The faith-healing sects of modern Shintō are Kurozumi Kyō, Konkō Kyō and Tenri Kyō. The general characteristics which these associations possess in common are: a tendency towards extreme emotionalism, a basis in revelationism, monotheistic or pantheistic trends in doctrine and a center in faith-healing. Prescriptions for the healing of sickness by means of religious attitudes and ceremonies, accompanied frequently by liberal admixture of magic, appear with more or less distinctness in some of the other sects, but in the three that we are now about to study they constitute a dominant interest.

Kurozumi Munetada, the founder of the church of modern Shintō which bears his name, was born on the twenty-sixth day of the eleventh month (lunar calendar) of the ninth year of Anei—a date that corresponds to December 21, 1780—in the village of Kami Nakano of Mitsu Gun in the old feudal territory of Bizen, an area lying along the northern shore of the Inland Sea. His birthplace now goes by the name of Ima Village of Okayama Prefecture.

The founder’s infant name was Gonkichi. Later he changed this to Sanokichi and then to Ugenji. After he had assumed the obligations of the priesthood he again changed his name to Kurozumi Sakyō Fujiwara Munetada. The last element of this rather formidable appellation is generally used today as his personal name. He was the third son of Kurozumi Muneshige and the offspring of the famous Fujiwara line. His family had furnished priests to Bizen for generations and had won the respect of the countryside for probity. The admirable character of his parents is especially mentioned in the literature of the church. His father was head of the shrine of the Sun Goddess in the founder’s birthplace. The vigorous tone of the early environment, added to the age-long traditions of the priesthood, accounts for a large share of the conditioning factors that moulded the latter’s development.

Munetada is now recognized as one of the great men of the early nineteenth century reconstruction period of modern Japan—great in an age of turmoil and strife for his sturdy simplicity, his self-abnegating devotion, his creative moral optimism and the contagious strength of his conviction that human security had its basis in an infinitude of resources in the cosmos itself—and various scholars and societies have been attracted recently to the study of his life.

A Japanese proverb says that genius is fragrant even in the bud. So it was with Munetada. From early childhood fellow villagers remarked on the deep and beautiful affection that bound him to his parents. The purpose to bring happiness and comfort to his father and mother and to honour their advancing age with his own success seems to have shaped all his acts. The will of the parent was the law of the child. Many stories are told of the extraordinary nature of his filial devotion. On one occasion when he was ten years of age he is said to have astonished his neighbors by appearing in the streets wearing a sandal on one foot and a wooden clog on the other. When questioned he explained that on being sent from home on an errand his mother had told him to wear sandals, while his father, in ignorance of this, had advised him to wear wooden clogs. He had attempted to solve the moral problem thus presented to him by obeying both as best he could.

In all his relations with the people about him he is said to have been guileless and loyal, gentle beyond the wont of ordinary children, and precociously in earnest in trying to discover the truth about life. Already at the age of fifteen he was asking how he might become a god. As a young man he attended lectures on the sacred texts of Shintō but abandoned the tutelage of the orthodox teachers when he found that they dealt only with the external aspects of so-called religion and not with the living reality itself. He regretted that nothing was said by these men about the wonderful power of the divine life, about the communion of man and god, or about the real needs of the human soul. He determined that by the contemplation and study of sacred things he would for himself try to attain inward peace and unity, that he would purify his own spirit, and gain an inner sincerity and an understanding of the mutual relations of god and man so penetrating that the divine life would entirely take possession of him and he would be transformed into a living kami. With this objective before him he became very strict in conduct and entered upon a legalistic phase of his career in which he is said to have gained a remarkable mastery over both mind and body. At this stage of his life he declared, “If I restrain myself from performing in overt act that which I know in my heart to be wrong, then I can become a kami.”1 He was about twenty years of age at the time. He had become convinced that there was no way of becoming a living god except by conduct which was itself divine. The positive implications of his conviction were far reaching; for divine conduct, he reasoned, could be nothing other than that which would bring the greatest amount of happiness to his fellow men. The mystery of death, however, baffled him; he would become a kami, but not a spirit-god in the world beyond the grave; his must be an attainment of life in the joyous world of flesh-and-blood human beings. It was not until his own feet had come almost within the portals of death, only a step removed from the other side, that a deeper enlightenment came to him.

