IMPROVING LUCID DREAMING AND DEVELOPING SUPERPOWERS IN THE DREAM REALM

Dream on, dream on, dream on. Dream until your dream comes true.

AEROSMITH

Evidence supports the notion that anyone can learn how to dream with lucidity, given enough time and effort. Some people appear to be born with a natural gift for conscious dreaming and report having had spontaneous lucid dreams since early childhood, such as Will Culpepper, who sent me the following account:

I had my first lucid dream when I was about eight years old. In the dream I was in the factory that made the children’s magazine Disney Adventures, observing the huge stacks of paper and giant printing machines. All of a sudden, a man made of fire appeared behind me and started chasing me. As I ran through the factory, he shot flames out and ignited the stacks of paper all around. Suddenly, something struck my attention. Despite the fact that I was running for my life, I had the presence of mind to notice something funny about a clock on the wall. I stopped to look at it and realized that it went up to 13 instead of 12. My first thought was, That’s not right. I must be in a dream. Taking a leap of faith and trust, I then told myself, Well, if I’m dreaming, then when I open this closet right here there will be a fire extinguisher. Sure enough, when I opened the closet door I found it completely empty except for a single fire extinguisher. I grabbed it, turned around, and extinguished the guy made of fire, and that’s the last I remember.

I interviewed a twelve-year-old boy from Bali named Jazz Mordant, who has been having vivid lucid dreams since the age of three or four. He told me that he often consciously intervenes in frightening dream scenarios so as to achieve better outcomes in the dream. He described dreams in which he was surrounded by scary monsters, where he learned how to control their minds in order to protect himself:

During my experiences with mind control during my lucid dreams I have been able to completely manipulate and alter the way different beings react and decide things in the dream world. The way that I do this is very simple, although it took me ages to figure out. All you have to do is give it all of your intention and think about the way you want them to act, and see it happening—and your imagination will become reality. However, I cannot control some people and beings in my dreams, as when I try to they realize this and look at me as if I’m crazy.

I’m not one of these dream prodigies like Jazz. I didn’t start having lucid dreams until I was a teenager.*15 However, I’ve always had vivid dreams, and I had a lot of frightening nightmares as a young child. Then I began having lucid dreams when I was sixteen, not long after I started experimenting with meditation, cannabis, and LSD. Thanks to the use of these mind-expanding substances and my own mental discipline, over the course of my life I’ve had hundreds of prolonged lucid dreams, some of which appear to have lasted for hours, and I’ve had a few magical periods where I seemingly never lost lucid consciousness during a whole night of sleep.

My interest in lucid dreams, and my skill at inducing and sustaining them, was largely cultivated in my early twenties through my interactions with Stephen LaBerge, whom I interviewed in 1993 for my book Mavericks of the Mind.*16 In LaBerge’s 1985 book Lucid Dreaming, I learned that one’s proficiency at lucid dreaming can be improved, and that lucid dreaming is a learnable skill that improves with practicing specific techniques and setting strong intentions.

Around 50 percent of the population has experienced a lucid dream at least once in their lives, and around 20 percent of the population has around one lucid dream a month. However, only around 1 or 2 percent of the population experiences lucid dreams more than once a week.1

When dream researchers Robert van De Castle and Joe Dane surveyed people to distinguish potentially successful lucid dreamers from nonlucid dreamers, they found that “subjects with a spirit of adventure, who wished to explore the unknown and had a rich curiosity about the ranges of human experiences, were excellent candidates for lucidity.”2 Most lucid-dream researchers believe that the ability to have lucid dreams is present in everyone, and evidence supports the notion that anyone can get better at having lucid dreams with practice. However, frequent lucid dreaming requires continued practice and strong intent, or the frequency of one’s lucid dreams will start to diminish. In other words, increasing lucid-dream frequency is more like training for an athletic sport than it is like learning how to ride a bicycle.

But wait, before we get started . . .

CAN LUCID DREAMING BE DANGEROUS?

I initially thought that this was a silly question, as one can’t possibly get physically harmed in a lucid dream, and there are so many potential benefits and delights. However, after reading an essay about using lucid dreaming in psychotherapy, by Gestalt therapist Brigitte Holzinger, I began to understand why it might not be a good idea for some people to experiment with lucid-dream induction techniques. Holzinger provides a case study of one psychotic person who ended up committing suicide as a result, it seems, of his repeated experiences dialoguing with “the devil” in his lucid dreams.3

Negative reactions to lucid dreaming appear to be quite rare, but, as with using psychedelics, it may not be a wise idea for someone who has difficulty distinguishing reality from fantasy to start experimenting with a technique that will make one’s experience of life bigger, weirder, and more mysterious than it already is. As Ryan Hurd writes, “If we grant that lucid dreaming may be powerful enough to heal, then we must also admit that it may also be powerful enough to do us harm. Otherwise, lucid dreaming is not really the medicine so many claim it could be.”4

Hurd’s warning sounds like it might apply equally well to both lucid dreaming and psychedelic journeys. However, psychophysical researchers Celia Green and Charles McCreery theorize that lucid-dreaming practices might actually be helpful for some people suffering from schizophrenia: “In the case of a schizophrenic person feeling out of control of various aspects of his or her mental life, it is possible that the experience of gaining control over at least one of them, namely distressing dreams, might have a generalized therapeutic effect, quite apart from the localized relief that might be obtained for the particular symptom.”5

Nevertheless, a disturbing example of a negative outcome involving lucid dreaming can be found in the case of a twenty-two-year-old schizophrenic, Jared Lee Loughner, who shot a U.S. congresswoman and eighteen other people in Tucson, Arizona, in 2011. Initially judged incompetent to stand trial due to paranoid schizophrenia, in August 2012 Loughner was judged competent to stand trial, and at the hearing he pleaded guilty to nineteen counts. In November 2012 he was sentenced to life plus 140 years in federal prison. Loughner was very interested in lucid dreaming, and also had a history of using psychedelic drugs, which may have worsened his condition. Just days before the shooting he posted a series of videos on YouTube that included his observations about dreaming, one of which included the frightening statement, “I am a sleepwalker—who turns off the alarm clock.” Some commentators wondered whether Loughner thought that he might have been dreaming at the time of the shooting.6

When my colleague Ryan Hurd was reviewing the account of Loughner in this book, he told me, “The salient point is that lucid dreaming is probably a more common symptom of schizophrenia than typically recognized, and that comes with sleep degradation and arousal disorders in the early stages of the condition. Sleep paralysis is another symptom of early-stage schizophrenia.” Eerily, Loughner sent an innocent-seeming e-mail message to Hurd eighteen months prior to the shootings, asking his advice about lucid dreaming. An article on the Gawker website that includes Hurd’s correspondence with Loughner also includes a series of fascinating excerpts from Loughner’s dream diaries.7

Other people have raised concerns about lucid dreaming interfering with the quality of one’s sleep, causing a loss of interest in one’s waking life, or creating the risk of “bad trips.” Although not conclusive, all of the initial studies with lucid dreamers have found these fears to be unfounded,8 although people have had some frightening experiences during lucid dreams on occasion. In fact, Ryan Hurd confirmed that “new research shows clearly that ‘bad trips’ are not uncommon but probably underreported.”9

Others have raised concerns that by lucid dreaming we interfere with the natural symbolic communication process between the unconscious and conscious parts of our mind. Yet this doesn’t seem to be a concern to frequent lucid dreamers for two reasons: First, no one can ever gain complete control over what happens in a lucid dream; there’s always an element of surprise, and even the best lucid dreamers, it seems, can only achieve lucidity on occasion. And second, one could argue just the opposite—that we can more effectively understand the unconscious meaning of dreams by examining them consciously while they are actually occurring. It’s hard to see how being less aware and insightful about what’s happening to us can be helpful.

