Product UG* and Critical Visioning in Communication Studies

“We are forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.” The IWW Preamble (Industrial Workers of the World, also known as the “Wobblies”) trumpets a utopian dream, wherein worker-run shops move society from an exploitative, profit-driven order to one of economic justice. Calling for “one union of all workers,” the Wobblies were one strand of a historic radical-left continuum within the U.S. labor movement that clashed with a conservative “business unionism” that has become the unquestioned norm of management-worker relations.

For the Wobblies (1905–1924), the building of worker solidarity toward the overthrow of capitalist economic domination included a vision of full societal-human emancipation and equitable sharing of wealth. In contrast, the business union model is critiqued for instilling a narrow economism within the working class. Such accommodationism gained total ascendency during the McCarthy era, when leftist elements in mainstream trade unions were viciously expelled. As a labor aristocracy aligned its interests with U.S. imperialist global domination, a George Meany-styled, anti-communist union hierarchy swapped cigars with management to keep industrial workers in place. For business unionism, the goal of labor solidarity is not the eventual emancipation of all workers, but rather, narrow materialist rewards that keep workers complicit collaborators with capitalist values of competition and self-interest; a union contract means economic advancement for individuals covered by the contract, not expansion of resources for the collective betterment of all working people.

Though now rarely heard, this radical labor perspective draws from homegrown socialist principles to advance a transformative egalitarian vision that applies principles of democracy to the economy. Today’s normative labor model is hierarchical and inertial, essentially accepting the rule of capitalist structural inequality. Though organized labor may wrestle some concessions from the capitalist class, workers themselves are basically aligned with a survival-of-the-fittest ideology.

This tension pulses through communication studies (and related social science and humanities disciplines) and its academic workers. On the one hand, the field has been strongly impacted by a range of theorists (Bourdieu, 1977, 1991; Castells, 2000, 2007; Fiske, 1987, 1989; Foucault, 1965, 1970, 1972, 1977; Habermas, 1971, 1984; Hall, 1979, 1980a, 1980b, 1980c; Radway, 1984, 1986) working radical critiques that have flowed through Marxist thought. This includes the Frankfurt School and Gramsci, with critical turns fired by the political and social movements of 1960s and 1970s—anti-racism, anti-imperialism, feminism, environmentalism, and queer pride.

Yet from graduate school to conference presentations, classroom lectures, and publications, the labor process (training and production) renders the relationship to such social criticism fundamentally academic in the sense of being abstract and disconnected from any real, direct political engagement. Certainly, some socially conscious academics embrace the challenge of praxis through varied means: action research, community-based learning, producing scholarship with community organizations, writing for popular publications, speaking out as public intellectuals. Yet in general, communication academics do not learn, nor are they expected to seriously engage with, the challenge of integrating theory and practice. This leaves a vast chasm between the political social-action implications of the critical theory we teach, and the hierarchical, disciplinary, and at times, oppressive labor processes we accept and reproduce.

If we consider ourselves workers, what do we produce, and how? If our notion of labor includes the goal of worker solidarity, which side are we on?

I will focus on the inequitable hierarchy in the labor relationship of instructor to student, particularly in terms of the production of the communication undergraduate as an intended worker in the communication industries. Higher education plays a key role in feeding workers to communication industries. Faculty silence on the shrinkage of the job market—to students, colleagues, and administrators—functions as a form of complicity with wider neoliberal strategies of labor exploitation.

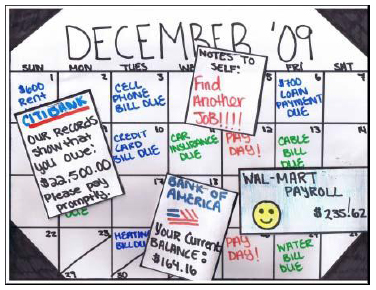

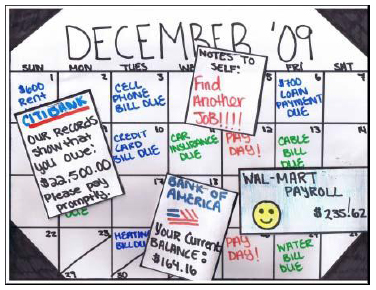

Especially at public colleges and universities buckling under the pressures of privatization, all faculty draw their salaries from a pot that is increasingly fed by student fees (Clawson & Page, 2011, p. 27; Folbre, 2010, pp. 46–47). Given the average $24,000 debt load for a 2010 U.S. college graduate (Lewin, 2011), and the scarcity of well-paying entry level positions in most professions, the typical college senior will be saddled with considerable monthly interest-incurring payments for many years to come.

