The Vatican area is easily accessible on foot from the centro storico via the pedestrian Ponte Sant’Angelo, which leads to the Castel Sant’Angelo. A short walk away are the Vatican Museums and St Peter’s. The area is also well served by buses, trams and Metro Line A, which stops at Ottaviano San Pietro for the Vatican. Nearby, Via Ottaviano and Via Cola di Rienzo are major high-street shopping areas. The area is almost always busy – start your day before St Peter’s opens to avoid the crowds.

1. Vatican City

Miniature state

Fountain, Piazza San Pietro

With an area of just 0.3 sq km (0.1 sq mile) and a population of 800 people, the Vatican City is the smallest country in the world. The borders of the state are marked by the walls that encircle the papal palaces and gardens, the colonnade that surrounds Piazza San Pietro and by a white line between the end of the piazza and the beginning of Via della Conciliazione. The Vatican has its own railway station, police force, heliport, post office, radio station and newspaper. Take a lift or climb stairs to the roof of St Peter’s, the best place from which to view the whole of this tiny state.

Key Sights

2. Radio Vaticana The Vatican’s radio, TV and web TV are broadcast in 39 languages from this tower, part of the Leonine Wall built in AD 847.

3. Sistine Chapel This chapel, with its famous ceiling, is where cardinals convene to elect the new pope.

6. Apostolic Palace The pope appears on the balcony of the Apostolic Palace – his official residence – at noon on Sundays to give the gathered crowds his blessing.

7. Via della Conciliazione This straight boulevard, lined with shops selling religious souvenirs, was laid out by Mussolini as a symbolic link between the new Vatican state and Italy after the signing of the Lateran Pacts in 1929.

12. Papal Audience Chamber The pope meets with an audience here on most Wednesday mornings.

14. Vatican Railway Station The Vatican has the shortest national railway line in the world. Just 300 m (1,000 ft) long, it is used mostly for freight, and connects with the Italian railway network.

Left

Piazza San Pietro Middle Vatican gardens Right Egyptian obelisk

Kids’ Corner

Water on the ropes!

The obelisk in the centre of the Piazza San Pietro was moved to its present position on the orders of Pope Sixtus V. A great crowd watched in silence as 900 men, with 150 horses and 47 winches, set about moving the obelisk – the pope had announced that he would execute anyone who made a sound. All went well until they began to haul the obelisk upright into its new position. The ropes were stretched so taut that they seemed ready to snap. Suddenly the words “Water on the ropes!” shattered the silence. The advice was followed and the obelisk was safely set into place.

154-piece suit

The pope is protected by an army of about a hundred Swiss Guards, who can been seen dressed in their ceremonial costume at the Vatican’s gates. When a new tailor was appointed to the Vatican in 2006, he discovered that there was no pattern for the Swiss Guards’ uniform. He and his wife took an old uniform apart in order to see how it had been made, and found that it was made up of 154 pieces!

Millennium babies

As part of the millennium celebrations in 2000, Via della Conciliazione’s streetlamps were connected to Rome’s maternity units on Christmas Eve. Every time a baby was born, the lights began to pulse slowly. A plaque set into the pavement on the left as you approach St Peter’s records the event.

2. St Peter’s

Bullet-proof statue and ice cream on the roof

The centre of the Roman Catholic faith and the largest church in the world, St Peter’s draws pilgrims from all over the globe. A 4th-century church marked the site where St Peter was martyred and buried, but in the 16th century, Pope Julius II commissioned Bramante to replace the old church with a grand new basilica. The church took over a 100 years to build, cost the equivalent of £460 million in today’s money and involved all the great Roman Renaissance and Baroque artists and architects – not only Bramante, but also Raphael, Bernini and Michelangelo. It was finally completed in 1626.

Key Features

1. Roof Take the lift to the roof, where the sampietrini (workers responsible for the maintainance of the church and their families) lived in the old days.

4. Statue of Emperor Constantine A dramatic statue of Emperor Constantine upon a rearing horse captures the moment in which he had a vision of the Cross during the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312.

5. Porta Santa This Holy Door, open only during Holy Years, was last used in 2000.

Left

Spectacular dome designed by Michelangelo Middle Michelangelo’s Pietà Right Bernini’s baldacchino

Kids’ Corner

Holy tour!

-

Look up inside St Peter’s dome. It is 41 m (136 ft) across and 137 m (448 ft) high.

