THE PSYCHOLOGY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF DREAMING

All human beings are also dream beings. Dreaming ties all mankind together.

JACK KEROUAC

The American Heritage Dictionary defines dream as a “succession of images, ideas, emotions, and sensations that occur involuntarily in the mind during certain stages of sleep.” The length of a dream, or a dreaming period, generally varies from a few seconds to around twenty to thirty minutes.1 Whether we remember them or not, everyone has around four or five dreaming periods a night. Dreaming is one of the basic activities that every human brain does. Just as the heart pumps blood and the stomach digests food, the brain dreams. In this chapter we’ll be reviewing what is known about the physical activity that takes place in the brain during sleep, what biological purpose dreams might serve, what psychological function they might have, and what language dreams speak to us in.

No one knows why we dream, or even why we need to sleep every night. According to psychologist William Moorcroft, author of Understanding Sleep and Dreaming, the function of sleep “persists as one of the most enduring and puzzling mysteries in science.”2 Nevertheless, we know that sleep is essential for our survival, and quite a bit is known about what happens in the brain while we sleep and dream. In 1879, German physiological psychologist Wilhelm Wundt speculated that while dreaming, the brains of sleeping people underwent marked changes in physiology. It turned out that he was correct.

THE NEUROSCIENCE OF SLEEP AND DREAMING

During the first half of the twentieth century electroencephalography (EEG), the recording of electrical activity (voltage fluctuations) in the brain using electrodes pasted along the scalp, was developed. This gave researchers a window inside the sleeping brain. Investigators discovered that sleep is not a continuous state; rather, it is a process composed of several distinct states of brain activity.

When we go to sleep each night, the states of activity that the brain passes through can be divided into two basic phases, REM and non-REM (NREM) sleep. REM stands for “rapid eye movements,” and this is a neurologically active phase of sleep in which our closed eyes move around quickly. This is a time when we’re most likely to be actively and vividly dreaming. NREM sleep is the more passive type of sleep, and it can be further divided into three distinct phases, known as N1, N2, and N3, which each have their own defining characteristics.

Everyone moves through a predictable pattern with these four basic types of sleep that repeat in cycles throughout each night. During the N1 stage of sleep, the brain is in a relaxed state of drowsiness, pulsing with alpha waves (8 to 13 Hz), and it begins to slow down to the rhythm of theta waves (4 to 7 Hz). During this stage of sleep our eyeballs move around slowly and we can be easily awakened. During the N2 stage of sleep the theta brain waves become punctuated by a specific type of brain wave known as a K-complex spindle, in which there are no eye movements during this stage. These spindles are fast, lasting only around half a second, and the waves register on an EEG monitor with a large, slow peak, followed by a small valley, which vibrates at a moderately fast frequency (12 to 14 Hz). Stage N3 sleep is characterized by the brain oscillating in slow delta waves (less than 4 Hz). There are no eye movements during this stage of deep sleep, and it is more difficult to awaken someone from this heavy state of slumber than any other stage of sleep. This is followed by REM sleep, which is, of course, characterized by rapid eye movements; the brain waves become fast, almost like in a waking state, and these are called “sawtooth waves.” This is the stage of sleep when we are almost always actively dreaming, although research and scientific evidence now suggests that we may be dreaming, or experiencing some type of mental activity, throughout our sleep.

There is currently no clear physiological indication that signals that a person is dreaming within the usual sleep laboratory measurements. In other words, there is no definitive way to physically measure or determine if someone is actually dreaming; self-reports are the only way to know for certain and these don’t always match up with the REM stage of sleep. That is, with one obvious exception: when a lucid dreamer can signal to researchers during sleep. Our ability to remember dream experiences after being awakened in a sleep laboratory is around 80 percent during REM sleep and 45 percent during NREM stages of sleep.3

Russian mathematician and esotericist P. D. Ouspensky (1878–1947) stated that careful observations of his mental states led him to believe that people are always dreaming.4 According to Ouspensky, our waking consciousness overshadows the ever-present dreams going on in our brains, just as the sun outshines the stars in the sky during the day, but the dreams are always there despite the fact that we are usually not aware of them and only remember them under certain conditions.

There may be something to Ouspensky’s idea. Sleep studies suggest that we may be dreaming all night long, and psychedelic experiences provide evidence that substantial unconscious psychological activity is always occurring below the threshold of awareness. In any case, lucid dreaming is characterized by gamma waves (20 to 50 Hz) during REM sleep, along with the active involvement of the prefrontal cortex, which performs executive functions in the brain. These brain wave cycles, characterized by N1, N2, N3, and REM, repeat throughout the night, with each of the four stages occurring about every ninety to 110 minutes. Throughout the night the periods of REM sleep grow longer and longer. This is why many lucid dreams happen to people during the latter stages of sleep, and why herbs, drugs, or supplements that promote dreaming or lucidity are most effective when taken at this time.

That’s the basic pattern of sleep that we all cycle through every night. However, making the leap from patterns of electrochemical brain activity to the wild world of dreams is no easy task. It is even more complicated when we ask ourselves how has modern living affected our dream life?

ELECTRIC LIGHTING AND HUMAN SLEEP PATTERNS

Few people are aware that before the Industrial Age and prior to the invention of artificial lighting, people (or at least Western Europeans) naturally had two periods of sleep each night, with two or three hours of calm wakefulness in between. Research by Virginia Tech history professor Roger Ekirch reveals that people didn’t always sleep in a single eight-hour period.5 Ekirch demonstrates how we used to sleep over a period of around twelve hours, during which time we would generally sleep for around three or four hours, then wake up for around two or three hours, then sleep again for another three or four hours.

References to these first and second sleep periods can be found in many works of literature and medicine that were written prior to the widespread use of artificial lighting. In The Canterbury Tales, Chaucer writes about a character who goes to bed after her “firste sleep.” Prior to electric lighting, a British physician wrote that the time between the “first sleep” and the “second sleep” was the best time for study and reflection.6 Additionally, research by psychiatrist Thomas A. Wehr at the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, Maryland, adds further support for this notion.7 Wehr conducted an experiment in which the subjects were deprived of electric light. At first, without the glowing distraction of light bulbs or electronic devices, the participants in the study slept through the night. However, after a while Wehr noticed that subjects began to wake up a little after midnight, lie awake for a couple of hours, and then drift back to sleep again. According to Wehr this period of “non-anxious wakefulness” possessed “an endocrinology all its own.”8 Wehr observed that during this period people had elevated levels of the pituitary hormone prolactin, which causes nursing mothers to lactate as well as being involved in a large number of other functions. He described this intervening period of wakefulness as an altered state of consciousness similar to meditation, which is correlated with lucid dreaming.

