deepened and broadened and, as in the case of the fusion with Tendai, a road was opened to a wider philosophical outlook.

Shingon brought to its task of absorbing Shintō a wide experience in unifying the god-worlds and folklore of the peoples that Buddhism had met in its long journey across Asia.

“The Buddhism advocated and propagated by Kūkai [Kōbō Daishi] was an all-embracing syncretism of a highly mystical nature. Its scheme extended the Buddhist communion to all kinds of existence, and therefore to all the pantheons of the different peoples with which Buddhism had come into contact. In embracing the deities and demons, saints and goblins, Hindu, Persian, Chinese and others, into the Buddhist pantheon, Shingon Buddhism interpreted them to be but manifestations of one and the same Buddha.”10

The principle of accommodation made use of in the merging of Shintō and Shingon is not essentially different from that utilized by the priests of Sannō Ichijitsu Shintō. Japanese scholars commonly refer to this as the principle of honji-suijaku, meaning “source-manifest-traces,” the significance being that the fundamental and original reality or source (honji) that exists in Buddhism can be discerned in the appearances or traces manifested (suijaku) by the indigenous Japanese deities. The system posits as its central concept the great cosmic Buddha, the Maha-Vairochana, rendered into Japanese as the “Great Sun” (Dai Nichi), whose essence is the transcendent, non-observable source of all things, whose body is the manifested universe of things and events, and whose vitality is in their interrelated activity. In the manifestation of this Great Life of the Universe on the side of the observable events of experience, the kami of the Shintō pantheon appear as the avatars of the divine beings of Buddhism, and thus these two faiths are in essence one and the same. Each and every Shintō god or goddess is a particular manifestation or suijaku of a special Buddhist divinity existing as honji or source. Thus, the great Sun Goddess of Ise, Ama-terasu-Ōmikami, is equated with Maha-Vairochana and made to stand as the particularized Japanese revelation of the Absolute of Shingon metaphysics.

The syncretistic method thus applied in the attempts of Tendai and Shingon to absorb Shintō has exercised a far-reaching influence on the history of the latter. As the sequel will show, ir is widely followed by the theologians of the modern Shintō sects in defense of the pantheistic nature of their basic world view.

Threatened with absorption into the vast assimilative matrix of an all-comprehending Buddhist philosophy, it was inevitable that Shintō, involved as it was with the nationalistic self-assertiveness of the Japanese people, should sooner or later attempt to set itself free. Not only did Shintō defend itself by its in-trenchment in the folkways and by the persistence of its ceremonies, but also various schools arose in direct opposition to Ryōbu Shintō. Only the most important of these can be passed in rapid review in the following paragraphs.

The first goes by the name of Yui-itsu Shintō (also sometimes written Yui-ichi Shintō). In this title, yui-itsu means “only one,” or “one and only,” and is used in juxtaposition to the dual Shintō of the Ryōbu school. That is to say, the former, as distinct from the latter, is Shintō in its true and original mode, with its unique elements separated from the contaminations of Buddhism and also from those of Confucianism. Such it was at least in the conception of its founders. In reality, however, it is still a mixture, not only with Buddhism, but also with Confucianism and Taoism.

This is also sometimes designated Yoshida Shintō and sometimes Urabe Shintō, after the family names of the priests who were responsible for its formulation. The Urabe family furnished the hereditary priesthood of the great Kasuga shrine at Nara and the Yoshida family was a branch thereof. The Urabe priesthood flourished in the Kamakura era (1192–1333 A.D.) and the beginnings of their attempts to rescue Shintō are to be traced to that time. The best known representative of the school, however, was Urabe Kanetomo (1435–1511 A.D.), one of the greatest of the scholarly philosophers of Japanese history. His chief work was done at the beginning of the long period of civil wars that marked the transition to the peace of the Tokugawa régime. Most later Shintoists, in so far as their systems of thought have had in them philosophical vitality, have drawn freely from his deep well of speculation.

