Religion takes form under the pressure of insistent human needs. It is shaped by certain biological and social demands expressive of man’s underlying necessity to persist, to develop and to find an ever improving adaptation to environment. A merely suggestive summary of some of the most important of these primary demands would take cognizance of the need of food, of offspring, of protection against enemies and all evil, of personal and group health, of political solidarity, of ceremonial purity, and, as the growing moral consciousness responds to more refined situations, the need of ethical reinforcement, of aesthetic satisfactions, of companionship and friendship, and of better social cooperation and control.

Undoubtedly, the greatest of all the formative factors in the early religious life of man, as indeed of all other aspects of his existence, was the need of food. This was as true of the ancient Japanese as of other peoples. The most primitive, as well as the most widespread, of the magico-religious ceremonies of the savage have to do with increasing and protecting the food supply. The prayer of man in the present is, “Give us this day our daily bread.” “The beginnings of the moral law,” says Crawley, “are based on food-tabus; religion culminates in a divine meal.”1

Jane Harrison, in her discussion of Ancient Art and Ritual, has reminded us again of the importance of the food quest in shaping primitive ceremony.

“If man the individual is to live, he must have food; if his race is to persist, he must have children. To live and to cause to live, to eat food and to beget children, these were the primary wants of man in the past, and they will be the primary wants of man in the future so long as the world lasts. Other things may be added to enrich and beautify life, but unless these wants are first satisfied, humanity itself must cease to exist. These two things, therefore, were what men sought to procure by the performance of magical rites for the regulation of the seasons …. What he realizes first and foremost is that at certain times the animals, and still more the plants, which form his food, appear, at certain others they disappear. It is these times that become the central points, the focuses of his interest and the dates of his religious festivals.”2

Food and sex have left profound influences on religious ideas and institutions, the former far more strongly than the latter, for, while offspring came to man as the issue of easily satisfied impulses, food needs were met with extreme difficulty. Mutations in the food supply have presented man with his most vivid crises and the meeting of these crises has called forth his keenest exercise of intelligence and his most elaborate ceremonies.

A particular application of these general remarks may be found in the study of the specific problem which we have set before ourselves, namely, the determination of the original nature of the great Japanese parents. The changing aspects of heaven and earth, and especially the vivid crises of seasonal change as related to the appearance and disappearance of food, have powerfully affected the origin and development of Shintō. The ground plan of Old Shintō and the real nature of the greatest of the early “ancestors” become plain in the light of such study. It is, therefore, very important that we should attempt to determine the extent to which Shintō origins show traces of the effect of seasonal change on food supply. As a method of investigation, it is necessary for us to examine certain data which have survived out of the remote past into the very present, and which can be found at some of the shrines of modern Shintō. With this as interpretative material we shall reexamine the outline of the oldest Japanese mythology.

The dominant stock of the old Yamato folk appears in history as a race of rice farmers. The agricultural interests of the rice culture in which the lives of these ancient people centered have penetrated Old Shintō deeply. Their great deities were forces and aspects of the heavens and the earth, construed, in particular, as divine givers of life and food. And even prior to the appearance of settled agriculture, attention must have fixed on the turn of the seasons as crisis points for food and life. We can find surviving, even in modern Shintō, important vestiges that reveal the keenness with which the attention of the early Japanese ancestors was directed to the changes that accompanied the coming and the going of the seasons.

We turn then to the investigation of some of the specific details of our problem. To raise rice the early farmers needed water. They needed it then no less than they do today, for without water there could be no food. It is in a search for water, then, that we may light on our first important clue. It may help us materially in our study if somewhere in the vast complex of modern Shintō we can find rain deities and rain god shrines.

We take up, then, the consideration of data obtained from certain of the shrines of contemporary Japan. The first two which we must investigate are situated far away from the contacts of ordinary life in the mountains of Nara prefecture, below the well known city of this name. Here, in mountain isolation, ideas and practices that carry us back to the very dawn of Japanese institutions have survived to the present day. The shrines are, first, the Lower Nibu Kawakami Shrine of Nibu Village, Yoshino Gun, where a god known as Kura-Okami-no-Kami is worshipped, and again, the Upper Nibu Kawakami Shrine of Kawakami Village in the same district where a deity called Taka-Okami-no-Kami is enshrined. There are reasons for regarding these two gods as originally one and the same.

