We have now considered the general morphology of the Eskimo or, more specifically, the constant features of this morphology. But we know that this morphology also varies according to the time of year; we must now examine these variations, as these are the main concern of this study. Although the settlement is always the fundamental unit of Eskimo society, it still takes on quite different forms according to the seasons. In summer, the members of a settlement live in tents and these tents are dispersed; in winter, they live in houses grouped close to one another. Everyone, from the earliest authors onward,1 who has had a chance to follow the cycle of Eskimo life, has observed this general pattern. First, we are going to describe each of these two types of habitat and the two corresponding ways of grouping. We shall then endeavour to determine their causes and their effects.

The tent

We begin by considering the tent,2 because it is a simpler construction than the winter house.

Everywhere, from Angmagssalik to Kodiak Island, the tent has the same name, lupik,3 and the same form. In structure it consists of poles arranged in the shape of a cone;4 over these poles are placed skins, mostly of reindeer, either as separate pieces or stitched together. These skins are held down at the base by large stones capable of withstanding the often severe force of the wind. Unlike Indian tents, Eskimo ones are not open at the top; there is no smoke that has to be allowed to escape, for their lamps produce none. The entrance can be closed tightly, and then the occupants are plunged in darkness.5

The normal type of tent naturally varies somewhat according to locality; but these variations are completely secondary. Where reindeer are rare,6 as at Angmagssalik and throughout eastern Greenland, the tent is made of sealskin; since wood is scarce, the form of the tent is also somewhat different. It is placed in a spot with a steep slope7 so that it leans against the earth; a horizontal beam supported in front by an angular frame is sunk in the ground and skins and thin laths are laid on this. The same conditions, remarkably enough, produce the same effects both among the Iglulik8 on Hudson Bay and in the southern part of Baffin Land.9 Since narwhal bones often replace wood, the tent has a form that is strikingly similar to that at Angmagssalik.

Rather than all these technological details, it is more important to know what kind of group lives in the tent. From one end of the Eskimo area to the other, this group consists of a family10 defined in the narrowest sense of this word: a man and his wife (or, if there is room, his wives) plus their unmarried children including adopted children. In exceptional cases, a tent may include an older relative, or a widow who has not remarried and her children, or a guest or two. The relationship between the family and the tent is so close that the structure of the one is modelled on the structure of the other. It is a general rule, among all Eskimo, that there should be one lamp for each family; thus, ordinarily, there is only one single lamp to a tent.11 Similarly, there is only one bench (or raised bed of leaves and branches at the back of the tent) covered with skins for sleeping; this bed has no partition to separate the family from any guests.12 Thus the family lives perfectly united within this tightly closed interior; it builds and transports this summer dwelling which is made exactly to its measure.

The house

As summer turns to winter, there occurs a complete change in the morphology of Eskimo society, in its mode of livelihood and in the structure of its sheltered groups. Eskimo dwellings do not remain the same; their population is different, and they are arranged in a completely different settlement pattern.

Instead of tents, Eskimo build houses,13 and indeed long-houses,14 as winter dwellings. We will begin by describing the external form of these houses and then proceed to discuss their content.

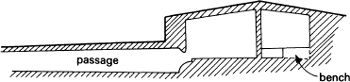

The Eskimo long-house is made up of three essential elements which serve to identify it: (1) a passage that begins outside and leads into the interior via a partially subterranean entrance; (2) a bench with places for lamps; and (3) partitions which divide the bench into a certain number of sections. These distinctive traits are specific to the Eskimo house; they are not found together in any other known type of house.15 In different localities, however, houses may have particular characteristics which give rise to a certain number of secondary varieties.

Figure 1 Cross-section of the house at Angmagssalik (Henri Beuchat).

Figure 2 Floor plan of the house at Angmagssalik (Henri Beuchat).

