Evidence in support of the conclusion that Izanagi originated in early experience with phenomena of the sky, namely, that he is a true sky father, is not confined to that which has just been studied. In 1910 Dr. Inouye Tetsujirō, the father of the scientific study of religion on the part of modern Japanese scholars, published in the Tetsugaku Zasshi (“Philosophical Journal”) an essay on Japanese mythology in which he announced that he had finally come to the conclusion that Izanagi should be taken as a personification of the sky, and Izanami, his wife, as a personification of the earth.1

He was formerly of the opinion that these deities represented Day and Night, respectively, resembling the Indian deities, Yama and Yami, but later abandoned this view. His reasons for regarding Izanagi as a representation of the sky and Izanami as a representation of the earth are twofold. In the first place, in their final places of habitation Izanagi is completely identified with the sky and Izanami with the earth. After his creative work on earth had ceased Izanagi went up to heaven to live in the Hi-no-Waka-Miya (Nihongi), which is taken to mean “The Young Palace of the Sun,” or “The Never-again Palace of the Sun.” Izanami, on the other hand, was left permanently on earth, or, rather, as queen of the lower world. In the second place, the deities created by Izanagi subsequent to his return from Hades were of such a nature as to point strongly to an original sky god character for the great father. From Izanagi’s left eye came Amaterasu-Ōmikami, the goddess of the sun, from his right eye, the moon god, Tsukiyomi-no-Mi-koto, and from his nostrils, Susa-no-Wo-no-Mikoto, the god of stormy, violent wind. Dr. Inouye makes no attempt to present more than a suggestive summary of his views. The weight of his scholarship is important, however, and his suggestions deserve further exploration, particularly his second point.

The Nihongi account of the creation of the three great deities of the upper air reads:

“When Izanagi-no-Mikoto had returned (from the Lower World), he was seized with regret, and said, ‘Having gone to Nay ! a hideous and filthy place, it is meet that I should cleanse my body from its pollutions.’ He accordingly went to the plain of Ahagi at Tachibana in Wodo in Hiuga of Tsukushi, and purified himself…. Thereafter, a Deity was produced by his washing his left eye, which was called Amaterasu-no-Oho-Kami. Then he washed his right eye, producing thereby a Deity who was called Tsukiyomi-no-Mikoto. Then he washed his nose, producing thereby a God who was called Sosa2-no-Wo-no-Mikoto. In all there were three Deities. Then Izanagi-no-Mikoto gave charge to his three children, saying, ‘Do thou, Amaterasu-no-Oho-Kami, rule the plain of High Heaven; do thou, Tsukiyomi-no-Mikoto, rule the eight-hundred-fold tides of the ocean plain; do thou, Sosa-no-wo-no-Mikoto, rule the world.’”3

So runs the old account of the origin of the great deities that head the Japanese national genealogies. It is of some interest to our discussion to note analogous details in Polynesian mythology. The account from the Cook Group relates that the father of gods and men was Vatea who took to wife Papa, the earth mother. A version which Gill considered very ancient represents Vatea as possessed of two wonderful eyes, “rarely visible at the same time.” “In general, whilst one, called by mortals the sun, is seen here in the upper world, the other eye, called by men the moon, shines in Aviki (the spirit world).”4 A Maori poem speaks of the sun and the moon as having been thrown up into the sky “as the chief eyes of Heaven.”5 Dixon says, “The sun and moon in the Maori myth seem generally to be regarded as Rangi’s offspring who were later placed for eyes in the sky, and similar beliefs prevailed in the Society Group and in Samoa.”6

A Shintō Procession

The ceremonial object borne by the attendant in the foreground is called a gohei. It is traditionally explained as a symbolic offering. It is, however, a potent purification device and frequently symbolizes the divine presence itself. The form of the gohei possibly perpetuates that of the sacred tree of Shintō.

