1.

On December 27, 1954, Günther Quandt traveled to Egypt for a holiday. Since his denazification trials concluded he was working harder than ever, laboring away in a nondescript office in Frankfurt to restructure what remained of his business empire. But his health was frail. He had rapidly recovered from a minor stroke in 1950, but he still had to check in at a hospital every three to six months for a few weeks to address various other health issues. Günther always arrived at the hospital with a suitcase full of work documents. Now he wanted to flee Germany’s brutal winter and spend a couple of weeks down in Africa. For this post-Christmas holiday, the traveler had assembled an itinerary that included a sightseeing trip to the pyramids at Giza, on the outskirts of Cairo. He stayed at the capital’s famed luxury hotel, Mena House. But he never made it to the pyramids. On the morning of December 30, 1954, Günther died in his hotel suite, with its views of the Sphinx. Whether he died alone remains a mystery. It was long rumored that the mogul succumbed following “a little death.” Günther was seventy-three years old.

The mood in West Germany had changed earlier that year. German pride was back. After the country beat Hungary in the 1954 World Cup soccer final, the Nazi era chant “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles” (“Germany, Germany above all”) rang through the stadium in Bern. Germany was back, but Günther was gone.

The 1950s were more than just a new decade. They were the dawn of a new German era, all of it thanks to the US government. The outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950 was the spark that ignited West Germany’s economic resurgence. As the Truman administration began spending billions on rearmament, it turned many American factories over to the manufacture of weapons. As a result, production of many other goods bottlenecked, and scarcities spiked. West Germany stepped in to pick up the slack. A key Western industrialized nation, it was able to fill that manufacturing vacuum and likewise could handle the massive global demand in consumer goods by means of its export prowess. By 1953, West Germany’s economy had quadrupled. Any lingering aversion to buying German products clearly and quickly vanished from other countries.

In the new federal republic of West Germany, led by Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, the Wirtschaftswunder, or economic miracle, heralded an age of unprecedented economic growth and massive prosperity for most Germans. In particular, those “denazified” tycoons and their heirs in the West entered an epoch of unfathomable global wealth, which persists to this day. But this newfound windfall entirely bypassed the millions living in the Soviet-led Communist state of East Germany. And as that inequity festered, a culture of silence also permeated the divided Germany. It buried the horrors of the Third Reich and the diabolical roles that many Germans had played in it. As West Germany’s moguls turned their tens or hundreds of millions of reichsmarks into billions of deutsch marks and dollars, and (re)gained control of swaths of the German and global economy, they rarely, if ever, looked back. These tycoons left their heirs with firms and fortunes worth billions — but also with a bloodstained history waiting to be uncovered.

2.

On January 8, 1955, a memorial service was held for Günther Quandt in the assembly hall of Frankfurt’s Goethe University. Hermann Josef Abs — one of the Third Reich’s most influential bankers, who was now rapidly becoming West Germany’s most powerful financier as the chairman of Deutsche Bank — had this to say of Günther in his eulogy: “He never submitted servilely to the overbearing state.” It was the exact opposite of what Abs had said about Günther during the mogul’s lavish sixtieth-birthday bash in Berlin, in 1941. Back then, speaking to the Nazi elite, the banker had lauded Günther’s servility: “But your most outstanding characteristic is your faith in Germany and the Führer.”

Horst Pavel, Günther’s closest aide and a key architect of AFA’s Aryanization strategy, also delivered a eulogy, which barely mentioned the Nazi era, except to say how extremely hard his boss and mentor had worked during the war. Instead, Pavel spoke admiringly about Günther’s “brilliant” ability to capitalize on Germany’s many financial and political disasters: “He … prepared his actions carefully and then operated as skillfully as he did tenaciously until the set goal was ultimately achieved.”

Although the Soviet authorities had expropriated Günther’s firms, factories, houses, and estate in East Germany, he still retained many assets in West Germany: the AFA battery factory in Hannover, several DWM weapons plants plus its subsidiaries Mauser and Dürener, and what remained of Byk Gulden, a massive chemicals and pharmaceuticals firm that had already been Aryanized when Günther bought it during the war, to name just a few. He also had an almost one-third stake in the oil and potash giant Wintershall left and a 4 percent interest in Daimler-Benz; until 1945, he had served as a supervisory board member of the Stuttgart-based car giant. It was a prescient move. Mass motorization was growing around the world, and West Germany’s economic future lay with the auto industry. In the years before his death, Günther restructured AFA, positioning it as key supplier of accumulators and starter batteries for cars.

Restructuring in West Germany meant reckoning with some ugly truths. DWM’s full name — Deutsche Waffen- und Munitionsfabriken — was changed to something that sounded more innocuous: IWK (for Industriewerke Karlsruhe). Plus, the firm was barred from making weapons and ammo, for now anyway. Günther’s Byk Gulden had grown into one of Germany’s largest pharmaceuticals businesses by the end of the war, but it partly consisted of Aryanized subsidiaries. After the war, heirs of the original Jewish owners initiated restitution proceedings. These negotiations were discreetly concluded, and land, buildings, and machinery were turned over to the heirs. Günther’s attorney approached these matters pragmatically: “There wasn’t a single German company that did not conduct Aryanizations during the war, so there were restitution proceedings here and there, and lawyers were needed for this,” he later recalled.

Günther had fought these proceedings tooth and nail where he could. In 1947, Fritz Eisner, a German Jewish chemist who had fled to London, filed a restitution claim against AFA in the British occupation zone. Günther had Aryanized Eisner’s electrochemical companies outside Berlin in 1937, and now Eisner wanted to be compensated to make up for Günther’s pittance of a payment to him. But the firms now lay in the Soviet occupation zone and had been expropriated. Instead of apologizing to Eisner for extorting and underpaying him, Günther had AFA’s lawyers fight the claim on jurisdictional grounds. Eisner’s restitution claim was rejected in 1955, not long after Günther died.

3.

What was Günther Quandt’s business legacy, exactly? Kurt Pritzkoleit, a business journalist who documented German industrialists, gave this title to a book chapter on Quandt in 1953: “The power of the great unknown.” Pritzkoleit was the first reporter to expose the sheer size of Günther’s industrial empire and his penchant for secrecy:

Quandt developed the talent of shielding his work from the view of the outsider into a skill that is rarely found … hardly anyone has been able to fully grasp the scope and universality of his activities, apart from those close to him. His mimicry, the ability, so rare among us weak and vain people, to take on the protective color of the surroundings, is developed to perfection: Among textile manufacturers he appears as a textile manufacturer, among metalworkers as a metalworker, among weapons specialists as a weapons specialist, among electrical engineers as an electrical engineer, among insurance experts as an insurance expert, among potash miners as a potash miner, and in every manifestation he appears so genuine and convincing that the observer who encounters him in an area of his multifaceted activity believes the protective color to be the original and only one, innate and unchangeable.

Dynastic and entrepreneurial continuity had been crucial to Günther. The mogul had seen other business families fall prey to infighting related to succession. He wanted to avoid that at all costs, so he meticulously laid out plans for after his death. His sons, Herbert and Harald, were each to take over a specific part of his industrial empire. Harald was the more technically gifted of the two. He had graduated as a mechanical engineer in 1953 and as a student had already served on numerous supervisory boards at his father’s firms. Therefore it made sense for him to oversee the weapons and machinery firms IWK, Mauser, Busch-Jaeger Dürener, and Kuka. Harald’s decade-older half brother, Herbert, would supervise AFA plus the Wintershall and Daimler-Benz stakes.

