‘Before I was diagnosed I was experiencing the effects of IBS almost daily, and it was causing me a lot of anxiety. I didn’t know much about IBS and was really worried that the symptoms I was experiencing might be the signs of something really serious. I was too scared to search online for answers as I was worried what it might say. It came as quite a relief to me when I was told what I had could be managed and was given advice about treatments I could use that would help.’

Kwilole

When you have IBS, it can feel that you’re completely at sea, awash in symptoms, mistrusting your own body and not knowing where to turn for help. The first step in finding the right treatment package is gaining a diagnosis. In this chapter we outline some of the tests a doctor might request in order to diagnose your symptoms. We also look at ways to help the doctor diagnose what’s going on, such as completing a symptom diary. Even people already diagnosed with IBS may find the material in this chapter useful as we also talk about procedures that may happen if they ever see a specialist gastroenterologist. Don’t worry, however, if you think you have IBS but haven’t had all of these procedures as you’ll only be asked to undergo them if your doctor thinks there’s good reason to – for example, to rule out other conditions that may explain the symptoms.

GP consultation

‘After a bad flare-up and years of struggling with symptoms I again went to see the doctor, a new doctor this time. I was at the end of my tether by this point. A junior doctor, he was very ‘thorough’. He asked me a long list of questions, examined my abdomen and conducted a series of blood tests and eventually concluded that I had IBS.’

Justin

The GP will see many people in her surgery who say they have gastrointestinal symptoms. To decide whether their symptoms are due to IBS or something else, she will ask for a history of the problem, which may include a number of questions along these lines:

- Have you had abdominal pain or bloating that seems to go away when you have a bowel movement?

- Does your abdominal pain or bloating seem to happen at the same time as periods of diarrhoea or constipation?

- Have you been passing more stools than you usually do?

The GP will also ask for a time frame for these symptoms, such as have they just started or have they been going on for some months? Some other questions that the GP may ask are:

- Have you needed to strain when you pass stools, when you didn’t previously?

- Have you been experiencing a sense of urgency or feeling you have not emptied your bowels properly that is new for you when going to the toilet?

- Do you have any hardness or tension in your abdomen?

- Are your symptoms worse after eating?

- Have you noticed any mucus from your back passage when you go to the toilet?

Many GPs will diagnose IBS based on the answers to these types of question and whether the symptoms fit into the ‘Rome criteria’ as mentioned in Chapter 1 (page 11). If you have only recently had these symptoms, sometimes the GP will tell you she suspects that you have IBS, but to monitor your symptoms (often with a symptom diary – see below in this chapter, page 48) to determine whether certain activities or foods aggravate your symptoms. She may offer you medication for diarrhoea or constipation, or an antidepressant. These are sometimes given as they have an analgesic (pain relieving) effect and also help with sleep. She may therefore give a prescription for antidepressants whether or not she thinks you are depressed.

If you are young and reasonably fit (apart from your IBS symptoms), the GP may ask you to come back in a few weeks if symptoms haven’t resolved. In order to be diagnosed with IBS, you need to have had the symptoms for around six months.

If you have been asked to monitor your symptoms and come back in a few weeks, then the best thing to do is to keep a symptom diary and to try to discover when your symptoms are worse and when they get better. Also, if you have been prescribed any medications, to take them as directed and note down whether or not they help your symptoms.

Your GP may ask you for a stool sample, a blood test and a breath test. She may also do a rectal examination to check for haemorrhoids (‘piles’).

Stool test

The stool sample will be checked for colour, consistency, amount, shape, odour and the presence of mucus. It may also be examined for parasites, hidden blood, fat, meat fibres, bile, white blood cells and sugars, which may help your doctor figure out why you’ve been having GI symptoms. The stool test can also help to rule out inflammatory bowel disease (see Chapter 1, page 7). A ‘stool culture’ may be performed too in order to look for bacteria.

Full blood count

A full blood count (FBC) looks at the following components of the blood:

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): This test will show whether you have any inflammation anywhere in the body. It can’t tell the GP where the inflammation is, but it’s just one piece of information that can be useful, along with other results, such as the ‘CRP’ below.

- C-reactive protein (CRP): This is a substance produced in the liver. It also shows whether or not there is inflammation in the body.

- White blood cell count: This can show whether you have an infection.

- Red blood cell count: This shows whether you have anaemia of one sort or another.

