Anonymous

One of the most universally studied of the English classics, Beowulf is considered the finest heroic poem in Old English. Written ten centuries ago by an anonymous Anglo-Saxon poet, it celebrates the character and exploits of Beowulf, a young nobleman of the Geats, a people of southern Sweden. The exact date of the composition of Beowulf is a matter of debate among scholars; it has been established that the oldest surviving manuscript was produced between 975 and 1025 A.D. The text includes echoes of actual historical events from several centuries before those dates.

Beowulf rescues the royal house of Denmark from marauding monsters, then returns to rule his people for fifty years, ultimately losing his life in a battle to defend the Geats from a dragon’s rampage. After his death, his body is cremated and a tower is erected in his memory. The poem combines mythical elements, Christian and pagan sensibilities, and actual historical figures and events in a narrative that ranges from vivid descriptions of fierce fighting and detailed portrayals of court life to earnest considerations of social and moral dilemmas. Originally written in Old English verse, the complete text is presented here in an authoritative prose translation by R. K. Gordon.

Lo! we have heard the glory of the kings of the Spear-Danes in days gone by, how the chieftains wrought mighty deeds. Often Scyld-Scefing wrested the mead-benches from troops of foes, from many tribes; he made fear fall upon the earls. After he was first found in misery (he received solace for that), he grew up under the heavens, lived in high honour, until each of his neighbours over the whale-road must needs obey him and render tribute. That was a good king! Later a young son was born to him in the court, God sent him for a comfort to the people; He had marked the misery of that earlier time when they suffered long space, lacking a leader. Wherefore the Lord of life, the Ruler of glory, gave him honour in the world.

Beowulf, son of Scyld, was renowned in Scandinavian lands—his repute spread far and wide. So shall a young man bring good to pass with splendid gifts in his father’s possession, so that when war comes willing comrades shall stand by him again in his old age, the people follow him. In every tribe a man shall prosper by deeds of love.

Then at the fated hour Scyld, very brave, passed hence into the Lords protection. Then did they, his dear comrades, bear him out to the shore of the sea, as he himself had besought them, whilst as friend of the Scyldings, loved lord of the land, he held sway long time with speech. There at the haven stood the ring-prowed ship radiant and ready, the chieftain’s vessel. Then they laid down the loved lord, the bestower of rings on the bosom of the barge, the famous man by the mast. Many treasures and ornaments were there, brought from afar. I never heard of a sightlier ship adorned with weapons of war and garments of battle, swords and corslets. Many treasures lay on his bosom that were to pass far with him into the power of the flood. No whit less did they furnish him with gifts, with great costly stores, than did those who sent him forth in the beginning while he was still a child alone over the waves. Further they set a golden banner high over his head; they let the ocean bear him; they surrendered him to the sea. Sad was their mind, mournful their mood. Men cannot tell for a truth, counsellors in hall, heroes under the heavens, who received that burden.

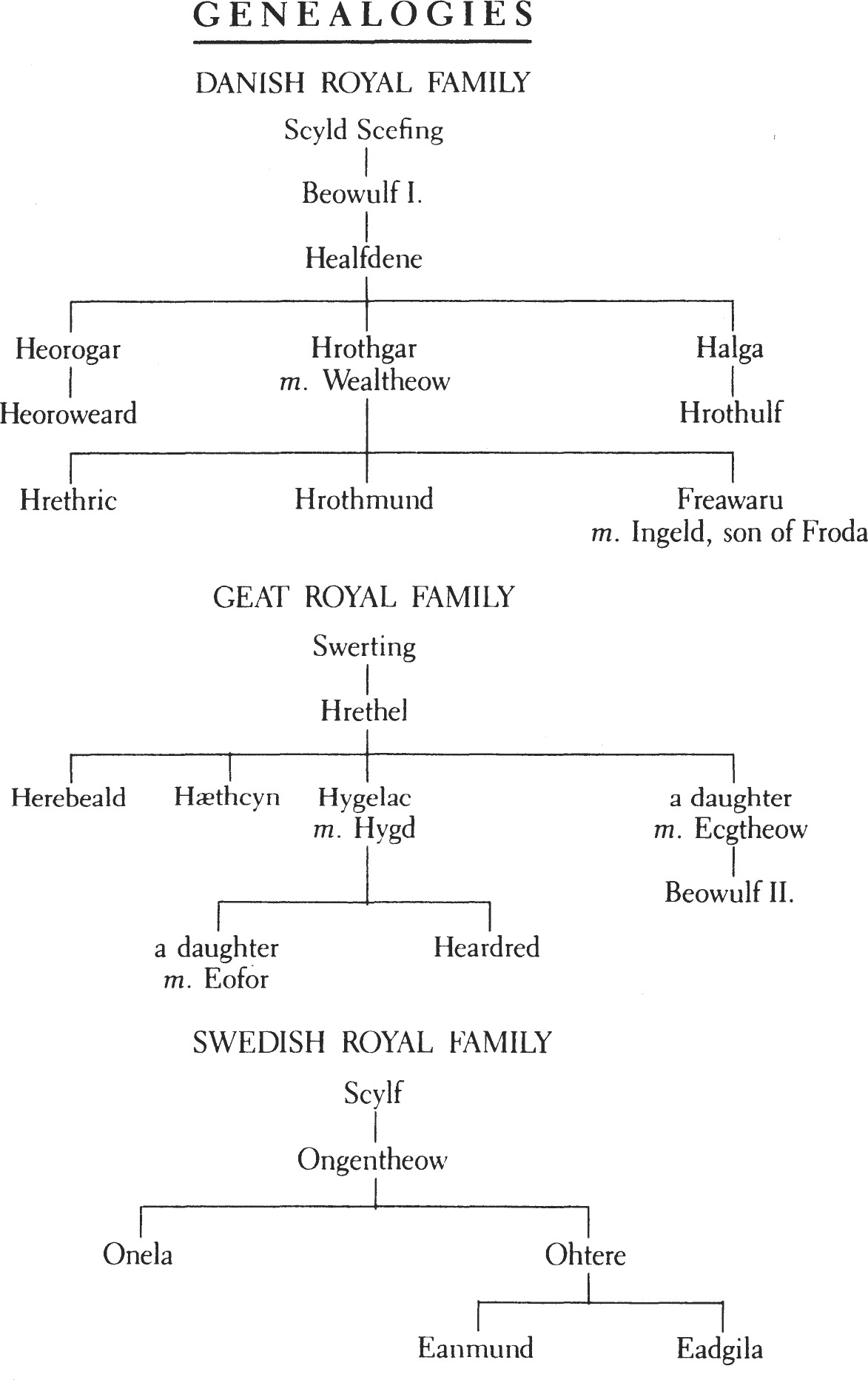

Then Beowulf of the Scyldings, beloved king of the people, was famed among warriors long time in the strongholds—his father had passed hence, the prince from his home—until noble Healfdene was born to him; aged and fierce in fight, he ruled the Scyldings graciously while he lived. Four children sprang from him in succession, Heorogar, prince of troops, and Hrothgar, and Halga the good; I heard that Sigeneow was Onela’s queen, consort of the war-Scylfing. Then good fortune in war was granted to Hrothgar, glory in battle, so that his kinsmen gladly obeyed him, until the younger warriors grew to be a mighty band.

It came into his mind that he would order men to make a hall-building, a mighty mead-dwelling, greater than ever the children of men had heard of; and therein that he should part among young and old all which God gave unto him except the nation and the lives of men. Then I heard far and wide of work laid upon many a tribe throughout this world, the task of adorning the place of assembly. Quickly it came to pass among men that it was perfect; the greatest of hall-dwellings; he whose word had wide sway gave it the name of Heorot. He broke not his pledge, he bestowed bracelets and treasure at the banquet. The hall towered up, lofty and wide-gabled; it endured the surges of battle, of hostile fire. The time was not yet come when the feud between son-in-law and father-in-law was fated to flare out after deadly hostility.

Then the mighty spirit who dwelt in darkness angrily endured the torment of hearing each day high revel in the hall. There was the sound of the harp, the clear song of the minstrel. He who could tell of men’s beginning from olden times spoke of how the Almighty wrought the world, the earth bright in its beauty which the water encompasses; the Victorious One established the brightness of sun and moon for a light to dwellers in the land, and adorned the face of the earth with branches and leaves; He also created life of all kinds which move and live. Thus the noble warriors lived in pleasure and plenty, until a fiend in hell began to contrive malice. The grim spirit was called Grendel, a famous march-stepper, who held the moors, the fen and the fastness. The hapless creature sojourned for a space in the sea-monsters’ home after the Creator had condemned him. The eternal Lord avenged the murder on the race of Cain, because he slew Abel. He did not rejoice in that feud. He, the Lord, drove him far from mankind for that crime. Thence sprang all evil spawn, ogres and elves and sea-monsters, giants too, who struggled long time against God. He paid them requital for that.

