An extraordinary regard for ceremonial purity runs through the entire range of Japanese history. Its importance in Old Shintō has already been pointed out.1 It strongly colours the rituals and doctrines of all the modern sects and is especially prominent in the two that we are now about to examine, Shinshū Kyō and Misogi Kyō. In its more traditional manifestations the motive of purification rests in a fear of pollution, both material and immaterial, and a dread of the frustration of happiness and prosperity caused by the malevolent spirits and evil fate that threaten to fasten their power on man whenever his uncleanness opens for them an easy entrance to the soul. In its higher reaches it becomes a passion to transcend the limitations of incomplete human selfhood and to open up an unobstructed avenue of intercommunication with the ecstatic world of spirit.

Shinshū Kyō means “Divine-learning Teaching,” a designation which is taken to signify that the doctrine and practices of the sect embody a divinely given instruction which purports to perpetuate the Sacred Way of the Old Shintō ceremonies. The “learning,” however, is not simply a body of instructions in interpretation and ritual; it involves an active effort on the human side to ascertain what the divine teaching really is. In common with practically all other Shintō societies, Shinshū Kyō also calls itself by the general appellation of Kamu-nagara-no Michi, “The Way of the Gods as Such.” It further makes use of the title, Mugon no Oshie2, the “Unspoken Teaching,” that is, the teaching which places primary emphasis on ceremonies, and in particular purification ceremonies, rather than on mere words. The teachers of the society declare that their underlying purposes are to maintain the characteristic rites and ceremonies of Old Shintō and thus to bring the immeasurable resources of the unseen world to the support of the eternal prosperity of the nation, the perpetuity of the peerless organization of the state, the securing of an abundance of crops and the guarantee of the peace of the realm. These major interests are, of course, those of Shintō as a whole. The special features of Shinshū Kyō lie in the amplification of the ceremonial means of attaining these ends.