-

Look for the bronze markers in the floor showing the inferior length of other cathedrals – they are not accurate: Milan cathedral is 20 m (66 ft) longer than marked!

-

Kiss the foot of the bronze statue of St Peter to gain a 50-day indulgence (a discount on time served in purgatory, heaven’s waiting room).

-

Bernini’s colonnade was designed so that the wealthy could approach St Peter’s in their carriages, sheltered from the weather.

St Andrew’s snail

The staircase curling around the inside of the dome is known as the Lumaca di Sant’Andrea. “Lumaca” means snail, and Andrea, or Andrew, was St Peter’s brother.

Holy or unholy?

Holy Years or ordinary jubilees are traditionally held every 25 or 50 years. However, the pope can announce one to mark a special event. These are known as extraordinary jubilees. The last jubilee was the “Great Jubilee” in the year 2000 – two millennia after the birth of Christ. The next Holy Year is not yet known.

Bearded queen

One of the few women to be buried inside St Peter’s is Queen Christina of Sweden, who moved to Rome in 1655 after renouncing Protestantism and abdicating her throne. Her statue is very elegant, although it seems that she was not. According to an observer, “She is exceeding fat… and she has a double chin from which sprout a number of isolated tufts of beard…”.

3. Vatican Museums

Take a tour with an angel

Statue of Venus, Vatican Museums

With no fewer than 12 museums, the Vatican’s complex of museums is the largest in the world and contains far more than any adult, let alone child, could absorb. The complex has two signposted routes – one takes in the most popular museums, including the Sistine Chapel and the Raphael Rooms, and the other everything else. The most enjoyable way to explore the museums is to rent a Family Audioguide, which has a series of narrator-guides ranging from a Melozzo da Forlì angel to Michelangelo. The museums also have excellent information boards in Italian and English.

Key Sights

3. Room of the Animals Roman mosaics decorate the walls and floors of this room, which is devoted entirely to sculptures of animals. (see Pio-Clementino Museum)

10. Gallery of the Candelabra Once an open loggia, this gallery of Greek and Roman sculpture has a fine view of the Vatican Gardens.

Cortile della Pigna Named after a giant pine cone flanked by two bronze peacocks and dominated by the Sphere within a Sphere – a revolving bronze sculpture by Arnaldo Pomodoro – this beautiful courtyard is the most pleasant place to relax in between exploring the complex of museums.

Left

Gallery of the Maps Middle Spiral staircase Right Gallery of the Candelabra

Kids’ Corner

Can you find…

-

A bird pecking at a dead rabbit?

-

Two bronze peacocks?

-

An upside-down world?

-

The Popemobile?

-

An open mummy case and mummy?

Museum stroll

If you visit every single museum in the Vatican Museum complex, you will have ended up walking over 7 km (4 miles).

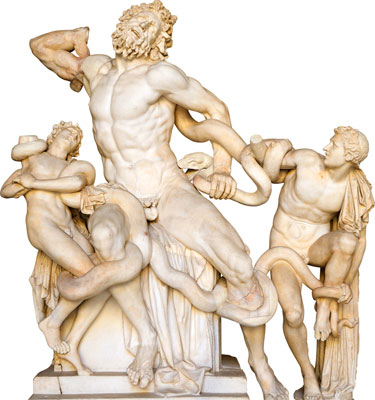

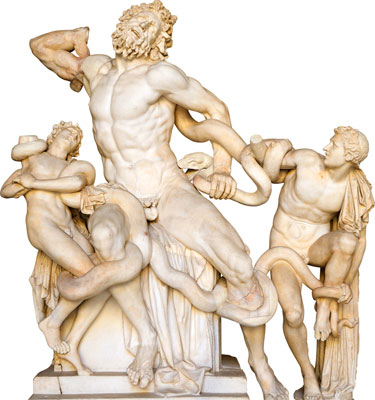

Laocoönomania

The

Laocoön, on display in the

Cortile Ottagonale, captured the Renaissance imagination to such a degree that it even became a fashion item – Isabella d’Este, the Marchesa of Mantua, ordered a

Laocoön logo for her hat.

Costly sphere

Arnaldo Pomodoro’s Sphere within a Sphere was commissioned by the Vatican in 1990 and cost €5 million. It is made of about the same amount of solid bronze that was used to create the orb on the top of St Peter’s. Sit down and watch the changing reflections of the statue’s surroundings as it rotates.

