UN Security Efforts During the Cold War

THE UN CHARTER’S REQUIREMENT for unanimity among the permanent members of the Security Council reflected the realities of the power politics of the day and historical norms of European interstate relations. The council was created less out of naive idealism and more out of a hardheaded effort to mesh state power with international law, a traditional approach to effective enforcement. However, the underlying requirement that members would agree was not borne out with any frequency until after the Cold War. The veto held by the P-5 was not the real problem; disagreement among those with power was.

THE EARLY YEARS: PALESTINE, KOREA, SUEZ, THE CONGO

The onset of the Cold War ended the great-power cooperation on which the postwar order had been predicated. Nonetheless, the UN became involved in four major security crises: Palestine (1948), Korea (1950), Suez (1956), and the Congo (1962). After Israel declared its independence in 1948, war broke out between it and its four neighbors: Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Soon thereafter, the Security Council ordered a cease-fire under Chapter VII and ultimately created an observer team, the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO), under Chapter VI to supervise it. UNTSO observer groups were deployed, unarmed, along the borders of Israel and its neighbors and operated with the consent of the parties involved. Close to six hundred observers were eventually deployed, including army units from Belgium, France, the United States, and Sweden. Troops had no enforcement mandate or capability, but their presence did deter truce violations. To exercise their mandates without relying on military might, they relied on the moral authority of the United Nations. Also, warring parties knew that their truce violations would be objectively reported to UN headquarters in New York for possible further action. Although observers wore the uniforms of their respective national armies, their first allegiance theoretically was to the world organization, symbolized by UN armbands. Later, blue helmets and berets became the trademark of UN peacekeepers. The observers were paid by their national armies and granted a stipend by the world organization. UNTSO’s activities continue to be financed from the UN’s regular operating budget.

UNTSO has performed a variety of important tasks. UNTSO observers set up demilitarized zones along the Israeli-Egyptian and Israeli-Syrian borders, established Mixed Armistice Commissions along each border to investigate complaints and allegations of truce violations, and verified compliance with the General Armistice Agreements. UNTSO did, unfortunately, also contribute to a freezing of the conflict. From 1949 to 1956 and then to 1967, the main parties to the conflict were unwilling to use major force to break apart the stalemate. UNTSO was there to police the status quo. Being freed from major military violence, the parties lacked the necessary motivation to make concessions for a more genuine peace. This problem of UN peacekeeping contributing to freezing but not solving a conflict was to reappear in Cyprus and elsewhere.

The first coercive action taken in the name of the United Nations concerned the Korean peninsula and was arguably a type of collective security.1 World War II left Korea divided, with Soviet forces occupying the North and U.S. forces the South. The UN call for withdrawal of foreign troops and elections throughout a unified Korea was opposed by communist governments, leading to elections only in the South and the withdrawal of most U.S. troops. In 1950, forces from North Korea (the Democratic Republic of Korea), which was informally allied with the Soviet Union and China, attacked South Korea (the Republic of Korea). The United States moved to resist this attack.

At the UN, the USSR was boycotting the Security Council to protest the seating of the Chinese government in Taiwan as the permanent member instead of the Chinese communist government on the mainland. The United States knew the Security Council would not be stymied by a Soviet veto and could adopt some type of resolution on Korea. So Washington referred the Korean situation to the council. The Truman administration ordered U.S. military forces to Korea, albeit before the Security Council approved a course of action. The council passed a resolution under Chapter VII declaring that North Korea had committed a breach of the peace and recommended that UN members furnish all appropriate assistance (including military assistance) to South Korea. The USSR abandoned its boycott and returned to its council seat, thereby thwarting any additional measures. Under U.S. leadership, the General Assembly improvised, through the Uniting for Peace Resolution, to continue support for the South in the name of the United Nations.

Security Council resolutions on Korea provided international legitimacy to U.S. decisions. The Truman administration was determined to stop communist expansion in East Asia. It proceeded without a congressional declaration of war or any other specific authorizing measure, and it was prepared to proceed without UN authorization—although once this was obtained, the Truman administration emphasized UN approval in its search for support both at home and abroad. The General Assembly action deputized the United States to lead the defense of South Korea in the name of the United Nations. When the early tide of the contest turned in favor of South Korea, Truman decided to carry the war all the way to the Chinese border. This was a fateful decision: by bringing Chinese forces into the fight in major proportions, it prolonged the war until 1953, when stalemate restored the status quo ante. All important strategic and tactical decisions pertaining to Korea that carried the UN’s name were made by the United States. Other states, such as Australia and Turkey, fought for the defense of South Korea, but that military effort was a U.S. operation behind the UN flag.