At Angmagssalik,16 houses are 24 to 50 feet long and 12 to 16 feet wide. They are constructed on land that generally has a steep slope (see Figures 1 and 2). The earth is excavated in such a way that the rear wall is at almost the same level as the surrounding land. This rear wall is somewhat larger than the wall that forms the front of the house. This arrangement gives the misleading impression that the house is below ground. The walls are of stone, or of wood covered with turf and often with skins; inner walls are almost always covered. In front and always at a right-angle with the wall is the passage whose entrance is so low that one can enter the house only on one’s knees. Inside, the earth is covered with flat stones. At the rear of the house is a low continuous bench, from 4 to 5 feet wide and raised about 1 feet from the ground. In Angmagssalik, it is actually supported by stones and turf, but elsewhere, in southern and western Greenland,17 it rests on stakes; this is also the case in the Mackenzie region18 and in Alaska.19 This bench is divided into compartments by a short partition: each of these compartments, as we shall see, corresponds to a family and in the front of each of the compartments is placed the family lamp.20 Along the front wall is another smaller bench which is reserved for adolescent unmarried young people or guests when they are not invited to share the family bed.21 In front of the house are storage places for provisions such as frozen meat, props for boats and, sometimes, a kennel for the dogs.

feet from the ground. In Angmagssalik, it is actually supported by stones and turf, but elsewhere, in southern and western Greenland,17 it rests on stakes; this is also the case in the Mackenzie region18 and in Alaska.19 This bench is divided into compartments by a short partition: each of these compartments, as we shall see, corresponds to a family and in the front of each of the compartments is placed the family lamp.20 Along the front wall is another smaller bench which is reserved for adolescent unmarried young people or guests when they are not invited to share the family bed.21 In front of the house are storage places for provisions such as frozen meat, props for boats and, sometimes, a kennel for the dogs.

In the Mackenzie region22 where driftwood is abundant, houses are built entirely of logs: large pieces of wood resting on one another and set in a square with space on each side. When seen from above, the plan is more that of a star-shaped polygon than that of a rectangle, as is the case with the previous kind of house. A further difference is that it is composed of four distinct compartments. Each compartment has a bench that is slightly higher than the benches in houses in Greenland. In the compartment with the entrance, the bench is divided in two by the entry-way and, like the bench for guests in Greenland, these benches are reserved for guests and for utensils.23 A final difference is that the passage into the house is even lower than that in Greenland and leads into the compartment which faces the sea, preferably towards the south24 (see Figure 3).

In Alaska we find a house that is an intermediate type between the two preceding ones. The plan once more becomes rectangular,25 as in Greenland, but it often consists of several rectangles grafted onto a single passage.26 Since wood is also abundant throughout southern Alaska, the floor of the central rectangle is covered with planks. The only characteristic that appears to be specific to houses in this region is the arrangement of the passage; instead of leading into the house through one of the walls, it proceeds underground and ends up in the central portion of the house.27

Figure 3 Floor plan and cross-section of the Eskimo house in the Mackenzie region. Both have been redrawn to our specifications because the drawings in Petitot (1876) are plainly inaccurate, while those in Franklin (1828) are incomplete.

It is easy to see how these different kinds of houses are merely variations on the same fundamental type, for which the Mackenzie house provides perhaps the closest approximation. The various materials that the Eskimo have at their disposal in the different regions are an important factor that contributes to determining these variations. Thus, at certain points in the Bering Strait,28 in Baffin Land29 and in the north-west region of Hudson Bay,30 driftwood is rare or totally absent.31 Here whale-ribs are used instead, but this results in a different kind of dwelling. The house is small, not very high, and is round or oval. The walls are covered with skins which are overlaid with turf; over the walls there is a kind of dome. This is called the qarmang, and it has its own passage.

