Gods, Goddesses,

and Pantheons

All the gods are one god; and all the goddesses are one goddess, and there is one initiator.

—Dion Fortune, Aspects of Occultism19

spirit (source of all things)

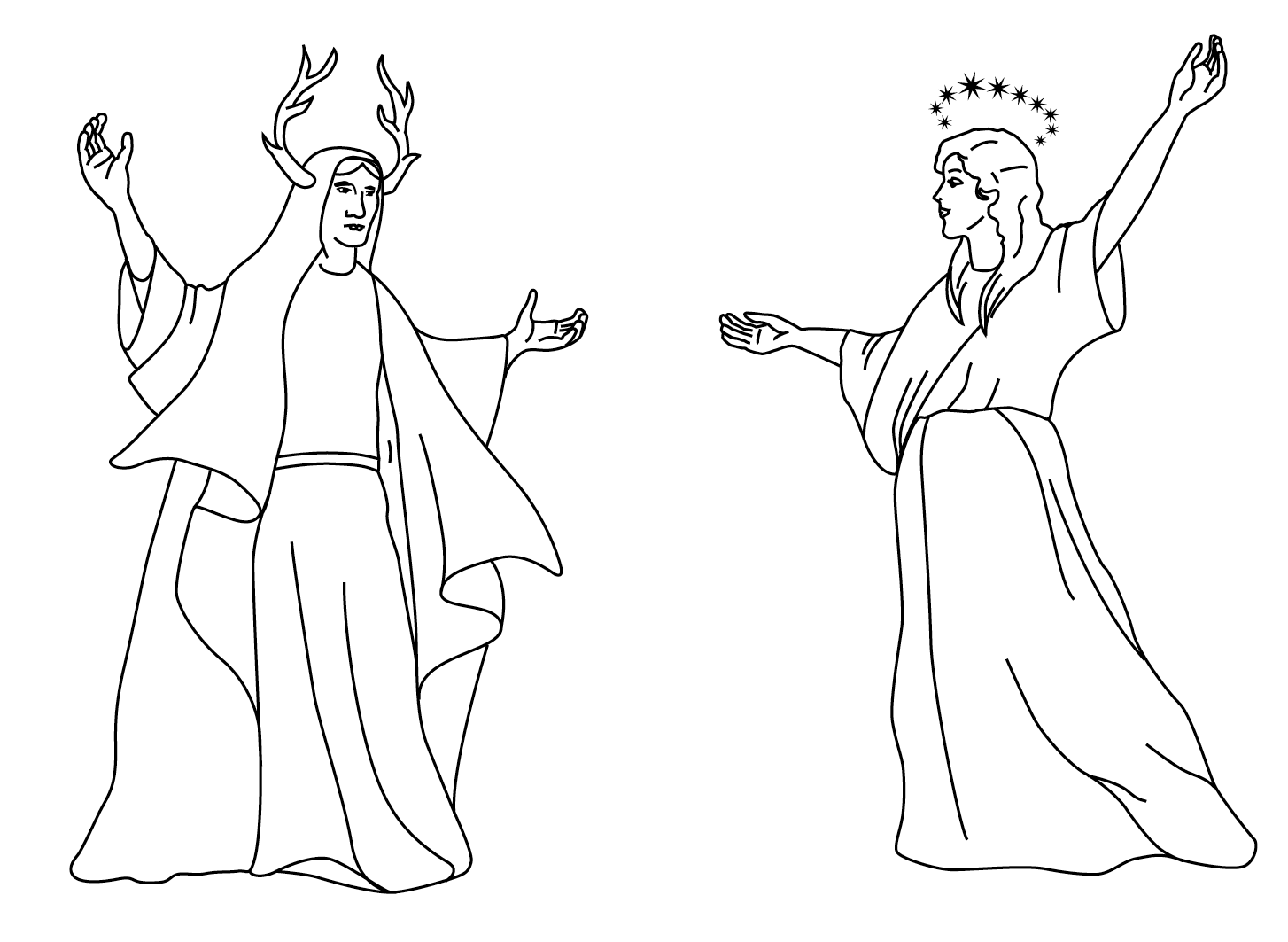

The God; The Goddess

The Lord; The Lady

Father, Son, Sage; Maiden, Mother, Crone

Male Deities; Female Deities

The concept of what God is to every Wiccan becomes a deep, philosophical, and precious subject. If you are into science and quantum physics, then you probably believe that God is the perfection of the universe, and to give it a name and a personality, to build myth and dogma around such a concept, may seem pretty silly. Indeed, all the blood, death, and horrible things done in the name of a god (any god, mind you) becomes more than ludicrous. But we are humans, after all, and we need that personal touch—which is how all great religions are born. The religion of Witchcraft allows people to believe what they want in respect to “what runs the universe.” It is this freedom of faith that makes the religion so powerful, and although you may find us arguing—about which quarter comes first, how one properly casts a circle, historical information (everyone argues about that!), or whose lineage is valid (or not)—you’ll not find us quibbling over the validity of one’s personal concept of god/dess (unless, of course, you try to draw dogma from another religion into it—dogma, in this sense, means established doctrine, code, or opinion concerning faith formally dictated by a religious body, like the Christian church). Most Wiccans believe that there is a single source of positive energy or force that runs the universe. Because it is hard to connect in times of trial with a “source,” we’ve divided it into the Lord and the Lady—male and female. Sometimes They are called the Master and Mistress of the Universe. That’s why, when we say “and together They are one,” we see the combined force of the Lord and the Lady as the totality of all that is positive and good. When you reach the study of alchemy in this book (see Part 4), you will notice that we find our current concept of the world-soul (that is sometimes split between the female divine of the starry heavens and the god of earth who protects and cares for us all—and together they are united) in the Hermetic doctrine. From the Greeks comes the idea of just the opposite—that the sky becomes the divine masculine and the earth is the divine feminine. Again, these two heavenly powers are united as one.

Some historians believe that it was Charles Kingsley in his novel Hypatia (1852) that gave rise to the idea that the Greek philosophy recognized the existence of the one true deity, of whom Pagan goddesses and gods were merely aspects;20 Ronald Hutton, in private correspondence dated 9 August 2002, agrees that “Kingsley was quite correct, for virtually all Greek philosophers taught this, especially Platonists, Stoics, and Neoplatonists”—(which have affected modern Craft practices more than you know—it is interesting that we put more