Günther left behind a fortune of 55.5 million deutsch marks (about $135 million today), mostly consisting of company shares. He left them to Herbert and Harald in almost equal parts through two holding companies. But since Günther had already transferred many assets to his two sons over the previous decade — a strategy to avoid inheritance tax, which many of the world’s wealthiest still exploit today — the actual size of his estate was impossible to calculate. Suffice it to say, it was larger than 55.5 million deutsch marks. The Quandts’ constructions of ownership and debt through various holding companies were so complex that even the most experienced auditors gave up. “To what extent the securities were acquired with personal funds or with bank loans cannot be specified in detail … These transactions … are so interwoven that it is impossible to establish a connection between purchases of securities and individual borrowings,” read a German government-ordered review from 1962.

Nonetheless, the business transitioned smoothly to the next generation of Quandts. Günther’s son Herbert later quipped: “With all due reverence for my father: If his death hadn’t been in the newspaper, no one would have noticed it businesswise.” Work at the Quandt factories was suspended in tribute during Günther’s memorial service. But in no time at all, it was back to business. Herbert and Harald lived three hundred feet apart from each other in Bad Homburg, a spa town north of Frankfurt. They were keen on expanding the Quandt business empire and leaving their own legacy. Directly after their father’s death, the half brothers began to increase a share package they had inherited in Daimler-Benz, the manufacturer of Mercedes. But unbeknownst to them, another German mogul, with even more money at his disposal, had investment plans of his own and spare millions to execute them. That mogul was Friedrich Flick. He too had his sights set on Germany’s largest car firm. “The battle for Daimler” was about to erupt.

4.

In mid-July 1955, at Daimler-Benz’s annual meeting in Stuttgart, two new major shareholders registered and were elected to the carmaker’s supervisory board: Herbert Quandt and Friedrich Flick. Herbert registered a sizable 3.85 percent stake in Daimler, which he and Harald had inherited from Günther. But Flick took everyone by surprise by filing a 25 percent interest, a blocking minority. The mogul, fresh out of prison, had secretly started buying shares in Daimler. The Quandt siblings and Flick now wanted more. Herbert and Harald desired a 25 percent interest. Flick was eyeing majority control. As two of Germany’s wealthiest business dynasties went head to head to increase their stakes, Daimler’s share price rose feverishly. In January 1956, a third investor emerged: a speculating timber merchant from Bremen who had amassed an 8 percent stake. He wanted to sell his share package to one of the two parties at a massive premium: double the stock price.

United by the presence of a common enemy, the Quandts and Flick now called a truce. They made a secret deal to squeeze out the new investor. Flick rejected the speculator’s offer, which forced the latter to sell the stake to Herbert and Harald at a much lower price. The Quandt siblings and Flick then split the share package and continued to increase their stakes. At Daimler’s next annual general meeting in June 1956, Harald Quandt and Flick’s elder son Otto-Ernst joined the supervisory board of the Stuttgart carmaker.

By late 1959, Flick was Daimler-Benz’s largest shareholder, with about a 40 percent stake. The Quandts held some 15 percent. Between them stood Deutsche Bank, with a 28.5 percent interest. The triumvirate of Hermann Josef Abs — Deutsche Bank’s chairman and Daimler-Benz’s supervisory board chairman — the Flicks, and the Quandts would rule over Europe’s largest carmaker for the next decades. And it was hardly a contentious reign. Flick placed part of his Daimler stake in a holding firm owned by Herbert Quandt, which allowed Herbert to qualify for a tax break. The dynasties were now officially in cahoots.

But whereas Herbert and Flick wound up closely collaborating at Daimler, in an attempt to rescue BMW they found themselves on opposing sides. The Munich carmaker was on the brink of bankruptcy in the late 1950s, due to a lack of variety in car models and bad management. Herbert asked Harald’s permission to buy BMW shares on his own account, separate from the Quandt group. It was a risky investment, but Herbert, who loved fast cars, wanted a shot at restructuring the firm.

Herbert began buying BMW shares and convertible bonds. The press first suspected that Flick was behind the rising share price, but he denied it. However, at BMW’s annual meeting in December 1959, a Flick-backed restructuring plan was proposed. It included issuing new shares exclusively to Daimler-Benz, which then would have held a majority stake in its competitor. Flick, as Daimler’s largest shareholder, saw it as a cheap way of bringing BMW under his control. But the restructuring plan that Flick supported ultimately was not accepted at the shareholders’ meeting in Munich, which was quite heated. Following Flick’s attempted corporate coup, Herbert firmly took the reins and began to reorganize BMW himself, after becoming its largest shareholder.

Herbert’s decade-long restructuring of BMW proved successful. He installed new management, expanded the range of car models, and continued buying shares. In 1968, BMW hit one billion deutsch marks in revenue, and Herbert held 40 percent of its stock. That summer, he sold the family’s longtime stake in the oil and gas giant Wintershall to the chemicals behemoth BASF for about 125 million deutsch marks. He used part of the proceeds to become BMW’s controlling shareholder. To this day, two of his children still retain that level of control over the carmaker, making them Germany’s wealthiest siblings.

5.

For the Quandts and many other German business dynasties, the ghosts of the Third Reich were never far off. This was mainly because the moguls themselves kept inviting them back. Harald Quandt hired a couple to join his household staff in Bad Homburg; each had worked for the Goebbelses during the Nazi era. “The same man who had chauffeured his mother in the 1930s now drove his daughters to school by car,” a biographer of the Quandt dynasty later revealed. Such hires weren’t limited to Harald’s private life, though. In the early 1950s, Harald brought two of Joseph Goebbels’s closest aides from the Ministry of Propaganda into the Quandt group, assigning them to high-ranking positions. The most prominent was Werner Naumann, Goebbels’s appointed successor in Hitler’s political testament. Naumann had been yet another lover of Harald’s mother, Magda. When Harald hired him as a member of the board of directors at Busch-Jaeger Dürener, Naumann had just recently been released by the British authorities in Germany; in 1953 Naumann and a group of neo-Nazis had attempted to infiltrate a German political party, but the British had thwarted the plot. Apparently this didn’t bother the Quandt heir. Speaking to a friend, Harald defended his decision to hire Naumann, deeming him “a clever fellow and not a Nazi.” But Naumann had joined the NSDAP in 1928 and was appointed SS brigadier general in 1933. He was a committed Nazi by any measure.

And Harald wasn’t alone in maintaining ties to Germany’s dark past as he amassed dynastic wealth. The two former SS officers Ferry Porsche and Albert Prinzing were busy making the Porsche 356 an enormous global success during the 1950s. Ferry surrounded himself with yet more former SS officers at the Porsche company in Stuttgart. In 1952, he put Baron Fritz Huschke von Hanstein in charge of Porsche’s global public relations and made him the director of its auto-racing team. Von Hanstein had been a wartime racing icon, driving Himmler’s favorite BMW while wearing overalls embellished with the initials SS— which he dryly explained stood for “Super-Sport.” Von Hanstein’s career in the SS wasn’t limited to racing. As an SS captain, he assisted with the “resettlement” of Jews and Poles in Nazi-occupied Poland. But von Hanstein fell out of favor with Himmler after he was reprimanded by an SS court for attempted rape.

