Chapter 7

Building Melodies Using Motifs and Phrases

IN THIS CHAPTER

Exploring motifs

Exploring motifs

Building a melodic phrase

Building a melodic phrase

Avoiding boredom by varying the theme

Avoiding boredom by varying the theme

Changing up the rhythm

Changing up the rhythm

Truncating and expanding your melodies

Truncating and expanding your melodies

Exercising your phrase- and motif-building

Exercising your phrase- and motif-building

If you wrote melodies for the landscape drawings in Chapter 5, you may have noticed that some of the landscapes suggested repetitive themes and some did not. Some lent themselves to the use of a few short statements, whereas others seemed to demand more of a single, long narrative. Musical themes in composition are characterized by three main categories:

- Motif: A motif is the smallest form of melodic idea. It can be as short as two notes, like “cu coo,” or the first two notes of the theme from Star Wars.

- Melodic phrase: A melodic phrase can be up to four or more measures in length. Often a phrase is not really a complete musical idea. Phrases are usually separated by slight pauses, breaths, or rests. You can think of them as being similar to a single line of poetry. Several phrases make a period.

- Period: A period is a complete melodic idea. It can be 4, 8, 16, or even more measures long. It constitutes a musical completeness and can contain motifs or short or long phrases. When we refer to musical forms using letters (ABA, and so on), each letter usually represents a period.

You use these three kinds of melodic elements to build your compositions.

The Long and Short of Musical Themes: Motifs and Phrases

Often a composer’s entire body of work belies a tendency towards melodic long-windedness — using long, elaborately developed phrases — whereas other composers are more at home with shorter, choppier motifs.

Take a look at Maurice Ravel’s long and winding opening phrase in his famous one-movement orchestral piece, Boléro (Figure 7-1).

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 7-1: The first and most recognizable phrase, or theme, of Ravel’s Boléro.

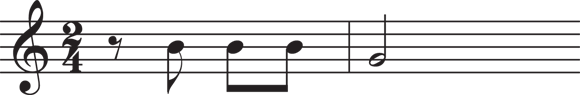

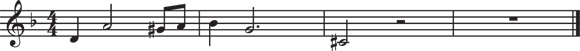

Now, compare Boléro to Figure 7-2: Beethoven’s four-note exclamatory motif in his Symphony No. 5 (Opus 67).

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 7-2: Da-da-da-DU — perhaps the shortest and most famous motif ever.

If you don’t know that one, you must have just crawled out from under the rock where you’ve been hiding for at least 200 years.

In the Ravel piece, he weaves his melody up and down for sixteen measures before he gets us to the end of a period, whereas Beethoven doesn’t even need four beats to state his motif. There is no question that both these compositions were successes for their composers, but their approaches are obviously very different. There are similarities as well: each repeats his theme and explores variations throughout the piece, giving the theme to different instruments and throwing it at the listener from various perspectives.

With Ravel, our fascination springs from seeing how far he can take a single, long theme while keeping it within a very repetitive rhythmic framework. Or is it seeing how far he can push a repeating rhythmic idea by leading us through it with his melodic narrative? The rhythm helps us hold our place as his long narrative expands. The long melody line keeps us from getting bored with the rhythm. Of course, the long, slow build-up of magnitude and intensity creates tension and keeps us interested, too.

Beethoven’s melodic repetitiveness holds our interest because we are fascinated and surprised by the variations he is able to bring to such a short, powerful motif, and the uses to which he puts such a simple idea. How many ways can you say, “I love you”?

It’s okay for your melodies to speak through short melodic ideas or long ones. The danger lies in losing the listeners’ interest. If your melody goes around the block a few times before reaching its destination, then maybe you should support it with a framework that allows your listeners to keep track of where they are, and where they are headed. A strong, repetitive, supporting rhythmic phrase or motif could be a good choice. And if your melodic ideas are short and sweet, it is important not to let them get boring. You have to get pretty inventive with the various uses of a short motif or phrase to make it hold interest for very long.

Remember that a motif is not particularly useful unless it is somewhat self-contained. If you imagine Beethoven’s Fifth without the fourth note, it would be very weak, and we probably wouldn’t be able to remember it very well. And Beethoven still needed more development around his motif in order to drive the idea home without driving the listener crazy. The whistling part of Ennio Morricone’s theme song for the movie The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly is another good example of a motif that is complete and sticks in your head as a result.

Similarly, a good melodic phrase is one that carves a place easily in a listener’s memory. If the phrase is too much like another one, it might be as easily forgotten as if it were too complicated to make sense of it. Walking the line of originality, accessibility, and familiarity is the trick to writing a lasting, memorable musical composition.

Of course, it is not uncommon to hear compositions in which a long melody line seems almost suspended in timelessness, like Pavane for Une Infante Defunte by Maurice Ravel. In this composition, the composer leads the listener through several different melodic periods that are almost complete enough and different enough from one another to have been the basis for three different compositions.

Building a Melodic Phrase

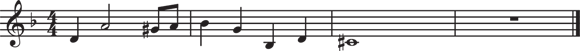

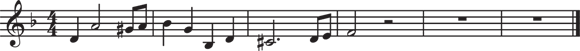

Let’s step back from motifs for a minute and examine phrases — the most basic building blocks of melody. How do we turn a couple of bars of melody into a musical composition? Consider the very simple melody line shown in Figure 7-3.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 7-3: A very straight-forward, hummable melody line can be your foundation.