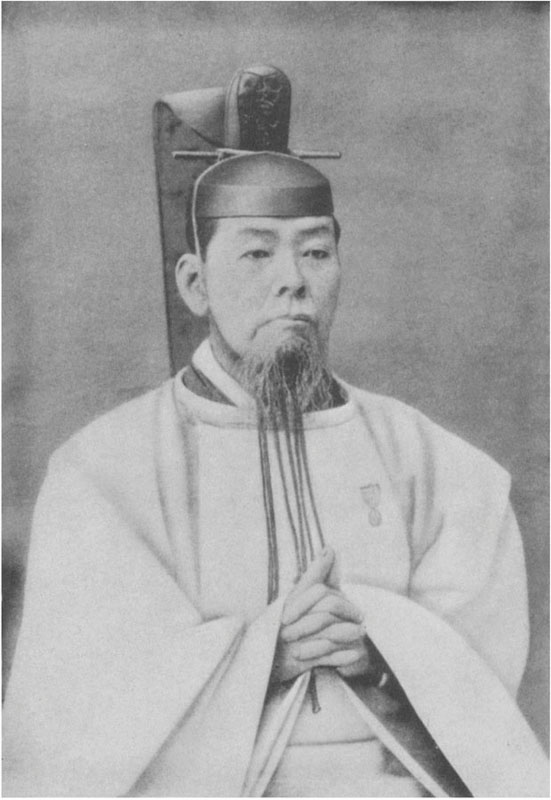

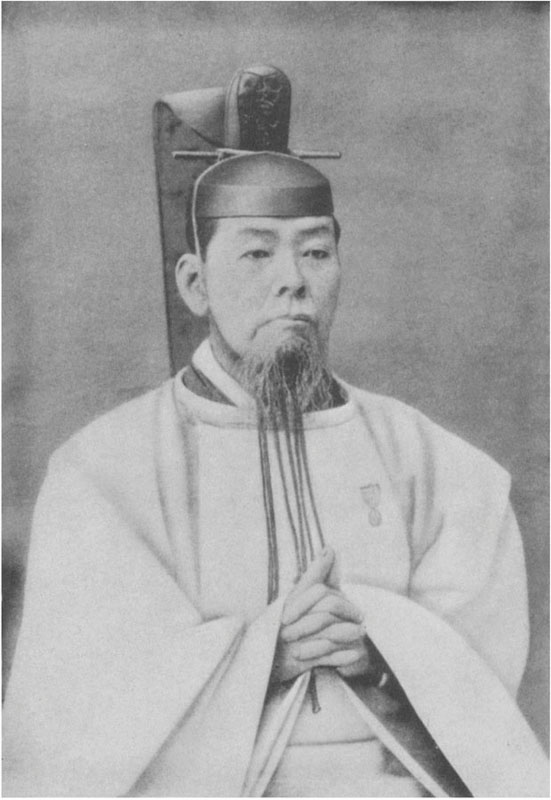

The Shinshū sect was founded by one of the Imperial loyalists of the Restoration period named Yoshimura Masamochi.3 He was born October 25, 1839, (Tempo 10. 9. 19) in the country of Mimasaka, a feudal territory which is now part of Okayama Prefecture. He studied under well known scholars and became conspicuous for his knowledge of the Chinese classics and of Japanese history and literature. Forced to flee, as a young man, before the stern measures which the Toku-gawa government adopted towards supporters of the re-establishment of the political power of the Throne, he took refuge on Mount Kurama near Kyōto. While engaged in meditation here he remembered what he had learned from his grandmother of the descent of his family from the ancient Nakatomi priesthood and resolved to devote the remainder of his life to the revival of Shintō and the restitution of the old order of the pre-Nara civilization when the Way of the Gods was completely interwoven with political life and social ethics. He forthwith prepared himself by careful study and bided his time. This did not come until after the Restoration. With the Imperial family safely restored to power and the Tokugawa authority broken, he found opportunity for the outward expression of his inner zeal for ancient national institutions. He was foremost in the movement to resuscitate the ancient Shintō shrines and uncompromising in his opposition to Buddhism. After Shintō had been reestablished as the state religion he devoted himself to three years of austerities and pilgrimages to sacred places, and then, all in a morning—so he declared—he received a revelation that he should establish a new sect. He founded Shinshū Kyō and became its first superintendent priest. Organization was consummated in 1880 and four years later the central government granted the new society authorization to set up as an independent Shintō sect.

A Priest of One of the Modern Shintō Sects—Yoshimura Masamochi, the Founder of Shinshū Kyō

For its sacred texts Shinshū Kyō turns to the Nihongi and the Kojiki as interpreted in the abundant writings of Yoshi-mura Masamochi. It attempts to find its ceremonial standards in the historical rites of the Imperial court and in the ritualistic inheritances of the Nakatomi family and thus preserve a genuine Shintō orthodoxy.

For its sacred beings it enshrines the total god-world of early Shintō and adds the spirits of all the rulers of the Imperial line. The chief divinities are the three deities of creation and growth, the sky father and the earth mother, and the sun goddess.

The founder taught that the following three precepts comprise the essential teachings of Shintō. They indicate the three stages of attainment by which the followers are taught to seek the good life: first, separation from evil, second, the strengthening of the will to attain consistent progress, and, third, union with God.

“1. To gain the gateway of goodness, strive after purity and give heed to thy soul.

“2. To gain the threshold of divine truth, apply thy heart to sacred thoughts and attain a refined spirit.

“3. To gain the dwelling place of divine truth, pacify and master thy soul and attain a nature that is divine.”4

A passage in one of the propaganda texts of the society summarizes the main discipline in these words:

“In Shinshū teaching are found: the explanation of the Way of the Gods, the doctrine of the affinity of the other world and the present world, the truth of the mutuality of deity and man, the account of the nature of the working of the divine spirit, the correction of the heart of iniquity and the return to a heart of rectitude, reverence for the spirits of ancestors, the begetting of many children, the averting of all misfortunes and the making of prayers for good fortune.”5

Practical instructions for believers are set forth in the so-called “Ten Precepts” (Kyōken Jikkajō):

“1. Worship the great deities of this sect.