What Wehr observed in his sleep laboratory appears to be the same pattern of segmented sleep that Ekirch saw referenced in historical records and early works of literature. This period of several hours of wakefulness during the night is often described as peaceful, calm, and meditative. During this time, called the “watching period,” people are reported to have usually stayed in bed to contemplate their lives, converse with their partners, pray to their deity, make love, smoke tobacco, or simply enjoy their wandering states of altered consciousness. Also, according to Ekirch, it was of historical importance that during this period of calm wakefulness people “reflected on their dreams, a significant source of solace and self-awareness.”9

So how has this change in our sleeping patterns changed our dream life? No one really knows, but this change may have interfered with our awareness of our dreams and with our dream recall. Lucid dreams tend to occur in the later stages of sleep, especially after periods of waking oneself up before returning to sleep, so this more recent sleep pattern in humans may be making it more difficult for us to lucid dream.

When I interviewed Rick Strassman he suggested that artificial electric lighting could reduce the brain’s natural DMT production, which might be associated with dreaming. He told me, “With respect to the pineal [gland], pineal activity increases in darkness and during winter and decreases in increased light and in summer. Even relatively dim artificial light, indoors, has a suppressive effect on pineal function, and it may be that if generic pineal activity were related to DMT production, decreased activity through the aegis of increased ambient light during hours that were previously dark may have something to do with decreased normative DMT levels.”

Personally, I think that part of the reason I have so many lucid dreams—generally, several a month—is because as a writer I don’t have to follow a regimented sleep schedule. I wake up and go to sleep whenever I want to, and I often naturally sleep three to four hours twice during a twenty-four-hour period.

So nobody really knows how much artificial lighting has influenced our dream life. But then again, we hardly even have a clue as to why we need to dream every night to begin with.

WHAT IS THE BIOLOGICAL FUNCTION OF DREAMS?

In a meme that’s been floating around the Internet, one stick figure says to another, “Sometimes it seems bizarre to me that we take dreaming in stride.” “Are you coming to dinner?” the other stick figure asks. “Yeah, but first I’m gonna go comatose for a few hours, hallucinate vividly, and maybe suffer amnesia about the whole experience.” “Okay, cool,” the other stick figure replies. This simple cartoon highlights just how weird dreaming is, and how it is even stranger that we often don’t give it much thought.

Many psychologists and psychiatrists are taught that dreams are basically meaningless, mere byproducts of a sleeping brain, but some research suggests that dreaming may have a purpose, or, possibly, multiple purposes. According to influential neuroscientists J. Allan Hobson and Robert W. McCarley, dreams are the result of attempts by higher brain centers to “make sense” out the cortical stimulation created by lower brain “dream generators.”10 In other words, internal stimulation is randomly produced in the lower brain centers, while the higher brain centers use this as story material to shape our dreams. For this reason Hobson proposes that dream formation is an inherently creative process.

Some research suggests that higher brain centers play a more determining role in dream formation,11 while other research indicates that dreaming may serve a biological function. Psychologists Tore Nielsen and Philippe Stenstrom have demonstrated that “dreaming about newly learned materials enhances subsequent recall of that material.”12 Some neuroscientists think that sleeping is a way for the brain to clear out its daily accumulation of unneeded memories so that it can consolidate important memories together, and there is scientific evidence to support this.13 Additionally, REM sleep appears to facilitate brain development, as animals that are relatively immature at birth need to spend more time in this state.

One clue as to the function of dreams comes from that fact that most dreams are negatively biased and are about frightening, disturbing, shocking, or frustrating events. Most dreams are not sweet and pleasant, and in fact they tend to be reported as generally being more negative than waking life.14 For over forty years the late psychologist Calvin Hall collected more than fifty thousand dream accounts from college students. These revealed that the most common emotion experienced in dreams was anxiety, and that, in general, negative emotions were much more common than positive ones.15

People dream differently during different stages of their development, and there are also differences between how men and women dream. For example, men tend to report more acts of aggression in their dreams, and women’s dreams tend to have more characters in them.16 Also, male characters tend to predominate in men’s dreams by 67 percent, whereas the ratio between male and female figures in women’s dreams is more balanced.17

Another fact is that approximately 80 percent of all dreams are reported as being in color, although there is a considerable percentage of people who report they only dream in black and white. In studies where dreamers have been awakened and then asked to select colors from a chart that match those in their dreams, they most frequently chose soft pastel colors.18 Apparently, there is a certain area of the brain where our sense of color is processed, and if this area is damaged, then color disappears from perception in waking life, from dreams during sleep, and even from one’s memories.19

Other studies that may shed some light on the function of dreaming include those that incorporate a method whereby subjects wear glasses with vertically reversing lenses that have the effect of turning one’s visual field upside-down. After a few days, the subjects adjust to this topsy-turvy condition, and the world becomes right side up again with the prismatic glasses on. During the period of adaptation, the percentage of time spent in REM sleep escalates dramatically.20 This implies that dreaming may play a role in adjusting to altered modes of perception or sustained changes in one’s environment.

In any case, if the functions of sleep still remain largely mysterious, then dreams are even more puzzling. When researchers deprive people of just REM sleep, there are no obvious physical or psychological changes. However, it’s difficult to conduct REM-deprivation studies for longer than a week because the brain keeps trying to go into REM more and more each night, until the subject would need to be awakened too often to continue the research.

Also, as I mentioned earlier, additional research has shown that people not only dream during NREM sleep, they dream differently in REM and NREM sleep.21 It appears that our conscious minds are processing memories or are involved in some sort of mental production all night long, and people have reported dreams, and lucid dreams,22 in all stages of sleep. However, the types of dreams that people have during REM sleep tend to be more active, vivid, and anxiety- or fear-driven. Nightmares tend to happen during this stage of sleep. Meanwhile, NREM dreams are more often reported as pleasant, lacking anxiety, mundane, or boring. The primary differences between REM and NREM dreams is how one is represented in the dream. In NREM dreams we tend to be passive observers in past events, while in REM dreams we tend to play more active roles, and it is thought that these dreams are our brain’s models of the future.

Some evidence suggests that people can remain healthy without dreaming. An article that appeared in 2004 in the science journal Nature told about a seventy-three-year-old stroke patient who stopped dreaming after blood flow to her occipital lobe was disrupted.23 Prior to the stroke, the patient remembered three to four dreams a week, and then afterward she recalled none, although all of her other mental functions appeared normal. When she was tested in a sleep laboratory and awakened during periods of REM, she reported no dreams.