In January 1957, Porsche hired Joachim Peiper, who had been released from Landsberg Prison just four weeks earlier, when a US-German clemency committee commuted his death sentence. Peiper, a former adjutant to Himmler, had been sentenced by a US military court in Germany after the war for having commanded the SS tank unit responsible for the Malmedy massacre in 1944, in which eighty-four American prisoners of war were murdered. At Albert Prinzing’s prompting, Porsche hired the Nazi war criminal as its head of sales promotion. Peiper was all too pleased with his new position. “You see … I silently swim in the big slimy floods of the Federal Republic’s economic wonder. Not at the top, but also not at the bottom. In the middle, without making any waves,” Peiper wrote to his lawyer. But in the end, Peiper’s employment at the car company rocked the boat a little too much, even for a firm so well stocked with former SS officers (Hitler’s former chauffeur Erich Kempka and the SS general Franz Six were other recent hires). In 1960, Porsche concluded that his ongoing employment could potentially harm the firm’s reputation in the country most important to its export business: the United States. Peiper was fired.

In the same period, yet another former SS officer, Rudolf-August Oetker, was massively profiting from West Germany’s economic miracle. His family firm, Dr. Oetker, hit a new sales record in 1950, selling about 1.25 billion packages of baking powder and pudding mixes. With those profits, Rudolf-August turned his Bielefeld-based baking goods business into a worldwide conglomerate. He increased his family’s stake in the shipping firm Hamburg Süd and invested in more beer breweries. Rudolf-August also entered new industries: he bought the private bank Lampe and appointed the Nazi banker Hugo Ratzmann as its general partner. During the Third Reich, Ratzmann had helped Günther Quandt, Friedrich Flick, August von Finck, and many other tycoons conduct Aryanizations and expropriations in Germany and Nazi-occupied Poland.

Four years after Ratzmann died, in a 1960 car accident, Rudolf-August appointed Rudolf von Ribbentrop as a managing director at Lampe. He was the eldest son of Nazi Germany’s social-climber foreign minister, the first man to be hanged at Nuremberg’s gallows. Rudolf-August and Rudolf von Ribbentrop had been friends since 1940, but von Ribbentrop’s career in the SS had been far more successful than that of the pudding prince. Von Ribbentrop served as a highly decorated tank commander in the elite First Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler. His mother was an heiress to Henkell, one of Germany’s largest producers of sparkling wine. She had nominated her son as managing partner of Henkell after he was released as a prisoner of war, but her relatives and Henkell’s chairman, Hermann Josef Abs, blocked the appointment. They thought that the Ribbentrop name would be bad for business. But Rudolf-August had no such qualms. He “convinced me to stay away from the family clique and go to work for him,” von Ribbentrop later wrote in his memoir. “The business opportunity he made available to me constituted a greater challenge for me than I could have imagined. I shall ever be grateful to him.”

Rudolf-August first gave von Ribbentrop a job at a hand puppet factory he had invested in. Meanwhile, von Ribbentrop reinforced ties to his Waffen-SS network. In January 1957, he asked Rudolf-August to provide financial aid for veterans of his SS tank division who had been sentenced for the Malmedy massacre and had recently been released from prison. This group of Nazi war criminals included the SS unit’s former commanding officer and recent Porsche hire, Joachim Peiper. It was a small world after all. Rudolf-August was happy to financially support these old SS comrades, but the miserly magnate wanted to avoid direct payments; those weren’t tax deductible. Instead, Rudolf-August suggested using the Dr. Oetker conglomerate, as had been done before, he intimated, to channel money to Stille Hilfe (Silent Help), the secretive relief organization for convicted and fugitive members of the SS; it still exists today.

Rudolf-August soon promoted von Ribbentrop to general partner of Lampe bank. But the former SS comrades’ ties truly came full circle when Rudolf-August bought the Henkell family’s sparkling wine business for 130 million deutsch marks in 1986.

6.

One of the tycoons did face actual business repercussions because of his actions during the Third Reich, and he responded radically. In November 1954, Baron August von Finck was at the foot of the Alps, planning his revenge. The chief hunter he employed, a man named Bock, had put snow chains on the old jeep sitting in Bavaria’s Mittenwald village, on the border with Austria. Accompanied by his servant, his cook, and his hunting dog, Dingo, von Finck drove the breakneck roads up to the Vereinsalm, his rustic mountain cabin, which was decorated with antlers. He wanted to catch his breath in the snowy solitude below the Karwendel mountain range. He had just weathered the first exchange of blows in his power struggle with two of the world’s largest insurers.

Already back at the helm of his private bank, Merck Finck, for some time now, the fifty-six-year-old aristocratic financier was staging a hostile takeover of Allianz and Munich Re, the insurance giants cofounded by his father. The reason behind von Finck’s attempt at such a drastic coup: a recent demotion. In 1945, the American occupation authorities had removed the baron from his role as supervisory board chairman at both insurers; he had, however, been allowed to return as a supervisory board member, but not chairman, at Munich Re soon after his denazification trial ended. This wasn’t enough for von Finck. He wanted both his old positions back. Given von Finck’s recent history as a staunch supporter of Hitler and a major profiteer of private bank Aryanizations, it was inconceivable that the two renowned global insurers would let him return as chairman. So he angrily quit the board of Munich Re. “The year 1945 threw so much tradition overboard, and the new men at Allianz wanted their own circle. At that time, after all, the American tanks were rattling through the country, and heads had to roll,” von Finck, ensconced in his cabin, complained to a reporter from Der Spiegel.

Through his father’s inheritance and private bank, von Finck was still the largest shareholder at both insurers, whose share capital was closely intertwined. So, in response to the snub, the financier began secretly buying up Allianz shares via straw men over the course of 1954. He aimed to increase his 8 percent stake to at least a 25 percent blocking minority in order to gain control of both companies. Von Finck received no support for his hostile bid from Germany’s commercial banks, which had close ties to the insurers. But Bavaria’s wealthiest man had plenty of money to spend on his own. In an exceptionally uncharacteristic move, the frugal financier went so far as to buy 16.5 percent of all Allianz stock. However, the insurer blocked the registration of his new shares, so he couldn’t leverage his full voting rights. Meanwhile, the aloof baron, never one for the common man, failed to convince enough smaller shareholders to join his side and form a blocking minority.

A solution had to be found. After dogged negotiations, von Finck and the insurers reached an agreement in late January 1955. In exchange for getting his new shares registered, von Finck withdrew his plan to put proposals related to restructuring to a vote at an extraordinary shareholders’ meeting he had called. But the financier still remained a major shareholder of the two insurers; he could still be a massive headache for them down the line. More negotiations followed, and the insurers struck a different deal with their former chairman. In exchange for a large part of his Allianz and Munich Re shares, von Finck would receive a considerable minority stake in a major steel firm, Südwestfalen.