In his book Astral Projection, Oliver Fox includes a list of the supposed occult dangers of lucid dreaming, such as “heart failure,” “insanity,” “premature burial,” “temporary derangement caused by the noncoincidence of the etheric body with the physical body,” “cerebral hemorrhage,” “obsession,” and “death.” However, after listing these supposed dangers he states, “I would not dissuade any earnest investigator with a passion for truth. He will be protected, I believe by the unseen intelligences that guide our blundering efforts in the divine quest, and the merely frivolous inquirer will soon be frightened away by the strange initial experiences.”10

I suspect that there’s truth behind Fox’s encouraging words, and that for most people lucid dreaming is a safe and healthy way to explore new possibilities. So what’s the best way to get started? Studies have repeatedly demonstrated that there is a strong correlation between overall dream recall and lucid-dreaming frequency.11

ENHANCING DREAM RECALL

Scientific evidence suggests that we never actually lose consciousness when we go to sleep. This may sound surprising, but in studies where people were woken up during every different stage of sleep and asked what was going on in their minds, they usually had an answer of some sort. We’re thinking, feeling, or dreaming the entire night, it seems, but the brain mechanism responsible for encoding our experiences into long-term memory is switched off when we go to sleep.

The explanation for this may lie in the original biological function of dreaming, which is so that we can strengthen useful memories and discard useless ones. If this is true, then it would make sense that during this process our memory systems would be unable to store new data. As we learned, REM sleep patterns are not a reliable indicator that people are dreaming, because people not only report dreams during NREM sleep, studies have confirmed that people can have lucid dreams during the NREM stages of sleep.12 However, as many know, oftentimes remembering your dreams can be maddeningly difficult. On many mornings all I can remember from my dreams is that I was somewhere, with someone, doing something that I was very involved with. As Australian dream scholar Robert Moss writes, “The typical dreamer, after waking, has no more idea where he spent the night than an amnesiac drunk.”13

So how can we learn how to remember our dreams? Primarily, by having the intention to do so prior to going to sleep, and by habitually recording one’s nighttime experiences. It’s important to make a commitment to turn on the light (or use a flashlight or an audio recorder) and write down (or record) every dream you remember when you first awaken and it is fresh in your mind. Even though our long-term memory storage system is largely turned off while we sleep, our short-term memory system still works. I’ve found that one partial sentence is enough to start the flow from the land of lost dreams. Just start writing. Before you know it, more and more details come back to you as you’re writing the dream down or recording it.

If you don’t consolidate the memory of the dream by remembering and reflecting on it in your waking state immediately upon awakening, then most likely it will be lost in the astral void—although oddly, sometimes some random stimulus during the day will trigger a dream memory from the previous night. If this happens to you, record it in your dream journal. I also find that lingering elements from dreams that vanish upon awakening may return a few moments later if I’m drifting back to sleep, and so it’s important to get up and record these fragile memories at the time, before falling back asleep, if you don’t want to lose them. There may also be a unique, state-dependent memory system operating within the dream itself that we can’t access in our waking state, as I and others have reported experiencing memories of previous dreams while lucid dreaming.

Many successful lucid dreamers will confirm that the best way to begin one’s personal experimentation with lucid dreaming is by simply learning to pay more attention to one’s dreams. The best way to do this is by keeping a written record of one’s experiences and experiments in the dream realm.

Keeping a Dream Journal

- The first step in enhancing dream recall is to obtain a suitable journal or notebook. Scientific research has demonstrated that being motivated and keeping a dream diary can substantially improve dream recall.14 The more beautifully designed the journal or notebook, the more ornately decorated and magical looking, the better, I think, as this whole project is about the alchemical blending of one’s imagination with reality.

- Next, one needs to get into the habit of writing down what one has experienced while sleeping immediately upon awakening. It is important to keep your journal and a flashlight right next to your bed, or, as I mentioned earlier, you can use an audio recorder if you prefer. I used a written journal for years. Now I use the speech-to-text app on my iPhone, then transfer the report to my computer and edit the text in the morning.

- Get into the regular habit of recording what happened while you were asleep. If you don’t remember any dreams, then write “no dream recall,” but include how you feel. When you recall a dream, write down any fragment, scene, emotion, memory, or feeling that you can remember. Write down every detail. Draw pictures or illustrate the report, if this feels appropriate. I think that it also helps to give each dream a title, like a poem or a short story, based on a central theme, as they are stories, first and foremost.

- One often finds that the process of writing down a few dream fragments or feelings brings back other memories from the dream, sometimes surprisingly a flood of them. The more you do this, the more you naturally enhance your dream recall, and this is the first step toward having a lucid dream.

- It’s important to keep a written record, so that you can more easily examine and compare the dreams. This means that if you use an audio recorder to capture your dreams in the middle of the night, it’s important to transfer these experiences into your journal for easier reference later on.

The late occult writer Oliver Fox remarks on the importance of keeping a journal of one’s lucid dreams and nighttime experiences:

What is it that our spiritual experiences, like the roseate hues of early dawn, are so fleeting, so difficult to retain in our mind? Swiftly the exaltation passes; the memory becomes blurred; we question its reality. Did that really happen? I have gone further than many people along a certain path. I have talked with Masters in another world. I have seen—though from afar—Celestial Beings, great shapes of dazzling flame, whose beauty filled the soul with anguished longing. And yet were it not for my records, the blessed written words— which ensure permanence, even though they veil and distort and make untrue—were it not for these, there are times when I should doubt everything; yes, even the reality of my Master. So hard is it to kill the skeptic in me, nor do I want to altogether; for skepticism is very useful as an aid to preserving mental equilibrium.15

Does consciously observing, recording, and reflecting on our dreams change them? Russian occultist P. D. Ouspensky thought so:

Dreams proved to be too light, too thin, too plastic. They did not stand observation, observation changed them. What happened was this: very soon after I had begun to write down my dreams in the morning and during the night, had tried to reconstruct them, thought about them, analyzed and compared them with one another, I noticed that my dreams began to change. They did not remain as they were before, and I very soon realized that I was observing not the dreams I used to have in a natural state, but new dreams were created by the very fact of observation.16

That observation effects measurement is a well-known conundrum from quantum physics. It appears that the very act of observation changes what we’re looking at, causing a wave of possibilities to collapse into a single event. In chapter 10 we’ll be discussing the philosophical implications of this perplexing insight, but in the meantime let’s get to know what it’s like to wake up in our dreams.

HOW TO HAVE A LUCID DREAM

As I mentioned in the introduction, there are levels of lucidity within the dream state, from what has been described as “prelucidity” to “superlucidity.” In the early stages of lucidity development, one simply suspects that one might be dreaming during the dream, while in the more developed stages one can become just as aware during the dreaming state as one is during the waking state. Then, sometimes, people can even become more aware in their lucid dreams than they are during ordinary waking consciousness, and have life-transforming mystical experiences as a result.

During a low-awareness lucid dream, one may only be in partial control of one’s cognitive skills, and sometimes in this state one can make erroneous judgments that seem to be obvious errors upon awakening, and one may also initially have poor impulse control. In many of the early lucid dreams that I had, I immediately rushed off to fulfill impulsive desires, and it took a fair amount of lucid-dream experience before I was able to progress beyond mere attempts to satisfy my most basic, unfulfilled desires, as I often found myself simply doing these things without really thinking. With practice, though, I was able to tame these wild impulses, which became part of the deeper, personal psychological healing that I described in chapter 1. I subsequently advanced into deeper levels of possibility with lucid dreaming.

I asked Stephen LaBerge what kind of techniques he thought were the most effective for producing lucid dreams. Before responding to this question he said, “If you were to say, ‘I want to become a lucid dreamer, how should I go about it?’ I would say that means you’ve got some extra time and energy in your life, some unallocated attention that you could apply to working on this. If you’re somebody who is so busy that you have hardly the time to take a walk, you’re not going to have the time and energy to do this.”