The defense of South Korea was not exactly a classic example of collective security if the UN Charter is the guide. A truncated Security Council clearly labeled the situation a breach of the peace and authorized the use of military force, something that would not occur again during the Cold War. Neither the council nor its Military Staff Committee really controlled the use of UN symbols. No Article 43 agreements transferring national military units to the UN were concluded. And the secretary-general, Trygve Lie of Norway, played almost no role once he declared himself against the North Korean invasion because the Soviet Union stopped treating him as the UN’s head. He was eventually forced to resign (the only such resignation to date) because of his ineffectiveness. Legally correct in his public stand against aggression, he was left without the necessary political support of a major power, Moscow. Subsequent secretaries-general learned from his mistake, representing Charter values but without antagonizing the permanent members whose support was necessary for successful UN action.

The 1956 Suez Canal crisis resulted in the first use of what became known as “peacekeepers” to separate warring parties. France, Britain, and Israel had attacked Soviet-backed Egypt against the wishes of the United States, claiming a right to use force to keep the Suez Canal open after Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser had closed it. Britain and France used their vetoes, blocking action by the Security Council. The General Assembly resorted to the Uniting for Peace Resolution—this time for peacekeeping, not enforcement—and directed Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld (of Sweden) to create a force to supervise the cease-fire between Israel and Egypt once it had been arranged. The first UN Emergency Force (UNEF I) oversaw the disengagement of forces and served as a buffer between Israel and Egypt. In this instance, the United States and Soviet Union were not so far apart. U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower acted in the spirit of collective security by preventing traditional U.S. allies from proceeding with what he regarded as aggression. UN peacekeeping in 1956 and for a decade thereafter was hailed as a success.

The efforts by the world organization to deal with one of the most traumatic exercises in decolonization—in the former Belgian Congo (then Zaire and more recently the Democratic Republic of Congo)—illustrated the limits of peacekeeping. The ONUC (the French acronym for the United Nations Operation in the Congo)2 almost bankrupted the world organization and also threatened its political life. Secretary-General Hammarskjöld lost his own life in a suspicious plane crash in the region.

This armed conflict was both international (caused by Belgium’s intervention in its former colony) and domestic (caused by a province’s secession within the new state). The nearly total absence of a government infrastructure led to a massive involvement of UN civilian administrators in addition to twenty thousand UN soldiers. After having used his Article 99 powers to get the world organization involved, the secretary-general became embroiled in a situation in which the Soviet Union, its allies, and many nonaligned countries supported the national prime minister, who was subsequently murdered while under arrest; the Western powers and the UN organization supported the president. At one point the president fired the prime minister, and the prime minister fired the president, leaving no clear central authority in place. The political vacuum created enormous problems for the United Nations as well as opportunities for action.

Instead of neutral peacekeepers, UN forces became an enforcement army for the central government, which the UN Secretariat created with Western support. This role was not mandated by the assembly or council, and in this process the world organization could not count on cooperation from the warring parties within the Congo. Some troop contributors resisted UN command and control; others removed their soldiers to register their objections. The Soviet Union, and later France, refused to pay assessments for the field operation. This phase of the dispute almost destroyed the UN, and the General Assembly had to suspend voting for a time to dodge the question of who was in arrears on payments and thus who could vote. The USSR went further in trying to destroy Hammarskjöld’s independence by suggesting the replacement of the secretary-general with a troika (or a three-person administrative structure at the top of the organization). Four years later, the UN departed from a unified Congo, an accomplishment. Nevertheless, it had acquired an operational black eye in Africa because of its perceived partisan stance. No UN troops were sent again to Africa until the end of the Cold War (to Namibia). The UN also incurred a large budgetary deficit and developed a hesitancy to become involved in internal wars. Questions about funding lay unresolved, to arise again in later controversies.

