MANY REASONS HAVE BEEN advanced for the extraordinary run of eleven successive premierships that fell to St George from 1956 to 1966. Norm Provan played in ten of them, and he has his own theories about what made the club special through that time. The foresight and the dogged efficiency that the club administration brought to team-building were a big part of it. The natural bounty of the area in producing champions like Provan himself, Reg Gasnier and Billy Smith was also crucial. But there was a tactical and strategic element too, built around the English experience that Ken Kearney, and later Harry Bath, brought to the club. To Norm Provan, the input of Kearney, later complemented by Bath, was the singular factor that lifted St George above the pack.

Kearney had played four seasons with Leeds in England after completing a successful Rugby Union tour with the Wallabies in which he had been a Test match fixture. He found English Rugby League to be as smart as it was ruthless, and when he joined St George in 1952 he marvelled at the different approaches in the two countries. He found it hard to understand the lack of sophistication in Australian league at the time. It was all one-out, hope-for-the-best stuff, he reasoned, without the tactical nous that had been the bread and butter of English football. He set about changing that. Kearney played eleven games in his first year with Saints, was captain the following year, captain–coach in 1954 and 1955, captain under coach Norm Tipping for the first of the premierships in 1956, then captain–coach until his retirement at the end of the 1961 season.

Bath first played senior Rugby League in Brisbane in 1940, was selected for Queensland, and then moved to Sydney, where he won NSW selection and figured in Balmain premiership sides in 1946 and 1947. He was chosen to play for Australia against England in 1946, but injury cost him a game in any of the Tests. He went off to England, played 346 games in nine seasons with Warrington, and played many times for Other Nationalities, an international equivalent for overseas players domiciled in England. Along the way he captained Warrington to two Challenge Cup titles, kicked mountains of goals, and developed skills above and beyond the norm. He played three seasons with Saints at the end of his career, twice topped 200 points, and was an important cog in three premierships. He retired at 35 to move into a celebrated coaching career. They said he was the best forward never to play for Australia. Norm Provan describes him as simply a genius.

NORM PROVAN

Ken ‘Killer’ Kearney became captain of St George in his second season, but he really started reshaping the club before that. Killer made no secret of the fact that he didn’t think we trained very well or had any real tactical insight. He reckoned we were all heads down and bums up, without any subtlety in what we did. Ken had played a lot of football in England, where they played a couple of games a week and generally thought a lot more about the creative side of the game. On top of that he thought we were generally ill-prepared. He didn’t think we were fit enough, and he was critical of the happy-go-lucky attitude that was the Australian way in those days, and not just at St George. He brought a very strong discipline to the club that became embedded in the way we operated, and that continued long after Kearney was gone. The thing Killer did most of all was make us serious about winning. He gave us a professional edge long before anybody talked of such things.

When Kearney took on the coaching as well as the captaincy in 1954 he was already the most dominant character in the club. We had come runners-up to Souths in Killer’s first year as captain in 1953, then finished third in the next two years when he was captain–coach. The club’s ultimate success was taking shape in those years. He brought in a trainer in John Gurd, who was a physical education instructor at Sydney Teachers’ College and a good bloke who won the respect of the troops. It sounds strange by today’s standards, I know, but Gurd introduced various programs of circuit training, and it was considered very scientific at the time.

The Saints boys had always trained hard. I ran every day and so did a lot of others, and we pounded away on bush tracks and sandhills, and did sprints until we were sick of them. I hung on to the pair of spikes I had been given in my first season for sixteen years, and all the running I did certainly helped me. But Gurd talked of strange things like aerobics, and the variety of his circuits was designed to prepare us for every facet of the game, not just being able to run for long periods. It worked, and it was enjoyable too. One of the effects of Kearney’s attitude to conditioning was that we all became very competitive among ourselves. That stuck through all of my years at Saints. People like Reg Gasnier and Billy Smith especially would not allow themselves to be beaten at anything, and the most basic training routine to them became a mighty contest. It made Saints the fittest side in the competition.

Kearney, of course, was a fantastic hooker who could fight for the ball in so many different ways that we were all amazed. He wasn’t a dirty player as such. He certainly wouldn’t start anything, and he didn’t want any of the rest of us to go looking for a fight either. But neither would he cop anything. He did some fierce damage to anybody who tried to get over the top of him by unfair means. And he also brought to Saints an emphasis on the value of forward play that was, for all the brilliance of the backs we had, the bedrock of the club’s success.