“2. Pacify thy spirit, for it is a part of the spirit of deity.

“3. Practice the Way of the Gods.

“4. Revere the divine origin of the state.

“5. Be loyal to the Ruler.

“6. Be zealous in filial piety toward thy parents.

“7. Be kind to others.

“8. Be diligent in business.

“9. Preserve steadfastness within thy breast.

“10. Cleanse away the rust of thy body.”6

The theoretical foundation on which Shinshū Kyō attempts to stand is essentially that of most of the other Shintō sects, notably Shintō Honkyoku and Jikkō Kyō, as explained in preceding chapters. There exists, as the basis of all created and manifested existence an underlying, unitary, spiritual reality. This was recognized by the authors of the Old Shintō literature and by them named “The Deity Who is Lord of the Center of Heaven,” Ame-no-Minaka-Nushi-no kami. This is the absolute spiritual source of all things. He comprehends the universe and all the material objects of the phenomenal world are his “body.” In himself he is perfect and complete, omniscient and omnipotent. Folded within this primary divine Being are the potentialities of life and activity and this makes possible development and change in the world of time and space.

A mediation theory that suggests the Gnosticism of early Christian history is then brought forward to adjust this notion of an Absolute to the polytheism of Old Shintō. The capacity of the primary spiritual life of the universe for embodiment in a phenomenal world is not directly expressed, but appears only through the agency of the great gods and goddesses of ancient Japanese faith, primarily through the well-known male and female deities of growth of the Kojiki—Taka-Mimusubi-no-Kami and kami-Musubi-no-Kami—and again through the race parents, Izanagi-no-Mikoto and Izanami-no-Mikoto. From these intermediary deities come lesser divine beings, the created universe and man.

Not all the lesser divine beings are of uniform integrity, however. Some are good; some are evil. Man, by devotion to the good and by cooperation with the saving powers of the world, makes increase of the total good in the universe and assists in the overcoming of the forces of evil spirits. The reward is happiness for man in this life and a blessed existence as kami in the world beyond death.

The Great Life of the Universe thus has a particularly valid manifestation in Japanese history. The Royal Dynasty is a divine establishment and to accord reverence and obedience to the Emperor is only to recognize a divinely ordained reality in Japanese institutions.

In general the doctrine is esoteric, ceremonial and meditative. It attempts to harmonize the world of spirit which is religion with the world of material things in which are the affairs of government and social morality. Thus, devotion to earthly things is given a satisfying meaning and devotion to heavenly things is saved from vacuity. The founder taught that the true means of knowing the gods and of sharing the happiness of divine life was by participation in ceremonies and by the inner commitment of attitudes. This is what he meant by the assertion that shinshū was a “wordless teaching.” Words and letters can never express the deep realities of life. Real knowledge of religious truth comes only through the personal communion effected in sacred rite and in purified activity. In ceremony, the founder said, the worshipper is brought face to face with God in silent fellowship. This is true Shintō. Further, he declared, “If you wish to know God, you must first know your own spirit.” One’s own spirit cannot be really known until body and mind have been purged of evil. This purification is accomplished by various devices.

To this end a ceremonial life of unusual richness has been carried over from traditional Shintō. Two rites that have attracted widespread attention are the fire-walking ceremony and the hot water ordeal.

The former goes by the name of chinka shiki, or fire-subduing ritual, and the latter by the name of kugatachi shiki, or hot water ritual. The former is held at the national headquarters situated in Shinmachi of Komazawa Chō, Tōkyō, twice each year, as a spring ceremony on April ninth and an autumn ceremony on September seventeenth.