stock in this triumvirate than those who lived at the time)—“The problem for historians is that there is no sign that the vast majority of ancient Greeks and Romans paid attention to what the philosophers said, and desisted from believing in many deities.” In modern Craft lingo, you will hear about the theory of aspecting, which is where the Witch becomes either divinely feminine or divinely masculine by drawing deity into him- or herself in ritual—known in some alternative Christian circles as the concept of “I am.” Aspecting, in this case, is divine possession by deity—and no, last I checked, no one rolls on the ground or froths at the mouth in a Wiccan circle. It just ain’t done.

For some Crafters, the idea of all-deities-as-one provides the power and unity they psychologically need to connect them to all of nature. It is certainly true that today’s Wiccans and Pagans, in their effort to reconstruct and revitalize ancient ideas, have been influenced by those who have gone before, especially in the body of work presented by the Romantic movement in the late eighteenth century in the form of literature and poetry. It is also true that the overwhelming majority of ancient Pagans genuinely believed that the different goddesses and gods were separate personalities, and that in only one ancient text appearing at the end of the Pagan period did the author declare that his favorite goddess was the embodiment of all other goddesses.21 Although you may think this incredibly confusing, modern Wicca has managed to open its arms (and keep them open) in regard to one’s personal deity choice and the hierarchy or pecking order that they represent.

In researching various coven dynamics in England, Ronald Hutton wrote the following:

Among Witches I have found people who think of their goddess and god as archetypes of the natural world or of human experience, others who regard them as projections of human need and emotion which have taken on a life of their own, others who see them merely as convenient symbols, and yet others who have a belief in them as independent beings with whom relationships can be made. . . . More remarkable, and significant, I have encountered all those viewpoints within a single coven, co-existing in perfect harmony because the members never felt the need to . . . debate them.22

He’s absolutely right.

Another interesting ancient deity concept often favored by Witches is the trinity. The idea that “three make one” isn’t a foreign construct in the major religions of today; in Christianity, we see Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. Here, the Father and Son are male, and the Holy Ghost is female (although this information isn’t often discussed). In the Jewish Kabbalah, there are several manifestations of three-to-make-one, including the daughter, bride, and mother of Malkhut (the feminine presence of God, sometimes referred to as the Shekinah) to combine the energies of the Tree of Life in various sequences of three that can be used for meditation and raising one’s spiritual purpose.