It was Killer’s way to get on top early in the forwards, even if that meant giving the ball to the opposition for a while. Occasionally he would deliberately kick the ball through the scrum so that Saints could marshall their straight-line defence and hammer the opposition. He called it his softening-up period. He had introduced a defensive line at Saints that was near impregnable, and later on, when we got John Raper flying about the field as a cover-defending missile, that only added to it. I could see Killer’s point in making a weapon of our defence, and you see a lot of it today, although I don’t think the ball is ever conceded. I wasn’t totally in favour of it then, either. It was hard to score tries without the ball, and giving it away just lessened opportunities. The only blot on an unbeaten record in 1959 was a draw against Balmain in which Killer let them have a lot of possession they didn’t deserve, just so he could get stuck into them. Saints rattled plenty of teams playing that game, and I played my part, but I have to say I preferred it when we had the ball.

In 1956, when we won the first of our eleven premierships in a row, Killer lost the coaching role to Norm Tipping, who had been a winger and fullback in his playing days and the previous year had coached the President’s Cup side. They said he got the job because the committee was upset that Killer was having a running feud with Darcy Lawler, who had become the leading referee by then. Kearney was not the sort of bloke who would back down, and neither was Darcy. Unfortunately Darcy had the whistle, and Saints were copping more penalties than was comfortable. Tipping was a good coach, but there was immediate friction between him and Killer. Killer was not happy that he had lost the job, for starters, but he didn’t respect the way Tipping wanted to coach the team either.

Killer wanted to get the forwards right first, and he wanted to base the game on forward control. Norm Tipping was very good at developing tricky moves and all sorts of plays in the backs that often worked very well.We had some real good backs that year, too. But once we were on the field Kearney was in control, and he made sure the forward stuff was right before anything much happened in the backs. There was a lot of tension between them, but we still played some great football, and in the end there was probably a lot of influence from both of them in the way it all panned out.

We beat Balmain 18–12 in the grand final that year. It was Saints’ first premiership in fifteen years, and we won the grand final with twelve men for all but the first thirteen minutes of the game. Our centre Merv Lees, a wonderful player in those early sides, smashed his collarbone early on, and replacements were not part of the game then, no matter how badly injured you were. Billy Wilson had to move to the centres, leaving us a forward short. It didn’t much matter. Billy had a crook leg, but he didn’t give an inch . . . he even made a few runs and put his wingers away. But despite the victory and the huge celebrations that followed, it wasn’t much help to Norm Tipping.

We had chaired him off after the grand final, but Killer wouldn’t have a bar of him, and worse still Norm had a huge feud running with Frank Facer. Frank had taken over as club secretary during the year, and though he became a legendary administrator who was a large part of the St George success story, he was wild in those days, especially when he had had a drink. He and Tipping had come to blows more than once. Norm’s card was marked, and he was shattered when Killer was returned to the captain–coach role, which he held for the next five premiership years. It probably wasn’t very fair, but there was a ruthless edge to Facer and to Saints generally when it came to what would give us our best winning chance. Killer was the dominant personality in the club, and as events proved, he was right for the job.

Before we had kicked a ball in 1957, Kearney made a call that turned St George from a very good side into a great side. Harry Bath had proved a real champion in ten seasons in England, and when he came home that year he was looking for a bit of a wind-down to his career. He was 32, and both Balmain and Manly knocked him back on the basis that his best football was well and truly behind him. He was recommended to Saints, and Facer asked Killer what he thought. Kearney didn’t have to think. ‘Harry Bath,’ he said. ‘Grab him!’

Killer had seen Harry at first hand in England over four seasons and knew why many knowledgeable people there rated him the best forward in the world. He had all the creative skills that made English football as good as it was in those days, and Kearney well knew the impact he could have on St George. Facer took Kearney at his word and signed Bath there and then. Facer pulled in some great players in his time—Johnny Raper, Brian Clay, Kevin Ryan, Graeme Langlands and Dick Huddart among them—but as far as I am concerned Bath was the most important signing of them all.