Erin Curran Fall 2008

Student activists and others characterize the status of this debt-ridden generational cohort as one of indentured servitude. Though the agents to which they are contractually obligated are banks, the financial aid bureaucracy masks the exchange relationship between faculty services and the onerous debt the typical undergraduate incurs. In seeking an upwardly-mobile occupation, undergrads are loaned a certain amount of money for room and board; in exchange, they will work for many, many years to pay the salaries of the instructors who provide proprietary knowledge to inform a professional career.

Communication seniors are part of a much wider cohort that is facing a tough job market. 2009 Labor Department data indicates that 22.4% of all college graduates under 25 were unemployed; 22% were working jobs that didn’t require a college degree—meaning that, for nearly half of all graduates, at least on a vocational level, a college degree isn’t paying off (Rampell, 2011). While I have, as yet, found no hard data quantifying the market for entry-level communication-related jobs, anecdotal evidence is rather pessimistic. In a unit I teach on “Generation Debt” (Kamenetz, 2007), learners interview their fellow students on the employment and economic situation they are facing. Over the past three years, in classes made up mostly of seniors, few are graduating with expectations of landing a communications-related job. The following narrative is from a 2009 graduating senior:

I am feeling the utmost financial pressures and strains. My parents are divorced, and being on my father’s side of the agreement places me under his financial support. He, too, is enduring severe economic problems. He lost his job of almost twenty years, and can barely make ends meet. He helps me when possible, but I almost completely support myself. I have been able to attend college because of financial aid, but it does not cover all of my expenses. I have to work double shifts on the weekends in order to pay for my rent, food, clothing, school fees, and other life necessities, all of which really add up. Between classes Monday through Friday, and working 25 hours between Saturday and Sunday, I am completely exhausted and drained. Financial burdens have also forced me to take out a credit card, which I am also in debt with. I have always been an over-achiever, graduating high school a year early and now college a semester early, but recently I have had a hard time primarily focusing on my schoolwork. I simply do not have the time I want and need, nor the energy, to work to my full potential. This also leaves me feeling dissatisfied with myself. I also do not have time for a social life, whether it be because of schoolwork, work, or just the energy to do anything. I am worried about finding a stable, salary-based job post-graduation. Everyday I feel anxieties and worries over money, whether or not I can make rent, pay my bills, etc. I also cannot imagine ever being in a stable economic situation.

Students are particularly indignant over career “internships” that have become de rigueur in a communication major’s college experience. As documented by Ross Perlin (2011), college interns have become a major source of unpaid, entry-level labor—and may be a violation of federal fair labor practices. As the job markets in communication fields have contracted, and as the number of skilled, but un- or underemployed laborers continues to rise, such employers seem quite willing to exploit naïve undergrads by tempting them with implicit promises of post-graduation employment.

The problem is worst in the so-called “glamour” fields: journalism, the nonprofit world, government, the arts and entertainment—the very areas with the most influence on our culture and social policy. These are where the competition is highest and internships are the least likely to be paid. And because they are unpaid, only those with money can afford to take them. (Rheannon, 2011)

From what students report, their hopes often don’t play out, as corporations fill such positions with yet another round of bright-eyed interns. Such internships reinforce class inequities. Some of the most sought-after internships in TV, film, advertising, and public relations are in high-priced cities like New York and Los Angeles. As stipends are generally no longer provided, only those coming from more affluent families can, with parental subsidy, meet the high-priced urban living costs. Those saddled with debt and the responsibility to pay their own way can’t afford such luxuries. “That’s leading to a pernicious class bias, unfairly disadvantaging talented job aspirants from the middle and working classes. Perlin links the practice to the widening social inequality in America” (Rheannon, 2011).