At the base of Kanetomo’s thinking is a pantheism that shows definite Buddhist affinities but which at the same time adjusts itself easily to the naturism of Old Shintō. The original kami is regarded as the unknowable, transcendent, self-existent, eternal, spiritual Absolute:

“Kami or Deity is spirit, without form, unknowable, transcending both cosmic principles, the In and the Yō (Chinese, yin yang) …. changeless, eternal, existing from the very beginning of Heaven and Earth up to the present, unfathomable, infinite, itself with neither beginning nor end, so that the so-called “Divine Age” is not only in the past but also in the present. It is, indeed, the eternal now. (Shindaishō).”11

And again:

“The Deity, transcending our senses, is the Divine Void, otherwise called the Great Exalted One (Miōbōyōshū).”12

The influence of Shingon trinitarianism, which he formally repudiated but which in his actual philosophical needs he could not escape, runs through his thinking. For example, he declared that in our interpretations of the divine immanence:

“With reference to the universe we call it kami, with reference to the interactions of nature we call it spirit (rei), in man we call it soul (kokoro). Therefore, God is the source of the universe. He is the spiritual essence of created things. God is soul (kokoro) and soul is God. All the infinite variety of change in nature, all the objects and events of the universe are rooted in the activity of God. All the laws of nature are made one in the activity of God.”13

This, he says, is the central fact of Shintō. In other words, Shintō is an all-comprehending spiritual monism—“All things, organic and inorganic, things sentient and non-sentient, things with spirit and without spirit: all are included in Shintō.”14

The fact gives a philosophical significance to the name, Yuiitsu (“One and Only”). For, since all things, events and activities are ultimately reducible to a single great principle of life or spirit, namely, the Absolute kami, and since this is the basis of Shintō, the name, “One and Only,” i.e., Monistic (Yui-itsu) Shintō, becomes applicable as expressive of the primary nature of this form of belief and practice.15

This is also the explanation of another title sometimes given to Kanetomo’s system, that of Gempon Sōgen Shintō, meaning a Shintō that is “the origin of beginnings and the source of truth.” This signifies a doctrine that aims at the comprehension and interpretation of the very beginning of events and things, a doctrine in which all laws are included in one great cosmic existence or operation, wherein even the unpredictable activities of thle positive and negative principles are reduced to orderly beginnings.

It follows, then, that the Great Life of the Universe has special manifestation in the deities of the Shintō pantheon and also in all the Buddhas. It is of some importance to note in this connection that in accounting for the relationship of the divine beings of these two faiths, Kanetomo reverses the thesis of Ryōbu Shintō and makes the Japanese kami the originals, or honji, and the divine beings of Buddhism the appearances, or suijaku. The argument then moves quickly to a nationalistic point. By virtue of the intimacy and the accuracy of the revelation of the Absolute made through her kami and her people, Japan is preeminently the Land of the Gods, the Divine Country, and her Emperor, descended directly from the Great Goddess, Amaterasu-Ōmikami, is a god revealed in human form. The Emperor rules, not by the will of man, and not merely by right of exalted virtue, but more than this, because of descent in an unbroken line from divine ancestors. We see here the philosophical and nationalistic presuppositions that underlie Shintō in the modern situation taking definite shape as part of a comprehensive speculative system.

The second attempt at a formal declaration of independence from Buddhism which we need to note is Watarai Shintō, so-called from the family name of the group of priests that were chiefly responsible for organizing and propagating the tenets of the school. It is sometimes also called Deguchi Shintō for the same reason, Deguchi being the family name of one of the founders who later changed his name to Watarai. The school is sometimes referred to as Ise Shintō and sometimes as Gcgū (Outer-Shrine) Shintō. The two designations last mentioned arose because of the association of the Watarai priesthood with the Outer Shrine of Ise.