The 1973 Arab-Israeli War ended with the creation of the second United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF II). The UNEF model of a lightly armed interpositional force became the blueprint for other traditional peacekeeping operations. UNEF II was composed of troops from Austria, Finland, Ireland, Sweden, Canada, Ghana, Indonesia, Nepal, Panama, Peru, Poland, and Senegal—countries representing each of the world’s four major regions. The operation consisted of over seven thousand persons at its peak. UNEF II’s original mandate was for six months, but the Security Council renewed it continually until 1979, when the U.S.-brokered Israeli-Egyptian peace accord was signed. UNEF II functioned as an impartial force designed to establish a demilitarized zone, supervise it, and safeguard other provisions of the truce. Small-scale force was used to stop those who tried to breach international lines. The presence of UNEF II had a calming influence on the region by ensuring that Israel and Egypt were kept apart. The success of both UNEF I and II, and the problems with the operation in the Congo, catalyzed traditional peacekeeping, the subject to which we now turn.

The effective projection of military power under international control to enforce international decisions against aggressors was supposed to distinguish the United Nations from the League of Nations. The onset of the Cold War made this impossible on a systematic basis. A new means of peace maintenance was necessary, one that would permit the world organization to act within carefully defined limits when the major powers agreed or at least acquiesced.

UN peacekeeping proved capable of navigating the turbulent waters of the Cold War through its neutral claims and limited range of activities. Again, global politics circumscribed UN activities. Although peacekeeping is not specifically mentioned in the Charter, it became the organization’s primary function in the domain of peace and security. The use of sizable troop contingents for this purpose is widely recognized as having begun during the 1956 crisis in Suez. Contemporary accounts credit Lester B. Pearson, then Canada’s secretary of state for external affairs and later prime minister, with proposing to the General Assembly that Secretary-General Hammarskjöld organize an “international police force that would step in until a political settlement could be reached.”3

Close to five hundred thousand military, police, and civilian personnel—distinguished from national soldiers by their trademark powder-blue helmets and berets—served in UN peacekeeping forces during the Cold War, and some seven hundred lost their lives in UN service during this period. Alfred Nobel hardly intended to honor soldiers when he created the peace prize that bears his name, and no military organization had received the prize throughout its eighty-seven-year history. This changed in December 1988, when UN peacekeepers received the prestigious award. This date serves as the turning point in the following discussion to distinguish UN security activities during and after the Cold War.

The Cold War and the Birth of Peacekeeping, 1948–1988

The lack of any specific reference to peacekeeping in the Charter led Hammarskjöld to coin the poetic and apt expression “Chapter six and a half,” which referred to stretching the original meaning of Chapter VI. And certainly peacekeeping “can rightly be called the invention of the United Nations,” as then secretary-general Boutros Boutros-Ghali claimed in An Agenda for Peace.4 The lack of a clear international constitutional basis makes a consensus definition of peacekeeping difficult, particularly because peacekeeping operations have been improvised in response to the specific requirements of individual conflicts. Despite the lack of consensus and the multiplicity of sources,5 former UN undersecretary-general Marrack Goulding provided a sensible definition of peacekeeping: “United Nations field operations in which international personnel, civilian and/or military, are deployed with the consent of the parties and under United Nations command to help control and resolve actual or potential international conflicts or internal conflicts which have a clear international dimension.”6

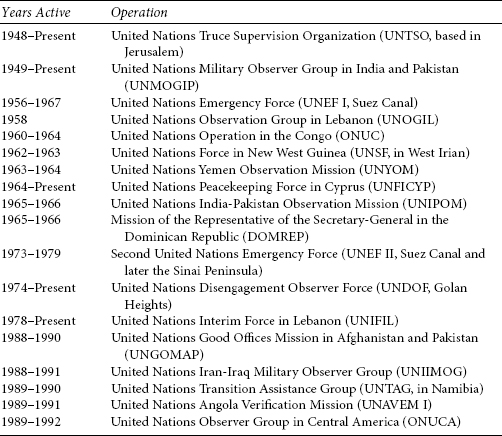

The first thirteen UN peacekeeping and military observer operations deployed during the Cold War are listed in Table 2.1.7 Five were still in the field in December 2012. From 1948 to 1988, peacekeepers typically served two functions: observing the peace (that is, monitoring and reporting on the maintenance of cease-fires) and keeping the peace (that is, providing an interpositional buffer between belligerents and establishing zones of disengagement). The forces were normally composed of troops from small or nonaligned states, with permanent members of the Security Council and other major powers making troop contributions only under exceptional circumstances. Lightly armed, these neutral troops were symbolically deployed between belligerents who had agreed to stop fighting; they rarely used force and then only in self-defense and as a last resort. Rather than being based on any military prowess, the influence of UN peacekeepers in this period resulted from the cooperation of belligerents mixed with the moral weight and diplomatic pressure of the international community of states.8