Rectal examination

Most people will find a rectal (back passage) examination embarrassing but your doctor or nurse will be aware of this. If for whatever reason (religious, cultural or simply personal preference) you would like the examination performed by someone who is the same sex as you, let the receptionist know before the day of your appointment for this. If you’ve not been given prior notice of this exam but would like a same-sex doctor or nurse to perform it, it is fine to ask for another appointment with an alternative practitioner. During the examination you will need to remove your clothing from the waist down and lie on your side on a medical table or couch with your knees pulled upwards to your chest. The doctor will first look for obvious abnormalities, like warts, rashes, haemorrhoids (‘piles’ – swollen blood vessels around the anus or rectum that can cause bleeding) or any skin tears near your back passage. Next the doctor will gently push a finger into your bottom and then further up your rectum. This can be uncomfortable and may cause some pain but the doctor will use lubrication (and gloves for hygiene) to make the procedure easier for you. The doctor might ask you to squeeze the muscles in your rectum so that she/he can see if they’re working properly. If you’re a man, the doctor might also perform a prostate examination at this time, which involves pressing on the prostate gland. This shouldn’t hurt but it may make you want to pass urine or feel a little tender. This entire procedure shouldn’t take more than five minutes and often considerably less, so while it’s not pleasant, it should be quick.

Antibody test for coeliac disease

People who have coeliac disease (sensitivity to wheat and other gluten-containing grains) have symptoms that resemble IBS (see Chapter 1, page 7). A blood test would let your GP know whether or not you have coeliac disease.

Breath tests

A breath test can tell whether you have bacterial overgrowth (see Chapter 9, page 137).

It can also show whether you are intolerant to lactose as this results in similar symptoms to those of IBS if you eat or drink anything with lactose in it. Lactose is a sugar found in dairy products, such as cow’s milk, butter, and cheese, and people who are lactose intolerant do not have enough of an important enzyme called lactase. If you have this problem, then a lactose-free diet will help you, and you may no longer be diagnosed as having IBS.

Diagnosis of food allergies

Skin-prick testing or blood test

A skin-prick test is a quick test to determine whether you are allergic to food allergens. The skin will be punctured on your arm, and a tiny bit of allergen will be introduced. If you are allergic, then a red spot will appear within a few minutes as a result of the release of ‘histamine’, a substance that is an important part of the immune response.

Sometimes a blood test will be taken and later analysed to see whether you have a reaction to the production of ‘immunoglobulin E’ (IgE) antibodies in reaction to certain foods. If you do have a reaction, then you will know you are allergic to these foods and can take steps to manage this problem (see Chapter 5, page 72).

Food challenges

Under close supervision, you will be given a small amount of the foods to which you suspect you are allergic, in order to see what happens. If you are allergic to the food, then you can be given treatment straight away to counter your allergic response. We discuss food allergies in more detail in Chapter 5.

Food intolerance and sensitivities

There are no mainstream diagnostic tests (i.e. tests that you can get from your GP) which can show you whether or not you are intolerant or sensitive to certain foods. However, a number of private clinics offer specialised testing which claims to identify trigger foods so you may want to consider visiting one such clinic. Please do bear in mind this form of testing can be quite expensive and there is not a great deal of independent research to support its use, although this may of course change in time once more research is carried out. However, you can use an exclusion, or elimination, diet to discover if you are sensitive or intolerant to particular foods and drinks. In Chapter 5 there is guidance on how to do this.

Further testing

If a member of your family has had certain types of cancer (bowel or ovarian), your GP may also want to run more tests on you. If you are middle-aged or older, it is also more likely you will be offered further tests to determine whether you have IBS or something more serious. This is because the likelihood of other illnesses, such as inflammatory bowel disease or bowel cancer, is higher in older people.

Whatever your age, you may have some ‘red flag’ symptoms that will prompt your GP to carry out more tests. These include:

- Weight loss that cannot be explained by any other cause, such as a change in diet or lifestyle

- Obvious swelling or a lump in your abdomen or back passage (rectum)

- Bleeding from your back passage (rectum)

- Anaemia (low red blood cell count).

If your GP decides you should have further tests, she will refer you to a gastroenterologist.

Procedures

If you’ve been referred to a specialist there are a number of procedures that you may be asked to undertake. There’s no point trying to hide the fact that these can be unpleasant. No one wants to experience intrusive medical procedures in intimate areas, but these will generally be uncomfortable at most, not painful, and the results will help your gastroenterologist decide the best course of action for your treatment, which can only be a positive thing in the long run.