In spite of remoteness the Nibu shrines have high place in the official classification, being listed as kampei taisha or government shrines of first grade. They receive offerings and supervision directly from the Imperial Household Department of Tōkyō. The visitor to the shrines will be repeatedly assured by priest and peasant alike that the kami worshipped there are remote ancestors of the race. Yet in spite of ancestral coverings, ancient associations with weather are clear and unmistakable. The local atmosphere is heavy with rain.

A document obtained in identical form at each of the shrines makes the fact of such connection doubly plain. From this we learn that at an earlier date the shrines were called “Nibu Kawa-kami Rain-chief Shrines,” and, again, simply, “Rain-chief Shrines.” The title translated Rain-chief is read Okami in the original and is written with two ideograms, one meaning rain and the other chief or head. We are thus in possession of an easy key to the understanding of the meaning of the names of the two deities, just introduced. The gods of the Nibu shrines are “Dark Rain-chief Deity” (Kura-Okami-no-Kami) and “Fierce Rain-chief Deity” (Taka-Okami-no-Kami), kura (kurai) being taken in its ordinary sense of “dark,” and taka being given the significance of takeki, “fierce” or “brave.”

A note in the text of the shrine publication which we have before us makes the functions of these two deities entirely plain. It reads:

“Taka-Okami-no-kami is also called the dragon god of mountain tops, while Kura-Okami-no-kami is called the dragon god of valleys. The two are one and the same deity. Together they preside over rain.”3

The account of the origin of the shrines which the document sets forth is equally clear as to associations with an ancient weather lore. The text reads:

“If we examine into the reason for deifications at these shrines (we learn) that in the fourth year of Hakuhō (A.D. 675) in the reign of the fortieth human Emperor, Temmu Tennō, the sacred oracle spoke, saying, ‘Erect the pillars of my dwelling in moun tain recesses where the voice of man is not heard and there let me be worshipped. If this is done, good rain will come down upon the land and long-continued rains shall be made to cease’. Whereupon, deification in these shrines and the reverent worship of the gods in these places had their beginnings.”4

The text next quotes a passage from the Shoku Nihongi presenting more evidence of a similar nature, as follows:

“In the fifth month of the seventh year of Tembyō Hōji(763 A.D.) offerings were made to all the deities of Shikinai [region round about Nara] and a black-haired horse was presented to the deities of Nibu Kawakami. This was because there was a drought.”5

Commenting on the above passage, the compiler of the record which we have under examination, says:

“Beginning with this it has been customary, in time either of drought or of long-continued rains, for these deities to receive offerings without fail. Ordinarily, in a prayer for rain, a black horse is presented, while a white horse is presented to secure cessation of rain. In latter times however bay horses have sometimes been substituted for white ones.”6

There are indications other than this going to show that in Japanese folk beliefs the black horse is associated with dark storm clouds and the white horse with the clouds of fair weather. The early connection would appear to have been a magical one, in which the presentation of a white horse was regarded as potent to drive off the dark rain clouds and to call up sympathetically clouds correspondingly white, while, similarly, a black horse was looked upon as an effective means of breaking a drought. The usage maintains itself at the Nibu shrines. In time of protracted dry weather a black horse is sometimes, even in the present, led in ceremonial procession before the altars of the deities and when the crops of the local agriculturalists are threatened by long-continued rains, a white horse is introduced in the rites.