This phase of Munetada’s inner progress is marked by three stages to which his followers have given the name of the “three worships.” The first came in connection with a great crisis which he was called upon to meet in the year 1812 when he was thirty-two years of age. On the third day of October of this year his mother died and within a week his father followed her to the grave. This brought to Munetada the greatest anguish of his entire life. So overcome was he with grief that he gave up desire to live and fell into a melancholy illness. The dreaded comsumption laid hold on him and for two years he gradually weakened on a bed of despair. Finally, on March 10, 1814, after physicians and diviners had ceased to give him hope, he resolved that the day of his death had come. He declared to himself, “If I die and become a kami, I will be able to heal the people of this world of their sicknesses.” Then as the bands of death seemed tightening about him, he performed his First Worship. This was the preparation which he made for the release of his soul from the body by first worshipping the sun, then the deities of Heaven and Earth, then his family ancestors, and lastly, the spirits of his recently departed parents. As the end drew near he gathered the members of his immediate household about him and thanked them for their care for him during his illness. Then, filled, it is said, with a feeling of great gratitude, he calmly awaited the coming of death. But instead of death a new hold on life came to him. Somewhere in the hidden depths of his being a crisis had been passed and the forces of health and optimism had won a victory. For as he lay thus on what he supposed was his death-bed, the sense of peace and thankfulness seems to have worked within him to become the occasion of his recovery.

A new perspective opened before him and he now declared to himself:

“By grieving over the death of my father and mother I have injured my spirit. I have nourished melancholy and have made myself ill. If I change my spirit and foster attitudes of happiness and interest in life, if only I make my heart cheerful, my sickness can of itself be healed. I have received this body as a legacy from my parents and to bring suffering to it is the height of unfilialness. I must now strive for the positive development of my attitudes. This is true filial piety.”2

From then on he began to direct his emotions toward a new center in gratitude and happiness and with unwonted vigour of mind set himself to fostering cheerfulness. Gradually the weight of his sickness lifted from him.

His Second Worship was on May 6, 1814. On this day he crawled out of his sick-bed, insisted on taking a bath and went out into his garden and worshipped the sun. He was persuaded that he had experienced therein a powerful renewal of health and was now convinced that his complete healing was certain.

December 22, 1814, was the day following the thirty-fourth anniversary of Munetada’s birth; it also marked the beginning of a new era in his life. On this day as he prayed before the rising sun he became irresistibly convinced that he had received from the Sun Goddess a sacred commission to share his new life with others. He declared that he was then filled with a high ecstacy such as he had never known before. He felt his mind bathed with a flood of new insight, as if he had suddenly been recreated by the Great Spirit of the Universe. This was his Third Worship.

By the believers of Kurozumi Kyō this significant experience of their great teacher is called temmei jikiju, “the direct reception of the command of Heaven,” and from this day they reckon that the career of Munetada as a religious teacher had its beginning. Before this he had won local fame for his strict piety and his impartial goodness; now he became a zealous religionist, desirous above all things else that others should share in the healing companionship of the Greater Life which he had entered and which had entered him. From now onward for thirty-six years he was the radiant apostle of the gospel of cheerfulness, health and gratitude. Like Paul on the Damascus road, he had learned out of profound suffering that unification of the inner life came not out of meticulous observance of outward precepts but by a spontaneous intercommunication with the unseen sources of health and happiness that were eternal and divine. It is said that Munetada frequently performed miracles, that he healed the sick, even those afflicted with leprosy, that he opened the eyes of the blind, and stilled the waves of the sea.

Munetada called the divine power which he believed had taken possession of him by the name which he had learned to give to the Sun Goddess of Old Shintō—Amaterasu-Ōmikami. His underlying conception of the world may, perhaps, not incorrectly be called solar pantheism. It is a belief in the objective existence of a universal, all-inclusive Parent Spirit of the universe, the source of all things, the sustaining providence which upholds and guides all phenomena, the impartial benevolence which fills heaven and earth. This universal, divine life has manifested itself in many forms, including the traditional gods and goddesses, the ancestral spirits, the rulers of the Imperial line, and in particular has found embodiment in the beneficent sun-being. The founder’s construction of doctrine in respect to the deity last mentioned was facilitated by his naive astronomy in which he seems to have regarded the sun as having a sentient, personal existence.

As the years passed the number of those who found refuge in Munetada’s teachings gradually increased. Many of his earlier followers came from the samurai class of the Okayama clan and the stalwart support which they gave him made it possible for him to propagate his faith without great opposition or fear of persecution. His influence widened and deepened with the passing years. He died on April 7, 1850.3 Twelve years later a shrine dedicated to his spirit was built on Kagura Hill in the eastern suburbs of Kyōto. This sanctuary was honoured with the recognition of special messengers sent to worship on behalf of the Emperor and the teachings of Kurozumi became fashionable even among the court nobles.