Vatican Museums continued

Sistine Chapel Ceiling

In 1508, Pope Julius II decided that the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel needed repainting. The walls of the chapel were already covered with frescoes, but the ceiling was simply blue sprinkled with golden stars. Michelangelo spent the next four years painting 366 figures on the ceiling of the chapel, illustrating the biblical stories of the Creation of the World, the Fall of Man and the Coming of Christ. Julius was exasperated by how long Michelangelo was taking. “When will you finish?” he railed. “When I can,“ replied Michelangelo.

1. God Dividing Light from Darkness Michelangelo represents God as a blurry figure barely emerging from the chaos – on one side of him is darkness, and on the other, light. According to Genesis, it was on the first day that God divided light from darkness.

2. God Creates the Sun and the Moon A more defined God creates the sun with one hand and the moon with his other. A patch of green in the bottom left corner shows life beginning on earth.

3. God Separates the Waters from the Land God is shown pushing water away from land. According to the Bible, God created the sun and moon after he separated water from land.

4. Creation of Adam God reaches down from a cloudy heaven to create Adam, who is shown lying on land, beside water.

5. Creation of Eve Eve is shown emerging from Adam’s rib as he sleeps.

6. The Fall of Man This is a two-part story. In the first part, Eve is tempted by Satan – shown as a snake with the body of a woman – to reach for the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge. In the second half Satan expels Adam and Eve from Paradise.

7. The Sacrifice of Noah This scene shows Noah sacrificing a sheep to God before the Great Flood. However, in the Bible, Noah’s sacrifice was made after the flood, not before. It is unclear why Michelangelo changed the order of the story.

8. Flood God, angry at human behaviour floods the world. Michelangelo shows land occupying the same corner of the panel as it does in God the Sun and the Moon and the Creation of Adam, maybe to emphasize that the world could be destroyed as well as created.

9. Drunkenness of Noah After the Flood, Noah became a farmer and planted a vineyard. In an episode whose significance remains obscure, Noah is shown getting drunk on the wine he has made.

10. Old Testament Scenes of Salvation During the Renaissance, certain Old Testament events and figures were considered to predict the Coming of Christ. In the four corners of the ceiling are Esther, Judith, David and Moses – all of whom had saved their people by killing an evil or monstrous enemy – a symbolic echo of Christ triumphing over evil.

11. The Sibyls The Sibyls, such as the Delphic Sibyl, were figures from pagan mythology, who had the power to see into the future. In the Renaissance, they were adopted by Christian artists and writers. The future these Christianied Sibyls could see was the Coming of Christ.

Kids’ Corner

Candy-coloured fortune-tellers

Look up at the Prophets and Sibyls seated around the edge of the ceiling and imagine that their luscious shot-silk robes are really sweets and ice cream.

Find out who is dressed in:

strawberry and lime

lemon and lime

blackcurrant and orange

strawberry and pistacchio

tangerine and apricot

orange and lime

Trust no one

Michelangelo decided to take no chances with his scaffolding – rather than trusting anyone else to build it, he designed it himself!

Prophet or painter?

The despairing prophet Jeremiah is a self-portrait of Michelangelo, probably expressing the frustration he felt with the impatient and demanding Pope Julius II.

Fresh paint

Fresco means fresh in Italian. The fresco technique involves painting on wet plaster. Every day, a new area of fresh wet plaster was prepared. This area had to be covered in paint before it dried – Adam was painted in three days and his Creator in four. The artist left hogs’ hair from his brushes and even the occasional mucky thumbprint embedded in the paint. He also took short cuts – Adam’s eye is simply unpainted plaster.

Vatican Museums continued

Sistine Chapel Walls

The old and the new

The walls of the Sistine Chapel are decorated with frescoes by artists such as Botticelli, Perugino, Signorelli and Michelangelo’s one-time teacher, Ghirlandaio. The Renaissance fascination with discovering parallels between the Old and New Testaments is clear from these frescoes – on one side are episodes from the life of Christ and on the other are scenes from the life of Moses. The first panels of these frescoes originally began with the Birth of Christ, and its Old Testament parallel, the Finding of Moses, but these were destroyed in 1536 to make room for The Last Judgment.

A key theme in the frescoes is the power of the papacy. Moses was both a spiritual and temporal leader of his people, so he was a convenient example for those who wanted to argue that the pope too should be both. The political message is further emphasized in a scene by Perugino, which shows Jesus handing over the keys of the kingdoms of both Heaven and Earth to St Peter.

