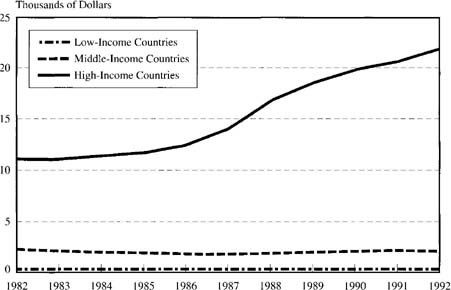

Figure 5-1 GNP per Capita, Atlas Method, for Low-, Medium-, and High- Income Countries, 1982–1992, in Current Dollars

SOURCE: World Bank, World Data ′94 CD-ROM (Washington: World Bank, 1994).

The management problems of the North-South system are quite different from those of the Western system. For the interdependent system of developed market economies, the crucial issue is whether it is possible to achieve the necessary political capability at the national, regional, and global levels to ensure that international economic relations continue to result in mutually beneficial outcomes while also modernizing (although not drastically altering) the international economic institutions that have been in place since World War II. The North-South system is separate from, but also embedded in, the Western system. It is separate because the rules of the North-South system reflect the much lower income levels and resource bases of the developing countries. It is embedded because the countries of the North (actually the West) have veto power over important changes in the system. The main question for the North-South system is whether it is possible to change the system so that more than a small number of developing countries benefit from it.

In the Western system, control is facilitated by a perceived common interest in the system. In the North-South system, there is less perception of a common interest. The developed market economies feel that the North-South system, although perhaps not perfect, is legitimate, because it benefits them and because they have significant decision-making authority. The Southern states tend to feel that both the Western and the North-South systems are illegitimate because they have not enjoyed a large enough share of the economic rewards. From their viewpoint, neither system has adequately promoted their economic development. Also, they feel that their interests are not properly represented in these international economic regimes.

One of the key sources of Southern grievances with the North-South system is the inability of the South to reduce the gap in average incomes between itself and the North. Average income, as measured by gross national product (GNP) divided by the total population (GNP per capita), was $21,960 in the 38 high-income countries, $2,440 in the 113 middle-income countries, and $390 in the 56 low-income countries in 1992. The total population of the three groups of countries in that year was 808 million, 1.4 billion, and 3.2 billion, respectively. The gap in average incomes appears to have increased between 1982 and 1992 (see Figure 5-1).l

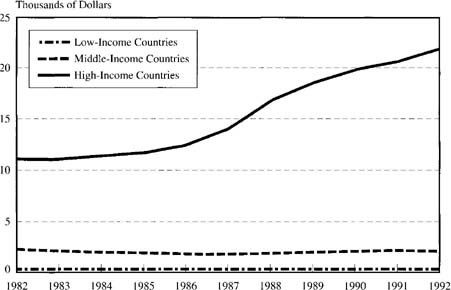

Global income is distributed quite unequally, and inequality may be increasing. The share of world income for the richest 20 percent of the global population rose from 70 percent to 85 percent from 1960 to 1991; the share of the poorest 20 percent declined from 2.3 percent to 1.4 percent during the same period.2 Average annual growth in nominal GDP between 1974 and 1992 was 5.5 percent in the low-income countries, 1.1 percent in the middle-income countries, and 2.6 percent in the high-income countries (see Figure 5-2).3 While economic growth rates were higher on the average in the South than in the North in recent years, high population growth rates and the relatively low income base of the South prevented economic growth from making much of an impact on the standard of living of the South's people, with the notable exception of a small number of very fast-growing countries. It is a hopeful sign, of course, that the two largest low-income countries—China and India—have experienced rapid growth in recent years.

Figure 5-1 GNP per Capita, Atlas Method, for Low-, Medium-, and High- Income Countries, 1982–1992, in Current Dollars

SOURCE: World Bank, World Data ′94 CD-ROM (Washington: World Bank, 1994).

Figure 5-2 Growth in Nominal GDP in Low-, Middle- and High-Income Countries, 1974–1992, in Percentages

SOURCE: World Bank, World Data ′94 CD-ROM (Washington: World Bank, 1994).

The management processes of the North-South system are quite different from those of the Western system. In the West, there is a relatively highly institutionalized system consisting of international organizations, elite networks, processes of negotiation, agreed-upon norms, and rules of the game. Although power is unequally distributed in the West, all members have access to both formal and informal management systems. In North-South relations, in contrast, there is no well-developed system with access for all. The South has been regularly excluded from the formal and informal processes of system management. North-South relations are controlled by the North as a subsidiary of the Western system. Understandably, the North perceives this structure as legitimate, whereas the South generally perceives it as illegitimate.

Since the end of World War II, developing countries have persistently sought to change their dependent role in international economic relations. As we shall discuss, their efforts to achieve growth and access to decision making have varied over time and from country to country. Southern strategies have been of three main types: (1) attempts to delink themselves from some aspects of the international economic system, (2) attempts to change the economic order itself, and (3) policies designed to maximize the benefits from integration into the prevailing system. These strategies have been shaped to a significant degree by the central question of whether it is possible to achieve growth and development within the prevailing international economic system. The dominant liberal philosophy argues that such development is not only possible but also most likely under a liberal economic regime. Two contending approaches—Marxist (and neo-Marxist) theories and structuralism—challenge the liberal analysis and argue that the system itself is at the root of the development problem.

