WE WERE NEGOTIATING A large commercial agreement.1 The company I was advising was an early-stage venture that had developed a potentially game-changing product in a multibillion-dollar industry. The folks on the other side of the table were hoping to license our product and help bring it to market. As a result, we had to negotiate a wide range of issues: licensing fee, royalty rate, exclusivity provisions, milestones, development commitments, and so on. We got stuck on royalty rate—that is, the percentage of sale price they would pay us for each product they sold.

There had been some early discussions in which the two sides had very informally agreed that a 5% royalty rate was reasonable. As time went on, it seemed that we had slightly different interpretations regarding how this percentage would be applied. Our view was that 5% was low, but would be acceptable as the rate they paid to us initially. As the product gained traction and was validated by the market, we felt the royalty rate should increase to a more appropriate, higher level. We understood that our technology was still in a development phase, that early sales momentum might be slow, and that their heavy investments in manufacturing warranted a concession from our side.

Their perspective was quite different. They argued that because of their investments, the royalty rate should initially be close to zero; after two to three years, the 5% rate would kick in; and after that, royalty rates should go down, not up. Why should they go down, we asked? “Because in our industry, we always see royalty rates go down over time, not up. That’s just how it is,” they replied. After some further probing they provided additional rationale: “If we are selling more of your product over time, you should be willing to accept a lower percentage.”

Our initial hope was that we would be able to avoid confronting this issue head-on because the value of the overall deal was quite high, and with so much money to be made, this should not be a deal breaker for them. As the days passed with little progress, we realized that they really were stuck on the idea that “royalty rates are supposed to go down.” Were they worried about the precedent this might set in their other deals? Was it something they had promised their board, and now they did not want to lose face? Were they simply trying to get better financial terms? Try as we might, we could not get the numbers to work with rates going down over time. And if we tried to accommodate their desire for lower rates in the first year or two, it further increased our need for higher rates later. What to do?

There are times when two sides have incompatible positions and one has to yield. There are other times when each side compromises, meeting in the middle (for example, we could have agreed to a flat royalty rate over time). And then there are times when the laws of physics do not necessarily apply to negotiations: things can go up and down at the same time.

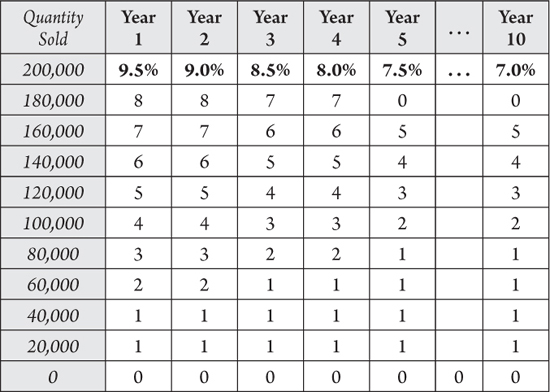

The breakthrough came when we noticed a flaw in how we were going about the discussion: we were stuck negotiating royalty rates in one dimension (over time), when our differing perspectives made clear that two dimensions were in play: the passage of time and the quantity of sales. Maybe we could leverage this to create a royalty schedule that went both up and down. If the other side needed to show rates going down over time, perhaps we could accommodate this and still safeguard our financial interests when the product sold more. With this in mind, we sent them a royalty table that no longer listed rates over time. Instead, we created a two-dimensional chart that listed rates as a function of time and quantity sold. It looked something like Table 1.2

TABLE 1

For each year, instead of one royalty rate we would have a range (with a minimum and maximum) based on quantity sold. Notably, the maximum royalty rate for each year would decrease over time (top row), which we hoped would meet their demand for diminishing royalty rates. At the same time, the actual royalty rate for each year could increase year after year if we sold more. Our expectations for how the royalty rates would actually materialize is shown in Table 2, with highlighted cells showing our internal projections.

