9

Presidents, Protection, and Politics

Political Cartoons in the Irish World and American Industrial Liberator, 1890–1913

Úna Ní Bhroiméil

In the ferment of newspapers that proliferated in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century New York, the ethnic Irish American newspaper, the Irish World and American Industrial Liberator, plied its trade and jostled for position. Using the journalistic genre of political cartoons to command attention and to communicate its editorial opinion, its editor, Patrick Ford, decided and defined the relevant issues for his readers whether Irish or American.

The period 1890–1913 is an interesting era for the newspaper as it is sometimes regarded as a politically “quiet” time in Irish political history—“after” Parnell and “before” Home Rule. For an ethnic newspaper in New York, this, then, is an ideal period in which to investigate the paper’s focus on American politics and policies. This chapter will examine and probe the political cartoons published in the Irish World from 1890 to 1913 to reveal the disposition of the paper, the temper of its readers, and the ambiance of the era in the United States.

The Irish World

Patrick Ford’s Irish World, and from 1878, Irish World and American Industrial Liberator, was the highest circulation Irish American paper in the United States during the period 1890–1913. Its circulation rose from 35,000 copies in 1876 to 100,000 in 1884, with a readership of 20,000 in Ireland in 1880.1 By 1900 its circulation had increased to 125,000, and although this number declined to around 60,000 in 1914, its publication in New York had the advantage of being in the center and hotbed of American newspaper publishing at the turn of the century.2 The title of the newspaper attests to its interest in encapsulating the Irish world in its entirety. Whether it existed in Ireland, America, or elsewhere, the Irish World reported on it and stated on its masthead that it was “committed to the Irish race throughout the world.”3 But, it was not simply an Irish paper in America. Its secondary title, American Industrial Liberator, demonstrated the support of the editor, Patrick Ford, until his death in 1913, for labor in the United States. David Brundage points out that Ford “drew parallels between the land struggle in Ireland and the labour struggle in the United States,”4 and his paper supported the policies of Henry George in the 1880s as well as the Land League in Ireland.5 Published on Saturdays as a weekly paper, it supported Irish nationalism, and Home Rule in particular, until 1914 when it broke with John Redmond because of his support for Britain in the Great War.6 Ford’s paper was consistently anti-imperialist and heralded the British empire as the root of all evil, not merely in Ireland but around the world. On that basis the Irish World supported O’Donovan Rossa’s dynamiting campaign of British cities in the 1880s, the Boers against the British at the beginning of the twentieth century, and espoused a strong campaign of United States’ neutrality on the outbreak of World War I in 1914 while being anti-British and pro-German at the same time. Under the Espionage Act of 1917, the paper was banned from the US mail because of its anti-British sentiments.7

In its editorials, the Irish World stressed that it was nonpartisan in American politics and that it did not automatically support one political party no matter who the candidates or what the platform.8 It was, however, “political” in that its editors believed in shaping the political debate and influencing voters. One of the ways in which it transmitted its views to readers was through publishing “political” cartoons that commented on contemporary national and international affairs. Political cartoons had initially found a place in illustrated journals such as Harper’s Weekly, which had carried Thomas Nast’s powerful cartoons since 1862, and in other publications such as Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Journal and the New York Daily Graphic.9 The 1884 presidential election displayed the clout of the political cartoon in electoral terms when a cartoon published by Pulitzer’s World linked candidate James G. Blaine with corruption and the moneyed classes and was credited with his loss of New York State by 110 votes and, consequently, the presidency.10

This graphic journalism became a fundamental feature of what became known as “New Journalism,” and in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, newspaper editors and publishers hired editorial cartoonists to improve their circulations and enhance their reputations. The potential of the political cartoon to expose those in public life was demonstrated by the effort of Republican political boss and New York senator Thomas Platt to present an anticartoon bill to the New York State Legislature in 1897.11

This formidable tool of pictorial journalism was one that the Irish World used to great effect in the period 1890–1913. While an in-house editorial cartoonist was expensive and many immigrant newspapers could not afford one, the Irish World used cartoons accredited to other newspapers regularly from the 1880s on and, from 1900, carried a front-page cartoon directly under the masthead. In 1901 the front-page cartoons were mostly taken from and accredited to other newspapers. However, Charles Pickett drew a number of cartoons for the paper from 1901 to 1904, and from 1904 on, the paper had a cartoonist, Thomas J. Fleming, who drew a weekly cartoon for the front page.12 The political cartoonist had, therefore, a strategic opportunity to convey in one single panel an editorial position. He was most likely hired for his political alignment with the paper and his ability to convey the editorial viewpoint succinctly through visual expression, encapsulating “a complex of political and social ideas, distilling them into one illustration with accompanying caption.”13

Political Cartoons

As Edwards and Ware have stated political cartoons function as “windows to the political world.”14 Because they are time based, drawn in response to contemporary events, and focused on a particular “critical discourse moment,”15 they are not always easy to interpret when looking back at them from the present. Indeed, Elisabeth El Rafaie has pointed out that even current cartoons can be difficult for readers to understand as they require “a broad knowledge of past and current events, a familiarity with the cartoon genre, a vast repertoire of cultural symbols, and experience of thinking analytically about real-world events and circumstances.”16 But this historical hurdle can be mitigated by placing the cartoon in its original context and into the framework of the newspaper in which it was published. The Irish World, by printing its primary political cartoon consistently on its front page, drew readers’ attention in a visual way to the editorial position of the paper. Joel Wiener maintains that many editorials in American newspapers went unread,17 and so the sight of a one-panel cartoon that could be taken in quickly and in a single scan would “entrap the eye” and draw readers in more readily than multiple columns of gray text. Both, however, were facets of the New Journalism.18 The cartoon, though, was, in essence, a “kind of shorthand.”19

The ability of political cartoons to shape and influence the opinions of its reading public is a contested one. The persuasion of readers fits with what Wiid, Pitt, and Engstrom term the “strong” theory of political cartoons in that they can mold “public attitudes, intentions and behaviors.”20 Medhurst and DeSousa describe cartooning as a form of persuasive communication. They argue that through “dispositional forms” such as contrast, contradiction, and commentary, as well as the “use of line and form, exaggeration of physiognomical features, placement within the frame, relative size of objects, relation of text to visual imagery, and rhythmic montage,” the cartoonist can reveal some “truth” about the character or situation and thus literally draw the attention of readers to what they want them to see.21 Scrutinizing political cartoons for all or some of these “signs” can provide insight into what a cartoonist intended to convey to readers of a particular newspaper, although it is difficult to gauge what the impact of the cartoon actually was on the reading public at any given moment.22 Nonetheless, the editor of the Irish World, by employing a regular cartoonist after 1904, clearly expected to influence his readers on specific issues whether they related to national or international events. The consistency of the artistry of the cartoonist, the symbols he used, and the placement of the cartoon gave readers of the Irish World a familiarity with the cartoons and a better chance of interpretation than with random cartoons seen out of context.

