Among all the thirteen sects of modern Shintō, Konkō Kyō has traveled the farthest along the way of the attainment of a free and unified faith, unbound by the restrictions of traditional ceremony and superstition. It repudiates the entire panoply of popular magic and official ritual, rests everything in the creative power of the regenerated attitudes of its believers and teaches that genuine worship must find its inevitable object in the One True God who loves those who trust him in some such way as good parents love their children.1

Some of the tenets of Konkō Kyō are so close to those of Christianity that, at first glance, one might be tempted to suspect a connection, but no evidence of any fundamental influence of the latter on the former has as yet been adequately demonstrated. Rather say that both alike arose as the inspiration of rare human spirits keenly sensitive to life’s deepest needs. The farmer-saint who founded Konkō Kyō declared that his teachings were given to him by revelation from the divine source of all truth. His followers insist that their church is built on the independent experience of their great teacher.

This experience is reflected in the history of the name by which their church is called as well as in the evolution of its designation for God. The ideograms with which the title of the sect is written literally mean “Metal Luster Teaching,” or “Money Luster Teaching,” or, again, since gold is the chief of all metals, “Gold Luster Teaching.” But all of these possible translations are misleading as to the real interests which the church pursues. The significance of the name which Konkō Kyō bears can best be discovered by following the inner development of Kawate Bunjiro2, the founder of the sect. Only a brief outline is possible here. Kawate was born September 29, 18143, the second son of peasant parents living in the village of Urami near the Inland Sea in the feudal district of Kibi, a territory which is now incorporated as part of Okayama Prefecture. He was adopted at an early age into a farmer family of the neighboring village of Ōtani. This latter place, grown to the size of a small city and given the name of Konkō, thrives today as the national headquarters of the church which he created.

The records of the sect picture Bunjirō as a sensitive, retiring child, strangely alert to the need of helping others, who spent much time either busied with his own thoughts or visiting at shrines and temples and communing with the priests. As a young man and throughout his early years as husband and father he appears as an example of domestic kindness and patient thrift, yet ever oppressed by a sense of maladjustment to the spirit world in which he so profoundly believed. His excessive devotion to the jots and tittles of religious ceremony won for him among his neighbors the nickname of Shinj in Bun4—“Pious Peter.” At this time, his life, like the lives of those about him, was made bewilderingly difficult and full of apprehension by a maze of beliefs in lucky and unlucky days, in good and bad directions, in favourable and unfavourable auspices for all the endless details of household activity, in the strange potencies of the five natural elements, in occult astrological influences, in curses by evil spirits, in possessions by foxes and badgers, in the mysterious powers of a confused host of superhuman beings, good and bad. Along with all the rest of the countryside he especially dreaded the curse of a certain calendar god named Konjin, a semi-demonic being who had been created originally in the superstitious folkways of China but who had found a congenial atmosphere in the fear and credulity of the Japanese peasants. So it was, then, that when loss of property, sickness and death among his children and other immediate relatives and, finally, a severe illness that threatened death to himself were visited upon him, his fears grew to the despaired conviction that he was being singled out by Konjin for dire punishment.

As Bunjirō lay waiting for death, his brother-in-law who had been faithful beyond all others in ministrations at his bedside, was seized with a god-possession and through him a revelation was received from the other world which announced that Bunjirō had not displeased the gods and that his recovery was assured. By this Bunjirō was convinced that some power in the spirit world was trying to do him good. The revelation took place on the evening of June 13, 18555. It marked the beginning of Bunjirō’s entrance into a unified moral world. It was only a little light that he saw at the time, shining as it were far off in the midst of much darkness, but as he followed it, it widened before him into a clear flood of insight in which he saw all things in a new relationship. At first he seems to have thought that the calendar god Konjin was being revealed to him and that he had formerly misunderstood the real nature of this god. But as a succession of revelations—now made to Bunjirō directly—brought better perspective to his inner vision, he became convinced that he was being used as a medium of communication between man and the One True God of Heaven and Earth, furthermore, that God had no evil in his character but, on the other hand, was possessed of an unlimited love toward those that trusted him and, finally, that God and man became indissolubly united when man became really sincere toward God, an experience which he called the mutuality of God and man. In the end Bunjirō repudiated all the superstitions that had troubled his earlier years, gave up his property and retired to a little hut which he built at the foot of a mountain near Ōtani. He called his hut “The Sacred Business-place of God” and for twenty-five years lived there in fellowship with his new business partner, ministering to all who came to him. He died in the early morning of October 10, 1883. The date is commemorated annually in the great autumn festival of Konkō Kyō.6