Liberalism—especially as embodied in classical and neoclassical economics—is the dominant theory of the prevailing international economic system. Liberal theories of economic development argue that the existing international market structure provides the best framework for Southern economic development.4 The major problems of development, in this view, lie in the domestic economic policies of the developing country, which create or accentuate market imperfections, reduce productivity of land, labor, and capital, and intensify social and political rigidities. The best way to remedy these weaknesses is through the adoption of market-oriented domestic policies. Given appropriate internal policies, the international system—through increased levels of trade, foreign investment, and foreign aid flows—can provide a basis for more rapid growth and economic development.

Trade, according to liberal analyses, can act as an engine of growth. Specialization that is consistent with national comparative advantages increases income levels in all countries engaging in free or relatively open trade. Specialization in areas where the factors of production are relatively abundant promotes more efficient resource allocation and permits economic actors to apply more effectively their technological and managerial skills. It also encourages higher levels of capital formation through the domestic financial system and inflows of FDI. Private financial flows from developed countries can be used to fund investment in infrastructure and productive facilities. In addition, foreign aid from developed market economies, although not a market relationship, is believed to help fill resource gaps in less-developed countries by, for example, providing capital, technology, and education. Finally, specialization in the presence of appropriate antitrust enforcement can stimulate domestic competition and improve international competitiveness simultaneously.

From the liberal viewpoint, the correct international Southern strategy for economic development is to foster those domestic changes necessary to promote foreign trade, inflows of foreign investment, and the international competitiveness of domestic firms. In practice, this means the reversal of policies that hinder trade and investment flows, such as high tariffs and restrictions on FDI inflows, and the adoption of policies that increase domestic levels of competition—for example through the privatization of state enterprises, deregulation of overregulated markets, and other domestic reforms.

Marxist and neo-Marxist theories take a view that is opposite to that of the international market system.5 Southern countries, it is argued, are poor and exploited because of their history as subordinate elements in the world capitalist system. This condition will persist for as long as they remain part of that system. The international market is under the control of monopoly capitalists whose economic base is in the developed economies. The free flow of trade and investment, so much desired by liberals, enables the capitalist classes of both the developed and underdeveloped countries to extract the economic wealth of the underdeveloped countries for their own use. The result is the impoverishment of the masses of the Third World.

Trade between North and South is an unequal exchange, as control of the international market by the monopolies/oligopolies headquartered in the developed capitalist countries leads to declining prices for the raw materials produced by the South and rising prices for the industrial products produced by the North. Thus the terms of trade of the international market are biased against the South.6 In addition, international trade encourages the South to concentrate on backward forms of production that prevent development. The language of comparative advantage used by liberal free-traders masks their desire to maintain an international division of labor that is unfavorable to the South.

Foreign investment further hinders and distorts Southern development, often by controlling the most dynamic local industries and expropriating the economic surplus of these sectors through the repatriation of profits, royalty fees, and licenses. According to many Marxists, there is a net outflow of capital from the South to the North. In addition, foreign investment contributes to unemployment by establishing capital-intensive production, aggravating uneven income distribution, displacing local capital and local entrepreneurs, adding to the emphasis on production for export, and promoting undesirable consumption patterns.

Another dimension of capitalist creation and perpetuation of underdevelopment is the international financial system. Trade and investment remove capital from the South and necessitate Southern borrowing from Northern financial institutions, both public and private. But debt service and repayment further drain Third World wealth. Finally, foreign aid reinforces the Third World's distorted development, by promoting foreign investment and trade at the expense of true development and by extracting wealth through debt service. Reinforcing these external market structures of dependence, according to some Marxists and neo-Marxists, are clientele social classes within the underdeveloped countries. Local elites with a vested interest in the structure of dominance and a monopoly of domestic power cooperate with international capitalist elites to perpetuate the international capitalist system.

Because international market operations and the clientele elite perpetuate dependence, any development under the international capitalist system is uneven, distorted, and, at best, partial. For most Marxists and neo-Marxists, the only appropriate strategy for development is revolutionary: total destruction of the international capitalist system and its replacement with an international socialist system. They differ on whether it is possible to achieve this revolutionary ideal on a national basis or whether it is necessary for the revolution to be global, but they agree that revolutionary change is the only way to achieve true development in the South.7

Structural theory, which has had a significant influence on the international economic policy of the South, falls between liberalism and Marxism.8 Structuralist analysis, like Marxist analysis, contends that the international market structure perpetuates backwardness and dependency in the South and encourages dominance by the North. According to this view, the market tends to favor the already well endowed and to thwart the less developed. Unregulated international trade and capital movements will accentuate, not diminish, international inequalities, unless accompanied by reforms at the national and international levels.