III

He went then when night fell to visit the high house, to see how the Ring-Danes had disposed themselves in it after the beer-banquet. Then he found therein the band of chieftains slumbering after the feast; they knew not sorrow, the misery of men, aught of misfortune. Straightway he was ready, grim and ravenous, savage and raging; and seized thirty thanes on their couches. Thence he departed homewards again, exulting in booty, to find out his dwelling with his fill of slaughter.

Then at dawn with the breaking of day the war-might of Grendel was made manifest to men; then after the feasting arose lamentation, a loud cry in the morning. The renowned ruler, the prince long famous, sat empty of joy; strong in might, he suffered, sorrowed for his men when they saw the track of the hateful monster, the evil spirit. That struggle was too hard, too hateful, and lasting. After no longer lapse than one night again he wrought still more murders, violence and malice, and mourned not for it; he was too bent on that. Then that man was easy to find who sought elsewhere for himself a more remote resting-place, a bed after the banquet, when the hate of the hall-visitant was shown to him, truly declared by a plain token; after that he kept himself further off, and more securely. He escaped the fiend.

Thus one against all prevailed and pitted himself against right until the peerless house stood unpeopled. That was a weary while. For the space of twelve winters the friend of the Scyldings bitterly suffered every woe, deep sorrows; wherefore it came to be known to people, to the children of men, sadly in songs, that Grendel waged long war with Hrothgar; many years he bore bitter hatred, violence and malice, an unflagging feud; peace he would not have with any man of Danish race, nor lay aside murderous death, nor consent to be bought off. Nor did any of the councillors make bold to expect fairer conditions from the hands of the slayer; but the monster, the deadly creature, was hostile to warriors young and old; he plotted and planned. Many nights he held the misty moors. Men do not know whither the demons go in their wanderings.

Thus the foe of men, the dread lone visitant, oftentimes wrought many works of malice, sore injuries; in the dark nights he dwelt in Heorot, the treasure-decked hall. He might not approach the throne, the precious thing, for fear of the Lord, nor did he know his purpose.

That was heavy sorrow, misery of mind for the friend of the Scyldings. Many a mighty one sat often in council; they held debate what was best for bold-minded men to do against sudden terrors. Sometimes in their temples they vowed sacrifices, they petitioned with prayers that the slayer of souls should succour them for the people’s distress. Such was their wont, the hope of the heathen. Their thoughts turned to hell; they knew not the Lord, the Judge of deeds; they wist not the Lord God; nor in truth could they praise the Protector of the heavens, the Ruler of glory. Woe is it for him who must needs send forth his soul in unholiness and fear into the embrace of the fire, hope for no solace, suffer no change! Well is it for him who may after the day of death seek the Lord, and crave shelter in the Father’s embrace!

IV

Thus the son of Healfdene was ever troubled with care; nor could the sage hero sweep aside his sorrows. That struggle was too hard, too hateful and lasting, which fell on the people—fierce hostile oppression, greatest of night-woes.

Hygelac’s thane, a valiant man among the Geats, heard of that at home, of the deeds of Grendel. He was the greatest in might among men at that time, noble and powerful. He bade a good ship to be built for him; he said that he was set on seeking the warlike king, the famous prince over the swan-road, since he had need of men. No whit did wise men blame him for the venture, though he was dear to them; they urged on the staunch-minded man, they watched the omens. The valiant man had chosen warriors of the men of the Geats, the boldest he could find; with fourteen others he sought the ship. A man cunning in knowledge of the sea led them to the shore.

Time passed on; the ship was on the waves, the boat beneath the cliff. The warriors eagerly embarked. The currents turned the sea against the sand. Men bore bright ornaments, splendid war-trappings, to the bosom of the ship. The men, the heroes on their willing venture, shoved out the well-timbered ship. The foamy-necked floater like a bird went then over the wave-filled sea, sped by the wind, till after due time on the next day the boat with twisted prow had gone so far that the voyagers saw land, the sea-cliffs shining, the steep headlands, the broad sea-capes. Then the sea was traversed, the journey at an end. The men of the Weders mounted thence quickly to the land; they made fast the ship. The armour rattled, the garments of battle. They thanked God that the sea voyage had been easy for them.

Then the watchman of the Scyldings whose duty it was to guard the sea-cliffs saw from the height bright shields and battle-equipment ready for use borne over the gangway. A desire to know who the men were pressed on his thoughts. The thane of Hrothgar went to the shore riding his steed; mightily he brandished his spear in his hands, spoke forth a question: “What warriors are ye, clad in corslets, who have come thus bringing the high ship over the way of waters, hither over the floods? Lo! for a time I have been guardian of our coasts, I have kept watch by the sea lest any enemies should make ravage with their sea-raiders on the land of the Danes. No shield-bearing warriors have ventured here more openly; nor do ye know at all that ye have the permission of warriors, the consent of kinsmen. I never saw in the world a greater earl than one of your band is, a hero in his harness. He is no mere retainer decked out with weapons, unless his face belies him, his excellent front. Now I must know your race rather than ye should go further hence and be thought spies in the land of the Danes. Now, ye far-dwellers, travellers of the sea, hearken to my frank thought. It is best to tell forth quickly whence ye are come.”

V

The eldest answered him; the leader of the troop unlocked his word-hoard: “We are men of the race of the Geats and hearth-companions of Hygelac. My father was famed among the peoples, a noble high prince called Ecgtheow; he sojourned many winters ere he passed away, the old man from his dwelling. Far and wide throughout the earth every wise man remembers him well. We have come with gracious intent to seek out thy lord, the son of Healfdene, the protector of his people. Be kindly to us in counsel. We have a great errand to the famous prince of the Danes. Nor shall anything be hidden there, I hope. Thou knowest if the truth is, as indeed we heard tell, that some sort of foe, a secret pursuer, works on the dark nights evil hatred, injury and slaughter, spreading terror. I can give Hrothgar counsel from a generous mind, how he may overcome the enemy wisely and well, if for him the torment of ills should ever cease, relief come again, and the surges of care grow cooler; or if he shall ever after suffer a time of misery and pain while the best of houses stands there in its lofty station.”

The watchman spoke, the fearless servant, where he sat his steed—a bold shield-warrior who ponders well shall pass judgment on both words and deeds: “I hear that this is a troop friendly to the prince of the Scyldings. Go forth and bear weapons and trappings; I will guide you. Likewise I will bid my henchmen honourably guard your vessel against all enemies, your newly-tarred ship on the sand, until once more the boat with twisted prow shall bear the beloved man to the coast of the Weders; to such a valiant one it shall be vouchsafed to escape unscathed from the rush of battle.”

They went on their way then. The ship remained at rest; the broad-bosomed vessel was bound by a rope, fast at anchor. The boar-images shone over the cheek armour, decked with gold; gay with colour and hardened by fire they gave protection to the brave men. The warriors hastened, went up together, until they could see the well-built hall, splendid and gold-adorned. That was foremost of buildings under the heavens for men of the earth, in which the mighty one dwelt; the light shone over many lands.

The man bold in battle pointed out to them the abode of brave men, as it gleamed, so that they could go thither. One of the warriors turned his horse, then spoke a word: “It is time for me to go. The almighty Father guard you by his grace safe in your venture. I will to the sea to keep watch for a hostile horde.”

VI

The street was paved with stones of various colours, the road kept the warriors together. The war-corslet shone, firmly hand-locked, the gleaming iron rings sang in the armour as they came on their way in their trappings of war even to the hall. Weary from the sea, they set down their broad shields, their stout targes against the wall of the building; they sat down on the bench then. The corslets rang out, the warriors’ armour. The spears, the weapons of seamen, of ash wood grey at the tip, stood all together. The armed band was adorned with war-gear. Then a haughty hero asked the men of battle as to their lineage: “Whence bear ye plated shields, grey corslets and masking helmets, this pile of spears? I am Hrothgar’s messenger and herald. I have not seen so many men of strange race more brave in bearing. I suppose ye have sought Hrothgar from pride, by no means as exiles but with high minds.”

The bold man, proud prince of the Weders, answered him, spoke a word in reply, stern under his helmet: “We are Hygelac’s table-companions; Beowulf is my name. I wish to tell my errand to the son of Healfdene, the famous prince, thy lord, if he will grant that we may greet him who is so gracious.” Wulfgar spoke—he was a man of the Wendels; his courage, his bravery and his wisdom had been made known to many: “I will ask the friend of the Danes, the prince of the Scyldings, the giver of rings, the renowned ruler, about thy venture as thou desirest, and speedily make known to thee the answer which the gracious one thinks fit to give me.” He turned quickly then to where Hrothgar sat, aged and grey-haired, amid the band of earls; the bold man went till he stood before the shoulders of the Danish prince; he knew courtly custom. Wulfgar spoke to his gracious master: “Men of the Geats, come from afar, have been brought here over the stretch of the ocean. The warriors call the eldest one Beowulf. They request, my lord, that they may exchange words with thee. Refuse them not thy answer, gracious Hrothgar. They seem in their war-gear worthy of respect from the noble-born. Of a truth the leader is valiant who guided the heroes hither.”

