CONSCIOUS DREAMING AS A PATH TO SPIRITUAL AWAKENING

O you who fear the difficulties of the road to annihilation—do not fear. It is so easy, this road, that it can be traveled sleeping.

SUFI APHORISM

You are dreaming . . . from then on I was watchful, even in dreams, to separate the real from the unreal.

YOGANANDA

Morpheus is the Greek god of dreams; his name means “shaper of dreams.” The related word morph is often used to describe the shifting, transformative nature of a psychedelic vision or its digital representation, while morphine is the name of that powerful, dream-inducing opiate drug. Notably, Morpheus is also the name of the captain of the flying ship Nebuchadnezzar*50 in the classic science-fiction film The Matrix, which presents the idea that everything we think of as reality is really a computer-generated simulation—much like lucid dreaming.

Neo, the hero of The Matrix, gains his strength through realizing that reality is created by his mind, a concept that resonates with much of Eastern philosophy. For example, the word buddha means “awakened one.” To be awake, in the Buddhist sense, means to wake up from the dream or illusion of being a separate self, so in some sense all lucid dreamers are buddhas, at least temporarily, when they realize that the world around them is a dream is composed of their own mind.

The parallels between becoming lucid in a dream and having a mystical experience in waking reality are truly striking and thought-provoking. In both cases, you become acutely aware that the person you think you are is just a temporary illusion, and in both cases you remember that you have another existence that you have forgotten about. In both cases, having this experience of “awakening” generally brings an immediate sense of joy, a profound loss of fear, the lifting of an amnesia that you didn’t even realize was present, and the delightful realization that so much more is possible than you had previously thought. Celia Green expresses this well when she explains how frequent lucid dreamers sometimes come to view all of life as a kind of dream:

The idea that the whole of life might be in some sense a dream, which seems more characteristically to occur to habitual lucid dreamers, consists in admitting a qualitative distinction between waking life and ordinary dreams, but going on to consider that there may be an equally qualitative distinction between waking consciousness and some “higher” form of consciousness. The relationship between this supposed higher state of consciousness and normal consciousness would be analogous to the relationship between normal waking consciousness and non-lucid dreaming.1

Throughout this book we’ve considered the possibility that dreams might be more real and meaningful than many people commonly believe. Now, paradoxically, we are asked to consider the possibility that both dreams and what we experience as the waking world may be illusions, and be equally unreal.

Stephen LaBerge expresses well how we can recognize the illusory nature of dreams, and he describes how we can learn to see what we think of as the “real” world as actually being the inside our own mind in a dream:

Lucid dreamers realize that they themselves contain, and thus transcend, the entire dream world and all of its contents, because they know that their imaginations have created the dream. So the transition to lucidity turns dreamers’ worlds upside down. Rather than seeing themselves as a mere part of the whole, they see themselves as the container rather than the contents. Thus they freely pass through dream prison walls that only seemed impenetrable, and venture forth into the larger world of the mind.2

Consider Celia Green’s further assessment:

It seems possible that the failure to make the necessary distinction between a lucid dream and a non-lucid dream arises in part from a psychological resistance in recognizing the uncertain philosophical status of the “external world” of waking life. In order to preserve our belief in the unquestioned status of the physical world, and our secure grasp of “reality,” it is perhaps desirable that dreams should be regarded as something as distinctly unreal as possible. If it becomes clear that they can rival the waking world in perceptual precision and clarity, and that the state of a person’s mental functioning in a dream can seem to be not much different from that of waking life, we may start to ask ourselves uncomfortable questions about how good a claim to superior reality our waking life actually has.3

With the attainment of lucidity in a dream comes the memory that one has another life as a human being on earth. Does this experience have parallels in the mystical experiences of the waking world? Yes, it does, and when this happens people often say that they remember having a spiritual existence that transcends their biological life, sometimes along with what are referred to as past-life memories. Some people also say that these memories can influence our dreams.

MEMORIES OF PAST LIVES

There are many people who claim to have memories of living lifetimes as other people, and some significant scientific research has been conducted to verify these claims. The work of psychiatrists Ian Stevenson, Brian L. Weiss, Stanislav Grof, and others provides many compelling examples of cases where it appears that, at the very least, personal information or traumas have mysteriously traveled from the death of one person and into the birth of another.

Stevenson worked at the University of Virginia School of Medicine for over fifty years, was its department head for ten years, and is the author of three hundred scientific papers and fourteen books about reincarnation. He collected hundreds of cases that he believes provide evidence of past-life memories, and instances where birthmarks correspond with the wound on a deceased person that a child was said to recall. If you’re interested in reading Stevenson’s work, a good place to start is his book Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation.

Brian Weiss is a Yale University–trained clinical psychologist who had been treating a patient who began discussing what appeared to be past-life experiences while in hypnosis, and although Weiss was skeptical at first, he later became convinced that these memories were real, after confirming elements of his patient’s story through public records. After becoming convinced of the validity of his patient’s experience, Weiss began using a technique called past-life regression in his therapy. He offers some compelling evidence for his convictions in the book Many Lives, Many Masters. Weiss believes that a lot of common phobias, recurring nightmares, anxiety attacks, and even physical ailments are rooted in past-life experiences, and that people can learn to overcome these ailments by understanding their cause in a previous lifetime.

A number of psychotherapists besides Weiss have incorporated the doctrine of reincarnation into their practice. These practitioners generally refer to themselves as past-life therapists and have formed an organization called the Association of Past-Life Therapy and Research.

Psychiatric researcher Stanislav Grof, who conducted more LSD studies than any other scientist on the planet, has described how there were numerous examples in the therapeutic psychedelic sessions that he ran where he encountered convincing evidence for past-life memories among his subjects, such as unexplainable knowledge of obscure historical facts or archaic languages.4

The late “psychic sensitive” Edgar Cayce advocated the study of dreams and promoted the idea that dreams may reflect past-life experiences. Cayce’s work has had a big influence on many people. According to its website, the organization that he founded, the Association for Research and Enlightenment (A.R.E.), boasts “centers in 37 countries, and individual members in more than 70 countries,”5 with around 25,000 members.6

Additionally, and most significantly, the concept of reincarnation— that one’s essential awareness transcends death and progresses through numerous incarnations—is basic to the religions and philosophies of most Asian, Australian Aborigine, tribal African, and Pacific Island cultures, and is also found in many Native American tribes. Clearly, the concept of reincarnation has great appeal to many people.

However, even if confirmed as true, past-life memories may not be personal; they could be experiences that arise due to interacting with information that is stored in the collective unconscious, and their possible existence doesn’t necessarily imply that the person experiencing the memories has lived before as that separate unit of consciousness. However, confirmation of these kinds of memories certainly stretches the limits of what we currently know to be true, and Weiss’s accounts of people healing through past-life regression therapy are most compelling.

When I spoke with psychologist Ralph Metzner about this subject, he told me:

I have for many years now included past-life regression methods in my psychotherapy practice, if the search for causal factors of present problems in childhood or in prenatal experience, as well as from parental influences, has been unproductive. Past-life regression therapy uses a light hypnotic trance state, in which the practitioner guides the client to ask questions of their inner/higher self— questions about past-life connections to their current-life issues. Such approaches can be very revealing and bring about profoundly healing changes in attitudes. Successful past-life regression therapy does not require commitment to any particular belief system or theory of reincarnation. An openness to the possibility is the only prerequisite and, as in any healing practice, it is the results that count. Many people, myself included, have reported flashes of insights and seeming memories of other lives during group or shared psychedelic experiences.