In classroom discussions around this issue, the tone of some students is bitter; especially when jobs aren’t forthcoming, they justifiably perceive the whole internship process as a scam—including the Department of Communication as co-conspirators. Faculty and departmental staff help to facilitate and provide academic credit for such internships. Clearly, incredible learning may come from such direct vocational experience. Yet with corporate cost-cutting strategies squeezing the most labor from a leaner work force, communication departments become uncritical collaborators in a practice that directly contributes to the declining entry-level job market for undergrads. While I’m not sure exactly how we might play a role in advancing more equitable internship labor practices, the first step requires academics to acknowledge this exploitative dynamic, and to dialogue on measures we might take to reform such practices.

As colleges and universities pursue ever-more aggressive marketing campaigns to entice all possible enrollees, the premise underlying higher education is that a college degree will pay off. The highly demanding work load and the ideology of faculty professionalism seem to distance professors from feeling responsible for such claims. Yet the fact is, we are the direct, face-to-face intermediaries dispensing the raw materials (curriculum, instruction, grades) that lead to the final product of a degreed undergraduate. We provide the most important component in the assembly line. We are key fabricators in a factory whose product no longer commands quality value in the marketplace.

From what I observe, there is little departmental attention—from informal conversation to faculty meeting concern—focused on the urgency of the economic situation our students will encounter. Having been through multiple job interviews with no success, one student confided that she was “terrified” by the economic picture she was about to face.

Faculty disconnect from any political relationship to the product outcome extends across higher education. Of many inequities we may daily witness but have somehow learned to repress (“strategic denial” is a term offered by a colleague to characterize this process), the immediate and long-term economic hardships facing our students is one of many systemic dysfunctions to which we close off cognitive-emotional response. This cut-off valve that filters the institutional vision of the professional-managerial class seems a part of the internalized enabler of the disciplinary regime.

While academic cohorts in Puerto Rico, Britain, Spain, France, Germany, and Greece have joined the massive popular opposition protesting the global neoliberal austerity assault, aside from a few notable instances (e.g., Wisconsin), we are part of a quiescent, compliant professional-managerial class. For academics in communication studies who work from a critical perspective, there’s a serious gap between the scholarship and teaching that is the product of our labor and the lack of direct engagement with the immediate assault on all workplaces—ours included.

Key elements of the neoliberal assault—slashing the public sector, including aid to higher education, attacks on workers rights, outsourcing, the move to contingent labor—all directly affect the institutions, work conditions, and income of academic labor (full-time faculty to undergraduates). The crisis of youth un- and underemployment is but one urgent sign of the failure of capitalist ideology as it worships the magical wonderdust of the marketplace.

The question of resistance by those directly affected—including the young people we teach—is critical. From what I observe, study, and take in from student classroom dialogues, the corporate-dominated communication order about which communication professors study and teach, is a primary force of political obfuscation and pacification. Accounting for the glaring contrast between the impassioned outrage of youth in the Middle East and Europe against regimes and policies that are squeezing their life possibilities and the silence of youth in the U.S., Giroux notes the pernicious grip of corporate culture:

In a social order dominated by the relentless privatizing and commodification of everyday life and the elimination of critical public spheres, young people find themselves in a society in which the formative cultures necessary for a democracy to exist have been more or less eliminated, reduced to spectacles of consumerism made palatable through a daily diet of game shows, reality TV and celebrity culture. . . . Instead of public spheres that promote dialogue, debate and arguments with supporting evidence, American society offers young people a conservatizing, deformative culture through entertainment spheres that infantilize almost everything they touch, while legitimating opinions that utterly disregard evidence, reason, truth and civility. (2011, p. 10)

Some of us use the term “predatory” to characterize the marketing attack on the youthful consumer. I perceive a dangerous relationship: Youth purchases fund the entertainment industries which, in turn, inject an opiate of mindless pleasures that block out critical voices, information, and models of resistance. This question of the political numbing of youth by the cultural industries is a topic that falls directly within the purview of communication studies. The objects we instruct are the very agents who are subject to this submission—and could be engaged in a dialogue and participatory action research to discern this question of critical consciousness by youth in relation to attachments to corporate culture.