It worked. The other side argued over some of the numbers in the table, but this new proposal helped reframe our dialogue and avoid impasse. The two sides were no longer arguing over royalty trajectory or the rationale for whether it should go up or down, and in the weeks ahead, the issue went away completely. The final agreement contained a simplified version of the royalty table (with fewer columns and rows) that accounted for time and quantity. While perhaps not substantively different from what could have been accomplished by agreeing to royalty rates on one dimension, this stylistic approach helped our negotiating partner feel more comfortable with how the deal looked, and let us feel comfortable with the financial outcome.

As this example illustrates, it’s not just what you propose, but how you propose it. Too often, negotiators incorrectly assume that if you get the substance of the deal right—that is, your proposal is sufficiently valuable to the other side—then you do not have to worry about “how it looks,” what we call the optics of the deal. But here, as in the NFL negotiations, the problem was not the value on the table, but the way the proposal was framed.

The role of optics is especially pronounced when there is an audience. The audience can be voters, the media, competitors, future negotiation partners, a boss, colleagues, or even friends and family. We are usually aware of our own audience, but we pay insufficient attention to theirs. In fact, their audience is just as important to consider as ours, especially if we are asking them to back down or make hefty concessions. To think of their audience as “their problem” ignores a central tenet of most difficult negotiations: there is no such thing as their problem; what seems to be their problem, if left unsolved, eventually becomes your problem. You may have already given them an offer that is superior to their alternatives, one that they “should” accept, but if you have not paid sufficient attention to the other factors that influence their decisions, you may find that even your generous offers are being rejected.

In the 1991 book Getting Past No, William Ury uses a cogent phrase to highlight the importance of helping the other side with its audience. Ury tells us to “write their victory speech” for them. I always ask my students and clients to carefully consider not just how much value they are providing to the other side, but also how they and their audience will view an offer. Think about how they can possibly say yes to what you are proposing and still declare victory. If you cannot think of a way that they can construe the agreement as a “win,” you may be in trouble.

This does not mean you should use stylistic or structural maneuvers to sell deals that are not in the best interest of either side’s constituents. Later in this section we will tackle the possibility and problems of doing so, but for now, let us appreciate how everyone can benefit from effective framing. In the NFL example, reframing the proposal using three buckets helped create a narrative that the parties could use when they went home with what quite likely was the best deal they were going to get. Reframing helped avoid an impasse that could have resulted from negotiators being too concerned about their own image rather than what was best for their constituents. In our negotiations over royalty rates we were able to come up with a substantive proposal that worked for the other side, but they still needed help in framing the proposal so that nonsubstantive concerns would not derail it.

The same principle applies in less complex environments—for example, when you are negotiating a job offer. If the hiring manager is going to sweeten the deal or make an exception for you, he or she will need some way to justify it internally. I always remind my MBA students to help the other side with the arguments and narrative they need to explain why the concession they made was appropriate and necessary in this case.

It is not always obvious whether the other side truly needs a substantive concession or merely has a problem with how your offer will look to their audiences. As you might also suspect, the other side is often unwilling to clarify which of these is the case. For them to admit that they don’t absolutely need a substantive concession would be costly if we were already prepared to make one. Telling us that our proposal is, in fact, sufficiently valuable also undermines their argument for making further demands. Finally, revealing that they need help selling the deal could make them look weak, and may disrupt the deal process. These are all understandable concerns that might cause someone who is struggling with the optics to act as if the deal is simply not good enough.

If there is sufficient trust in the relationship, the other side is more likely to be candid about what is really standing in the way of the deal. Even when there is little trust, a healthy degree of professional respect between the negotiators can help them signal to each other if they are stuck on the optics. Such signaling usually happens with a degree of plausible deniability; their signals will be ambiguous enough so that, if pushed, they can deny having such needs, but you know and they know that a message was sent.