I have a friend who told me that she often has dreams in which she is other people, of different ages, ethnicities, and both sexes; something I’ve rarely experienced myself. In one particularly arresting dream of hers (mentioned in chapter 7), she said that she died repeatedly in the dream and then immediately woke up right after dying each time, in the same bed, in the same bedroom—but as a different person. My friend said that this happened many times in her dream, and that she could see her reflection as different people in her bedroom mirror when she seemingly awoke after each “death” in the dream. When she told me about this I couldn’t help but wonder if this dream was based on memories she had of previous incarnations, or possibly on a memory of the reincarnation process.

Could commonly recurring nightmares or emotionally charged dream themes that seem to have no relationship to one’s current life be caused by the residue from events that occurred in a previous lifetime or lifetimes? This is a question that no one can really answer, but the question becomes especially interesting when we compare it to how we think about our current life when we achieve lucidity in a dream. In a lucid dream we know for certain that we have at least one other life—as the person lying in bed who is having the dream—and that other existence in the waking world unquestionably has a huge influence on what one experiences in the dream realm.

According to past-life researchers, memories from a previous life can come to people while they are either awake or when they are dreaming. Stanley Krippner explains: “When this information comes from dreams, the dreamers visually experience themselves participating in a scene during some earlier time before their present lives. At other times, the dreamers simply observe the scene in a dream. In either case, the dreamers claim that they cannot account for these images by events in their present life situation.”7

When I interviewed Robert Waggoner I asked him about the possibility of using lucid dreaming as a tool to explore past-life memories. He responded with some words of caution:

I did a paper . . . on seeking past-life experiences while lucidly aware, because I realized as I went deeper into lucid dreaming that seemed a possibility. Normally, I don’t talk about this and share it too much with lucid dreamers because there are some difficult aspects of seeking out past-life information in lucid dreams. I’ll give you an example: For a period of about nine months, that’s what I did in lucid dreams—I sought out past-life information. And it began to seem that I had awakened within my larger awareness, past-life . . . I’ll just call them “selves” or “awarenesses.” So one day I was at my local grocery store doing the daily shopping. I was pushing my cart along, and I could feel one of these newly awakened awarenesses within my stream of consciousness. And as “we” turned the corner and came to the meat counter, I could hear it say clearly in my head, Oh my— they keep cut up dead pieces of animals where they store their food. So imagine a meat counter in your normal grocery store. You have sixty or eighty feet of steaks and pork chops and chickens, all basically dead animals chopped up. Of course, the Robert-me had never considered that. But this larger awareness, or different awareness, that I’d kind of woken up by virtue of seeking out past-life selves in the lucid-dream state was utterly horrified by this. And so the caution that I’m trying to bring out is that a lucid dreamer . . . has to keep clear in your head what your thoughts are and your stream of consciousness, and not get confused by other streams of consciousness that you might have awakened. So that’s one of the interesting things that a person can do. But I do think that the flexible or the malleable nature of space and time that we oftentimes see in our dreams and lucid dreams means that in dreaming, and also lucid dreaming, we oftentimes have experiences that connect with past lives. And also sometimes the dream symbols that seem so odd and unusual to us, I assume . . . must have connections with either past-life memories or other incarnations that we’re just not aware of in this ego-life.

Notably, both the practice of lucid dreaming and a belief system based upon the concept of reincarnation are part of the structure of Tibetan Buddhism.

TIBETAN BUDDHISM AND LUCID DREAMING

Lucid-dreaming methods have been used for thousands of years in different shamanic and religious traditions, and perhaps no tradition has a more developed and integrated system of lucid-dream training than Tibetan Buddhism.

Tibetan Buddhism is a branch of Buddhist philosophy that resulted from the cultural integration of the Mahayana branch of Buddhism developed in India, which incorporated many of the tantric techniques of Hindu traditions and the shamanic Bön tradition of Tibet, which already had a long history of developing sophisticated techniques for training people how to dream with lucidity.*51 Lucid dreaming is also a part of Hindu traditions, where the practice is referred to as “dream witnessing.”

As mentioned earlier, the word buddha is Sanskrit for “awakened one.” It’s important to reemphasize the significance of this term in our discussion here, as the term “awakening” is given to both the experience of arising from sleep and to gaining a sense of greater spiritual awareness.

The philosophy of Buddhism began around 2,500 years ago, in the foothills of the Himalayas, with the spiritual awakening of Siddhartha Gautama, a wealthy Sakyan prince who left his palatial life of luxury to see the world and reach enlightenment—that is, to awaken to a deeper understanding of reality. As the story goes, Siddhartha’s birth was heralded by a prophetic dream. Siddhartha’s mother, Queen Maya, reportedly dreamed that a white elephant with six tusks ran into the palace, loudly trumpeting. It circled her bed three times and then dove into her womb, through the right side of her ribcage. Upon awakening, Maya interpreted the dream as an omen that her child would bring a special gift to the world.

As a young man, Siddhartha left his lavish palace of cushioned luxury, whereupon he then shockingly encountered all of the suffering and misery in the world that he had been carefully sheltered from in the palatial bubble of his gated kingdom. Undeniably changed by what he had witnessed, Siddhartha became a sannyasi, an ascetic who renounces the ordinary world. He practiced meditation with other ascetics and nearly killed himself attempting to reach his goal of spiritual liberation as a result of methods that involved starvation and other forms of extreme asceticism. Dissatisfied with his spiritual progress using the traditional methods, Siddhartha eventually committed himself to stubbornly sitting under a Bodhi tree until he finally “woke up,” or awakened to his true nature.

Supposedly Siddhartha just sat there meditating for forty-nine days straight under the Bodhi tree, fighting against an army of ferocious demons until he finally came to realize the illusory nature of the physical universe—as well as the “self ”—within the larger reality of consciousness. From this experience, Siddhartha built his philosophy and created a spiritual practice that teaches people how to reach the state of consciousness that he attained under the Bodhi tree, by recognizing desire and attachment as the cause of all suffering, and by being kind and learning how to tame one’s mind.

Well before Buddhist philosophy merged with the indigenous Tibetan Bön tradition, it appears that Siddhartha himself encouraged lucid dreaming. According to Buddhist scholar and lucid-dreaming teacher Charlie Morley, “In the Pali Vinaya, the original rulebook for monks and nuns, the Buddha actually instructs his followers to fall asleep in a state of mindfulness as a way to prevent ‘seeing a bad dream’ or ‘waking unhappily.’”8 Later, when Buddhism traveled to Tibet and merged with the more shamanic Bön tradition, the resulting system not surprisingly placed a lot of emphasis on teaching practices that promote conscious dreaming, and for thousands of years the Tibetans have refined and mastered their techniques.

Dreaming plays an important role in Tibetan Buddhism for many reasons. Dreams are used to help predict future events, to receive spiritual teachings, and to find the location of reincarnated masters. However, it is the practice of dream yoga, which incorporates advanced techniques that include lucid dreaming as a method of helping people to recognize the illusory nature of everything, including oneself, that is unique to Tibetan Buddhism. In his book Openness Mind, Tarthang Tulku, a Tibetan lama, writes about how “advanced yogis are able to do just about anything in their dreams. They can become dragons or mythological birds, become larger or smaller or disappear, go back into childhood and relive experiences, or even fly through space.”9

Despite how attractive these awesome superpowers might seem to the average person, they are discouraged for wish-fulfillment purposes by dream yogis, who regard the pursuit of these pleasures as trivial distractions that prevent one from reaching higher spiritual realizations.*52

According to Tibetan Buddhist philosophy, dreams and death are closely linked. Dreams are seen as an important example of illusion and impermanence, as well as a training ground for teaching us how our minds create temporary, ever-shifting models of reality. Our nightly dreams are understood within this perspective to be dreams within a larger dream, secondary illusions within the primary illusion of waking life, where death is seen as a portal, a passageway for transporting one’s soul from one lifetime to another through a region of the universal mind known as the bardo, the intermediate place between realms.