Some researchers think that trying to find the function of dreams is an unrealistic goal. Canadian psychologist Harry Hunt says, “I do not know if we will find true functions of dreaming, any more than we have been able to for human existence. A self-referential, self-transforming system like the human mind will evolve its uses as creatively and unpredictively as it evolves its structures.”24 Nonetheless, dreaming may serve numerous biological functions, and in this regard I think that anthropologist Charles Laughlin best sums it up when he states:

There really is no single function of dreaming—the functions of dreaming are manifold and depend upon the state of the brain and the time of dreaming. . . . Dreaming is the expression within the sensorium of neural models that may be developing, readjusting, and establishing connections among themselves or with other models, may be simulating or rehearsing waking experiences . . . may be working to solve problems and seek information, may be consolidating memories . . . may be expressing links between emotions and images . . . may be working through “day residue” issues, may be expressing repressed desires and emotions, may be dominated by traumatized imagery-emotion structures that remain thwarted in their development, and so forth. Dreams are, in other words, the symbolic expression in consciousness of whatever the cognitive/emotional/imaginal parts of the brain are on-about at the moment. Dream imagery may be a synesthetic experience of activities going on subconsciously elsewhere in the nervous system and the body. . . . The dream therefore is a stage upon which the brain portrays its ongoing activities (developmental, problem-solving, expression of repressed material, consolidation of memories, etc.) in often surrealistic plays.25

When I asked psychologist and dream expert Stanley Krippner what he thought the purpose of dreaming was, he summed up the general consensus among psychologists by saying, “It appears that . . . (REM) sleep, during which the most vivid dreams occur, served several adaptive purposes in the process of evolution: information storage, rehearsal of future activities, problem-solving, downloading of emotions, and completion of incomplete thoughts and feelings.” Therefore, as Krippner and Laughlin suggest, in trying to unravel the mystery of dreaming it might be helpful to look beyond its possible biological functions and speculate about what the psychological function of dreams might be.

Certainly one’s culture affects the contents of one’s dreams. Consider the following quote by psychology professor Roc Morin:

I’ve noticed population-specific trends as well. Violent nightmares are common in the gang-ridden border towns of Mexico and the war zone of eastern Ukraine. Scenes of nuclear war still haunt the “duckand-cover” generation in both the East and the West. Blessings by gods and goddesses are frequently reported in heavily religious India, whereas in more secular Western populations those same functions are often performed by celebrities. I’m not the first to document the link between culture and dream content. In one study, the dreams of Palestinian children in violent areas were found to feature more aggression and persecution than those of Palestinian children living in peaceful areas; in another, African American women were shown to have more dreams in which they are victims of circumstance or fate than Mexican American or Anglo American women.26

When I asked Stephen LaBerge about this he told me that he thought that dreaming helped us to survive evolutionarily because it allows our minds to safely experiment with new models of the world and ourselves. However, these “models” seem oddly encoded with symbolic messages that appear to have personal meaning, which can often be gleaned by careful reflection, and this commonly feels strangely like solving a puzzle. Before we discuss dream interpretation, let’s examine the following dream.

THE DEADLY GAZE OF THE FELINE DEITY

In 1997, I had the following (nonlucid) dream while visiting a friend in Herzliya, Israel:

I was standing in a large, spacious room, filled with a crowd of other people, where there was some kind of strange animal-worshiping ritual going on. There were these bizarre and deadly creatures there that everyone seemed to be watching with adoration and worshipful servitude. Everyone there had their attention focused on the front of the room, where there was a raised, ornately decorated platform. I was with a small child whom I loved and felt protective of, and held close to me. There was another child there, up in front of the room, who had this box with him. When the child opened the box, a long coiled snake began unraveling itself out from within. The huge snake slithered atop a large white stone throne. As the snake positioned itself onto the throne, it transformed into a powerful-looking, human-animal hybrid—a deity, with a woman’s body, a feline head, glowing eyes, and numerous arms or tentacles. The room was filled with intense fear, as everyone knew that this creature with the glowing eyes was going to take one of our lives at any moment. Suddenly, a bright light beam shot outward from the creature’s eyes, directly at someone in the room, and that person fell right to the ground. Immediately, everyone in the room rushed up to adore the creature. The creature’s eyes had stopped glowing, and they now looked like the hollow, empty sockets of a stone statue. I understood that the creature was harmless now, until its eyes filled up again. The room was aglow with a great sense of relief as everyone rejoiced, knowing that the danger was temporarily over.

This dream was quite vivid and disturbing. I awoke from it abruptly in a cold sweat. A few days afterward I flew to London, where I met with British biologist Rupert Sheldrake, with whom I was working on a number of research projects at the time. While leisurely walking around the lovely Hampstead Heath in London with Rupert, discussing our projects, I told him about my dream. Rupert seemed quite interested. He then told me that he had just (synchronistically) received a manuscript that week to review, Blood Rites: Origins and History of the Passions of War, by Barbara Ehrenreich. In her book Ehrenreich presents a theory for how the concept of animal and human sacrifice began in religious rituals during our prehistoric, evolutionary past, when humans were basically defenseless primates and were easy prey for wild cats. She suggests that we developed an oddly symbiotic relationship with these wild cats whereby we understood that they could eat one of us, but then afterward they would be satisfied and leave us alone. We also learned that they could provide for us and nourish us by allowing us to scavenge from their hunts of other animals.

So according to Ehrenreich, we learned to live with this reality by associating the loss of a member of our tribe with the survival of the tribe as a whole, and we thus created “blood rites,” or wars, to dramatize and validate our struggle in the food chain. This ancient association, buried deep in our collective mind, may be the foundation, Ehrenreich suggests, for our association with sacrifice in organized religion, our sense of territorial nationalism, and for the seemingly suicidal passion that many people have for war. According to Ehrenreich, wars are a form of ritual sacrifice that developed as a way to reenact our primal emotions as prey animals facing the terror of a ferocious and hungry beast.

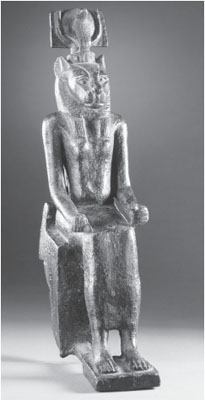

Hearing this theory after having my dream in Israel, the war-torn so-called Holy Land where the three major Western religions began with animal sacrifice, seemed to be a message from the collective unconscious about the origins of religion and war. Even more significantly, years later, while looking through a book on mythology, I found numerous depictions of Egyptian deities that were human-animal hybrids seated on thrones. Of particular interest were the goddesses Wadjet and Bastet. Wadjet is often depicted with a woman’s body and the head of a snake, usually an Egyptian cobra, and Bastet is shown with a woman’s body and a feline head that could be that of a cat, lion, lynx, or cheetah. Sometimes these deities are depicted in an opposite fashion, with animal bodies and human heads, and sometimes Wadjet and Bastet are depicted as a single deity, part woman, part lioness, and part cobra. Yes, this was the deadly deity in my dream. How did this Bastet/Wadjet hybrid deity find its way into my head?