This is an important point. Learning how to lucid dream takes time and effort. One needs to have the time for practicing the techniques, as well as a commitment to developing and improving one’s skill over time. With persistence and dedication it appears that anyone can master these techniques. However, just taking an interest in them may be enough to start having lucid dreams. Researchers Celia Green and Charles McCreery say, “For those who wish to start developing lucid dreams, a simple prescription, which may be sufficient, is to think about the idea of lucid dreaming before falling asleep each night. Some people keep a book about lucid dreaming by their bedside and read part of it each night to focus their mind on the idea.”17

With forty-three books about sleep, dreaming, and lucid dreaming piled next to my bedside as I write these words, I can’t help but laugh when I read the above quote. In any case, be sure to keep this book by your bedside, and every time you see its beautiful cover art by Cameron Gray remember to question whether or not you’re dreaming.

Aside from reading books about lucid dreaming before going to sleep, there are basically two ways to achieve lucidity in a dream state. The first is by maintaining a certain degree of self-awareness as one is falling asleep, staying conscious or mentally alert to a degree through the entire process of falling sleep and entering the dream state. This can be quite an amazing experience, and I find that I can only do it when I’m in a certain state of consciousness to begin with as I’m falling asleep. (Some of the herbal, nutritional, and pharmacological methods that I and others have used to help reach this state of awareness are discussed in the next chapter.)

Maintaining an alert and watchful state of consciousness as one is falling asleep can also sometimes be a bit frightening, as it involves passing through stages of sleep paralysis. I’ve heard people describe the experience differently, but for me it goes something like this: The process of allowing my body to fully and completely relax can produce euphoric feelings and hypnagogic imagery behind my closed eyes. As the experience deepens, and I start to fall asleep, I pass through a stage where I am still aware of my body and my surrounding bedroom, but anxiety-raising auditory hallucinations become superimposed on it. Then, as my body is humming from the euphoria of deep relaxation, I’ll start to hear people talking outside my house, or I’ll hear someone coming up the stairs to my bedroom. These auditory hallucinations seem completely real, and I always have to convince myself not to be afraid, that they are just dream imagery (or spirits), and there is nothing to be concerned about. This takes a lot of willpower; I’ve woken myself up out of the process many times, just to make sure that there really was no one in my bedroom. However, if I stay with it and surrender to the experience while maintaining lucidity, I start to see more intense hypnagogic imagery, sometimes fractal and psychedelic patterns, combined with an opiatelike bliss. Soon the shifting imagery solidifies into the environment of a lucid dream.

Dream lucidity achieved in this manner has been termed WILD by Stephen LaBerge—wake-initiated lucid dreams. One of the methods that LaBerge suggests for achieving this is by counting while falling asleep, repeating the phrase “I’m dreaming.” So as one is drifting off into dreamland, one occupies one’s mind with the ordinal phrases, “One, I’m dreaming. Two, I’m dreaming. Three, I’m dreaming . . . ” Practicing this technique may help you to paradoxically stay awake while falling asleep, but even if you can’t maintain mental alertness through the process of falling asleep, often this technique will cause you to awaken in your dream later, or so I have found and others have reported.

Maintaining a vigilant state of observing your awareness through hypnagogia (the transitional state from wakefulness to sleep) all the way into sleeping and dreaming states of consciousness can be an extraordinarily magical and blissful experience. Every night, it seems, we pass into these mentally playful, image-associating states that are truly psychedelic and absolutely delightful to experience. When I’m in them they seem instantly familiar, and it appears that I pass through these states whenever I go to sleep, but I almost always forget them. It takes a sustained effort of focused awareness to do this, and a commitment to waking up to record what happens, but the results are well worth the effort, I assure you.

This method is in contrast to the other way to achieve lucidity in a dream, which LaBerge calls DILD, or dream-initiated lucid dreams. DILD involve “waking up,” so to speak, within a dream, and realizing that you are dreaming while it is already happening. This awakening to a greater sense of awareness is usually due to having an enhanced critical perspective, so that one notices something bizarre or strangely out of synch between what is happening in the dream and what one knows to be possible in waking reality. LaBerge calls these strange inconsistencies with physical reality “dreamsigns,” and he says that if we remember them, they can help us recognize when we are dreaming.

One way to increase our chances of experiencing a DILD is by actively looking for common dreamsigns in the records of our dream journals. Again, this is why it’s so important to have a written record, as it’s generally easier to recognize common dreamsigns when one is examining them visually, in writing.

Another DILD technique, also developed by LaBerge, called the mnemonic induction of lucid dreams, or MILD, is based on memory training that is meant to be applied just after one has awakened from a dream and can easily fall back asleep. Upon awakening from the dream, this technique involves rehearsing the dream in your mind, imagining yourself becoming lucid in it as you are falling asleep, while repeating this statement: “The next time I’m dreaming, I will remember to notice that I’m dreaming.”

Studies have shown the MILD technique to be the most effective DILD method for the induction of lucid dreams.18 To learn more about MILD, WILD, and DILD, see LaBerge’s book Exploring the World of Lucid Dreaming. Meanwhile, let’s make sure that we’re not dreaming right now . . .

TESTING YOUR REALITY

One of the techniques that has worked well for me is something that I also first heard about from Stephen LaBerge. It’s a technique that one learns to practice throughout the day, originally developed by the late psychologist Paul Tholey, called the critical reflection technique. To practice this method, one gets into the habit of continuously asking oneself the question, Am I dreaming right now?

The idea behind doing this regularly when we’re awake is that we’ll carry the habit into our dreams, where we will discover that we are dreaming. Lucid-dream expert Daniel Love calculated that we spend around 11 percent of every twenty-four hours in bed dreaming, which means that if people get into the habit of asking themselves regularly if they’re dreaming right now or not, then they will have a better than one in ten chance of being correct!19 However, to answer this question it’s important that you actually test your environment to determine conclusively whether or not you are dreaming. If you don’t get into the habit of actually testing your environment to see if you really are dreaming or not, then when you ask yourself in a dream if you’re dreaming you’ll be likely to just do the same thing—not carefully examine your reality, and then just conclude that you’re not dreaming.

You must ask the question sincerely each time for this to work properly. Try it right now. Put down the book, look around, and genuinely ask yourself, Am I dreaming right now? Now, when you answer this question, be prepared to explain how you know for sure that you’re correct. Remember, it’s not always so obvious. The dream world can look as convincingly real as waking reality. Testing the world around you to see whether or not you’re dreaming involves doing at least one of several things.

Pinch your nose: One of the easiest ways to test what reality you’re in is to try breathing through your nose while pinching your nostrils closed. There’s a glitch in the dream matrix here, as one can easily breathe through one’s nostrils when doing this in a dream. By the way, the expression of disbelief, “I pinched myself to see if I was dreaming,” would actually be a rather poor reality test in a lucid dream because one’s dream state is quite capable of producing a dream sensation of a pinch that is convincing enough to fool the dreamer.

Read written words, look away, look back and read them again: Another easy test is to simply look at something written on paper, look away, and then look back and see if the same words are still there. Expect to discover that you’re dreaming while you do this. In a dream environment, the words will almost always change when you look away and then look back again. This is the method that I use the most, as it always works for me, and for most people—but not everyone, as there are some cases where writing stays consistent in dreams. My girlfriend told me about a dream that she had where she repeatedly looked at the writing in a book, looked away, and looked back, only to discover each time that the writing was always the same, and she never achieved lucidity in that dream. It was almost as though the dream was mocking her attempts to become lucid. However, in general, although a dream environment can appear every bit as realistic as waking reality, the stability of the world is usually substantially decreased, and its fluidity, mutability, and vulnerability to our personal psychic influence is substantially increased. When I stare at written words in a lucid dream they never remain stable for more than a few seconds and always start to morph.

Pull on your fingers to see if they elongate: Robert Waggoner suggests this as an additional way to test which reality one is in. In a dream, your fingers will stretch out like Silly Putty.

Turn the light switch on or off: When you’re in a dream, the light switch usually doesn’t do anything when you move it, as is famously portrayed in the film Waking Life.