It is for communication academics in communications studies to detail, describe, analyze, and interpret this conundrum. How can we bring these very immediate, pressing concerns to our classrooms?

Communication studies faces a dilemma. On the one hand, the economic downturn has made it ever harder for communication graduates to find entry level jobs in the media industries. The degrees we proffer have diminished value in the marketplace. On the other hand, regardless of the critical perspectives we impart, we are essentially preparing students to take their place as operatives of a cultural environment dominated by a corporate oligopoly that produces hyper-commercialized ideology and an all-pervasive matrix of consumer culture that is not neutral, but as evidenced by multitudes of communication scholars in our field, has enormous harmful impact. Do we really believe our students should be doing the dirty work of these industries?

Real-life questions about the ethics of working in a profit-driven communication order seem absent. For those of us who believe that corporate profit should not be the driving motive, then what should be the basis for creating shared stories, symbols, songs, games, information, and social relations? Who will do this labor? How will it get funded? How and where might communication undergraduates get jobs? Engaging such questions as a fundamental part of our academic labor means seeing our work as visioning what a new communications order would look like—as the Wobblies put it, “forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.” It means transforming our individual and collective work identities from those of academics who are politically silent, to those of public intellectuals asserting our rights to democratic participation in the operation of the communication industries. For a faculty meeting agenda item, I want to include the question: What blocks the capacity to see beyond existing power structures to envision a media system guided by principles of democracy and the public interest? Should this problematic be embraced as part of the labor of being a communication academic?

There is an inherent challenge in seeing beyond the present to a transformed future. In the only mass communication textbook I’ve thus far come across that addresses this issue, Lazere discusses the problem of “limited imagination” from a leftist perspective:

Perhaps the most profoundly conservative force in all of the cognitive patterns discussed here is their potential for inhibiting people from being able to imagine any social order different from the established one. The present reality is concrete and immediate, alternatives abstract and distant . . . . What is at issue is the hypothesis that people’s loss of capacity to imagine things being any different than they are could preclude their supporting changes that would in fact be strongly in their interests. (1987, p. 413)

I believe the horse blinders restricting our capacity to imagine a different future are compounded by the demonization of socialist thought in the United States. In this country, children do not grow up with accurate information about the nature of the capitalist political economy that exercises inordinate influence over virtually every aspect of our living, breathing reality: work, income, housing, family possibilities, school, media, food, fashion, transport, language, leisure, healthcare, ideology. Rather, this reality is normalized, naturalized—always has been, always will be. Like the air we breathe, it’s seemingly invisible, but all-pervasive.

When one grows up without access to certain terms and concepts that connect with a larger critical discourse (in this example, socialist thought), then for the rest of one’s life, cognitive resources to understand and name capitalist oppression are unavailable. The complete absence of a critical public discourse about capitalism is reinforced by the ever-circulating negative ideology that associates the words “socialism” and “communism” with all that is evil and anti-American. Though “better dead than Red” is of an earlier era, current attacks on Obama as a “secular socialist” indicate that the Bolshevik bogeyman is still very much alive and well (CBS News, 2009; Gringrich, 2010). To put forward democratic alternatives to the corporate media oligopoly seems far-fetched, indeed, utterly impossible.

Many faculty in the department where I teach convey strong critical perspectives on the media industries—points of view that are clearly critical of corporate commercial hegemony. As most students have not been previously exposed to this kind of critique, the process for them can be highly transformative, demystifying ideological messages that the learners had never before considered. Yet there’s a problem if only negative criticism is presented. From what my students tell me, the range and reinforcement of critical analysis they receive contributes not to a sense of empowered agency, but rather, to cynicism and hopelessness. A course I teach on “Youth, Democracy, and the Entertainment Industries” (Comm. 397ss, UMass-Amherst) challenges learners to consider what a democratic media system would look like. I ask whether they’ve done critical visioning in other classes. Except for rare instances, the curriculum trajectory seems to feature almost exclusively negative analysis without offering equal weight to questions of democratic alternatives.