This meaningful Middle Eastern dream didn’t feel personal; it felt as though I were witnessing an archetypal drama in what Carl Jung referred to as the collective unconscious. This term refers to a realm of prototypical information that underlies the collective dynamic of all human minds and is the source of common elements and figures, called archetypes, in myths, fairy tales, comic books, films, and dreams reported around the world. The dream that I had in Israel seemed symbolic and transpersonal, as if it were an impersonal message, like a television broadcast that I was tuning into, and it needed to be decoded. It seemed to be what some researchers would classify as a “big dream,” an unusually memorable dream that seems impersonal or initiatory, differentiating it from normal everyday dreams, which are usually about more mundane events in our personal lives. These big dreams call out strikingly for explanation, but many people believe that all dreams carry important messages. The story of how humans first came to understand the symbolic messages in dreams is lost in prehistory, but there is certainly a rich history of dream interpretation.

Fig. 2.1. Seated figurine of the goddess Wadjet-Bastet, with a lioness head and a cobra that represents Wadjet (courtesy Los Angeles County Museum of Art, www.lacma.org)

THE SECRET LANGUAGE OF DREAMS

According to Charles Laughlin, all societies have a “dreaming culture,” that is, every human society known on the planet has within it a group of people who consider dreams to be very important in their lives.27

Terence McKenna stressed how important language was in our mental modeling of reality. I love his example of an infant lying in a crib, looking out of the window at this magnificent and astonishing display of bright colors and furious movement, when the child’s mother points her finger at the psychedelic display and says the words that collapse that pure, pulsing sensory experience into the mechanical clucks of symbolic representation: “Oh honey, that’s just a bird.”

We also, obviously, do this with dreaming. Not only does Western culture tend to dismiss the importance, and any possible reality, of dreaming, the whole notion of a dream being a noun or a “thing” is completely deceptive. We routinely say that we “had a dream” and ask what “it” was about. But what we really experienced was a dreaming process while we slept, which we then try to piece together upon awakening—in our bed afterward, or within the dreaming process itself when dreaming lucidly.

The earliest notions that people had about dreams were ideas about how they were messages or revelations from deities or daemons. Records from early Egyptian and Sumerian cultures contain descriptions of dreams being sent to us by the gods; the same is true of stories in the Hebrew Bible, by the Greek poet Homer, in Grecian plays, and elsewhere in numerous historical documents. The Egyptian papyrus of Deral-Madineh, written around 1300 BCE, gives instructions on how to obtain a dream message from a god, and this appears to be the oldest manual in existence that was written to help people understand their dreams.

What all these early notions have in common is the idea that dreams come to us from somewhere other than ourselves, that they are messages sent to us by a higher intelligence or by divine or daemonic agency. Early notions of dreams also described their prophetic and healing powers.

The “dream temples” of Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine, on the island of Kos, were all the rage around 350 BCE. These temples operated as healing centers or early hospitals, where people suffering from various illnesses would come to sleep and to be healed by the power of divinely inspired dreams. Aristotle (384–322 BCE) was one of the first writers to attempt to study dreams in a systematic way, and he wrote three important treatises on the subject: De Somno et Vigilia (On Sleep and Dreams), De Insomnis (On Sleeping and Waking), and De Divinatione Per Somnum (On Divination Through Sleep). Aristotle revolutionarily said that dreams were not sent by gods and were not divine or supernatural in character, but rather follow the natural laws of the human mind. Dreams then became defined as “the mental activity of the sleeper insofar as he is asleep.”28 Aristotle pointed out that observations made while one is awake could carry over into one’s dreams, like the afterimages left behind from a bright object in our visual field. These memories from waking experience, Aristotle suggested, blend with our imagination while we’re asleep, and this creates the experience of dreaming. Aristotle also appears to be the first scientist to refer to lucid dreaming. In his treatise On Sleep and Dreams he writes, “Often when one is asleep, there is something in consciousness which declares that what then presents itself is but a dream.”29

Some of the first experimental investigations into the nature of dreams were carried out by French scholar and physician Louis Ferdinand Alfred Maury during the 1800s. Maury carried out a series of experiments wherein he was exposed to various forms of sensory stimuli while he was sleeping, and he then reported on how the stimulation was incorporated into his dreams. For example, he dreamed that he was being tortured when tickled under his nose with a feather by his assistant. How his assistant managed to do this without waking him up remains a mystery, but the understanding that environmental stimuli could become incorporated into our dreams becomes important to the discussion in chapter 6, where I review the electronic brain machines that can induce lucid dreaming.

Maury is probably most well known for having a very peculiar and inexplicably timed dream that he used to illustrate his notion that dreams are constructed in our minds much quicker than we generally think. He describes his famous “guillotine dream” as follows:

I was slightly indisposed and was lying in my room; my mother was near my bed. I am dreaming of the Terror. I am present at scenes of massacre; I appear before the Revolutionary Tribunal; I see Robespierre, Marat, Fouquier-Tinville, all the most villainous figures of this terrible epoch; I argue with them; at last, after many events which I remember only vaguely, I am judged, condemned to death, taken in a cart, amidst an enormous crowd, to the square of the Revolution; I ascend the scaffold; the executioner binds me to the fatal board, he pushes it, the knife falls; I feel my head being severed from the body; I awake seized by the most violent terror, and I feel on my neck the rod of my bed which had become suddenly detached and had fallen on my neck as would the knife of the guillotine. This happened in one instant, as my mother confirmed to me, and yet it was this external sensation that was taken by me for the starting point of the dream with a whole series of successive incidents. At the moment that I was struck, the memory of the terrible machine, the effect of which was so reproduced by the rod of the bed’s canopy, had awakened in me all the images of that epoch of which the guillotine was the symbol.30

How could this possibly have happened? Did the whole dream really happen in the flash of a second, and was the narrative actually created as Maury woke up? Or was Maury psychically aware that his bed was going to collapse in precisely that way on an unconscious level, and was this dream a form of precognition or a premonition? It’s a serious mystery, although as we’ll see in chapter 8, a form of psychic or precognitive awareness may actually be the more likely explanation.

P. D. Ouspensky attempts to explain this mystery by proposing that we develop the narrative of our dreams backward from the point of awakening, and not as they are actually occurring. According to Ouspensky, “The backward development of dreams means that when we awake[n], we awake[n] at the beginning of the dream and remember it as starting from this moment, that is, in the normal succession of events.”31 In other words, according to Ouspensky we formulate what we recall from our dream activity in the reverse order from which we generally think it has occured. However, reports and physiological evidence from lucid dreamers appear to contradict this notion, so the mystery remains as such.

On the cusp of the twentieth century, Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud, the “father of psychoanalysis,” put forth his theory of the unconscious with respect to dream interpretation. Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams, published in 1899 (subsequently revised at least eight times by the author), helped to create a scientific foundation for the notion of dream interpretation. Freud basically believed that all dreams are a form of wish fulfillment, and that they aren’t usually about what they appear to be on the surface. While few people would still agree with Freud’s position that all dreams represent a symbolic form of wish fulfillment, it seems that many initial lucid dreams are literal attempts to do so.