The respect thus induced in high places stood the new church in good stead during the troubled times of the opening years of the Meiji Restoration. Kurozumi’s followers received comparatively liberal treatment at the hands of the new Imperial government. In 1872 official permission was given them to propagate their doctrines with public sermons and lectures and the name of Kurozumi Association (Kurozumi Kōsha) was approved by the authorities. On October 23, 1876, they were permitted to reorganize as an independent body with the name of Kurozumi Kyōha, or the Kurozumi Sect. Later, that is, on December 16, 1882, the name of the organization was changed again to the present designation of Kurozumi Kyō.

It was one of Munetada’s principles to do the minimum of writing, consequently he left behind no systematic exposition of his thought composed directly by his own hands. Yet there are extant many letters which he wrote to his followers and friends and, also, numerous poems, sermons and miscellaneous observations which his disciples have preserved. These have been published as the sacred scriptures of the church.4

The deities worshipped in Kurozumi Kyō are Amaterasu-Ōmikami and the manifold manifestations of this all-inclusive being In the “eight hundred myriads” of gods and goddesses of Shintō. The spirit of the founder is also enshrined as a kami. As already pointed out, Amaterasu-Ōmikami is regarded as the source of all life and the creator of the universe, the unlimited and absolute God whose sustaining spirit fills heaven and earth. All events are the expression of her activity, all things of life are nourished in her light and health. Through the benevolence and power of this great deity the individual may participate in the vitality of the Absolute God and gain thereby security and the enjoyment of the blessings of goodness, truth, beauty and freedom from sickness. The propaganda tracts of the sect declare that all the philosophies and faiths of the world finally come back to this fundamental tenet. The Great Parent is manifested in the external world as the activities and principles of nature and in human society as the moral law. Thus the World-spirit reveals itself as Truth and this Truth is the underlying principle of the universe. In Japanese historical manifestation this deity has a particular national and political significance as the head of the Imperial line.

The fact that their world-view is rooted in pantheistic soil has made it possible for Kurozumi Kyō believers to maintain that their primary god-idea is monistic. The soul of man is an integration, or “Separated-part” (Bun-shin), of the Great Spirit of Life and thus, by nature, partakes of the essence of divinity and immortality. Everlasting life (ikidōshi) on the plane of oneness with the Great Parent is, however, not something that is possessed regardless of the moral quality of the individual life. Mutuality with God has an ethical basis in human attitudes and conduct. It is selfishness that impairs and destroys the measure of the realization of the divine in the human. Oneness with God is attained by a recognition of the essential divinity of all life, by a way of thought and conduct wherein personal desire and self are renunciated and the individual will is opened in utmost sincerity to the full control of the divine spirit over mind and body. Kurozumi said, “When in the heart there is nought that makes the heart ashamed, then, this is God.” Happiness and health, transcending the illusions of evil and sickness, are the immediate rewards of this unification.

These general observations are given concrete formulation in various teachings of the founder. The following translations of selected passages, though presented here only by way of illustration, may perhaps suffice to reveal the high quality of much of this material:

“When the Heart of Amaterasu-Ōmikami and the heart of man are one, this is eternal life.” I, 4.5

“When the Heart of Amaterasu-Ōmikami and our hearts are undivided, then there is no such thing as death.” I, 194.

“When we realize that all things are the activity of Heaven, then we know neither pain nor care.” I, 214.

“Forsake flesh and self and will, and cling to the One Truth of Heaven and Earth.” I, 277; II, 21.

“When one knows the power (toku) of Amaterasu-Ōmikami, then whether one sleeps or whether one wakes, how joyful one is.” I, 6.

“Happy is the man who cultivates the things that are hidden (naki-mono) and lets the things that are apparent (ara-mono) take care of themselves.” I, 158.

“Of a truth there is no such thing as sickness.” I, 147.

“If you foster a spirit that regards both good and evil as blessings then the body spontaneously becomes healthy.” I, 166.

“In truth the Way is easy. He who abandons self-knowledge and spends his days in thankfulness grows neither old nor weary. He knows only joy and happiness.” I, 211.

“Oh the joy of those who take as their guide the teaching of the Way of the Gods; for them there is neither youth nor age.” I, 20.

“True selfhood is found in that which seems to be and is not. Wander not in the non-existent; let the heart be in the unseen.” I, 21.

“Both heaven and hell come from one’s own heart. Oh the sadness of wandering in the devil’s prayers.” I, 39.

“If in one’s heart one is kami, then one becomes a kami; if in one’s heart one is Buddha, then one becomes a Buddha; if in one’s heart one is a serpent, then one becomes a serpent.” I, 147.