Harry was up front about where he stood. It had been eleven years since he last played in Sydney and seventeen years since he first made first grade, and at 32 he knew he wasn’t going to be the physical force expected of most forwards in Sydney Rugby League. But he knew he could make a huge contribution to the way we played. Kearney had introduced many of the English ways to St George, but Killer would never put himself in Bath’s class when it came to tactical precision with the football. On top of that Harry was a great communicator, a natural coach in so many ways. He knew all the theories about what he was doing and why, and he had a great knack for imparting all that knowledge to the rest of us.

Much of what he did was very simple. He kept the ball in his hands, for a start, and moved his eyes around so that opponents could never be sure what he was going to do next. And he seemed to have a seventh sense about where people were going to be—both attackers and defenders. He would amble up to suck in defenders and he had the rest of us supporting on either side and in depth, so there were always options about where the ball would go. He found holes and he made holes, and before long we all knew that following Harry around the park would bring us lots of breaks.

Bobby Bugden thought it was Christmas. Bob was our halfback and a champion beach sprinter, and his pace off the mark was ideal as a support runner off Bath’s close work. Both Harry and Killer had changed the way the ball was handled. The standard pass, direct from hand to hand at a comfortable distance, gave way to a popped pass, a loopy ball that seemed to hang in the air and allowed support runners to line it up. Bath always seemed to pop that pass into a hole, and we all made merry.

Harry stayed for three seasons before he retired at 35 and started life as a top coach. We won all of those premierships and in his last year, when we went through the season undefeated and beat Manly in the grand final, we were simply untouchable. That 1959 side brought in Reg Gasnier and John Raper, and another young goer in John Riley, and Bath had been there long enough to have had his ways well and truly entrenched in the sort of football we all played.

I was a running second rower, but we all learned to look for ways of creating space and using supports. Reg Gasnier, nineteen and straight up from President’s Cup, was an instant sensation, and I could see great profit in linking with him whenever I could make a half break. Over the years we did a lot of that, with Gaz screaming for the ball as I angled my run and he came from the clouds at pace. Killer and Harry had a bit to do with all of that. They had learned lessons in England that complemented the discipline and the fitness and put us well ahead of the pack.

The 1959 grand final, in which Saints beat Manly 20–0, was the last game Harry Bath played in a long and distinguished career. It was somewhat ironic that he didn’t last the game, sent off in company with Rex Mossop nine minutes from the end after a fierce personal battle that seemed to go on forever. The pair had brought a strong rivalry with them from their English club football days, and Darcy Lawler had had enough by the time their team-mates had pulled them apart at the end of the 1959 grand final.

It has been said of Harry Bath that he was the best forward never to play for Australia, and I will endorse that. He played for NSW against England in 1946 only to be ruled out of the Test matches with injury, and he went off to England a season before the 1948 Kangaroos were picked. Even then, in his twilight years with us, I reckon he should have been chosen against England in 1958, and certainly for the Kangaroo tour of 1959. He was left out probably for political reasons, because he had played in England for so long. It was a consolation, I suppose, that within a couple of years of retiring he was appointed Australian coach.

My opinion of Harry Bath as a footballer is pretty straightforward. He was the best forward I ever played with. I know that is a big statement when you consider that I played a lot of years with Johnny Raper and some other pretty outstanding players. Raper had strengths that nobody else had, and he has always deserved his ranking as an Immortal. But for sheer influence on the game . . . for the impact he had on all the people around him and for the knowledge that kept pouring out of him, Harry Bath was a marvel.

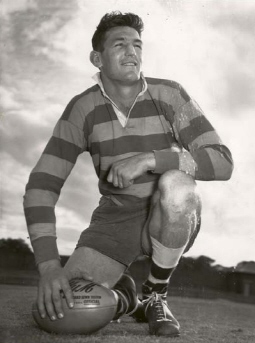

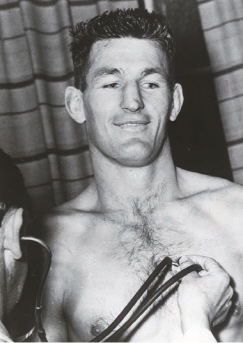

Norm Provan, 1958 vintage, about to demolish a Balmain attack. Courtesy of Rugby League Week

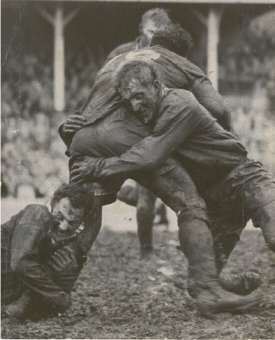

Norm Provan is all aggression in a club match against North Sydney.