Try passing your hand through a solid physical object: First, imagine that you can do so, and then try it. In a dream it’s possible to move your body through physical objects, but sometimes this takes a bit of practice. An easy way that people can do this is by simply trying to poke one’s finger through the palm of the opposite hand.

Try to recall the events that led up to the situation you currently find yourself in: When I try to recall the events that led up to the situation that I find myself in, I always discover that these memories are simply not in my mind when I’m dreaming. Some people suggest using this reality test as a lucidity-trigger technique by asking oneself the question How did I get here? Regularly asking yourself how you got into the situation that you currently find yourself in can carry over into your dreams, where you may realize that you can’t remember how you got to where you are in the dream, and consequently you become lucid.

Try using your imagination: Some other lucid dreamers and I—as well as some characters in my dreams that I’ve questioned—also can’t seem to use our imaginations within a dream, i.e., we can’t visualize things in our minds while we’re in the dream state, perhaps because the world that we’re in during a dream is in our imagination. However, some people report being able to do this, and these people find that whatever they visualize in their dream significantly affects the dream environment.

Reality-test reminders: Some people write messages on their hands to remind them to test their reality when they look at their hands during the day, or they use an app on their phone that sends random text messages to remind them to ask that important question Am I dreaming right now? One of my favorite reality-test reminders is a beautifully crafted talisman, designed by dream researchers Ryan Hurd and Lee Adams, that has ancient alchemical imagery etched into it. It’s a magical, coinlike object that I carry around with me, and every time I find it in my pocket I look at it. On one side is a snake-adorned, eight-pointed sun with a celestial face, and on the other is a crescent moon within an eye, held between branching, intertwining tree limbs. “Are you awake?” it asks on the sunny side, and “Are you dreaming?” it asks when you flip it over. This talisman turns up in my pocket during both my waking life and in dreaming situations.

Fig. 4.1. The Lucid Talisman, designed by Ryan Hurd and Lee Adams, is available at https://dreamstudies.com/shop/exclusives/lucid-dreaming-talisman (photo by the author).

Try to fly: Here’s a fun reality test, although it’s not something that one can easily do in just any situation. Still, it helps me—try to fly! I do this in my living room in waking reality and it carries over into my dreams. See if you can elevate yourself longer than gravity usually allows by simply jumping into the air and thinking, I’m going to fly! If you appear to linger in the air for even a tiny fraction longer than usual, then the situation deserves further investigation, so it’s important to try it again.

Some people have been known to go through fairly complex procedures and considerable lengths to determine whether or not they are dreaming. Consider the following 1938 report from German psychologist Harold von Moers-Messmer, one of a handful of researchers who investigated lucid dreaming in the first half of the twentieth century:

From the top of a rather low and unfamiliar hill, I look out across a wide plain towards the horizon. It crosses my mind that I have no idea what time of year it is. I check the sun’s position. It appears almost straight above me with its usual brightness. This is surprising, as it occurs to me that it is now autumn, and the sun was much lower only a short time ago. I think it over: The sun is now perpendicular to the equator, so here it has to appear at an angle of approximately 45 degrees. So if my shadow does not correspond to my own height, I must be dreaming. I examine it: It is about 30 centimeters long. It takes considerable effort for me to believe this almost blindingly bright landscape and all of its features to be only an illusion.20

However, many advanced lucid dreamers report that they simply know when they are dreaming, without having to test their reality, as one’s state of consciousness is most definitely different in a dream state than in a waking state. With practice we can learn to recognize the state of consciousness that we’re in while dreaming as a dream sign, to alert us to the fact that we’re dreaming, thereby allowing us to achieve lucidity. The state of consciousness that one is in while in a lucid dream is a lot like the state of consciousness that one is in while tripping on psychedelic drugs or visionary plants. Have you ever witnessed people tripping on acid for their first time? They often find the wispy vapor trails that follow their hand movements to be tremendously fascinating.

LOOKING AT YOUR HANDS IN A DREAM

In Carlos Castaneda’s book Journey to Ixtlan, the Mexican shaman-trickster Don Juan says to Carlos,

Tonight in your dreams, you must look at your hands. . . . Every time you look at anything in your dreams it changes shape. The trick in learning to set up dreaming is obviously not just to look at things, but to sustain the sight of them. Dreaming is real when one has succeeded in bringing everything into focus. Then there is no difference between what you do when you sleep and what you do when you are not sleeping.21

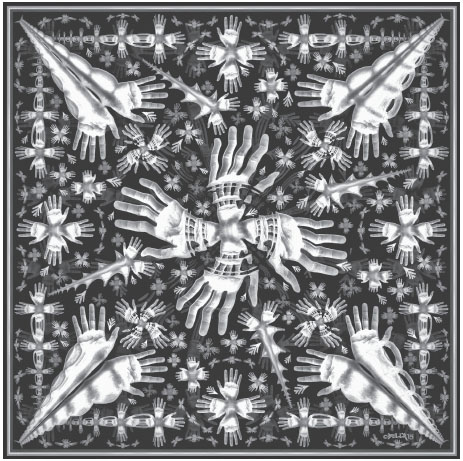

Fig. 4.2. Reach for Your Dreams, by Frank Alan Bella (www.bellastudios.com)

When Castaneda saw his hands that night in a dream he became lucid and realized that he was dreaming. I read this account when I was sixteen, not long after I had taken LSD and had my first lucid dream, and it had a profound effect on me because I knew what he was talking about. Many people have had lucid dreams after reading Castaneda’s account, and others have had success using a variation on this technique that is described by Robert Waggoner as “finding your hands” in a dream to become lucid. It goes like this: stare at your hands before going to sleep while telling yourself that when you see your hands in the next dream, you’ll realize that you’re dreaming.22

In the 2007 film The Good Night, the character played by Martin Freeman repeatedly becomes lucid in his dreams each night when he looks at his hands. In addition to being a lucidity trigger, there’s something powerful about simply looking at your hands while in a lucid dream. For example, in a Lucidity Institute experiment, the participants were instructed to study their hands while in a lucid-dream state, and the reports from these experiments included bizarre variations of the hands, like having extra fingers.23

A contributor to a website forum, “James1982,” writes about the technique of looking at your hands in a lucid dream: “The idea is that, in your dreams, your hands will never look normal. This has been my experience. Sometimes my hands will look almost like I am viewing them through a kaleidoscope, other times I will have extra fingers, or my fingers will all be of a vastly different length and thickness. A few days back I had a lucid dream where my hand became fractal, and each finger had a hand on the tip, which in turn had a hand on each finger, so on and so forth.”24

Actually, in lucid dreams, my hands generally appear pretty normal-looking, but I have noticed that newborn infants look at their hands a lot. I’ve also noticed that people who first try virtual reality or LSD often spend time initially just watching their hands and fingers move. It seems that one of the first things we all do upon entering a new state of consciousness or a new level of reality is examine our hand-eye connection. There are more neural connections between the hands and the eyes than between any other two parts of the body. It was a revelation for me when I realized that there’s nothing that I see more of in life than the backside of my own hands.

More than a few people have mentioned to me that they became lucid after seeing the backside of their hand in a dream, so try to let your hands be a constant reminder of dream lucidity. Also, looking at one’s dream hands can sometimes help to sustain unstable lucid dreams. As I mentioned earlier, you may want to try writing the words Am Idreaming? (or a symbol that carries this meaning) on the palm of your hand, and then remember to test your reality every time you see it, as this will likely carry over into the dream state.