Most of today’s Crafters agree that within every god and every goddess is the energy of the “single source”—and what that source may be is part of the Great Mystery. Many Wiccans use pantheons (family trees of gods and goddess linked by cultural belief) as representations of the single source—with personality. That means that if you plan to use a particular pantheon, or choose a specific god or goddess to work with, you must research his or her entire mythos, or story.

Many times you will discover that the gods and goddesses of a particular pantheon pick you, you don’t pick them. Each has its own energy pattern, and you will be drawn to those that best match your cosmic construction. When this occurs—through meditation, an event, or other situation—the Crafter often relates to others that this particular god or goddess is his or her patron deity, meaning that, above all others, this deity is often the main focus of the Crafter’s work. This is not to say that they don’t use other deity forms in ritual and worship, or that he or she might balance the patron with another equally powerful deity, which often occurs. For example, if you work with a dark goddess as your patron deity, at some point you will be required to work with her balance (in male form and in light) and vice versa.

Traditional Wiccan groups normally have a single, chosen pantheon used by all the members for sabbats, esbats, group workings, initiations, circlecasting, and quarter calls. Everything matches. This doesn’t mean that these Witches don’t work with other deities and pantheons on their own, outside of the group. Many do. The idea of everyone following the same pantheon “tune” is, above all, a question of focus. If three people are thinking of a Celtic goddess, and four are calling Isis, and another person throws an Aztec war god in there, you’ve got quite a muddy mix. Experienced Witches have also learned that, just as all should be focusing on the same deity or set of deities, all deity representations should be from the same pantheon for any single ritual. Here, you are also working with cultural energy patterns. If you try to mix them (e.g., Celtic at one quarter, Roman at another, American Indian at the third, and Norse at the fourth, then invoke a Chinese goddess for aid in the magickal working itself), the cultural patterns won’t blend well, and it is highly possible that one (or all of them) won’t show up or, worse, will throw a tantrum. (When I said deity “with personality,” I wasn’t kidding.)

When first entering the religion of the Craft many students work with the concept of the Lord and the Lady before tackling the research required in using pantheons and their associated deities. Others may call this duo divinity the Master and Mistress of the Universe. Focusing on only two basic energies isn’t a bad idea, and gives you time to work with the three-in-one concept (male, female, and unity of the two) in a new way. When you are ready to examine pantheons, many groups want you to write five- to ten-page papers on each deity in the group’s selected pantheon before you use them, hoping that your efforts in research will bring you a wider understanding of the deity energy. Where do you find this information? At the library, in books on history, religion, and archeology. There’s no other way around it. Every deity has its own personality, which will affect your magickal working. It’s up to you to choose which personality and legend serves you best. In Witchcraft, your history in relationship to the gods is not laid out for you in one nifty, neat-o book. It is expected that you will go digging under your own steam, allowing Spirit to guide you to the information that will serve you best at a particular time in your life. In time you will probably collect statues and pictures of your favorite deities. When a Witch says, “I am a priestess (or priest) of . . . ” and names a particular deity, it is often because he or she has had a life-altering experience (called an epiphany) that involves that deity energy, and has chosen that deity as his or her patron. Magickal groups also have patron deities, wherein one single deity “rules” the clan or group. In the Black Forest, for example, the patron deity is the Morrigan. The concept of a deity as patron stems from pre-Christian Roman times and is very much a product of that culture’s hierarchy.

What if you don’t want to do all that work and research? Stick with the Lord and the Lady, or Master and Mistress of the Universe. Eventually you will read something about a particular god or goddess that interests you, and off you’ll go on a quest to find out as much as you can. Over time, you’ll amass quite a library of your own and have lots of notes from research you’ve done. You can put this information into your personal Book of Shadows until it gets too thick (it will happen), and then you can break the information out into its own book.

In the Craft, there are no middlemen to God. It’s you and the divine. In a coven environment, a high priest and a high priestess are facilitators of the group government. Yes, they do aspect the divine. And yes, they do try very hard (usually) to be a proper conduit for the need at hand, but they cannot substitute themselves in your life as your god or goddess. They aren’t any better than the other members of their group, and they don’t get favors from deity because they hold that rank (which, by the way, is a heck of a lot of work). Every Witch, regardless of whether they belong to a group or not, is a Witch alone. In the eyes of divinity, each stands on his or her own two feet in ritual, magick, and learning. The only difference between a high priestess and a new Witch should be knowledge and maturity, and even then there are always exceptions to the rule.