The Last Judgment

Twenty-four years after he had finished the Sistine Chapel ceiling, Michelangelo was commissioned by Pope Paul III Farnese to create a fresco of The Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. It is a bleak, harrowing work, reflecting the pessimism Michelangelo himself felt at the time, showing the damned hurtling towards a putrid hell and the blessed being dragged up to heaven. Saints demand vengeance for their martyrdoms, and Christ is shown as an unusually pitiless figure, with the Virgin sitting helpless beside him. Michelangelo drew from Dante’s Inferno – he shows the ferryman, Charon, pushing passengers off his boat with an oar into the fiery depths of Hell.

The Council of Trent, responsible for deciding what was permissible in religious art, objected to the painting. One of the pope’s own officers, Biagio da Cesena, thought it was disgraceful that Michelangelo had included so many nude figures, and declared that the painting was suitable not for a chapel but rather “for the public baths and taverns”. Michelangelo retaliated by painting Cesena as Minos, judge of the underworld, on the far bottom-right corner of the painting with donkey ears and in the grip of a coiled snake. Apparently, when Cesena complained to the pope, he said he could do nothing since his jurisdiction did not extend to hell. Michelangelo included a portrait of himself too in the fresco – his face can be seen on the flayed skin held by St Bartholomew.

Michelangelo’s famous The Last Judgment on the Sistine Chapel walls

Raphael Rooms

Thieves in the temple, Greeks in the bath

In 1508, Pope Julius II decided to have a suite of four rooms that had already been frescoed by artists such as Piero della Francesca, redecorated. Julius asked his favourite architect, Bramante, to recommend some new artists and in 1509, after a long trial, Bramante suggested he call in a young artist named Raphael. The work took over 16 years and Raphael died before its completion.

Hall of Constantine

Raphael had very little to do with the paintings in this hall – most of the work was done by his pupils. As a result, they are not held in the same high regard as those in the other rooms. The theme is the triumph of Christianity over paganism, with the four main frescoes focusing on key moments in Emperor Constantine’s life. These include the Vision of the Cross and The Battle of the Milvian Bridge.

Room of Heliodorus

The theme of the next room is divine intervention.

The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple shows two flying youths and a rider on a rearing horse felling Heliodorus, a thief, as he tries to escape after robbing a temple. The theme continues in the dazzlingly lit

Liberation of St Peter, in which an angel is shown freeing St Peter (Pope Julius) from prison. The chains depicted are now on display in the church of

San Pietro in Vincoli, where Julius had been assigned as a Cardinal.

Room of the Segnatura

The first room to be painted was the Room of the Segnatura. The frescoes in this room effectively bring together Christian and pagan themes to celebrate a rather optimistic, and very typical, idea, drawing from the Renaissance – the ability of the intellect to discover the truth. The most famous of the frescoes is the School of Athens, in which the artist painted his contemporaries as Greek philosophers in a vaulted hall, somewhat like the Baths of Diocletian.

Room of The Fire in the Borgo

Pope Julius had passed away by the time work began on the Room of The Fire in the Borgo, and the theme was selected by his successor, Pope Leo X. The most famous fresco here is The Fire in the Borgo, which celebrates the miracle that took place in 847, when the then pope, Leo IV extinguished a fire in the quarters around the Vatican, by making the sign of the cross. Leo X considered the event to be a reflection of his own success in extinguishing the flames of the wars that had recently ravaged Italy. Consequently, the pope standing at the back of the painting with his hand raised was given Leo X’s chubby face.

The Fire in the Borgo, after which one of the Raphael Rooms is named

Kids’ Corner

Can you spot the following in the School of Athens:

-

Leonardo da Vinci as the philosopher Plato?

-

Michelangelo Buonarroti as Heraclitus?

-

Donato Bramante as the geometrician Euclid?

-

Raphael Sanzio as a pupil of Euclid?

-

La Fornarina as the love interest?

Painter’s assistants

Although Raphael designed The Fire in the Borgo, it was painted entirely by his assistants.

Dust-free art

A new wall, which sloped slightly inwards, was erected for The Last Judgment in the hope that it would stop dust from settling on the fresco!

Baby in the Borgo

In The Fire in the Borgo, the image of a baby being passed down from a wall behind which the fire raged made such an impression on Picasso that he incorporated it into Guernica, his semi-abstract rendition of the horrors inflicted by the Nazis when they bombed a town during the Spanish Civil War.