The purpose of the fire-walking ceremony is, as the name chinka shiki indicates, to subdue fire, that is, to deprive fire temporarily of its power to burn and injure. A large flat bed of glowing charcoal is prepared on the ground out of doors within the shrine precincts and when the heat has been raised to a. proper pitch the fire-spirit is placed in control of the priests by the waving of purification wands (gohei) and the recitation of rituals (norito). After the fire-spirit has been subdued the glowing coals cannot injure even those who pass directly back and forth above them with bare feet. This participation cleanses body and spirit of evil. A ceremony of recalling the fire-spirit is later performed after which the strength of the heat returns to normal and the fire burns fiercely so that one cannot endure even to go near it. If one touches the fire now he is immediately burned. All of which, according to the priestly explanation, is evidence of the efficacy of the fire-subduing ceremony.

The ideograms with which kugatachi shiki is written mean “rite of trial by hot water.” It is explained today as a ceremony of purification by boiling water rather than as an ordeal. Water is placed in an iron pot, an intense fire is prepared beneath it and when the water comes to a boil a ceremony of driving away the fire-spirit is performed by the priests, consisting in the main of waving of gohei above the pot. The participant then stirs the contents of the pot with a bunch of bamboo leaves and sprays the hot water over the body. Present-day precaution permits protection by a thin shirt. The rite is regarded as effective in purging the body of all evil. The fire-ordeal was formerly carried out on the day prior to that of the fire-walking ceremony. It is now celebrated on the thirtieth of June and again on the ninth of December of each year. It is said that in ancient times the rite was an actual ordeal. Guilt or innocence was determined by forcing the suspected person to introduce his hands into the boiling water. Liars and other evil doers were scalded while the innocent were miraculously protected.

Various other rites and ceremonies of purification are observed in Shinshū Kyō. The so-called “mystical method” which includes the two ceremonies just described, also makes use of four other important purgation devices. In the misogi hō, or “purification procedure,” cold water is poured over the naked body with the object of effecting an external purification. The founder taught that this also accomplished an inward cleansing since, when the exterior was purified, there naturally followed a driving out of the corruptions of the heart.

The batsujo hō, or “expurgation procedure,” employs rites that cleanse from inner spiritual defilement and drive away all kinds of evil in attitude and affection such as selfishness, foolishness, querulousness, anger, arrogance and all fear and delusion. The founder regarded this form of purification as involving the first principle of longevity. The method includes the recitation of a ritual of purification and the establishing of an inner reconciliation with the spirit world that transcends all the impure limitations of human selfhood and makes god and man really one.

The monoimi hō, or “abstinence method,” perpetuates ancient food taboos. This has been interpreted in the interests of a self-restraint in eating and drinking which accomplishes the purification of the blood, the control of the desires and the making over of one’s temperament so that one comes closer to the estate of divinity. “A wine drinker,” said the founder, “is full of rudeness, violence, madness and pride.” He further taught that a flesh diet tended to foster anger and cruelty and that too much eating engendered sluggishness and idleness. He fasted for periods of forty-eight days at a time and lived for years on a vegetable diet, prohibiting to himself wine, tobacco, flesh and even tea. He went without noon lunch, avoided stimulating foods and at all times ate sparingly. He found that not only was his bodily health improved and his mind made more alert, but that his original temperament and emotions were completely changed by this form of purification.

In the shinji hō, or “divine-possession procedure,” rites are observed which prevent the stagnation of the human spirit by the admission of the divine spirit into the body of the individual. The above purification methods are considered proper avenues for entrance into the Way of the Gods and may be practiced either in connection with the fire-subduing ceremony or the hot-water ordeal.7

National headquarters are situated in Komazawa, Tōkyō. Believers number seven hundred seventy-seven thousand.

The name, Misogi Kyō, is derived from the verb mi-sosogu, or misogu, meaning “to wash or to rinse with (cold) water,” or, perhaps, “to wash the body.” The total significance of the sect name is thus “Purification Teaching.” The title is expressive of the fact that the main interest of the church is to perpetuate an effective ceremonial for the purgation of body and spirit from evil and defilement.