We return to the Japanese story. It seems legitimate to conclude that a myth which connects the creation of the sun and moon with the eyes of Izanagi can mean little other than that this kami is to be understood as a deification of the sky, regarded as possessing two wonderful eyes. The account of the origin of Susa-no-Wo-no-Mikoto, the god of stormy wind, can likewise be consistently interpreted as an ancient notion that the raging, violent wind was the snorting breath of the sky father. The Nihongi says that another wind god, Shina-tsu-Hiko-no-Kami (“Prince-of-Long-Wind-Deity”), who drives away the morning mists, is the breath of Izanagi.7

In elucidating the sky father characteristics of Izanagi, it is particularly important that we study his activities in relation to those of his mate, Izanami. We may turn then to the presentation of evidence showing an original chthonian character for Izanami. The first point that we should note is the significance of the birth and death of Kagu-Tsuchi-no-Kami. Who is this strange being whose birth causes the withdrawal of his mother to the lower world and who dies in a rain storm ?

The plain and literal meaning of Kagu-Tsuchi is “Glittering Earth,” and we may take it as fairly certain that this name indicates exactly what he was in the original experience out of which the myth grew. He also goes by another name, Ho-Musubi-no-Kami (“Fire-Generating-Deity”), and in harmony with this latter appellation he has been commonly identified as a fire god. A more fundamental interpretation, which takes into consideration more exactly his place in the total mythological scheme, must find his origin in an early experience with earth in a fiery mood, that is, with an earth dried, parched and glittering, in an intense summer heat,8 all of which may say something regarding the early environment of at least a section of the Japanese people. The interpretation here advanced has confirmation in the words of the myth which tell how, at the birth of Kagu-Tsuchi, his mother “grew feverish,” how “her private parts were burned,” and how “she suffered change and went away,” which is, apparently, only a way of saying that her fecundity was impaired. In fact the old mythology, in forms that are about as plain as human words can well be made, thus sets forth man’s experiences in a climate in which vegetation withered and died owing to the coming on of a season of intense heat. It was a heat so great that it “glittered” and “shone,” a very god of fire was brought forth from the womb of mother earth. It was then that the father grew desolate, and pondered the curse that had come upon him through the birth of an evil-hearted child. We may be certain that before the great father, Izanagi, suffered, the early myth-makers themselves suffered, and that the evil which was in the heart of Kagu-Tsuchi was only a vivid projection of evil that had come to the food supply of man. And then Kagu-Tsuchi died in a great storm. He was killed by the sword of the sky father. Yet he did not altogether die. His death was the breaking of a drought. This becomes apparent in the sequel.

To make the matter clear to ourselves, we should note the significance of the death of the mother and her withdrawal to the lower world. It is manifest that this great transformation is simply a part of an ancient story of experience with drought. When Izanami lost her life-giving powers and passed from the upper world she went to the land of Yomo (or Yomi) beneath the earth, and here, according to the Kojiki, she became the “Great Deity of Hades” (Yomo-tsu-Ōkami). She thus possesses the twofold character of goddess of the upper world and queen of the lower world and in this double capacity repeats functions which the student of social origins will recognize as belonging to earth mother deities in other fields.

The story of the withdrawal of Izanami to Hades and the search for his lost wife on the part of the distracted mate has been pronounced the most striking episode in all Japanese mythology. It is indeed so—striking in its human pathos, striking for the remarkable parallels that can be found among other peoples, and most striking for its significance in the food-quest of the ancient Japanese.

Thanks to the labors of a group of American and European scholars, mainly in the European and Near Eastern fields, we are able to make comparison with a whole series of such withdrawals to the world of death, and with searchings by a distracted mother or lover: for example, the search of Isis for Osiris, of Istar for Tammuz, or Dionysos for Semele, of Demeter for Kore (Persephone), of Cybele for Attis, of Hermodr for Balder, etc. There is pretty general agreement as to what these withdrawals signify in the original creative experiences. They are mythological projections of the effect of seasonal change on vegetation. In a cold climate when winter comes on, earth’s vegetation withers and mother earth retires. In a hot climate when the heat of summer grows severe vegetation likewise languishes and withers, and the earth mother grows feverish, is burnt, and goes away. The search which the Japanese Izanagi makes for Izanami re-echoes the search of the Egyptian Isis for the body of Osiris.10 The original meaning of the death of Attis in the Phrygian myth of Attis and Cybele was the death of vegetation in winter. In regard to the Phrygian version Grant Showerman has written:

“The Cybele-Attis myth…. symbolized the relations of Mother Earth and her fruitage. Attis is the plant kingdom beloved by her: his emasculation is the cutting of her fruits: his death, his burial, and his preservation by the mourning mother symbolize the death and preservation of plant life through the cold and gloom of winter; his resurrection is the return of the warmth of spring.”11

In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter the story is told of how Persephone (Kore), when gathering flowers in the field, was stolen and carried away to the under world.12 The mother saddened and languished and refused to produce food that men might live. The earth was unfruitful. It was finally arranged that the daughter should spend eight months of each year with her mother, during which time the earth brought forth food. There are reasons for believing that the original Greek myth attributed the dearth of food on earth to the withdrawal to the lower world of the mother goddess herself. The Kore myth was probably a later development corresponding to a considerable progress in agriculture. Thus the languishing and the withdrawal of the Greek earth mother are exactly comparable with the death and departure of the Japanese earth mother.

An old Babylonian poem describes the descent of the Babylonian earth mother, Istar, into Hades (Aralu) in search of the lost Tammuz. Her way is barred by seven mighty gates, one within the other, and at each of these her garments and ornaments are stripped from her and finally she is stricken with disease. Meanwhile in the upper world there is lamentation among gods and men; the earth is desolate; vegetation withers and dies away. Only water can accomplish the release of Istar from the dark land “from which there is no return.” At last Ea sends a messenger to Aralu to demand the water of life. Water is given, and with this the body of Istar is sprinkled. Then her restoration begins. She makes her way back to the upper world, and at each of the seven gates her clothing and ornaments are returnd to her, until once more fully clothed she makes her way over the living earth.

MacCulloch from whose account the above summary is made, further remarks:

“The story, as connected with Tammuz, must have described his restoration by means of the life-giving water at the instance of Istar come in quest of him—an incident enacted in the Tammuz ritual. But this is not set forth in the poem, though there is an obscure reference to Tammuz at the end, in the form of ritual directions to mourners, to whom the poem appears to have been addressed. Pure water is to be poured out for Tammuz.”13

It was water, then, that brought about the return to the upper world of both Tammuz and Istar.

Jeremias, in his study of Babylonian religion, has interpreted the situation out of which the myth, summarized above, grew, as follows:

“Since nature dies and comes to life once more (in cosmical language, sinks into the under world and then rises again), she [Istar] is the goddess who goes with dying nature into the under world and who brings up the new life.”14

With this suggestion, it requires but little imagination even for one untrained in the lore of ancient man, to understand what intense experiences the old myth has worked into poetry when it says that the earth mother laid aside her garments and her ornaments when she entered the land of death, and that in the resurrection of herself and her child water was sprinkled upon them. The sprinkling of the water is suggestive of a rain storm. The revival of Istar and Tammuz is the breaking of a drought.

The closeness of the parallelism with the Japanese account is striking. It must be recognized, however, that the establishing of a full parallel requires, as one of its main elements, the existence, on the Japanese side, of a record of the return of the earth mother from Hades and her creation anew of agencies that have directly to do with the overcoming of drought and the reappearance of food. If Izanami-no-Kami is a true earth mother who passes through transformations corresponding to great seasonal changes in vegetation she must follow the same general course as that taken by similar deities elsewhere and complete the full death-life cycle by returning to the upper world with reviving vegetation.