Many scholars have pointed to the “weak” theory model that political cartoons reflect contemporary public attitudes,23 and Fischer states unequivocally that they rely and build upon the “a priori beliefs, values and prejudices” of readers.24 Without some recognition by readers of the symbols, referents, and allusions used in the cartoon, it would fail and would therefore be pointless. This use or exploitation of conventions which Fischer states are in “fundamental harmony with the cultural literacy of the public”25 are devices used by the cartoonist to tap into the prevailing attitudes and beliefs of the readership of the newspaper so that the cartoon will ultimately “work.” Recurring visual cues allowed the reader to participate in constructing a political position or identity for themselves and allowed readers to participate in a democratic manner in political debate.26 Decoding the cartoons, therefore, allows the historian to discern traces of the views of the readership at various times in the life of a newspaper. They are for this reason a potent and powerful tool in the historian’s armory as this is one of the few methods of tracking the remnants of contemporary public attitudes in the past.

Range of Cartoons and Selection of Themes

For the purposes of this chapter, all the weekly editions of the Irish World published between 1890 and 1920 were examined, and all the front-page cartoons were collected. Cartoons were also collected from elsewhere in the paper in the period before 1904 when Fleming became the paper’s regular cartoonist. The aim was to capture a wide range of cartoons and to allow specific categories and themes to emerge from the data.27 Putting aside all those cartoons that dealt solely with Ireland, this study focused on cartoons that dealt with events in America or about America. This was done in order to determine the engagement of the paper and its readership with American politics and policies and to identify the positions Irish Americans took in relation to national events in particular during this period. Four key themes came into view: presidents and their personalities and records, the economic policy of protection and tariffs, the threat that Japan posed to America internally and externally, and the overall influence of Britain on America and Americans, and the threat that it posed to America.

Presidents

Six men served as president of the United States during the period 1890 to 1913: Benjamin Harrison (Republican) 1889–93; Grover Cleveland (Democrat) 1893–97; William McKinley (Republican) 1897–1901, assassinated; Theodore Roosevelt (Republican) 1901–09; William Howard Taft (Republican) 1909–13; and Woodrow Wilson (Democrat) 1913–21. The Irish World published no cartoons of Benjamin Harrison and only one each of Grover Cleveland and William Howard Taft. The majority of the Irish World front page and other political cartoons focused on the presidency of William McKinley and on his foreign policy during the period of the Spanish-American-Cuban War, 1898–1903. The Irish World was ideologically opposed to what it termed the United States’ policy of imperialism and castigated McKinley’s policy of “benevolent assimilation” and the “civilization” of the Filipino people. Although Press has noted that, during a national crisis, there is normally a “rally effect” where newspapers, and especially cartoonists, rally around a president and his policies in a burst of national patriotism, this was not the case with the cartoons carried in the Irish World.28 In his Cuban message to Congress, which brought the United States into the war with Spain, McKinley controversially stopped short of recognizing the Cuban republic as he believed that Cubans were incapable of self-government.29 The Philippine Republic, newly declared by revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo in June 1898, was not recognized by the US government either. In February 1899, the United States annexed the island under its treaty with Spain enforcing, as Paul Kramer points out, “its ‘sovereignty’ in the Philippines against a newly internal ‘insurrection.’”30 The ensuing Philippine-American War and the McKinley Philippine policy of benevolent assimilation toward “our little brown brothers” drew the ire of the Irish World, and much newsprint was given over to the wrongs McKinley was perpetrating on the Philippines with his imperial mindset. It is the cartoons, however, that bring the position of the Irish World into sharp focus. By devoting a series of cartoons over time to a regular and growing readership, there was the opportunity to communicate to readers what might have been ignored or lost in long and textual editorials or columns.

In many of the cartoons, McKinley is seen as acting contrary to the values of the United States. In a cartoon taken from the New York Herald and printed on the front page of the Irish World on August 5, 1899, McKinley and General Otis, the military governor of the Philippines, conspire to censor reports and accounts of United States’ atrocities in the war.

Whispering into Otis’s ear, the darkly drawn McKinley conveys an air of secrecy and scheming and an effort to keep the truth from the American people as represented by Uncle Sam. Standing sidelined with a pencil and blank paper under his arm, Uncle Sam looks askance at the actions of McKinley, even as he clearly sees the gravestones and prone figures lying on the ground. While Otis was being condemned by newspaper correspondents for his censorship regime, in which he threatened to charge any correspondent with espionage if he sent reports of what was actually happening in the Philippines home rather than the manipulated and censored “facts” that Otis deemed “advisable,” his size in the cartoon makes it clear that he was subordinate to McKinley and a mere minion in this collusion.31 This view was reinforced by the text, especially by the quotation from Otis added by the Irish World to the original cartoon and which stated that Otis was in fact under instructions from McKinley to act as he did. The placement of the cartoon on the front page of the newspaper was a deliberate act by the editor to point the finger of accusation directly at McKinley and at presidential policy and was a very provocative act in time of war.