Fig. 4.3. Infinite Lucidity, by Bump Goose (www.itszen30.com)

SETTING STRONG INTENTIONS AND USING AUTO-SUGGESTION

Reminding yourself of your intention to lucid dream before you go to sleep at night can be helpful, according to some reports, and I found this to be true in my own personal experience. Doing this in a relaxed, meditative, hypnotic, or trancelike state may be especially helpful. Say to yourself, Tonight I will be awake in my dreams. Repeatedly visualizing or imagining oneself being awake in a dream scenario appears to help increase the likelihood of it happening. This method is an extension of a process known as dream incubation, which means going to sleep with the explicit intention of having a particular kind of dream. As I mentioned in the introduction, dream incubation began in ancient Greece and Egypt, where temples devoted to different deities were used by people who would go there to sleep at night in order to receive divine knowledge in their dreams, often about how to treat a particular illness.

Dream incubation works well when synergistically combined with other methods, especially those that disrupt normal sleep patterns.

Imagine that your throat is glowing: An ancient lucid-dreaming induction technique from Tibetan Buddhism is to imagine that a red lotus flower with four leaves is glowing at the base of one’s throat as one is falling asleep. The Tibetan symbol Ah is supposed to be visualized, glowing in white, in the center of the lotus flower during this process. Alternatively, one can imagine a candle flame, a red pearl, or a simple white light, radiating upward from the bottom of your throat as you enter into the hypnogogic phase of sleep. This helps to sustain an aspect of your awareness into sleep, and it can also influence dream imagery, which may trigger lucidity. For example, people may see their necks glowing or radiating light after they fall asleep, which could help them recognize that they’re dreaming.

is supposed to be visualized, glowing in white, in the center of the lotus flower during this process. Alternatively, one can imagine a candle flame, a red pearl, or a simple white light, radiating upward from the bottom of your throat as you enter into the hypnogogic phase of sleep. This helps to sustain an aspect of your awareness into sleep, and it can also influence dream imagery, which may trigger lucidity. For example, people may see their necks glowing or radiating light after they fall asleep, which could help them recognize that they’re dreaming.

The wake-up-back-to-bed method: Another technique that a lot of people have had success with in inducing lucid dreaming involves setting an alarm clock to go off in the early morning hours, during the latter part of the sleep cycle, when there’s more time spent in the REM stage of sleep. This “wake-up-back-to-bed” (WBTB) method was developed by Stephen LaBerge and his colleagues. By waking up a few hours earlier than you normally would and then doing something to arouse your brain, like walking around, reading, or going to the bathroom, and then going back to sleep around a half hour to two hours later, you can sometimes induce lucid dreaming.25 This technique becomes even more effective when combined with some of the other methods described in this book, such as the MILD technique, along with one of the dream-enhancing herbal or nutritional supplements, or drugs, described in the next chapter.

Mild sexual stimulation: Here is a lucid-dream activation technique that has worked well for me, which I haven’t heard about anywhere else (but I doubt that I am the first to figure this one out). It involves very gently massaging my own genitals, keeping myself in a very mild state of sexual arousal as I fall asleep. This technique has helped me for years in achieving WILDs, when combined with the MILD technique. Another, similar technique that hasn’t worked as well for me, but others say has been effective, involves holding one’s arm in a raised position as one is falling asleep. This will usually wake one up repeatedly as he or she is dozing off, and the idea is that it helps to train your mind to maintain a steady state of awareness and a memory of physical reality as one is falling asleep.

Meditation: Having some form of regular meditation practice may also be helpful in inducing lucid dreaming. Various studies have demonstrated that people who meditate lucid dream more frequently than people who don’t, and the longer the amount of time that people have practiced meditation, the more frequently they lucid dream.26 Like lucid dreaming, some forms of meditation appear to be another example of a hybrid or paradoxical biological state of arousal. Some people seem to enter a state in which cortical arousal (or higher-level brain activity) is accompanied by extreme physical relaxation.27 Additionally, it has been found that people are more likely to experience lucid dreams in the days following meditation practice compared to days when they don’t practice.28 This paradoxical state of arousal appears to occur when people have out-of-body experiences (OBEs) as well. Preliminary studies suggest that as a group, people with a tendency to have OBEs are more easily able to enter into a state in which cortical arousal is associated with muscular relaxation.29

Meditation is essential for developing awareness in dreams in the practice of Tibetan dream yoga (which I will be discussing in chapter 10). Personally, I started practicing Transcendental Meditation (TM) when I was fourteen. TM involves the silent repetition of a mantra in one’s mind; not insignificantly, I had my first lucid dream when I was sixteen, shortly after I first tried LSD. Silently repeating a mantra as one is falling asleep can also be helpful in maintaining an aspect of waking consciousness through the process of falling asleep and into dreaming. I sometimes just repeat a simple phrase like I’m awake as I’m falling asleep, to keep the waking centers in my brain engaged; sometimes the continuous repetition of the words can be helpful in escorting me into a DILD. When done correctly, the body falls asleep while the mind remains awake.

In addition, as part of my lucid-dream practice, I’ve been developing my skill at insight meditation, or Vipassana, another Buddhist practice that cultivates mindfulness. This simply involves carefully observing the contents of one’s mind without attachment—just observing, paying close attention to what one is thinking and how one is thinking. Vipassana allows you to attain a state of consciousness that transcends the mantra-repeating TM meditation practice that I had been doing since I was a young teenager. I started doing this mindfulness practice in a traditional meditative pose, sitting with my eyes closed, but now I find that I’m able to hold that state of mindfulness for a few seconds at a time as I do whatever I’m doing during the day. During the meditation, I basically just let my breath rise and fall on its own, allowing my thoughts to rise and fall on their own—like watching trees blowing in the wind—while simply bearing witness. The level of metacognition achieved by doing this allows one to escape memories of the past, anticipations of the future, and the ceaseless chattering of the “monkey mind.” As a result, one’s illusory sense of having a personal self dissolves into the present moment, allowing you to realize your true nature as the ever-present field of consciousness silently observing it all.

Sleep deprivation: Curiously, I have found that not getting enough sleep can sometimes trigger lucid dreaming, and going a whole night without sleep will sometimes trigger lucid dreams if I nap during the morning hours. Many people also report increased lucid dreaming when they sleep extra hours or experience disrupted sleep, and it’s known that people who suffer from narcolepsy—a disorder that causes people to suddenly fall asleep—have 28.3 percent more lucid dreams.30

Staring at a digital clock: Spending time every day looking fixedly at a digital clock can sometimes carry over into one’s dreams, where looking at it for longer than a few seconds can serve as a lucidity trigger, because the numbers won’t stay fixed in a dream.

Sleep sitting up: Another method incorporated into Tibetan dream yoga practice to increase the frequency of lucid dreams is to go to sleep sitting up. I’ve found that going to sleep or napping with my back relatively straight, using pillows and armrests to keep my head elevated, does increase my lucid dreams. Anthropologist Charles Laughlin went to great lengths to carry out experiments that followed a Tibetan dream yoga technique, by building himself a foam-lined box made out of plywood approximately four feet higher than his shoulders when he was sitting in a half-lotus position, so that he could sleep sitting up without falling over. Laughlin reports, “Thus began a rather crazy time in my life due to the most intense dreamwork I have ever undertaken. I slept sitting up for months, and though I was never able to remain conscious throughout the night, I spent much of my sleep in lucid dreaming, wafting in and out of the waking and dream states and recording experiences on paper as I could.”31

If sleeping sitting up sounds too uncomfortable, then perhaps try sleeping on your right side (which is also part of Tibetan dream yoga) or on your back. According to a study conducted by physician Lynne Levitan, people are three times more likely to have a lucid dream while sleeping on the right side of their body or on their back, compared to sleeping on their left side.32 During the course of writing this book I noticed that all of my lucid dreams occurred when I was either sleeping sitting up, on my back, or on my right side. This could be due to the possibility of certain body positions activating different sites in the brain.