Sigmoidoscopy

One of the first tests you might be offered is a sigmoidoscopy, which is a procedure that is carried out in the hospital or the GP’s surgery. It doesn’t require an overnight stay and you can usually go home soon after the test. This procedure involves a sigmoidoscope, which is a thin, flexible tube that has a small camera and light attached.

This is inserted into the rectum so that the gastroenterologist can investigate your lower bowel. This is to see if there are any polyps or signs of cancerous growths. Bowel polyps are small growths (usually less than 1 cm) that are not normally cancerous but may need to be removed to make sure they don’t turn into cancer. Polyps are very common – it is thought about 15-20% of people in the UK have them – and most people don’t notice them at all as they often don’t cause symptoms.

People don’t normally need sedatives for a sigmoidoscopy and the actual test only takes between 10-20 minutes. It might be uncomfortable (as you can imagine), but it shouldn’t be painful. The gastroenterologist will start by examining your rectum (see page 38). You’ll be asked to lie on your left side with your knees bent to make this easier. Once the sigmoidoscope has been gently inserted, carbon dioxide gas or air is pumped into the lower bowel which makes it expand. This makes it easier for the gastroenterologist to view the bowel wall with the instrument but may be a bit uncomfortable as you may feel like you need to pass wind or go to the toilet; this is completely normal and you shouldn’t feel embarrassed.

Your gastroenterologist will at this stage be looking at a video monitor where the pictures of your bowel are displayed. If she sees polyps she may want to remove them there and then and this shouldn’t cause you any pain. She may also want to take a biopsy which will be looked at later in the hospital laboratory.

It is best to rest at home after a sigmoidoscopy, but there is very little chance of significant side effects from this procedure. You may feel bloated for a few hours or have stomach cramps, but these should pass. If they do not, please tell your GP. If you’ve had polyps removed or if the gastroenterologist took a biopsy, you may experience some bleeding from the rectum. This should stop within a few days, but if the bleeding becomes heavy, please contact your GP and the hospital where the test was carried out.

Barium enema

If the sigmoidoscopy or routine blood tests are abnormal, you may be offered a barium enema. This procedure is unlikely to be painful, but it can be uncomfortable.

Before you have this procedure, you will be given a leaflet telling you what you should or should not eat, in order to ensure that your bowel is emptied; and to make extra sure this happens, you will also be asked to take laxatives.

You will be seen in the X-ray department of the hospital. Normally a needle will be inserted in your arm in order to be given mild sedation.

A milky substance (barium – a substance that shows up when X-rayed) is pumped up through your rectum and through to your colon. This contains air as well as the barium. Your bowel, and the passage of the barium through the bowel, can be seen as X-rays on a computer monitor.

The radiographer will later look at the images in detail, to determine whether anything unusual, like tumours or inflammation, is present. This means waiting a few days for the results.

If you have IBS, everything should show up as normal – which doesn’t mean ‘there’s nothing wrong with you’. There is something wrong, but at this point the diagnosis may still be uncertain.

Upper GI series

A barium swallow and meal involves swallowing a drink that contains barium (a substance which shows up on X-rays). The barium coats the inside of your throat, oesophagus (the pipe that goes from your mouth to your stomach), stomach and small bowel. This allows for clearer X-ray images.

You will have to refrain from eating for a few hours before the test. The doctors might tell you the barium drink is like a milk shake, and it does look like that, but unfortunately it doesn’t taste like one. Once you have drunk the chalk-like drink, after a short pause, the radiographer will take X-rays of the upper part of your gastrointestinal (GI) system. The barium meal moves down through your throat, oesophagus, stomach and small bowel; and the images are recorded. Later the radiographer will look at the images in detail in order to determine whether any tumours or ulcers are present in the upper part of the GI system.

Upper endoscopy

This is a procedure where an ‘endoscope’ will be used in order to look at the lining of your upper GI tract. The endoscope is a long flexible tube with a tiny camera attached. An anaesthetic will ensure that your throat is numb; the endoscope will be passed down your oesophagus and into your stomach and duodenum (the first section of your small bowel). You can choose to be sedated for this procedure. The doctor will be able to see any abnormalities in the upper GI tract.

Colonoscopy

‘For me the preparation for the colonoscopy was the worst part. This was because before the procedure I had to take some strong laxatives (which were provided by the hospital). This meant that I couldn’t go very far from a toilet for two days. There’s no avoiding this because your bowels have to be totally empty before the test. If you’re on any medication then your doctor may advise you to stop taking these before the procedure. I had to stop taking iron supplements because they make the inside of the bowel go black which would have meant the doctor would not have been able to see anything. I was told in advance that many patients have no memory of the colonoscopy procedure due to the sedative given.