Vatican Museums continued

Pio-Clementino Museum

Copycat sculptures

The Vatican’s prize pieces of Greek and Roman sculpture form the nucleus of the 18th-century Pio-Clementino Museum. Most of these are Roman copies of famous, but lost, ancient Greek works. In the pavillions of the Cortile Ottagonale and surrounding rooms are sculptures considered among the greatest achievements of Western art. These include the dramatic and exciting Laocoön, a violently contorted Hellenistic work (3rd century BC) showing the Trojan priest, Laocoön, and his two sons struggling to escape from the writhing coils of a sea serpent. In contrast is the elegant, aloof Apollo del Belvedere, believed by Renaissance artists to be a paragon of physical perfection.

Opening straight off the courtyard is the Room of the Animals, which has a stone menagerie of beasts ranging from pigs and sheep to horses and lions, with an animal-themed Roman mosaic floor to match. Beyond this is the muscular Belvedere Torso, whose influence on Michelangelo can be seen in some of the mysterious Ignudi on the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling. Fittingly, the collection also includes a Roman copy of the Aphrodite of Cnidias – considered to be the most perfect sculpture of a woman in existence.

Laocoön, one of the most famous sculptures in the Pio-Clementino Museum

Egyptian Museum

From the land of the Nile

As is evident from the number of obelisks in the city, all things Egyptian were extremely popular in ancient Rome. The collection in this museum consists chiefly of Egyptian antiquities brought to Rome to adorn buildings such as the Temple of Isis which once stood near the

Pantheon,

Villa Adriana at Tivoli and the Gardens of Sallust to the southeast of the Villa Borghese park. The Canopus Serapeum, a temple from Villa Adriana, has been rebuilt here. Among the statues found in it are a bust of Isis, and a statue of Hadrian’s lover, Antinous, as the god Osiris. In the hemicycle overlooking the giant pine cone of the Cortile della Pigna (which came from the Temple of Isis) are more statues of Isis, several of the lioness-goddess Sekhmet and baboon-god Bes, along with one of Caligula’s sister, Drusilla, in the guise of the Egyptian Queen Arsinoe II.

More interesting are the Egyptian objects, which include gloriously painted mummy cases; a mummy with an exposed shrivelled face, hands and feet; several Canopic jars and finds from a tomb – pieces of bread, cereal grains, a pair of sandals and a nit-comb.

Pinacoteca

From Fabriano to Pinturicchio

Many important works of art by Renaissance masters are on display in the 18 rooms of the Pinacoteca. The art collection in this gallery is unmatched by any other in the Vatican City, or for that matter, Rome. Exhibits include the beautiful 15th-century Stories of St Nicholas of Bari by Gentile da Fabriano. On display in Room II, this painting is of four episodes from the life of St Nicholas of Bari. One of these scenes shows the saint throwing golden balls through a window to three poor girls – two balls are on the bed, while the saint is shown aiming the third at a red sock that one of the girls is removing from her father’s foot – this started the tradition of hanging up stockings at Christmas.

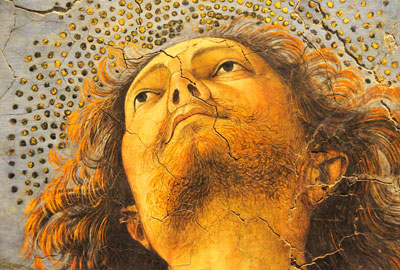

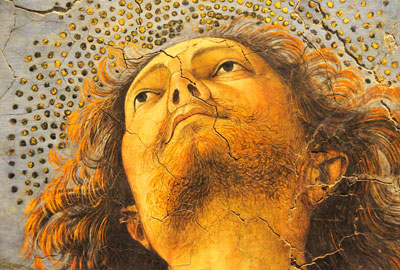

Walk through to Room IV to see works of art by Melozzo da Forlì, including the fragments of a fresco of an orchestra of angels created by the artist around 1472. On the way, stop by Room III to see the gorgeous romantic Madonnas by the monks Filippo Lippi and Frà Angelico. Go to Room VI, devoted to the fabulous world of the Crivelli brothers – 16th-century Venetian artists who painted doll-like Madonnas, and created ornate frames carved with fruits to display them in.