The structural bias of the international market, according to this school, rests in large part on the inequalities of the international trading system. Trade does not serve as an engine of growth as asserted by the liberals but actually widens the North-South gap. The system creates declining terms of trade for the South. Income inelasticity of demand for the primary product exports of the less-developed countries (increased income in the North does not lead to increased demand for imports from the South) and the existence of a competitive international market for those products lead to lower prices for Third World exports. At the same time, the monopoly structure of Northern markets and the rising demand for manufactured goods lead to higher prices for the industrial products of the North. Thus, under normal market conditions, international trade actually transfers income from the South to the North.9

Structuralists also argue that international trade creates an undesirable dual economy. Specialization and concentration on export industries based on comparative advantages in agriculture or the extraction of raw materials by the Southern economies do not fuel the rest of the economy as projected by the liberals. Instead, trade creates an export sector that has little or no dynamic effect on the rest of the economy and that drains resources from the rest of the economy. Thus, trade creates a developed and isolated export sector alongside an underdeveloped economy in general.

Foreign investment, the second part of the structural bias, often avoids the South, where profits and security are lower than in the developed market economies. When investment does flow to the South, it tends to concentrate in export sectors, thereby aggravating the dual economy and the negative effects of trade. Finally, foreign investment leads to a net flow of profits and interest to the developed, capital-exporting North.

The structuralist prescription for promoting economic development in the South focuses on four types of policy changes: (1) import-substituting industrialization (ISI); (2) increased South-South trade and investment; (3) regional integration; and (4) population control. Structuralists assert that it is the specialization of Third World countries in the production and export of raw materials and agricultural commodities that hurts them in world trade because of the declining terms of trade for those products. Therefore the South needs to diversify away from agriculture and raw materials toward manufacturing and services activities. To do this, it may need to adopt high tariffs initially to encourage the establishment of domestic manufacturing facilities. This is the essence of import substitution.

Second, the South needs to reduce trade barriers among the developing countries in order to compensate for the generally small size of their domestic markets and to achieve economies of scale similar to those enjoyed by the industrialized nations of Europe, Asia, and North America. The best way to do this is to foster regional integration agreements among the developing countries, not unlike the ones that helped to bring prosperity to Western Europe after World War II. Increased South-South trade would be advantageous not just in adding to total world demand for exports from the South but also in allowing developing countries to develop technologies appropriate for the South, to counter the power of Northern MNCs, and to increase generally the competitiveness of businesses headquartered in the South.

Finally, structuralists like Raul Prebisch and W. Arthur Lewis recognized that a key problem that had to be addressed was the depressing effect of rapid population growth on the average wages of Third World workers. If population growth could be reduced by appropriate population control policies, then it would be easier to achieve high standards of living for the impoverished masses of the South. Politically, this was the least popular part of the structuralist policy agenda, but it has received greater attention in recent years.

Although the structuralist analysis of the international market is similar to the Marxist analysis in its stress on the negative effects of the declining terms of trade of the developing countries, the two theories diverge on a critical point. Structuralist theory argues that the international system can be reformed, that the natural processes can be altered. Although the various theorists differ on preferred reforms—foreign aid, protection, access to Northern markets—they all believe that industrialization can be achieved within a reformed international market and that such industrialization will narrow the development gap.

Marxist theories, on the other hand, contend that the capitalist system is immutable, that it will defend itself, and that the only way to change it fundamentally is through revolution: destruction of the international capitalist system and its replacement with an international socialist system. Marxists explain the impossibility of reform in two ways.

One explanation is that developed capitalist economies are unable to absorb the economic surplus or profits generated by the capitalist system of production.10 Capitalist states cannot absorb their rising surplus internally through consumption, because the worker's income does not grow as fast as capitalist profits do. To prevent unemployment and the inevitable crisis of capitalism resulting from overproduction and underconsumption, the developed market economies invest excess capital in and export excess production to the underdeveloped countries. Another way to absorb the rising surplus and prevent the crisis of capitalism, according to some, is to invest in the military at home, which in turn leads to pressure for expansion abroad. By absorbing economic surplus, foreign expansion prevents or at least delays the collapse of the capitalist system. Thus, dominance, dependence, and imperialism are essential and inevitable dimensions of capitalism.

A second explanation of the necessity of capitalist imperialism derives from the North's need for Southern raw materials.11 According to this argument, capitalist economies depend on Southern imports, and the desire to control access to those supplies leads to Northern dominance.

Empirical examination reveals important weaknesses in all three perspectives. We will start with the Marxist approach. Although some economic ties with the South are important to the developed countries, they are for the most part not crucial to the North's economic well-being. Indeed, as we shall discuss, the problem for the less-developed countries may be that they are not important enough for the North.

First, the underconsumption arguments of the Marxists are weak, because the developed market economies are able to absorb their economic surplus. While the developed economies have had difficulties maintaining aggregate demand at acceptable levels, they have managed the problem internally through modern economic policies: income redistribution, fiscal and monetary policy, and public and social expenditures—what has come to be called the “welfare state.” Although the developed countries have had serious economic problems—sluggish growth, surplus industrial capacity, inflation—these cannot be adequately explained by underconsumption theories.