Using the terms region, place, and realm in the previous sentence could be misleading, as the bardo is not actually a location, but rather a transitional state of consciousness; it translates literally as “intermediate state.” Dreams are considered to be similar to the postmortem bardo, and descriptions of the bardo are often reminiscent of the state of being experienced on a psychedelic journey. In fact, the very first guidebook written by Westerners for planning and navigating a healthy psychedelic journey, The Psychedelic Experience, by Timothy Leary and colleagues, was modeled on the Bardo Thödol, or Tibetan Book of the Dead, an ancient manual on how to meditate while dying and how to recognize opportunities for spiritual liberation and navigate the postdeath bardo to consciously reincarnate.

According to Johns Hopkins psychologist Katherine MacLean, “A high-dose psychedelic experience is death practice. You’re losing everything you know to be real, letting go of your ego and your body, and that process can feel like dying.”10

In Tibetan Buddhism, dreaming and the bardo state are recognized as being so similar that dreaming is used as a path to spiritual liberation, in the practice known as dream yoga. This practice is considered essential to recognizing illusory states for what they really are and to developing valuable abilities for use at the moment of death and thereafter. The basic idea behind Tibetan dream yoga is that if someone can learn how to extend meditative awareness throughout sleep and dreams, then he or she can apply this ability to dying and death when the time arrives. Just as a dream is seen as a bardo between falling asleep and waking up, so the postdeath bardo describes an intermediate state between death and rebirth, which is said to be dreamlike in nature. The primary goal of dream yoga is to extend the transcendent state of lucid awareness developed during lucid-dreaming practices while alive into the postdeath bardo while dying and immediately afterward.

Dream yoga can be used as a powerful tool for spiritual growth, although it seems that simply lucid dreaming can also benefit one spiritually. When people regularly experience lucid dreams, over time it appears that they will naturally begin to progress through predictable developmental stages.

STAGES OF PSYCHOLOGICAL AND SPIRITUAL DEVELOPMENT WITH LUCID DREAMING

In Robert Waggoner’s book Lucid Dreaming: Gateway to the Inner Self, the author describes five developmental stages that he has observed in himself and in others as they lucid dream.11 Waggoner’s insightful descriptions of these different stages ring true for me, and for others. Briefly, these unfolding mental stages involve a process of discovery and a phase where one needs to overcome temptations, fears, and defenses. This is followed by a period in which one learns how to transcend one’s personal assumptions about what is possible. If the practice continues, it eventually leads one to direct contact with the unconscious dreaming mind, as well as to an inquiry into spiritual or philosophical questions about the nature of reality.

Waggoner’s five developmental stages are:

Stage 1: personal play, pleasure, and pain avoidance. Initially, most people don’t understand how much power they actually have in their lucid dreams, and so they mistakenly assume that the same restrictions in waking reality apply to the dream realm. One functions at this level by simply seeking out pleasurable experiences and avoiding painful ones, while marveling at the extraordinary sensations in this new world: Wow, I’m awake inside of a dream!

Stage 2: manipulation, movement, and me. At this second stage you begin to understand that you can influence what happens in your dreams through your intention and willpower. This is when you come to understand that you have amazing superpowers in this new environment, and that the laws of dream physics respond to your expectations: Wow, I can fly through walls!

Stage 3: power, purpose, and primacy. This is the stage that unfolds when you begin to gain mastery over the general direction of your dreams and start carrying out systematic experiments to determine what is possible and what the limits of this world are: Wow, I can change the entire dream environment and make anything appear!

Stage 4: re-reflection, reaching out, and wonder. This stage of development emerges when a dreamer learns how to directly address and communicate with the larger dreaming mind, the unconscious: Wow, I can speak directly with the mind behind my dreams and get answers to my questions!

Stage 5: experiencing awareness. This ineffable, ego-transcending stage emerges when you seek out the foundation of consciousness at the core of the dream, and then experience nondual awareness beyond the dream: Wow, “I” don’t really exist!

Walter Evans-Wentz (1878–1965), an American anthropologist and scholar of Tibetan Buddhism whose writings helped transmit Buddhism to the West, described these stages similarly, albeit a bit differently:

The yogin is taught to realize that matter, or form in the dimensional aspects, large or small, and its numerical aspects, of plurality and unity, is entirely subject to one’s will, when the mental powers have been efficiently developed by yoga. In other words, the yogin learns by actual experience, resulting from psychic experimentation, that the character of any dream can be changed or transformed by willing that it shall be. A step further and he learns that form, in the dream-state, and all the multitudinous content of dreams, are merely playthings of mind, and, therefore, as unstable as mirage. A further step leads him to the knowledge that the essential nature of form and all things perceived by the senses in the waking-state, both states alike being sangsaric [i.e., samsara, the repeating cycle of birth, life, and death]. The final step leads to the Great Realization, that nothing within the Sangsara is or can be other than unreal like dreams.12

For many people the initial lure of lucid dreaming comes from the desire to engage in fantasies and thrills, like flying and sex, and many people never develop past this phase into the higher stages. However, some people learn to ignore the superficial elements of the dream and interact directly with their personal (or the collective) unconscious.

SPEAKING TO THE DREAMING MIND

Perhaps the most valuable activity to carry out in a lucid dream has only been mentioned in passing thus far in this book and has yet to be discussed fully. I am speaking here of interacting with the invisible agent orchestrating the dream environment, characters, plot, and action behind the scenes: your “conscious unconscious,”*53 Brahman, Morpheus, or whoever or whatever it is that shapes our dreams. By deliberately addressing the dream environment itself with questions, one can explore one’s unconscious in an uncannily direct way.

As we’ve learned, it’s a common misconception that lucid dreaming means that one can control one’s dreams. Being lucid just means that you’re awake in your dreams and can influence what happens. However, no matter how much creative influence you can have on the structure of your dream characters and environment, there will always be an element of surprise, there will always be things going on that you didn’t intend, and there is simply no way that you can imagine all of the details so quickly when influencing a lucid dream such that you can control every aspect of it. Clearly, there is some other agency or intelligence (or mechanism) operating behind the scenes here, and whatever it is, we can learn to communicate with it directly.

I learned about this ingenious technique from Robert Waggoner, who writes:

Some experienced lucid dreamers . . . maintain that the potential of lucid dreaming includes communicating with another layer of inner awareness. These lucid dreamers report using a counterintuitive technique of ignoring the dream figures and objects, and lucidly addressing questions or requests to a nonvisible awareness behind the dream. . . . The fascinating responses and interactions with this inner awareness appear to meet the characteristics outlined by . . . Jung as necessary to show that a “subject, a sort of ego” exists within the “unconscious.” . . . Approached thoughtfully, lucid dreaming appears to allow lucid dreamers to engage this second psychic system, or inner layer of awareness. If true, this discovery could radically alter the future of psychology and science.13

When I interviewed Waggoner I asked him how he first discovered this technique, and if he was surprised to get a response the first time he directly addressed the dream itself. He replied:

You know, I was astounded to get a response. What happened was . . . in the mid-1980s I became part of a lucid-dreaming group that corresponded each month, and all of us had a monthly goal. One month the goal was to find out what your dream figures represent when you become lucidly aware. So that month I was off on a business trip in Chicago. I went to sleep that night remembering that I had that goal to achieve in a lucid dream. I became lucidly aware, followed someone into an office setting, and I looked around. There were four people there—a receptionist woman, a woman sitting at a table reading a magazine, another well-dressed woman in a corner, and this kind of avuncular older gentleman to my left in a three-piece suit. So lucidly aware, I stepped up to him and said, “Excuse me, what do you represent?” Then it surprised me that instead of him responding, a voice boomed out from above a partial response. The partial response didn’t make total sense, so I just asked the awareness up there to clarify it, and then a full answer came forth. So in the morning I thought, Why didn’t the dream figure respond? Why did this voice boom out, from above the dream figure, the response? So after that I decided that I was going to experiment with this and see if there’s an awareness behind the dream, if there’s a larger consciousness that exists within the dream state—because so often in our life we’re taught to focus on other people, other figures, other creatures, other objects. It’s rare that you would focus on just space, or an awareness that has no visible form.