Members of this family as early as the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries achieved distinction through their scholarly attempts to give precedence to Shintō, but the best affirmation of the thought of the school was given by Watarai Nobuyoshi who was born at Ise in 1615 and who in due time followed his ancestors as one of the priests of the Outer Shrine. He died in 1690. Along with his opposition to Buddhism he attempted to make formal repudiation of Confucianism, but, as a matter of fact, he really built on Confucian foundations. In his conception of Shintō as the source of government and as the fountain-head of human conduct, he reveals, in common with most Shintoists of the Tokugawa period and of modern times as well, an inability to construct a satisfactory system of ethics apart from Confucian materials. At the same time he did not altogether escape from the Buddhism which he ostensibly opposed. The pantheistic background of his system is Buddhist. As a matter of fact, his teaching is a garment of many colors, woven from Buddhist, Confucian, Taoist and Shintō threads. Be this as it may, his emphasis on the superiority of the deities of Ise and in particular his exaltation of the ceremonies and beliefs of the Outer Shrine, together with the large place which he gave to divination, were factors in bringing again to the surface the great sub-stratum of Old Shintō that lay buried in the heart of the nation.

Suiga Shintō, the next form of interpretation to be considered in our brief survey of the mediaeval field, branched off from the Yui-itsu and the Ise schools under Confucian influence. Indeed, so strong is the impress of the last named system on it that the famous eighteenth century scholar, Motoori Norinaga, declared that it was nothing other than a scheme for the utilization of the Shintō classics for the purpose of propagating Confucian doctrine.

The name, Suiga, is derived from a passage in one of the texts of the Shintō Gobusho,16 which reads in translation: “Divine grace depends first of all on prayer; the divine protection has its beginning in uprightness.” The second ideographic element in the term here rendered “divine grace “(sui of shinsui) and the second element of the term translated “the divine protection” (ga of myōga) are combined to form the title Sui-ga. The name thus signifies a Shintō that is concerned with the presence and providence of God.

The founder was Yamazaki Ansai. Born at Kyōto in 1618, he spent his early years in the study of Buddhism and later devoted himself to the Japanese classics and Chinese science. At one time he was the head of a school for young samurai in Yedo. He died in Kyōto in 1682.

Yamazaki declared that he expounded a doctrine that had been taught by the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu-Ōmikami, and communicated through successive kami to her human descendants. He said:

“The parent deities, Izanagi and Izanami, following the truth of the positive and negative principles, taught the way that men should ever follow, and after this Amaterasu-Ōmikami, possessing the Three Sacred Treasures [the mirror, the sword and the necklace], ruled over the land within the seas [Japan]. God is the soul of the universe; man is the god-stuff of the world.”17

All events and things in the realm of the observable are the result of the interaction of two principles or forces, one centripetal, which he designated tsuchi, the reading of the ideogram for earth, the other centrifugal, indicated by the term, kane, one of the readings of the ideogram for metal. These two are ever inseparable; their mutual activity sustains the universe, appears in the operation of the positive and negative influences of Chinese philosophy, and makes humanity possible.

The monistic or yui-itsu doctrine of Urabe Shintō is expounded in the sense of the oneness of the divine and the human. There is but one ultimate reality: it appears in the identity of God and man. In the age of the Gods the affairs of Heaven had expression in terms of the affairs of men and the activities of men had divine significance. In the social and political life the teaching and virtues of the Sun Goddess must be the standard of the nation. The greatest of all virtues is reverence.

In spite of the existence of much that is fanciful in Ansai’s teachings, is must be admitted that he did a great deal to further the progress of Shintō, especially in deepening the sentiment of reverence and in heightening the sense of loyalty to the Emperor. In this he was the forerunner of the scholars of the pure Shintō school which must be considered next.