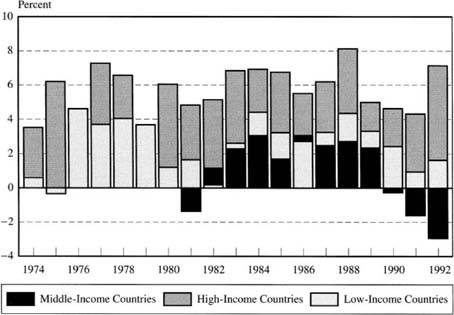

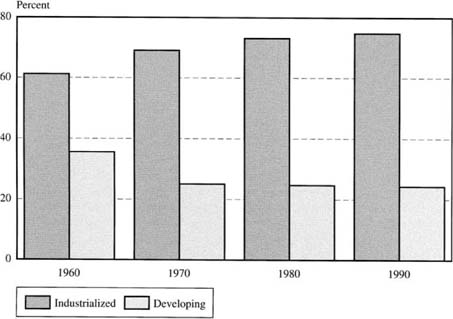

Second, foreign investment, especially in less-developed markets, is not of vital importance to the developed market economies, as illustrated by the case of the United States, the principal foreign investor. Foreign investment is a relatively small percentage of total U.S. investment. In 1992, U.S. outward FDI was $34.8 billion, or 3.8 percent of total investment in fixed capital for that year (see Figure 5-3). In 1992, U.S. stock in overseas FDI amounted to $474 billion, whereas its total investment was in the trillions of dollars. Furthermore, the South is not the main area of U.S. foreign investment and is, in fact, declining in importance. In 1991, the developing countries accounted for 25 percent of all U.S.

Figure 5-3 U.S. FDI Outflows Compared with Domestic Fixed Capital Investments, 1965–1992, in Current Dollars

SOURCE: World Bank, World Data '94 CD-ROM (Washington: World Bank, 1994).

direct foreign investment, whereas the developed market economies accounted for 74 percent. In 1960, U.S. direct foreign investment in the South accounted for 35 percent, versus an investment of 61 percent in the developed market economies (see Figure 5-4).12

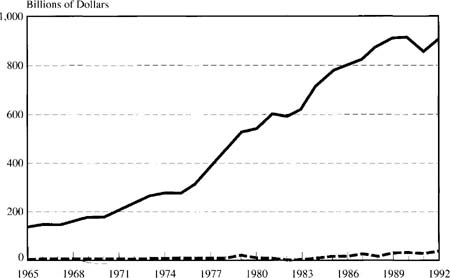

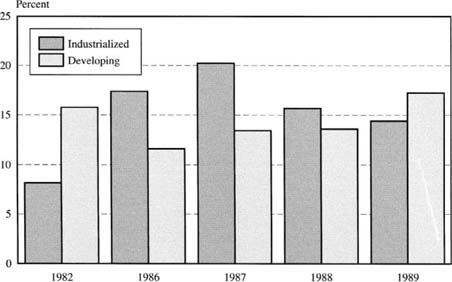

Moreover, income from the developing countries is not of vital economic importance to the United States. In 1991, Southern earnings accounted for 40 percent of total U.S. earnings on foreign direct investment, about 9.3 percent of total business earnings, and an infinitesimal part of its total GNP.13 Although Southern investment is a small part of total foreign investment, returns for many years were greater in the less-developed countries. In 1982, the rate of return on U.S. investments in the Third World was 15.8 percent, as compared with an 8.2 percent return in the North.14 This situation was reversed in 1986–1988. For example, in 1986, the rate of return on investments in industrialized countries was 17.5 percent, while it was 11.8 percent in the developing countries. The rate of return on investments in developing countries once again exceeded that on investments in industrialized countries in 1989 (see Figure 5-5).15 In sum, U.S. investment in and earnings from the developing countries are significant but hardly crucial to the overall U.S. economy.

Trade with the South as a whole is also not of overwhelming economic importance to the North. In 1993, exports from developed to developing countries accounted for 28.8 percent of exports of the developed market economies, of

SOURCE: Statistical Abstract of the United States (Washington: Government Printing Office, various years).

which 12.9 percent was exports to oil-exporting LDCs. In the same year, imports of the developed countries from the LDCs were 28.1 percent of total imports of which 17.9 percent was from oil exporters.16 The minor overall importance to the United States of trade with the South is demonstrated by the fact that in 1992, U.S. exports to developing countries represented only 3.1 percent of the U.S. GNP.17

In sum, the case for dependence as a necessary outlet for capitalist surplus is not sustainable. The underdeveloped countries provide significant earnings for the developed market economies and are important investment and export outlets, but they are not crucial for the survival of the North. The available data suggest that the economic importance of the South for the North has declined overall in the decades since World War II, with the notable exception of dependence of the North on petroleum exports from the South (see Chapter 9).