Sleep somewhere new: Sleeping in unfamiliar surroundings also appears to increase the frequency of lucid dreams. A recent study, which helps to explain this, demonstrates that whenever we sleep in a new location, one of our brain hemispheres tends to stay more alert than usual while we’re sleeping, similiar to the way marine mammals sleep. This may help to explain why lucid dreaming occurs more often in these situations.33

Sleep alone: Sleeping alone can significantly increase my ability to lucid dream because I’m generally so easily aroused when I sleep with my partner. I’ve found the lucid-dream state to be quite fragile, and movements by my partner can easily wake me up from a lucid dream. Going to sleep in a separate location, such as on the couch or in a sleeping bag on the floor, during the early morning hours can be a good way to avoid these unnecessary awakenings when one is experimenting with lucid-dreaming techniques. Additionally, as we learned above, sleeping in a new location can also serve as a lucidity trigger.

Sleep with the lights on: I have discovered that another effective technique for inducing lucid dreams involves leaving an overhead light on in the room where you are sleeping. This technique can be even more effective when combined with sleep deprivation. Obviously, overhead illumination makes it difficult for most people to fall asleep, but if you can fall asleep with the lights on then it may help to keep a part of your brain awake while you’re sleeping. Of course, getting a good night’s sleep every night is important for maintaining healthy body and brain function, so sleep deprivation and overhead illumination aren’t really methods that you should use regularly.

Timing: An important factor in learning how to lucid dream more frequently is timing. There are many shifting variables and factors that need to come into just the right alignment in order to lucid dream. Some of these include your own psychological preparation and expectations, where you are in the sleep cycle, your neurochemistry, and, unquestionably, various mystery factors, as it seems that nothing guarantees a lucid dream every time. Still, timing is critical. Since we spend more time in REM sleep during the end of the sleep cycle, this is when it’s best to try to increase the probability of having a lucid dream.

As you can see, there are quite a few different methods that people have developed for waking up in one’s dreams over the past few thousand years, and especially so in recent years. This chapter just scratches the surface. There are some excellent books that cover methods in greater depth than I do in this chapter. Two of the best summaries can be found in LaBerge and Rheingold’s book Exploring the World of Lucid Dreaming and Daniel Love’s book Are You Dreaming?

MIXING, BLENDING, AND SYNERGIZING TECHNIQUES

Part of the trick to having regular lucid dreams is to combine different techniques and practice them regularly. Studies by Stephen LaBerge and others have demonstrated that combining WBTB and MILD techniques can be synergistic, and this is one of the most effective ways to train people how to lucid dream.34 European dream researchers Tadas Stumbrys and Daniel Erlacher have found that the most effective lucid-dream induction procedures include the following steps:

- Set your alarm clock to go off six hours after you go to sleep.

- Go to sleep.

- Wake up and remember a dream.

- Stay awake for one hour practicing MILD.

- Go back to sleep.

According to Stumbrys and Erlacher’s research, if you follow these instructions, there is a 50 percent chance that you will achieve lucidity in your next dream.35

HOW TO SUSTAIN A LUCID DREAM

Once you start learning how to become lucid in your dreams, the most common problem you will likely encounter is that you’ll get so excited in the dream that you are physically aroused into full wakefulness. Getting too emotionally excited in a lucid dream can cause one to fully wake up, so it’s best to learn some form of self-control, which meditation can help with. This is one of the first lessons to learn in lucid dreaming: control of one’s emotions is essential if one wishes to sustain the dream state. Self-control is not only necessary to sustaining a lucid dream, it is also necessary to controlling (or guiding) aspects of the dream. As husband-wife dream researchers Jay Vogelsong and Janice Brooks point out,

Dream control is, at bottom, self-control, since dreams come from our minds. If controlling “them” or “it” does not always work, as LaBerge maintains, it is precisely because we often falsely conceptualize dream imagery as external to ourselves. Not only can we not control our dream selves without affecting dream imagery too, we cannot control the imagery without affecting ourselves, since such control requires monitoring our own thoughts and perceptions. It makes little difference, then, whether the dreamer wrestles [with] the fear to master the monster or wrestles [with] the monster to master the fear, since both come down to essentially the same thing: the one is a projection of the other.36

Another way to help sustain a lucid dream if you feel it starting to fade is to move your visual field around, looking at the tapestry of the world around you without focusing too much on the details. As I mentioned earlier, looking at your dream hands can help you stabilize an unstable lucid dream, as can trying to calm your breath, mind, and dream body. Doing “dream yoga”—posturing your dream body in a lotus position or some other yogic posture, closing your dream eyes, and meditating, all within a lucid dream—can not only help you stabilize the dream, but can promote seeing “closed-eye,” trippy tryptaminelike visual patterns that other oneironauts and I have seen.

A method that I learned from Stephen LaBerge to help sustain lucid dreams works quite well. This involves having your arms in the dream fully outstretched to either side at right angles to your body, closing your dream eyes, and then spinning around in circles, like a whirling dervish. The efficacy of this technique is likely due to the involvement of the vestibular system*17 in the production of the rapid-eye-movement bursts in REM sleep.37 According to Stephen LaBerge, “An intriguing possibility is that the spinning technique, by stimulating the system of the brain that integrates vestibular activity detected in the middle ear, facilitates the activity of the nearby components of the REM-sleep system.”38 In any case, not only does this technique help to sustain and stabilize a lucid dream, it gives one the option for greater control. While you’re spinning around, try visualizing the environment that you’d like to be in, or who you’d like to be with; oftentimes when you open your eyes you’ll find that your vision has been realized.

I can generally sense when a lucid-dream state is getting close to ending. In one experience that I didn’t want to end, I did my utmost to stay there:

I could sense that the lucid dream was coming to an end soon, so I raced around asking everyone in the dream if they knew how I could stay there. No one knew. Then I came upon a wise-looking African woman wearing a long, colorful dress. Her stomach was bulging and she was clearly pregnant. When I asked her how I could stay, she just looked at me, smiled, and pointed to her stomach, implying that the only way to stay there is to be born there. Then I awoke.

I had another lucid dream with this same African woman several months later:

The wise African woman (from my previous lucid dream) and I were in the back seat of a car together. As the lucid dream was dissolving, I once again turned to her and asked her how I could stay there. Then she just smiled and replied cryptically, “I’ll see you when you get home.”

I’ve pondered the philosophical significance of the wise African dream character’s responses quite a bit, and I’ll be discussing my thoughts on this more in chapter 9, but the point that I’m making here is that I love being aware in my dreams so much that I usually don’t ever want them to end.

I’ve only twice experienced lucid dreams that I wanted to end. The first time was because I knew that my physical body was in trouble. I fell asleep after taking a dose of the nutritional supplement GBL (which I’ll be discussing in chapter 5) with my head accidently under the covers, which obstructed my breathing. I had this powerful and disturbing lucid dream:

I had this black cloth mask over my face and a jacket on that was making me hot and uncomfortable. It was very difficult for me to breath. I kept taking the cloth mask off my face, over and over, but every time I took it off it would instantly reappear on my face within seconds. I would drop it on the floor, and then it would instantly disappear and reappear on my face. I would pull it off my face, and then instantly it would reappear, no matter how many times I took it off. And I took it off dozens and dozens of times. I would show this to the people I was with—friendly guys and a girl—and they were equally mystified by my inability to remove the black cloth from my mouth. Then I became lucid in the dream and I realized what was happening. I knew that I had fallen asleep with my head under the blanket, that I couldn’t breathe, and that this was the cause of the weird experience in the dream. So I tried to wake myself up from the dream, again and again, but I couldn’t. I told the other people in the dream what was goingon—that I had fallen asleep with my head under the covers, and they understood, but they couldn’t help me. It was very weird and disturbing. I finally did wake up, and oh, what a relief it was to take my head out from under the covers!

During that frightening experience my body was so strongly sedated from the GBL that it had to sleep, but my mind was awake and aware of the breathing problem that could have suffocated me if I didn’t wake up in time. This, however, was the result of a freak accident.