Let us suppose now that this last resource of the Eskimo builder, whale-ribs, were unavailable; then, other forms appear. The Eskimo often has recourse to a primary material that he knows is marvellously useful and is always at hand: namely, snow.32 Thus the igloo or snow-house is found in Baffin Land33 and along the northern coast of America.34 The igloo has all the essential features of a large house: it is usually a multiple or composite house;35 two or three igloos are linked and open onto the same passage; it is always dug into the earth and is always equipped with a passage whose entry is partially underground; and, finally, it contains at least two benches of snow with two places for lamps36 (see Figure 4). We can also establish historically that the igloo is a substitute for the rectangular or polygonal house. In 1582, writing about the Meta Incognita Peninsula, Frobisher describes huts made of earth and turf.37 A little later, Coats finds the same kind of hut further away.38 At this time, however, both climate and currents were different from those that gradually developed between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries.39 It is therefore quite possible that driftwood was already rare in the sixteenth century, so rare, in fact, that its use was reserved for tools and weapons. Hence more and more qarmang were built. In 1829 Parry finds entire villages of houses made from whalebones.40 But these villages themselves gradually became impossible as European whalers devastated the straits and bays of the Arctic archipelago.41

Figure 4 Floor plan and cross-section of a simple igloo from the north-west region of Hudson Bay (Henri Beuchat).

igdluling: passage and recess for dogs.

uadling: cooking area and sump. The small side vaults are used for storing provisions.

Where there is neither wood nor whalebones, the only resort is to stone. One tribe on Smith Strait attempted this.42 At the time of the arrival of the first Europeans, this tribe was in a miserable state.43 The expansion of inland ice and the persistence of drifting ice throughout most of the year not only put an end to the arrival of driftwood but obstructed large whales, and made it impossible to hunt whales, walruses and seals in open waters.44 The bow, the kayak, the umiak and most of the sleds disappeared because of a lack of wood. These unfortunate Eskimo were reduced to such circumstances that they retained merely the memory of their former technology.45 As a result they were forced to build their houses completely of stone and turf. Because of the nature of these materials, the form of the house was modified. Since large stone houses were too difficult to build for this destitute population, they had to be satisfied with small ones.46 Yet despite these changes there is still an evident connection between these houses and the main type of large house. In its essential features, the small house resembles the large Greenland house. It is basically a miniature of this large house: the entrance is under the ground, the window is in the same place, the bench is raised in the compartments.47 Finally and most important, the house is often inhabited by several families. This, as we shall see, is the distinctive feature of a long-house.

This small stone house is, therefore, a transformation of the large house of Greenland and the Mackenzie region. Some archaeologists have, however, argued the contrary, namely that the small house was the prototype for the large one. The only evidence for this hypothesis is the fact that in north-west Greenland on the one hand, in Franz-Josef Land, Scoresby Sound48 and the Parry Archipelago49 on the other, old winter settlements have been found which appear to have consisted of small stone houses similar to those at Smith Strait. But this single piece of evidence is hardly convincing. Elsewhere there are numerous ruins of large houses. These houses are all relatively uniform50 and there is nothing to prove that these ruins are not, in fact, the oldest remains of winter houses that we possess. Furthermore, if the small house had been the initial form, it would be difficult to account for the generality and permanence, under various guises, of the large house type.51 One would have to claim that, at some specific but unspecified time and for equally unspecified reasons that are difficult to perceive, the Eskimo changed their winter settlement pattern from isolated families to a collective family structure. There is no plausible reason for this transformation, whereas we have shown how the reverse transformation can easily be explained in the case of the tribe at Smith Strait.

The contents of the house

Now that we know something about the arrangement of the house, we can consider the nature of the group living in it.