But Northern dependence on Southern raw materials is also limited. Raw materials in general are not as significant as Marxist theory suggests, and, where they are significant as with oil, raw material dependence may work to the detriment of the developing countries, not to their advantage. The United States, and to a greater extent the Europeans and Japanese, depend on the import of certain

Figure 5-5 Rate of Return on U.S. Foreign Investments in Industrialized and Developing Countries, 1982–1989, in Percentages

SOURCE: Survey of Current Business (Washington: Department of Commerce, August, 1990), 60.

raw materials, but in only a few cases are the major suppliers of these materials Southern countries.18 Furthermore, foreign dependence is declining as growth in overall consumption of raw materials declines due to changing growth patterns, conservation, technological improvements, and substitution.

In conclusion, the arguments that dominance and exploitation of the South are necessary for the capitalist economies as a whole do not stand the empirical test. The South is important but not vital.

There is, however, the Marxist argument that dependence, although not important to the capitalist economies as a whole, is necessary for the capitalist class that dominates the economy and polity.19 According to these theories, capitalist groups, especially those managing the multinational corporations, seek to dominate the underdeveloped countries in their quest for profit. Because these groups control the governments of the developed states, they are able to use governmental tools for their class ends.

To evaluate this theory, it is necessary to determine whether the capitalist class as a whole has a common interest in the underdeveloped countries, even though most capitalists do not profit, as has been shown, from foreign trade and investment. Arthur MacEwan argues that the entire capitalist class has an interest in dominance and foreign expansion, including those capitalists having no relation to or profit from such expansion.20 This is true, he explains, because there is a common interest in expansion that maintains the system as a whole. Yet the preceding analysis of the macroeconomic importance of the Third World suggests that the less-developed countries are not economically necessary to the North and that certain Northern groups, such as the petroleum industry, enjoy most of the benefits of economic ties with the South. Thus, the capitalist class as a whole does not have an interest in the South and in dominance, because only a small percentage of that class profits from dominance and because the system itself is not dependent on dominance.

A stronger argument is that some powerful capitalists, such as the managers of multinational corporations, have a crucial interest in the South and in Northern dominance. Clearly, certain firms and certain groups profit from the existing structure of the international market. The question is the role of these firms and these groups in Northern governmental policy. Certainly, those groups interested in Northern economic dominance can affect the foreign policies of developed countries.21 But they do not inevitably dominate foreign policy in the developed market economies. In the Middle East, for example, despite the importance of oil earnings and petroleum, U.S. foreign policy has not always reflected the interests of the U.S. oil companies.22

On balance, then, dominance is important to the developed market economies and is especially important to certain groups within those economies. But dominance is neither necessary nor inevitable. Under the right political circumstances, change is possible. The problem is that the South has only limited ability to demand change from the North. Economically underdeveloped and politically fragmented, the South has limited leverage on the North. As we shall discuss, because the South is not vital for the North, the developed countries need not respond to Southern demands for change.

The Marxist perspective is not alone in having some difficulties in reconciling theory with evidence. The liberal perspective has trouble explaining a number of empirical anomalies as well. For example, neoclassical trade theory, as embodied in the Hecksher-Ohlin (H-O) theory of international trade, explains trade in terms of differences in comparative advantages across countries. Comparative advantages are determined by the relative abundance or lack of key factors of production (e.g., labor, land, and capital). But, “nearly half of the world's trade consists of trade between industrialized countries that are similar in their factor endowments.”23 If H-O theory were correct, then most of the world's trade would be North-South trade instead of North-North trade.

One way that neoclassical theories have tried to deal with this anomaly is by examining the effects of trade barriers on North-South trade.24 Another is to relax the assumptions of H-O theory concerning declining returns to scale and the existence of competitive markets.25 Yet another is to provide separate explanations of inter- and intra-industry trade.26 Each approach has its merits, but there is still no overarching theory of trade that satisfactorily explains recent patterns in world trade.

In addition, liberals have problems explaining why countries with strongly interventionist governments, like Japan and South Korea, have done so well at promoting exports. According to the liberal orthodoxy, countries with governments that maintain a hands-off approach to promoting international competitiveness are more likely to end up with internationally competitive firms than those with interventionist governments.

Finally, despite the arguments of liberals for several decades that there should not be a long-term trend toward declining terms of trade for the developing countries, the evidence appears rather to support the contentions of both Marxists and structuralists that such a downward trend exists.

The main criticism of the structuralists, besides the one just mentioned concerning the lack of solid evidence for declining terms of trade, have to do with the relative ineffectiveness and undesirability of import substitution as a development strategy. We deal with this criticism in the next section.

Since the end of World War II, developing countries have pursued several different strategies in an effort to alter their dependence. In finance, trade, investment, and commodities, they have sought greater rewards from the greater participation in the international economic system. Over the years, those strategies have alternated between seeking to change the system and seeking to accommodate to it.