VII

Hrothgar spoke, the protector of the Scyldings: “I knew him when he was a youth. His aged father was called Ecgtheow; to him Hrethel of the Geats gave his only daughter in marriage. His son has now come here boldly, has sought a gracious friend. Then seafaring men, who brought precious gifts of the Geats hither as a present, said that he, mighty in battle, had the strength of thirty men in the grip of his hand. May Holy God in his graciousness send him to us, to the West-Danes, as I hope, against the terror of Grendel. I shall offer treasures to the valiant one for his courage. Do thou hasten, bid them enter to see the friendly band all together; tell them also with words that they are welcome to the people of the Danes.” Then Wulfgar went toward the door of the hall, spoke a word in the doorway: “My victorious lord, prince of the East-Danes, bade me tell you that he knows your lineage, and that ye, bold in mind, are welcome hither over the sea-surges. Now ye may go in your war-gear under battle-helmets to see Hrothgar; let your battle-shields, spears, deadly shafts, await here the issue of the speaking.”

The mighty one rose then, around him many a warrior, excellent troop of thanes. Some waited there, kept watch over their trappings, as the bold man bade them. They hastened together, as the warrior guided, under the roof of Heorot; the man, resolute in mind, stern under his helmet, went till he stood within the hall. Beowulf spoke—on him his corslet shone, the shirt of mail sewn by the art of the smith: “Hail to thee, Hrothgar; I am Hygelac’s kinsman and thane. I have in my youth undertaken many heroic deeds. The ravages of Grendel were made known to me in my native land. Seafarers say that this hall, the noblest building, stands unpeopled and profitless to all warriors, after the light of evening is hidden under cover of heaven. Then my people counselled me, the best of men in their wisdom, that I should seek thee, Prince Hrothgar, because they knew the power of my strength, they saw it themselves, when I came out of battles, blood-stained from my foes, where I bound five, ruined the race of the monsters and slew by night the sea-beasts mid the waves, suffered sore need, avenged the wrong of the Weders, killed the foes—they embarked on an unlucky venture. And now alone I shall achieve the exploit against Grendel, the monster, the giant. I wish now at this time to ask thee one boon, prince of the Bright-Danes, protector of the Scyldings: that thou, defence of warriors, friendly prince of the people, wilt not refuse me, now I have come thus far, that I and my band of earls’, this bold troop, may cleanse Heorot unaided. I have also heard that the monster in his madness cares naught for weapons; wherefore I scorn to bear sword or broad shield, yellow targe to the battle, so may Hygelac my lord be gracious in mind to me; but with my grip I shall seize the fiend and strive for his life, foe against foe. There he whom death takes must needs trust to the judging of the Lord. I think that he is minded, if he can bring it to pass, to devour fearlessly in the battle-hall the people of the Geats, the flower of men, as he often has done. Not at all dost thou need to protect my head, but if death takes me he will have me drenched in blood; he will carry off the bloody corpse, will think to hide it; the lone-goer will feed without mourning, he will stain the moor-refuges. No longer needst thou care about the sustenance of my body. Send to Hygelac, if battle takes me off, the best of battle-garments that arms my breast, the finest of corslets. That is a heritage from Hrethel, the work of Weland. Fate ever goes as it must.”

Hrothgar spoke, the protector of the Scyldings: “Thou hast sought us, my friend Beowulf, for battle and from graciousness. Thy father achieved the greatest of feuds; he became the slayer of Heatholaf among the Wulfings; then the race of the Weders would not receive him because of threatening war. Thence he sought the people of the South-Danes, the honourable Scyldings, over the surging of the waves. Then I had just begun to rule the Danish people and in youth held a wide-stretched kingdom, a stronghold of heroes. Then Heregar was dead, my elder kinsman, the son of Healfdene had ceased to live; he was better than I. Afterwards I ended the feud with money; I sent old treasures to the Wulfings over the back of the water; he swore oaths to me. It is sorrow for me in my mind to tell any man what malice and sudden onslaughts Grendel has wrought on Heorot with his hostile thoughts. Thinned is my troop in hall, my war-band. Fate has swept them away to the dread Grendel. God may easily part the bold enemy from his deeds.

“Full often did warriors drunken with beer boast over the ale-cup that they would await Grendel’s attack with dread blades in the beer-hall. Then in the morning, when day dawned, this mead-hall, the troop-hall, was stained with blood; all the ale-benches drenched with gore, the hall with blood shed in battle. I had so many the less trusty men, dear veterans, since death had carried off these. Sit down now at the banquet, and speak thy mind, tell the men of victorious fame, as thy mind prompts.”

Then a bench was cleared in the beer-hall for the men of the Geats together; there the bold-minded ones went and sat down, exceeding proud. A thane who bore in his hands the decked ale-cup performed the office, poured out the gleaming beer. At times the minstrel sang clearly in Heorot; there was joy of heroes, a great band of warriors, Danes and Weders.

IX

Unferth spoke, son of Ecglaf, who sat at the feet of the prince of the Scyldings. He began dispute—the journey of Beowulf, the brave seafarer, was a great bitterness to him, because he did not grant that any other man in the world accomplished greater exploits under heaven than he himself: “Art thou that Beowulf who strove with Breca, contended on the wide sea for the prize in swimming, where ye two tried the floods in your pride, and risked your lives in the deep water from presumption? Nor could any man, friend or foe, prevent the sorrowful journey; then ye two swam on the sea, where ye plied the ocean-streams with your arms, measured the sea-paths, threw aside the sea with your hands, glided over the surge; the deep raged with its waves, with its wintry flood. Seven nights ye toiled in the power of the water; he outstripped thee in swimming, had greater strength. Then in the morning the sea bore him to the land of the Heathoremes. Thence, dear to his people, he sought his loved country, the land of the Brondings, the fair stronghold, where he ruled over people, castle and rings. The son of Beanstan in truth fulfilled all his pledge to thee. Wherefore I expect a worse fate for thee, though everywhere thou hast withstood battle-rushes, grim war, if thou durst await Grendel throughout the night near at hand.”

Beowulf spoke, son of Ecgtheow: “Lo! thou hast spoken a great deal, friend Unferth, about Breca, drunken as thou art with beer; thou hast told of his journey. I count it as truth that I had greater might in the sea, hardships mid the waves, than any other man.

“We arranged that and made bold, while we were youths—we were both then still in our boyhood—that we two should risk our lives out on the sea; and thus we accomplished that. We held naked swords boldly in our hands when we swam in the ocean; we thought to protect ourselves against the whales. In no wise could he swim far from me on the waves of the flood, more quickly on the sea; I would not consent to leave him. Then we were together on the sea for the space of five nights till the flood forced us apart, the surging sea, coldest of storms, darkening night, and a wind from the north, battle-grim, came against us. Wild were the waves; the temper of the sea-monsters was stirred. There did my shirt of mail hard-locked by hand stand me in good stead against foes; the woven battle-garment, adorned with gold, lay on my breast. A spotted deadly foe drew me to the depths, had me firmly and fiercely in his grip; yet it was granted to me that I pierced the monster with my point, my battle-spear. The rush of battle carried off the mighty sea-monster by my hand.

X

“Thus oftentimes malicious foes pressed me hard. I served them with my good sword, as was fitting. They had not joy of their feasting, the evildoers, from devouring me, from sitting round the banquet near the bottom of the sea; but in the morning they lay cast up on the shore, wounded with swords, laid low by blades, so that no longer they hindered seafarers on their voyage over the high flood. Light came from the east, bright beacon of God. The surges sank down, so that I could behold the sea-capes, the windy headlands. Fate often succours the undoomed warrior when his valour is strong.

“Yet it was my fortune to slay with the sword nine sea-monsters. I have not heard under the arching sky of heaven of harder fighting by night, nor of a more hapless man in the streams of ocean. Yet I escaped with my life from the grasp of foes, weary of travel. Then the sea, the flood, the raging surges bore me to the shore in the land of the Finns.

“I have not heard such exploits told of thee, dread deeds, terror of swords; never yet did Breca or either of you two in the play of battle perform so bold a deed with gleaming blades—I do not boast of the struggle—though thou earnest to be the murderer of thy brother, thy near kinsman. For that thou must needs suffer damnation in hell, though thy wit is strong. Forsooth, I tell thee, son of Ecglaf, that Grendel, the fearful monster, had never achieved so many dread deeds against thy prince, malice on Heorot, if thy thoughts and mind had been as daring as thou thyself sayest. But he has found out that he need not sorely dread the feud, the terrible sword-battle of your people, the victorious Scyldings; he takes pledges by force, he spares none of the Danish people, but he lives in pleasure, sleeps and feasts; he looks for no fight from the Spear-Danes. But soon now I shall show him battle, the might and courage of the Geats. He who may will go afterwards, brave to the mead, when the morning light of another day, the sun clothed with sky-like brightness, shines from the south over the children of men.”