It is important to remember that even these signals are hard to come by if you are seen as someone who always takes advantage of the slightest sign of weakness from the other side. To put it simply: The safer you make it for the other party to tell you the truth, the more likely they are to do so.3 The best way to make it safe is to show them, through your actions, that you do not exploit every advantage you see, and that you appreciate the risks they are taking in being honest or transparent on important issues. In my experience, repeated negotiations or multiple deals over many months or years are not required for such reputations to be built; reputations for integrity and reliability are usually built in countless small ways throughout the process of even one deal. For example, you build trust by reciprocating when others have shared sensitive information or made a concession, by following through on your commitments, and by showing a willingness to be flexible when possible rather than fighting tooth and nail on every point.

The royalty rate negotiation highlights a common problem in negotiations: getting stuck on one divisive issue. Counterintuitive as it may seem, negotiations are often easier when you have more than one thing to fight about. When there is only one issue on the table, and it is not easy to see how both sides can get what they want—or as much as they have promised to their audiences—you have a zero-sum problem in which at least one of you is going to feel or look like you lost. In these situations, it is useful to consider whether you can bring other issues to the table so that each side can walk away with something. When one of my children wants a toy that a sibling is playing with, I often advise him or her to bring along another toy to facilitate a potential trade. Arguing over who will get the one and only toy is not as likely to end well.

Alternatively, you might consider linking or combining what otherwise would have been two separate one-issue negotiations to create one easier negotiation rather than two more difficult ones. It is easier for my kids to agree on which TV show they will watch on Friday and Saturday if they discuss both days at the same time rather than having a separate conversation each day. What would be two separate arguments is replaced with one discussion in which each person gets something of value.

Sometimes, introducing even a relatively minor second issue is enough to dislodge the stalemate. The “win” you help to create for the other side need not always be as substantively valuable as what they give to you on the divisive issue. As noted, they may already be willing to live with you having your way on the divisive issue and are only looking for something—anything—around which to create a narrative that says “Both sides made concessions.”

Even if there are multiple issues in the negotiation, if I have to concede on the issue we are discussing now in the hope that you will concede on the issue to be discussed later, I may be unwilling to take that risk. To address such concerns, it is usually wise to negotiate multiple issues simultaneously. In other words, instead of trying to reach agreement one issue at a time, create the habit of making “package” offers and counteroffers. For example, “Here is what we can do on Issue A, here is where we need to be on Issue B, and here is what we can accommodate on Issue C.” This serves two purposes. First, as mentioned, it eliminates the risk that a concession made now will not be reciprocated later—you can make your concession contingent on theirs. Second, with multiple issues in the mix during the same discussion, it becomes easier for negotiators to make wise trades across issues—you can fight for what you care about more in exchange for giving up what the other side values more. In contrast, when you negotiate one issue at a time, people will often fight equally hard for whatever happens to be on the table at that time, making it difficult to find out what each side really cares about most.

For example, if I’m negotiating a complex business deal and someone tries to negotiate on one issue in isolation (e.g., price), I will usually shift the conversation to include other issues. There are many ways to do this. I can simply say that my position on price depends on where we are on other terms, so we need to discuss those issues as well before we try to finalize the price. I can make a “package” offer that includes terms other than price and clarify that my stated price assumes the following terms. I can present multiple offers, each with a different price and different terms, so the other side can better understand how the issues are related and how much flexibility I have. Any of these tactics can help us avoid getting bogged down on one divisive issue.

With multiple issues on the table, it is easier to construct an agreement that allows each side to show some wins. Unfortunately, even with multiple issues, one issue sometimes becomes the most prominent, and everyone starts using it as the sole measure of who wins and who loses. This was precisely the problem in the NFL negotiations; even if one side received monumental concessions on other issues, most observers would still use the revenue-split issue as the only barometer of success. We also see this when political parties are negotiating over legislation. The reason it happens can vary. Sometimes the media or other audiences have limited information or expertise to judge anything other than one prominent issue. Other times, regrettably, the negotiators themselves inflate the importance of a single issue in their rhetoric. Politicians might do this to drum up enthusiasm among supporters, or deal makers may inadvertently do so as they try to efficiently articulate their positions. In some cases the problem arises even when there is no audience; one issue becomes prominent because one or both sides have overstated its importance to justify an aggressive opening position.