During the formative period of Bretton Woods, those developing states that were independent—primarily the Latin American countries—attempted to incorporate their goal of economic development and their view of appropriate international strategies for development into the North's plans for the new world economic order. The political and economic weakness of the developing world at this time doomed their efforts. At Bretton Woods, they sought, and failed, to ensure that development—meaning development for both industrial and developing countries—would have the same priority as reconstruction did in the activities of the new International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. At Havana, they argued for modification of the free-trade regime: for the right to protect their infant industries through trade restrictions such as import quotas and for permission to stabilize and ensure minimum commodity prices through commodity agreements. Some LDC interests, such as the right to form commodity agreements and to establish regional preference systems to promote development, were, in fact, included in the Havana Charter. But these provisions were lost when the charter was not ratified and the GATT took its place.27

In the 1950s and 1960s, developing countries abandoned these first efforts to shape the international system and turned inward. Faced with an international regime that they believed did not take their interests into account and that excluded them from management, developing countries turned to policies of diversification and industrialization via import substitution. The stress on industrialization was reinforced by the preoccupation of developing countries with decolonization and by the belief that the end of colonial political exploitation would foster economic development.

In this period, the main development strategy was import substitution. Developing countries protected local industry through tariffs, quantitative controls, and multiple exchange rates, and they favored production for local consumption over production for export. Governments became actively involved in promoting economic development, largely by channeling resources to the manufacturing sector. Import substitution did not mean total isolation from the international system. Trade with the North continued to flow. Developing countries also encouraged inflows of foreign direct investment, especially in manufacturing, as a way of fostering domestic productive capacity. As a result, there was a major movement of multinational corporations into developing countries. LDCs also tried with some success to persuade developed countries to provide foreign aid for development. As decolonization swept the Third World and competition with the Soviet Union shifted to the South, aid became a useful political tool in the Cold War as well as a way for colonial powers to retain links with their former colonies. During this time, aid became a regular feature of North-South relations.

Toward the end of this period, elements of a new strategy began to emerge. Import substitution gradually came to be seen as a failure. High tariff barriers that were supposed to be temporary became more or less permanent, thanks to the successful lobbying of domestic interests that wanted the barriers kept high. Import substitution therefore created uncompetitive industries while at the same time weakening traditional exports. The foreign investment that jumped over the high tariff barriers of the Third World came to be seen as a threat to sovereignty and development. Foreign aid and regional integration proved inadequate to ensure economic growth. Instead of relying on domestic change, developing countries began to argue that only changes in the international system could promote development. As independent developing countries became more numerous, they began to meet with each other and to develop plans for changing the prevailing international economic regime. The hope was that such common action would increase the bargaining leverage of the South and enable the less-developed countries to negotiate that change with the North.

In the 1960s, developing countries gradually began to work together to press for changes in the system. They created the Group of Seventy-Seven (G-77) to act as a permanent political bloc to represent developing country interests in U.N. forums. In Third World conferences and United Nations forums where the South commanded a majority, the G-77 pushed through declarations, recommendations, and resolutions calling for economic reforms.28

The developing countries achieved some largely procedural changes. They persuaded the GATT to include economic development as one of its goals. The United Nations established the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), which the South intended to be its international economic forum. UNCTAD provided the developing countries with a new economic doctrine that followed the ideas of the structuralists. As UNCTAD's first secretary general, Raúl Prebisch argued that what was needed was a redistribution of world resources to help the South: restructuring of trade, control of multinational corporations, and greater aid flows.

The strategy of seeking to change the international system reached its apex in the 1970s with the South's call for a New International Economic Order (NIEO).29 The NIEO grew out of the threat and the promise of the economic crises of the 1970s. The combination of food shortages, the rapid increase in the price of oil, and a recession in the developed countries undermined growth prospects in much of the South and made developing countries desperate for change. At the same time, the success of the oil-producing and oil-exporting countries in forcing changes in the political economy of oil held out the prospect of new leverage on the developed countries. Developing countries sought to use their own commodity power and to link their interests with OPEC, their fellow members of the G-77, to demand changes in the global economic system. The NIEO included a greater Northern commitment to the transfer of aid and new forms of aid flows; greater control of multinational corporations and greater MNC transfer of technology to developing countries; and trade reforms including reduction of developed country tariff barriers and international commodity agreements.

Success of the NIEO depended on Southern unity, the credibility of the commodity threat, and the North's perception of vulnerability. It foundered on all three. Southern unity was weakened by the differential impact of the food, energy, and recession crises; by the growing gap between the NICs and the least-developed countries; and by traditional regional and political conflicts. The credibility of the commodity threat was undermined by the inability to develop other OPECs, by OPEC's unwillingness to link the oil threat to G-77 demands in any meaningful way, and by declining demand for Southern raw materials. And, in the end, the North did not perceive any significant vulnerability to Southern threats. The North was willing to enter into a dialogue about changing the international economic system—as in the 1975 to 1977 Conference on International Economic Cooperation (CIEC)—but it was unwilling to make any substantive changes.

By the 1980s, developing countries had effectively abandoned the hope of reforming the international system and were once again thrown back on their own resources. The recessions and debt restructurings of the 1980s made the industrialized countries even less responsive to demands for systemic change and less willing to dispense foreign aid. The failure of the NIEO led developing nations to pursue different routes to development.