9.1. Irish World, August 5, 1899.

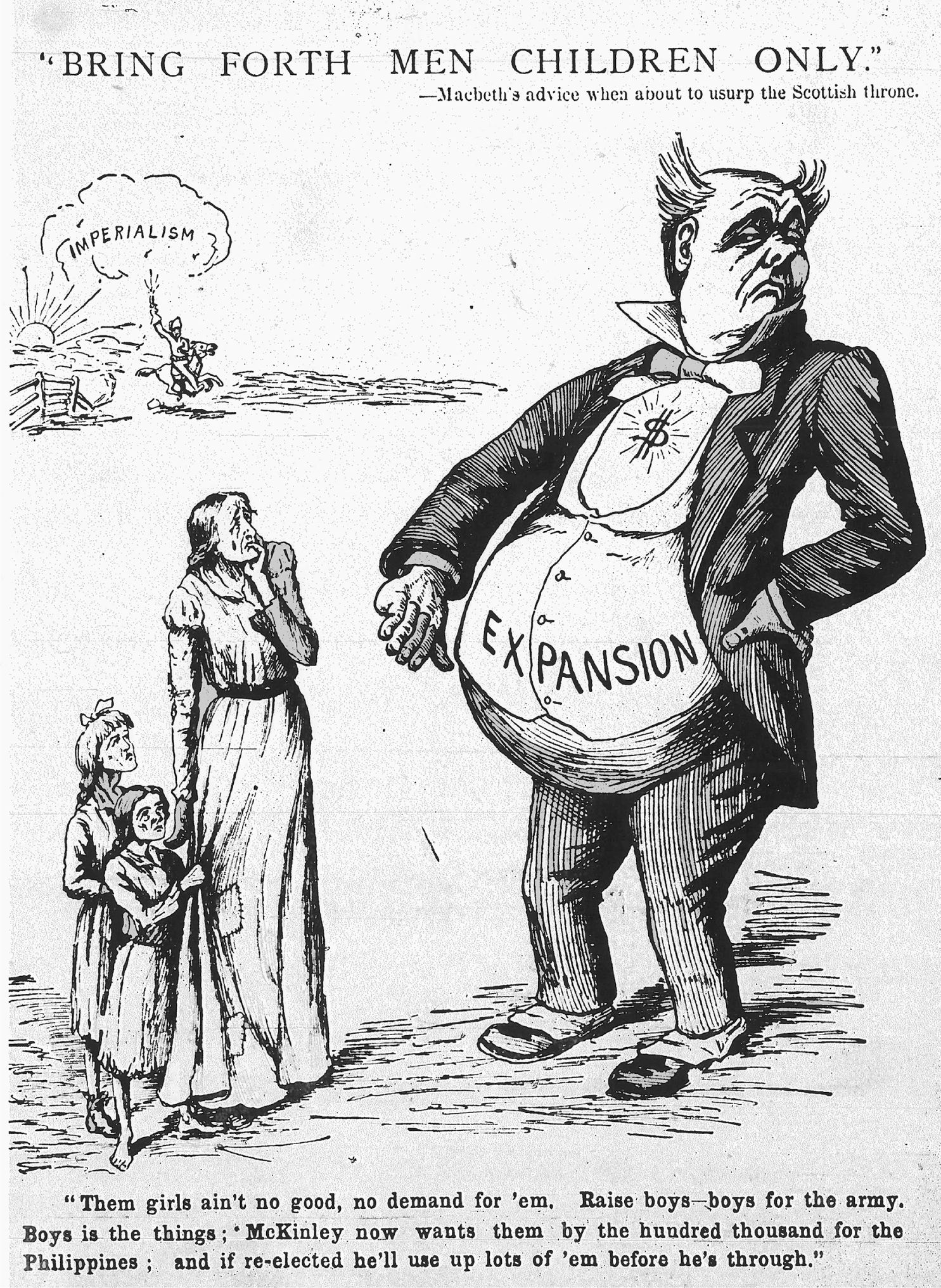

But the war was popular in the United States, and the opposition to it was generally fragmented and fruitless.32 McKinley ran on a platform of prosperity and victory in the presidential election of 1900, and this led to a renewed focus on McKinley as the architect of the rush to imperialism. On October 13, 1900, the Irish World printed its own front-page cartoon of McKinley as a bloated figure after expansion, supported by financiers and industrialist donations through his campaign manager Mark Hanna,33 denoted by the prominent dollar sign on his shirt, and poised to win the presidency for the second time.

9.2. Irish World, October 13, 1900.

In attempting to persuade its readers not to vote for him, the cartoon’s text compared McKinley to Shakespeare’s Macbeth before seizing the Scottish throne, when he stated “bring forth men children only” to his wife. This quote in the play commends the manly characteristics of force, violence, and ruthlessness displayed by Lady Macbeth, and as used in the cartoon, suggests McKinley’s affinity for these qualities. Even if the readers were not familiar with the exact meaning of the literary quotation, it clearly taps into the debates in the United States between imperialists and anti-imperialists, particularly during the election of 1900.34 The nation, according to imperialists, was becoming more manly—it was youthful, vigorous, and male, expanding in the world to fulfill its manly destiny, and was leaving behind the domestic space occupied by women where it would become passive and frail. The anti-imperialists were portrayed as old and musty and as women. The prevalence of this “national manhood metaphor”—that the United States had become a man—is reflected in this cartoon and is immersed in the contemporary conversations around manhood and manliness.35 McKinley, previously accused of having no backbone and thus of not being “manly” enough to use force before the declaration of war against Spain, is now portrayed as so in thrall to bellicose manliness that he has no time for women or girls.36

Anti-imperialists also portrayed American mothers as strongly opposed to the war, and this is captured in the cartoon in the second section of text below the image. Using a Mr. Dooley quotation, the cartoonist focuses on the need for boys as American soldiers and on the possibility that they will be maimed or killed in the war. This brings the eye back to McKinley’s disdainful treatment of the mother and daughters in the cartoon, fearful and pleading and dressed shabbily, with one girl barefoot. If their husbands and fathers and brothers are to be destroyed by war, what will become of them? The cartoon suggests that McKinley will not be the person to approach for help in that event. While McKinley looms large in the cartoon and is without doubt the prime mover in the continuation of the war, in the top left-hand corner is a small, horse-riding figure shooting a gun in the air, having broken through a fence. He rides alongside a sea, a rising sun behind him and the cloud of imperialism above him. This is likely a reference to Theodore R. Roosevelt and his “Rough Riders” cavalry. Roosevelt, as McKinley’s vice president, was eager for imperialism and vociferous in his support for vigorous, manly pursuits such as war. These scenes—an uncontrolled war, a loss of male citizens, and contempt for the women left behind and for their characteristics—are therefore ones that the voters should expect to encounter if McKinley won the presidency.

McKinley did, winning 51.6 percent of the popular vote. The Irish World’s voice, as with many of the anti-imperialist opposition, could not detract from the popularity of McKinley and the Republican campaign in 1900. What the cartoons demonstrate, however, is the condensed message of the paper’s columns of newsprint at a given historical moment. Those columns reveal the complex interplay of contemporary debates and discussions and the concentrated effort to communicate the paper’s position to its readers. Janis Edwards suggests that the “stories” cartoons tell about their subjects can be more revealing than any one cartoon by itself. The story depicted in the twelve cartoons featuring McKinley as a central character in the Irish World, from the first one in 1899 to the last in November 1900, just prior to the election, was that he was the driver of the imperial policy of the United States, careless about the knowledge and welfare of the citizens of the republic, and therefore a destructive force.