Early Japanese literature has preserved for us a ritual for use in the fire-subduing ceremony, which gives every indication of being very old, wherein we find very important evidence bearing on this theme. After recounting the story of Izanaml’s death, her separation from her husband and her journey into the lower world, the pertinent section of the norito says:

When she reached the even hill of Yomi she thought and said, ‘In the upper world, ruled over by my beloved husband, I have begotten and left behind a child of evil heart.’ So, returning, she yet again gave birth to children, to the Deity of Water, Gourd, River Leaves, and Clay Mountain Lady (Hani-yama-Hime)—to these four kinds of things she gave birth. Then she taught Izanagi, saying, ‘Whenever the heart of this evil-hearted child becomes violent, subdue it with the Deity of Water, with Gourd, with Clay Mountain Lady, and with River Leaves.”15

The prominence of water in the above account deserves special attention. “River Leaves,” as one of the agents in the control of Kagu-Tsuchi, strongly suggests seasonal change, wherein the new vegetation first appears along the course of rivers. We may compare with this the Phrygian story which says that the resurrected body of the vegetation god, Attis, was found on the reedy banks of the river Gallus, and, again, with the fact that in the account of the legend by Pausanias, Attis was the child of the daughter of the river Sangarius.16 The gourd which the Japanese ritual introduces as a second agency for the control of Kagu-Tsuchi is simply a very ancient and a widely disseminated device for storing and carrying water. The deity of water appears as the climax of the entire episode, for, after all, it was only water that could accomplish the subjugation of Kagu-Tsuchi, just as water alone could revive the dead body of the Babylonian Tammuz. “Clay Mountain Lady” seems more difficult, until we learn that she is an earth goddess who when united in marriage with Kagu-Tsuchi, who is also an earth deity, as explained above, gives birth to “Young-Growth-Deity” (Waka-Musubi-no-Kami) who is the producer of the five cereals, the silkworm and the mulberry tree.17 The child of this last named deity is, in turn, the great food goddess Toyo-Uke-Hime-no-Kami,18 worshipped at Ise even to the very present as the greatest of the food deities of the entire Shintō pantheon. It is difficult again to see how this scheme could have been produced by anything other than seasonal change, expressed in a world-old picture of the return of an earth mother who dies and comes to life again, and who brings back to the upper world of living men, water, green vegetation, and food.

Thus underlying Old Shintō as perhaps its most powerful formative influence we read the story of the food crisis of the early Japanese ancestors; we catch glimpses of the vividness with which changes of season focused their attention. Running through the whole is the theme of water, and if we could actually unroll the years and step back into those ancient days, we Would surely find many a famine and many a desperate water shortage in which men died and languished just as did Izanami, their great mother.

The original chthonian nature of Izanami is further seen in the character of certain earth deities which appear in the mythology as the product of her individual creative activity. From her vomit came two deities of metal; from her excrement, two deities who presided over clay; and from her urine, a deity of growth.19 The Kojiki relates further that in her body, as she lay in the lower world, resided eight deities of thunder,20 an idea which has parallels in the myths of other races in the association of earth goddesses with thunder and subterranean noises.

In summary, we may revert to the affirmation that a most important indication of the original sky father and earth mother characters of Izanagi and Izanami is to be found in their primary creative functions with reference to the total mythological scheme of Old Shintō. They are universal parents. They produced the land, the living things of the vegetable world, and were the ancestors of gods and men. The Nihongi preserves the correct record of their proper position in the original mythology when it says: “They produced all manner of things whatsoever.21 As already pointed out, the Kogushūi opens its rendering of the Japanese cosmogonic myth with the activities of this pair. They are the first kami introduced. They occupy in the ancient Shintō world-view positions exactly similar to those filled by the sky fathers and earth mothers of other mythologies.