The G-77 survived as a bargaining group in the United Nations, but Southern unity became increasingly irrelevant to the development strategy of most Southern states. The developing countries were increasingly fragmented. A number of countries in Asia achieved rapid growth largely by integrating into the system, welcoming foreign investment, and exporting manufactured products to developed countries. Other advanced developing countries, such as Brazil and Mexico, relied on a relatively closed internal market.30 The interests of these countries increasingly departed from those poorer countries, especially in Africa, which existed at the poverty line and relied on foreign assistance for survival. Even the NICs were divided. Those in Asia became concerned about growing protectionism in the United States; others, especially Latin American countries that had borrowed heavily from commercial banks, faced the debt crisis; others such as Mexico and Venezuela faced the collapse of oil prices and the growing conflicts within OPEC.

The debt crisis of the 1980s played an important role in the rethinking of development strategies that occurred during the decade. The need to generate new sources of exports to service the debts accumulated in the 1970s created enormous incentives to adopt export-oriented development strategies and to jettison, or at least modify significantly, the import substitution policies of the past. Indebted countries that were unable to increase exports had to adopt governmental austerity measures that generally hurt the poorest part of the population the most. The success of the Asian NICs and the failure of protectionist and statist policies led to a rethinking of effective strategies for development and to the adoption of liberal domestic and international economic policies. Some faster-growing countries in the South also began to experience problems of environmental degradation. In the 1980s, people of the South began to flow North in unprecedented numbers in search of greater political freedoms and economic opportunities. Some entered the North legally, others illegally. Debt, environmental concerns, and migration issues dominated the North-South agenda by the end of the 1980s as a result.

The issue for developing countries, as the end of the twentieth century has approached, has remained little different than it was in 1945: whether it was possible to achieve growth and development within the prevailing system and, if so, how. While the North was not prepared to make major changes in the system to help the South, it was willing to transfer funds and to offer advice and encouragement for adopting export-led growth development strategies. Furthermore, the North was increasingly interested in Southern markets and concerned about preventing further degradation of the global environment and reducing the flow of Southern peoples to the North. This concern was clearly evidenced in the U.S. debate over NAFTA. It remained to be seen whether these new Northern preoccupations were enough to overcome the deep divisions between the two groups of countries.

1. The World Bank defined low-income countries as those countries with per capita income less than $675; middle-income as those with per capita income in the $675 to $8,355 range; and high-income as those with per capita income higher than $8,355. See World Bank, World Tables 1994 (Washington: World Bank, 1994) 748, for the list of countries in each category.

2. United Nations Development Program, Human Development Report 1994 (New York: Oxford University Press for the UNDP, 1994), 35.

3. World Bank, World Data '94 CD-ROM (Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 1994).

4. For examples of liberal theory, see Gottfried Haberler, International Trade and Economic Development (Cairo: National Bank of Egypt, 1959); Ragnar Nurkse, Equilibrium and Growth in the World Economy (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1961); Walt W. Rostow, The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1962); Walt W. Rostow, Politics and the Stages of Growth (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1972); Gerald M. Meier, International Trade and Development (New York: Harper and Row, 1963); Gerald M. Meier, ed., Pioneers in Development (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984); Harry G. Johnson, Economic Policies Toward Less Developed Countries (New York: Praeger, 1967); and Jagdish Bhagwati, Essays in Development Economics: Wealth and Poverty, vol. 1, and Dependence and Interdependence, vol. 2 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1985). For an interesting overview of the literature, see Walt W. Rostow, Theorists of Economic Growth from David Hume to the Present (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

5. For examples of Marxist and neo-Marxist perspectives, see Samir Amin, Accumulation on a World Scale (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1974); Samir Amin, Unequal Development: An Essay on the Social Formations of Peripheral Capitalism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1976); Paul A. Baran, The Political Economy of Growth (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1968); Fernando H. Cardoso and Enzo Faletto, Dependency and Development in Latin America, trans. Marjory Mattingly Urquidi (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979); Arghiri Emmanuel, Unequal Exchange: A Study of the Imperialism of Trade (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1972); Andre Gunder Frank, Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America, rev. ed. (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1969); Harry Magdoff, Imperialism: From the Colonial Age to the Present (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1978); Dan W. Nabudere, The Political Economy of Imperialism (London: Zed Press, 1977); Theotonio Dos Santos, “The Structure of Dependence,” in K. T. Fann and Donald C. Hodges, eds., Readings in U.S. Imperialism (Boston: Porter Sargent, 1971); and Immanuel Wallerstein, The Capitalist World Economy (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1979). See also “Facing the 1980s: New Directions in the Theory of Imperialism,” a special issue of the Review of Radical Political Economics, 11 (winter 1979).

6. This is a view shared by non-Marxist theorists as well. See the section below on structuralist approaches.

7. This brief summary does considerable violence to the richness and diversity of views within the Marxist and neo-Marxist schools. For more nuanced summaries, see Fernando H. Cardoso, “The Consumption of Dependency Theory in the United States,” Latin American Research Review 7 (fall 1977): 7–24; Raymond Duvall, “Dependence and Dependencia Theory,” International Organization 32 (winter 1978): 51–78; Ronald Chilcote, “Dependence: A Critical Synthesis of the Literature,” Latin American Perspectives 1 (spring 1974): 4–29; and Gabriel Palma, “Dependency: A Formal Theory of Underdevelopment or a Methodology for the Analysis of Concrete Situations of Underdevelopment,” World Development 6 (1978): 881–924.