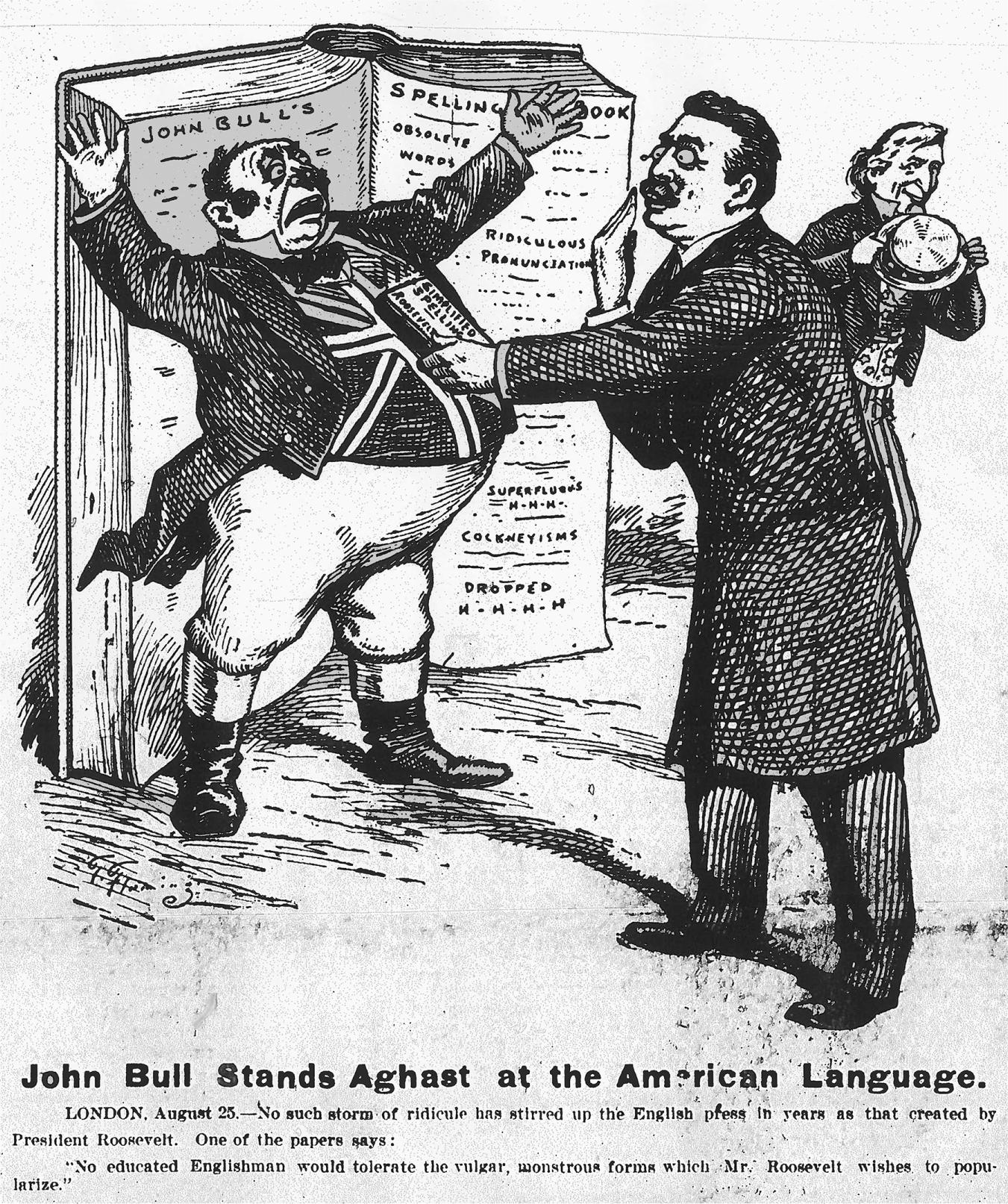

None of the antagonism displayed so clearly by the Irish World toward McKinley was directed at Theodore R. Roosevelt, his vice president and successor upon his assassination in 1901. On the contrary, although the Irish World printed two anti-imperial cartoons on July 5, 1902, and December 19, 1903, neither of them featured Roosevelt. The 1902 cartoon featured contrasting images of the crest of the Rochambeau Monument that had been dedicated in Washington, DC, that year representing Lady Liberty protecting the American eagle from the British lion and a threatening American eagle attacking a helpless Filipino.37 The 1903 cartoon, taken from the Columbia Daily Express, saw an overwhelmed Uncle Sam in military dress dealing with the problems of being a world power as Columbia gently asked him if they had been happier in their old (isolationist) home. Both cartoons appeared on the front page of the paper and marked the continuing ideological opposition of the Irish World to the trajectory of American foreign policy. The villain in these cartoons was not personalized as it had been with McKinley, however. The policy of imperialism was presented through emblematic American symbols and not as the figure of the president representing the nation. In fact, as the 1904 presidential election approached, the Irish World printed a flattering lifelike line drawing of Roosevelt above a wide and lengthy column listing his labor record and his “favourable action on labour legislation.” In the aftermath of Roosevelt’s victory, the paper celebrated the result by printing many pages containing congratulatory messages from other newspapers on its “potent influence” in bringing about the “overwhelming victory of Roosevelt.”38 By March 1905 the paper was extolling the honesty of Roosevelt in recognizing Irish American contributions to the American Revolutionary War and Civil War as well as his statement that pride of race did not lessen patriotism.39 The only cartoon featuring Roosevelt in the Irish World appeared on the front page on September 8, 1906, after Roosevelt signed an executive order in August mandating the use of the Simplified Spelling Board’s list of “American” spellings of English words.40

Picturing a horrified John Bull defending a spelling book of “obsolete words,” “cockneyisms,” and “dropped h’s,” Roosevelt presents him with a book entitled the “President’s American” instead of the “King’s English.” A delighted Uncle Sam looks on. This separation and setting apart of the American version of the English language was the subject of another front-page cartoon on September 22, 1906, when Roosevelt’s name appeared on the primer in the schoolroom. Glorying in the appalled reaction of the British press to Roosevelt’s decision, the Irish World cheered visually and applauded Roosevelt’s action.

But it is the absence of Roosevelt from political cartoons in the Irish World that signifies the paper’s support for him as president during this period and the benign way in which the paper regarded him. This is telling as it provides an insight into how the paper saw the political cartoon at the time as a weapon to punish and to identify the object of derision of the paper and of its readership. “The power of the political cartoon is not in its direct, persuasive effects, which are contestable, but in the way it frames and defines what is at issue,” according to Edwards.41 The political cartoons during the tenures of McKinley and Roosevelt all identified the imperial policy of the United States as what was at issue but, as Greenberg states, the cartoon also frames a contemporary political issue by “diagnosing causes, making moral judgments, and suggesting remedies.”42 Though McKinley and Roosevelt were both Republicans, and both were expansionists, the Irish World identified one as the problem, marked him as a purveyor of censorship, violence, and disregard for the American people and their values, and suggested rejection by the electorate. His vice president on the other hand, associated with the same policies and outcomes, was supported and celebrated. Ideologically and politically, this seems to make no sense at first glance.