“If the heart is open, then there is no such thing as pain. Thus one will find only happiness and thankfulness in all things.” I, 192.

“Both happiness and suffering come from the heart—the world will be what you make it.” I, 42.

“There is nothing in all the world so interesting as error, for without error there would be no happiness.” I, 47.

“One should make the separated-spirit (bun-shin) of Ama-terasu-Ōmikami [i.e., the human soul] full and not lacking. When the spirit of cheerfulness is weakened, then the spirit of depression prevails. Where the spirit of depression prevails, there is defilement. Defilement is a withering of the spirit (kegare wa ki-kare ni te). It dries up the Spirit of Light.” I, 199.

The intensity of Kurozumi’s desire to share with his fellow humans the great good which he, himself, had experienced may be judged from his words:

“Oh how I long to make known quickly to all the people of the world the great power of Amaterasu-Ōmikami.” I, 6.

Kurozumi’s teachings regarding the brotherhood of man suggest the universalism of Stoic philosophy. All men have their origin and true home in the Great Spirit of the Universe (Amaterasu-Ōmikami). A divine sincerity fills the world and constitutes the essential nature of man. Thus, since God and man are inseparable, it follows that the individual man and his human society are not two, but one and indivisible.

Kurozumi said:

“Nothing in all the world calls forth such gratitude as sincerity. Through oneness in sincerity the men of the four seas are brothers.”6

“All men (lit. all within the four seas) are brothers. All receive the blessings of the same Heaven. The suffering of others is my suffering; the good of others is my good.”7

Referring to the fable of the two-headed bird of India, he said:

“One head was strong and the other was weak. Whenever the weak head obtained food and was about to eat it, the strong one always stole it and thus the weak one never once had food. Then one day the weak head rose up in wrath, laid hold on some poison and made as if to eat it. Then the strong head stole this as before and ate it and immediately died. Then the weak head, since it was of one body with the other, also immediately died.”8

Thus the founder illustrated his conception of the moral unity of the human race: that the good of one is the good of all and the suffering of one is the suffering of all.

Seven special admonitions of the founder are observed as practical rules for everyday living. They are set forth as attitudes or conditions to be avoided. Translated they read:

“1. That one born in the Land of the Gods should be even without faith.”

“2. That one should give way to anger or become worried about things.”

“3. That one should grow puffed up and should look down on others.”

“4. That by looking on the evil of others one should in crease within himself a heart of evil.”

“5. That one should neglect his work in time of health.”

“6. That one who has entered upon the Way of Sincerity should lack sincerity in his own heart.”

“7. That one should fail to find daily occasion for gratitude.”9

Of even greater importance, perhaps, than these in setting forth the cardinal precepts of the sect are the so-called Five Teachings (Oshie no Goji). While in their existing literary form they are not directly traceable to the hand of Munetada, being the work of Hoshijima Ryōhei, one of his immediate disciples, they are accepted today as essentially in the spirit of the great master. Translated they read:

“1. Loosen not thy hold on sincerity (Makoto wo torihazusu na).”

“2. Commit thyself to heaven (Ten ni makase yo).”

“3. Separate thyself from self (Ware wo hanare yo).”

“4. Be joyful (Yōki ni nare).”

“5. Lay hold on Living Being (Iki mono wo torae yo).”10

The members of the Kurozumi Kyō Church call themselves “fellow travelers (michizure).” They are banded together under oath to follow in the steps of the founder and not to be negligent in their obedience to the discipline. Their devotional activities include early rising, sun-bathing, deep breathing, exercises for strengthening the vital organs and the cultivation of attitudes which nourish vigour and cheerfulness of spirit.

Constructive teachings such as the healing of sickness by sincere attitudes of faith, the surmounting of misfortune by the negation of evil and the cultivation of the joy and health of oneness with the Infinite are compromised to no small measure in actual practice by accommodation to prevailing superstition in the masses. Thus genuine faith healing is supplemented by methods that make use of hypnotism, the magical transfer of therapeutic energy to the affected parts by rubbing, the recitation of purification rituals, the drinking of “god-water” (i. e., water imbued with kami-power by consecration at the shrines), the ejection of “god-water” from the mouth upon the person seeking relief, breathing the spirit of healing upon the patient, or treating in like manner the name of the patient written on a strip of paper.12

Recent years have revealed a respectable amount of attention to educational and social welfare activities. The Kansai Middle School situated at Ishii Mura of Gotsu Gun, Okayama Prefecture, is associated with the Kurozumi Kyō Church. Propaganda is carried on by means of motion pictures, also by extensive literary activities and by instruction in sermons and lectures for which not only the ordinary equipments of church and chapel are employed, but also the homes of the believers. The sect reports a total membership of five hundred sixty-three thousand. The national headquarters are situated in the suburbs of Okayama City.