Peacekeeping operations essentially defended the status quo. They helped suspend a conflict and gain time so that belligerents could be brought closer to the negotiating table. However, these operations do not by themselves guarantee the successful pursuit of negotiations. They are often easier to institute than to dismantle, as the case of over four decades of this activity in Cyprus demonstrates. The termination of peacekeeping operations creates a vacuum and may have serious consequences for the stability of a region, as happened in 1967 at the outbreak of the Arab-Israeli War following the withdrawal of UNEF I at Egypt’s request.

The UN Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) represents a classic example of international compromise during the Cold War. This operation was designed as a microcosm of geopolitics, with a NATO member and a neutral on the pro-Western Israeli side of the line of separation, and a member of the Warsaw Pact and a neutral on the pro-Soviet Syrian side. UNDOF was established on May 31, 1974, upon the conclusion of disengagement agreements between Israel and Syria that called for an Israeli withdrawal from all areas it occupied within Syria, the establishment of a buffer zone to separate the Syrian and Israeli armies, and the creation of areas of restricted armaments on either side of the buffer zone. UNDOF was charged with verifying Israel’s withdrawal, establishing the buffer zones, and monitoring levels of militarization in the restricted zones.

TABLE 2.1 UN Peacekeeping Operations During the Cold War and During the Initial Thaw

Years Active |

Operation |

1948–Present |

United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO, based in Jerusalem) |

1949–Present |

United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) |

1956–1967 |

United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF I, Suez Canal) |

1958 |

United Nations Observation Group in Lebanon (UNOGIL) |

1960–1964 |

United Nations Operation in the Congo (ONUC) |

1962–1963 |

United Nations Force in New West Guinea (UNSF, in West Irian) |

1963–1964 |

United Nations Yemen Observation Mission (UNYOM) |

1964–Present |

United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) |

1965–1966 |

United Nations India-Pakistan Observation Mission (UNIPOM) |

1965–1966 |

Mission of the Representative of the Secretary-General in the Dominican Republic (DOMREP) |

1973–1979 |

Second United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF II, Suez Canal and later the Sinai Peninsula) |

1974–Present |

United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF, Golan Heights) |

1978–Present |

United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) |

1988–1990 |

United Nations Good Offices Mission in Afghanistan and Pakistan (UNGOMAP) |

1988–1991 |

United Nations Iran-Iraq Military Observer Group (UNIIMOG) |

1989–1990 |

United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG, in Namibia) |

1989–1991 |

United Nations Angola Verification Mission (UNAVEM I) |

1989–1992 |

United Nations Observer Group in Central America (ONUCA) |

UNDOF employed 1,250 armed soldiers, including 90 military observers. Troop deployment emphasized equal contributions by countries that were either politically neutral or sympathetic to the West or East. Originally, Peru, Canada, Poland, and Austria provided troops for the operation. Canadian and Peruvian forces operate along the Israeli side; Polish and Austrian troops operate in Syrian territory.

Despite the declared hostility between Israel and Syria, UNDOF has proven instrumental in maintaining peace in the Golan Heights. The size and weapons of the force clearly are inadequate to halt any serious incursions, but the two longtime foes want the force there. Thus, since 1977 no major incidents have occurred in areas under UNDOF’s jurisdiction. Success is attributable to several factors: the details of the operation were thoroughly defined before its implementation, leaving little room for disagreement; Israel and Syria cooperated with UNDOF; and the Security Council supported the operation fully.

Principles of Traditional Peacekeeping

The man who helped give operational meaning to “peacekeeping,” Brian Urquhart, has summarized the characteristics of UN operations—which can be gleaned inductively from the case of UNDOF—during the Cold War as follows: consent of the parties, continuing strong support of the Security Council, a clear and practicable mandate, nonuse of force except as a last resort and in self-defense, the willingness of troop contributors to furnish military forces, and the willingness of member states to make available requisite financing.9 Developing each of the characteristics serves as a bridge to our discussion of subsequent UN efforts that extend beyond traditional limitations because many of these traditional standard operating procedures would need to be set aside or seriously modified to confront the challenges of many post–Cold War peace operations.