A comprehensive study of Shintō in the middle ages of Japanese history would include various movements of thought in addition to those that have just been outlined.18 It is necessary at this point to pass on to a brief consideration of the most influential of all the nationalistic movements of Shintō, the so-called Fukko school. Fukko means the restoration of antiquity. Fukko Shintō, then, is Renaissance Shintō. Because of its claim to have set itself free from all foreign contaminations, it is frequently called Pure Shintō. It is also sometimes designated Kogaku (“Ancient-learning”) Shintō. To be properly understood it must be studied as an emperor-centered, nationalistic revival which found its main support in an appeal to the documents of old Shintō. The revival may be said to have had its beginning in the attacks on heresy made by Kada Azumamaro (1669–1736), a native of Kyoto, arising out of his conviction that the safety of the nation demanded the revival of the true Way of the Gods, which involved, as a first step, the recovery of the classical Yamato language, forgotten, and almost lost, in a century-long zeal for things Chinese. It is true that Kada’s interpretations of the ancient literature were oftentimes in error and not satisfactory even to himself. In fact, a tradition exists to the effect that prior to his death he burned a large part of his own writings. From the limited sources available it is difficult to know his teachings in detail. We can judge his general position, however, from the fragments that have survived. His principal influence on later generations lay in the pioneer work which he did in philology, in the vigor of his nationalism, and in his ardent opposition to esotericism in philosophy. He declared that if there were such a thing as the Way of the Gods, then even the uninitiated ought to be able to understand it.19

The real foundations of the revival were laid mainly by the three great scholars, Kamo-no-Mabuchi (1697–1769), Motoori Norinaga (1730–1801) and Hirata Atsutane (1776–1843). The source materials for the study of the Pure Shintō Renaissance are to be found mainly in the writings of these three men. In this literature a successful attempt is made to dig through the foreign accumulation due to Indian and Chinese influences and tap the springs of unique Japanese institutions lying in the oldest literary records of the nation. In large measure it dissolved the mediaeval syncretism.

Kamo-no-Mabuchi was born in a village of Tōtōmi province and came from a long line of Shintō priests. He continued Kada’s linguistic studies and by his almost unrivaled mastery of the classical literature and its archaic modes of thought he opened the gates of antiquity to his contemporaries and to later generations alike. At the same time he, himself, learned much from Lao-tse. He followed Taoism in the important place that he gave to the doctrine that the correct principles of human conduct are discoverable in the study of the natural order of the universe.20 Over against this recognition of an indebtedness to China, he advocated an interpretation of Chinese social psychology, as contrasted with that of the Japanese, that was to be repeated after him with ever rising cresendo right down to the present day. He maintained that the individualism and dynastic instability of the former had resulted in constant civil strife and institutional decay, while the loyalty of the latter to a single unbroken line of rulers had imparted to their national organization a character both unique and indestructible.

A similar idealization of the past dominates his philosophy of history. His golden age was in the long ago. The emperors of ancient times, Mabuchi declared, revered above all things else the great deity, Amaterasu-Ōmikami, and in all their relations with the nation manifested her divine power and wisdom. With love and benevolence toward their subjects they ruled over a state that shall never end, conforming intuitively to the natural principles of righteousness revealed in the universe. The peoples of those ancient times, on their part, consistently and intuitively transcended corruption and evil, and court and nation alike served the successive generations of emperors with self-sacrificing loyalty. Thus the land enjoyed security and peace. This is Shintō, the True Ancient Way.

Fundamentally it was a Way of Simplicity for ruler and people alike. Commenting on the degeneration and corruption introduced through imitation of foreign pomp and splendor, he says:

“So long as the sovereign maintains a simple style of living, the people are contented with their own hard lot. Their wants are few and they are easily ruled. But if the sovereign has a magnificent palace, gorgeous clothing, and crowds of finely dressed women to wait on him, the sight of these things must cause in others a desire to possess themselves of the same luxuries; or if. they are not strong enough to take them by force, it excites their envy. If the Mikado had continued to live in a house roofed with shingles, and whose walls were of mud, to wear hempen clothes, to carry his sword in a scabbard wound round with the tendrils of some creeping plant, and to go to the chase carrying his bow and arrows, as was the ancient custom, the present state of things would never have come about. But since the introduction of Chinese manners, the sovereign, while occupying a highly dignified place, has been degraded to the intellectual level of a woman. The power fell into the hands of servants, and although they never actually assumed the title, they were sovereigns in fact, while the Mikado became an utter nullity.”21