To von Finck’s great dismay, he soon had to contend with a new majority shareholder at Südwestfalen. It was none other than the baron’s longtime acquaintance Friedrich Flick. The mogul was wheeling and dealing everywhere in the 1950s, making up for lost time and business after his stint in prison. The Düsseldorf-based Flick conglomerate had almost entirely said farewell to coal, was ramping up its investments in steel, and venturing into the automobile and chemical industries. At the same time, another trade that was all too familiar to the mogul was having a renaissance in West Germany: weapons manufacturing. Flick wanted in, and he wasn’t the only one. There were lucrative defense contracts to be won, and plenty of tycoons eyeing them. Germany’s arms race was on again.

7.

Harald Quandt, the former paratrooper lieutenant in the Luftwaffe, was in charge of the arms and ammunition branch of the family’s sprawling business empire. He was the head of IWK — formerly known as DWM — which was making a quick comeback as one of West Germany’s largest weapons manufacturers. The country owed its rearmament to America’s involvement in the Korean War and the Cold War. After the Korean War ended, the Eisenhower administration demanded that its Western allies take up a more equal share of the military burden related to the Cold War. Chancellor Adenauer seized on this as an opportunity to argue for the rearmament of West Germany. In May 1955, the country joined NATO and was allowed to have an army again. Six months later, West Germany established its new military, the Bundeswehr. Soon after, the Quandts’ IWK and its rifle-making subsidiary, Mauser, were permitted to manufacture weapons again.

The decision to rearm was grist to the mill for a technology geek like Harald. He had a fully automatic shooting range installed in his basement; a radiation-proof bunker was built beneath a Quandt family villa in Bad Homburg. In 1957, the engineering graduate even got the opportunity to develop the prototype for a tank. The French and West German armies had agreed on producing one together and issued a design competition. A consortium led by Harald’s IWK won. But the Franco-German tank project eventually fell through. West Germany withdrew from it because the government wanted the country to build its own tank: the Leopard.

West Germany ordered a massive number of the new battle tank. The West German army wanted between a thousand and fifteen hundred Leopard tanks, built at a unit price of 1.2 million deutsch marks; this first order could go as high as 1.8 billion deutsch marks. Harald felt confident that he would win this contract, but he faced stiff competition from two tycoons with far more experience in building and designing tanks: Friedrich Flick and Ferry Porsche. Although Flick’s right-hand man declared to the press in 1956 that the convicted weapons producer “has a deep aversion to any kind of armament,” he reentered the business that same year. One of Flick’s steel subsidiaries started building aircraft parts for the new Luftwaffe’s Noratlas military transport plane, the Fiat G91 jet fighter, and the Lockheed F-104 fighter-bomber.

This was just the beginning of Flick’s weapon-production plans. When the orders for locomotives dried up at Krauss-Maffei, which Flick controlled, he had the company enter arms production through the Leopard tank tender, teaming up with Daimler-Benz for the engine and with Porsche for the design. But the Stuttgart auto firm was missing two of its cofounders. Ferdinand Porsche had died at seventy-five in 1951, followed the next year by Anton Piëch, who died unexpectedly at fifty-seven from a heart attack. The two men had never fully recovered from their detention in a French military prison.

Ferry Porsche and his sister, Louise Piëch, stepped in to fortify their respective Porsche companies. After having constructed the first car bearing the family name, Ferry now once again succeeded where his father had failed: sending off the prototype of a Porsche tank for wide production. In 1951, during a skiing holiday in Davos, Switzerland, Ferry met with a member of the Tata family, industrialists from India. They wanted to build trucks and tanks in India with Daimler-Benz, having had good experiences working with Krauss-Maffei in locomotives production. Of course, West German firms weren’t allowed to build tanks at the time. So Ferry came up with a loophole: they would start a Swiss-based joint venture with Daimler for the tank design, thus circumventing the requirement that Germany not produce arms. The result: a Tata-Daimler factory in India that churned out tanks based on Ferry’s design.

A decade later, Krauss-Maffei and Daimler-Benz, now both under Flick’s control, returned the favor by bringing the Porsche company aboard the Leopard tank tender, to create the design. Harald Quandt thought he had the better plan, but he underestimated Flick’s political connections. Whereas Harald wanted to bring production to left-wing Hamburg, Flick proposed having the Leopard made in Bavaria, the conservative home of Franz Josef Strauss, Germany’s former defense minister and the mighty chairman of Bavaria’s ruling political party, the Christian Social Union (CSU). With Strauss’s backing, Flick and Ferry beat Harald; they were awarded the contract in 1963.

The Leopard tank was an enormous success. Flick’s Krauss-Maffei estimated its stake in the first contract at 408 million deutsch marks alone. Not long after, the armies of several of West Germany’s NATO allies were putting in their orders as well. About thirty-five hundred Leopard tanks had been built by 1966, and a new and improved model was soon ordered. Ferry Porsche had no qualms about the fact that his automobile firm had returned to arms development. “We never know in which direction politics will develop. According to the concept by which it’s structured, our army is based on the principle of defense. For this task we must equip it with the best weapons available,” Ferry wrote in one of his autobiographies.

Despite losing out on the Leopard, Harald continued undaunted with arms development and production. He led another consortium, this time to design the prototype for a German American tank. The expensive project failed to take off as well. Harald and Ferry were also busy designing their own amphibious cars. Ferry’s military prototype — none too different from his father’s bucket car — wasn’t picked up by the Bundeswehr. And Harald’s civilian “amphicar” was a flop worldwide. His IWK had more success making land mines, and the company supplied more than a million anti-personnel and anti-tank mines to West Germany’s military and many of its allies. Some of IWK’s anti-personnel mines were directly exported to or resold in African war zones. IWK’s unexploded mines have been discovered in Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Angola, among other countries. Intended to maim or kill soldiers, they may have ended up killing even more children and other civilians. Many of those land mines likely lie dormant beneath African soil to this day, long after the death of Harald Quandt.

8.

At 10:30 p.m. on September 22, 1967, Harald Quandt’s Beechcraft King airplane took off from Frankfurt Airport. Its destination was Nice, specifically Harald’s villa on the Côte d’Azur, which he planned on selling. Also aboard were his mistress and two other guests. The weather over Frankfurt was stormy that evening, and the pilots soon lost radio contact with air traffic control. The next day, a shepherd in the last foothills of the Alps found the remains of the private jet. It had flown into the mountains of the Piemonte region, not far from Turin. Harald, all his passengers, and the pilots were killed.

Harald was only forty-five years old when he died. He left behind his wife, Inge, their five young daughters who ranged from two months to sixteen years of age, plus twenty-two executive and supervisory board positions. These numbers were, however, surpassed by his half brother, Herbert, who had six children from three marriages and held more board positions than any other West German industrialist. When Harald died, the only German richer than the Quandts was Friedrich Flick.

Flick, as well as high-ranking officers of the West German and American military, attended Harald’s memorial service in Frankfurt. They paid tribute to an enterprising, charming industrialist who had loved people and parties. Harald’s closest associates were “filled with horror” at his early death but weren’t particularly surprised by it. They had long feared this day would come. Harald always prized living dangerously. After all he had witnessed and endured, he still had a childlike zest for life. This attitude stood in stark contrast to that of his conservative older half brother, Herbert, the visually impaired savior of BMW who didn’t like strangers. But in truth, Harald was the burdened one. One of Harald’s daughters once asked him whether she had so many siblings because he once had six of them himself. He didn’t respond kindly to that question. While these tragic matters weren’t totally taboo, they were largely left undiscussed. But Harald carried this macabre past with him wherever he went.