In the early part of the fourteenth century the Emperor, Go-Daigo Tennō (1318–1333), on the eve of the Great Succession Wars, was obliged to flee to the village of Yoshino, near the Nibu shrines, and here he established the so-called Southern Court. The annals of these shrines, influenced by this unfortunate episode, preserve the following statement:

“In his temporary palace at Yoshino, at what time the early summer rains ceased not, when messengers with offerings were dispatched to the shrines of the Rain-chief to effect the stopping of the rain, the Emperor pondered and wrote:

Which may be rendered:

“This village

Is close to

Kawakami of Nibu;

If one but prays, behold, ’twill clear—

The rainy sky of early summer.”7

The document from which the preceding citations have been taken says in conclusion:

“As reverently set down above, the divine virtue of our great deities causes the falling of fresh rain in time of drought and makes long-continued rains to change to fair weather, whereby the earth is enriched and the five cereals ripened, so that herein the name of Abundant-Reed-plain-Land is not gainsaid. And as the unending flow of the Nibu river shall never cease, so also the deities that dwell here shall eternally guard this Land. There is, indeed, not a single subject of our Imperial Land who does not participate in their favors. How greatly, then, should one who is born in this land and who eats the fruits of its soil revere and honour the sacred virtues of these great deities.”8

Material such as this is not confined to the Nibu shrines. Some ten miles to the northward of the central railroad station of modern Kyōto, in a beautiful mountain setting above the Kibune river, is situated the Kibune Shrine, listed in the official shrine catalogue as kampei chūsha, or government shrine of middle grade. The exact age of the shrine is uncertain, the date of the founding being unknown to the shrine authorities themselves. The shrine annals contain a record of the rebuilding of a still more ancient structure in 677 A.D. The god worshipped here is the same Taka-Okami-no-Kami made known to us in the records of the Nibu shrines just studied, and once again the old association with rain is unmistakable. A copy of the shrine chronicle furnished by the priests in charge includes the information that this deity is the child of Izanagi-no-Mikoto and that he is widely known for “water virtue” (suitoku).

The ensuing passages translated from this document show the same intimate connection with rain and water as that already found at the Nibu shrines.

“In the time of the fifty-second human Emperor, Saga Tennō namely, in the seventh month of the ninth year of Kōnin (A.D. 818) the drought was very severe and the colour of the five cereals faded. Then the Imperial Court sent messengers and presented offerings, including a black horse, and the rites of praying for rain were carried out.

“In the sixth month of the tenth year of the same era(A.D. 819) when the rains were long-continued, the Imperial Court sent messengers with offerings, including a white horse, and rites of prayer for fair weather were carried out. In each case the favorable answer of the god was immediately revealed. Beginning with this, whenever there were drought, long-continued rains or failing crops in the land, the Imperial Court without fail sent messengers, made offerings and performed worship.

“We humans and all other things that flourish upon the surface of the earth are dependent upon the divine gift (onkei) of water. Especially in the case of the three employments that constitute the major industries of our country, namely, farming, fishing and the carrying trade, great indeed are the favours of water that are received. Accordingly, the worship of the deity who presides over this water is the means of securing assurance of food and clothing. The fact that the number of worshippers, not merely of farmers and fishermen but also of voyagers to foreign lands, has recently shown yearly increase, is due not simply to an exaltation of the spirit of reverence, but more than this to the activity of the divine virtue of the enshrined deity.

“Among the yearly ceremonies is the festival of praying for rain (amagoi saijitsu), held on the ninth day of the second month. Large numbers of worshippers then come together and at the main shrine and, also, at the interior shrine [oku-miya—a smaller shrine situated about one half mile farther up the valley] and, again, at the rain-prayer-waterfalls (amagoi daki), they pray that rain may fall in proper measure and that the five cereals may ripen abundantly. On that day at the bowl of the waterfall the following sacred song is sung, accompanied by ancient rites:

The sense being:

“That the precious rice fields

Be enriched to the full

With heavy downpour,

Let fall the rain above the water-dam,

Thou deity of Kawakami.”