Motoori Norinaga, who succeeded Mabuchi in the leadership of the Pure Shintō revival, must be ranked among the foremost of the greatest scholars that Japan has produced. He was born in the village of Matsuzaka not far from the great shrine of Ise and his early years were surrounded by the devout influences of the national worship of the Sun Goddess. A voracious student from childhood, he rose from the obscurity of great poverty to dominate the scholarly world of his day. His critical edition of the text of the Kojiki, with elaborate commentary, compiled in intermittent labor that extended over some thirty-two years of the most creative period of his life, is alone of sufficient merit to entitle its author to a lasting place in the world’s hall of fame. This monumental work has been the starting point of all later studies of this, the oldest extant document in Japanese literature. Born thirty-three years after Mabuchi, he made the acquaintance of the older scholar late in the latter’s life, but not too late to be benefited greatly by his instruction. Motoori was trained in medicine as well as in literary criticism, philosophy, and religion, and although limited in scientific outlook and peculiarly narrowed by misinformed nationalistic prejudice, he yet combined in himself practically the entire scope of knowledge current in Japan in his time.

He formally repudiated Mabuchi’s dependence on Lao-tse, declaring that the latter’s teaching was merely a way of nature, while his, the true Shintō, was a Way of the Gods and, as such, essentially a revelation in a literature and a national psychology, wherein the primary human duty lay in absolute obedience to a divine teaching. This interpretation was resisted by the Confucianists of the time, notably by some of the scholars of the Mito school, who insisted that Motoori’s independence was achieved on paper only and not in fact, that with all his asseverations of a unique Japanese ethics, his fundamental ideas were borrowed from Chinese philosophy.

A summary of Motoori’s main teachings follows. Japan, since it produced the great deity, Amaterasu-Ōmikami, is superior to all other countries of the earth. The Japanese state was instituted in the divine edict of Amaterasu-Ōmikami, wherein she commanded her grandson, Ninigi-no-Mikoto, to go down and take possession of the land and rule over it, himself and his descendants, forever. The divine will that is thus made explicit has been perpetuated in the perfect harmony of the thought, feeling and act that has ever existed between each succeeding ruler and Amaterasu-Ōmikami. The central fact of Japanese history is that of the unbroken eternity of the divine imperial dynasty and this is why Shintō surpasses all other systems. A doctrine of Messianic destiny with reference to all the other people of the earth immediately follows:

“From the central truth that the Mikado is the direct descendant of the gods, the tenet that Japan ranks far above all other countries is a natural consequence. No other nation is entitled to equality with her, and all are bound to do homage to the Japanese sovereign and pay tribute to him.”22

Each and every human act, good or bad, rests ultimately in the will of the gods. Human moral ideas are implanted by the gods and are of the same nature as instincts. The highest duty of the Japanese subject consists in unquestioning obedience to the divine ruler. At the same time, since the Japanese people are naturally and unerringly upright in their practice they require no special system of moral instruction.

The last of the four scholars of the Pure Shintō revival to be noted here is Hirata Atsutane. He was born in the northern district now known as Akita and was junior to the great Motoori by forty-six years. Although Hirata never received the personal instruction of Motoori, yet so great was his devotion to the learning of the senior scholar that he took a vow at Motoori’s grave to become his disciple, thereby registering a zeal for the revival of the Ancient Way that was to dominate and inspire all his subsequent years.

Formed in a smaller mental mold than Motoori, Hirata nevertheless attempted to master the entire range of knowledge current in Japan in his time. His studies included Chinese classics and philosophy, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, medicine, geography, and history, in addition to Japanese classics and literature. He was familiar with such Western knowledge as had seeped into Japan through the medium of trade with the Dutch—the so-called Rangaku—and admitted that he had placed the doctrines of Lao-tse in his service. Though his main interests were those of a scholar, he practiced medicine intermittently at various stages of his life. His writings include treatises on maritime defense, Chinese philosophy, Buddhism, Shintō, medicine and the art of poetry as well as elaborate commentaries on the Japanese classics and discussions of Japanese political institutions and history.