A German journalist once described running into Harald at a party in Frankfurt that was hosted by a famous Jewish architect: “Among the excited, cheerful faces, one, pale as the moon, gazed, still and silent with bright watery eyes … looking nowhere. The pale face, smiling politely but laboriously, remained motionless. It seemed to me as if a distant storm was raging behind those waxy eyes, a memory of an incurable misfortune. Harald Quandt, rich heir, son of Magda Goebbels … Everyone who looked at him remembered the terrible sacrifice of Baal that his mother had made in the Führerbunker when everything came to an end.” Harald never forgave his mother and stepfather for murdering their own children, his beloved siblings, nor did he ever get over their murder-suicide. When a lawyer representing Goebbels’s estate contacted Harald about his stepfather’s inheritance, he had wanted nothing to do with it. Harald told the lawyer that he preferred to cherish the memories of the house on Berlin’s Schwanenwerder Island — with his six siblings and mother alive in it.

Harald’s death tore the Quandt clan apart. At the same time, the Flick family was coming undone as well. One business dynasty would survive the inner turmoil. The other would fall apart.

9.

Baron August von Finck wore a blue suit of simple make and brown shoes with worn heels on the chilly day in early spring 1970 when a reporter from Der Spiegel magazine met him at his Möschenfeld estate, east of Munich. The journalist was there to profile the seventy-one-year-old for a piece on land reform. The collar and cuffs of the banker’s shirt looked threadbare, and his necktie hung askew. “It isn’t difficult for the old man to disprove the saying that clothes make the man. Beyond the billion-mark, the rules of peasantry apply once again,” the reporter wrote at the start of his twelve-page profile, titled “Nine Zeros.” The aristocrat “drinks little and smokes moderately — at most cheap straw Virginias, which disproves the proverbial saying that money doesn’t stink.” By 1970, Friedrich Flick, August von Finck, Herbert Quandt, and Rudolf-August Oetker made up West Germany’s top four wealthiest businessmen, in descending order of fortune. All four were former members of the Nazi Party; one of them had been a voluntary Waffen-SS officer; they had all become billionaires.

August von Finck in the 1970s.

ullstein bild – Sven Simo

The aristocratic financier’s private bank, Merck Finck, was valued at one billion deutsch marks, but the vast portion of his fortune lay in land. Von Finck’s main estate extended almost unbroken for twelve miles outside Munich. The five thousand acres of land on the outskirts of Germany’s wealthiest city — that’s two hundred million square feet of potential building land, worth about two billion deutsch marks at the time — was one-third meadows and farmland, two-thirds forest. On Sundays, the baron would drive his beat-up Volkswagen to the Bavarian countryside and trudge for miles through his forests, wearing a worn loden-green coat. In Bavaria, August von Finck was omnipresent. “It’s like the fairy tale of the hare and the hedgehog,” a union builder complained to the journalist from Der Spiegel. “Wherever we go — [von] Finck is already there.”

Bavaria’s richest man remained its stingiest as well. Von Finck didn’t carry small change. If he needed money, he drilled his unkempt fingers into his vest and mumbled, “Oh, don’t I have anything in my pocket?” He would accept coins with an open hand from anyone who stood nearby, and he hitched rides to the hairdresser in a nearby village because it was fifteen pennies cheaper than a haircut in Munich. He “doesn’t understand the world of necessary social change and doesn’t even want to understand it,” the reporter wrote. “As if in a museum, he continues to live in the era in which he grew up.” And von Finck wasn’t the only tycoon holding on to a darker era.

The former Waffen-SS officer Rudolf-August Oetker was still cozying up to Nazis. He hadn’t stopped at employing his old SS comrade von Ribben-trop or donating to Stille Hilfe. In the early 1950s, Rudolf-August’s second wife, Susi, left him to marry a prince who soon became a prominent politician for the NPD, West Germany’s neo-Nazi party. In 1967, at the pinnacle of the party’s fringe popularity, Der Spiegel reported that Rudolf-August privately met with some of the neo-Nazi politicians. He met the NPD’s founder through his ex-wife’s new husband while hosting another NPD leader at his mansion in Hamburg. In May 1968, the German newspaper Die Zeit included the Dr. Oetker and Flick conglomerates on a list of the NPD’s corporate backers. Both companies denied that they supported the party.

In late September 1968, despite massive protests, a public museum opened in Bielefeld bearing the name of Richard Kaselowsky, Rudolf-August’s beloved Nazi stepfather and member of Himmler’s Circle of Friends. To design the museum, Rudolf-August had commissioned the American star architect Philip Johnson, who had been a supporter of the Nazis as well. When the naming controversy flared up again decades later, the city council removed Kaselowsky’s name from the museum. In response, Rudolf-August pulled his funding from the museum, along with the artworks he had loaned to it.

10.

In December 1967, Adolf Rosenberger died as Alan Robert in Los Angeles from a heart attack. The persecuted cofounder of Porsche and émigré was only sixty-seven. After his settlement with the firm and the deaths of Ferdinand Porsche and Anton Piëch in the early 1950s, Rosenberger had traveled back to Stuttgart and met with Ferry. Rosenberger offered him patents and hoped to represent Porsche in California. After everything that had transpired, Rosenberger still wanted to be a part of the company he had helped establish. Ferry responded in a noncommittal way, and nothing came of it.

Almost a decade after Rosenberger’s death, Ferry published his first autobiography: We at Porsche. In it, the sports car designer not only twisted the truth of Rosenberger’s Aryanization and escape from Nazi Germany but also did the same with the stories of other German Jews who were forced to sell their firms and flee Hitler’s regime. Ferry even accused Rosenberger of extortion after the war. What’s more, the former SS officer used blatant anti-Semitic stereotypes and prejudice in his warped account: “After the war, it seemed as though those people who had been persecuted by the Nazis considered it their right to make an additional profit, even in cases where they had already been compensated. Rosenberger was by no means an isolated example.”

Ferry, now in his midsixties, supplied an example of a Jewish family who had voluntarily sold their factory after leaving Nazi Germany for Mussolini’s Italy, only to return after the war and claim “payment a second time,” at least according to his interpretation of events. Ferry continued: “It would be hard to blame Rosenberger for thinking in a like manner. He no doubt felt that since he was Jewish and had been forced out of Germany by the Nazis who had done so much harm, he was entitled to an extra profit.”

Ferry then falsely claimed that his family had saved Rosenberger from imprisonment by the Nazis. But it hadn’t been Ferry, his father, or his brother-in-law, Anton Piëch, who got Rosenberger released from a concentration camp in late September 1935, just weeks after the car moguls Aryanized his stake in Porsche. In fact, Rosenberger’s successor at Porsche, Baron Hans von Veyder-Malberg, had negotiated with the Gestapo for Rosenberger’s release and later helped Rosenberger’s parents escape Germany. But Ferry stole credit for these morally sound actions from the dead baron on behalf of the Porsche family: “We had such good connections that we were able to help him, and he was set free. Unfortunately, all this was forgotten when Mr. Rosenberger saw what he thought was an opportunity to make more money. However, not only Jewish people, but most emigrants who had left Germany felt the same way.”

11.