Freud asserted that dreams have symbolic or hidden meanings, that they act as a medium for the unconscious part of the mind (the part of the mind that cannot be known by the conscious mind, which includes socially unacceptable ideas, wishes, and desires, traumatic memories, and painful emotions that have been repressed) to communicate with the conscious aspect of our mind, i.e., the ego, which is nothing more than the organized part of our personality structure that functions like a miniature self. According to Freud, dreaming is the via regia, or “royal road” to the unconscious. In Freud’s model, deities and daemons were replaced by the unconscious as the organizer of dreams—a cloaked part of ourselves that contains the vast reservoir of our memories, wishes, fantasies, and unfulfilled desires, hidden from our conscious minds.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, a Spanish anatomist and neuroscientist who won the 1906 Nobel Prize for discovering neurons, thus founding modern neuroscience, was also a determined psychologist who believed that Freud’s ideas about dreaming were “collective lies.” After Freud’s book The Interpretation of Dreams was published, dreams soon became closely associated with the notion of “repressed desires” in psychiatric circles. Cajal set out to disprove Freud’s theory that every dream is the result of a repressed desire. Between 1918 and 1934, Cajal kept a journal of his dreams and collected the dreams of others, analyzing them and providing an alternative perspective to Freud’s notions. Thought lost for many years, this fascinating collection was published in 2014 under the Spanish title Los sueños de Santiago Ramón y Cajal (The Dreams of Santiago Ramón y Cajal). However, there was no mention of lucid dreaming in the English-translated excerpts that I read.32

Nevertheless, it appears that Freud was aware of lucid dreaming, although he didn’t have much to say about it and didn’t seem to understand its psychotherapeutic potential. In the 1909 second edition of The Interpretation of Dreams he added the following footnote: “There are some people who are quite clearly aware during the night that they are asleep and dreaming and who thus seem to possess the faculty of consciously directing their dreams. If for instance, the dreamer of this kind is dissatisfied with the turn taken by a dream, he can break it off without waking up and start it again in another direction, just as a popular dramatist may under pressure give his play a happier ending.”33

Freud was aware of the theories of French sinologist Marquis d’Hervey de Saint-Denys, who in 1867 published Les rêves et les moyens de les diriger (Dreams and How to Guide Them), about the author’s detailed experiments with lucid dreaming. But for whatever reason Freud was unable to obtain a copy (an English translation is now available). Freud also corresponded with Dutch psychiatrist Frederik van Eeden (1860–1932), who first used the English term lucid dreaming while delivering a scientific paper in 1913.

According to Jung, in his collected work on dreams from the Princeton Extract Series, what we learned from Freud was “that all the products of any dreaming state have something in common. First, they are variations on the complex, and second, they are only a kind of symbolic expression of the complex.”34 What’s important to note here is that although Freud and Jung, who were contemporaries, disagreed about many aspects of dreaming (and about psychology in general), Jung’s work built on the foundation that Freud had established by introducing important transpersonal concepts of interconnectivity between people and terms like synchronicity, archetype, and the collective unconscious. Jung suggested that dreams might originate from both personal and transpersonal sources, and his theory of the collective unconscious may help to explain why I had that dream in Israel about the deadly feline deity. Jung’s ideas, which express notions of meaningful coincidence, transcultural mental prototypes, and genetically shared aspects of our interconnected minds, developed out of his correspondence with quantum physicist and Nobel Prize–winner Wolfgang Pauli (1900–1958), and they provide valuable models for helping us understand the weird and wonderful world of dreams.

In describing the relationship between the collective unconscious, archetypes, and “big dreams,” Jung said:

Thus we speak on the one hand of a personal and on the other of a collective unconscious, which lies at a deeper level and is further removed from consciousness than the personal unconscious. The “big” or “meaningful” dreams come from this deeper level. They reveal their significance quite apart from the subjective impression they make by their plastic form, which often has a poetic force and beauty. Such dreams occur mostly during the critical phases of life, in early youth, puberty, at the onset of middle age (thirty-six to forty), and within sight of death.35

Although it appears that Jung never specifically addressed lucid dreaming, he did report personally experiencing conscious visions that sound a lot like lucid dreams, as do some of his descriptions of using a psychological technique that he developed to help people gain greater access to their unconscious, called “active imagination.” According to Jung, the active imagination is a meditation technique that can be used within psychotherapy to translate material from one’s unconscious mind into visual images or a story narrative, or personify them as separate entities. Jung’s approach became the foundation of many different dream interpretation systems as well as many popular beliefs about dreams, such as the notions that the unconscious mind is more knowledgeable than the conscious mind, and that by collecting sequential dreams in a series, they can be decoded as symbolic communications from the unconscious.

DO DREAMING MINDS AND SHAMANIC PLANT SPIRITS SPEAK THE SAME LANGUAGE?

Anyone who has ever experienced a shamanic journey on psilocybin mushrooms, peyote, San Pedro, iboga, or ayahuasca knows that when you close your eyes during the experience you will see a dazzling array of ever-shifting, continuously morphing images, patterns, and animated scenes. If you pay close attention to this closed-eye imagery it becomes clear that it isn’t random, but rather follows a meaningful pattern, as if the botanical intelligence is trying to communicate with us.

I suspect that the closed-eye visions that one sees on a shamanic journey with sacred plants are messages spoken to us in a symbolic language much like the language of dreams. These visions may constitute a kind of metalanguage in which the basic components of the language are animated scenes with complicated and emotionally charged imagery (akin to words), which symbolically communicate a massive amount of meaningful information at once when strung together before our eyes (like sentences). In any case, it can certainly seem this way. In Simon Powell’s wonderful book The Psilocybin Solution, this idea that magic mushrooms speak to us in the metalanguage of dreams and the unconscious is explored in great detail. This language seems ancient, protohuman—like it’s the voice of the biosphere, and it may be a universal system of communication used by other life forms. Speaking of other life forms, what about their dream lives—can they become lucid too?

DO OTHER ANIMALS HAVE LUCID DREAMS?

All animals sleep, in some form or another, and dreaming evolved long before our species arrived on the scene. A recent study reveals that bees learn and store information in their long-term memory while they sleep, like humans do when they dream—suggesting that even insects may dream.36 All terrestrial mammals enter the REM stage of sleep, accompanied by (at least partial) bodily paralysis, and many biologists believe that animals are dreaming when this occurs. Bodily paralysis presumably occurs during REM sleep so that we don’t act out the behaviors in our dreams. All voluntary muscles in the body are immobilized during REM sleep by the release of certain chemicals in the brain.