Then glad was the giver of treasure, grey-haired and famed in battle; the prince of the Bright-Danes trusted in aid; the protector of the people heard in Beowulf a resolute purpose. There was laughter of heroes; talk was heard; words were winsome.

Wealtheow went forth, Hrothgar’s queen, mindful of what was fitting; gold-adorned, she greeted the warriors in hall; and the freeborn woman first offered the goblet to the guardian of the East-Danes; bade him be of good cheer at the beer-banquet, be dear to his people. He gladly took part in the banquet and received the hall-goblet, the king mighty in victory. Then the woman of the Helmings went about everywhere among old and young warriors, proffered the precious cup, till the time came that she, the ring-decked queen, excellent in mind, bore the mead-flagon to Beowulf. She greeted the prince of the Geats, thanked God with words of sober wisdom that her wish had been fulfilled, that she might trust to some earl as a comfort in trouble. He, the warrior fierce in fight, took that goblet from Wealtheow, and then, ready for battle, uttered speech.

Beowulf spoke, son of Ecgtheow: “That was my purpose when I launched on the ocean, embarked on the sea-boat with the band of my warriors, that I should work the will of your people to the full, or fall a corpse fast in the foe’s grip. I shall accomplish deeds of heroic might, or endure my last day in the mead-hall.”

Those words, the boasting speech of the Geat, pleased the woman well. Decked with gold, the free-born queen of the people went to sit by her prince. Then again as before there was excellent converse in hall, the warriors in happiness, the sound of victorious people, till all at once Healfdene’s son was minded to seek his evening’s rest. He knew that war was destined to the high hall by the monster after they could no longer see the light of the sun, and when, night growing dark over all, the shadowy creatures came stalking, black beneath the clouds. The troop all rose.

Then one warrior greeted the other, Hrothgar Beowulf, and wished him success, power over the wine-hall, and spoke these words: “Never before did I trust to any man, since I was able to lift hand and shield, the excellent hall of the Danes, except to thee now. Have now and hold the best of houses. Be mindful of fame, show a mighty courage, watch against foes. Nor shalt thou lack what thou desirest, if with thy life thou comest out from that heroic task.”

XI

Then Hrothgar went his way with his band of heroes, the protector of Scyldings out of the hall; the warlike king was minded to seek Wealtheow the queen for his bedfellow. The glorious king had, as men learned, set a hall-guardian against Grendel; he performed a special service for the prince of the Danes, kept watch against monsters. Truly the prince of the Geats relied firmly on his fearless might, and the grace of the Lord. Then he laid aside his iron corslet, the helmet from his head, gave his ornamented sword, best of blades, to his servant and bade him keep his war-gear.

Then the valiant one, Beowulf of the Geats, spoke some words of boasting ere he lay down on his bed: “I do not count myself less in war-strength, in battle-deeds, than Grendel does himself; wherefore I will not slay him, spoil him of life by sword, although I might. He knows not the use of weapons so as to strike at me, hew my shield, though he may be mighty in works of malice; but we two shall do without swords in the night, if he dare to seek war without weapons, and afterwards the wise God, the holy Lord, shall award fame to whatever side seems good to Him.” The bold warrior lay down, the earl’s face touched the bolster; and round him many a mighty sea-hero bent to his couch in the hall. None of them thought that he should go thence and seek again the loved land, the people or stronghold where he was fostered; but they had heard that murderous death had ere now carried off far too many of Danish people in the wine-hall. But the Lord gave them success in war, support and succour to the men of the Weders, so that through the strength of one, his own might, they all overcame their foe. The truth has been made known, that mighty God has ever ruled over mankind.

The shadowy visitant came stalking in the dark night. The warriors slept, who were to keep the antlered building, all save one. That was known to men that the ghostly enemy might not sweep them off among the shadows, for the Lord willed it not; but he, watching in anger against foes, awaited in wrathful mood the issue of the battle.

XII

Then from the moor under the misty cliffs came Grendel, he bore God’s anger. The foul foe purposed to trap with cunning one of the men in the high hall; he went under the clouds till he might see most clearly the wine-building, the gold-hall of warriors, gleaming with plates of gold. That was not the first time he had sought Hrothgar’s home; never in his life-days before or since did he find bolder heroes and hall-thanes. The creature came, bereft of joys, making his way to the building. Straightway the door, firm clasped by fire-hardened fetters, opened, when he touched it with his hands; then, pondering evil, he tore open the entry of the hall when he was enraged. Quickly after that the fiend trod the gleaming floor, moved angry in mood. A baleful light like flame flared from his eyes. He saw in the building many heroes, the troop of kinsmen sleeping together, the band of young warriors. Then his mind exulted. The dread monster purposed ere day came to part the life of each one from the body, for the hope of a great feasting filled him. No longer did fate will that after that night he might seize more of mankind. The kinsman of Hygelac, exceeding strong, beheld how the foul foe was minded to act with his sudden grips.

Nor did the monster think to delay, but first he quickly seized a sleeping warrior; suddenly tore him asunder, devoured his body, drank the blood from his veins, swallowed him with large bites. Straightway he had consumed all the body, even the feet and hands. He stepped forward nearer, laid hold with his hands of the resolute warrior on his couch; the fiend stretched his hand towards him. Beowulf met the attack quickly and propped himself on his arm. Forthwith the upholder of crime found that he had not met in the world, on the face of the earth among other men, a mightier hand-grip. Fear grew in his mind and heart; yet in spite of that he could not make off. He sought to move out; he was minded to flee to his refuge, to seek the troop of devils. His task there was not such as he had found in former days.

Then the brave kinsman of Hygelac remembered his speech in the evening; he stood upright and seized him firmly. The fingers burst, the monster was moving out; the earl stepped forward. The famous one purposed to flee further, if only he might, and win away thence to the fen-strongholds; he knew the might of his fingers was in the grip of his foe. That was an ill journey when the ravager came to Heorot. The warriors’ hall resounded. Terror fell on all the Danes, on the castle-dwellers, on each of the bold men, on the earls. Wroth were they both, angry contestants for the house. The building rang aloud.

Then was it great wonder that the wine-hall withstood the bold fighters; that it fell not to the ground, the fair earth-dwelling; but it was too firmly braced within and without with iron bands of skilled workmanship. There many a mead-bench decked with gold bent away from the post, as I have heard, where the foemen fought. The wise men of the Scyldings looked not for that before, that any man could ever shatter it, rend it with malice in any way, excellent and bone-adorned as it was, unless the embrace of fire could swallow it in smoke. A sound arose, passing strange. Dread fear came upon each of the North-Danes who heard the cry from the wall, the lament of God’s foe rise, the song of defeat; the hell-bound creature, crying out in his pain. He who was strongest in might among men at that time held him too closely.

The protector of earls was minded in no wise to release the deadly visitant alive, nor did he count his life as useful to any man.

There most eagerly this one and that of Beowulf’s men brandished old swords, wished to save their leader’s life, the famous prince, if only they could. They did not know, when they were in the midst of the struggle, the stern warriors, and wished to strike on all sides, how to seek Grendel’s life. No choicest of swords on the earth, no war-spear, would pierce the evil monster; but Beowulf had given up victorious weapons, all swords. His parting from life at that time was doomed to be wretched, and the alien spirit was to travel far into the power of the fiends.

Then he who before in the joy of his heart had wrought much malice on mankind—he was hostile to God—found that his body would not follow him, for the brave kinsman of Hygelac held him by the hand. Each was hateful to the other while he lived. The foul monster suffered pain in his body. A great wound was seen in his shoulder, the sinews sprang apart, the body burst open. Fame in war was granted to Beowulf. Grendel must needs flee thence under the fen-cliffs mortally wounded, seek out his joyless dwelling. He knew but too well the end of his life was come, the full count of his days. The desire of all the Danes was fulfilled after the storm of battle.

Then he who erstwhile came from afar, shrewd and staunch, had cleansed the hall of Hrothgar, freed it from battle. He rejoiced in the night-work, in heroic deeds. The prince of the Geat warriors had fulfilled his boast to the East-Danes; likewise he cured all their sorrows, sufferings from malicious foes, which they endured before and were forced to bear in distress, no slight wrong. That was a clear token when the bold warrior laid down the hand, the arm and shoulder under the wide roof—it was all there together—the claw of Grendel.