‘The actual procedure wasn’t too bad. I had mine done as a day patient. I was given some trousers with a hole at the back to wear, and I was given some painkillers and a sedative. It started with me lying on my side and then at different points the doctor turned me over from side to side, but the sedative worked so well that I was only vaguely aware of what was happening. It’s difficult to really remember what it was like to have the colonoscopy. I remember the intravenous injection and then nothing much apart from seeing lots of bright colours swirling around like a kaleidoscope and the next thing that I knew was I was in the recovery room. The same thing happened when I had the endoscopy. Afterwards I was given time for the sedation to wear off and then went home (escorted – hospitals won’t let patients out alone after they’ve had sedation).’

Liz

Sometimes, especially if people are middle-aged or older, the GP will refer them to the clinic or hospital to have a colonoscopy, rather than having a barium enema and sigmoidoscopy. A colonoscopy is similar to a sigmoidoscopy, but in this procedure a device called a colonoscope is used. This instrument is longer than a sigmoidoscope and so can see inside the length of your bowel (large intestine) This enables the gastroenterologist to determine whether polyps or cancer are present anywhere in the length of the bowel. This test takes around 30–35 minutes to complete and you will be offered a sedative or painkiller to make sure you’re as comfortable as possible during the procedure. You will be asked to lie on your left-hand side so that the doctor can insert the colonoscope, or ‘endoscope’, into your back passage (rectum), with the aid of lubricant.

As with the sigmoidoscopy, some air will be pumped inside your bowel so that the colonoscope can pass through the bowel with ease, which might cause wind. This will feel strange but try not to worry about it; it is simply part of the procedure. Also like the sigmoidoscopy the doctor will view your bowel on a monitor and possibly take a biopsy or remove polyps. You won’t feel any pain however and you may not actually remember much about the procedure due to the effects of the sedative, as per Liz’s account above.

Aftercare is the same as for the sigmoidoscopy so keep an eye out for any excess bleeding or discomfort. But if you have had a sedative you will need to rest immediately afterwards to allow it to wear off; also, arrange for someone to collect you from the hospital. Don’t drive, drink alcohol, operate heavy machinery or make any important decisions for at least 24 hours after the procedure as sedative can impair your judgement and cognitive abilities. After 24 hours you should be back to normal and able to return to your daily activities.

Ultrasound

An ultrasound scanner is able to provide moving pictures of particular organs. You might have an abdominal scan and/or a pelvic scan. For the scans, you will be lying down. The sonographer (who performs the ultrasound) will put a gel over your abdomen and/or pelvis. She then moves a sensor around the appropriate areas, which produces pictures which she can see on a computer screen. You might also be able to look at the screen.

The actual procedure differs according to the type of scan. For some, you might have to drink water beforehand, so that your bladder is full when you have the scan. This is not a problem unless there is some delay at the hospital, and you have to wait a lot longer than expected – then you might have to go to the loo! If this happens, and you cannot stop mid-stream, then the appointment might need to be rescheduled.

For other types of scan, you might have to not eat anything for some while beforehand, or you might have to keep your bladder empty. You will be given all the appropriate instructions in advance of the appointment. None of these procedures is unpleasant or painful, and you will be able to go straight home afterwards.

Although the scan can’t diagnose IBS, it will be able to rule out other problems, such as gall stones, cysts and abscesses.

Working with your doctor

So far in this chapter we have looked in detail at the questions you are likely to be asked by your GP, the tests that you may have in primary care and the likely procedures you will undergo if you’re referred to a specialist. This may seem overwhelming or, on the other hand, you may feel frustrated if your doctor has not referred you for more tests. With a complex illness like IBS that may take time to diagnose, it’s important to try to develop a collaborative relationship with your GP. This is, of course, a two-way process and if you feel your GP isn’t taking your concerns and symptoms seriously, ask if any other doctor in the practice has a special interest in gastrointestinal disorders as s/he will have more up-to-date knowledge of IBS. (In Chapter 8 we will look at medical professionals’ views of IBS and how these can differ from patients’ ideas about their symptoms.)