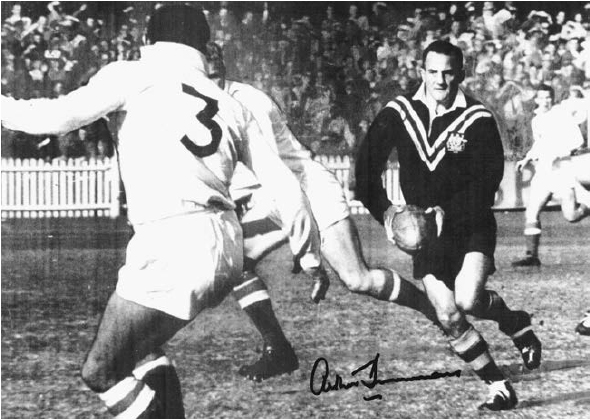

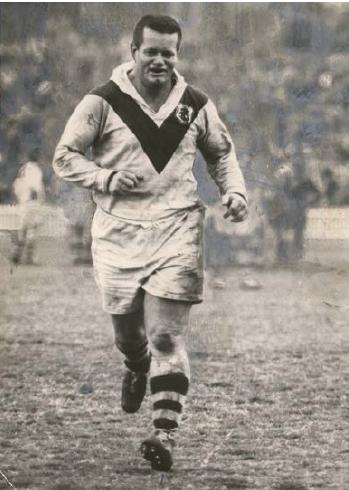

Arthur Summons on the move against England in 1962. He led them to victory in the final Test. Courtesy of Arthur Summons

The Wests grand final team of 1963. So near and yet so far. Courtesy of Arthur Summons

Back row: John Hayes, Jack Gibson, Kel O’Shea, Dennis Meaney, Noel Kelly, John Mowbray. Front row: Kevin Smyth, Peter Dimond, Gil McDougall, Arthur Summons (captain), Bob McGuiness, Don Malone, Don Parish. Ball boy: John Beaver

Darcy Lawler takes the field ahead of Kel O’Shea and Norm Provan at the start of an epic grand final between Saints and Wests at Sydney Cricket Ground.

It was an age when mud was a part of every season, especially at the SCG. Arthur Summons and John Raper combine to bring down New Zealand hooker Jack Butterfield in a Sydney Test. Courtesy of Rugby League Week

John O’Gready and his trusty camera—an artist who gave Rugby League an enduring symbol.

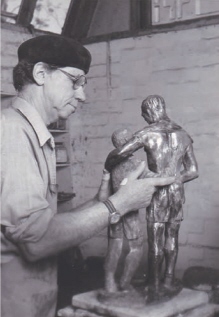

Sculptor Alan Ingham at work in his Sydney studio as the original Winfield Cup takes shape. Photo: David George

The moulds are crafted as the work is painstakingly progressed. Photo: David George

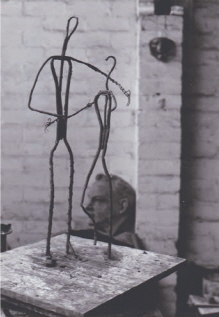

Great icons begin with small steps. The stick figures were the sculptor’s early guide as work began. Photo: David George

The original Winfield Cup on show, with satisfaction all round from photographer John O’Gready (left), sculptor Alan Ingham, Winfield executive Maurie Brien and Arthur Summons. Courtesy of Arthur Summons

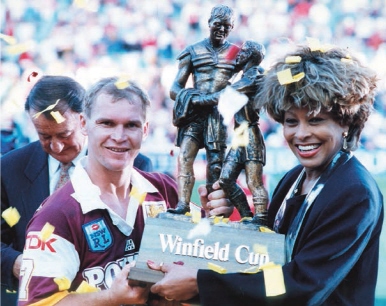

Tina Turner presents the Winfield Cup to Brisbane captain Alfie Langer after the 1993 grand final win over St George. Photo: Newspix

Melbourne Storm champions Cameron Smith and Greg Inglis with NRL CEO David Gallop, Norm Provan and Arthur Summons at the 2008 launch of Rugby League’s centenary season at Birchgrove Oval in Sydney. Photo: Newspix