Studies conducted with animals in which the natural effects of sleep paralysis are neurochemically blocked show that animals exhibit exploratory or other behaviors while in REM sleep. It appears that they are acting out their dreams, which gives us a unique window into the minds of dreaming animals. With humans there’s a brain disorder called REM behavior disorder, in which people do the same thing. Oftentimes people who suffer from this disorder need to sleep alone in a padded room with no sharp edges.

To be conscious of one’s immobilized body during a state of sleep paralysis is often quite frightening for most people, although it’s really harmless. In fact, states of conscious sleep paralysis can actually be valuable springboards for lucid dreams or out-of-body experiences provided one can overcome the inherent sense of fear that naturally comes with this state (a subject we’ll explore further in chapter 9). Curiously, it appears that the body is in an even deeper state of sleep paralysis when lucid dreaming than when nonlucid dreaming. A 1986 study done at the University of Texas reports that the “Hofmann reflex” is more depressed during lucid dreams than nonlucid ones.37 The Hofmann reflex is produced by stimulating a nerve located behind the knee, the posterior tribial nerve. A response to this stimulation is a contraction of the soleus muscle in the calf, which extends and rotates the foot. The study found that this reflex was more suppressed during lucid REM sleep than during any other stage of sleep or wakefulness, including nonlucid REM sleep. It’s almost as though our brain recognizes when we’re lucid dreaming and physiologically compensates.

The largest amount of REM sleep known in any animal is found in the Australian platypus, which sometimes sleeps for as long as fourteen hours a day. But marine mammals and birds are different, and more mysterious. Birds only spend a tiny amount of time in REM sleep, and with marine mammals a complete absence of REM sleep is usually observed. Only in the case of one species of oceanic dolphin, i.e., the pilot whale, has there been measured a negligible amount of REM sleep.38 However, what’s most interesting is that dolphins, porpoises, whales, and birds sleep one brain hemisphere at a time, i.e., half of their brain sleeps while the other half stays awake, and then they switch. This ability to sleep with one half of the brain while the other half remains alert is called unihemispheric slow-wave sleep (USWS).

So one has to wonder, if dolphins and whales don’t experience much or any REM sleep, do they dream? As I discussed, humans will persistently increase their periods of REM sleep if deprived of it, so it appears to serve an important biological function, whatever it is. We also know from sleep studies that people report dreaming during non-REM stages of sleep as well; it just appears to be most consistently active and vivid during REM sleep. So dolphins may experience dreamlike consciousness during these stages of sleep too. In fact, some dream researchers speculate that lucid dreaming is a hybrid state of consciousness in which one part of the brain is awake while the rest of it is asleep. This hybrid asleep/awake state would be the norm for dolphins and whales. Even though there’s only the tiniest trace recordings of dolphins ever entering REM sleep, it seems that the hybrid states of consciousness resulting from their unihemispheric sleep patterns would be biologically ideal for lucid dreaming.

In any case, though it might be difficult to tell if dolphins dream or not, I’m confident that with time, cutting-edge dolphin researchers like Diana Reiss, author of The Dolphin in the Mirror, will figure out how to communicate with them well enough so they can tell us themselves. I suspect that they do dream, in some way that’s different than we do, and I wonder if they can form a hybrid state of awareness where they know when they’re dreaming and can influence what happens. It might be tricky to determine whether dolphins lucid dream by measuring their brain waves while they’re asleep. For the most part, this can be done in humans when gamma brain waves are observed in the prefrontal cortex during REM sleep.

As mentioned earlier, the biological function of dreaming may be to assist with the brain’s information processing and long-term memory storage, and it may have an additional psychological function, as a way for different portions of our mind to communicate with one another. But might dreaming have an even higher function?

DREAMING AND CREATIVITY

Dreams are creative by their very nature in that they produce a novel organization of experiences. Dreaming, or REM sleep, has been positively correlated with creativity, according to a study conducted by psychologist Sara Mednick and others.39 In Mednick’s study, people who took naps with REM sleep performed better on creativity-oriented word problems. According to Mednick, dreaming helped people combine ideas in new ways. Other studies suggest that people with high scores on creativity tests tend to recall more dreams.40 Additional evidence suggests that creative solutions to problems encountered while awake may be worked out or facilitated during sleep, whether or not a dream is involved. In one study in which subjects were given tasks with hidden rules, those who were allowed to sleep beforehand reached solutions faster than those who were not given the opportunity to sleep.41

Many people have had the experience of struggling to find the solution to a problem, only to go to sleep and then wake up the next morning (or in the middle of the night) with the answer fresh in their minds, as though their brains had been ceaselessly working all night on the problem. It’s not uncommon for the solution to a problem to simply require a creative association or a new perspective on one’s current knowledge, which is why dreaming can be so helpful. It’s also widely acknowledged that many creative artistic ideas, mathematical and scientific discoveries, and inventions have come to accomplished people through their dreams, both lucid and nonlucid. History overflows with stories of creative inspiration sprouting from dreams: Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein, the tune for Paul McCartney’s song “Yesterday,”*10 Keith Richards’ riff for the Rolling Stone’s song “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction,” Otto Loewi’s understanding of the chemical transmission of nerve impulses, Friedrich August Kekule’s discovery of the structure of the benzene molecule, Dmitri Mendeleev’s organization of the basic chemical elements into the periodic table, and Elias Howe’s invention of the sewing machine.

In Howe’s famous dream (or nightmare) that led to the invention of the sewing machine in 1845, he was fleeing cannibals in the jungles of Africa. He was captured by the cannibals, and as they tried to boil him alive they kept poking him with spears that had holes in their points. Upon awakening, Howe realized that the secret to making his sewing-machine idea workable was to move the thread transport hole up to the point of the needle—unlike a handheld needle, where the hole is on the base. This dream literally helped usher in the industrial revolution by making the mechanical production of clothing possible.

This dream also illustrates Jung’s notion of how one’s “shadow” can have a beneficial, creativity-enhancing aspect. According to Jung, the shadow is the dark and negative unconscious part of our personality that we lack identification with. The creative solution to Howe’s technical problem about how to thread the needle of a sewing machine literally arrived in the hands of fierce and frightening cannibals!

We can all be grateful for a dream that made navigating the Internet possible. Larry Page, the cofounder of Google, attributes his inspiration for developing the Internet search engine to a dream. After waking up from a dream, Page reported wondering, What if we could download the whole Web and just keep the links . . . ?”42 This was the inspiration for creating an invaluable tool that could quickly and effectively search through all human knowledge, thus radically changing the dynamics of human civilization.