Consent Is Imperative Before Operations Begin. In many ways, consent is the keystone of traditional peacekeeping, for two reasons. First, it helps to insulate the UN decision-making process against great-power dissent. For example, in Cyprus and Lebanon the Soviet Union’s desire to obstruct was overcome because the parties themselves had asked for UN help.

Second, consent greatly reduces the likelihood that peacekeepers will encounter resistance while carrying out their duties. Peacekeepers are physically in no position to challenge the authority of belligerents (either states or opposition groups), and so they assume a nonconfrontational stance toward local authorities. Traditional peacekeepers do not impinge on sovereignty. In fact, it is imperative to achieve consent before operations begin.

The emphasis that traditional missions place on consent does have drawbacks, as two observers have noted: “Peacekeeping forces cannot often create conditions for their own success.”10 For example, belligerents will normally consent to a peacekeeping mission once wartime goals have been achieved or losses have made belligerents war-weary. In instances where neither of these conditions has been met, it becomes necessary to find alternate ways to induce warring parties to achieve and maintain consent. Moreover, major powers need to pressure their clients not only to consent but also to negotiate. When political will is lacking, either wars continue unaddressed by the organization, or UN peacekeepers become inextricably tied down in conflict, neither able to bring peace to the area nor able to withdraw from it. For example, the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP), originally deployed in 1964 to separate warring Turkish and Greek Cypriot communities and then, given a new mandate in 1974, remains in the field because consent for deployment has not been matched by a willingness to negotiate the peace. Likewise, the United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP), established in 1949; UNDOF, created in 1974; and the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), deployed in 1978—all continue to operate because of the absence of political conditions allowing for their removal.

Peacekeeping Operations Need Full Support from the Security Council. Such support is necessary not only in the beginning stages of the mission, when decisions regarding budgets, troop allotments, and other strategic priorities are made, but also in its later stages, when mandates come up for renewal. The host of problems in the Congo illustrates the dangers of proceeding without the support of the major powers in the Security Council. Backing by both the United States and the Soviet Union of UNEF I in the General Assembly was the only case in which the United States and the Soviet Union abandoned the Security Council and then resorted to the General Assembly to get around a veto. A practice has developed for the Security Council to renew the mandate of missions several times—frequently semiannually for years on end—in order to keep pressure on parties who may be threatened with the possible withdrawal of peacekeepers. Full Security Council support also enhances the symbolic power of an operation.

Participating Nations Need to Provide Troops and to Accept Risks. Successful peacekeeping missions require the self-sustained presence of individual peacekeeping battalions, each of which is independent but also functions under UN command. Frequently they deploy in areas of heavy militarization. Mortal danger exists for peacekeepers. Governments that provide troops must be willing to accept the risks inherent in a given mission, and they also must be able to defend such expenditures and losses before their parliaments.

Permanent Members Do Not Normally Contribute Troops Except for Logistical Support. Providing logistical support has become a specialty of the United States, which during the Cold War essentially airlifted most start-up troops and provisions for UN operations. Keeping major powers from an active role in peacekeeping was imperative for the perceived neutrality that successful peacekeeping strives to attain. Washington and Moscow were thought to be especially tainted by the causes they supported worldwide.

The experience with exceptions to this rule has been mixed. Because of the special circumstances involved in Britain’s possession of extraterritorial bases on the island of Cyprus, the United Kingdom was involved in UN operations there from the outset; that effort has been worthwhile. The experience of French peacekeepers deployed in UNIFIL in Lebanon was a source of problems because of France’s perceived involvement as an ex-colonial power on the Christian side of the conflict. Consequently, French troops came under attack by local factions and were forced to withdraw from the zone of operations and to remain in the UN compound.

A Clear and Precise Mandate Is Desirable. The goals of the mission should be clear, obtainable, and known to all parties involved. Enunciation of the mission’s objectives reduces local suspicion. Yet a certain degree of flexibility is desirable so that the peacekeepers may adapt their operating strategies to better fit changing circumstances. The goals of the operation may be expanded or reduced as the situation warrants. In fact, diplomatic vagueness may at times be necessary in Security Council voting to secure support or to keep future options open.