A note in the text says in explanation of the last term:

“The enshrined deity has been called ‘River-Source-Deity” (Kawakami-no-kami) from ancient times because of having his seat of enshrinement at the source of the river.”10

The central rite in the water ceremony is the reading of a norito in which special supplication is made for auspicious rains. In the mountains behind the Kibune shrine are three waterfalls, situated one behind and above the other. Over these in proper season a small stream passes. The innermost of these is regarded as the very source of the water so much desired by farmers below, and here it is, close to the great heavens whence the rains come, that especially efficacious prayer is made. This is the ceremony of amagoi daki (“rain-prayer water-fall”).

Its importance as interpretative material has necessitated the presentation of the above data at some length. We have succeeded in definitely isolating certain water gods, originally rain deities, and have found that these divine beings and their shrines, from very remote times, have been the focusing points of the food interests of a race of agriculturalists. Does this material assist us in any way in arriving at a better understanding of Shintō beginnings and in particular of the original nature of the great parents, Izanagi and Izanami ?

The question can perhaps be answered if we can determine just how the intimate association between rain and the deities of the three shrines which we have been investigating has come about. If we can account for this relationship satisfactorily we may possibly find ourselves on the way to a new understanding of Old Shintō.

Who, then, are these deities of Nibu and Kibune ? Are they bona fide ancestors who have somehow acquired a control over the weather, or is some other explanation in order ? Fortunately, the mythological sections of the Kojiki and the Nihongi are sufficiently well preserved to enable us to answer our question without large room for doubt. It happens that we know exactly how and when the rain deity, Kura-Okami-no-kami, introduced above, was born. He was created by a sky father in the midst of the fury of seasonal storm that marked a crisis in the food-quest of the early Japanese ancestors. The evidence for this statement follows.

As already noted, Japanese mythology opens with a scene in Takama-ga-Hara, the High Plain of Heaven, which whatever else it may mean, was the dwelling place of the kami before the “great ancestors” came down into Japan. Some fifteen gods and goddesses (Kojiki account) are introduced in rapid succession, without episode or movement in the story itself, and then we come to the two great creative deities, Izanagi and his spouse, Izanami, with whom Japanese cosmogonic mythology may truly be said to have its beginning. Indeed, the kami preceding this pair play such minor parts in Shintō myth, history and contemporary cult life alike that it almost seems fair to conclude that they do not represent original Yamato traditions. In what must be regarded as the original account, the story centers in Izanagi and Izanami as the great parents of the race. These two come down from the High Plain of Heaven and, as the Kogoshūi informs us, “They beget the Great-Eight-Islands, also mountains, rivers, grasses and trees, and they likewise beget the sun goddess and the moon god.”11 Finally, while in the midst of this creative activity, the wife gives birth to a child of particular viciousness called Kagu-Tsuchi, who has generally been identified as an ancient fire god, but whose actual function in relation to seasonal change and food needs to be more carefully noted. In giving birth to this child the mother dies, or, as the old record says, she grows “feverish, her private parts are burned” and “she suffers change and goes away.” She withdraws to the Land of Yomi, the Japanese Hades, the Realm of Darkness beneath the upper world. The meaning of this withdrawal to the lower world must be carefully noted. We will return to the point later. The husband is left desolate on the upper earth. He mourns bitterly that he should have given his beloved wife for an evil-hearted child.

Then, as the old story continues, Izanagi rises up in anger, draws the great sword that hangs at his side and kills this evil child. It is necessary that at this point we give the wording of the Kojiki text itself, since we are now about to witness the birth of the rain god whose authentic pedigree we have set out to determine. The translation of the titles of the various deities mentioned in the narrative is postponed until we have the full account before us.

“Then Izanagi-no-Mikoto drew the ten-hand-breadth sword which he wore and cut off the head of his child, Kagu-Tsuchi-no-kami. Thereupon the blood at the point of the sword bespattered and adhered to the multitudinous rock-clusters and deities were born named Iwa-Saku-no-Kami, next Ne-Saku-no-Kami, and next Iwa-Tsutsu-no-Wo-no-Kami. Again, the blood at the upper part of the sword bespattered and adhered to the multitudinous rock-clusters and deities were born named Mika-no-Hayabi-no-Kami, next Hi-no-Hayabi-no-kami and next Take-Mikadzuchi-no-Wo-no-Kami. Another name for this last deity in Take-Futsu-no-Kami. Another name is Toyo-Futsu-no-Kami. Again the blood that gathered on the hilt of the sword came dripping out between his fingers and deities were born named Kura-Okami-no-Kami and Kura-Midzuha-no-Kami.”12