Hirata’s works abound in vast cosmological, geographical and historical speculations, interwoven with extraordinary mythological imaginings, all vividly colored with the pattern of his own nationalistic enthusiasm. Japanese learning—namely, Shintō—he insists, is the chief of all knowledge, the soundest and most inclusive of all the products of the human mind, since whatever there is in foreign science and technique that can be turned to the service of Japan is thereby Japanese learning. In this way Shintō is made to comprehend all the knowledge necessary to man. Japan, as the foremost of the nations, lies on the summit of the globe and was formed first among the lands of the earth by the greatest of the creation deities, Izanagi and Izanami, while all other countries were produced much later by relatively inferior deities out of sea-foam and mud. All the countries of the world, however, owe their origin to the creative activity of Japanese gods and goddesses.

This material superiority of Japan to all other lands is augmented by religious, moral, intellectual and dynastic superiority. Japan produced in Amaterasu-Ōmikami the greatest of all the deities of all religions and thereby attained a preeminence that no land can rival. The superior merits of Shintō make the presence of all other religions not only superfluous but harmful. Every true-born citizen of the Land of the Gods is a descendant of the gods and, by virtue of such relationship, naturally endowed with a true and perfect moral disposition and a matchless courage and intelligence. Members of the Japanese race are thus raised above other peoples by a difference of kind rather than of degree. The imperial dynasty reaches back in unbroken genealogical sequence to the beginning of the world and is destined to endure throughout all time. The Emperor is the true Son of Heaven and as such “entitled to reign over the four seas and the ten thousand countries.”

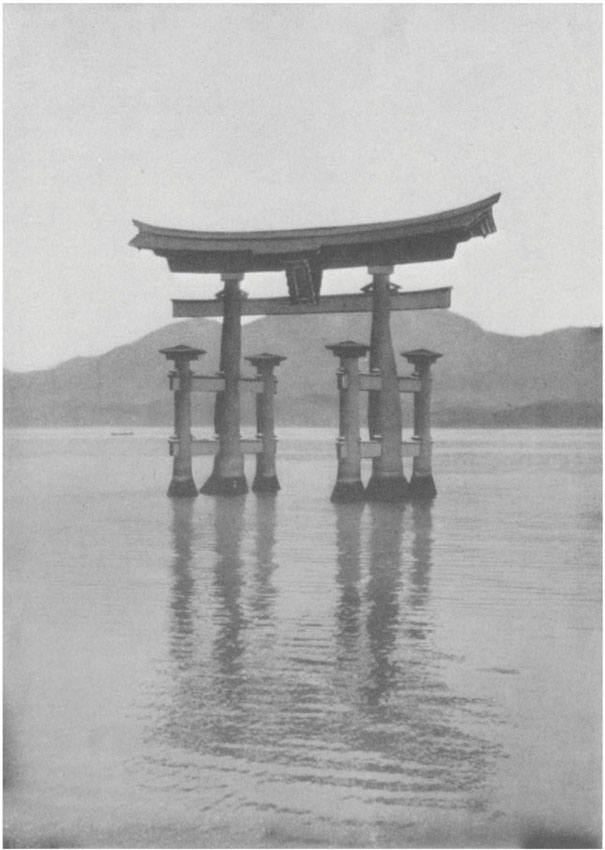

The Approach to the Itsuku-shima Shrine at High Tide

To summarize, Fukko Shintō in its most noteworthy specific characteristics is a revival of loyalty to the Emperor as over against the shōgun and the local daimyō. It declares that in the great national family of Japan filial piety is merged in loyalty, and in this respect departs from traditional Confucianism, which, from the standpoint of Japanese conceptions, exaggerates filial piety within the family at the expense of a higher and wider devotion to the state. It finds assurance of security and continuity for its institutions by an idealization of the past similar to that of the Taika Reform of the seventh century and persuades itself that the peculiar organization of the emperor-centered state life of Japan has kept the land immune from the revolutions and changes of dynasty that have disorganized foreign countries and, in particular, China. It substitutes the Kojiki and the Nihongi for the sutras as sources of authority and interprets the early mythology in such a way as to make the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu-Ōmikami, the founder of the state and the head of the royal line. Fukko Shintō derives from the old literatures the materials out of which to build a resistance against an over-rapid foreign acculturation and, in particular, forges from its ancient sources the instruments of an attack on the Tokugawa usurpation. It relies on a rationalization of history in order to develop the two-fold thesis of a jure divino sovereignty in an Imperial Line unbroken from divine ages and destined to rule Japan eternally and a divine Japanese race which, by virtue of the directness of its genealogical connections with the kami, is braver, more virtuous and more intelligent than all other races of mankind. The god-descended Japanese Emperor is divinely destined to extend his sway over the entire earth; the Japanese race is divinely endowed to do the right thing at all times without the need of the formal and external precepts which less favored peoples are obliged to depend upon. Fukko Shintō thus follows well known patterns in finding the basis of its national pride in the conceptions of a great tradition, a superior culture, a superior racial stock, an unbroken continuity and a beneficent destiny guaranteed under the aspect of eternity. The hold which this form of interpretation of Shintō has gained on the modern Japanese educational system will come to view later in the discussion.