One can also use a variation of this technique that was developed by Ed Kellogg.14 Kellogg suggests first finding a blank piece of paper or a closed furniture drawer in the dream. Then you ask the question you have in mind out loud, turn away for a few seconds, and then read the paper or open the drawer to see the dreaming mind’s written response. Note, however, that written words are notoriously unstable in lucid dreams. If you’d like to try Kellogg’s technique in a lucid dream, I suggest reading the response quickly and not looking too long at the words, as they typically will start to change when you do.

As I’ve mentioned throughout this book, I’ve experimented with Waggoner’s technique numerous times and have had some good results with it. During my first attempt to do this in a lucid dream, I had the following experience:

After achieving lucidity in the dream, I walked into a small room lined with tiny shelves, from floor to ceiling, that were filled with row after row of cute and artistically designed toys and little sculptures. When I first entered the room I was looking for other people or a wise being to speak with, but there was no one there. Then I remembered that I had wanted to try speaking to the dream itself. However, when I tried this I ran into some difficulty. I tried to say my question out loud, but I couldn’t get the sound out of my mouth for some reason. I tried doing this over and over a few times, and then, finally, I was able to just barely pronounce a few words to my surrounding dream environment. I asked, “What does this dream mean?” Then a few seconds later I heard a barely audible voice, with lots of static and electronic-sounding interference, like from an old transistor radio with a weak signal, coming from somewhere behind me in the room. The voice simply said, “Look.” So I looked more closely at the rows of colorful little toys around me. There were these tiny purple teddy bears dressed in enchanted wizard hats, and dozens and dozens of other little magical objects. I wasn’t sure what the message that I was supposed to see was, and I soon awoke.

After awakening it occurred to me that the lucid dream seemed to be showing me that it was possible to establish a more direct communication link with my conscious unconscious but that the connection was weak and needed to be strengthened. With time and practice I was able to do this, and I received fascinating responses by asking the dream to “astonish me,” “show me the details of what traumatized me at the age of three,” and “show me what you think I need to see.” I’ve also had fruitful interactions when asking for assistance with various creative projects, which is something that a lot of people seem to report success with.

Another good request is to have the dream show you what a mystical or spiritually transcendent experience is like. With some practice, this orchestrating intelligence behind your dreams can become your personal genie in the dream realm as well as your spiritual advisor. I use this technique like an oracle and take my most important questions to it. I don’t always get answers to my questions right away, as sometimes the answers will come in future lucid dreams, but I often get responses that affect me in profound ways. However, I usually get a response around five or ten seconds after asking the question. One time I asked the dreaming mind what it thought I needed to hear, and I opened up a box, expecting to find a piece of paper inside with a note written on it. Instead I found that there was a huge stack of papers inside, with endless notes written on the pages. I wasn’t able to remember any of the written words upon awakening, but I got the message that my conscious unconscious sure had a lot to say to me!

Speaking to the mind behind the dream seems similar to setting an intention or asking a question before embarking on a psychedelic journey. Writing down a question or specifying one’s intention before an ayahuasca or mushroom voyage will often lead to very direct answers or guidance during the experience. Something inside of us listens when we ask these questions, it seems, and when we’re in the right state of consciousness we can divine responses and wisdom from this oracle within.

Who is this mysterious orchestrator of our dreams that responds to our inquiries? Maybe it’s not a single voice; perhaps it’s a collective of sorts. I’m not convinced that the same voice is always responding to my inquiries in every lucid dream. When I interviewed Ryan Hurd about this, he said, “Is it one thing, one system in the unconscious? I doubt it is one thing. There’s really no guarantee that you are in conversation with your higher self when you ask a question beyond the dream. The voice could be representing any number of self-constructs, or even your expectation of a conversation with your higher self. It can be tricky. But the practice certainly brings novelty into the dream, that’s for sure.”

Sometimes it seems as though our responsive unconscious mind has a sense of humor. Consider the following, from Buddhist scholar and lucid-dreaming teacher Charlie Morley:

I remembered my dream plan and put it into action. I called out to the dream: “What is the essence of all knowledge?” Instantly, a huge game show–style computer screen manifested in front of me with the question written across it in big digital lettering. The letters were so big that I could read them easily without them blurring. Three dots appeared after the question mark, indicating that I was about to receive the answer. I tried hard to keep my excitement under control but it was really difficult! Then the answer finally manifested. The computer screen read: “The essence of all knowledge is? . . . Obtainable through lucid dreaming.”15

Morley also discusses a technique that I’ve found helpful—calling out to the dream and asking it to stabilize lucidity. This can help give you more time in the lucid dream to explore its mysteries.

Perhaps the most profound mystery of all that one can seek some illumination on through lucid dreaming is what happens to us when we die.

DREAMING AND DEATH

Around five hundred years ago English playwright William Shakespeare wrote in Hamlet, “To die, to sleep, To sleep, perchance to Dream; Aye, there’s the rub, For in that sleep of death, what dreams may come . . .” These immortal lines draw our attention to the possibility that dreaming may offer us a window into the afterlife.

The ancient traditions of so many cultures speak of dreaming and death together, proposing that the dreaming process offers insight into what happens to us after we die. There are countless examples: We know that Tibetan Buddhism offers profound techniques in dream yoga, regarded as training for death and beyond. Russian psychiatrist Olga Kharitidi, in her book The Master of Lucid Dreams, says the primary tool used by the shaman-healers of Central Asia is lucid dreaming, which the shamans equate with death. In Thomas Mann’s wonderful 1927 novel The Magic Mountain, the protagonist, Hans Castorp, resolves his questions about the mysteries of life and death by means of his experiences with lucid dreaming. The Sanskrit word Vsvap means both “to sleep” and “to be dead,” and this is the root of the English word dream.16 The Dunne-za people of the Doig River region of British Columbia believe that their prophets are able to “transverse the trail to Heaven at will in their dreams,” which they equate with a pathway to the afterlife.17

I tried exploring this timeless philosophical mystery in a lucid dream once. I reasoned that if I could commit suicide in a dream (without really harming myself), then I might be able to gain some insight into what actually happens to consciousness after death. I have this suspicion that a part of me already knows what happens to us after we die, despite my inability to consciously access this knowledge. So, after thinking about this possibility, the next time I found myself in a lucid dream I decided to give it a try. One night in 1999 I had the following experience:

I was being pursued in a large warehouse by some threatening figure in the dream when I became lucid. I found a private section in the building that I was in, and after repeatedly confirming that I was indeed dreaming— more so than usual, as there was no room for error—I conveniently found a handgun located in my right hand. I pointed the gun at the side of my head, took a deep breath, and bravely pulled the trigger. After the bullet fired, the next thing I knew I was bodiless, in a dark, silent void, alone with just my thoughts. It wasn’t unpleasant, but it was certainly much less dramatic than what I was expecting, and I soon awoke.

There was no tunnel, no bright light, no loving presence, or any sense of special peace; it was just my consciousness, alone in a dark, silent void. After reflecting on this experience, I now suspect that this wasn’t necessarily my unconscious mind’s vision of death so much as its vision of death by suicide. In reading about the near-death experiences of others, it seems that most people have positive encounters when they begin to depart from life, with one primary exception: when suicide is attempted. This is when hellish experiences are often reported, and one of these hellish NDEs is being alone in a dark, silent void (although my experience in the dream wasn’t this unpleasant).