9.3. Irish World, September 8, 1906.

The support for the Republican Party is interesting in the Irish World. By the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Irish Americans were more usually associated with the Democratic Party and the city boss system in the United States.43 One of the reasons the Irish World was pro-Republican was because of its stance on protective tariffs for American industries. The Irish World had supported the Republican James G. Blaine throughout the 1890s on this issue.44 The Republicans supported economic nationalism through governmental control of trade, mostly through protective tariffs and import restrictions so as to protect the national market from international competition.45 This, ironically, was encapsulated most obviously in the McKinley Tariff of 1890, though while the Irish World printed a full “protection issue” before the election of that year, its front-page cartoon focused on the British threat to the United States from the free-trade plank of the “Anglo Democratic support” and of the “Anglo Mugwump support” rather than on the “true” Republican protection policy.46 There was no sign of McKinley in the image. Throughout the 1890s, the Democrats under Grover Cleveland reduced the tariffs and the Republicans under McKinley raised them.47 Marc-William Palen argues that Cleveland’s free-trade policies were anti-imperial in that the Democratic Party wanted to extend free trade to avoid having to annex territory. The imperial acquisitions of the Republican administrations, however, allowed the United States to practice protection at home but to have the advantage of reciprocal treaties and foreign markets abroad.48 This suggests, therefore, that the editor and readers of the Irish World, in supporting protectionism and tariffs, were economic Republicans but foreign policy Democrats. This could account for the paper’s antagonism toward McKinley for his Philippine policy.

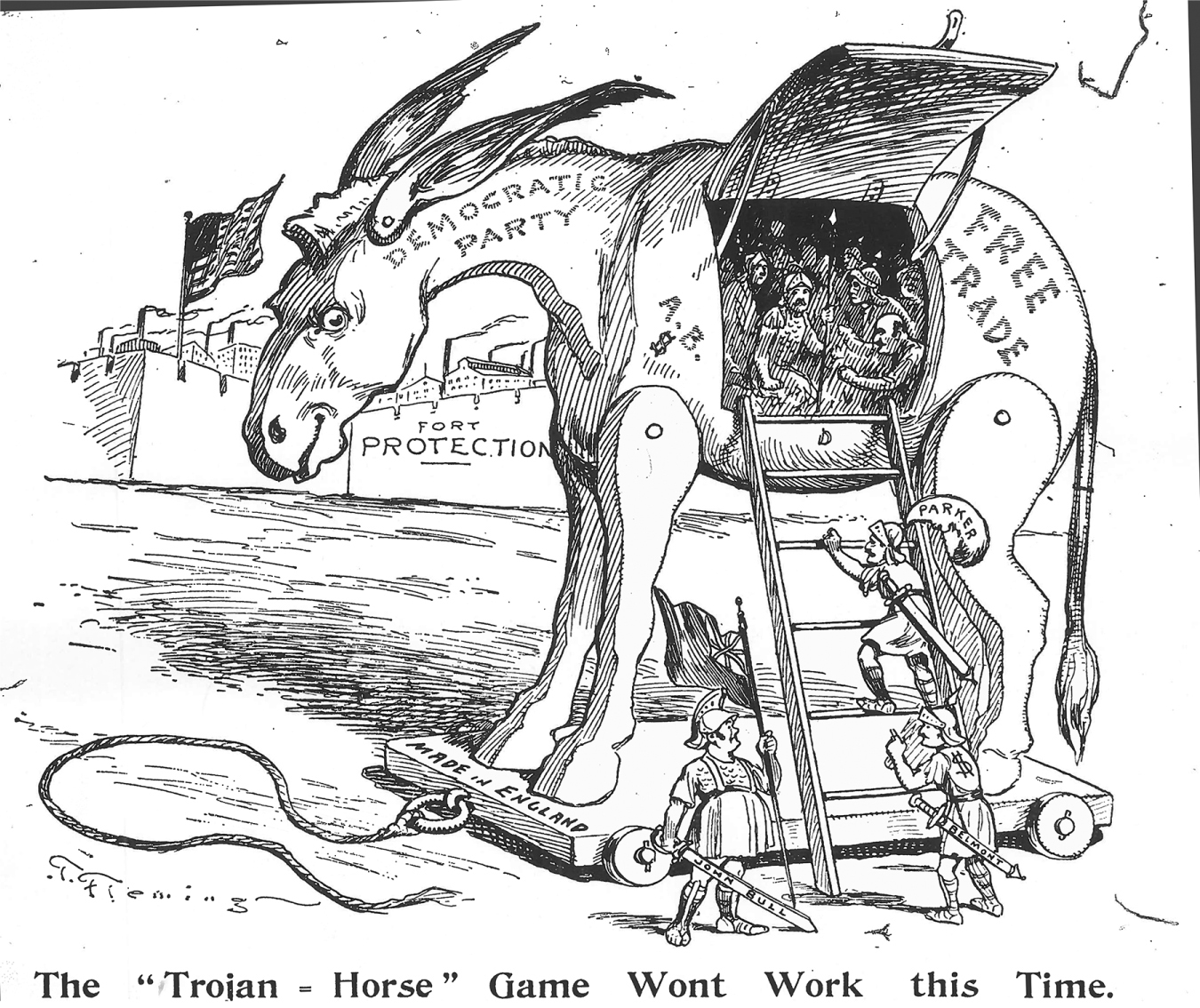

9.4. Irish World, September 24, 1904.

The cartoons published in the paper until 1909 featured the Democratic donkey49 prominently—as a “horse” needing to be broken,50 as a Trojan “horse,”51 and as a “horse” wearing a Belmont bridle.52 Contemporary readers in 1904 would have easily recognized the reference to the racehorse owner, breeder, and builder of the Belmont race track in New York, August Belmont, the son of August P. Belmont, who had been chairman of the Democratic Party.

He was also identifiable in the cartoon as one of the wealthy financiers backing the free-trade Trojan “horse” in attempting to gain entry to America’s “Fort Protection.” Both he and the Democratic candidate Alton B. Parker, who had been a judge in the New York Court of Appeals and who had declared the eight-hour law unconstitutional, were portrayed climbing up a ladder into the Trojan horse.53 Etched on the wooden body of the Democrat donkey were the initials “A.B.” and a dollar sign as well as the words “free trade.” All these elements together conveyed a message of wealthy investors and antilabor candidates literally inside the Democratic Party, scheming to bring in free trade and usurp one of America’s core protectionist values. The fort, a symbol of protection in itself, clearly houses factories within its walls as can be seen from the smoke coming from the industrial chimneys on the factory buildings. In dedicating four cartoons to the protection issue in the month leading up to the 1904 presidential election, the Irish World staked its claim to supporting tariffs and the Republican candidate Roosevelt and opposing the Democrats and their candidate Parker. There was no sign in any cartoon of the Socialist candidate Eugene Debs.