1. A long-nosed, red-faced, winged goblin, supposed to inhabit mountains and forests, thus having a bird prototype. He is associated with those wild spots wherein vague and mysterious sounds and echoes would stimulate feelings of awe.

2 A variant, and perhaps original, form of kami.

3 Motoori, Norinaga, Motoori Norinaga Zenshū (“Complete Works of Motoori Norinaga”), Vol. I, pp. 150–152; edited by Motoori Toyokai, Tōkyō, 1901. Hirata has reproduced this famous passage, with certain modifications, in his Kodō Taii (“Principles of Old Shintō”). See Hirata Atstitane Kōen Shū (“Collected Lectures of Hirata Atsutane”); edited by I. Muromatsu, Tōkyō, 1913, Vol. I, pp. 31 ff. Satow has given an English translation of Hirata’s rendering in Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, Vol. III, pp. 42–43.

4. See Holtom, The Political Philosophy of Modern Shintō, pp. 162–9; Tōkyō, 1922.

5. The date of 405 A.D. is probable for the introduction of the Analects.

6. Aston, Nihongi, Vol. II, p. 66 (edition of 1924).

7. This may also be written Sanō or Sanwō.

8. Tientai, in the Chinese original.

9. For this reason this school is sometimes spoken of as Daishi Ryū, “The Daishi Tradition.”

10. Anesaki, Masaharu, History of Japanese Religion (London, 1930), p. 125.

11. Translated by Katō, Genchi, in “The Theological System of Urabe-no-Kanetomo, “Transactions of the Japan Society of London, Vol. XXVIII, p. 144.

12. Ibid.

13. Miyaji, Naoichi, Jingishi Kōyō (“An Outline of Shintō History”), Tōkyō, 1924, p. 131.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Dr. Genchi Katō has called this the Shintō Pentateuch. It was probably compiled in the thirteenth century by the priests of the Outer Shrine of Ise.

17. Jingi Jisen, p. 459; Art. “Suiga Shintō.”

18. In the summary as given thus far the limitations of space and the purposes of the investigation have required that much be passed by that should be considered in a fuller study. The student of the subject who wishes to go further should note especially:

(1). The Shintō of Kitabatake Chikafusa. Kitabatake (1293–1354) is famous as a loyal retainer of the Southern Court and as the author of several books, the most well known of these being, Jinnō Shōtōki, “The History of the True Succession of the Divine Emperors.”

• In his interpretation of Shintō he attached special importance to the three sacred treasures of the imperial regalia, likening them to the three great lights of heaven: the sun, the moon and the stars—the mirror representing the sun; the necklace, the moon; and the sword, the stars. Again, borrowing from Confucianism, he made them symbolize intelligence, mercy, and strength; and, again, sagacity, benevolence, and courage. The correct principles of government, he declared, start with these fundamental virtues. Where men possessed of these qualities are appointed to office, the rulers are made strong, a proper division of rights and privileges obtains, merit has its true reward, and wrongdoing its just punishment. This, he said, is Shintō and the teaching on which the great ancestress, Amaterasu-Ōmikami, founded the state.