Force Is Used Only in Self-Defense and as a Last Resort. Peacekeepers derive their influence from the diplomatic support of the international community, and therefore they use force only as a last resort and in self-defense. The Peacekeeper’s Handbook states this wisdom: “The degree of force [used] must only be sufficient to achieve the mission on hand and to prevent, as far as possible, loss of human life and/or serious injury. Force should not be initiated, except possibly after continuous harassment when it becomes necessary to restore a situation so that the United Nations can fulfill its responsibilities.”11

Peacekeeping techniques differ greatly from those taught to most soldiers and officers by their national training authorities. In the past only the Scandinavian states and Canada have trained large numbers of their recruits and officers specifically for peacekeeping. Soldiers from other countries have often found themselves unprepared because the prohibition against the use of force contradicts their standard military training. Thus, the administrative, technological, and strategic structures that sustain peacekeeping have reflected the need for professional diplomatic and political expertise more than the need for professional soldiers.

“CHAPTER SIX AND A HALF” ON HOLD, 1978–1988

From 1948 to 1978 thirteen UN peacekeeping operations took place. In the ten years after 1978, however, no new operations materialized, even as a rash of regional conflicts involving the superpowers or their proxies sprang up around the globe.12

The last operation approved before the decade-long hiatus highlights the difficulties the UN encountered during this period. UNIFIL in Lebanon was beset with problems similar to those experienced in the Congo during the 1960s, where domestic conflict and an absence of government structures had given the world organization an operational black eye.13 UNIFIL’s difficulties illustrate the dangers inherent in operations that lack both clear mandates and the effective cooperation of belligerents and that exist amidst political chaos and great-power disagreement.

UNIFIL was established at the Security Council’s request on March 19, 1978, following Israel’s military incursion into southern Lebanon. Israel claimed that military raids and shelling by members of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) who were based in southern Lebanon threatened Israeli peace and security. Israel’s response embarrassed its primary ally, the United States. Washington used its influence in the Security Council to create UNIFIL as a face-saving means for Israel to withdraw when criticism of its tactics became widespread. The operation’s duties included confirming the Israeli withdrawal; establishing and maintaining an area of operations; preventing renewed fighting among the PLO, Israel, and the Israeli-backed Southern Lebanese Army; and restoring Lebanese sovereignty over southern Lebanon.

At UNIFIL’s maximum strength, over seven thousand soldiers were deployed, including contingents from Canada, Fiji, France, Ghana, Iran, Ireland, Nepal, the Netherlands, Nigeria, Norway, and Senegal. UNIFIL encountered significant problems as a result of the conflicting interests of the major parties involved in southern Lebanon. Israel refused to cede control of the South to UNIFIL, choosing instead to rely on the Southern Lebanese Army, which resisted UNIFIL’s efforts to gain control in the area. The PLO demanded that it be allowed to operate freely in the South to continue its resistance against Israel. The Lebanese government insisted that UNIFIL assume control of the entire region. Consequently, UNIFIL found itself sandwiched between the PLO and the Southern Lebanese Army and routinely came under fire. In 1982, as Israel reinvaded Lebanon and marched to Beirut, UNIFIL stood by, powerless, in the face of Israel’s superior firepower and the unwillingness of troop contributors or the UN membership to resist. UNIFIL’s refusal to stand its ground echoed Egypt’s 1967 request to withdraw UNEF I; once UN troops were pulled out, war ensued.

The lack of political will among the regional participants and troop contributors was matched by the incapacity of the Lebanese government’s army and police. Yet UNIFIL became part of the local infrastructure,14 and its withdrawal would be disruptive.

Much of the impetus for the increased tension between East and West and for the end of new UN deployments came from the United States after the Reagan administration assumed power in 1981. Elected on a platform of anticommunism, the rebuilding of the national defense system, and fiscal conservatism, the administration was determined to roll back Soviet gains in the Third World. Neoconservatives in Washington scorned the world organization and cast it aside as a bastion of Third World nationalism and support for communism. The UN’s peacekeeping operations were tarred with the same brush. The Reagan administration also refused to pay its assessed dues (including a portion of the assessment for UNIFIL, which Washington had originally insisted on).15 The organization was in near bankruptcy at the same time that U.S. respect for international law seemed to evaporate and unilateral action gained favor.16 Intervening in Grenada, bombing Libya, and supporting insurgencies in Nicaragua, Angola, Afghanistan, and Cambodia attested to U.S. preferences in the 1980s. The Soviet Union countered these initiatives. Central America, the Horn of Africa, much of southern Africa, and parts of Asia became battlegrounds and flash points for the superpowers or their proxies.