The Nihongi version adds to the two deities last mentioned the name of Kura-Yama-tsu-no-kami, thus rounding out the numbers to three groups of triplets born from the sword of Izanagi.13

It is very important that we should not go astray in our interpretation of the deities in the list just given, since they are central in reaching an understanding of the nature of the ancient human experience that lies behind the entire mythological scheme. Fortunately, we have a trustworthy key in the material already examined from the chronicles of the Nibu and Kibune shrines. With this before us for reference we may undertake the interpretation of the myth that we have just examined.

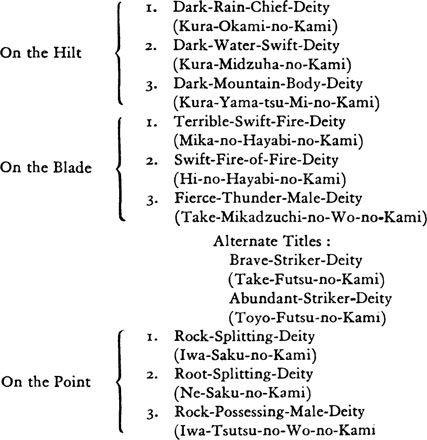

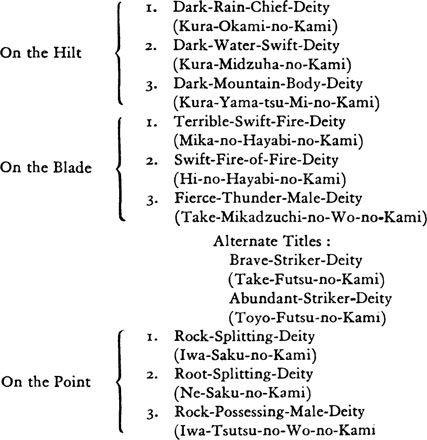

The Kojiki account presents first the three deities born on the point of Izanagi’s sword, then those born on the blade or upper part and lastly those that appear on the hilt. Reversing this order, for the sake of convenience in presentation, we have the following scheme.

Deities born on the sword of Izanagi:

In arriving at the above results the simplest and most apparent meanings of the titles have been followed. The nature of the first god that appears on the hilt of the sword, Kura-Okami-no-Kami, is too well established by the contemporary evidence already cited to admit of any possibility of error. In deriving the meaning, “Dark-Water-Swift-Deity,” for the title of the second deity, Kura-Midzuha-no-Kami, the ordinary significations of kura (kurai), “dark,” and midzu, “water,” have been adopted. Ha is taken (after Motoori) in the sense of sumiyaka, “swift.” The Nihongi informs us that a certain goddess called Midzuha-no-Me was a water deity.14 The recently published Jingi Jiten (“Dictionary of Shintō Deities”) also mentions a popular belief to the effect that she is a deity who presides over water.15 At the Oku Miya, or Inner Shrine, of Kibune Jinja, Midzuha-no-Me-no-Kami is still worshipped as a water goddess with functions similar to those of Kura-Okami-no-Kami.

The title of the third deity born on the hilt of the sword—Kura-Yama-tsu-Mi-no-Kami—may be rendered “Dark-Mountain-Body-Deity,” or “Dark-Mountain-Possessing-Deity.” Other interpretations have been advanced by Japanese scholars, but the weight of evidence is in favor of one or the other of the two meanings just given. The Shintō pantheon contains a whole group of mountain deities in whose titles the expression yama, “mountain,” persists. The Kojiki says explicitly that a certain Ōyama-tsu-Mi-no-Kami is a mountain god. There can be little doubt that an experience with dark mountains, the home of storms, or with dark, mountain-like bodies, in other words, black rain clouds, constitutes the formative influence in the myth of the birth of Kura-Yama-tsu-Mi-no-Kami on the hilt of Izanagi’s sword.