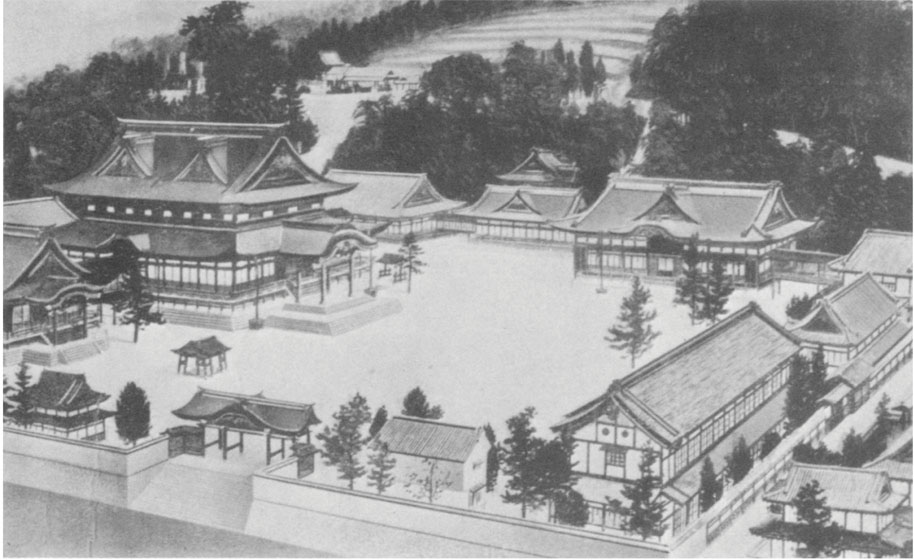

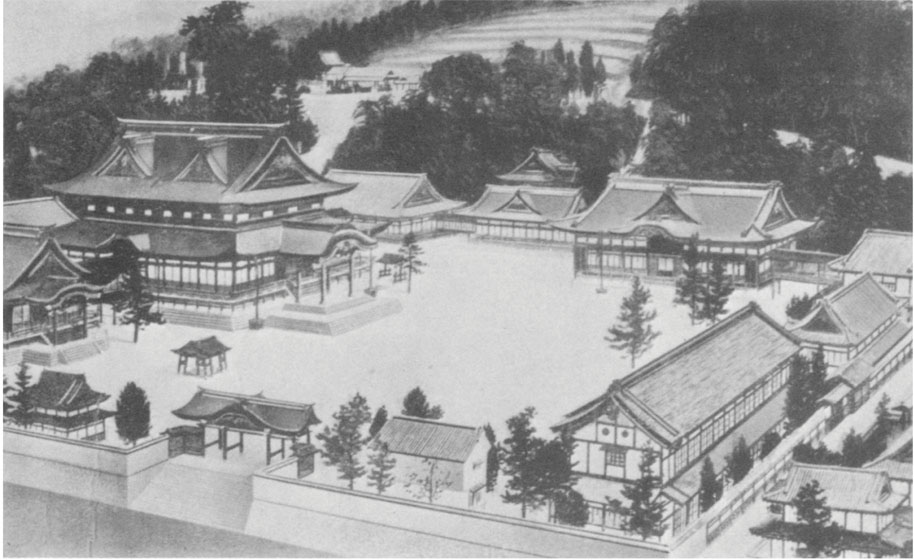

The National Headquarters of Konko Kyo

1. Kiyama Kumajirō, Ijin Kurozumi Munetada (“The Great Man, Kurozumi Munetada”), p. 2; Tōkyō, 1909.

2. Kiyama, op. cit., p. 4.

3. Kael 3, 2. 25.

4. See Kurozumi Kyō Kyōsho (“The Texts of Kurozumi Kyo”), Vols. I and II. Pub. by the Sect Headquarters, Okayama, 1914.

5. References are to the two volumes of Kurozumi Kyōsho (“The Texts of Kurozumi Kyō”).

6. Kiyama, Op. cit., p. 72.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Kiyama, Op. cit., p. 15.

10. Hayata, Gendō, Kurozumi Kyōso to Sono Shūkyō (“Kurozumi, the Founder and His Religion”), Okayama, 1930, p. 53.

12. See Hepner, C. W., The Kurozumi Sect of Shintō (Tōkyō, 1935), pp. 177–181.