The founder was Inouye Masakane8 (1790–1849), a native of old Yedo. His desire for sure knowledge and religious peace were stimulated at an early age by the nature of the education which he received from his father, who in turn had been deeply influenced by Buddhism, Confucianism, and the Japanese classics. On the death of his father, Masakane wandered about from place to place, seeking to satisfy his thirst for truth by sitting at the feet of various teachers and absorbing in the process a strange mixture of military training, Zen austerities, knowledge of Chinese medicine, phrenology, palmistry, purification by deep breathing, Confucian ethics, Shintō ritual, and, last but not least, much acquaintance with the world. He came under the influence of the Yuiitsu school of Shintō9 and eventually set himself up as a religious teacher. In 1840 he became a Shintō priest.

Naturally of a magnanimous disposition, he commonly shared all that he had with the poor with the result that he was frequently penniless and without means of buying food for himself. On such occasions he was wont to say, “For today the Divine Mind has decreed that I fast.” The fine breadth of his outlook on life may be gauged from his words: “Make heaven and earth your home and the firmament your storehouse. Thus you will come to know a wealth and honour that satisfy.”

Masakane was apparently a man of much independence of spirit and strong tenacity of opinion and these qualities soon brought him into conflict with the authorities. The Shogunate’s fear of his influence on the young samurai who gathered about him in large numbers led to his exile in 1843 to the island of Miyake in Izu. He spent the remaining six years of his life there, preaching to the criminals confined on the island and directing the faith of his followers at home by means of an extensive correspondence. He eventually won the respect and confidence of all who knew him. Along with other pursuits he studied and practiced medicine and is said to have healed many people of their sicknesses, partly by the stimulation of religious faith. He is said to have had power to work miracles of healing and to have caused the falling of rain in time of drought.

He looked on deep breathing as a general psychophysical therapeutic. In this matter he declared: “The myriad sicknesses arise because the spirit is disturbed and chaotic and unable to rest and because the blood does not circulate properly. For the purpose of bringing tranquillity to a disturbed and chaotic spirit, nothing excels the art of breathing. For this reason confusion of spirit can be brought under control by lowering the breath to the navel.”10

His death in 1849 left his teachings entirely unsystematized, but in the fifth year of Meiji (1872) certain of his followers organized a society called the Tōkami Kō, i.e., the “Distant-deity Band.” This later divided into two branches, one of which became merged wih the Taisei Church while the other developed into the Misogi Kyō of today. The sect received official recognition as an independent body in 1894.11

A primary purpose of the church is to perpetuate and extend the influence of the ancient doctrines regarding purification. The various rites practiced in this connection are declared to have been instituted in the mythological age by the two great kami, Izanagi-no-Mikoto and Susa-no-Wo-no-Mikoto, and handed down through the middle ages to modern times as a secret in the possession of the priestly family of Shirakawa. The sect teaches that everybody has sinned and is contaminated with defilement of both body and spirit. The one sure means of genuine cleansing is in the misogi harai or the rites of driving out impurity as practiced in Misogi Kyō. The founder often said that the greatest treasures of Japan were the three agencies of purification. These are the three sacred objects of the Imperial regalia, the sword, the mirror and the jewels which were given by the Sun Goddess to her grandson when the state was founded, and by him brought down into Japan. By the miraculous efficacy of these, all impurity may be cleansed away. Corresponding to these is the threefold magical prayer: Tōkami emitame, Harai tamai, Kiyome tamō, meaning, “Ye distant gods, smile (upon us), we pray; drive out (evil), we pray; cleanse us, we pray.” The worshipper is taught that if he chants these words with a deep earnestness which includes the purpose to commit the direction of his life to the will of the gods, he will be made joyously conscious of a thorough cleansing of both body and spirit.