XIV

Then in the morning, as I have heard, around the gift-hall was many a warrior; leaders came from far and near throughout the wide ways to behold the wonder, the tracks of the monster. His going from life did not seem grievous to any man who saw the course of the inglorious one, how, weary in mind, beaten in battle, fated and fugitive, he left behind him on his way thence to the mere of the monsters marks of his life-blood. Then the water was surging with blood, the foul welter of waves all mingled with hot gore; it boiled with the blood of battle. The death-doomed one dived in, then bereft of joy in his fen-refuge he laid down his life, his heathen soul, when hell received him. Thence again old comrades went, also many a young man, in merry companionship, the brave men riding on horses from the mere, warriors on bay steeds. There Beowulf’s fame was proclaimed. Oftentimes many a one said that neither south nor north between the seas, over the wide earth, under the vault of the sky, was there any better among warriors, more worthy of a kingdom. Nor in truth did they blame their friendly lord, gracious Hrothgar, for that was a good king.

At times the men doughty in battle let their sorrel horses run, race against one another, where the land-ways seemed fair to them, known for their good qualities; at times the king’s thane, a man with many tales of exploits, mindful of measures, he who remembered a great number of the old legends, made a new story of things that were true. The man began again wisely to frame Beowulf’s exploit and skilfully to make deft measures, to deal in words. He spoke all that he had heard told of Sigemund’s mighty deeds, much that was unknown, the warfare of the son of Wæls, the far journeys, the hostility and malice of which the children of men knew not at all, except Fitela who was with him when he was minded to say somewhat of such things, the uncle to his nephew; for they were always in every struggle bound together by kinship. They had felled with their swords very many of the race of giants. There sprang up for Sigemund after his death no little fame when the man bold in battle killed the dragon, the guardian of the treasure. Under the grey stone he ventured alone, the son of a chieftain, on the daring deed; Fitela was not with him. Yet it was granted to him that that sword pierced the monstrous dragon, so that it stood in the wall, the noble blade. The dragon died violently. The hero had brought it to pass by his valour that he could use the ring-hoard as he chose. The son of Wæls loaded the sea-boat, bore to the ship’s bosom the bright ornaments. The dragon melted in heat.

He was by far the most famous of adventurers among men, protector of warriors by mighty deeds; he prospered by that earlier, when the boldness, the strength and the courage of Heremod lessened. He was betrayed among the Eotens into the power of his enemies, quickly driven out. Surges of sorrow pressed him too long; he became a deadly grief to his people, to all his chieftains. So also many a wise man who trusted to him as a remedy for evils lamented in former times the valiant one’s journey, that the prince’s son was destined to prosper, inherit his father’s rank, rule over the people, the treasure and the prince’s fortress, the kingdom of heroes, the land of the Scyldings. There did he, the kinsman of Hygelac, become dearer to all men and to his friends than he. Treachery came upon him.

At times in rivalry they measured the yellow streets with their horses. Then the light of morning had quickly mounted up. Many a retainer went bold-minded to the high hall to behold the rare wonder; the king himself also, the keeper of ring-treasures, came glorious from his wife’s chamber, famed for his virtues, with a great troop, and his queen with him measured the path to the mead-hall with a band of maidens.

XV

Hrothgar spoke—he went to the hall, stood on the doorstep, looked on the lofty gold-plated roof and Grendel’s hand—“For this sight thanks be straightway rendered to the Almighty. I suffered much that was hateful, sorrows at the hands of Grendel; ever may God, the glorious Protector, perform wonder after wonder.

“That was not long since when I looked not ever to find solace for any of my woes, when the best of houses stood blood-stained, gory from battle; woe wide-spread among all councillors who had no hope of ever protecting the fortress of warriors against foes, against demons and evil spirits. Now the warrior has performed the deed through the Lords might which formerly all of us could not contrive with our cunning. Lo! a woman who has borne such a son among the peoples, if she yet lives, may say that the ancient Lord was gracious to her in the birth of her son. Now I will love thee in my heart as my son, Beowulf, best of men; keep well the new kinship. Thou shalt lack none of the things thou desirest in the world, which I can command. Full often have I for less cause bestowed reward on a slighter warrior, a weaker in combat, to honour him with treasures. Thou hast brought it to pass for thyself by deeds that thy glory shall live forever. The All-Ruler reward thee with good things as He has done till now.”

Beowulf spoke, son of Ecgtheow: “We accomplished that heroic deed, that battle, through great favour. We risked ourselves boldly against the might of the monster. I had rather that thou couldst have seen him, the fiend in his trappings, weary unto death. I thought to bind him speedily with strong clasps on his death-bed, so that he must needs lie in his death-agony by my hand-grip, unless his body should slip away. I could not, since the Lord willed it not, prevent his passing out. I did not hold him closely enough, the deadly enemy; the foe was too mighty in going. Nevertheless he left his hand, arm and shoulder, to serve as a token of his flight. Yet the wretched creature won no solace there; no longer lives the malicious foe pressed by sins, but pain has embraced him closely with hostile grasp, with ruinous bonds. There the creature stained with sin must needs await the great doom, what judgment the bright Lord will award him.”

Then the son of Ecglaf was a more silent man in boasting of war-deeds, when the chieftains beheld by the strength of the earl the hand, the fingers of the monster, stretching up to the high roof; each at its tip, each place where the nails were, was like steel, the heathen’s claw, the monstrous spike of the fighter. Everyone said that no well-tried sword of brave men would wound him, would shorten the monster’s bloody battle-fist.

XVI

Then it was quickly commanded that Heorot should be decked within with hands. There were many there, men and women, who made ready the wine-building, the guest-hall. Woven hangings gleamed, gold-adorned, on the walls, many wondrous sights for all men who look on such things. That bright building was all sorely shattered, though firm within with its iron clasps; its door-hinges burst. The roof alone survived all scatheless, when the monster stained with evil deeds turned in flight, despairing of life. That is not easy to avoid—let him do it who will—but he must needs seek the place forced on him by necessity, prepared for all who bear souls, for the children of men, for the dwellers on earth, where his body sleeps after the banquet fast in its narrow bed.

Then was the time convenient and fitting that Healfdene’s son should go to the hall; the king himself wished to join in the banquet. I have not heard of a people who showed a nobler bearing with a greater troop about their giver of treasure. The famous ones then sat down on the bench, rejoiced in the feast; in seemly fashion they took many a mead-goblet; brave-minded kinsmen were in the high hall, Hrothgar and Hrothulf. Heorot within was filled with friends. Not yet at this time had the Scyldings practised treachery.

The son of Healfdene gave then to Beowulf a golden ensign as a reward for victory, an ornamented banner with a handle, a helmet and corslet, a famous precious sword. Many saw them borne before the warrior. Beowulf took the goblet in hall; he needed not to be ashamed in front of the warriors of the bestowing of gifts.

I have not heard of many men giving to others on the ale-bench in more friendly fashion four treasures decked with gold. Around the top of the helmet a jutting ridge twisted with wires held guard over the head, so that many an old sword, proved hard in battle, could not injure the bold man, when the shield-bearing warrior was destined to go against foes. Then the protector of earls commanded eight horses with gold-plated bridles to be led into the hall, into the house; on one of them lay a saddle artfully adorned with gold, decked with costly ornament. That was the war-seat of the noble king, when the son of Healfdene was minded to practise sword-play. Never did the bravery of the far-famed man fail in the van when corpses were falling. Then the protector of the friends of Ing gave power over both to Beowulf, over horses and weapons; he bade him use them well. Thus manfully did the famous prince, the treasure-keeper of heroes, reward the rushes of battle with steeds and rich stores, so that he who wishes to speak truth in seemly fashion will never scoff at them.

XVII

Further the lord of earls bestowed treasure on the mead-bench, ancient blades, to each of those who travelled the ocean path with Beowulf; and he bade recompense to be made with gold for the one whom Grendel before murderously killed. So he was minded to do with more of them, if wise God and the man’s courage had not turned aside such a fate from them. The Lord ruled over all mankind as He still does. Wherefore understanding, forethought of soul, is everywhere best. He who sojourns long in the world in these days of sorrow must needs suffer much of weal and woe.