The interpretation of Izanagi and Izanami here adopted assigns them an importance in early human experience consistent with the exalted place which they occupy in the Shintō pantheon. For, although it is true that in that part of the mythology which reflects more clearly the dynastic and political interests of ancient Yamato culture, the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu-Ōmikami, takes precedence over all other deities, yet in the original cosmogonic myth itself, the activities of Izanagi and Izanami are primary. Aston classifies Izanagi and Izanami under the heading of deities of abstraction and regards them as “evidently creations of subsequent date to the sun goddess and other concrete deities, for whose existence they were intended to account.” Izanagi and his mate are assigned by this scholar “to that stage of religious progress in which the conception has been reached of powerful sentient beings separate from external nature.” The interpretation which Aston is thus led to accept is that they were suggested to ancient Japanese writers by the Yin-Yang philosophy, or the notion of male and female principles, of the Chinese.22

Against Aston’s view can be advanced the thoroughly concrete character of Izanagi and Izanami as revealed in the evidence already passed in review. They are not philosophical abstractions formulated to give a theoretical account of older deities. The central position which the great parents hold in the Japanese mythology makes it hardly possible that they could have been borrowed from Chinese philosophy without the entire cosmogonic scheme having likewise been taken over. With all the obvious Chinese influence in the Nihongi and the Kojiki there is no evidence of such extensive and early borrowing from China as is made necessary by Aston’s theory. Izanagi and Izanami must be taken as original Japanese deities. They are the concrete expression of primitive experiences with the phenomena of earth and sky, interpreted in terms of a social life that is still so undeveloped as to be confined almost entirely to the events of the parent-child group. This alone is proof of great antiquity.

Similar objections are to be advanced against the interpretation which overemphasizes an original phallic character for these deities.23 This theory builds to a large extent on etymological arguments. It follows Motoori in assigning to the words Izanagi and Izanami an origin in izanau, “to invite,” gi and mi being taken as the equivalents of “male” and “female” respectively; hence the meanings, “Male-who-invites” and “Female-who-invites”, i. e., invites to sexual relations.24 The naive detail with which the Kojiki enters into a description of the first creative activity of the pair lends some plausibility to the interpretation. The argument from alleged philological roots is highly precarious, however. On this basis there are various explanations of the primary meanings of the words Izanagi and Izanami, all equally sound, apparently; or perhaps, better, equally unsound. It is just as pertinent, for example, to interpret Izanagi to mean “Great-Male” and Izanami, “Great-Female” as it is to give the terms phallic associations. Other interpretations that have been advanced are “The First Male” and “The First Female,”25 also, “The Divine Male” and “The Divine Female.”26 That phallic practices have been part of the worship of the great parents is beyond question, as witnessed, for example, by the rites known to have existed up into modern times at their shrines on Mt. Tsukuba in Ibaraki Prefecture. Yet it must be insisted that an isolated phallic theory does not do justice to their dominant place in the old cosmogonic scheme. We should remember that phallicism, with an underlying relation to fertility ceremonies, has a world-wide association with earth mother cults.27 Priapus, the Greek phallic deity was the son of Aphrodite, who was originally an earth goddess.28 The Isis and Osiris cult of Egypt appears to have included phallic practices.29 Male and female fertility charms appeared in both the Arrephoria and the Thesmophoria.30 The great earth mother of the Yoruba of the west coast of Africa is also a phallic deity.31 It is entirely congruous that phallicism should be associated with the great Japanese parents, especially with Izanami in her character as universal mother.

The foregoing discussion is offered as evidence that in Izanagi is preserved the memory of an ancient Japanese sky father and in his mate, Izanami, the idea of a great earth mother. Izanagi is a being who produces the deities of the sun and of the moon from his eyes, the storm god from his nostrils, whose breath is the wind, and who carries a sword which is the lightning. He kills a drought-child with a great rain storm. In Izanami, his wife, we see a deity who possesses the double functions of an earth goddess of the upper world and queen of the lower world, whose body is associated with things that come from out of the earth such as metal, clay, water and growing crops. Her death and departure into the under world are to be understood as an ancient statement of the effects of seasonal change on vegetation. The early mythology, in spite of its existing fragmentary character, still preserves the story of her return from Hades with water and food. Finally the two are universal parents, not only the ancestors of gods and men, but also the creators of the land and the food plants that grow from out of the earth.