Up until this point, you may have noticed that I haven’t talked about Satan at all. That’s because Witches don’t believe in him. He belongs in the Christian pantheon, and he can stay there (which is why most Witches don’t use the Christian pantheon). Witches believe that to give evil a name is to create that evil. Why bother to do that? Humans manage to manufacture enough evil in the world on their own, without slapping it on the shoulders of a mythical beastie. Most Witches believe that there wouldn’t be any evil in the world if humans didn’t keep creating it by their own dastardly deeds, whether they are done in the name of a religion or for one’s own personal gain.

If we use other pantheons, why don’t most of us work with the Christian one? There’s more than one answer to this question, and I think it partially depends on who you are talking to, their personality, their educational background (as far as history and magick are concerned), and the experiences they have had in other religious structures. The pantheons, as most of us work with them today, do not single out evil by giving it a name and personality. Each god and goddess has their own personality, and in that personality they have a dark side and a light side, order and chaos, animal and spiritual—just like people. That’s why we study their legends. How you use this energy is extremely important. In the Christian pantheon, the dark side is given individual power through the idea of Satan and his many demons (thanks to early Christian clerics playing with the Arabic Zoroastrian system, which predates Christianity). Some magickal people feel that by separating this darkness and allowing it to stand on its own, the Christian religion weakened their own pantheon, leaving the door wide open for a person to rationalize away his or her own responsibility to themselves and to the world. For some people it is easier to look to a new system (or pantheon), rather than bear the weight of negative dogma.

When one of my daughters was interviewed by a reporter writing for a major parental webpage last year, she was asked, “Do you worship Satan?” Her response was, “I wouldn’t be that stupid.” Many Wiccans today find this question not only irritating, but insulting. My daughter continued by saying, “It is the major religions of this world that play with Satan, not us. You are trying to equate my religion to yours, and that’s not fair.” Angered, the reporter never printed the story.

For others, it is the history of the Christian church that makes it so unappealing. One Wiccan teen, standing at the threshold of a Protestant church on Girl Scout Sunday, said, “I can’t go in there.” When her mother asked her why not, she replied, “Because if the people who go to this church every Sunday knew the amount of blood spilled and horrors done in the name of Christianity over the last 2,000 years so that this building could stand here, I would like to think that they wouldn’t go in either. I can’t go in a place that tells me they are preaching the truth, when they are lying through their teeth about their own history.” She, along with five other girls, spent the hour during the service in the church garden.

Another reason why many don’t use the Christian pantheon is the absence of male/female balance. Christianity is a patriarchal religion, or male-dominated faith, and many women and men find this idea equally offensive. Although some Wiccans learn to “plug in” female divinity somewhere in the Christian pantheon, relying on old information from Gnostic texts and other areas, the system itself, and many of its current practitioners, continue to view the presence of women as something that must be tolerated, not celebrated, and certainly within the system as it now stands the female principle will never be elevated to equal divine status. The Witch who also practices Christianity, then, will at some time have to come to a personal truce on the subject and look beyond the confines of the Christian dogma that grips its adherents so tightly. Can he or she work with a pantheon that says, depending upon the sect, women aren’t as good as men, or that relies on dogma rather than truth? You will find even fewer Wiccans working with the Islamic pantheon because of the cultural (not necessarily religious) attitude of degradation toward women in certain areas of the world today.

Does this mean that Christianity is a bad religion, and that you can’t work magick or advance spiritually within its ranks? Remember, I was giving you the reasons why many Wiccans don’t work with the pantheon, which doesn’t mean that you can’t work magick, be spiritual, or become what you desire in the confines of that belief system. Ceremonial magicians, who use Christianity, Judaism, and magick together, seem to get along quite well. Some of these magickal people also use Pagan pantheons, particularly the Egyptian one. Just as in other practices, there are many different groups under the ceremonial umbrella. There are also a few European Druid groups that have not let go of the Christian dogma—it is simply too ingrained in their cultural practices. If you want to work this way, take your time to choose which is right for you. Just remember that you are working with your own construct, and in view of some (not all) Wiccan circles, you will not be considered either a Witch or a Wiccan. To pique your historical interest, there was another time in history where people wanted to practice the magick of Witches but didn’t want to use the religion of the Craft or play with the expense and literacy required of the ceremonial crew. These people were known in towns and villages as “cunning folk,” and much of their magickal material included bits and pieces of Pagan magick melded into the Christian mythos. Unfortunately, their desire to take and not to respect led to the deaths of thousands of people and the degradation of the name of Witchcraft, wherein lies another reason that many Witches today find the idea of a Christian Witch not only an oxymoron, but an insult as well.