There are a few ways to develop a collaborative relationship with the doctor which help her to make an accurate diagnosis:

- Keep a detailed symptom diary (below)

- Don’t expect a diagnosis straight away – IBS is diagnosed on the basis of symptoms and the exclusion of other diseases so this may take time; try to be patient even though this may be hard

- Be active in taking control of your condition – IBS is a complex disorder and as such you may need to use a combination of symptom-relief medications, stress-reduction techniques and other changes to your daily patterns and habits (which we will discuss in Chapters 4–7). This does not mean that you are to blame in any way at all for having IBS, rather that there are many things that you can do yourself to manage your symptoms.

Tracking symptoms with an IBS diary

‘Keep a regular journal of your triggers – whether it’s certain foods, a particular time of the month or nerve-wracking situations, it will all be useful in helping you manage the condition on an ongoing basis. Keeping a diary will make it really clear when and why IBS affects you personally.’

Nicola

In order to help identify trigger foods and daily stresses that may exacerbate your IBS, it is extremely useful to keep records of symptoms and activities in a personal IBS diary. A symptom diary for IBS differs from versions for other conditions as you need to pay particular attention to the nature and types of IBS symptoms you have and also to exactly what you’re eating. Many of us are quite unaware of what we eat and can be rather surprised when we look at it on paper. Also, trying to simply recall foods, drinks, symptoms and everyday stresses is not at all easy. Therefore, a detailed diary can help both you and your doctor identify any patterns in your IBS that will help healthcare professionals come up with an effective treatment plan.

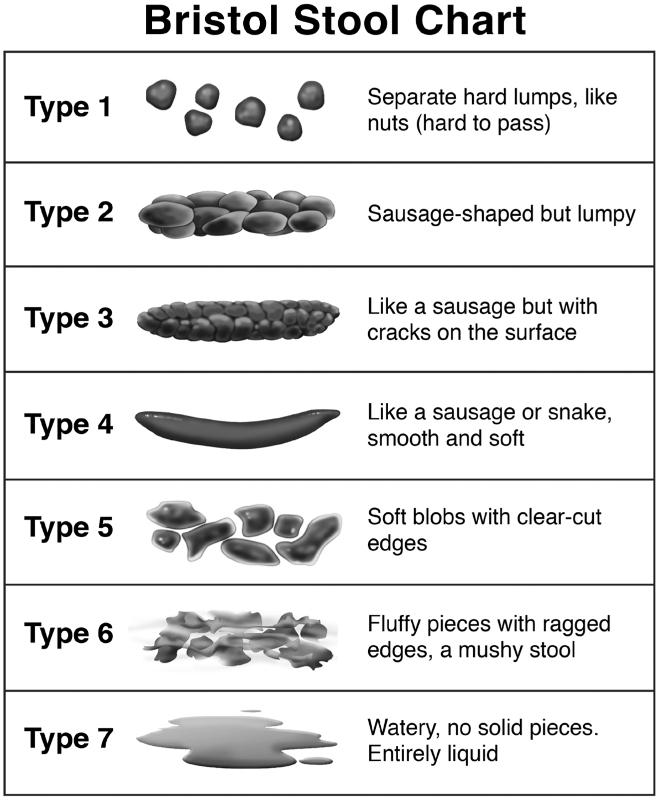

Bristol stool chart

Before we outline what an IBS diary should look like, you need to know how to identify your bowel movement type. This might sound unpleasant and embarrassing, but the characteristics of your bowel movements can provide important information about your gastrointestinal health, especially if your stools change over time.

The Bristol stool chart (Figure 2), based on the Bristol Stool Form Scale, was developed at the University Department of Medicine in Bristol’s Royal Infirmary by Dr Kenneth Heaton (now sadly deceased but he played a major part in helping scientists and doctors understand and be able to diagnose IBS). The chart contains seven different stool types that vary in size and shape, from small hard lumps (think rabbit poos) to completely liquid diarrhoea (see below).

Types 1 and 2 are indicative of constipation and difficult to pass. Types 3 and 4 show more healthy bowel movements and shouldn’t require straining (but it’s important to bear in mind that everyone is different and you can have any combination of sensations and stool type – what matters is what’s normal for you and if this suddenly changes). Types 5–7 are often accompanied by the urgent need to go to the toilet and suggest mild to severe diarrhoea. You can use these classifications in your IBS diary to help your doctor understand your individual bowel habits.

Figure 2 The Bristol Stool Chart – This is a useful tool in helping to identify types of bowel movements; this information can help doctors to diagnose IBS-like symptoms. (Copyright © 2006. Rome Foundation. All rights reserved.)