The names of the three gods born on the blade of the sword present no special difficulties. “Terrible-Swift-Fire-Deity “is the most apparent meaning of Mika-no-Hayabi-no-Kami, as is “Swift-Fire of Fire-Deity” for Hi-no-Hayabi-no-Kami. In translating the title of the third deity by “Fierce-Thunder-Male-Deity “(Take-Mikadzuchi-no-Wo-no-Kami). take is derived from takeki “bold” or “fierce,” while mikadzuchi has been taken as a variant of ikadzuchi, an old Japanese word for thunder. Sir Ernest Satow in his study of “Ancient Japanese Rituals “has already suggested that this ikadzuchi is in turn derived from ika, “great,” and tsuchi, “mallet” or “hammer,” which would make Take-Mikadzuchi-no-Wo-no-Kami a veritable Thor.16 In the alternate titles of this same god, the epithet “Striker” is made to stand as the meaning of futsu, a form which finds its modern equivalent in the words butsu and utsu, both meaning “to strike” or “to hit.” As confirmation of the interpretation here given, it may be noted that the Nihongi states that “Fierce-Thunder-Male-Deity” (Take-Mikadzuchi-no-Wo-no-Kami) is the child of “Terrible-Swift-Fire-Deity” (Mika-no-Hayabi-no-Kami), thus establishing that relationship between thunder and lightning that would appear normal in the experience of the makers of the myth.17 The same chronicle further declares that Mikadzuchi-no-Kami is the child of Itsu-no-Wo-Habari-no-Kami, the name given to the sword carried by Izanagi.18 If the conclusion regarding the nature of Izanagi’s sword to which we are coming is a correct one, the appropriateness of making it the father of thunder hardly needs to be pointed out. No shrines to the first two of the deities in this trio have been discovered in Japan up to the present.

The most well known shrine to Take-Mikadzuchi is at Kashima in the province of Hitachi. Here the original character of the god has been almost completely merged in an ancestor worship in which he has become the patron deity of valor. Yet local legend has not forgotten that he first manifested himself as a strange spirit clad in white garments and armed with a great white spear, that first appeared on the top of a mountain. Another important center of the modern worship of Take-Mikadzuchi is at Kasuga in Nara, where, again, ancestral interpretations predominate. On the mountain top above the shrine, however, the peasants of the vicinity still preserve an old thunder god sanctum (Naru-Kami Jinja) where they seek superhuman aid in securing rain in dry weather and in the protection of their crops against insects and disease.

The renderings, “Rock-Splitting-Deity “(Iwa-Saku-no-Kami), “Root-Splitting-Deity “(Ne-Saku-no-Kami) and “Rock-Possessing Male” (Iwa-Tsutsu-no-Wo-no-Kami) for the titles of the three gods born on the point of Izanagi’s sword seem clear. The story here appears to reflect a widespread belief that rocks, and in particular flints, which contain a mysterious element of fire and which reproduce the lightning flash in miniature are thrown down to earth in the thunderbolt, and that the sacred fire which falls from heaven enters “into rocks, trees, and herbage,”19 as the Nihongi itself says, whence it may be extracted by striking or by friction. No shrines to the deities in this third group have as yet been discovered in contemporary Japan.