Where ceremonialists may borrow from other pantheons, so, too, have Wiccans borrowed from the ceremonialists, as you can see from many of the historical roots of various magickal practices discussed in this book. The title Ceremonial Witch does not mean that the Witch is using the Christian pantheon, rather that the Witch likes lots of bells and whistles in ritual, follows a structured format (rather than a spontaneous one), and often tends toward more erudite studies. For some Witches, then, religious practice is ceremonial minus the Christian and Judaic influence, specifically Alexandrian and Gardnerian (to name two). For others, Wicca is a not so much a trip into erudition and devout structure as it is a free-flowing journey to the divine through nature’s way—a more shamanistic approach to finding God. Still other groups mix the two (shamanistic and ceremonial) for different rituals or for group government purposes. As mentioned, ceremonial Wicca does not use the Christian or Judaic dogma, but may rely heavily on Arabic or Judaic mysticism mixed with a Pagan pantheon.

Finally, some Wiccans like to use pantheons because the religious leaders and rule makers of those cultures are dead. They can’t tell you what to do, or that you are doing something “the wrong way,” or that you are a bad person because you don’t think like the rest of the cultural pack. The pantheons of the Greeks, Norse, Egyptians, Celts, and Romans (the ever-present favorites) cannot exclude us just because somebody said so. This doesn’t mean, however, we won’t get smacked if we use the energies of the pantheon in a less than honorable way—although the culture is dead, the patterns of energy are not.

Buzzwords

You’ll hear these on Internet discussion boards in relation to deity and religion.

Animism: The belief that the forces of nature are inhabited by spirits.

Canon: Rule, law, model, or standard; often used by the early Christian church to squash people’s rights, especially in dictating what they could and could not believe.

Culture: The sum total of those things (including traditions, techniques, material goods, and symbol systems) that people have invented, developed, and transmitted to each other.

Karma: A Sanskrit word that means “deed”—the law says that one’s deeds determine one’s future life.

Monotheism: The belief in only one god.

Pantheism: The belief that a divine spirit encompasses all things in the universe.

Polytheism: The belief in many gods.

Prehistory: The study of history before

written records.

Theocratic Monarch: A human being who rules as the representative of a god or gods, and believes that he or she is the divine made flesh (and therefore better than the common rabble).

Pantheons Most Used

in Modern Witchcraft

Listed on the following pages are five of the most-used pantheons in the religion of Witchcraft. This collection is only meant to get you started, and does not represent the thorough research you should do before working with any deity. Pantheons are tricky. For example, the Celtic pantheon, when you get deeper into it, has a three-tiered classification—the first, the children or subjects of Danu, were the Irish pantheon, a divine society of beings associated with each other and dwelling in a parallel world with its own politics, customs, and functions,23 yet they also had children (sometimes the heroes and heroines of epic proportions and who represent the second tier), who encountered not only humans, but nature spirits (the third tier). The Norse tradition is much the same, and the Grecian and Roman pantheons also have lesser deities that are half-human and half-god. With the Egyptian pantheon, all kings or pharaohs were considered god in human form, and therefore they were to be worshipped as well (usually only as long as they were in power, though a few turned into gods later on, much like the Voodoo Lwa and the concept that Marie Laveau—a deceased New Orleans Voodoo priestess who is credited with major contributions to her faith and to her people—can be considered a goddess/Lwa in her own right because she earned it). Also floating through all these pantheons are the errors of history in mistakes never corrected or information that was lost.

Greek Pantheon

Zeus: Divine god

Hera: Wife of Zeus, Mother Goddess

Apollo: God of prophecy, archery, and music

Aphrodite: Goddess of love

Ariadne: Goddess of the labyrinth

Aries: God of action and war

Artemis: Goddess of the hunt and protection

Athena: Goddess of war and wisdom

Calliope: Muse of epic poetry (female)

Clio: Muse of history (female)

Demeter: Earth goddess

Dionysus: God of wine and ecstasy

Eileithia: Goddess of childbirth

Erato: Muse of love poetry (female)

Eros: God of love

Euterpe: Muse of music (female)

Gaia: Primal earth goddess

Hecate: Goddess of Witchcraft, ghosts, and the dead

Hades: God of the underworld

Helios: God of the sun

Hephaistos: God of sun, fire, and forge

Hermes: Messenger to the gods (male)