Of course, there are situations where one issue is objectively the most important. And there are situations where, try as you may, no other issues are relevant (or possible to include) in the discussion. Even in these cases there is another strategy for avoiding a win/lose outcome: split the one issue into two or more. This is what the NFL negotiators did by splitting one revenue number into three separate revenue “buckets.” We did something similar in the commercial agreement discussion: splitting “royalty rate per year” into “royalty scale per year” and “royalty based on quantity.” And going back to the example of children and their toys: if there is only one toy, you might “split one issue into two” by discussing who gets the toy now and who gets it later. (Note: it is usually not as effective to actually break the toy into two pieces, although there are exceptions to this.)

What seems like one contentious issue is sometimes composed of multiple hidden interests that are reconcilable. In such situations, you may be able to overcome stalemate by unmasking the underlying interests. For example, consider an employee who is haggling over an increase in salary with an employer who is clearly unwilling to agree to the raise. The reason may be that the employer does not think the employee deserves such a large increase in pay. If so, one option would be for the two of them to “meet in the middle” and find an amount they can both live with. If they can’t find such a number, they may have to go their separate ways. But what if the employer thinks the employee’s demand is fair, and the only reason she is saying no to the initial ask is that her budget is limited for this year? In that case, instead of meeting in the middle, it may be wise to split the issue into “salary this year” and “salary next year.” This way, the employer can delay a hit to the budget, and the employee gets a much higher salary starting the following year.

In other words, it may be possible for both sides to meet their underlying interests (getting a higher raise, staying within budget), but this will only happen if they stop arguing about “what they want,” and start discussing their motivations for “why they want it.” This is referred to as shifting from positions (what people want) to interests (why they want it). Even when you have opposing positions on an issue, you might have compatible interests. The sooner you shift from arguing over positions to exploring underlying interests, the more quickly you will ascertain whether the needs of both sides can be reconciled.

Effective negotiators are assertive where needed and flexible when possible. After you have evaluated what each side brings to the table, and after you have considered what would be fair to demand, be as firm as necessary on what you deserve. But your assertiveness on substance should not spill over into stubbornness regarding how your demands are met. As the NFL and royalty rate examples demonstrate, the less demanding you are on the precise structure of the agreement, the more likely you are to find a deal that works for everyone. This flexibility gives the other side more options and makes it more likely that they can find some way to meet your needs. In my experience, a useful message to send to the other party, in both words and deeds throughout the negotiation, is this: I know where I need to get; I’m flexible on how we get there. To put it another way: the more currencies you allow them to pay you in, the more likely you are to get paid.

You may have noticed that our offer to negotiate royalty rates in two dimensions instead of one did not immediately solve the problem. Instead, the other side pushed back on elements of the structure and found faults with this proposal, not the least of which was the fact that the numbers were too high for them. But what the proposal did accomplish was getting us unstuck on the divisive issue. We were now discussing matters that were substantive and ultimately reconcilable. This is an important point: crafting proposals that are sensitive to the other side’s audience needs and which help to maneuver around divisive issues will not necessarily resolve the entire conflict or seal the entire deal. These proposals will, however, reduce the amount of time spent in deadlock and make it more likely that a mutually acceptable agreement can be found.

In the examples considered so far, deadlock was caused by the two sides having opposing objectives, which led them to make demands that seemed irreconcilable. But it is possible to have deadlock even when the interests of everyone in the room are aligned and everyone is working towards the same objective. People might still disagree about the best way to achieve that objective. This might happen because there is insufficient trust, or because people are not effectively articulating the merits of their proposals, or because everyone has strong, and different, prior beliefs about the right path to take. We will see a number of these factors at play in the next chapter, in a domain of human interaction that is quite different from the situations we have considered so far. Let’s see how framing tactics can help overcome psychological resistance to ideas that are new, foreign, or different from a person’s existing beliefs or expectations.