When their father died, Herbert and Harald “vowed to each other that there would be no fratricidal war in the Quandt house.” But after Harald died in the 1967 plane crash, the relationship between his widow, Inge, and his half brother, Herbert, deteriorated. Inge started dating her late husband’s best friend, who began criticizing Herbert’s business decisions. The two branches of the Quandt family initiated a separation of assets. After long, difficult negotiations, Inge and her five daughters received four-fifths of the dynasty’s 15 percent stake in Daimler-Benz from Herbert. Other assets were soon divided between the two families as well.

Inge was ill-suited to the life of a Quandt heiress. She became addicted to prescription pills and smoked about a hundred cigarettes a day. On the morning of Christmas Eve, 1978, Inge was found dead in her bed. She had perished from heart failure at fifty. She must have died with a cigarette in her hand, as two of her fingers were found to be scorched. Her daughters were orphaned, but yet another drama awaited them. The next evening, on the night of Christmas Day, Inge’s new husband lay down next to his dead wife, whose body had been laid out at home in Bad Homburg. He put a gun in his mouth and pulled the trigger. One of his stepdaughters discovered his body the next day.

Despite another tragedy for Harald’s daughters, at least they were well provided for. The Quandts had started shopping their Daimler-Benz stake around in 1973. The Flick family wasn’t interested. They were dealing with problems of their own. The Quandts quickly found another buyer. In November 1974, the families sold the stake. The buyer, initially kept a secret, was soon revealed: the Kuwaiti Investment Authority, the world’s oldest sovereign wealth fund. The sale was controversial in West Germany, coming hot on the heels of the 1973 oil crisis, but it netted the Quandt families almost a billion deutsch marks, the largest share transaction in German history. Harald’s daughters were set for life. As it happened, within six weeks their sale of shares was eclipsed by an even larger one: a Daimler stake, double the size, was sold for two billion deutsch marks by a Flick heir. The Flick conglomerate and the family who owned it were collapsing too.

12.

In the early 1960s, a heated legal battle had erupted between Friedrich Flick and his elder son, Otto-Ernst. Succession was at stake, as was the future of the Flick conglomerate, West Germany’s largest privately owned group of companies. As it had for Günther Quandt, dynastic and entrepreneurial continuity meant everything to Flick. But, unlike Günther, Flick never put in place the structures that would allow for smooth corporate succession as a way to pass the torch to his sons. To make matters worse, Otto-Ernst’s desire to separate himself from his controlling father turned him into an authoritarian and brusque leader in the Flick boardroom, alienating those he worked with.

Otto-Ernst was the opposite of his cool, cerebral, and calculating father. During one tense family meeting in Düsseldorf, which had been called to discuss Otto-Ernst’s professional future, he accused his father of being a coward. Flick responded that he “was the most good-natured person on the face of the earth, but not a coward,” adding that his son would soon find that out for himself in court. The verdict that Flick’s wife, Marie, delivered concerning her son was particularly brutal: “You were a person who justified great hopes. However, your few bad qualities have become so strong in the course of your life that … you lack the character requirements and the professional suitability to succeed your father.”

After more years of tense disputes, Flick finally concluded in late 1961 that Marie was right: his elder son just wasn’t cut from the right cloth. Flick amended his conglomerate’s shareholder agreement in favor of his younger son, Friedrich Karl, who was promoted over his eleven-year-older brother. In response, Otto-Ernst sued his father and brother for breach of contract, and he requested in court that the Flick conglomerate be dissolved and divided up.

The Flick family in 1960. Otto-Ernst at the far left, Marie and Friedrich in the center, and Friedrich Karl at the far right.

Berlin-Brandenburg Business Archive/Research Archive Flick

The court proceedings in Düsseldorf dragged on for years. Otto-Ernst lost two trials. An out-of-court settlement was reached in fall 1965. Otto-Ernst was bought out of the family conglomerate for about eighty million deutsch marks, and his 30 percent stake was transferred to his three children. His younger brother, Friedrich Karl, now controlled the firm’s majority of shares. Flick didn’t particularly approve of this son either, but he was running out of time and options for succession. He now set his hopes on his two grandsons — both sons of Otto-Ernst — who went by the names Muck and Mick.

Months after the conclusion of the settlement that tore her family apart, Marie died. Flick’s wife of more than fifty years had viewed both her surviving sons as incapable successors to her husband. Otto-Ernst “has always been talented, capable, and industrious, but he doesn’t get along.” Friedrich Karl “wasn’t talented, capable, or industrious, but he gets along.” That was her merciless assessment.

After his wife’s death, Flick, who suffered from a bronchial disease after a lifetime of smoking cheap cigars, moved from Düsseldorf to southern Germany for the fresh alpine air. He ended up taking permanent residency in a hotel on Lake Constance, just minutes from Switzerland. Flick died at the hotel, in his suite, on July 20, 1972, ten days after his eighty-ninth birthday.

13.

At the time of his death, Friedrich Flick was West Germany’s wealthiest man and among the world’s five richest people. He controlled the nation’s largest privately owned conglomerate, with 103 majority and 227 significant minority stakes, annual revenue of almost $6 billion, and more than 216,000 employees, including those who worked for Daimler-Benz.

And yet Flick had refused to ever pay a cent in compensation to those who performed forced or slave labor at factories and mines he controlled. In the early 1960s, the Jewish Claims Conference submitted a claim against Dynamit Nobel, an explosives turned plastics producer controlled by Flick. During the war, it had used about twenty-six hundred Jewish women from Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Poland as slaves to make ammunition in underground factories. The women were picked from the Auschwitz and Gross-Rosen concentration camps and deported to Buchenwald subcamps, where they were put to work for the explosives firm. About half of the women survived this ordeal. As it happened, Flick didn’t own Dynamit Nobel during the war. He became its majority shareholder only in 1959. Cruelly, he didn’t just reject the women’s compensation claims outright. Instead, he strung the negotiators along for years before pulling out of the talks entirely. Even John J. McCloy, the former US high commissioner for occupied Germany who had ordered Flick’s early prison release, got involved. He appealed to Flick’s moral obligation, but of course he got nowhere.

In the fifteen years before the claim concerning Dynamit Nobel landed on his desk, Flick had gained a lot of experience with negotiations for restitution. During that period, the mogul settled three highly complex Aryanization cases. Without admitting any guilt, Flick restored a mere fraction of the massive industrial firms he had forcibly bought or helped seize from the Hahn and Petschek families, who had all immigrated. Not only was he able to hold on to all remaining assets, but Flick even managed to turn a profit by negotiating government compensation for all the coal he had given up to the Nazi conglomerate Reichswerke Hermann Göring in the Ignaz Petschek Aryanization.

It wasn’t a surprise, then, when Hermann Josef Abs, the ubiquitous chairman of Deutsche Bank, struck a far more sober note during his eulogy at Flick’s memorial service in Düsseldorf than he had at Günther Quandt’s in Frankfurt. After settling with the Ignaz Petschek heirs for his own dubious role in the Aryanization, Abs mediated with the German government and Flick on behalf of the heirs. Ever the go-between, Abs then did the same for Flick in his callous dealings with the Jewish Claims Conference. At Flick’s funeral, Abs said that any assessment of the tycoon’s life’s work should be “left to more objective historiography than is currently customary in our so tormented and beaten country.”