The founder taught:

“There is no one who is without sin and impurity. By this (method of) purification and expulsion (of evil) this sin and impurity can be washed away. If one utters without ceasing the three-fold purification (formula) and commits his entire welfare to the divine will in absolute trust, he will be conscious of a decisive cleansing of body and soul.”12

Essential to the attainment of full inner purification and complete harmony with the divine mind is the practice of the five virtues of repentance for wrongdoing, simplicity, assiduity, gratitude and secret benevolence.

Believers pledge themselves to observe the following precepts.

“1. To remain unmoved in purpose to worship the gods and to revere the Emperor.

“2. Not to forget services of worship to the gods both morning and evening.

“3. Not to be misled by the strange religions of foreign countries.

“4. Not to be slothful in business, thereby showing gratitude to country.

“5. Not to be disobedient to the instructions of the great founder of the sect.”13

The instructions of the founder are set forth in a work of two volumes entitled “Questions and Answers” (Mondō Sho) and an additional work of six volumes called “A Collection of Final Instructions” (Ikun Shū). In these books the founder attempts to construct a satisfactory doctrine by setting up a syncretism of Shintō myth and ritual, strengthened with Buddhist metaphysics on the one side and Confucian ethics on the other. The central idea of the founder is that which has been pointed out above, an idea that is met with again and again when we penetrate to the inner beliefs of Shintō—cleansing from evil and pollution, as well as from suffering and disease, can be secured by proper rites, but only on terms of sincere trust in the goodness of the kami.

The deities of the sect are enshrined and worshipped in a series of six divisions. First comes a group of four, called the Great Creation Deities. These are the Sun Goddess (Amaterasu-Ōmikami) and the three creation deities of the Koijki (Ame-no-Minaka-Nushi-no-Kami, Taka-Mimusubi-no-Kami, and kami-Musubi-no-Kami). Next is a group of two, called the Master Gods of Purification, comprising the sky father (Izanagi-no-Kami) and the storm god (Susa-no-Wo-no-Kami). The third consists of a single deity—Ōkuni-Nushi-no-Kami, who has already been introduced as the god of the great shrine of Izumo. In Misogi Kyō he bears the title of the Ruler of the Spirit World. Next comes a group of four deities of purification who are given the collective title of Haraido-no-Kami, or Deities of the Purification-place. In the fifth division stands the tutelary deity of one’s birthplace, called the Ubusuna-no-Kami, a name that is open to several different interpretations, but which perhaps means the “deity of one’s birth-and-dwelling-place.” In Misogi Kyō this local deity, who of course varies from district to district, is always believed to preside over good and bad fortune. Finally, the spirit of the founder, Inouye Masakane, is worshipped.

National headquarters are situated in Shitaya Ku, Tōkyō. Believers are reported to the number of three hundred forty-three thousand.

1. See above, pp. 27–28.

2. Sometimes given as Fugen no Oshie, with the same meaning: “The Unspoken Teaching.”

3. Also read Yoshimura Seijō.

4. Honaga and Holtom, “The Religious and Ethical Teachings of the Modern Shintō Sects,” Christian Movement in Japan, 1924, p. 260.

5. Op. cit., p. 261.

6. Sugano, Masateru, Kyōgi no Shiori (“A Guide to the Teaching”), Intro., pp. 2–3; Tōkyō, 1928.

7. On the ceremonies see Yoshimura, Masamochi, Uchū no Seishin (“The Spirit of the Universe”), pp. 29–74; Tōkyō, 1929. (First ed., Tōkyō, 1906).

8. Also given as Inouye Masatetsu.

9. See above, pp. 37–39.

10. Uchū, Jan., 1930, p. 123.

11. Cf. Kōno, op. cit., pp. 96 ff.

12. From Jingi Jiten (“Diet, of Shintō Deities”) p. 675.

13. Tagawa, Shingi, Misogi Kyō no Kyōri (“The Doctrines of Misogi. Kyō”) in Uchū for Jan., 1930, p. 30.