Short of sending international forces, a group of states may attempt to isolate an aggressor by cutting off diplomatic or economic relations with a view toward altering offensive behavior. These are coercive, albeit nonforcible, actions—the first step in Chapter VII’s enforcement progression. Diplomatic and economic sanctions are significantly more emphatic than the political influence that makes up the everyday stuff of foreign policy, even if less emphatic than the dispatch of troops.

On a spectrum ranging from political influence to outside military intervention, economic sanctions are enforcement measures that fall far short of military force. For the same reasons that real collective security was not possible during the Cold War, these milder forms of enforcement were also largely underused. The exceptions were against two pariahs, Rhodesia and South Africa, whose domestic racist policies were widely condemned. As a reaction to Rhodesia’s unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) from the United Kingdom in 1965, the Security Council in 1966 ordered limited economic sanctions under Chapter VII of the Charter for the first time in UN history.17 Whether the trigger was due more to the UDI or to the human rights situation for Africans is debatable, but the result was that the council characterized the domestic situation as a “threat to the peace.” The council toughened the stance against the white-minority government by banning all exports and imports (except for some foodstuffs, educational materials, and medicines). These sanctions became “comprehensive” in 1968.

The sanctions initially extracted costs from the government of Rhodesian prime minister Ian Smith. But, ironically, they eventually helped immunize the country against outside pressure because they prompted a successful program of import substitution and the diversification of its economy. Although most members of the UN complied, some of those who counted did not. The United States, for example, openly violated sanctions after the Byrd amendment by Congress allowed trade with Rhodesia, even though the United States had voted for sanctions in the Security Council. According to U.S. judicial doctrine, if Congress uses its statutory authority to violate international law intentionally, domestic courts will defer to congressional action in U.S. jurisdiction. Many private firms as well as some other African countries also traded with Rhodesia, including the neighboring countries of Mozambique (a Portuguese colony) and the Republic of South Africa.

Although the Security Council authorized a forceful blockade to interrupt supplies of oil and the British navy did halt a few tankers, there was insufficient political will to effectively blockade the ports and coastlines of Mozambique and South Africa. Hence, the Security Council helped but can hardly be credited with the establishment of an independent Zimbabwe in 1979. The UN’s use of economic sanctions in this case was more important as legal and diplomatic precedent than as effective power on the ground.

UN-imposed sanctions against South Africa reflected the judgment that racial separation (apartheid) within the country was a threat to international peace and security. Limited economic sanctions, an embargo on arms sales, boycotts against athletic teams, and selective divestment were all part of a visible campaign to isolate South Africa. These acts exerted pressure, but it is difficult to quantify their impact. Initially, South Africa’s high-cost industry thrived by trying to replace missing imports (as had Rhodesia’s), and it even managed to produce a variety of sophisticated arms that eventually became a major export. The transition to democracy (and the end of white rule) probably resulted more from the dynamics of the internal struggle by the black majority and the end of the Cold War than from sanctions. No doubt sanctions contributed to altering the domestic balance by demonstrating the risks and the costs of being isolated, but measuring their precise impact requires greater empirical work.

The Rhodesian and South African experiences show how the UN, through the Security Council, can link the domestic policies of states to threats to international peace and security and thereby justify Chapter VII action. Earlier, we pointed out the power of self-definition, and thus the council expanded the definition of a threat by the use of sanctions as enforcement tools for a domestic issue and thereby set an important precedent. UN sanctions are analytically distinct from bilateral economic sanctions or those imposed by treaty (for example, the Montreal Protocol to protect the ozone). The UN Charter never uses the word “sanctions” in Chapter VII, but Article 41 speaks of “measures not involving the use of armed force,” which “are to be employed to give effect to its decisions.” The continued use of partial or comprehensive sanctions has come under increased criticism because of their impact on vulnerable populations within targeted countries, a subject to which we return at the end of Chapter 3.