Perhaps the most well-known example of how a dream can profoundly change the world comes from Mahatma Gandhi. Anthropologist Charles Laughlin writes:

There is perhaps no more famous example of how problem solving in a dream can impact cultural change than that of the dream-inception of Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent resistance to the British raj in India. When the imperialist legislature passed the restrictive Rowlatt Acts after the First World War, Gandhi cast about for an adequate response. He records in his autobiography . . . that: “The idea came to me last night in a dream that we should call upon the country to call a general [hunger strike].” His idea was implemented leading to the non-violent independence movement that came to fruition in 1947.43

In a study designed to explore the relationship between dreams and creative problem solving, mathematician M. E. Maillet sent out questionnaires to other mathematicians asking them if any dreams ever helped them to solve a mathematical problem.44 Out of the eighty replies he received, eight of the respondents reported that the beginning of solutions had occurred in dreams, and fifteen reported that they had awakened with partial or complete answers to mathematical problems, even though they did not recall dreaming about them.

For a comprehensive survey of how dreams have affected the creativity and problem-solving abilities of many scientists, artists, actors, writers, poets, and musicians throughout history, see Deirdre Barrett’s wonderful book The Committee of Sleep, where a treasure chest of these anecdotes are described, as well as the results from experimental research into sleep and creativity. Perhaps less well known is the specific influence that lucid dreams have had on creativity. For example, Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stevenson, author of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, said that he was “consciously making stories . . . whether awake or asleep.”45 According to Stevenson, he would sometimes wake himself up from lucid dreams when he had a good idea, to write it down before it was forgotten.

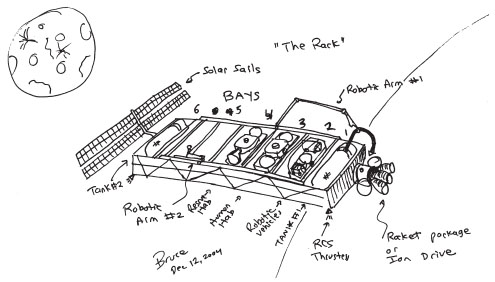

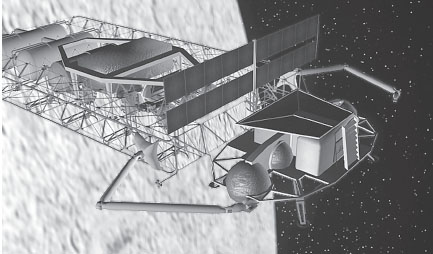

Bruce Damer, a scientist and mission visualization team leader for NASA, related to me one incident in which he used lucid dreaming to help him develop a specific mission for a NASA-funded study. Damer had a ten-year history of mission simulation and design, including the design of human missions to asteroids, rovers on Mars and the moon, and space shuttle and space station missions. He was tasked by Raytheon, the aerospace company, to support innovative ideas for the construction of a manned base on the moon. This was a difficult intellectual challenge, as it’s unlikely that astronauts could spend enough time on the moon to accomplish such a task, and build the base by hand, due to radiation and a number of other factors. Damer told me that in this case he spent months “preloading” into his mind the necessary information to solve this tricky technological problem, and then he “deliberately induced a visionary, lucid-dreaming experience from his own endogenous brain chemistry.” Damer also told me that he has used these natural mind-altering techniques to develop his ideas about models for how life might have begun46 and for developing mathematical representations of how the universe may operate. He described his lucid dream about the moon-base construction technique to me:

So I was in the process of waking up, and there it was, right in front of me—this whole vibrant world including the robotic spacecraft. I still had my eyes closed, but I knew I was in a lucid-dreaming state. My consciousness had awakened into the dream, and there it was, the rack with the robotics in it—all populated and functioning. I could see how it was constructed, how it was moved to lunar orbit, and how the robots went down and started building the base under remote control from Earth. I strove to stay with it because it was showing me the whole function. I reached for a pen and paper on my bedside table and started to draw what I saw. Then, immediately, I knew that I was being disconnected from the lucid dream. But I tried to hold on to the vision and continued drawing so I could capture it all. This concept went on to being rendered as a full CAD model in computer graphics and was included in the study for Raytheon, went off to NASA headquarters, and was shown at a major conference. So that’s one of my projects that emerged out of lucid dreaming, one form of my endogenous practice.

Fig. 2.2. Drawing by Bruce Damer, from his lucid dream (courtesy of Bruce Damer, NASA, and Raytheon)

Fig 2.3. Representation of the model for the NASA project that Damer designed via lucid dreaming (courtesy of Bruce Damer, NASA, and Raytheon)

It’s strangely ironic that lucid dreaming is often characterized in the popular media as dream control, because it can actually be such a valuable aid to the creative process by providing one with novel and original content. British lucid-dream researcher and novelist Clare Johnson was the first person to carry out doctoral research into lucid dreaming as an aid to the creative writing process, and she’s used it artistically herself in writing two novels, Breathing in Colour and Dreamrunner (as “Clare Jay”). Johnson identifies the primary qualities of lucid dreaming that can be used in the creative process as “rational thought, ability to recall preset tasks, heightened perception, conscious attention, detailed dream recall, dream control, lucid suspension or the ‘void,’ meditative states, and non-dual states.”47

Johnson studied twenty-five lucid dreamers for her doctoral dissertation, twenty of whom used creativity professionally in their careers— fifteen were writers and five were visual artists. She reported that the writers found lucid dreaming could provide assistance in overcoming obstacles, coming up with story ideas, and contributing to plot development; the visual artists also reported enhanced creativity by utilizing lucid dreaming.48

According to Johnson, “The dreaming mind itself could be considered to be a type of creative genius, with its spontaneous manifestation of imagery and its tendencies to original analogies.”49 When I interviewed her for this book, I asked her about the relationship between lucid dreaming and the creative process. Her response:

Dreaming is itself a creative process: the dream is thought-responsive and translates emotions instantaneously into imagery and personalized archetypes. In lucid dreams we can observe and influence this spontaneous creativity while it is happening. Just watching our “dream film” and seeing how it responds to our thoughts and emotions is a stimulating artistic resource. When lucid we can ask the dream for inspiration with a specific project, ask to be shown “something never created before,” or work on improving a physical skill like kickboxing or juggling.

Fig. 2.4. Lucid-dream researcher Dr. Clare Johnson (photo by Markus Feldmann)

Johnson suggests asking the lucid dream for creative inspiration. On her Facebook page she says, “Ask to see ‘something amazing’ when you next get lucid in a dream—great inspiration for art!” So I tried this in a lucid dream of my own, with the following results:

I was walking through a large warehouse or department store when I became lucid. There were no people around—just boxes piled high and what looked like store items or interesting sculptures or furniture. I was thrilled to be lucid again and quickly tried to think of what to do. I raised my head and began speaking to the spirit of the dream itself. As I was walking through the dream department-store warehouse, I said, “Astonish me!” The response came in my environment: the imagery got more vivid, more detailed, Gothic, and stranger. In particular, a huge chandelier above my head grew all these detailed octopuslike tentacles and ornately designed structures that were growing and morphing.