Such are the kami in whom modern Japanese historians still find original parents for the Imperial Family and the general populace alike. The sense in which they are to be taken as ancestors is clear. In finding the racial heads in Izanagi and Izanami the genealogists have been true to pure Japanese tradition, but at the same time they have built better than they know. The line as thus established does reach back to “immemorial ages.” We have before us, indeed, the extraordinary spectacle of a modern state attempting to strengthen its political and social fabric with a genealogical scheme that has come straight down out of a primitivity so remote as to bear the impress of a mythology that, considering its features both worldwide and ancient, was perhaps among man’s earliest attempts at a systematic world-view. The historicity of the two great ancestors who head the national genealogies as given in the textbooks for use in Japanese schools is to be estimated exactly as we estimate the historical validity of sky father and earth mother myths elsewhere. The study carries us into the field of pure mythology and not into that of history.

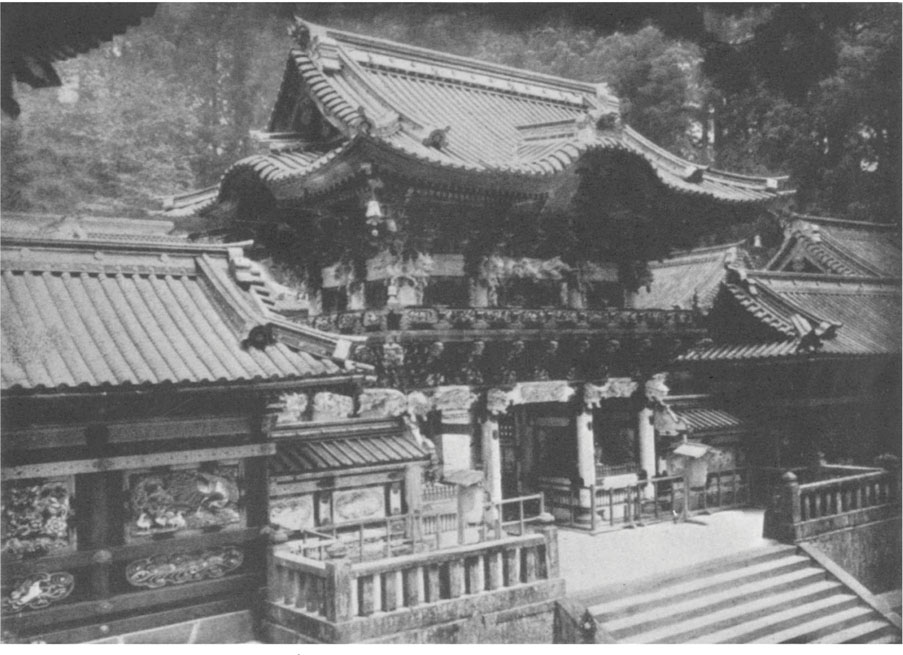

The Great Gate at Nikkō—the Yōmei Mon

In assigning the above value to Izanagi and Izanami we need not be led astray by the fact that the old literary records so fully anthropomorphize and domesticate them. Izanagi appears in the story as a patriarch who marries and begets children, who wears clothes and ornaments, and who carries a sword with which he takes the life of a child. The legend of his final place of burial on the Island of Awaji is carefully preserved.32 Izanami is represented as a woman who dies in childbirth and who is buried at Arima of Kumano.33 We should remember how folklore does the same thing for similar deities elsewhere. Greek tradition has likewise preserved the knowledge of the places of the birth and burial of the sky god, Zeus.34 E.W. Hopkins has fittingly called attention to the fact that the old Scandinavian thunder god, Thor, was not regarded merely as a noise in the sky but as “a heavenly man with a decent family of his own and with intimate relations with his clan on earth.”35 Such socialization of experience with nature is an inevitable part of the evolution of human thought. Correctly understood, it furnishes no grounds on which the euhemerizing of the mythology can be logically validated.