1. Leon Gordenker, The UN Secretary-General and the Maintenance of Peace (New York: Columbia University Press, 1967); and Leland M. Goodrich, Korea: A Study of U.S. Policy (New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 1956).

2. The tradition of acronyms in English was set aside as operations in Spanish-speaking and French-speaking countries became more widespread.

3. Max Harrelson, Fires All Around the Horizon: The UN’s Uphill Battle to Preserve the Peace (New York: Praeger, 1989), 89.

4. Boutros Boutros-Ghali, An Agenda for Peace: Preventive Diplomacy, Peacemaking, and Peace-Keeping: Report of the Secretary-General Pursuant to the Statement Adopted by the Summit Meeting of the Security Council on 31 January 1992 (New York: United Nations, 1992), para. 46.

5. United Nations, The Blue Helmets: A Review of United Nations Peace-Keeping, 2nd ed. (New York: UNDPI, 1990), 4; Alan James, Peacekeeping in International Politics (London: Macmillan, 1990), 1; and Boutros-Ghali, Agenda, para. 20.

6. Marrack Goulding, “The Changing Role of the United Nations in Conflict Resolution and Peace-Keeping,” speech given at the Singapore Institute of Policy Studies, March 13, 1991, 9. See also his “The Evolution of Peacekeeping,” International Affairs 69, no. 3 (1993): 451–464, and Peacemonger (London: John Murray, 2002).

7. Thomas G. Weiss and Jarat Chopra, Peacekeeping: An ACUNS Teaching Text (Hanover, N.H.: Academic Council on the United Nations System, 1992), 1–20. The United Nations published its own volume, The Blue Helmets, in 1985, which was revised in 1990 and 1996. Updates are now on the United Nations website at www.un.org. See also Rosalyn Higgins, United Nations Peacekeeping: Documents and Commentary, vols. 1–4 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969–1981).

8. John Mackinlay, The Peacekeepers: An Assessment of Peacekeeping Operations at the Arab-Israel Interface (London: Unwin Hyman, 1989); Augustus Richard Norton and Thomas G. Weiss, UN Peacekeepers: Soldiers with a Difference (New York: Foreign Policy Association, 1990); William J. Durch, ed., The Evolution of UN Peacekeeping (New York: St. Martin’s, 1993); Paul F. Diehl, International Peacekeeping (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993); and Adekeye Adebajo, UN Peacekeeping in Africa: From the Suez Crisis to the Sudan Conflicts (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 2011).

9. Brian Urquhart, “Beyond the ‘Sheriff’s Posse,’” Survival 32, no. 3 (1990): 198, and A Life in Peace and War (New York: Harper and Row, 1987).

10. John Mackinlay and Jarat Chopra, “Second Generation Multinational Operations,” Washington Quarterly 15, no. 3 (1992): 114.

11. International Peace Academy, Peacekeeper’s Handbook (New York: Pergamon, 1984), 56.

12. S. Neil MacFarlane, Superpower Rivalry and Third World Radicalism: The Idea of National Liberation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985); Elizabeth Kridl Valkenier, The Soviet Union and the Third World: An Economic Bind (New York: Praeger, 1983); and Jerry F. Hough, The Struggle for the Third World: Soviet Debates and American Options (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1986).

13. Bjorn Skogmo, UNIFIL: International Peacekeeping in Lebanon (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 1989); and Emmanuel A. Erskine, Mission with UNIFIL: An African Soldier’s Reflections (New York: St. Martin’s, 1989).

14. Marianne Heiberg, “Peacekeepers and Local Populations: Some Comments on UNIFIL,” in The United Nations and Peacekeeping: Results, Limitations, and Prospects: The Lessons of 40 Years of Experience, ed. Indar Jit Rikhye and Kjell Skjelsback (London: Macmillan, 1990), 147–169.

15. Jeffrey Harrod and Nico Shrijver, eds., The UN Under Attack (Aldershot, U.K.: Gower, 1988).

16. David P. Forsythe, The Politics of International Law: U.S. Foreign Policy Reconsidered (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 1990).

17. Henry Wiseman and Alistair M. Taylor, From Rhodesia to Zimbabwe: The Politics of Transition (New York: Pergamon, 1981); and Stephen John Stedman, Peacemaking in Civil War: International Mediation in Zimbabwe, 1974–1980 (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 1991).