Just as the tent consists of a single family, so the winter dwelling, in all its forms, normally contains several families.52 We have already seen this from the previous discussion. The number of families who live together, however, is somewhat variable. There can be as many as six,53 seven or even nine families among the tribes of eastern Greenland,54 and formerly ten in western Greenland,55 though the number decreases to two for small snow-houses and for the tiny stone houses at Smith Strait. The existence of a certain number of families in the same house is so characteristic of Eskimo winter settlements that, wherever this begins to diminish, it is a sure sign that the culture itself is waning. Thus, in the census reports from Alaska, it is possible to distinguish Eskimo villages from Indian villages according to the number of families per house.56

In the Greenland house, each family has its own set place. In the igloo, each family has its own special bench;57 similarly, the family has its own compartment in the polygonal house,58 a section of a partitioned bench in houses in Greenland59 and its own side in the rectangular house.60 There is thus a close relationship between the structure of the house and the structure of the group that it shelters. It is interesting, however, to note that the space occupied by each family is not proportional to the number of its members. Families are considered as separate units, each equivalent to the other. A family consisting of a single individual occupies as much space as a large one comprising more than two generations.61

The kashim

Besides these private dwellings, there is another winter construction which deserves particular attention because it highlights particular features of Eskimo life during the winter season. This is the kashim, a European term derived from an Eskimo word meaning ‘my place of assembly’.62

The kashim, it is true, is no longer to be found in all areas. It is, however, still found throughout Alaska63 and among all the tribes of the western coast of America as far as Point Atkinson.64 According to the accounts we have of the most recent explorations, it is still found in Baffin Land, along the north-west coast of Hudson Bay and on the southern coast of Hudson Strait.65 Its existence was noted by the very first Moravian missionaries to Labrador.66 In Greenland, with one dubious exception,67 there is no trace of the kashim in the ruins of former settlements, nor is it mentioned by the early Danish writers; yet the kashim is still remembered in some Eskimo tales.68 There are good reasons, therefore, to regard it as a normal part of every primitive Eskimo settlement.

The kashim is an enlarged winter house. The connection between the two constructions is so close that the diverse forms of the kashim in different regions parallel the various forms of the winter house. There are two essential differences. First, the kashim has a central hearth, whereas the winter house does not, except in the extreme south of Alaska where the influence of the Indian house has its effect. This hearth is found not only where the use of firewood offers a good practical reason for its existence,69 but also in temporary kashim made of snow, as in Baffin Land.70 Second, there are usually no compartments, and often no benches but only seats, in the kashim.71 Even when it is built of snow and it is therefore impossible to construct a single large dome because of the nature of the material to hand, domes are joined together and walls are shaped to give the kashim the form of a large pillared hall.

These differences in the arrangement of the interior correspond to differences in function. There are no divisions or compartments but only a central hearth because the kashim is the communal house of the entire settlement.72 This, according to reliable sources, is where the ceremonies take place that reunite the community.73 In Alaska, the kashim is more specifically a men’s house,74 where adult men, married or unmarried, sleep apart from the women and children. Among the tribes of southern Alaska, it serves as the sweat-house;75 but this use of the kashim is probably relatively recent and of Indian, or even Russian, origin.

The kashim is built exclusively during the winter. This is itself good evidence that it is the distinctive feature of winter life. Winter is characterized by an extreme concentration of the group. This is not only the time when several families gather together to live in the same house, but all families of the same settlement, or at least the men of the settlement, feel the need to reunite in the same place to live a communal life. The kashim was created in response to this need.76

This discussion is intended to provide a better understanding of the seasonal arrangement of Eskimo dwellings. These are different in their form and dimensions and, as we have seen, they shelter groups of very different sizes. But their distribution is also very different in summer and winter. According to whether it is winter or summer, they are either gathered together or scattered over a vast territory. The two seasons present two entirely opposed appearances.

The distribution of winter dwellings

While the internal density of each separate house varies, as we have shown, according to the region, the density of an entire settlement is always as high as subsistence factors permit.77 The social volume of a settlement – the area actually occupied and exploited by the group – is kept to a minimum. Seal-hunting, which requires hunters to go out a certain distance, is carried out exclusively by men, and they do not proceed beyond the shore except for brief and limited purposes; and although the sled-trips undertaken mainly by men78 may be important, they hardly affect the total density of a settlement except when it becomes overcrowded.79

The same is true at Angmagssalik where the group is as concentrated as possible; there an entire settlement resides in a single house which, consequently, comprises all the members of the social unit. Although normally a house may have from two to eight families, the house at Angmagssalik has a maximum of eleven families with a total of fifty-eight occupants. Along the coast-line of 120 miles, there are, in fact, thirteen such settlements with thirteen houses. The 392 inhabitants of the region are divided among these houses, with an average of thirty people per house.80 This extreme concentration is not, however, the original situation but undoubtedly the result of an evolution.