In Das Kapital, Marx offers a stunning analysis of the productive-exploitative machinations of mid-19th century European capitalism. In his dialectical imagination, the historical conflict of past and present, thesis-antithesis, bursts open a new stage of historical possibilities. Obviously, the metaphysical (“scientific”) futuristic fantasy formula of thesis-antithesis-synthesis is simplistic and mechanistic, and has been quite faulty in charting the course of working-class struggle. But what is worth considering in the dialectical model is the pairing of critical analysis with transformative visioning. Beyond detailing the pathology down to its root causes, the doctor must do more than simply assess. Without Rx, the subject doth perish.

Compounding the absence of pedagogy advancing visions of a democratic economy is the reality that most students in department where I teach want to work in fields that are the subject of our wholesale critique: multiple sectors of the entertainment industries (sports, TV, film, fashion, music), advertising, marketing, (Big Pharma, too, seems to be one place students are still finding jobs) and public relations. Though I have no doubt that they take the varied critiques to heart, it is highly unlikely that they would even consider the project of subversion from within. Why should they? Most classes they take do not address the challenge of how to transform the media industries toward principles and practices that might balance the relentless drive for profits with the public interest. Though we may teach from a critical perspective, we are less likely to provide scaffolding that moves from critical analysis to critical communication activism. We question important aspects of the media industries, yet most of us are unlikely to advocate plans of radical transformation.

This critique may be illustrated through comparison with the see-no-evil approach taken by the UAW (United Auto Workers) toward the production of ever-bigger gas guzzlers. For all these years, the union has essentially closed its eyes to the ethical-ecological impact of the auto-industrial complex: making us an ever-more atomized, consumerist culture; mandating murderous imperialist war for oil; and hastening climate change and environmental devastation, as with the Deepwater Horizon disaster. Rather than advocating the reshaping of U.S. transportation policy toward an approach that would serve the widest public good, the UAW hitched its wagon to a logic that maximized short-term profits over long-term public interest. One wonders whether, instead of overseeing the massive reduction of its workforce and the cutting of wages and benefits, the UAW might have been able to spearhead changes in U.S. transportation infrastructure that would have kept its members employed by building technology to revitalize a public transit system dismantled by the auto companies after WW II—trains, trams, trolleys, and who knows what else?

Though communication academics are not directly on the assembly line producing commercialized corporate culture, we criticize from afar without taking any professional responsibility for developing pedagogy, scholarship, and departmental and discipline-wide approaches to praxis that take on the corporate behemoth. This question of what we, as scholars and teachers, might do to actively resist this wholesale degradation of our cultural environment is not a topic I’ve ever heard openly discussed; nor have I seen it as an agenda item at faculty meetings. As scholar-teacher-critics of the media industries, what else do WE have to offer?

In Comm. 397ss, we consider the premise that the revenue generated by the entertainment industries draws heavily from the purchases made by young people and their parents: toys, video games, electronics, mobile devices, fast food, sports, fashion, movies, music, etc. Invoking principles of democracy, I pose this question to students: Since you’re providing a significant chunk, if not the majority, of the cash that makes these industries run, should democracy entitle some voice and vote in the production apparatus (jobs) and media content (narrative-iconic representation) you pay for?

Radicalizing the agenda of workers in communication studies—including students as essential players in the visioning—means taking up the question of the enormous wealth generated by the communication industries: How and from whom does this money come, with what impact, and what do we actually get back in terms of serving the common good? I am arguing that principles of democracy extended to the communication industries should give workers/consumers the right to participate in decisions that determine the ways in which popular culture is produced and distributed—and the jobs that make it flow. Can our students be engaged in a dialogue visioning roles they might play in a cultural landscape that seeks to serve the creative needs of youth and others—without profit as the driving force?