The cartoonist used the full range of a bank of images in relation to the protection and tariffs issue. The Trojan horse cartoon referenced Virgil’s Aeneid and the commonplace phrase “to look a gift horse in the mouth” in the accompanying text. The cartoon published on October 29 referenced the biblical story of Samson and Delilah, with “Miss Democracy” holding a free-trade scissors to cut Uncle Sam(son’s) hair.54 Rebuffing her, Uncle Sam refuses the haircut and maintains his strength. While both of these cartoons reference the past and assume an education or a familiarity with the Bible on the part of the paper’s readers, the cartoon published on October 22 showed a modified image of a gramophone with the Democratic donkey instead of a dog, referencing the Victor Talking Machine’s logo while the text mimicked its catchphrase “his master’s voice.” This allusion to contemporary life in the United States is supplemented by the text underneath the Trojan Horse cartoon. Referring to an era of “search lights and x rays,” the cartoon text makes the point that a Trojan horse would not fool people on this occasion because of new technological advances. In using these contemporary cultural references, the cartoonist related the image to readers’ lives and experiences and also suggested that Americans were too advanced to be taken in by such old-fashioned scams as a Trojan horse.

The later cartoons in 1909 and 1911 draw on the idea of a tariff wall made of bricks that can be built up or taken apart brick by brick, as suggested by the Irish World in the case of the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act of 1909 or friendly neighbors talking over a wall in the case of Canada’s and the United States’ reciprocity treaty of 1911.55 The most iconic image used by the cartoonist was that of George Washington stalling a woodcutter congressman’s hand (Payne) in cutting down the protection of American industries tree in 1911 and relating the protection issue to a founding principle and to an honest and virtuous politician. The cherry tree myth was well known to all Americans and was carried in the McGuffey readers used in American schools.56

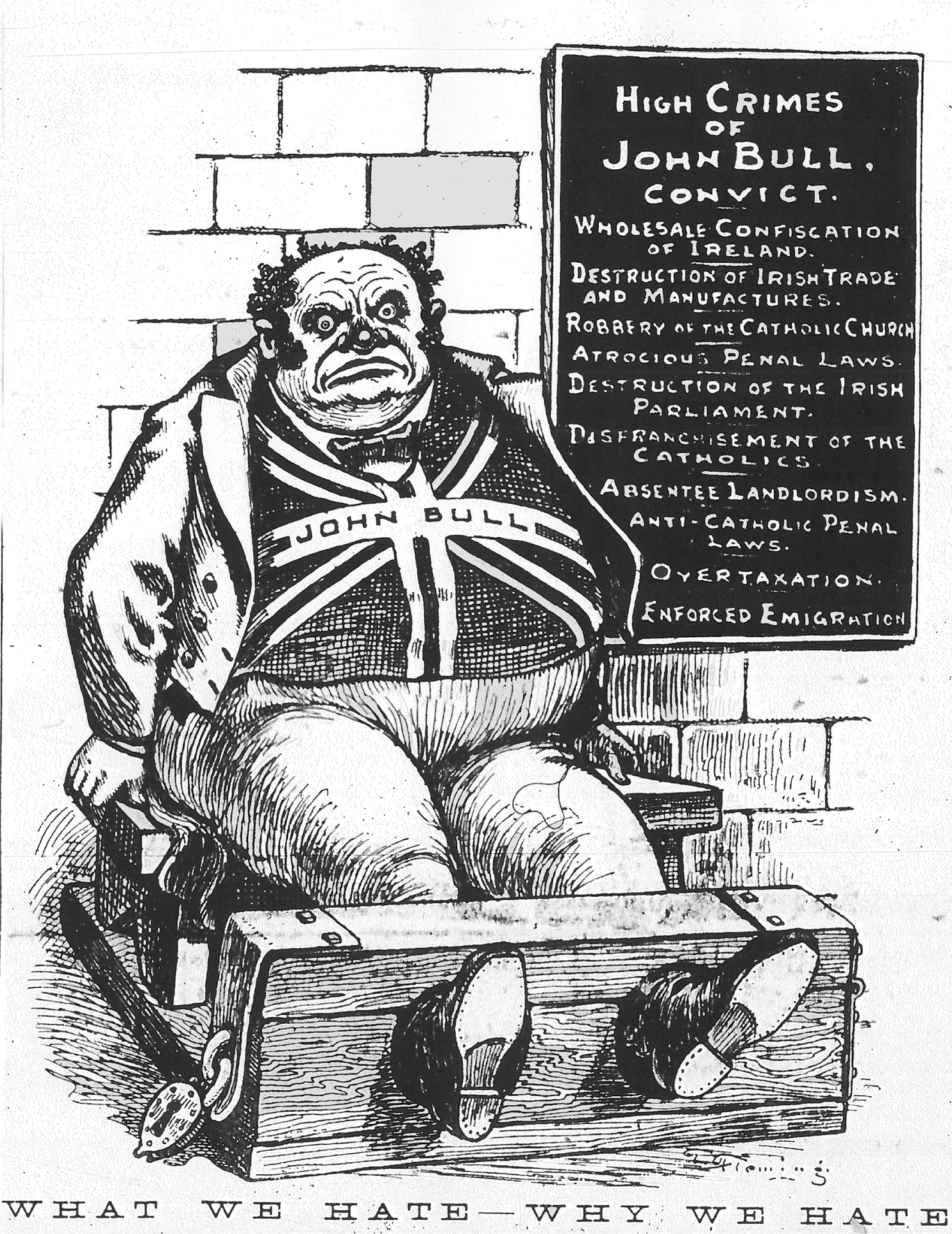

These tropes of American life and symbols of American cultural literacy were offset by the consistent appearance in these cartoons of John Bull representing the British Empire. The Irish World was implacably opposed to the British Empire because of its treatment of Ireland and captured the essence of its opposition in a cartoon published on April 22, 1905, entitled “What We Hate—Why We Hate,” featuring the convict John Bull in stocks and a list of his high crimes against Ireland.57

The appearance of John Bull in Irish World cartoons was therefore well established and would have been familiar to readers of the Irish World as a threatening, sly, and untrustworthy figure in relation to Irish affairs. Including this symbol in cartoons that dealt specifically with American issues was designed to evoke emotions and connotations with previous representations, and this symbol’s interocularity conveyed the same message to readers in the American context as it did in the context of Ireland. The very presence of the John Bull symbol in a cartoon signified menace and intimidation even if the character did not appear himself to be dangerous.