Norm Provan and Arthur Summons replicate the image of another time for a centenary season TV commercial at Leichhardt Oval in 2008. Photo: Newspix

Already a tough guy . . . Norm Provan shows off his physique as an athletic three-year-old, circa 1934. Courtesy of Norm Provan

The Provan brothers (from left) Ian, Donald, Norm, Rupert and Peter. Courtesy of Norm Provan

Norm Provan at the start of it all—a young man on the way to greatness. Courtesy of Rugby League Week

Norm Provan is the knockabout boss at a Norm Provan Discounts Christmas party in the 1970s. Courtesy of Norm Provan

Arthur Summons at four years old. The nose is still straight, and the world is his oyster. Courtesy of Arthur Summons

Arthur Summons (holding football) with his Homebush High School First XV in 1952. Courtesy of Arthur Summons

The Gordon Rugby Union premiership team of 1956 boasted eight Wallabies. Arthur Summons (seated far right front row) was one of them. Courtesy of Arthur Summons

In December 1956, 21-year-old Arthur Summons tied the knot with his wife of 56 years, Pam Laidlaw. Courtesy of Arthur Summons

Ken ‘Killer’ Kearney was the man who set St George on the road to glory . . . a hard and uncompromising hooker who had to fight for his success at every scrum.

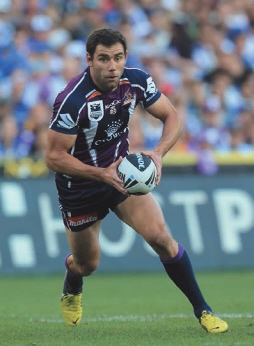

Melbourne’s Cameron Smith is a champion of the modern game, a classic example of how the hooker’s role has evolved into a collection of silken skills in the fashion of the modern playmaker. Photo: Newspix

Norm Provan gets the medical once-over. Many teams of the era were lucky to have much medical assistance at all. Courtesy of Rugby League Week

Captain–coach was a role in which Norm Provan thrived. Here he lays down the law to his team of champions at training.

NSW Rugby League secretary Harold Matthews wishes Kangaroo captain Arthur Summons good luck as the team departs Mascot at the start of their 1963–64 tour. Courtesy of Rugby League Week

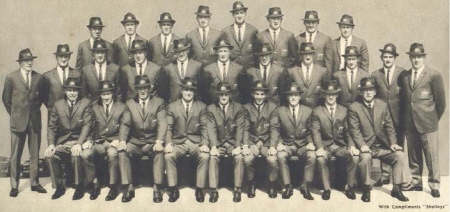

The 1963–64 Kangaroos, who became the first team to bring back the Ashes from England, and who remain one of the greatest teams of all time. Courtesy of Arthur Summons Back row: John Gleeson, Barry Rushworth, Jim Lisle, Graeme Langlands, Paul Quinn, Graham Wilson, Peter Dimond, Les Johns. Middle row: Frank Stanton, Johnny Raper, Michael Cleary, Dick Thornett, Peter Gallagher, Kevin Ryan, Ken Thornett, Brian Hambly, Kevin Smyth, Reg Gasnier, Noel Kelly. Front row: Arthur Sparks (manager), Ken Day, John Cleary, Ian Walsh (vice-captain), Arthur Summons (captain–coach), Ken Irvine, Barry Muir, Earl Harrison, Jack Lynch (manager).

Arthur and Pam Summons with Norm Provan and Dave Emanuel, another champion second-rower of Arthur’s Rugby days and a lifelong friend. Courtesy of Arthur Summons

Norm Provan, Arthur Summons and the original trophy that brought them enduring fame. Courtesy of Arthur Summons

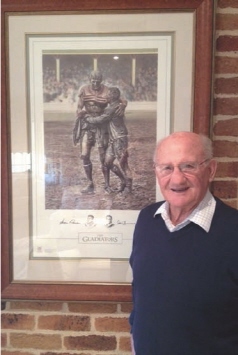

Norm Provan poses with the painting that hangs in his living room—a masterful representation of John O’Gready’s original photograph. Courtesy of Norm Provan

Arthur Summons and Brian Clinton’s painting, a dominant feature of his Wagga lounge room. Courtesy of Arthur Summons