There are some heroic, David vs. Goliath projects spearhead by public scholars that have earned notable victories. Susan Linn of the Campaign for a Commercial Free Childhood continues to win battles against the likes of Disney and Scholastic Books (Linn, 2011). McChesney was instrumental in launching Free Press (Free Press, 2011). Jeff Chester of the Center for Digital Democracy is vigilant on the front lines, circulating alternative policy perspectives to the corporate thumb on government to turn the (relative) freedom of the Internet over to the profit motive (Center for Digital Democracy, 2011). Sut Jhally (2011) continues to produce cutting-edge media analysis that translates scholarly critique to wider publics through accessible documentary forms. These efforts demonstrate the real power of communication scholars as public intellectuals. Yet as the output of very strong individuals, these achievements don’t offer a viable grassroots, collective model of how academic laborers at all levels of the academic hierarchy may come together to shape a pedagogy of praxis that includes visioning and direct engagement toward the creation of a democratic media economy.

Though in research and instruction, faculty are more likely to labor as individuals (implicitly in professional competition), this move calls for a collective commitment. The end goal of societal transformation—political, economic, cultural, personal—transcends the labor of personal advancement to work with colleagues for the advancement of the common good, public rather than private gain. It requires a radical shift in consciousness to see ourselves not merely as scholars and teachers critiquing the status quo, but as skilled laborers shaping a democratic communication order. What would it look like for communication instructors to join with our undergrad and graduate students in this kind of visioning dialogue—not merely as an academic exercise, but with full-scale intentions of mapping out and advocating for a radically different, democratic communication order?

In my classes, I point to some historic and contemporary examples of possible alternative cultural production models. In the United States, there are the varied arts programs that flourished, if only for a brief period, under the New Deal’s WPA: the Federal Theater Project, the documentation done by photographers under the F.S.A, the Federal Writers Project (which included a radio component). Though all of European public TV is under assault, there’s still the BBC and Channel 4, and government funded, noncommercial TV thrives in many European nations. Van Jones has outlined a vision of a “green collar” economy and calls for a movement to rebuild the American dream through new WPA-like initiatives (Abbruzzese, 2011; Kolbert, 2009). We need to add our blueprints which include funding jobs to support the expansion of public media resources, networks, and production jobs for youth in schools, communities, local and state governments, and small and regional businesses.

Yet it seems we’ve completely abandoned the many historical mandates that view the airwaves as a public trust. We’ve let the handful of corporations that control most media in this country (and the world) completely off the hook in their public service obligations. In marches and rallies, the National Nurses Organizing Committee has vigorously advocated a tax on all Wall Street financial exchanges as a solvent to the national deficit and the source of revenue for single-payer health (National Nurses United, 2011). We, too, should be advancing public campaigns for a tax on all advertising revenue to support public media on national, regional, and local levels. Similar public youth media funding expectations should be extended to Comcast, Disney, Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, McDonald’s, Verizon, ATT, Blackberry (RIM), and all the other communication industry titans that derive prominent, if not predominant, revenues from youth and their families.

This direction calls for tremendous courage propelled by righteous indignation toward the takeover of our culture by selfish, greedy oligarchs—and wonders why we’ve essentially given up this fight. I feel both anesthetized and livid at how degraded we’ve let the situation become in contrast to the tremendous potential for creativity, imagination, education, and healing transformation that could occur through media channels which are completely fueled by our purchases.

It seems that the effects of cutbacks and the nonstop speed-up (in disbelief, a colleague recently related the term “time deepening” that’s being used in faculty time-management workshops as a strategy to get more productivity out of each minute) make it hard for faculty to consider all but the straight and narrow. Facing the students we produce as laborers—who may or not get jobs—the question of “which side are we on?” challenges us to consider the fundamental nature of materialist ideology as it guides our agency within regimes of control and discipline. As teachers, researchers, and scholars, what is our capacity to envision and make the labor of communication studies the project of human economic and social justice?