There was in America at the turn of the century what Stephen Tuffnell terms “a discourse of Anglophobia” that came to the fore as the United States became more commercially prosperous and industrially powerful at the end of the nineteenth century, and which became a cipher and a “negative referent in the expression of a positive sense of American nationality.”58 At the same time, there was a discourse of Anglo-Saxonism celebrating racial exceptionalism and the civilization of the race, particularly in relation to overseas conquests and the advent of an American imperialism after 1898. This led to an era of rapprochement between Britain and the United States, especially after 1910.59 This trend of celebrating Anglo-Saxonism was anathema to the Irish World and was to be resisted and rejected at every opportunity. Part of this resistance included highlighting the machinations of Britain to influence American policy or to ingratiate itself with Americans. This Anglophobia as manifested in the Irish World certainly had its origins in Irish American hatred of England, but the paper also exploited the wariness of Americans toward Britain, its attempts to set its own course, define its own identity, and determine its own interests at home and abroad. Sensitive to the perils of exclusion in the United States as an immigrant group, and still insecure about their own status within society, Irish Americans strove to be of the nation and not just in it at the beginning of the twentieth century. A core aspect of a separate American identity was economic nationalism, and this is what the Irish World espoused and promoted in the face of increased pressure from Britain for free trade. Because the Democratic Party was associated with the policy of free trade, it was therefore regarded as being hand in glove with Britain during this period.

9.5. Irish World, April 22, 1905.

This linking of the Democrats with treacherous British influence on trade had its origins in the American Civil War and became associated with the administrations of Grover Cleveland in 1888 and in 1894 as the Republicans questioned his patriotism and accused him of being prepared to put Britain first in the matter of free trade.60 This led to a front-page cartoon of the “Cleveland Band” rehearsing a rendition of “God Save the Queen” under the conductor Grover Cleveland in December 1893, while the text stated that “Hail Columbia” and “The Star Spangled Banner” were “vulgar airs.”61 Based on the proposed reinstatement of Queen Lili‘uokalani to the throne in Hawaii by Cleveland in 1894, the cartoon’s underlying message emphasized Cleveland’s and the Democratic Party’s fascination with the British policy of free trade.62 This was much more openly conveyed in the 1904 election campaign as is clear from the Trojan horse and the gramophone cartoons. John Bull directs Belmont and Parker up the ladder into the wooden horse which bears the inscription “Made in England” on its base.63 The gramophone in the later cartoon belongs to John Bull and “his master’s voice” bellows free-trade orders at the Democratic candidate.64 Cheap English goods and manufactures carried by a delighted John Bull make their way into the United States in 1909 through the gap created in the tariff wall by the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act as the threat to American wages of the dismantling protection is made clear.65 This, then, is the broad and expansive environment in which the Irish World conveyed its views on protectionism encompassing opposition to free trade, the Democratic Party program, the influence of the British on American policy, and its support for the protection of labor and wages in the United States. This led the paper to support Republican candidates such as Roosevelt for the presidency in 1904.

John Bull and Japan

The signing of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance on January 20, 1902, was not marked by a cartoon in the Irish World, but the Russo-Japanese War, which began in February 1904, spawned a series of anti-Japanese cartoons published between September 1905 (after the war’s end) up to May 1913. The notion of a “yellow peril,” associated with Chinese migration to California in particular, was already prevalent in the United States, where white citizens saw Chinese emigrants as competitors for jobs. This “threat” had been exploited by Irishman and labor activist, Denis Kearney, in San Francisco in the 1870s and 1880s and led to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.66 The term was also commonly used in Europe, particularly by Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, to justify colonial acquisitions in China and to encourage Russia to curb the ambitions of Japan in the east. An editorial in the Irish World in September 1904 accused the Japanese of aiming for an overlordship of the Pacific if they were successful in the war against Russia and of “attempting to enact the role England once played in world affairs . . . [to] become the robber nation of the twentieth century.”67 The cartoon published in September of the following year, after Japan had won the war, juxtaposed the encouragement of the Japanese in their imperialist ambitions by John Bull through the Anglo-Japanese alliance and the threat of the “yellow peril” to the United States.68

9.6. Irish World, September 16, 1905.

This threat was compounded by the anger of the Japanese at what they perceived to be the unfair terms of the Treaty of Portsmouth, which was mediated by President Roosevelt.69 A rabble of Japanese identified by stereotypical eyes, dress, and hair cast rocks at Uncle Sam and carried threatening clubs, while in the background, more Japanese made their way with smoking torches toward him. The nature of the Japanese threat is interestingly portrayed as being almost medieval in this instance as the cartoonist appeared to suggest that in spite of their win over Russia, the Japanese and their “weapons” as portrayed here would be no match for the United States. Uncle Sam, holding the Russo-Japanese Treaty disinterestedly, walks away, but John Bull slyly peeps out from behind the wall holding the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. The word “foretaste” in the text of the cartoon suggested that the threat to the United States was only beginning from the Japanese and British together, and this was compounded by a front-page cartoon the following month showing John Bull and Japan, arm in arm clutching a club each on which was inscribed “the bully of the west” and “the bully of the east,” respectively.

Captioned “Looking for Trouble,” the absent Uncle Sam had only to be imagined in the middle, across the Atlantic from Britain and across the Pacific from Japan.70 While the smaller Japan personification in the cartoon could be explained by the smaller stature of the Japanese more generally, size in cartoons normally refers to a discrepancy in power relations.71 The continuing portrayal of Japan in the Irish World cartoons saw him as consistently smaller than John Bull, who was styled in various cartoons as his “mentor” in war,72 his “trainer” in fighting,73 and his “teacher” in the “school” of imperialist policy.74 The primacy of Britain in the evil canon of imperialism as seen by the Irish World was still unsurpassed, and other countries new to the pursuit of imperial acquisitions were still learning the trade perfected by Britain.

9.7. Irish World, October 7, 1905.

These cartoons echo those published in 1899 and in 1901 when McKinley stood accused by the Irish World of aping British imperialism in the Philippines. While McKinley himself was condemned in a cartoon published in February 1899 of throwing out all the key documents of the United States—including the Declaration of Independence, the Monroe Doctrine, and the Constitution, which he kicked into a fire—he was surrounded by objects reminiscent of the Roman Empire including a wastebasket shaped like the coliseum and a crown on a cushion with the title “Guliemus Primus Imperator.” Senator Hoar of Connecticut asked in January 1899 who would “haul down the flag” in the unconstitutional war, and the Irish World asked the same question as the country appeared to be drunk on “Imperial sec.”75 But the paper explicitly placed the United States as following Britain’s imperial trajectory in its front-page cartoon of May 4, 1901.