IBS symptom and food diary

There are numerous versions of IBS symptom diaries online, apps that can be downloaded on smartphones and tablets and paper-based methods that can be purchased, but of course you can simply use a paper and pen to construct a diary. The key areas to include are:

- Today’s date and day of the week – it doesn’t matter which day it starts on but including this somewhat obvious piece of information helps in case any of the pages get muddled up. Also, symptoms could follow a weekly pattern if there are any triggers that occur on specific days; for instance a coffee morning with friends or tense weekly meetings at work (even if you are unable to do these things do keep a record of the date as very small daily changes may be affecting the IBS).

- You can use a grid where rows are time points and columns are categories to note, as below in Figure 3, or simply use a different sheet of paper for each of the events.

To summarise the table on page 52, the categories you need to include in your IBS diary, or check are in the app or downloaded version that you want to use, are:

- bowel movement type (see stool chart above), whether you felt you hadn’t been able to pass all the faeces (known as an ‘incomplete evacuation’) or incontinence (having an accident)

- pain – for example, pain on either side of your abdomen, stomach cramping, lower intestinal cramping, tenderness (when the skin is pressed), rectal pain (note down whether this pain is sharp, dull, burning), other rectal pain such as the sensation of a hard object in the rectum or cramping in the rectum

- other GI symptoms – for example, burbulence, belching, passing wind; also describe any smell associated with the latter

- medication use – try to record the dose taken and the strength of tablets. Also include any herbal remedies, probiotics or prebiotics

- food and drink – it’s important here to be as detailed as possible and include everything you eat and drink. The doctor is not going to judge your diet in terms of healthy/unhealthy, just whether certain foods and beverages may be impacting on your IBS. The time and pattern are also important – for instance, in the example symptom diary above, our hypothetical person drank coffee on an empty stomach soon after waking. The reason for this is clear – she needed some ‘get up and go’ but was scared to eat anything before taking her children to school so had a caffeinated drink instead. The type of drink and also the delay in eating breakfast might be making her IBS symptoms worse, so noting down not just what food or drink but when and also why allows a healthcare professional to start to build a picture of your particular eating style and if there are any trigger foods/drinks

- feelings and stressors – write down how you’re feeling when you wake up and go to bed as this may indicate a sleep problem that you may want to discuss with your doctor. Also, include any feelings associated with your IBS (or not), such as frustration, fear of eating, drinking, travelling etc. Other things to include in this column are stressors, such as a difficult presentation at work, arguments, daily obligations (work, shopping, childcare, cooking, etc), and more significant issues such as physical injuries, caring responsibilities, relationship or money worries, moving house or bereavement.

Figure 3 Symptom and food diary – This diary can be used by both patients and doctors to identify any patterns or triggers that might be associated with IBS symptoms

You may also want to add an additional column or page to report exercise, symptoms of any other illnesses or infection and medications for these (for instance antibiotics can cause stomach upset), cigarettes or other smoking products, if you smoke, and your menstrual cycle if you’re a woman. Aim to complete your IBS diary for two to four weeks so that there is enough time to see patterns emerge.

As you can see, an IBS diary will hold a great deal of information and may feel time-consuming and intrusive. However, the more accurate you can be, the more clues you and your doctor will have to the underlying nature of your IBS. This can take out some of the guess work and experimentation with different treatments; hence you’ll be able to control your symptoms and get back to your life more quickly and also manage any subsequent flare-ups you may have in the future more effectively.

‘I’ve been struggling with IBS symptoms for years now. But it’s only recently, following diagnosis in November 2014, that I’ve started thinking about the problems I’ve had over the years as being related to IBS. Before that I wasn’t sure what I had. In fact, I probably thought constant bloating, stomach cramps, mucousy diarrhoea and the various other bowel-based treats that go hand-in-hand with IBS were somehow “normal”. Like everybody suffered the same problems all the time like I did.’

Justin

Summary

This chapter has included a lot of detail about what the doctor might ask in a consultation and some of the tests that might be performed either by a GP or a specialist. We have also outlined ways of gathering information to help doctors and other healthcare professionals to diagnose and then treat IBS (or other conditions if, after the consultations and tests, you are diagnosed with something else). This can seem overwhelming but it isn’t necessary to take it in all at once – diagnosis is a process and everyone will have their own personal journey.

The next chapter is the first of four that outline treatments and other strategies to help deal with the symptoms of IBS.