Abbruzzese, J. (2011, June 24). Van Jones kicks off American dream movement with energetic rally and speech at NYC’s Town Hall. AlterNet. Retrieved from http://www.alternet.org/story/151418/van_jones_kicks_off_american_dream_movement_with_energetic_rally_and_speech_at_nycs_town_hall_

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power: The economy of linguistic exchange (G. Raymond & M. Adamson, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Castells, M. (2000). The rise of the network society. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Castells, M. (2007). Communication, power and counter-power in the network society. International Journal of Communication, 1, 238–266.

CBS News. (2009, July 22). Steele calls Obama health plan “socialism.” Retrieved from http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2009/07/20/politics/main5174417.shtml

Center for Digital Democracy. (2011). Protecting privacy, promoting consumer rights and ensuring corporate accountability. Retrieved from http://democraticmedia.org

Clawson, D., & Page, M. (2011). The future of higher education. New York: Routledge.

Fiske, J. (1987). Television culture. London: Routledge.

Fiske, J. (1989). Understanding popular culture. Boston: Unwin Hyman.

Folbre, N. (2010). Saving state u: Why we must fix public higher education. New York: The New Press.

Foucault, M. (1965). Madness and civilization: A history of insanity in the age of reason. New York: Times Mirror.

Foucault, M. (1970). The order of things: An archaeology of the human sciences. New York: Vingate.

Foucault, M. (1972). The archaeology of knowledge and the discourse on language. New York: Pantheon.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. London: Allen Lane.

Free Press. (2011). About us. Retrieved from http://www.freepress.net/about_us

Gingrich, N. (2010). To save America: Stopping Obama’s secular-socialist machine. Washington DC: Regency Publishing.

Giroux, H. (2011, February 28). Left behind? American youth and the global fight for democracy. Truthout. Retrieved from http://www.truth-out.org/print/290

Habermas, J. (1971). Knowledge and human interests. Boston: Beacon.

Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action. Boston: Beacon.

Hall, S. (1979). Culture, the media and the “ideological effect.” In J. Curran, M. Gurevitch, & J. Woollacott (Eds.), Mass communication and society (pp. 315–348). Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE Publications.

Hall, S. (1980a). Cultural studies and the centre: Some problematics and problems. In S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, & P. Willis (Eds.), Culture, society and the media (pp. 15–47). London: Metheun.

Hall, S. (1980b). Introduction to media studies at the centre. In S. Hall et al. (Eds.), Culture, society and the media (pp. 117–121). London: Metheun.

Hall, S. (1980c). Encoding/decoding. In S. Hall et al. (Eds.), Culture, society and the media (pp. 128–138). London: Metheun.

Jhally, S. (2011). Sutjhally.com. Retrieved from http://www.sutjhally.com

Kamenetz, A. (2007). Generation debt: How our future was sold out for student loans, credit cards, bad jobs, no benefits, and tax cuts for the rich geezers—And how to fight back. New York: Penguin Group.

Kolbert, E. (2009, January, 12). Greening the ghetto. The New Yorker. Retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2009/01/12/090112fa_fact_kolbert

Lazere, D. (Ed.). (1987). American media and mass culture: Left perspectives. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Lewin. T. (2011, April 11). Burden of College Loans on Graduates Grows. The New York Times. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com/2011/04/12/education/12college.html

Linn, S. (2011). Consumingkids.com. Retrieved from http://www.consumingkids.com

National Nurses United. (2011). Time for a main street contract: Heal America/tax Wall Street. Retrieved from http://www.nationalnursesunited.org/affiliates/entry/msc1

Perlin, R. (2011). Intern nation: How to earn nothing and learn little in the brave new economy. New York: Verso.

Radway, J. (1984). Reading the romance: Women, patriarchy and popular literature. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Radway, J. (1986). Identifying ideological seams: Mass culture, analytic method, and political practice. Communication, 9(1), 93–123.

Rampell, C. (2011, May 18). Many with new college degree find the job market humbling. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/19/business/economy/19grads.html

Rheannon, F. (2011). The corporate social irresponsibility of the internship phenomenon: An interview with Ross Perlin. Retrieved from http://ecoopportunity.net/2011/05/the-corporate-social-irresponsibility-of-the-internship-phenomenon

_________________________

*For this article, UG refers to an “undergraduate.”