1. Inouye, Tetsujirō, Tetsugaku Zasshi, Vol. 25, No. 276 (1910), pp. 229 ff.

2. A variant reading of Susa-no-Wo-no-Mikoto.

3. Aston, Nihongi, I. p. 26–28.

4. Gill, Wm. Wyatt, Myths and Songs from the South Pacific (London, 1876), PP. 3–4.

5. Taylor, R., Te Ika a Maui or New Zealand and Its Inhabitants (2nd. Ed., London, 1870), p. 109.

6. Dixon, R.B., Oceanic Mythology, p. 37. See also Tregear, Maori-Polynesian Comparative Dictionary, p. 392; White, J., Ancient History of the Maori, I. p. 7.

7. “Izanagi-no-Mikoto and Izanami-no-Mikoto, having together procreated the Grcat-eight-island Land, Izanagi-no-Mikoto said: ‘ Over the country which we have produced there is naught but morning mists which shed a perfume everywhere.’ So he puffed them away with a breath, which became changed into a God, named Shina-tohc-no-Mikoto. He is also called Shina-tsu-Hiko-no-Mikoto. This is the God of the Wind.” Aston, Nihongi, Vol. I, p. 22.

8. In his commentary on “Ancient Japanese Rituals” (Norito), Sir Ernest Satow speaks of Kagu-Tsuchi-no-Kami as “the god of Summer-heat,” but makes no use of the idea as interpretative material. See Transaction of the Asiatic Society of Japan, Reprints, Vol. II (Dec, 1927), p. 37.

9. Chamberlain, Kojiki, pp. 34, 38.

10. See Muller, Egyptian Mythology(Mythology of All Races, Vol. XII), pp. 113ff.

11. Showerman, Grant, Art. “Attis,” Hastings Enc. of Rel. and Ethics, Vol. II, p. 218.

12. See Hastings Enc. Rel. and Ethics, Vol. IX, p. 78.

13. MacCulloch, J.A., Art. “Descent into Hades (Ethnic),” Hastings Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, Vol. IV, p. 650.

14. Jeremias, Allgemeine Religions-Geschichte, p. 29.

15. Ōkubo, Hatsuo, Norito Shiki Kōgi. (“Lectures on the Norito Ceremonies”), Vol. II, pp. 3–4: Ōsaka, 1908, 4th. edition.

16. Showerman, Op. cit.

17. “Upon this Kagu-Tsuċhi took to wife Hani-Yama-Hime (“Clay Mountain Lady”), and they had a child named Waka-Musubi (“Young Growth”). On the crown of this deity’s head were produced the silkworm and the mulberry tree, and in her navel the five kinds of grain [millet, rice, corn, pulse, and hemp]”. Aston, Nihongţ, Vol. I, p. 21.

18. Chamberlain, Kojiki, pp. 29–30.

19. Chamberlain, Kojikt. p. 29.

20. Op. cit., p. 36.

21. Nihon Shoki (kokushi Taikei Rokkokushi); Tōkyō, 1915, p. 13.

22. Sec Aston, Shintō, pp. 169–170.

23. See Buckley, Phallicism in Japan, pp. 22–26.

24. Consult Chamberlain, Kojiki, p. 18, note 8.

25. Sec Meiji Seitoku Kinen Gakkai Kiyō, Vol. 16, p. 125.

26. See Katō and Hoshino, Kogoshūi, p. 16.

27. See Art. “Phallism”, by E.S. Hartland, Hastings Enc. Rel. and Ethics, Vol. IX, pp. 815–31.

28. Ibid.

29. Ibid.

30. Harrison, Themis, pp. 266, 396 ff., 451 ff.

31. Hastings End. Rel. and Ethics, op. cit.

32. Sec Aston, Nihongi, Vol. I, p. 34. 33.

33. Op. cit., p. 21.

34. See Fox, W.S., Greek and Roman Mythology, pp. 143 ff; Harrison, Themis, pp. 1–15.

35. Hopkins, E.W., The History of Religions, p. 8.