We are now in position to summarize the data presented thus far in the present chapter. How shall we interpret a sword that at its point breaks the rocks, splits the trees to the roots and impregnates stones with fire, that appears in its blade as a swift fire giving birth to a thunder child and that brings forth at its hilt dark mountain-like masses that drip with water ? Plainly, it is the picture of a thunder-storm. Kagu-Tsuchi was killed by a mighty storm in which, when the sword of Izanagi flashed in the sky, swift fire broke on the rocks and trees, Mika-dzuchi pounded with his hammer, Kura-Yamatsu-Mi-no-Kami was seen in the form of great, black, mountain-like masses up above, and then, as the climax of the entire scene, trickling out from between the fingers of Izanagi came Kura-Okami and Midzu-Ha—water, raining down out of the black clouds upon the earth beneath. We stand here in the presence of the most sublime, and probably the most ancient picture, in early Japanese literature. It is indeed a picture-poem, certainly one of the first ever produced by the remote ancestors of the race. It contains all the elements of a terrific storm of thunder, lightning and rain, interpreted in the picturesque and powerful imagery of primitive mythology. It is an old mosaic, scattered and worn by time, but when the parts are reassembled, we see emerging from the shadowy background the likeness of a Zeus. The pathway from the modern shrines which we have followed leads us back into a remote nature cult, wherein we come into the presence of an archaic sky father, who carries a sword which is the lightning flash. The details of the picture are too orderly to have had their origin in mere mythological fancy. Nor are they simply literary devices on the part of some ancient writer or group of writers. Behind the myth is a universal human experience—the wonder and awe of man in the presence of great storm. We have only to recall the outlines of the picture to confirm this impression: at the hilt, dark rain, dark swift water and dark mountain-like clouds; on the blade, swift fire, and fierce thunder; at the point, a splitting of trees and rocks and a quickening of stones with fire.

One of the Nihongi variant accounts still further connects the death of Kagu-Tsuchi with a thunder storm by introducing the statement:

“Izanagi-no-Mikoto drew his sword and cut Kagu-Tsuchi into three pieces. One became the Thunder-god (Ikadzuchi-no-Kami), one became the Great-Mountain-Body-Deity (Ōyama-tsu-Mi-no-Kami), and one became the Fierce-Rain-Chief (Taka-Okami).”20

In regard to the original nature of the first of these deities the Nihongi text here leaves no room for doubt, inasmuch as it makes use of the ordinary ideographs for thunder-god (read, rai jin; in pure Japanese, Ikadzuchi-no-Kami). Further, there can be little question that the version of the death of Kagu-Tsuchi here given is based on one and the same formative experience as that already considered in detail above. The brief passage just noted amounts to an explicit statement that the killing of Kagu-Tsuchi saw the great sword of Izanagi laid bare in the sky, accompanied by thunder and rain and also by certain other great black objects that may be legitimately interpreted either as storm clouds or as the mountains about which the storm clouds gathered. It is difficult to see how anything other than experience with seasonal storm could have produced this mythology.

Thus the birth of Kura-Okami-no-Kami, the rain deity of the Nibu shrines, with whom our investigation began, was a rainstorm and Kura-Okami is in origin nothing other than rain, and his creator is the Great Sky, the progenitor of rain. This is only part of the story, however.

1. Crawley, A.E., Art. “Food,” Hastings Enc. Rel. and Ethics, Vol. VI, p. 59.

2. Harrison, Jane, Ancient Art and Ritual, p. 31.

3. Nibu Kawakami Jinja Ryakki (“An Outline History of the Nibu Kawakami Shrine”); no date; pub. by the shrine office.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Kibune Jinja Ryakki (“An Outline History of the Kibune Shrine”); no date; pub. by the shrine office.

10. Ibid.

11. Saeki, A., Kogoshūi Kōgi (“Lectures on the Kogoshūi”), p. 4. Published by the Kōgaku Shoin, Tōkyō, 1921, 10th ed.

12. Cf. Chamberlain, Kojiki, Transactions Asiatic Society of Japan, Vol. X, p. 32 (Supplement, 1882).

13. Aston, Nihongi, Vol. I, p. 23 (Edition of 1924).

14. Ibid, p. 21.

15. Jingi Jiten (“Dict, of Shintō Deities”), pp. 31, 249.

16. Satow, Sir Ernest, “Ancient Japanese Rituals”. Trans. As. Soc. Japan Reprints, Vol. II (Tōkyō, 1927) p. 40.

17. Aston, Nihongi, Vol. I, p. 23.

18. Op. cit., p. 68.

19. Op. cit., p. 29.

20. Op. Cit., p. 28.