In all other cases where scattered and isolated winter houses have been observed, they were apparently inhabited by families who, for various reasons, had separated from their original group.81 The ‘single houses’ observed by Petroff in Alaska82 seem virtually to disappear in Porter’s census; and, in any case, the first major census for this region – that by Glasunov in 1824 which was fortunately conducted during the winter – mentions only villages with eight to fifteen houses comprising 200 to 400 members.83 Among the ruins of the Parry Archipelago and of North Devon Island winter settlements are frequently found reduced to a single house, but this reduction, considerable as it may seem by comparison with average settlements, is hardly surprising in view of the fact that these ruins evidently date from a period when impoverished Eskimo were abandoning these regions.84

So we can say that, in general, once we have eliminated the seemingly contrary evidence, a winter settlement is composed of several houses near one another.85 These houses were not systematically arranged,86 except – as far as we know – for two cases among the southern tribes of Alaska.87 This fact is important.

This arrangement of dwellings is enough to demonstrate the concentration of the population at this period. But perhaps this concentration was once greater. Given the present state of our knowledge, this conjecture can hardly be rigorously proved, but it is certainly plausible. In fact, early English voyagers describe Eskimo villages dug into the earth like molehills, with all the huts grouped around a central hut that was larger than the rest.88 This was, in all probability, the kashim. On the other hand, for the tribes to the east of the Mackenzie, there are specific statements about communications between the houses and even between the houses and the kashim.89 Thus the winter group could be considered as having once consisted of a kind of large house that was both a single and a multiple unit. This would explain the formation of settlements later reduced to a single house, such as at Angmagssalik.

The distribution of summer dwellings

In summer, the distribution of the group is totally different.90 Winter density gives way to a contrary phenomenon. Not only does each tent contain only a single family, but these tents are greatly separated from one another. The gathering of families into one house and of houses into one settlement is followed by a dispersion of families; the group scatters. At the same time, the relative immobility of winter gives way to travel and migrations that are often quite considerable.

This dispersion takes different forms according to local circumstances. Usually, families spread out both along the coast and into the interior. In Greenland, with the sudden arrival of summer,91 families who were concentrated in the igloos of the settlement load the umiaks with the tents of two or three associated families. In a very short time, all the houses are empty and the tents are strung out along the shores of the fiord. They are ordinarily located at a considerable distance from one another.92 At Angmagssalik, opposite the thirteen winter houses (each of which, we know, forms a settlement), twenty-seven tents are scattered over the islands of the fiord; these are later moved to at least fifty different sites – the rare pastures where the reindeer graze (see Figure 5). According to Cranz’s superb reports,93 in the coastal area between the settlement of Neu Herrnhut and Lichtenfels there was just as great a dispersion; for eight settlements at most, there were no fewer than twenty-two halting-places and camp sites. And undoubtedly Cranz is mistaken in underestimating, rather than overestimating, their number. Besides the dispersion along the fiords,94 the Eskimo in Greenland also made trips to the grazing sites of reindeer and to salmon rivers.95 The same was true in Labrador.96

Figure 5 The winter settlements and summer settlements at Angmagssalik (Henri Beuchat).

This map is based on Holm (1894, p. 249). The contours of the coastlines of the fiords are still uncertain; see S. Rink (1900, pp. 22, 23 and 43).