I wasn’t the only one who tried to commit suicide in a lucid dream, however I was one of the more successful. The Marquis d’Hervey de Saint-Denys recounts how he also tried to commit suicide in lucid dreams but always ran into obstacles that prevented him from succeeding in his attempts. In one experience he tries to cut his own throat with a razor, but his “instinctive horror of the action” prevents him from carrying this out, and in subsequent lucid dreams, when he considered shooting himself, he reports that locating and operating a pistol in the dream always took too long.18

In Celia Green and Charles McCreery’s book Lucid Dreaming: The Paradox of Consciousness during Sleep, the authors provide several more examples of people who tried to commit suicide in lucid dreams but were also unsuccessful, as the dream faded or they awoke when they tried crashing a van or jumping under some moving cars.19

However, there are also reports of people having near-death experiences in nonlucid dreams that differed from my experience within a lucid dream. I’ve read a number of accounts of people who died in their dreams as a result of accidents and then had OBEs and transcendent spiritual experiences, all within the dream, but they weren’t lucid.

When I asked Stephen LaBerge what he thought about consciousness after death, he said this:

Let’s suppose I’m having a lucid dream. The first thing I think is, Oh, this is a dream, here I am. Now the “I” here is who I think Stephen is. Now, what’s happening in fact is that Stephen is asleep in bed somewhere, not in this world at all, and he’s having a dream that he’s in this room talking to you. With a little bit of lucidity I’d say, This is a dream, and you’re all in my dream. A little more lucidity and I’d know you’re a dream figure and this is a dream table, and this must be a dream shirt and a dream watch and what’s this? It’s got to be a dream hand and well, so what’s this? It’s a dream Stephen! So a moment ago I thought this is who I am, and now I know that it’s just a mental model of who I am. So, reasoning along those lines, I now think I’d like to have a sense of what my deepest identity is, what’s my highest potential, which level is the realest in a sense. With that in mind I have this lucid dream in which I am driving my sportscar down through the green, spring countryside. I see an attractive hitchhiker at the side of the road, think of picking her up but say, No, I’ve already had that dream, I want this to be a representation of my highest potential. So the moment I have that thought and decide to forego the immediate pleasure, the car starts to fly into the air and disappear, and my body too. There are symbols of traditional religions in the clouds—the Star of David and the cross and the steeple and Near Eastern symbols. As I pass through that realm, higher, beyond the clouds, I enter into a vast emptiness of space that is infinite, and it is filled with potential and love. And the feeling I have is This is home! This is where I’m from and I’ d forgotten that it was here. I am overwhelmed with joy about the fact that this source of being is immediately present, that it is always here, and I have not been seeing it because of what was in my way. So I start singing for joy, with a voice that spans three or four octaves and resonates with the cosmos, in words like “I Praise Thee, O Lord!” There isn’t any “I,” there is no “thee,” no “Lord,” no separation somehow, just a sort of “Praise Be!”

My belief is that the experience I had of this void is what you get if you take away the brain. When I thought about the meaning of that lucid dream I recognized that the deepest identity I had there was the source of being, the all and nothing that was here right now, that is what I am too, in addition to being Stephen. So the analogy that I use for understanding this is that we have these separate snowflake identities. Every snowflake is different in the same sense that each one of us is, in fact, distinct. So here is death, and here’s the snowflake, and we’re falling into the infinite ocean. So what do we fear? We fear that we’re going to lose our identity, we’ll be melted, dissolved in that ocean and we’ll be gone. But what may happen instead is that the snowflake hits the ocean and feels an infinite expansion of identity and realizes what I am in essence— water! So we’re each one of these little frozen droplets and as such we feel only our individuality, but not our substance. But our essential substance is common to everything in that sense, so now God is the ocean. So we’re each a little droplet of that ocean, identifying only with the form of the droplet and not with the majesty and the unity. There may be intermediate states where, to press the metaphor, the seed crystal is recycled and makes another snowflake in a similar form or something like that, but that’s not my concern. My concern is with the ocean, that’s what I care about. So whether or not Stephen or some deeper identity of Stephen survives, well, that’d be nice if that were so, but how can one not be satisfied with being the ocean?

Additional evidence that dreams might serve as a portal into what happens to consciousness after death comes from encounters that people have reported with deceased loved ones in their dreams.

COMMUNICATING WITH THE DEAD

Many people have reported having meaningful contact experiences with friends and family members who have died in lucid and non-lucid dreams. Sometimes practical information is passed along in these encounters, as in the case of poet and painter William Blake (1757–1827), who dreamt that his deceased brother taught him an engraving technique that he used after the dream.20 Other people have resolved conflicts, finished uncompleted dialogues, and also exchanged personally meaningful information in dream encounters.21 When I interviewed psychologist Stanley Krippner, who has studied dreams like this for many years in great detail, he said, “There are numerous examples of what I call ‘visitation dreams,’ and I doubt that all of them can be written off as coincidence, prevarication, or wish fulfillment.”

Psychologist Patricia Garfield wrote a fascinating book on this topic, The Dream Messenger: How Dreams of the Departed Bring Healing Gifts. Garfield writes,

Sooner or later, all of us will have to endure the trauma of the death of a significant person in our lives. . . . Regardless of your beliefs about whether there is an afterlife or not, one thing is certain: you will dream about the person who recently died. . . . Whether these dreams are actual contact with spirit or images conjured up by our own needs is not the issue: what we know is that we dream about the people we have lost, and that these dreams are extraordinarily vivid and emotionally charged and can alter the life and belief system of the dreamer. In the dream world, unfinished dialogues can be completed and conflicts resolved.22

I’ve personally had some beautiful, heartwarming encounters with friends and loved ones who have passed on in lucid dreams. The late psychiatrist Oscar “Oz” Janiger, the friend who introduced me to Stephen LaBerge and the scientific study of lucid dreaming—and was the psychiatrist who treated me for depression—has appeared in quite a few of my lucid dreams. In one particularly striking one, Oz and I walked around arm-in-arm in this beautiful utopian village. He explained to me that this was where he was now living. My memory of that encounter with Oz, which occurred a few months after he died, is as real and vivid as any memory that I have of him from waking life, and it affects me in a deeply emotional way, although, of course, that doesn’t necessarily mean that it was real.

I also once had a nonlucid dream as an adult where the cat from my childhood, Fritzy, had somehow come back to life. She was really old and fragile in the dream, but I was overjoyed to see her again. The dream left me feeling really happy when I awoke.

My girlfriend told me about a lucid dream that she had one morning, in which she met up with her father who had passed away several years earlier. She described becoming lucid in the dream while looking at the stars in the sky, after which a woman pointed to the door of a bar and said, “You’re going to miss your chance.” Rebecca walked over to the bar and . . .

I pulled the door handle, looked around inside, and saw a few people chatting and playing pool. There was a big group of people by the bar. No one seemed to notice that I walked inside or paid any attention to me as I walked in the room. I walked to the side of the wall where the pool sticks were kept. I picked up a pool stick and couldn’t get over how real it felt in my dream hand—the weight of it and all the textures were just like waking life. I walked around toward the back of the pool hall, carrying my pool stick with me, to where there were fewer people, and I was trying to decide which table I wanted to play on. I picked one, bent down to get the balls out from under the table, and realized that I didn’t have any money for the quarter slot. Luckily, I’m in a dream, so I don’t need any money, I thought. I used my fingers to turn the metal lock on the case that the balls were in and started putting them on the table. As I was doing this I noticed someone standing on the other side of the pool table. I looked up and . . . it was my dad! I was stunned and felt like my heart was going to explode with joy! (And to be honest, I felt a tad bit of fear, because I know that in waking reality my dad has passed away.) “Don’t look at me like that—we going play or what, girl?” he said. “Girl?” Yup, that’s my dad, no question about it. From there we played a game of pool. I was shooting the balls in left and right. My dad was really impressed, I could tell by his expression. I was making almost every shot, Dad really didn’t even have that much of a chance to play. Toward the end of the game I shot a ball and it bounced off the table and rolled into a dark room. Inside the dark room sat a Christmas tree with a lot of gifts underneath. As my dad walked over to the room, he said, “You are getting good, girl, real good!” and he started looking for the ball. As I was sitting there waiting for him to come back, I woke up.