The only other time that I wanted to wake myself up from a lucid dream, I did so very quickly, simply by willing myself to wake up. I did so, and I was sorry afterward that I had. This was the only time that I ever became frightened in a lucid dream due to what I was experiencing in the dream realm:

After achieving lucidity, I asked the dream to show me what it thought I needed to see. Then, rather abruptly and dramatically, the dream environment immediately began to change, shift, and get liquid or fluid, similar to melting wax. Suddenly, I found myself by a swimming pool. Then, within seconds, this unattractive, masculine-looking woman came right up to me and looked into my face. She was really scary-looking for some reason, didn’t say a word, and although I didn’t recognize her, she looked strangely familiar. She had short black hair, was very “butch,” and was similar in appearance to the androgynous “woman” who raped my mouth in a previous lucid dream, only more frightening-looking. I wasn’t sure what she was going to do—and it was definitely the most frightening figure I’ve ever encountered in a lucid dream. She seemed very disapproving, critical, and judgmental of me, and I got instantly scared—for reasons that I can’t seem to fully understand. So I deliberately woke myself out of this dream.

I’ve pondered this experience a lot, and I wondered if I was being shown that a part of my mind was critical of the frivolous way that my ego had been pursuing primal pleasures in my lucid dreams. I was disappointed in myself for becoming too scared to face that woman in my dreams, and for waking myself up before I heard what she had to say. I told myself that if the opportunity ever arose again, then next time I’d see what that intimidating dream figure had to say.

Several weeks after this dream occurred, I had a partially lucid dream in which this disturbing woman appeared again—and this time I heard what she had to say. It was upsetting, I didn’t want to hear it, and I lost my lucidity when I did. After becoming lucid again I impulsively began searching for sexual pleasure, and as I became more aroused . . .

I suddenly found myself talking with a dark-haired woman who told me that she had been raped when she was younger. I became very disturbed by what she was saying and I again lost my lucid awareness. She told me that not only did she enjoy being raped but that it had been “a gift from God.” This shocked me. I told her that being raped isn’t a gift from God, and I tried to move away from her, but she followed me and was persistent in telling me this. I went outside the house that we were in to get away from her, and I was now in my childhood neighborhood. I went inside a car parked on the street, closed the door, and I began to scream at the top of my lungs. I was concerned that someone might hear me, and then I awoke.

Upon awakening, I realized that the dark-haired woman in the dream was the same woman who appeared in my previous lucid dream, when I asked my dreaming mind what it thought I needed to see. I’ve interpreted this as a message from my unconscious about the conflicting mix of disturbing feelings that resulted from my early sexual trauma, and about the fact that I can’t easily tease apart these early traumas from my fruitful interest in shamanic healing and psychedelic medicine.

In any case, this previously described episode was the only lucid-dream experience, out of hundreds that I’ve had, where I ever became genuinely frightened by the content and sought to end the experience—no doubt precisely because it lay at the crux of my healing. Since it was easy for me to exit the disturbing dream, and since I generally never want my lucid dreams to end, and because most people are trying to sustain lucid dreams for as long as possible, it came as a surprise when someone who is well versed in shamanic states of consciousness seriously asked me how you can physically awaken from a lucid dream if you want to and was having trouble doing so. She told me that she had found herself in horrific lucid dreams that she couldn’t control and wanted to learn how to wake up from them if she needed to.

The Ojibway people of the Lake Superior region in North America are famous for creating dreamcatchers, ornately designed circular nets that have feathers and strings of beads hanging down from them, which are hung above the bed.39 The idea behind these seemingly magical objects is to prevent nightmares, so that the dreams that come to a person while sleeping must first pass through the filtering net of the dreamcatcher, where bad dreams get trapped in the spiderweblike, crisscrossing netting of the dreamcatcher, while good dreams drip down onto our heads through the hanging beads and feathers. Many New Age bookstores carry dreamcatchers, and I have a beautiful one hanging over the head of my bed. I tend to have a lot of good dreams, so you may want to try this too. However, if having a magically crafted dreamcatcher fails to prevent nighttime episodes of terror from jarring your mind, then research done in this area leads me to believe that it’s probably healthier psychologically to confront the disturbing or dark dream forces head-on and deal with them in the lucid dream, rather then trying to escape from the situation by waking up.

Although not all researchers agree, some psychotherapists think that transforming one’s negative dream images into something more positive will symbolically transform negative personality traits into positive ones, or that doing this can solve genuine psychological problems. According to Stephen LaBerge, one doesn’t even need to interpret the symbolic meaning of a dream to achieve psychological integration through reconciliation or by using methods to alter the dream. LaBerge says that while the dream conflicts that he resolved may have depicted actual personality conflicts, he “was able to resolve them without even having to know what they represented,” through his “acceptance or transformation of whatever unidentified emotion, behavior, or role they stood for.”40 My own personal experience leads me to believe this too. This was why the lucid dream I mentioned in chapter 1, in which I transformed my rapist, was so powerfully healing. In fact, some psychotherapists teach their clients methods for lucid-dream induction as an effective treatment for chronic nightmares.41

HOW TO END LUCID NIGHTMARES

If you find yourself becoming lucid in a nightmare, LaBerge and others recommend confronting the evil person, monster, demon, or dark force directly. Sometimes simply asking what the uninvited predator or beast wants, or offering a gesture of love or warmth to it, can make the creature simply dissolve or can transform it into something friendly. In that healing dream that I presented in chapter 1, I described how I transformed the person raping me in the dream into a caged bird, by swiping my hand repeatedly over the person’s face.

Dream characters often seem to be fragmented parts of ourselves, and by making friends with the scary characters—what Jung would collectively call “the shadow”—in our dreams, many psychologists and lucid-dream enthusiasts believe that we integrate disconnected parts of ourselves back into the whole of our personality.

When I interviewed Jazz Mordant, the twelve-year-old boy from Bali whom I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, he told me about how he ended his lucid nightmares:

When I was smaller I used to have nightmares, and there was one creature with a green face and strange powers that always came back. I was very scared of it, so much so that I wouldn’t want to go to sleep at night. After a while my mom told me something that helped. She said to look at it straight in the eye and say, “Go away and never come back”—and I had to put all of my will, intention, and energy into making it disappear. So I did. I looked at it and said, “Go away and never come back,” until the point where I was yelling. Then I saw it slowly move further away until it vanished entirely.

Asking other characters in the dream for assistance is another idea that has been reported to sometimes work, but I think that the best approach of all is just reminding yourself that your body is perfectly safe in bed, and that nothing in a dream can ever really harm you—that is, except for the emotion of fear. The terror that people experience in nightmares can have physical ramifications, such as increased heart rate and other physiological symptoms, sometimes severe enough to actually cause injury or even death, according to some researchers.42 *18

Though physical harm resulting from a nightmare is rare, realizing that one is safe within a dream can be tricky. For some people, relief in this manner may be elusive, as dream scholar Ryan Hurd points out:

I believe there is . . . potential for the slow digestion of lucid nightmares over a lifetime, in particular when we are forced to sit with existential truths and forces that cannot be resolved simply by the brave act of facing them, talking to them calmly, or absorbing their otherness into our egoic dreambodies. Sometimes more is required than courage and the ability to transform dream imagery; sometimes the willingness to be transformed is essential. Conversely the assumption that moving toward reconciliation in lucid nightmares— as opposed to killing and fighting—is always for the best also has a humanistic and ethnocentric bias that has been in favor ever since the Senoi theory*19 was discredited. Sometimes we still need to fight.43

Psychologist Patricia Garfield recommends fighting and killing aggressive dream characters as well, but only so that you can convert their negative energies into positive energies and make allies of their essences or spirits.44 (Garfield also encourages lucid dreamers to indulge in sexual activities within their dreams as often as possible, as a way to help integrate the fragmented parts of one’s psyche.) Some people, of course, express the opposite opinion, such as psychologist Robert Van de Castle, who writes, “To murder a dream character would be to commit a form of intrapsychic suicide,”45 †20 Van de Castle feels this way about murdering dream characters because, if we adopt the viewpoint that the various figures that we encounter in a lucid dream can be conceptualized as components of the dreamer’s personality, then it would be unwise to kill or harm some threatening figure in a lucid dream because this figure would be a part of one’s self.