It wasn’t just Flick’s — or his own — unholy dealings during the Third Reich that led Abs to this uncharacteristically morose declaration in late July 1972. In the 1960s the student protest movement had marked a cultural shift in West Germany. A more progressive generation had come of age, one that was born after the war and critical of the country’s power structures, the Third Reich’s continued stranglehold over high-ranking positions in virtually all aspects of society, and the lack of any real reckoning over Germany’s Nazi past. The old reactionary men who led Germany’s big industries were perplexed. They grew up in an era when authority was unquestionable and painful matters were simply swept under the rug. On top of that, after almost twenty-five years of relentless growth, West Germany’s boom economy was finally cooling off. Flick left behind a rapidly aging conglomerate and a disintegrating family tasked with keeping it all together.

Otto-Ernst didn’t attend his father’s memorial service in Düsseldorf. Almost eighteen months later, he succumbed to a heart attack — a broken man at only fifty-seven years of age. His younger brother, Friedrich Karl, wasted no time in making the Flick conglomerate his own, succeeding his late father as CEO. In mid-January 1975, he announced the sale of a 29 percent stake in Daimler-Benz to Deutsche Bank for two billion deutsch marks. There had been rumors floating around that Friedrich Karl was negotiating to sell the Flicks’ entire Daimler stake to the shah of Persia — the West German government found this unacceptable, especially since it came only six weeks after the sale of the Quandts’ Daimler stake to Kuwait. So, Deutsche Bank stepped in. Friedrich Karl needed the liquidity for urgent family matters. The next month, he bought out his nephews, Muck and Mick, and his niece, Dagmar, for 405 million deutsch marks. Thus Otto-Ernst’s three children were cut out of the family business, and Friedrich Karl now ruled over the Flick empire alone.

Unlike his stern, workaholic father, who preferred an austere lifestyle, Friedrich Karl enjoyed the trappings of wealth. He jetted between his mansions in Bavaria and Düsseldorf, a hunting estate in Austria, a villa on the Côte d’Azur, a penthouse in New York, a castle near Paris, and a two-hundred-foot yacht named the Diana II. His Munich parties were legendarily debauched. The Flick heir was smart but lazy and not overly interested in running the family business. He left that largely to his childhood friend, Eberhard von Brauchitsch, a dashing lawyer whom Flick senior had promoted to management. The two best friends now sat atop a pile of cash.

They made a deal with the West German Ministry of Finance: the billions from the sale of Daimler-Benz would be largely tax exempt, so long as the money was reinvested within two years into the German economy or in eligible assets abroad. So in the following years, several Flick-owned firms in Germany were upgraded, and hundreds of millions were reinvested in American businesses such as the chemicals company W. R. Grace. The tax exemptions for West Germany’s largest privately owned conglomerate were granted just in time.

But it all came crashing down in early November 1981, when tax authorities raided the office of the Flick conglomerate’s chief accountant in Düsseldorf; he was suspected of personally evading taxes. What investigators found was far more insidious: documents detailing that, for more than a decade, von Brauchitsch had paid almost twenty-six million deutsch marks in bribes to West Germany’s three largest political parties in order to facilitate the tax exemptions. A Catholic mission had been used to launder Flick-donated money back to the Flick conglomerate for cash distribution to its largest recipient: the CDU/CSU, an alliance of two conservative political parties, the Christian Democratic Union and Bavaria’s Christian Social Union. Von Brauchitsch euphemistically referred to the bribes as “cultivating the political landscape.”

The Flick affair, Germany’s largest political corruption scandal to date, shook the country to its core. Der Spiegel called it “the bought republic.” In the inquiry that followed, hundreds of current and former parliament members were implicated, including the new chancellor, Helmut Kohl. He got to keep his job, but his minister of economic affairs, Count Otto von Lambsdorff, was indicted for accepting bribes from the Flick conglomerate. He resigned his post. Friedrich Karl denied any knowledge of the payoffs and blamed everything on his friend von Brauchitsch. In 1987, the fired director was convicted to a two-year suspended prison sentence and a fine for tax evasion. Von Brauchitsch moved to Zurich and Monaco. He and Friedrich Karl remained close friends but seemingly out of necessity. Von Brauchitsch’s later memoir carried a telling title: The Price of Silence.

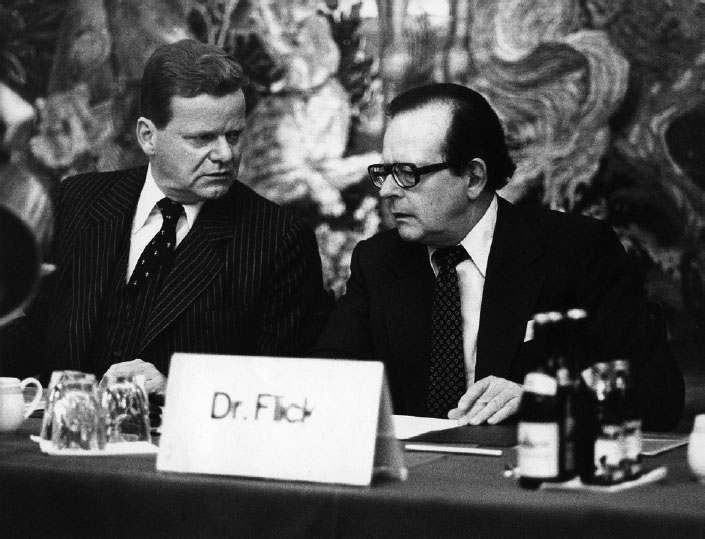

Eberhard von Brauchitsch and Friedrich Karl Flick, 1982.

ullstein bild – Sven Simon

By then the Flick conglomerate had ceased to exist. In December 1985, as many of the investigations into the Flick affair still went on, Friedrich Karl sold his entire business to Deutsche Bank for 5.4 billion deutsch marks ($2.2 billion), setting a new record for the largest corporate transaction in West Germany. Almost sixty years old, Friedrich Karl had had enough of big business. He cashed in and soon immigrated to tax-friendly Austria. Almost seventy years after his father started his first secret takeover of a steel firm, the Flick conglomerate dissolved. The bribery affair turned out to be one scandal too many for the notorious family business. As a German historian later concluded, all that remained of Friedrich Flick’s once mighty firm was “the enormous fortune of his heirs and the bad sound of a name.”

Like his father, Friedrich Karl steadfastly refused to compensate those who had performed forced and slave labor for the Flick conglomerate. He left it to Deutsche Bank to satisfy the claims of the Jewish Claims Conference against Dynamit Nobel. The bank did so promptly in January 1986, paying five million deutsch marks ($2 million) to those Jewish women who were still alive. A change was at hand in Germany, one that would dredge up the suppressed Nazi past of its most eminent business patriarchs.

14.

While the Flick empire was crumbling, other German business dynasties were imploding. The Porsche-Piëch clan had been generating headlines in the 1970s and ’80s, but not for exciting new sports car designs. It was rather their sordid, intrafamilial sex scandals and infighting over succession that made the news. Added to these somewhat typical dynastic squabbles was the threat of abduction. In 1976, one of Rudolf-August Oetker’s sons was kidnapped at the campus parking lot of the Bavarian university he attended. The student was held for forty-seven hours in a wooden box, where he received electric shocks. After his father paid a ransom of twenty-one million deutsch marks ($14.5 million) the young man was freed, but the ordeal left him disabled.