My favorite passage in Garfield’s book comes from someone who had the following experience about encountering a deceased relative in a dream: “I am astounded to see my dead uncle alive again, singing, laughing, and making jokes; I say, ‘My God, what are you doing here? You’re dead!’ He smiles and replies, ‘Honey, when you die, you lose your body, not your sense of humor.’”23

Within death lies the deepest of mysteries, and biological termination gives meaning to life—but maybe there is consciousness beyond life and death . . .

MYSTICAL EXPERIENCES AND NONDUALISTIC CONSCIOUSNESS

As I previously mentioned, it seems that persistent lucid dreamers will eventually report having spiritual, religious, or mystical experiences within their lucid dreams. This propensity for fostering mystical experiences is a common feature that lucid dreams share with psychedelic or shamanic states of consciousness.

A mystical experience is often described as a state of nondualistic awareness. In this ineffable state, conceptual opposites unify and personal boundaries dissolve in an all-encompassing reunion with the bedrock of consciousness. During a mystical experience the distinctions that separate one’s awareness from the rest of the world melt away, the ego vanishes, and there is a profound sense of interconnectedness with all of existence, which many people describe as orgasmic. In lucid dreams you achieve this state when you move into what is beyond or behind the dream itself. When I interviewed Ryan Hurd he attempted to describe his experience in this state of consciousness:

About eight years ago . . . I woke up in the middle of the night into a nondual experience that felt a lot like cosmic love as I hear other people describe it. I shared a flow of energy that was bigger than me. I was part of it, but it was also separate from me, and we were . . . but it was . . . I was . . . Ugh—there’s just no words! You try to get into it and it all just falls apart. It was heart-centered, it was glorious, confusing, and I just did not exist as I now define myself. But I would not call that a lucid dream, it was something else entirely. I mean, from a technical standpoint, a lucid dream has to be dualistic, you have to have a witness for metacognition to take place, to know that you’re dreaming.

Fig. 10.1. Lucid-dream researcher Ryan Hurd (photo by Brian Furry)

In 2006, investigators at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine published the results of a six-year project on the effects of psilocybin, in which more than 60 percent of the participants reported having had “complete” mystical experiences. These experiences were rated as being among the most personally meaningful and spiritually significant of their lives, and they were indistinguishable from the reports of religious experiences by mystics throughout history.24 Recall that earlier we learned that psilocybin’s action mimics some aspects of conscious dreaming in the brain.

A study done by psychologist Fariba Bogzaran, founder of the dream-studies program at John F. Kennedy University, demonstrates that merely expressing the intention of wanting to have a spiritual experience in a lucid dream can lead to actually having one.25 According to Bogzaran, practicing intention and incubation prior to sleep are the two most important factors in cultivating spiritual experiences in a lucid dream. In another study done by Bogzaran she describes the difference between ordinary lucid dreaming and “multidimensional dreams” or what she refers to as “hyperspace lucidity,” where lucid dreamers report experiencing a transformation of their dream bodies into particles of light, or when the dream body disappears while awareness continues.26

I’ve had many mystical experiences in both psychedelic states of consciousness and lucid dreams. As a teenager, the combination of LSD, nitrous oxide, and reading the work of philosopher Alan Watts activated full-blown religious experiences within me that kick-started my spiritual development and deeply influenced the course of my life. Likewise with lucid dreams. I’ve had deeply moving, profoundly transformative mystical experiences when, for example, within a lucid dream I sat down, closed my dream eyes, and simply started meditating. It seems that all that is necessary to have spiritually illuminating experiences within a lucid dream is the intention to have such experiences.

Consider the following lucid dream I had one morning while writing this book. It began with my persistent sexual pursuits, resulting in the first time that I ever actually achieved realistic sexual intercourse within a lucid dream, as for many years something always prevented me from doing this. Although the pleasurable sexual encounter appeared to contain a punch line of sorts, the dream ended with a powerful spiritual experience:

I finally succeeded in actually having realistic sex in a lucid dream—well, sort of. I found a willing partner but had some trouble getting all of her clothing down past her butt. She was on all fours, sticking her butt out and wiggling it, but there were so many layers of clothing to pull down—four or five layers of pants, pantyhose, underwear. I finally got them all down, got an erection, and entered her. Once I was inside of her it feltwonderful and completely real. I was really enjoying the delightful sensations, knowing that my time there was limited, and I was trying to see if I could actually orgasm in the dream. However, before I could come, the woman turned into a rubber doll. Actually, she became just a partial, life-size doll’s body, just the backside and butt, made out of rubber or latex, and she was hollow, there was no front to her. I realized with a sudden shock that I was just having sex with this rubber thing. Then I realized that I wasn’t alone in the room, which was a classroom of sorts. I noticed that a little boy was sitting in a chair watching me trying to have sex with this doll of a partial woman. Despite being lucid and knowing that I was dreaming, I couldn’t help but feel embarrassed. This little boy then became part of another child; they seemed biologically connected somehow, and they didn’t seem too concerned with what I had been doing with the rubber doll. Most interesting of all was my encounter with a different little boy whom I met later in the lucid dream in the upstairs bedroom of an unfamiliar house, who was around five years old. I was thinking that I was going to ask him about his dreams. I wanted to ask the dream characters in my dreams about their dreams! Then, at the exact same instant in time, we both asked each other, “What are your dreams like?” I was really surprised by this simultaneous expression, and I said to him, “How did you know that I was going to ask you that?” Then he looked at me with an expression of wisdom that I’ve never seen another dream character possess and confidently said, “It’s because we’re the same person.” I was utterly shocked that he knew this, as I’ve never had a dream character say that to me in a lucid dream before. Usually it’s me telling them that we’re the same person. I asked him how he knew this, and his face became more animated, cartoonlike almost, and he said something that seemed very wise and funny, that seemed to contain these clever puns and have multiple meanings, but I can’t remember what he said or even if I fully understood what he was saying at the time he said it. After he told me this I closed my eyes in the bedroom with the little boy, raised my head toward the ceiling, and asked the dream intelligence to show me the “highest spiritual experience.” Then “I” simply dissolved into an egoless, light-filled awareness, before I awoke.

This brightly lit, nondualistic awareness that I experienced in my lucid dream is sometimes referred to as the “void.”

THE VOID

The term void describes a type of nondualistic awareness that can be reached in lucid dreams and other shamanic states of consciousness. It transcends both the physical world and the dream world and is sometimes distinguished from other types of nondualistic states of consciousness. It seems that the term can actually have several meanings, although it generally implies a state of mind or a purity of awareness that lies beyond the perception of separation or form.

In a personal communication, New Zealand–based lucid-dream researcher Peter Maich sent me his description of this state:

I feel there are two places that dreamers call the void. The first is in the early stages of a wake-induced lucid dream, when you drop or phase to a light sleep state and retain awareness of this state change. At this point it gets eerily quiet as the sense of hearing is the first to shut down, and you can be in a darkness that feels like an open space that will often precede hypnogogic imagery. The second place is entered from within a lucid dream, and I describe this as the space between dreams. In the early days I would enter this space and quickly transit to a new dream. Now I am able to spend time there and see it as a place of its own, with potential for adventure.

I found Maich’s experiences intriguing. He describes at first feeling uneasy in the second type of void, with its dark, formless space (reminiscent of the state I experienced after committing suicide in a lucid dream, only this state appears liberating whereas mine felt confining). But then in time he becomes comfortable enough to explore: “Over a series of dreams I’ve had a lot of entries into the void and found that if I just accepted being there I would remain for longer periods. In time I also started to lose the uneasiness that seemed to accompany me at first. The more time I spent in the void, the more I seemed to lose any sense of self, and it got to the point where I felt I existed as pure awareness.”