Raphael has a whole room (Room VIII) dedicated to his work, the most arresting of which is Transfiguration, dominated by a stunning woman with lustrous red-gold hair who is thought to be La Fornarina, his love interest. The next room features a single, rare work by Leonardo Da Vinci. This is an unfinished St Jerome, showing the ancient, emaciated saint who went on a retreat to the desert with only a lion for company. Beyond, in Room X, is the Vision of St Helena, a painting by the 16th-century Venetian artist, Veronese. Veronese always set religious scenes in contemporary Venice, and Helena is no exception, dressed as a weary Venetian contessa, leaning heavily on the True Cross that she had discovered, according to legend, in the Holy Land. Introducing his usual note of realism, Caravaggio is represented in Room XII by the Deposition, in which two men heave Christ’s slumped body from the cross as Magdalene weeps into a handkerchief and Mary looks on with quiet disbelief.

A portion of a fresco by Melozzo da Forlì, Pinacoteca

Kids’ Corner

Can you find…

-

Evidence that nits are an ancient problem?

-

Fruity Madonnas?

-

The very first Christmas stocking?

-

Stone pigs and mosaic squid?

Bathing beauty?

The Laocoön was brought to Rome from the island of Rhodes in AD 69 to adorn the Baths of Titus, where it doubtless made any Roman of a nervous disposition think twice before plunging into the water!

For the love of a goddess

In the 4th century BC the Greek sculptor Praxiteles shocked the people of Kos by creating the world’s first nude statue of the goddess Aphrodite (Venus to the Romans) leaving her bath – a copy of which is on display in the Pio-Clementino museum. It was decided that the statue was far too revealing to be put on public display, so it was sold to the Cnidians – it is said that several Cnidians did fall in love with the stone goddess, and even tried to kiss her!

4. Castel Sant’Angelo

Mausoleum, fortress and prison

Ponte Sant’Angelo and the castle

A huge brick cylinder rising from the banks of the Tiber, Castel Sant’Angelo began life as a mausoleum for Emperor Hadrian. Since then it has played several roles: as part of a city wall, as a medieval citadel, as a prison and as a retreat for popes in times of danger. In summer, it is possible to follow the popes’ Vatican escape route along a secret passageway. The most theatrical approach to the castle is from across the Ponte Sant’Angelo, a bridge adorned with marble statues of angels by Bernini.

Key Features

1. The Treasury Part of the original Roman mausoleum, this circular room was used as a treasury in later centuries and then as a prison. From here a narrow staircase cut into the Roman walls leads to the roof.

4. Hall of Justice Giordano Bruno was among those put on trial here. It now holds prisoners’ chains and arms, including hand grenades and a collection of hollow glass and terracotta cannonballs.

6. Hall of the Urns This chamber held urns containing the ashes of Hadrian, his wife and son, and was encased with precious marble.

7. Diametric Staircase Built by Pope Alexander VI, this staircase cuts right through the heart of the building.

8. Helicoidal Ramp This spiralling ramp (helicoid is Greek for spiral) dates back to Roman times and was the entrance to emperor Hadrian’s Mausoleum.

. Historic Armoury The armoury, located on the second level, hosts a wide range of weaponry of the times, such as a 15th-century cannon, 17th-century armour and elaborate 16th-century pistols, their walnut handles inlaid with unique designs

. Sala Paolina This is one of a suite of rooms decorated for Pope Paul III Farnese, with illusionistic frescoes including one of a courtier entering the room through a painted door.

. Terrazza dell’Angelo Peter Verschaffelt’s large bronze statue of an angel, cast in 1752, rises from a base of travertine and dominates the Terrazza dell’Angelo.

Left

Historic Armoury Middle Sala Paolina Right Terrazza dell’Angelo

Kids’ Corner

Can you find…

-

A secret door disguised as a staircase?

-

A virtual courtier?

Lift for Leo X

The shaft of the 16th-century lift, built for Pope Leo X, still has the wooden grooves that guided the cabin up and down.

Watch out – it’s raining hot oil!

Gouged into the mausoleum’s walls are two rooms that housed the castle’s oil reserves. Oil was used for cooking, lighting and – in times of siege – was brought to boiling point and poured into the gutters where it rained on the heads of the attackers. Ouch!

From hero to anti-hero!

Goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini claimed to have defended the castle single-handedly when it was being sacked by Germans, while at the same time finding time for a spot of needlework – he concealed the pope’s jewels by sewing them into his clothes. He was later accused of stealing some of those jewels and was imprisoned in one of the castle’s five prisons. The room in which he was confined was one of three tanks in which water from the Tiber was collected and filtered until 1570, when the Acqua Vergine aqueduct was re-opened. Eventually, he escaped through the latrine, shinning down the 25-m (82-ft) wall on a rope of knotted sheets.