Still, of all the tragedies that could befall a business dynasty, a patriarch’s death remained the most dangerous. On a sunny day in late April 1980, Baron August von Finck collapsed behind his writing desk at his Möschenfeld estate and died. He was eighty-one. At the time of his death, the reactionary aristocrat was considered Europe’s richest banker, with an estimated fortune of more than two billion deutsch marks ($1.2 billion). He left behind the Merck Finck private bank as well as thousands of acres around Munich, some of the world’s priciest land. The baron had five children from two marriages. The “penny-pinching tyrant … subjected his five children to a Teutonic version of ‘daddy dearest,’ tightfisted and demanding, cold and remote,” according to a profile in Fortune magazine. Von Finck bought his only daughter out of his will for mere crumbs and disinherited his son Gerhard in 1978 for “leading a dishonorable lifestyle” after immigrating to Canada. (Gerhard now works as an upmarket real estate broker in Toronto, where he offers “a combination of German efficiency and Canadian courtesy” to his clients.)

This left von Finck’s three remaining sons to split the estate. The two eldest sons, August Jr. and Wilhelm, dutifully followed in their father’s footsteps and took over Merck Finck. Their younger half brother, Helmut, chose a different path. He joined the mystical sect of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh in Oregon. His arch-conservative siblings didn’t take a shine to this. In February 1985, the duo summoned Helmut to a Munich notary, where he was asked to sign over his inheritance in exchange for sixty-five million deutsch marks. He accepted, left the Rajneesh movement, and became a horse breeder in Germany. Five years later, his half brothers sold Merck Finck to Barclays for 600 million deutsch marks.

It took another two decades for Helmut to remember that he had been addicted to alcohol and drugs when he signed over his inheritance, and therefore, according to him, he had not been legally competent. His half brothers had also violated their father’s will by selling the family bank and other assets, Helmut argued. He sued, claiming the two owed him hundreds of millions of euros. In 2019, a court ruled that Helmut had been legally competent when he signed the agreement. He lost. Meanwhile, August Jr. had followed in his father’s footsteps in other ways. He took to financing far-right politics.

15.

While other business dynasties fought, faltered, and even faded, the Quandts somehow survived. In early June 1982, Herbert Quandt died unexpectedly from heart failure while visiting relatives in Kiel, weeks before his seventy-second birthday. Herbert left behind six children from three marriages. Like his father, he had transferred much of his fortune before his death. His eldest daughter, a painter, received shares and real estate. The next three children received a majority stake in Varta, the battery behemoth formerly known as AFA. He left the jewels of his fortune to his third wife, Johanna, and their two children, Susanne and Stefan. They inherited about half of BMW plus Altana, the pharmaceuticals and chemicals firm formerly known as Byk Gulden. When Friedrich Karl Flick immigrated to Austria, this last batch of Herbert Quandt’s heirs became Germany’s wealthiest family.

Even though Herbert surpassed his father’s success by saving and buying BMW, the visually impaired Quandt heir was unable to ever truly leave Günther’s shadow. At a memorial service in Frankfurt’s former opera house, Herbert’s closest aide remembered his boss as someone who “remained in his innermost being the son who found his pride in not having disappointed his father’s expectations.”

After his death, the two branches of the Quandt dynasty began to manage their fortunes in neighboring office buildings near Bad Homburg’s city limits. Herbert’s and Harald’s heirs are separated not only by a street and billions in net worth but also by different styles of doing business and contrasting outlooks: while one looks to the past, the other looks to the future. Whereas Susanne and Stefan Quandt’s office is housed in a plain brutalist building from the 1960s named after their grandfather Günther, Harald’s heirs make their investments in sleek bungalow-type offices adorned with greenery and named after their father and mother. They commissioned portraits of Harald and his wife, Inge, from Andy Warhol. Harald’s portrait hangs in the foyer of their family office. The other Quandts put a stern portrait of Günther above the reception desk and placed busts of the Quandt patriarch and Herbert in the entrance hall. Susanne and Stefan inherited immense economic responsibility through control over BMW and Altana. Harald’s daughters, on the other hand, invest their money freely, aided by their family office. They once got an offer to buy New York City’s Chrysler Building, but their mother couldn’t come to a decision. The two Quandt branches differ just as much as Herbert and Harald did: the older conservative, myopic sibling desperate to please his father; the younger one modern and forward-looking, in spite, or because, of everything.

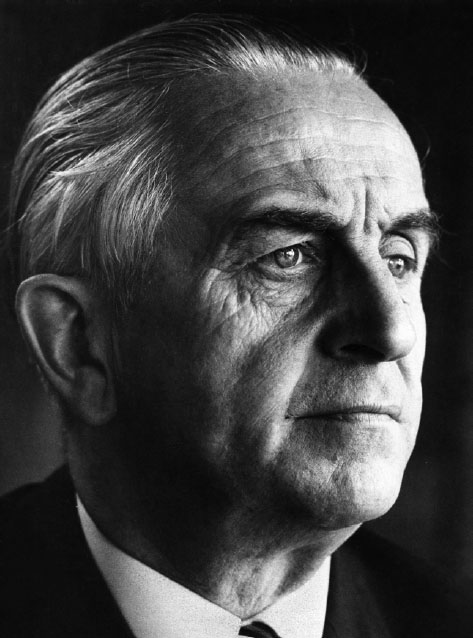

Herbert Quandt on his seventieth birthday, 1980.

ullstein bild – Würth GmbH/Swiridoff

In a stunning historical reckoning for the more modern Quandt branch, one of Harald’s five daughters converted to Judaism. When Colleen-Bettina Quandt was orphaned in 1978, she was only sixteen. Earlier that year, she’d first learned that her grandmother was Magda Goebbels, the First Lady of the Third Reich. Her family didn’t break the news to her — it had come from her Jewish boyfriend. Just like Magda during her teenage years in Berlin, Colleen-Bettina befriended a group of young Jews in Frankfurt. She too felt alienated at home, was searching for a way to belong, and became fascinated by Judaism. The news that a granddaughter of Magda Goebbels had a Jewish boyfriend spread like wildfire through Frankfurt’s tight-knit religious community. “In the end, the whole Mishpacha knew,” she later told a biographer of the Quandt dynasty. Not everyone in the Jewish community welcomed her with open arms. Some of her friends’ parents even refused to talk to her.

Colleen-Bettina ended up moving to New York City to study jewelry design at Parsons School of Design. As in Frankfurt, most of her friends in New York were Jewish, and it was there that she decided to convert to modern Orthodox Judaism. In 1987, at age twenty-five, Magda’s granddaughter converted in front of three rabbis. Soon after this event, she met Michael Rosenblat, a German Jew who had moved to New York to work in the textile trade. Rosenblat grew up in an Orthodox Jewish household in Hamburg. His father had survived a concentration camp. His family now had to get used to the fact that he was dating not just a convert but also the granddaughter of the Third Reich’s most notorious matriarch.

But love prevailed. In 1989, the German couple married in a New York synagogue. Colleen-Bettina was glad to lose her maiden name. “Quandt, this name only annoyed and destroyed. Bodyguards, conflict, endless loneliness. Terribly envious people and hypocrites — I don’t want to have anything to do with that anymore,” she told a German journalist in 1998. She and Rosenblat had divorced the year before, but she carries his surname to this day.