8. For examples of structuralist theory, see Gunnar Myrdal, Rich Lands and Poor: The Road to World Prosperity (New York: Harper and Row, 1957); Raúl Prebisch, “Commercial Policy in the Underdeveloped Countries,” American Economic Review 49 (May 1959): 251–273; Raúl Prebisch, The Economic Development of Latin America and Its Principal Problems (New York: United Nations, 1950); W. Arthur Lewis, The Evolution of the International Economic Order (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978); and Johan Galtung, “A Structural Theory of Imperialism,” Journal of Peace Research 8(1971): 81–117.

9. This is the essence of the argument put forward by Raúl Prebisch, one of the most influential advocates of the structuralist perspective. See Joseph L. Love, “Raúl Prebisch and the Origins of the Doctrine of Unequal Exchange,” Latin American Research Review 15 (1980): 45–72.

10. Paul A. Baran and Paul M. Sweezy, Monopoly Capital: An Essay on the American Economic and Social Order (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1966). These authors define economic surplus as “the difference between what a society produces and the costs of producing it” (p. 9). For a critical analysis of the concept, see Benjamin J. Cohen, The Question of Imperialism: The Political Economy of Dominance and Dependence (New York: Basic Books, 1973): 104–121.

11. See, for example, Pierre Jalée, Imperialism in the Seventies, trans. R. and M. Sokolov (New York: Third World Press, 1972).

12. U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States 1974 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1974), 781; and Statistical Abstract of the United States 1993 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office), 801.

13. U.S. Department of Commerce, Survey of Current Business (August 1990), 60.

14. U.S. Department of Commerce, Survey of Current Business (August 1988): 45; (July 1988): 86.

15. U.S. Department of Commerce, Survey of Current Business (August 1988): 45.

16. International Monetary Fund, Direction of Trade Statistics, Yearbook 1994 (Washington: IMF, 1994), 10, 16.

17. International Monetary Fund, Direction of Trade Statistics Yearbook, 1994 (Washington: IMF, 1994), 420.

18. Commodity Research Bureau, 1986 CRB Commodity Yearbook (Jersey City, N.J.: CRB, 1986).

19. See Arthur MacEwan, “Capitalist Expansion, Ideology and Intervention,” Review of Radical Political Economics 4 (spring 1972), 36–58; and Thomas Weisskopf, “Theories of American Imperialism: A Critical Evaluation,” Review of Radical Political Economics 6 (fall 1974), 41–60.

20. MacEwan, “Capitalist Expansion.”

21. See U.S. Senate, Multinational Corporations and United States Foreign Policy, hearings before the Subcommittee on Multinational Corporations of the Committee on Foreign Relations, 93rd Cong., 2nd sess. (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1975).

22. On this question, see Stephen Krasner, Defending the National Interest (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978); G. John Ikenberry, Reasons of State: Oil Politics and the Capacities of American Government (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1988); and Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991).

23. Elhanan Helpman and Paul Krugman, Increasing Returns, Imperfect Markets, and International Trade (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1985), 2.

24. See, for example, James R. Markusen and Randall M. Wigle, “Explaining the Volume of North-South Trade,” Economic Journal 100 (December 1990): 1206–1215.

25. This is the approach suggested by the work of Helpman and Krugman and other strategic trade theorists.

26. See Edward E. Learner, Sources of International Comparative Advantage: Theory and Evidence (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1984).

27. See Richard Gardner, Sterling Dollar Diplomacy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1956); Robert Hudec, The GATT Legal System and World Trade Diplomacy (New York: Praeger, 1975); and Janette Mark and Ann Weston, “The Havana Charter Experience: Lessons for Developing Countries,” in John Whalley, ed., Developing Countries and the Global Trading System, Vol. 1, Thematic Studies for a Ford Foundation Project (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989).

28. Branislav Gosovic and John G. Ruggie, “On the Creation of the New International Economic Order,” International Organization 30 (spring 1976): 309–346; Robert A. Mortimer, The Third World Coalition in International Politics, 2nd ed. (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1984), ch. 3; and Marc Williams, Third World Cooperation: The Group of 77 in UNCTAD (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1991), 78.

29. Robert Rothstein, Global Bargaining: UNCTAD and the Quest for a New International Economic Order (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979); Jeffrey Hart, The New International Economic Order: Conflict and Co-operation in North-South Economic Relations 1974–77 (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1983); Craig Murphy, The Emergence of the NIEO Ideology (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1984); and Stephen D. Krasner, Structural Conflict: The Third World Against Global Liberalism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985).

30. Stephan Haggard, Pathways from the Periphery (Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1990); Alice H. Amsden, Asia's Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization (New York: Oxford, 1989); and Robert Wade, Governing the Market: Economic Theory and the Role of Government in East Asian Industrialization (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990).