In finding a proper designation for his supreme object of worship Bunjirō took the first element in the name of the old curse-god, Konjin, and gave to it the reading kane (kon in the sea name). It was true that this might be misunderstood by some in the sense of the ordinary word for metal, but with Bunjirō it carried the idea of a totally different term, namely, kane, or kaneru, meaning “to unite.” God was the eternal spirit who comprehended and united all things in heaven and on earth. As his own experience deepened Bunjirō used various names for God. His final name, the one which has been generally adopted by his church, was Tenchi Kane no kami, “The God Who Gives Unity to Heaven and Earth.” It was a unity which had first come to Bunjirō in his own moral world, but this unity, he believed, was only an aspect of the greater moral and spiritual unity of the entire universe.

Against the background of this brief outline of the inner development of the founder we are prepared to attempt a translation of the title, Konkō Kyō. Kyō is “teaching”; kō is “light” or “glory”; kon has just been explained. Probably the best we can. do for the sect name is to translate it: “The Teaching of the Glory of the Unifying God.”

Konkō Kyō believers date the establishment of their church from the setting up of the Sacred Business-place of God by Kawate Bunjirō in the late autumn of 1859. Legal organization was not effected, however, until 1885, two years after the founder’s death. At this time Konkō Kyō was attached to Shintō Honkyoku as a subsect. Full independence was secured beginning with June 16, 1900. Today the church reports a total membership of nearly one million one hundred thousand adherents.

Sacred scriptures consist of four texts of brief, but none the less profound and sagacious, observations attributed to the founder. Bunjirō was an unlettered farmer who wrote no books and left behind no published discourses. He taught mainly by oral precept and vigorous example. The gist of his teaching has survived in certain documents, the main contents of which he dictated to his closest followers shortly before his death. They consist of “Sacred Admonitions for Direction in the True Way” (Shinkai Makoto no Michi no Kokoroe) in twelve articles, “An outline of Instructions in the Way” (Michi-no-Oshie no Taiko) in twenty articles, and “Directions Regarding Faith” (Shinjin no Kokoroe) in fifty articles. To these should be added “The Understanding” (Gorikai) consisting of one hundred paragraphs in exposition of the faith, attributed to Kawate and gathered together after his death by various early disciples. These one hundred and eighty-two precepts, admonitions and paragraphs constitute the entire sacred scripture of the church.7

The following scattered selections from these teachings may suffice to furnish a glimpse into the mind and faith of the founder.

“God is the Great Parent of your real self. Faith is just like filial obedience to your parents.

“Free yourself from doubt. Open and behold the great broad Way of Truth. You will find your life quickened in the midst of the goodness of God.

“With God there is neither day nor night, neither far nor near. Pray to him straightforwardly and with a heart of faith.

“If you lean on a staff of metal it will bend, and wood and bamboo will break, but if you take God for your staff all will be easy.

“God has no voice and his form is unseen. If you start to doubt then doubt has no end. Free yourself from fearful doubt.

“With sincerity there is no such thing as failure. When failure to accomplish your purpose in prayer arises then know that something is lacking in sincerity.

“Bring not suffering upon yourself by indulgence in selfishness.