We have good information on the expansion of the Iglulik in Parry’s time, thanks to excellent Eskimo maps which he published;97 these show the summer dispersion of the tribe. This small tribe stretches over a coastal area of more than sixty halting-places and even swarms inland along the rivers and lakes of the interior, with some families going in search of wood to the other side of the Melville Peninsula and right across Baffin Land. When one realizes that these seasonal migrations are undertaken by families and may require six to twelve days’ travel, it is apparent that this mode of dispersion implies an extreme mobility of groups and individuals.98 According to Boas,99 the Oqomiut, who live in the north of Baffin Land, crossed Lancaster Strait when the ice was breaking up and then went on up to Ellesmere Land as far as Smith Strait. In any case, it is certain that the former settlements in the northern part of Devon Island were equally widely dispersed; for eight winter settlements, there are ruins of thirty summer sites scattered over an immense coastline. These examples could be multiplied. Figure 6 shows the areas of dispersion covered by three tribes in Baffin Land.

All along the American coast,100 the same phenomena occur in varying degrees. The Point Barrow Eskimo attain the maximum distance in their two-stage trading expeditions: first they go to Icy Cape to obtain European goods; then they go to Barter Island to exchange these with the Kupungmiut Eskimo of the Mackenzie.101

The three deltas or the three estuaries are the only regions where patterns of dispersion are less than normal, but each of these exceptions is the result of particular chance circumstances which we can note. In the Mackenzie,102 the Yukon and the Kuskokwim regions, summer groups are relatively large. One account mentions 300 people from the Mackenzie tribe who gathered at Cape Bathurst.103 But this group, at the time it was observed, had gathered only temporarily; they had come together for an exceptionally abundant whale-hunt, of white whales in particular.104

Figure 6 Areas of the summer dispersion of the Akuliarmiut, the Qaumauang and the Nugumiut. Only winter settlements are shown; the two single triangles indicate the furthest locations of summer tents (Henri Beuchat).

At other times during the summer this same tribe was dispersed. It is also reported that, in certain villages of the Kuskokwim, the winter houses are occupied during the summer; but it seems clear that they are occupied only temporarily, when the group had gone to the sea to take part in exchanges, and then returned to disperse upstream to fish for salmon and later out onto the tundra to hunt reindeer and migrating birds.105 Elsewhere, especially in villages on maritime rivers, it happens that before abandoning the winter houses, the village sets up its tents or its winter houses in a regular order not far away.106 But there is a specific reason for this particular situation which includes the fact that the population density does not fall below its winter level:107 in both summer and winter, the group maintains virtually the same subsistence pattern based on a diet of fish. It is indeed interesting to note that, even in this awkward situation, a dual morphology persists, despite the fact that the group remains in one place and the reasons for its summer dispersion have disappeared.108

This summer dispersion must be considered in relation to an aspect of Eskimo collective mentality whose analysis provides a better understanding of what makes this summer organization so different from that of winter. Ratzel has distinguished between the geographical volume and the mental volume of societies.109 The geographical volume is the space actually occupied by a particular society; its mental volume is the geographical area that the society succeeds in encompassing in its thought. Thus there is a marked contrast between the modest dimensions of a poor Eskimo tribe and the immense stretches over which it spreads, or the enormous distances covered by central tribes in the interior.110 The geographical volume for the Eskimo is the area covered by their summer groups. But how much more remarkable is their mental volume, in other words the extent of their geographical knowledge. Instances of long trips undertaken by sledge before the melting of the snow in spring, by families in umiaks during the summer or by individuals in winter are not at all uncommon.111 As a result, the Eskimo, even those who have not made these trips, have a traditional knowledge of extremely distant areas; all explorers have relied on this geographical talent, with which Eskimo women are also eminently endowed.112 We ought, therefore, to consider Eskimo summer society not just as a society that extends over a vast area in which it lives and travels but as a society that thrusts well beyond this area families or isolated individuals – lost children, as it were – who return to their natal group when winter comes or during the next summer, having wintered where they could. One could compare these individuals with the long antennae extended forward by a creature that is itself extraordinarily distended.