It seems that the void is an egoless state of awareness, beyond the body and all form. However, it appears that descriptions of it, even using the distinctions that Maich made, don’t always match up: my own experience of the void was filled with light, while Maich experienced darkness or emptiness. It appears to be inherently difficult to describe this experience using language, which is based upon the perception of distinctions. Nevertheless, Maich writes:

In the void there is blackness that seems to be all around and has a presence. It is not seen with eyes, but experienced with a set of inner senses that combine to create the awareness. This awareness is very hard to define in normal terms. There is nothing to touch, and I have nothing to touch with, as there is no energy or dream body either. There is thought and full access to memory and the ability to leave to another dream if desired. I suspect what is happening is a shutdown of all sensory input and no recall of sensory data to construct a dream with.

When I interviewed Robert Waggoner, he described his own unique experience of the void: “I began to fall asleep at night, and the entire night there’d be nothing but blue light. So there were no figures, no symbols, no action, no plot, no me. It was just blue light.” Descriptions of the void often seem reminiscent of the goal of Tibetan dream yoga, which is to reach what is called the “clear light,” a nondualistic state of mystical consciousness. Ryan Hurd describes his experience with the indescribable like this:

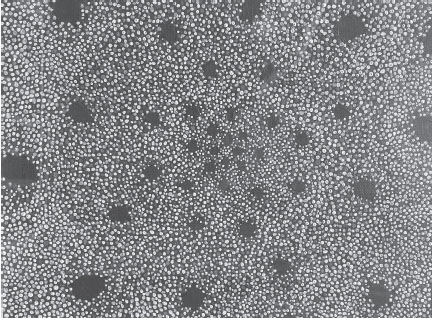

Since I was a child I have had conscious dream experiences that take place in immense, spacious realms devoid of light or objects. Sometimes these spaces are truly voids and my own dream body does not exist. Other times these spaces become filled up with abstract geometric patterns, or multicolored buzzing particles that resemble the “snow” from a television set. I call this the “cosmic snow” because it is literally the stuff dreams are made of.27

I’ve experienced this state of consciousness, or something similar, after inhaling the vapors of 5MeO-DMT, which is chemically similar to, but phenomenologically different from, N,N DMT, which is the type of DMT that I’ve been referring to throughout this book. Both compounds are naturally found in the human body. People often report seeing an insane multitude of endlessly morphing, multihued forms and hyperdimensional alien worlds after ingesting N,N DMT, but after ingesting 5MeO-DMT, the most common report is that of being immersed in a bright white or clear light. It’s as though these two basic forms of DMT represent the all and the void, everything and nothing.

In psychonaut Zoe7’s book Back from the Void, the author describes the void as “a primordial point of origin as well as a point of extinction. It is the Alpha and the Omega—a way station for recycling soul and all of Creation. The Void can be thought of as an ‘instance’ in which nothing exists. It’s a point when All That Is was not.”28

Fig. 10.2. Entoptica, a painting by Ryan Hurd based on his lucid “void” experience

From this description it seems like the void might be a good place to visit if one wants to begin fresh and start anew. Dissolving into the void and reemerging involves a kind of death and rebirth of the ego or personality. So when I needed to reorganize my life from the ground up, that’s just what I did, and this book encapsulates my healing journey, transforming years of misunderstood pain and confusing darkness into newfound strength and guiding light.

BIOCENTRISM AND AYAHUASCA

Biologist Robert Lanza presents a theory in his book Biocentrism that may provide some important insights into the nature of reality and dreaming. Lanza proposes that the universe is actually created by the perceptions of conscious, living creatures. He turns the whole notion that life evolved from an inanimate universe on its head, by interpreting the results of experiments in quantum physics in a direct and practical manner and suggesting that the physical universe evolved from life, consciousness, and observation, not vice versa.

If reality requires observation to exist, then how could a universe without observers ever have evolved? asks Lanza. He suggests that this is why everything in existence fits together so perfectly—why the whole universe seems to be so perfectly designed just for us, why all of the improbable cosmic factors seem so precisely orchestrated for our arrival: because we created the universe through life’s observations, those moment-by-moment acts of choosing one possible event out of the always infinite availability of quantum-possibility waves.

I realize that this sounds paradoxical on the surface, and I can’t summarize all of the details of Lanza’s fascinating theory here, but I bring it up because the combination of reading Biocentrism and doing ayahuasca in the Amazon transformed my life in such a way that I can only say that I feel like I’m always living inside of a lucid dream when I’m awake, or inside a model within my own mind. These two factors conspired to turn my worldview inside out. While I conceptually understood for many years that I wasn’t actually experiencing the “real world,” and instead was experiencing a mental simulation of the world, it wasn’t until I did ayahuasca and read Lanza’s book that something clicked in my mind, and this knowledge suddenly became clearly experiential. I now experience the world as being inside my mind, instead of my mind being inside the world. It’s difficult to explain how this conceptual shift occurred, because I realize that every time I try to explain it, it sounds like I’m saying something that I already knew before the conceptual shift occurred, and many other people already know, which seems obvious. All I can say is that something shifted inside me that made this knowledge experiential in a way that I hadn’t ever realized or anticipated before.

I’ll do my best to explain what happened. Up until this shift occurred, despite what I already knew, it always appeared that I was inside a body-brain system, looking out at the world through the windows of my senses. Now, I knew from studying neuroscience and taking LSD that I wasn’t directly seeing the world around me, but rather viewing a simulation of reality created by my visual cortex from a sea of electrical signals. I already knew that the world exists inside my mind, not vice versa—but I wasn’t experiencing it that way.

The model of myself that I naturally had in my head was completely backward. I wasn’t looking out at the world through the windows of my senses; I was experiencing a simulation of the world inside my mind. This means that, like in a lucid dream, everything around “me” (including what I thought was my body) isn’t the (directly unknowable) physical world (or my body), as I had thought my whole life, but rather the inside of myself. The reason why consciousness may survive death—and anything is possible—is because on the level of our subjective experience, which is all that we ever really know, the universe exists within our own minds.

All that exists in everyone’s experience of this universe is consciousness and its contents. What we think of as our bodies and the world are actually concepts inside our minds. The most consistent, constant image, in both dreaming and waking states of consciousness, is the image of one’s body. So ubiquitous is this image that we normally take it for granted, without regarding its true nature. But it’s important to understand that the image of one’s body is not equivalent to a physical body; rather, it is a concept created in one’s mind. Gaining this perspective is tremendously liberating, and with it comes the ability to psychically influence the world and manifest synchronicities within reality to a greater degree. Everything is interconnected because everything is inside our minds. While obviously not as pliable as a dream, physical reality is much more responsive to our thoughts than many people realize. It may be that physical laws are themselves mental constructs within a larger, more universal mind. The best metaphor for understanding this shift that occurred in me is by saying that now it is like my whole life is happening within a lucid dream. Whatever I do and wherever I go, it’s clear that I’m always inside the center of my own mind. I think that what I’ve been experiencing is what some people refer to as “lucid living.”

According to Tibetan dream-yoga master Tarthang Tulku, once one realizes that life is like a dream, in the sense that all experience is subjective and we never directly experience an objective world, then our self-identities become less rigid and “even the hardest things become enjoyable and easy. When you realize that everything is like a dream, you attain pure awareness. And the way to attain this awareness is to realize that all experience is like a dream.”29

THINKING OUTSIDE THE MATRIX

Okay, here’s a thought experiment: Imagine that you wake up tonight inside a dream. Ah, wonderful! you think, so excited to be lucid while dreaming, wondering what you’ll do next and how you’ll sustain the dream. Then let’s say you’re able to indulge in all of your wildest fantasies, live like a deity, and the dream lasts and lasts. You’re just marveling at how awesome all this is when you start to realize how strange it is that you still haven’t woken up. So you have some more fun and then start to think that it really is time to get back to your body and waking reality, when you realize that you can’t. Nothing you do to try to wake yourself up works. Maybe your body is in a coma, or perhaps you’ve died, but whatever the case, you now find that you’re stuck inside your dream.