“If you would enter the Way of Truth, first of all drive away the clouds of doubt from your heart.

“One who would walk in the Way of Truth must close the eyes of the flesh and open the eyes of the spirit.

“Put away your passions and your greed and learn the True Way.

“Do not worry, but believe in God.

“In all the world there is no such thing as a stranger.

“By your own attitudes you can bring yourself life or you can bring yourself death.

“Your body is not for your own freedom.

“Whether or not you receive spiritual power in prayer depends on your own sincerity.

“Do not bring bitterness to your own heart by anger at the things that are past.

“Do not profess love with your lips while you harbour hatred in your heart.

“God is the keeper of heaven and earth: separation from him is impossible.

“The believer should have a faith which makes him a friend of God. He should not have a faith which makes him afraid of God. Come near to God.

“(Sacred admonition) One should not speak sincerity with his mouth and lack sincerity in his heart.

“(Sacred admonition) One should not be mindful of suffering in his own life and unmindful of suffering in the lives of others.”

Konkō Kyō accepts the faith of the founder as its guide in formulating its conception of the nature of God. The following brief statement summarizes an exposition of this central phase of doctrine recently made by Konkō Iekuni, the present superintendent priest.

Tenchi-Kane-no-Kami (“The God Who Gives Unity to Heaven and Earth”) is the name ascribed to the Great Parent Spirit of the Universe who existed before all time, without beginning and and without end. He fills all things and contains all things. The manifest universe, with its infinite variety of form and event, is the outward appearance of the boundless power and goodness of this Great Being. The coming of life into this visible world, the preservation of life in this world, the coming of death and the passing of spirit into the beyond, all the details of food and shelter—not one thing, great or small, exists or is manifested apart from Him. He is the Great Parent of the true soul of man, and all men, without respect of race or country, wealth or poverty, high or low estate, have unity and brotherhood in Him.8

We have had earlier occasion to note that the pantheism which here comes to such clear expression undergirds Shintō like a fundamental rock. Certain Japanese students of Konkō Kyō have called attention, however, to what looks like a trinitarianism in the god-idea of the church. Expositions can be found in which the great pantheistic source of universal phenomena is given a threefold formulation in conceptions called respectively “The Great Sun Deity” (Hi-no-Ōtnikami), “The Great Moon Deity” (Tsuki-no-Ōmikami), and “The Great Earth (Metal) Deity” (Kane-no-Ōmikami). In this form of explanation the deities of sun and moon are understood to stand for the heavenly or spiritual attributes of the Absolute, while the concept of earth deity expresses his physical manifestations as revealed to human senses. The teachers of Konkō Kyō, themselves, make practically no use of this tri-theism, however. They point out that it had its origin in a stipulation made by the central government in the early part of the Meiji era to the effect that if the sect was to receive official recognition as Shintō, it must present Shintō gods. The name of the Great Parent God of Konkō Kyō does not occur in the classical Shintō documents. A trinitarianism in terms of the gods of sun, moon, and earth was thereupon arranged for as a formal adaptation to this requirement. The real teaching posits a fundamental spiritual unity beneath all and in all the appearances and change of the world.9

The extent of freedom from traditionalism which Konkō Kyō has attained is registered in its doctrine and practice of prayer. In the teaching of the founder, sincere prayer is the first means of fellowship with God. All spiritual communion to be effective must be spontaneous and natural. The formal, ritualistic, repetitious recitation of words and formulae, the endless mumblings and readings and ringing of bells, so widely current in the popular worship, are completely abandoned. No fixed procedure is stipulated. The one and only condition which must be met by all who would draw near to God is the inner attitude of absolute trust. The words used should be whatever are natural to the immediate feelings and needs of the worshipper. The believer should talk to God as a confiding child talks to its parents. The founder said:

“No matter how thankfully one may read his rituals and make his purifications, if there is no sincerity within the heart, it is the same as lying to God. The vain making of a big noise by the clapping of hands avails nothing, for even a little sound is heard by God. It is not necessary to speak in a loud voice or to practice intonations in prayer. Pray just as if you were talking to another human being.”10

He further said that whether or not the voice of prayer reaches through to God depends altogether on the attitude of the one who makes the prayer, for God on his part is always open to fellowship and waiting to impart Himself. When the attitude is sincere, it matters not where the prayer is made. It may be before the altars of the church, it may be in one’s room or at one’s place of work. God immediately responds to sincerity with his power and goodness and this is the true source of inner peace. This sincerity of trust is the most potent means of healing sickness and is the basis of permanent health.

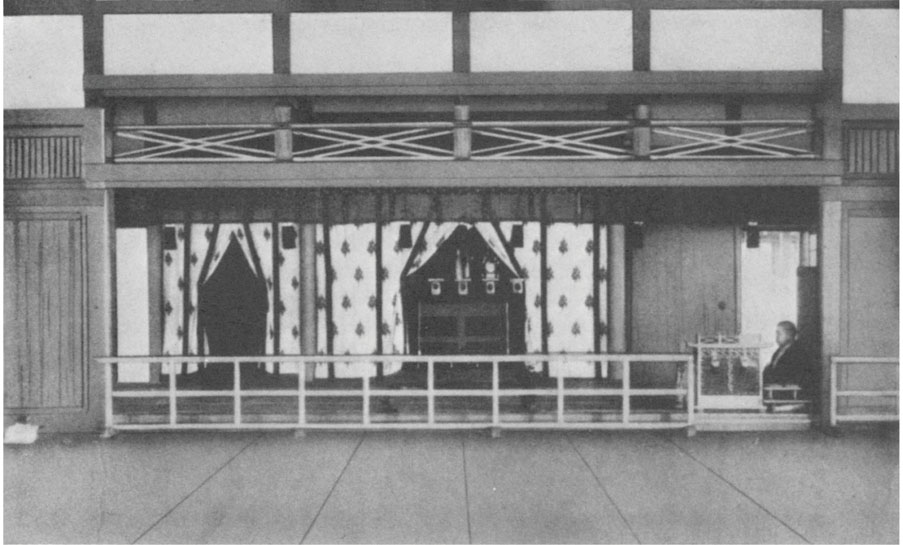

The Altars of a Church of Konkō Kyō

In this free way of the spirit penance and ascetic practices of all sorts, all reliance on the magic of charms and divination, become unnecessary. All abstinence from tea, salt, flesh, and foods cooked with fire, all fastings, all rigours such as the cold water austerities, etc., are immediately transcended once and for all. The founder said, “Rather than outward austerities, practice the austerities of the heart.” He also said, “Rather than practicing religious austerities, be diligent in your business.” By far the most important thing is a clear conscience. The austerity which the believer is taught to observe is “to polish the inner jewel of the conscience until it shines with a godlike purity.”

Konkō Kyō declares that all men are brothers. This universalism is fundamental and appears in the church’s underlying conception of religion. A propaganda booklet recently issued says:

“To make a sharp distinction between a religion which regards only country and a religion which regards only God and to speak only of obligations to God and to neglect obligations to ruler, to admonish only regarding the Way of universal humanity and to fail to teach the obligations which one has to his own countrymen, this cannot be called the teaching of the true God. But over against this, to teach only obligations to rulers and to omit to make clear one’s obligations to the Great Parent God of Heaven and Earth, to admonish regarding duties toward fellow countrymen and to consider not at all the Way of universal humanity, this is to fail to understand the full and perfect truth of sonship to the Great Parent God who is the reality of Heaven and Earth.”11

The founder was a lover of peace who taught in his own example the simple gospel of non-resistance. He prayed for those who raided his shrine and abused him. When, in the presence of misunderstanding and persecution, his followers lodged complaint with the local authorities he admonished them to leave the issue with God, saying, “When you receive injury because of the Way think not to escape by the strength of man. Though they smear your face with filth, God will wash it clean.”