There was song and music mingled before Healfdene’s chieftain; the harp was touched; a measure often recited at such times as it fell to Hrothgar’s minstrel to proclaim joy in hall along the mead-bench. Hnæf of the Scyldings, a hero of the Half-Danes, was fated to fall in the Frisian battle-field when the sudden onslaught came upon them, the sons of Finn. “Nor in truth had Hildeburh cause to praise the faith of the Eotens; sinless, she was spoiled of her dear ones at the shield-play, a son and a brother; wounded with the spear, they fell in succession. She was a sorrowing woman. Not without cause did the daughter of Hoc lament her fate, when morning came when she might see the slaughter of kinsmen under the sky. Where erstwhile he had had greatest joy in the world, war carried off all the thanes of Finn except a very few, so that in no wise could he offer fight to Hengest in the battle-field, nor protect by war the sad survivors from the prince’s thane; but they offered them conditions, that they would give up to them entirely another building, the hall and high seat; that they might have power over half of it with the men of the Eotens, and that the son of Folcwalda would honour the Danes each day with gifts at the bestowal of presents, would pay respect to Hengest’s troop with rings, just as much as he would encourage the race of the Frisians in the beer-hall with ornaments of plated gold. Then on both sides they had faith in firm-knit peace. Finn swore to Hengest deeply, inviolably with oaths, that he would treat the sad survivors honourably according to the judgment of the councillors, that no man there should break the bond by word or deed, nor should they ever mention it in malice, although they had followed the slayer of their giver of rings after they had lost their leader, since the necessity was laid upon them; if then any one of the Frisians should recall to mind by dangerous speech the deadly hostility, then it must needs recall also the edge of the sword.

“The oath was sworn and rich gold taken from the treasure. The best of the heroes of the warlike Scyldings was ready on the funeral fire. On that pyre the blood-stained shirt of mail was plain to see, the swine-image all gold, the boar hard as iron, many a chieftain slain with wounds. Many had fallen in the fight. Then Hildeburh bade her own son to be given over to the flames at Hnæf’s pyre, his body to be burned and placed on the funeral fire. The woman wept, sorrowing by his side; she lamented in measures. The warrior mounted up. The greatest of funeral fires wound up to the clouds, it roared in front of the mound. Heads melted, wounds burst open, while blood gushed forth from the gashes in the bodies. The fire, greediest of spirits, consumed all those of both peoples whom war carried off there. Their mightiest men had departed.

“The warriors went then, bereft of friends, to visit the dwellings, to see the land of the Frisians, the homes and the stronghold. Then Hengest dwelt yet in peace with Finn for a winter stained with the blood of the slain; he thought of his land though he could not drive the ring-prowed ship on the sea (the ocean surged with storm, rose up against the wind; winter bound the waves with fetters of ice), till another year came into the dwellings; as those still do now who ever await an opportunity, the bright clear weather. Then winter was past; the bosom of the earth was fair; the exile purposed to depart, the guest out of the castle; he thought rather of vengeance for sorrow than of the sea journey, if he could bring the battle to pass in which he thought to take vengeance on the children of the Eotens. So he let things take their course when Hunlafing laid in his bosom the gleaming sword, best of blades. Its edges were famed among the Eotens. Even so did deadly death by the sword come upon brave Finn in his own home, when Guthlaf and Oslaf after their sea journey sorrowfully lamented the grim attack; they were wroth at their manifold woes; their restless spirit could not be ruled in their breast. Then was the hall reddened with corpses of foes, Finn slain likewise, the king mid his troop, and the queen taken. The warriors of the Scyldings bore to the ships all the house-treasure of the king of the land, whatever they could find at Finn’s home of ornaments and jewels. They bore away on the sea voyage the noble woman to the Danes, led her to her people.”

The song was sung, the glee-man’s measure. Joy rose again, bench-music rang out clear, servants gave out wine from wondrous goblets. Then Wealtheow, under her golden circlet, came forth where the two valiant ones were sitting, uncle and nephew. At that time there was peace yet between them, each true to the other. Likewise Unferth sat there as a squire at the feet of the prince of the Scyldings. Each of them trusted his heart, that he had a noble mind, though he had not been faithful to his kinsmen at the play of swords. Then spoke the queen of the Scyldings: “Receive this goblet, my prince, giver of treasure. Rejoice, gold-friend of warriors, and speak to the Geats with kindly words, as it is fitting to do. Be gracious to the Geats, mindful of gifts; far and near now thou hast peace. They said that thou wast minded to take the warrior for son. Heorot is cleansed, the bright ring-hall; be generous with many rewards while thou mayst, and leave to thy kinsmen subjects and kingdom, when thou must needs go forth to face thy destiny. I know my gracious Hrothulf, that he will treat the young men honourably, if thou, friend of the Scyldings, pass from the world before him. I think that he will richly reward our children, if he forgets not all the favours we formerly showed him for his pleasure and honour, while he was still a child.”

She turned then towards the bench where her sons were, Hrethric and Hrothmund, and the sons of heroes, the young men together; there the valiant one, Beowulf of the Geats, sat by the two brothers.

XIX

To him was the flagon borne and a friendly invitation offered with words and the twisted gold vessel graciously presented; two bracelets, a corslet and rings, greatest of necklaces, of those which I have heard of on earth.

I have not heard of a better treasure-hoard of heroes under the sky since Hama carried off to the gleaming castle the necklace of the Brosings, the trinket and treasure; he fled the malicious hostility of Eormenric; he chose everlasting gain. Hygelac of the Geats, grandson of Swerting, had the ring on his last expedition, when beneath his banner he defended the treasure, guarded the booty of battle. Fate took him off, when in his pride he suffered misfortune in fight against the Frisians; the mighty prince bore the ornament, the precious stones over the sea; he fell under his shield. Then the king’s body passed into the power of the Franks, his breast-garments and the ring also; less noble warriors stripped the bodies of the men of the Geats after the carnage of war; their bodies covered the battle-field. The hall rang with shouts of approval.

Wealtheow spoke, she uttered words before the troop: “Enjoy this ring happily, dear young Beowulf; and use this corslet, the great treasures, and prosper exceedingly; make thyself known mightily, and be to these youths kindly in counsel. I will not forget thy reward for that. Thou hast brought it about that far and near men ever praise thee, even as far as the sea hems in the home of the winds, the headlands. Blessed be thou while thou livest, nobly-born man. I will grant thee many treasures. Be thou gracious in deeds to my son, thou who art now in happiness. Here each earl is true to the other, gentle in mind, loyal to the lord. The thanes are willing, the people all ready, noble warriors after drinking. Do as I bid.”

She went then to the seat. There was the choicest of banquets; the men drank wine; they knew not fate, dread destiny, as it had been dealt out to many of the earls. Afterwards came evening, and Hrothgar went to his chamber, the mighty one to his couch. A great band of earls occupied the hall, as they often did before; they cleared away bench-boards; it was spread over with beds and bolsters. One of the revellers, ready and fated, sank to his couch in the hall. At their heads they placed the war-shields, the bright bucklers. There on the bench was plainly seen above the chieftains the helmet rising high in battle, the ringed corslet, the mighty spear. It was their custom that often both at home and in the field they should be ready for war, and equally in both positions at all such times as distress came upon their lord. Those people were good.

XX

They sank then to sleep. One sorely paid for his evening rest, as had full often come to pass for them, when Grendel held the gold-hall, and did wickedness until the end came, death after sins. That was seen, widely known among men, that an avenger, Grendel’s mother, a she-monster, yet survived the hateful one, a long while after the misery of war. She who was doomed to dwell in the dread water, the cold streams, after Cain killed his only brother, his father’s son, forgot not her misery. He departed then fated, marked with murder, to flee from the joys of men; he dwelt in the wilderness. Thence sprang many fated spirits; Grendel was one of them, a hateful fierce monster; he found at Heorot a man keeping watch, waiting for war. There the monster came to grips with him; yet he remembered the power of his strength, the precious gift which God gave him, and he trusted for support, for succour and help, to Him who rules over all. By that he overcame the fiend, laid low the spirit of hell. Then he departed, the foe of mankind, in misery, reft of joy, to seek his death-dwelling. And his mother then still purposed to go on the sorrowful journey, greedy and darkly-minded, to avenge her son’s death.

She came then to Heorot where the Ring-Danes slept throughout that hall. Then straightway the old fear fell on the earls, when Grendel’s mother forced her way in. The dread was less by just so much as the strength of women, the war-terror of a woman, is less than a man, when the bound sword shaped by the hammer, the blood-stained blade strong in its edges, cuts off the boar-image on the foeman’s helmet. Then in the hall was the strong blade drawn, the sword over the seats; many a broad buckler raised firmly in hand. He thought not of helmet nor of broad corslet, when the terror seized him.

She was in haste, was minded to go thence and save her life when she was discovered. Quickly she had seized one of the chieftains with firm grip; then she went to the fen. That was the dearest of heroes to Hrothgar among his followers between the seas, a mighty shield-warrior, whom she slew on his couch, a noble man of great fame. Beowulf was not there, but another lodging had been set apart for him earlier, after the giving of treasure to the famous Geat. There was clamour in Heorot. She had carried off the famous blood-stained hand. Care was created anew, brought to pass in the dwellings. That was no good bargain which they had to pay for in double measure with lives of friends. Then the wise king, the grey battle-warrior, was troubled in heart, when he knew that the noble thane was lifeless, that the dearest one was dead.