Artist and writer Daniel Love has a novel approach to tapping in to the creativity of lucid dreams, which I found inspiring:

The . . . technique I used to inspire my own artistic creativity was something I called “fractal dreaming.” . . . Once lucid, I would seek out the dream version of my already-painted artwork (or sometimes that of my favorite artists). Once found, I would use these paintings as “windows” into other “dimensions” of the dream world, jumping through the painting itself with the intention of entering the world within the painting. More often than not, this would be successful, with incredibly mixed results. Sometimes, the dream scene would shift to something seemingly unrelated to the painting, while other times I would find myself in a far more surreal dream landscape based on the artwork itself. . . . Whatever the result, I would then seek out a scene within this new landscape, something that I believed would make an interesting painting. Once again, when I had found what I needed, I would examine and commit this image to memory, ready to record it once I awoke.50

Visionary artist Dustyn Lucas does extraordinary psychedelic paintings that he says are almost all inspired by his lucid dreams. He writes:

My work nowadays comes almost entirely from a lucid-dream state. I memorize the images I see; balancing on the edge of dream and reality to sketch them as I wake. From that sketch I work with oils to bring the painting forth, keeping it as close to the original dream image as possible. In this way I feel that my paintings can resonate with the viewer in a deeper place, awakening and pulling up long forgotten emotions and ideas from the waters of the subconscious.51

Musician Pete Casale describes composing a piano piece called “Lucid” during a lucid dream:

While making my short video on lucid dreaming for . . . [the] web-site World-of-Lucid-Dreaming.com I needed a nice piece of music I could use without getting sued. I started by writing a kind of clunky piano piece in a hurried kind of way, but then I got tired so I went to bed. The next morning, before waking up, I had a small lucid dream during which I decided to compose a song on a piano made out of pure energy and light. That’s right, this song was written while I was asleep. It was actually about ten times as long but I couldn’t remember all of it. After I woke up, I hopped on the piano and started working out how to play the song, and I established as much of it as I could remember.52

I corresponded with someone online who also described playing a musical instrument in his dreams. It seems that you may have more success with one type of musical instrument than with another, as Steven Nelson writes:

Last night I had a [lucid] dream where I was trying to play a piano for some people but I couldn’t get a single good note out of it. They seemed disappointed so I pulled out my harmonica and started playing some gypsy-blues type music and it was effortless. All I had to do was think of a note and I could play it. I could even change to any key I wanted even though it was a diatonic harmonica. I wish the dream would have lasted longer because I could write songs like that for hours.

Clare Johnson appears to have had something akin to a shamanic experience in her lucid dreams; she describes seeing flowers that have watching eyes and entering into a bodiless void. In one lucid dream, Johnson looked at a reflection of her dream self in a dream mirror and saw miniature planets in her dream eyes. In this context, I thought that it was especially interesting that Johnson had her first experience of synesthesia in a lucid dream.

BLURRING BOUNDARIES BETWEEN THE SENSES

Synesthesia is a neurological condition in which the boundaries between the senses blur together so that when one sensory modality is stimulated, this evokes sensations in another. This naturally occurs in around 4 percent of the population—known as synesthetes—in some form or another, and it is commonly described in accounts where people “see” music or “taste” colors. Computer programs that display shifting patterns that morph, dance, and flash to the sound of music mimic the synesthetic effect of “seeing” music. Musical notes may also evoke particular taste sensations for someone experiencing synesthesia. A C sharp might taste minty, an F minor sweet. So for those of us unable to experience synesthesia, we can only imagine what kind of a tasty experience a good concert must be! Touch may evoke the perception of both colors and shapes, and some people with synesthesia say that acupressure, acupuncture, and massage can provide a corresponding visual experience.

Several studies show that synesthetes are more likely to engage in creative activities. Although this condition occurs naturally in some people, many people also commonly experience synesthesia during shamanic journeys or while under the influence of psychedelic drugs or plants. (Interestingly, most of the scientific articles about psychedelics list synesthesia as one of its possible effects, yet articles about the actual medical condition rarely reference the fact that psychedelics can often mimic it.)

Novelist Clare Johnson describes tactile sensations as “tasting like porridge” in a lucid dream in which she deliberately attempted to experience synesthesia when touching a wall.53 When I asked her about her experience with synesthesia, she told me, “Over time, I taught myself to experience synesthetic perceptions at will in my lucid dreams. This helped me to understand the way synesthetes experience the world and resulted in some of the freest creative writing I’ve done, multisensory and strange.”

Synesthesia may not only help foster artistic creation, it may also allow for new or previously unrecognized forms of artistic expression to emerge. Ayahuasca, the shamanic jungle juice from the Amazon, often produces synesthetic experiences. When I interviewed Terence McKenna, he had this to say about the experience:

When ingested . . . [ayahuasca] allows one to see sound, so that one can use the voice to produce, not musical compositions, but pictorial and visual compositions. . . . This is actually being done by shamans in the Amazon. The songs they sing sound as they do in order to look a certain way. They are not musical compositions as we’re used to thinking of them. They’re pictorial art that is caused by audio signals.

Magic mushrooms often produce similar sensory-blurring experiences. Research with psilocybin showed that this active component of the magic mushroom can cause the brain to become hyperconnected, allowing for increased communication between different regions of the brain.54

In the last chapter we discussed how some research with psilocybin shows that it decreases brain activity, and this remains true, although additional research has demonstrated that upon receiving psilocybin the brain also reorganizes connections and links together previously unconnected regions of the brain. These connections do not appear to be random, but rather are quite organized and stable, lasting for the duration of the drug’s influence, and then returning to normal. Interestingly, the researchers involved in this study stated, “We can speculate on the implications of such an organization. One possible by-product of this greater communication across the whole brain is the phenomenon of synesthesia, which is often reported in conjunction with the psychedelic state.”55

Something similar may be going on when we’re lucid dreaming, in that the experience may be linking together previously unconnected regions of the mind. In his book Are You Dreaming? author Daniel Love suggests that the heightened sensory experiences reported by many people in lucid dreams, along with the potential for synesthesia, are due to the more direct fashion that we experience sensory information in lucid dreams. Love writes, “Rather than being the end result of a process, starting with the processing of input from our genuine physical senses, our experience of these things in dreams all occur in the immediacy of our own brains. There is no processing to be done.”56

Synesthesia is just one of a multitude of experiences that one can experiment with in lucid dreams; we’ll be discussing many more possibilities in chapter 4. I suspect that every experience that’s possible with a psychedelic plant or drug is also possible within a lucid dream. But before we start discussing all of the incredible things that one can do in a lucid dream, let’s first take a look at the fascinating scientific research into the phenomenon.