The educational and social welfare activities of Konkō Kyō give practical reinforcement to its idealism. The most important of these include kindergartens in several places, a middle school for boys in the town of Konkō (the former Ōtani), a domestic science school for girls in Osaka, a coeducational training school for teachers and preachers, as well as various local and national activities provided for through young men’s associations, women’s societies, and organizations for boys and girls.

The fact that a movement so far removed from traditional myth and ritual should nevertheless be classified as Shintō is undoubtedly to be accounted for largely from the standpoint of convenience of registration with the national authorities. Formal connection with Shintō goes back to the year 1867. At this time Kawate in order to mitigate official opposition registered himself as a Shintō priest. Relationships and tendencies set up then have persisted ever since. Yet there is nothing in Konkō Kyō that is inconsistent with Shintō. It may be regarded as a fulfilment of Shintō.

1. See Holtom, D. C, “Konkō Kyō—A Modern Japanese Monotheism,” Journal of Religion, Vol. XIII, No. 3 (July, 1933), pp. 279–300.

2. He had various names in the course of his life. He was born into the family of Kadori Jūhei and was given the infant name of Genshichi. At the age of twelve he was adopted into the family of Kawate Kumejirō and took the name of Kawate Bunjirō. In later life when he had become famous as a religious teacher he named himself after the god whom he worshipped, calling himself and permitting others to call him, by the extraordinary title, “The Living God, the Great God, Konkō” (jkigami Konkō Daijin). By such means he attempted to give expression to a conviction of complete union with God— his mutuality with God, as he called it. His “roots,” he declared, were the same as those of God.

3. Bunka n. 8. 16.

4. Shinjin, “piety;” Bun, the reading of the first ideogram of his personal name.

5. Ansei 2. 4. 29.

6. Cf. Endō Ryōsuke, Konkō Kyō Yogi (“An Outline of Konkō Kyō”); Okayama Ken Konkō Machi, 1930; Harata, Genkō Konkō Kyōso to Sono Kyōgi (“The Founder of Konkō and His Teachings”); Okayama City, 1930.

7. See Konkō Kyō Kyōten (“The Sacred Texts of Konkō Kyō”); Okayama City, 1929, Konkō Iekuni, editor. Sakai, Eiji, Gorikai Shū wo Haidoku Shite (“A Commentary on the Gorikai), 4 Vols.; Okayama City, 1930.

8. Konkō, Iekuni, Konkōkyō no Kyōri (“The Doctrines of Konkō Kyō”), Uchū, Jan., 1930, p. 31.

9. A systematic account of the god-idea of Konkō Kyō is rendered difficult by the fact of development in apprehension of the nature of God on the part of the founder as well as by the fact of a total absence of orderly exposition of his fundamental ideas in the original texts. Hence a certain amount of variation and disagreement on the part of his modern interpreters. For example. one of the most recent of Konkō Kyō’s advocates, Mr. Hayata, denies that the god-idea is pantheistic, since in the founder’s belief God, although working through the physical universe and supporting it, nevertheless exists apart from it—nearer to dualism than pantheism. It is difficult to reconcile this with contemporary Konkō Kyō doctrine which declares that the created things of Heaven and Earth manifest the power and goodness of God. A similar misunderstanding arises out of the tolerant attitude of the founder toward the deified objects of faith of other religious systems. To construe this as an affirmation of polytheism misses the main point since Kawate, at least in his more mature thinking, certainly did not look on these miscellaneous deities as valid to his own personal worship.

10. Konkō Kyō Kyōten (“The Sacred Texts of Konkō Kyō”); Okayama City, 1929, pp. 70–71.

11. Hasegawa, Yūjirō, Konkōkyō Gaikan (“A Summary of Konkō Kyō”), pp. 126–7; Tōkyō, 1931.