9.8. Irish World, May 4, 1901.

Uncle Sam waited in “Dr. Mars’s” waiting room, which sported framed pictures of land and sea battles on its walls, holding his ailment, the “Philippines.” John Bull emerged with a million-dollar bottle of medicine to cure his ailment, the “Boer War.” The text of the cartoon suggested that money was the only medicine to cure John Bull’s “robber constitution” and that it also might cure Uncle Sam, who was going the same route in the Philippines.76 This modeling of British imperialism, communicated by placing the figure of John Bull in recurring cartoons, invited condemnation of any country or leader who followed Britain’s lead and example, and this was a reliable trope in the cartoons published in the Irish World and drawn by a variety of cartoonists.

But there was more to the anti-Japanese viewpoint of the Irish World than Japan’s association with Britain. Although Cian McMahon maintains that the cartoons in the Irish World between 1870 and 1880 showed support for other nonwhite people around the world, this cannot be said for either the Japanese or the Chinese in the cartoons published in the paper at the beginning of the twentieth century.77 Anti-Japanese sentiment had been centered on California, where the majority of Japanese immigrants lived and the formation of the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League there in 1905 sought to emulate the successful Chinese Exclusion Acts of 1882 and 1892. Renamed the Asiatic Exclusion League in 1907, it campaigned to exclude Asian immigrants on the West Coast of America in order to protect white labor.78 Because of this hostility in the United States, Japanese immigrants began arriving in Canada, and by 1907, there were ten thousand immigrants in British Columbia. Aided by American labor activists, a new exclusion league was formed in Vancouver, and riots occurred there in September 1907.79 On September 21, 1907, the Irish World published a front-page cartoon featuring a Canadian carrying an exclusion flag in one hand and a club in the other, chasing a Japanese immigrant back into a rowboat. He is halted by John Bull with the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in his pocket, who protests that he is Japan’s friend.80 While the use of John Bull in this cartoon does convey the fact that Britain was the mother country of Canada, and Canada duly acted in accordance with British demands and wishes, it also encouraged condemnation for the British and Japanese position and support for the Canadian rioters and the exclusion league more broadly. The attitude of the paper to this supposed threat of Asian labor was further reinforced by a cartoon published on the eve of the 1912 presidential election when, once again, the Irish World supported Theodore Roosevelt, this time over the Democrat Woodrow Wilson.81 Because of its opposition to Wilson, the Irish World focused on Wilson’s support for the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act and printed a cartoon of the candidate outside a set of factories patting a small, stereotypical Chinese worker on the head paternalistically as an equally sized white worker to Wilson looked on.82 In spite of Wilson’s good record on labor, the Irish World evoked anti-Asian sentiment and racial bias in this cartoon to stoke the fear of labor competition among its readers. Wilson won the election.83

Conclusions

The rhetorical and visual strategy of the Irish World during the period 1890–1913 played to the notion that the United States was out in front, advanced industrially and economically, and that it could maintain and improve that position but only if it remained true to its core principles, ideals, and beliefs. Two of these core principles were isolationism and economic nationalism. Regarding itself as the “national” newspaper of Irish America in the United States, and carrying its editorial position squarely on the front page in the form of a political cartoon, the Irish World offered to its readers a “symbolic construction” of political and national identity.84 By presenting its political preferences for president, it sought to influence national political discourse and election outcomes by mobilizing its readers, not just in an ethnic network, but as a politically smart and effectual collective. Its visual commentary on national issues—whether the election of a president, the pursuit of imperialism, or the maintenance of protective tariffs—became part of a shared visual culture among Irish Americans that familiarized them with American political imperatives and communicated to its readers a significant lesson in American democracy—that their vote counted.

The support for the Republican Party, particularly on a national stage, is an interesting aspect of these cartoons. Colin Seymour-Ure, in his discussion of British cartoonists’ views of American politics, suggests that American politics are not primarily about ideology but about people, and that “presidential candidates (to oversimplify) put together electoral coalitions based on who they are, where they come from and what they have done.”85 The Irish World regarded the Democratic Party as too loose on the question of economic nationalism and as antilabor; although while that was true in Cleveland’s case, it was not in Wilson’s. They were both portrayed as Anglophiles. Its cartoons castigated William McKinley for his imperialist policy in spite of his good record on protection and the tariff that actually bore his name in 1900. Yet Theodore R. Roosevelt, who personified the “manly” arts of war, who had personally fought in Cuba, and who was undoubtedly imperialist, was supported on two occasions for the presidency by the paper, lauded as a supporter of labor, and feted as a separatist from Britain in spite of evidence of closer relations between the countries during his tenure. The possibility that personality politics was at play here rather than purely ideological considerations cannot be discounted. There were undoubtedly issues with McKinley’s imperialism and Cleveland’s free-trade policies that swayed the editorial position of the paper. But the generous leeway given to Roosevelt does suggest that he was liked as a person, whatever some of his beliefs. He was also from Manhattan, one of “their own,” and this might also be considered as appealing to the editor and the readers of the newspaper alike. The alignment of the paper with Republican Party planks more generally in the context of national policy marks a noteworthy and thought-provoking aspect of Irish American political affiliation.

There are elements of these political cartoons that capture contemporary convictions about race and the manner in which racial bias was expressed at the time. While the stereotypical caricatures of the Japanese were clearly drawn and readily identifiable in the cartoons, their alignment with the British through the iconic association with John Bull conflated the old Irish enemy and the possible new American one. Either way, the cartoons suggested, the Asians generally were internal competitors and external foes. The prevalence of these images on the front pages of the Irish World during this period suggests the utilization of the contemporary prejudices of Irish Americans in an American setting to inflect political outcomes. The environment of a rising America of innovation and progress is conveyed particularly effectively through taken-for-granted symbols such as the gramophone. The use of these contemporary, cultural references spoke to the idea of a rising, advanced America in comparison to the old world and the effort not to be contaminated especially by the British Empire. Condensing these prevailing perceptions into visual metaphors gives us an insight into readers’ biases and beliefs during this period.

Cartoons, according to Martin Rowson, are “serious journalism.”86 For the Irish World and its readers during 1890 to 1913, they provided a visual space where Irish Americans, who although potentially a powerful voting bloc, may still have been wary of the consequences of making their voices heard. But they could collude with the editor in challenging prevailing orthodoxies in a way that did not antagonize or confront native-born Americans or threaten their position within the status quo.87