Beowulf was quickly brought to the castle, the victorious warrior. At dawn that earl, the noble hero himself with his comrades, went to where the wise man was waiting to see whether the All-Ruler would ever bring to pass a change after the time of woe. Then the man famous in fight went with his nearest followers along the floor—(the hall-wood resounded)—till he greeted the wise one with words, the prince of the friends of Ing; he asked if, as he hoped, he had had a peaceful night.

XXI

Hrothgar spoke, protector of the Scyldings: “Ask thou not after happiness. Sorrow is made anew for the Danish people. Æschere is dead, Yrmenlaf’s elder brother, my counsellor and my adviser, trusted friend, in such times as we fended our heads in war, when the foot-warriors crashed together and hewed the helms. Such should an earl be, a trusty chieftain, as Æschere was.

“That unjust slaughterous spirit slew him with her hands in Heorot. I know not whither the monster, made known by her feasting, journeyed back exulting in the corpse. She avenged the fight in which last night thou didst violently kill Grendel with hard grips because too long he lessened and slew my people. He fell in combat, guilty of murder, and now another mighty evil foe has come; she was minded to make requital for her son, and she has overmuch avenged the hostile deed, as it may seem to many a thane who grieves in mind for the giver of treasure with heavy heart-sorrow. Now low lies the hand which was ready for all your desires.

“I heard dwellers in the land, my people, counsellors in hall, say that they saw two such great march-steppers, alien spirits, hold the moors. One of them was, as far as they could certainly know, the likeness of a woman; the other wretched creature trod the paths of exile in man’s shape, except that he was greater than any other man. Him in days past the dwellers in the land named Grendel; his father they know not; nor whether there were born to him earlier any dark spirits.

“They possess unknown land, wolf-cliffs, windy crags, a dangerous fen-path, where the mountain stream falls down under the darkness of the rocks, a flood under the earth. That is not a mile hence where the mere stands; over it hang rime-covered groves; the wood firm-rooted overshadows the water. There each night a baleful wonder may be seen, a fire on the flood. There is none so wise of the children of men who knows those depths. Though the heath-stepper hard pressed by the hounds, the hart strong in antlers, should seek the forest after a long chase, rather does he yield up his life, his spirit on the shore, than hide his head there. That is an eerie place. Thence the surge of waves mounts up dark to the clouds, when the wind stirs up hostile storms till the air darkens, the skies weep.

“Now once more help must come from thee alone. Thou dost not yet know the lair, the dangerous place, where thou mayest find the sinful creature; seek if thou darest. If thou comest away alive, I will reward thee for that onslaught, as erstwhile I did, with treasures, old precious things, twisted gold.”

XXII

Beowulf spoke, son of Ecgtheow: “Sorrow not, wise warrior. It is better for each to avenge his friend than greatly to mourn. Each of us must needs await the end of life in the world; let him who can achieve fame ere death. That is best for a noble warrior when life is over. Rise up, guardian of the realm; let us go quickly hence to behold the track of Grendel’s kinswoman. I promise thee she shall not escape under covering darkness, nor in the earth’s embrace, nor in the mountain forest, nor in the water’s depths—go where she will. Have thou, as I expect from thee, patience for all thy woes this day.”

The aged one leaped up then; thanked God, the mighty Lord, for what the man spoke. Then Hrothgar’s horse was bitted, the steed with twisted mane. The wise prince went forth in splendour; the foot-troop of shield-bearing warriors stepped forward. The tracks were widely seen along the forest paths, the course over the fields. Away over the dark moor she went; she bore the best of thanes, reft of life, who with Hrothgar ruled the land. Then the son of princes strode over the high rocky cliffs, the narrow paths, the straitened tracks, the unknown road, the steep crags, many a monster’s abode. He with a few other wise men went ahead to spy out the land, until suddenly he found the mountain trees hanging above the grey rock. The water beneath lay blood-stained and troubled. All the Danes, the friends of the Scyldings, were mournful in mood; many a thane had to suffer; there was sorrow for many of the earls, when they found Æschere’s head on the cliff by the mere.

The flood surged with blood, with hot gore; the people beheld it. At times the horn sang its eager war-song. The troop all sat down; then they saw along the water many of the dragon kind, strange sea-dragons moving over the mere, also monsters lying on the rocky headlands; then at midday the dragons and wild beasts often go on a sorrowful journey on the sail-road. They fell away bitter and angered; they heard the clang, the war-horn sounding. The prince of the Geats with his bow parted one of them from life, from the struggle of the waves, so that the stout war-shaft stood in his heart. He was the more sluggish at swimming in the water, because death carried him off. Speedily the wondrous wave-dweller was hard pressed in the waves with boar-spears of deadly barbs, beset by hostile attacks and drawn out on the headland. The men beheld the dread creature.

Beowulf clad himself in warrior’s armour; he lamented not his life. The war-corslet, hand-woven, broad, cunningly adorned, must needs try the water; it knew how to guard his body so that the grip of war might not wound his heart, the malicious clutch of an angry foe his life. And the gleaming helmet, which was to mingle with the depths of the mere, to seek the welter of the waves, decked with treasure, circled with diadems, as the smith of weapons wrought it in days long past, wondrously adorned it, set it round with boar-images, guarded his head so that no sword or battle-blades could pierce it. That was not the least then of mighty helps that Hrothgar’s squire lent him in his need. That hilted sword was called Hrunting; it was an excellent old treasure; the brand was iron, marked with poisonous twigs, hardened in the blood of battle. It never failed any men in war who seized it with their hands, who ventured to go on dire journeys, to the meeting-place of foes. That was not the first time that it was to accomplish a mighty deed.

In truth the son of Ecglaf mighty in strength did not remember what erstwhile he spoke when drunken with wine, when he lent the weapon to a better sword-warrior. He himself durst not risk his life beneath the tossing of the waves, accomplish heroic deeds. There he forfeited fame, repute for might. Not so was it with the other when he had clad himself for war.

XXIII

Beowulf spoke, son of Ecgtheow: “Consider now, famous son of Healfdene, wise prince, gold-friend of warriors, now I am ready for the venture, what we spoke of a while since; if I should depart from life in thy cause, that thou shouldst ever be in the place of a father when I am gone. Be thou a guardian to my followers, my comrades, if war takes me. Likewise, dear Hrothgar, do thou send the treasures thou hast given me to Hygelac. The lord of the Geats may perceive by that gold, the son of Hrethel may see when he looks upon that treasure, that I found an excellent good giver of rings, that I took joy while I could. And do thou let Unferth have the ancient blade, the far-famed man have the precious sword with wavy pattern and sharp edge; I shall achieve fame for myself with Hrunting, or death will carry me off.”

After those words the prince of the Weder-Geats hastened exceedingly; he would in no wise wait for an answer. The surge of waters received the war-hero. Then there was a spell of time ere he might behold the bottom of the mere.

She who had held for fifty years the domain of the floods, eager for battle, grim and greedy, discovered straightway that a man was seeking from above the dwelling of monsters. She reached out against him then, seized the warrior with dread claws; nevertheless she injured not the sound body; the ring-mail guarded it round about so that she could not pierce the corslet, the locked mail-shirt, with hostile fingers. When she came to the bottom, the sea-wolf bore the prince of rings to her lair, so that he could not (yet was he brave) use weapons; and too many monsters set upon him in the water, many a sea-beast rent his war-corslet with battle-tusks; they pursued the hero. Then the earl noticed he was in some kind of hostile hall, where no water in any way touched him, nor could the sudden clutch of the flood come near him because of the roofed hall; he saw the light of fire, a gleaming radiance shining brightly.

Then the valiant one perceived the she-wolf of the depths, the mighty mere-woman; he repaid the mighty rush with the battle-sword; the hand drew not back from the stroke, so that the sword, adorned with rings, sang a greedy war-chant on her head. Then the stranger found that the sword would not bite or injure life, but the edge failed the prince in his need. It had endured in times past many battles, often had cut through the helmet, the mail of a doomed man. That was the first time for the costly treasure that its repute failed.

Once again the kinsman of Hygelac was resolute, mindful of heroic deeds, no whit lax in courage. Then the angry warrior cast down the sword with its twisted ornaments, set round with decorations, so that it lay on the ground, strong and steel-edged. He trusted in his strength, his mighty hand-grip. Thus a man must needs do when he is minded to gain lasting praise in war, nor cares for his life.

Then the prince of the War-Geats seized Grendel’s mother by the hair; he feared not the fight. Then stern in strife he swung the monster in his wrath so that she bent to the ground. She quickly gave him requital again with savage grips, and grasped out towards him. Weary in mood then she overthrew the strongest of fighters, the foot-warrior, so that he fell down. Then she sat on the visitor to her hall, and drew her knife, broad and bright-edged; she was minded to avenge her child, her only son. The woven breast-net lay on his shoulder; that guarded his life; it opposed the entrance of point and edge. Then the son of Ecgtheow, the hero of the Geats, would have found death under the wide waters if the war-corslet, the stout battle-net, had not afforded him help, and if holy God, the wise Lord, had not achieved victory in war; the Ruler of the heavens brought about a right issue, when once more he stood up with ease.