(2). The Shintō of Ichijō Kaneyoshi (1402–1481). Ichijō is known to history as a statesman of merit and as a writer of numerous books. Like Kita-important Shintō movements of the Tokugawa period. Norikiyo’s teaching was opposed by the Shogunate as superstitious and dangerous to public morals (namely, dangerous to the political strength of the Tokugawas) and in 1847 he was exiled to the island of Hachijō. Later he was pardoned by the Shōgun, leshige, but died before the messenger bringing the letter of release could reach his place of exile.

• Uden literally means “Raven-tradition.” The reference is to the raven, called Yata-no-Karasu (or Yata-garasu), sent by the sun goddess to guide Jimmu Tennõ in his expedition to Yamato. “Raven,” read U in Sino-Japanese phonetics, is interpreted as a surname given to a certain Taketsu-Numi-no-Mikoto by Jimmu Tennō for having been his guide. The doctrines advocated by Norikiyo are declared to have been handed down from this “Raven,” hence the title, Uden—“Raven-tradition.”

• Norikyo declared: “Shintō is the National Way (Shintō wa kokudō nari). This was not called Shintō at first, but after the importation of the doctrines of Buddhism and Confucianism the National Way came to be called Shintō…. The National Way is not something shameful and contentious, that makes trial of the gods. It is ethics and keeping one’s household in order. The operation of the government is the National Way.”

• Thus, in addition to considerable philosophical and ceremonial instruction, he batake Chikafusa, he found the central idea of Shintō in an interpretation of the imperial regalia: the necklace for mercy and benevolence, the mirror for wisdom, the sword for strength and courage—“The man of mercy is not anxious; the man of intelligence does not go astray; the man of courage has no fears.” These virtues are the foundation of imperial rule and primary in the management of the state. This is the essence of Shintō.

(3). Tsuchimikado Shintō. A form of Onyōdō, or the Doctrine of the Positive and Negative Principles, handed down in the Tsuchimikado family. In the early part of the Tokugawa era Tsuchimikado Shimpuku came out of the Suiga school and founded the Shintō called by his name. It is sometimes referred to as Abe Shintō, after the family name of the ancestors of the Tsuchimikado family. There is an unreliable tradition to the effect that the founder was Abe Seimei (d. about 1005 A.D.), a celebrated astronomer whose family for ages furnished the headship of the official diviners. The school is also sometimes called Ange Shintō, Ange being simply the Japanese abbreviation for “Abe Family.” The school emphasized the importance of proper divination for the promotion of the prosperity of the state and the peace of the land.

(4). Uden Shintō. Founded by Kamo Norikiyo (1798–1861), superintendent (shake) of the kami Kamo Shrine of Kyōto. In the latter part of the Tempō era (1830–43) he went to Yedo and founded the Uden school, one of the most maintained that Shintō set forth the principles of correct moral conduct and embraced the standards for the proper government of the land. His chief significance lay in his attempt to inject Shintō doctrine into practical human affairs. To do this he championed an allegorical interpretation of the early myths and legends.

(5). Hakke (Hakuke) Shintō. Hakke is derived from haku, understood in the ancient sense of “head” or “superior,” and ke, “family.” The reference is to the headship of the ancient Department of Shintō (Jingi Kwan), lodged for centuries in the Shirakawa family. This family furnished the ancestral line in which the teaching of this school is averred to have been handed down. Hakke Shintō flourished in the Tokugawa era under the guidance of Mori Masatane (18th century). Stress is laid on the proper observance of ritual, on propriety and etiquette in human relations, on ceremonies for the repose of the souls of the dead, and on the correct exegesis of texts. Sacred ceremonies and the practical observance of human propriety are declared to be one and the same. Hakke Shintō eventually became merged in the Renaissance Shintō of Hirata Atsutane.

19. See Tanaka, Yoshitō, Shintō Kōen (“Lectures on Shintō”), pp. 105, Tōkyō, 1923.

20. See Tanaka, op. cit., p. 107.

21. Sir Ernest Satow, “The Revival of Pure Shintau “, Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, Reprints, Vol. II (December, 1927), p. 177.

22. Satow, Op. cit., p. 197.