Now imagine that you just start living your life from within this dream world. Days and nights go by, and soon you want to start discovering the nature of this new reality, so you become a scientist in the dream. You observe everything carefully and carry out experiments. You make discoveries about the nature and limits of this world, and you start to think that you’ve gained some kind of an understanding of this reality—until you remind yourself that every measurement and calculation that you make in this reality is done using measurement tools that are composed of dream matter. Every act of measurement is actually made using . . . what? A mental concept, not anything material. And then everything that is actually being measured is also just a mental concept. It suddenly occurs to you that aside from your own existence, nothing else can be perceived with any certainty, because everything that you can sense is composed of your own mind. Now, how would this situation differ from the situation that we find ourselves in right now, here in waking reality, I wonder?

This thought experiment leads to a similar state of philosophical confusion, about what level of consciousness or reality we actually exist in, as an ancient Hindu myth about a hunter and a sage, from the Yogavasistha Maharamayana of the harbinger-poet Valmiti, a philosophical treatise and compendium of dream narratives that dates back to as early as the first millennium. I discovered this remarkable story around six months after writing the thought experiment above. In this story within a story, a demon goes through various incarnations as different insects and animals before incarnating as a human being who is a hunter. The hunter wanders through the woods and comes upon the home of a sage, who becomes his teacher and tells him the following story:

I studied magic. I entered someone else’s body and saw all his organs; I entered his head and then I saw a universe, with a sun and an ocean and mountains, and gods and demons and human beings. This universe was his dream, and I saw his dream. . . . I saw his city and his wife and servants and his son. When darkness fell, he went to bed and slept, and I slept too. Then his world was overwhelmed by a flood at doomsday; I, too, was swept away in the flood. . . . When I saw that world destroyed . . . I wept. I still saw, in my own dream, a whole universe, for I had picked up his karmic memories along with his dream. I had become involved in that world and I forgot my former life. . . . Once again I saw doomsday. This time, however, even while I was being burnt up by the flames, I did not suffer, for I realized, “This is just a dream.” Then I forgot my own experiences. Time passed. A sage came to my house . . . and as we were talking . . . he said, “Don’t you know that all of this is a dream? I am a man in your dream, and you are a man in someone else’s dream.” Then I awakened, and remembered my own nature . . . that I was an ascetic. And I said to the sage, “I will go to see that body of mine (that was an ascetic),” for I wanted to see my own body as well as the body which I had set out to explore. But he smiled and said, “Where do you think those two bodies of yours are?” I could find no body, nor could I get out of the head of the person I had entered, and so I asked him, “Well, where are the two bodies?” The sage replied, “While you were in the other person’s body a great fire arose that destroyed your body as well as the body of the other person. Now you are a householder, not an ascetic.”30

After the sage tells this story to the hunter, who is now in a state of amazement, the hunter lies down in bed in silence and says, “If this is so, then you and I and all of us are people in one another’s dreams.”31 Missing the sage’s point, the hunter leaves and goes through more incarnations, finally becoming an ascetic, and eventually achieving liberation.

WHY IS WAKING UP FROM THE DREAM OF LIFE FORBIDDEN?

Due to a consistent (possibly deliberate?) mistranslation of a Hebrew word in the Bible by Saint Jerome in around 450 BCE, seeking guidance through one’s dreams became equated with witchcraft for more than a thousand years, and many authorities in the Roman Catholic Church prohibited dream interpretation.32 Like psychedelic states of consciousness, dreams can seem threatening to those in authority, perhaps because they expand our notion of what is possible.

Funny, isn’t it, that with the advent of electronic dream machines like the DreamLight or the REM-Dreamer, one of the most commonly reported interpretations of how flashing LEDs are incorporated into the dream is as police lights? Sometimes I wonder if it’s against the rules to become lucid in our dreams, or in waking life. Some people seem to think so, and perhaps the band Cheap Trick was on to something in 1979 when they sang, “The dream police, they live inside of my head.”

This book contains secret information that can get you into trouble if used unwisely. In the Book of Genesis (3:5) it is forbidden to eat from the Tree of Knowledge because one’s “eyes will be opened and you will be like God.” As with the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden, I suspect that the real reason that psychedelic plants and drugs are illegal is because they wake us up from the dream of life, and many people are culturally programmed to believe that we should stay asleep.

Life is like a game in many ways, and the first rule of this game of games is to unquestionably accept what your senses tell you as reality. To get along here on Earth, we all need to accept the basic assumption that everything we see, hear, touch, taste, and smell is “real.” Anyone who thinks otherwise is, of course, crazy.

The acceptance that life is actually real is universally experienced and rarely questioned—but how would you know if you were imagining the universe into existence or not? It appears that waking up from the dream of life is an inherently difficult process. It almost seems as though there is a built-in inhibition to discovering this, as though it is a deliberate part of the design of the universe. Perhaps it is. Regardless, there appears to be a huge increase in the number of people in the world today who are interested in lucid dreaming, as well as psychedelic states of awareness, and I suspect that this growing trend will continue into the future. It seems like the whole world is starting to wake up, and perhaps this is part of the overall design that is unfolding too.

STEPPING INTO THE FUTURE

In the 1949 Broadway musical South Pacific, Bloody Mary sings these famous lines, “You gotta have a dream, if you don’t have a dream, How you gonna have a dream come true?”

I find it interesting that the word dream refers both to our nightly adventures in slumberland and to our ideal vision of what we’d like most in our lives. During the process of writing this book about lucid dreaming many of my longtime dreams, of the second kind, surprisingly did come true—with regard to my career, my home, and my romantic partner. Somehow the process of increasing awareness in my dreams brought me greater balance and health, as well as more love and abundance in my life.

After my shamanic healing in the Amazon, the dynamics of my life began to substantially shift, and it was during this period that my lucid dreams began to increase in frequency—which helped inspire me to write this book. It seems that the timing of my personal journey is in synch with the culture at large, which is now exploding with an interest in lucid dreaming, and we’re making enormous scientific advances at an accelerated rate. I think that this interest in lucid dreaming and our understanding of it will grow into a sophisticated science, opening up magnificent new possibilities for our species. Terence McKenna echoed this sentiment when he told me:

I’ve had lucid dreams, but I have no technique for repeating them on demand. The dream state is possibly anticipating this cultural frontier that we’re moving toward. We’re moving toward something very much like eternal dreaming, going into the imagination and staying there, and that would be like a lucid dream that knew no end, but what a tight, simple solution. One of the things that interests me about dreams is this: . . . They are more powerful than any yoga, so taking control of the dream state would certainly be an advantageous thing and carry us a great distance toward the kind of cultural transformation that we’re talking about. How exactly to do it, I’m not sure. The psychedelics, the near-death experience, the lucid dreaming, the meditational reveries . . . all of these things are pieces of a puzzle about how to create a new cultural dimension that we can all live in a little more sanely than we’re living in these dimensions.

I suspect that our species’ interest in lucid dreaming is an extension of our planet’s 4.5-billion-year evolutionary process, and I see consciousness explorers as the leading edge of our biosphere’s emergence into new frontiers. I think these frontiers—the realms of consciousness that we find in our dreams or in shamanic states of mind, and perhaps those that hover beyond death—could be genuine geographical realms, where we can, and eventually will, set up transportation and communication systems.