XXIV

He saw then among weapons a victorious blade, an old sword of giants, strong in its edges, the glory of warriors. That was the choicest of weapons; save only it was greater than any other man could bear to the battle-play, trusty and splendid, the work of giants. The hero of the Scyldings, angered and grim in battle, seized the belted hilt, wheeled the ring-marked sword, despairing of life; he struck furiously, so that it gripped her hard against the neck. It broke the bone-rings; the blade went straight through the doomed body. She fell on the floor. The brand was bloody; the man rejoiced in his work.

The gleam was bright, the light stood within, just as the candle of the sky shines serenely from heaven. He went along the dwelling; then he turned to the wall; Hygelac’s thane, raging and resolute, raised the weapon firmly by its hilts. The sword was not useless to the warrior, but he was minded quickly to requite Grendel for the many onslaughts which far more than once he made on the West-Danes, when he slew Hrothgar’s hearth-companions in their sleep, devoured fifteen men of the Danish people while they slumbered, and bore away as many more, a hateful sacrifice. He, the furious hero, avenged that upon him there where he saw Grendel lying, weary of war, reft of life, as erstwhile the battle at Heorot despatched him. The body gaped wide, when after death it suffered a stroke, a hard battle-blow: and then he hewed off its head.

Straightway the wise men who gazed on the mere with Hrothgar saw that the surge of waves was all troubled, the water stained with blood. Grey-haired old men spoke together of the valiant man, that they did not expect to see the chieftain again, or that he should come as a conqueror to seek the famous prince. Then it seemed to many that the sea-wolf had slain him. Then came the ninth hour of the day. The bold Scyldings forsook the headland; thence the gold-friend of men departed homewards. The strangers sat sick at heart, and stared at the mere; they felt desire and despair of seeing their friendly lord himself.

Then that sword, the battle-brand, began to vanish in drops of gore after the blood shed in fight. That was a great wonder, that it all melted like ice when the Father loosens the bond of the frost, unbinds the fetters of the floods; He has power over times and seasons. That is the true Lord.

The prince of the Weder-Geats took no more of the precious hoardings in those haunts, though he saw many there, save the head and with it the treasure-decked hilts. The sword had melted before, the inlaid brand had burned away, so hot was that blood and so poisonous the alien spirit who died in it. Straightway he fell to swimming; he, who before in the struggle endured the fall of foes, dived up through the water. The wave-surges were all cleansed, the great haunts where the alien spirit gave up his life and this fleeting state.

Then the protector of sea-men, brave-minded, came swimming to land; he took pleasure in the sea-booty, in the mighty burden which he bore with him. They went to meet him, the excellent troop of thanes; they thanked God; they rejoiced in the prince, that they could behold him safe and sound. Then helm and corslet were loosed with speed from off the brave man; the lake lay still, the water under the clouds, stained with the blood of battle.

They set out thence on the foot-tracks, joyous at heart; they paced the path, the well-known street. Men nobly bold bore the head from the cliff with toil for each of the very brave ones. Four men with difficulty had to carry Grendel’s head to the gold-hall on the battle-spear, until of a sudden the fourteen brave warlike Geats came to the hall; their lord trod the fields about the mead-hall with them, fearless among his followers.

Then the prince of thanes, the man bold in deeds, made glorious with fame, the hero terrible in battle, came in to greet Hrothgar. Then Grendel’s head was borne by the hair into the hall where the men were drinking—a dread object for the earls and the queen with them; the men looked at the wondrous sight.

XXV

Beowulf spoke, son of Ecgtheow: “Lo! son of Healfdene, prince of the Scyldings, we have brought thee with pleasure, as a token of glory, these sea-trophies which thou beholdest here. Scarcely did I survive that with my life, the struggle beneath the water, barely did I accomplish the task, the fight was all but ended, if God had not protected me.

“I could do naught with Hrunting in the fight, though that weapon is worthy, but the Ruler of men vouchsafed that I should see a huge old sword hang gleaming on the wall—most often He has guided those bereft of friends—so that I swung the weapon. Then in the struggle I slew the guardians of the house when the chance was given me. Then that battle-brand, the inlaid sword, burned away as soon as the blood spurted out, hottest battle-gore. Thence from the foes I carried off that hilt; I avenged, as was fitting, the deeds of malice, the massacre of the Danes.

“So I promise thee that thou mayest sleep in Heorot, free from sorrow with the band of thy warriors and all the thanes among thy people, the youths and veterans; that thou, prince of the Scyldings, dost not need to dread death for the earls from the quarter thou didst formerly.”

Then the gold hilt, the ancient work of giants, was given into the hands of the old warrior, the grey-haired leader. It came into the possession of the prince of the Danes, the work of cunning smiths, after the death of the monsters, and after the creature of hostile heart, God’s foe, guilty of murder, and his mother also had left this world. It came into the power of the best of mighty kings between the seas who dealt out money in Scandinavia.

Hrothgar spoke; he beheld the hilt, the old heirloom. On it was written the beginning of a battle of long ago, when a flood, a rushing sea, slew the race of giants; they had lived boldly; that race was estranged from the eternal Lord. The Ruler gave them final requital for that in the surge of the water. Thus on the plates of bright gold it was clearly marked, set down and expressed in runic letters, for whom that sword, the best of blades, was first wrought with its twisted haft and snake images.

Then the wise man spoke, the son of Healfdene. All were silent. “Lo! he who achieves truth and right among the people may say that this earl was born excellent (the old ruler of the realm recalls all things from the past). Thy renown is raised up throughout the wide ways, my friend Beowulf, among all peoples. Thou preservest all steadfastly, thy might with wisdom of mind. I shall show thee my favour, as before we agreed. Thou shalt be granted for long years as a solace to thy people, as a help to heroes.

“Not so did Heremod prove to the sons of Ecgwela, the honourable Scyldings; his way was not as they wished, but to the slaughter and butchery of the people of the Danes. Savage in mood he killed his table-companions, his trusty counsellors, until he, the famous prince, departed alone from the joys of men, although mighty God had made him great by the joys of power and by strength, had raised him above all men. Yet there grew in his heart a bloodthirsty brood of thoughts. He gave out no rings to the Danes according to custom; joyless he dwelt, so that he reaped the reward of his hostility, the long evil to his people. Learn thou by this; lay hold on virtue. I have spoken this for thy good from the wisdom of many years.

“It is wonderful to tell how mighty God with his generous thought bestows on mankind wisdom, land and rank. He has dominion over all things. At times He allows man’s thoughts to turn to love of famous lineage; He gives him in his land the joys of domain, the stronghold of men to keep. He puts the parts of the world, a wide kingdom, in such subjection to him that he cannot in his folly conceive an end to that. He lives in plenty; nothing afflicts him, neither sickness nor age; nor does sorrow darken his mind, nor does strife anywhere show forth sword-hatred, but all the world meets his desire.

XXVI

“He knows nothing worse till within him his pride grows and springs up. Then the guardian slumbers, the keeper of the soul—the sleep is too heavy—pressed round with troubles; the murderer very near who shoots maliciously from his bow. Then he is stricken in the breast under the helmet by a sharp shaft—he knows not how to guard himself—by the crafty evil commands of the ill spirit. That which he had long held seems to him too paltry, he covets fiercely, he bestows no golden rings in generous pride, and he forgets and neglects the destiny which God, the Ruler of glory, formerly gave him, his share of honours. At the end it comes to pass that the mortal body sinks into ruin, falls doomed; another comes to power who bestows treasures gladly, old wealth of the earl; he takes joy in it. Keep thyself from such passions, dear Beowulf, best of warriors, and choose for thyself that better part, lasting profit. Care not for pride, famous hero. Now the repute of thy might endures for a space; straightway again shall age, or edge of the sword, part thee from thy strength, or the embrace of fire, or the surge of the flood, or the grip of the blade, or the flight of the spear, or hateful old age, or the gleam of eyes shall pass away and be darkened; on a sudden it shall come to pass that death shall vanquish thee, noble warrior.

“Thus have I ruled over the Ring-Danes under the heavens for fifty years, and guarded them by my war-power from many tribes throughout this world, from spears and swords, so that I thought I had no foe under the stretch of the sky. Lo! a reverse came upon me in my land, sorrow after joy, when Grendel grew to be a foe of many years, my visitant. I suffered great sorrow of heart continually from that persecution. Thanks be to God, the eternal Lord, that I have survived with my life, that I behold with my eyes that blood-stained head after the old struggle. Go now to the seat, enjoy the banquet, thou who art made illustrious by war; very many treasures shall be parted between us when morning comes.”