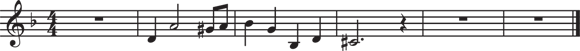

Now, let’s make the piece longer than the three measures it already is by employing repetition. Repetition is just like it sounds — repeating a musical theme in a piece of music, either immediately after the first time it’s played, or somewhere later on in the song.

Figure 7-4 shows what it looks like if you repeated the melody immediately after the first time it’s played.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 7-4: Repeating a melodic phrase reinforces it in the listener’s mind.

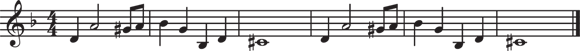

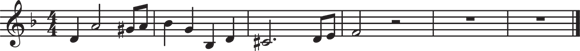

In Figure 7-5, we employ repetition again, this time adding a few additional phrases, sticking them in between the repeated parts.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 7-5: You can vary your use of repetition by adding other phrases to it as you repeat.

Another way to employ repetition is to have multiple instruments take turns playing the same phrase. You could give the music in Figure 7-6 to one instrument and that in Figure 7-7 to another, and the result would be a “round” kind of effect.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 7-6: Instrument number one could play this melody …

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 7-7: … While instrument number two plays this melody.

Another way to spread the phrase across the instrumentation would be to have the two instruments take turns “soloing,” as shown in Figures 7-8 and 7-9.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 7-8: Instrument number one plays the phrase while instrument number two rests …

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 7-9: … And instrument number two picks up where instrument number one leaves off.

Spicing It Up by Varying the Phrase

If you were a minstrel living in the Middle Ages, the information provided so far in this chapter would probably be all you would need to know to make your compositions minimally palatable to an audience. However, modern audiences want more from a composition than the same musical motifs and phrases repeated over and over.

Four ways to give them what they want would be to use the following tools:

- Rhythmic displacement

- Truncation

- Expansion

- Tonal displacement

These four methods are all ways to help make your short or long phrases expand into full-fledged compositions.

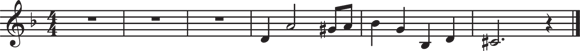

Rhythmic displacement

You can expand a rhythmic idea by changing the meter of the phrase. Rhythmic displacement is a favorite tool of jazz players. They pass around a theme, with the rhythm of each solo differing just enough to make it sound like they’re not all playing the same piece of music — even though they pretty much are.

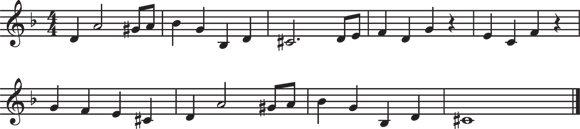

In the example shown in Figure 7-10, we’ve taken our original theme and expanded on it by changing the rhythm of the repeated theme.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 7-10: Here is our phrase after employing some good old rhythmic displacement.

By changing the values of some of the notes, we’ve changed the tempo and even the mood of the repeated phrase.

Truncation

When you truncate a verbal phrase, you cut it short (for example, the Dixie Chicks truncated their name to The Chicks in support of the Black Lives Matter movement). When you truncate in music, you’re cutting a repeated musical phrase short, as shown in Figure 7-11.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 7-11: Here is our phrase, this time with the first repeat truncated.

It’s completely up to you where and when you want to make the cut-off.

Expansion

Expansion is, of course, the opposite of truncation. In expansion, you add new material to the original phrase to make it last longer. You typically do this at the end of the phrase, as shown in Figure 7-12.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 7-12: Using expansion to fill out our phrase.

Expanded phrases are found at the end of many classical music pieces, including Beethoven’s “Moonlight” Sonata and, especially, his Symphony No. 5.

Tonal displacement

Tonal displacement is the technique of moving your motif to different notes within the appropriate scale while retaining the rhythm and contour of the phrase. Go back to Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, and notice that almost immediately after the statement of the first motif, old Ludwig repeats the motif, but with lower pitched notes. In fact, the bulk of this composition is an exercise in moving the same motif around tonally without much changing as far as rhythm and contour of the motif.

Exercises

Try out the following exercises to help you create longer, more complex melodies than covered in previous chapters.

- Write 16 measures of melody based on a three- or four-note motif.

- Write a 16-measure melody (period) in which there are no repeating motifs.

- Write a 16-measure melody (period) that contains the smaller repeating motifs of Exercise 1.

- Write 16 measures using small pieces from Exercise 2.

- Take one of the phrases resulting from the previous exercises and build on it, using repetition and rhythmic displacement.

- Take one of the phrases resulting from the previous exercises and build on it, using repetition and truncation.

- Take one of the phrases resulting from the previous exercises and build on it, using repetition and expansion.

- Move a motif around within a scale.

If you’re not familiar with Boléro, and you have a high tolerance for prurience, go out and rent the film 10, starring Dudley Moore, a heavily be-braided Bo Derek, and lots of jogging. You’ll be glad you did.

If you’re not familiar with Boléro, and you have a high tolerance for prurience, go out and rent the film 10, starring Dudley Moore, a heavily be-braided Bo Derek, and lots of jogging. You’ll be glad you did. It is all about mood, and few things are as tricky as sculpting time into a sense of temporal stasis where time itself seems to stand still.

It is all about mood, and few things are as tricky as sculpting time into a sense of temporal stasis where time itself seems to stand still.