I found Hurd’s and Garfield’s perspectives noteworthy. Although they’re addressing a situation that I’ve never had to deal with personally, I’m reminded of a friend’s experience. After a friend and I journeyed together on ayahuasca several years ago, she wrote me excitedly several days later to say that she had experienced her first lucid dream. I was eager to hear what had happened. Flying and sex are two of the experiences that most people gravitate toward initially, and I was expecting to hear something along these lines. However, I was nonplussed to learn that my friend used her first experience with lucidity to physically attack the other characters in her dream, an act she described as doing with great zeal and pleasure. I was a bit shocked to hear this, but it appears that this may have been a healthy response to the violent nightmares that have plagued her since childhood, when she was traumatized. She maintains that the experience was therapeutic, cartoony, and even fun, and she encouraged me to try it, but I never felt inclined to. In one lucid dream I threw a rock at a dream character when he wouldn’t respond to me, and then felt sorry for doing so when he looked at me.

When I asked Ryan Hurd what he would recommend to someone having a lucid nightmare, he said:

In general, I suggest that people ground themselves, remind themselves that they’re safe, face their fear as much as possible, and ask for help—whether that might be a dream ally, an ancestral connection, God, the divine, or whatever is appropriate for them. Just take it as it is, and if it doesn’t resolve or you wake up, don’t feel too bad about it—because if it’s a nice repetitive nightmare you don’t have to worry, it’ll be back.

In any case, it can’t hurt to have a method for ending a lucid dream in one’s bag of tricks. Let’s say that Nightmare on Elm Street’s Freddy Krueger, or some other vengeful spirit that supposedly attacks people in their dreams, isn’t responding to your dream hugs, and you would really rather wake up.*21 Or maybe you just want to wake yourself up so that you can record details from your lucid dream that you don’t want to forget.

Oftentimes, emotional arousal and willpower are all that’s needed to physically activate the body into wakefulness. Many lucid dreamers report that they can wake themselves up from a dream by simply willing it, any time that they want to. It’s hard to verbalize exactly how this is accomplished—like trying to explain how you move your body—but I can usually do it. Some people just have the natural ability to wake themselves up from a lucid dream, and many lucid dreamers deliberately wake themselves up so that they can write down ideas or experiences before they’re forgotten. If you don’t naturally have this ability, then here’s what you might try: Just as moving your eyes or spinning around can help to sustain and stabilize a lucid dream, sitting still and focusing your attention on a fixed point in the environment can help you to physically awaken. Another technique is to try holding your breath, which you can maintain voluntary control over while you dream, and sometimes this sudden loss of respiration can shock the body into waking up.

A friend told me that as a child whenever she had lucid dreams and wanted to wake up she would jump into a body of water, and this always seemed to do the trick. (On the other hand, I’ve had some absolutely delightful lucid dreams where I swim around in pools of water. The kinesthetic sensation of swimming and floating is realistic, although the sensation of feeling “wet” doesn’t feel quite as it does for me in the waking world. In a lucid dream the water feels real when I’m submerged in it, but my skin feels instantly dry when it emerges. Other people have also reported the same difficulty reproducing the physical sensation of wetness in a lucid dream.)

So if you do manage to wake yourself up out of a lucid dream, then you have to ask the following question . . .

AM I REALLY AWAKE?

The tricky thing to remember about waking up from a lucid dream is that you need to confirm that you really are awake and aren’t experiencing a “false awakening.” This occurs when you think you have woken up but are in fact still dreaming—that is, dreaming that you are in bed, having woken up. There can sometimes be layer after layer of these kinds of false awakenings, called “nesting dreams,” until you finally arrive back in the true reality of your waking physical body.

I’ve experienced a similar phenomenon while coming out of a ketamine-induced shamanic journey, where I would repeatedly think that the experience was over and that I was back in my body and bedroom, only to discover that I was actually in some weird parallel-universe version of my bedroom. Sometimes these “false endings” of the shamanic journey would happen multiple times until I was finally back in my bedroom where I had begun the journey. I’ve heard others describe similar experiences with Salvia divinorum (such as ethnobotanist Daniel Siebert, who describes this experience in chapter 9).

TESTING OUT YOUR DREAM-REALM SUPERPOWERS

Rather than trying to awaken from nightmares, the vast majority of people who achieve lucidity in their dreams couldn’t be more ecstatic. It’s hard to describe just how amazing it feels the first time you achieve lucidity in a dream to someone who has never experienced it. Like a psychedelic experience, lucidity in a dream can dramatically increase the sensory magnitude of whatever it is that one is experiencing, and people often describe seeing the world around them in magnificent detail. For example, in 1902, at the age of sixteen, occultist Oliver Fox reported the following experience:

I was dreaming! With the realization of this fact, the quality of the dream changed in a manner very difficult to convey to someone who has not had this experience. Instantly, the vividness of life increased a hundred-fold. Never had the sea and sky and trees shone with such glamorous beauty; even the commonplace houses seemed alive and mystically beautiful. Never had I felt so absolutely well, so clear-brained, so inexpressibly free! The sensation was exquisite beyond words; but it only lasted a few minutes and then I awoke.46

In a dream, you have the power to do almost anything imaginable, as every physical law can be bent, twisted, and broken, and you have far more control over the experience of reality than we do in the physical world. It takes a while to actually realize this, because initially we tend to assume that the dream world operates with the same forces and constraints as the waking world.

In his book Are You Dreaming? author Daniel Love accurately describes what it feels like to arrive in the realm of lucid dreaming: “Here, we find ourselves in a world where, like some kind of deity, we have an ‘all you can eat’ buffet laid out before us, containing all possible human (and beyond human) experiences ready for our personal enjoyment.”47

What were previously ways to test to see if you’re dreaming or not now become abilities with which to enjoy and explore the dream state. Pretty much whatever you believe is possible in a lucid dream becomes possible, although there appear to be neurological or psychological limits as to how much of a dream you can control. I’ve learned how to do many of the things that I love doing in lucid dreams by reading the accounts of other lucid dreamers. Every time I read about something that I never thought of, I add it to my list of things to try out in future lucid dreams. However, there are some people, such as Robert Moss, author of Conscious Dreaming, who suggest that after becoming lucid it’s a good idea to let the dream unfold as it naturally would have, only with your conscious awareness carefully observing and paying close attention.

As Robert Waggoner points out in his book Lucid Dreaming: Gateway to the Inner Self, people can only influence their lucid dreams, not control everything that happens in them. There’s still a mysterious agency (the unconscious?) that appears to be crafting everything behinds the scenes. In other words, there’s no way to avoid surprises. This notion will be explored in depth when we get to chapter 10. Meanwhile, here are some of the things that your dream self is capable of doing, which you may want to try out the next time you find yourself lucid in a dream:

Fly: The first thing that many people want to do in lucid dreams is achieve lift off and fly. I suspect that this desire to feel the joy of flight comes from our current evolutionary condition as larval forms of what we will one day become—like caterpillars dreaming of becoming butterflies. Flying is easier for some than it is for others in lucid dreams. Some take to it without much effort, and others find that it takes considerable practice to do well.

I’m always thrilled when I take a test leap and feel myself linger in the air longer than gravity would allow, but I find that it takes a certain form of concentrated effort to elevate myself, to stay in the air, and to fly. However, once I get going—wow!—the soaring sensation is amazing, and the extraordinary views can be absolutely spectacular. Next time you’re in a lucid dream, try jumping into the air and holding out your arms. Movement of some type may be necessary at first to convince your mind that it’s possible. Try flapping your arms or swimming through the air, for example. My girlfriend says that she likes jumping from rooftop to rooftop in her lucid dreams. In the dream realm, gravity only exists if you believe it does. Also, having real-life experience in hang-gliding or skydiving can help to create the memories that build worlds from within a lucid dream.