Hestia: Goddess of hearth and home

Melpomene: Muse of tragedy (female)

Metis: Wisdom

Moerae: Three goddesses of fate—Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos

Mnemosyne: Goddess of memory, mother of Muses

Nike: Goddess of victory

Pan: God of the forests

Persephone: Queen of the underworld

Phoebe: Goddess of the moon

Polyhymnia: Muse of singing (female)

Poseidon: God of the sea

Psyche: Goddess of the soul

Terpsichore: Muse of dance (female)

Tethys: Goddess of the sea

Thalia: Muse of comedy (female)

Theia: Goddess of light

Urania: Muse of astronomy (female)

Roman Pantheon

Jupiter: Great God; storms, thunder, and lightening

Juno: Queen of Gods; women, marriage, childbirth, household prosperity

Apollo: God of the sun, music, poetry, fine arts, prophecy, eloquence, and medicine

Bacchus: God of liquid spirits, fruits, and parties

Ceres: Goddess of harvest, agriculture, fertility, and fruitfulness

Cupid: God of love and passion

Diana: Goddess of the moon, hunting, children, and Witches

Fanus: God of the woodlands

Fates: Three goddesses of destiny; daughters of the night

Flora: Goddess of nature

Furies: Goddesses of vengeance

Janus: Two-faced god of beginnings

Mars: God of war and action

Mercury: Messenger of the gods, trade and commerce, travelers

Minerva: Goddess of wisdom, practical arts, and war

Neptune: God of the sea, earthquakes, and horses

Pluto: God of the underworld

Saturn: God of harvest and golden ages in history

Venus: Goddess of love

Vesta: Goddess of the hearth, home, and community

Vulcan: God of fire, craftspeople, metalworkers, and artisans

Celtic Pantheon

Dagda: Father God (the good god)

Danu (Anu)/Don: Mother Goddess

Abarta: Warrior energy (Irish)

Aine: Goddess of love and fertility (Irish)

Amaethon: God of agriculture (Welsh)

Aonghus: God of love (Irish)

Badb: Goddess of battle—one of the three faces of the Morrigan (Irish)

Belenus: Sun god (Welsh/Irish)

Bran: God of sea voyages

Bran the Blessed: God of the underworld (British)

Brigantia: Goddess of the water, war, healing, and prosperity

Brigid: Goddess of healing, fertility, poetry, and the forge (Irish)

Ceridwen: Goddess of fertility (Welsh)

Dian Cecht: God of healing (Irish)

Dylan: God of the sea (Welsh)

Epona: Goddess of sweet water, fertility, and horses (Welsh)

Lir: God of the sea (Irish)

Lugh: God of the sun (Irish)

Macha: Goddess of war—one of the three faces of the Morrigan

Morrigan: Goddess of war; original goddess of the earth and agriculture

Nemain: Goddess of war (Irish)

Nodens: God of healing (British)

Nuada: God of valor

Ogma: God of eloquence (British)

Rhiannon: Goddess of suffering and patience (Welsh)

Scathach: Goddess of martial arts and warrior-princess of the Land of Shadows

Taliesin: Prophet and bard (Welsh)

Tuatha de Danann: People of the Goddess Dana

Norse/Germanic Pantheon

Aegir: God of the sea (Germanic)

The Aesir: The younger branch of the family of the gods (Germanic)

Baba Yaga: Avenger of women (Slavic)

Buri: Ancestor of the gods (Germanic)

Dazhbog: God of the sun (Slavic)

Forseti: God of justice (Germanic)

Freyja: Goddess of fertility (Germanic)

Frigg: Queen of the gods

Gefion: Goddess of fertility (Germanic)

Hel: Goddess of the underworld and the dead (Germanic)

Huginn and Muninn: Ravens—Thought and Memory—belonging to Odin; messengers (Germanic)

Idun: Goddess of youth and apples (Germanic)

Jumala: Creator god of Finnish mythology

Kied Kie Jubmel: Lord of the herds, stone god (Lapp)

Leib-Olmai: Lord of the bears (Lapp)

Loki: God of fire (Germanic)

Luonnotar: Creatrix goddess (Finnish)

Madder-Akka and Madder-Atcha: Divine couple who created humankind (Lapps)

Mati Syra Zemlya: Moist Earth Mother (Slavic)

Menu: Moon god (Baltic)

Nerthus: Mother Goddess (Germanic)

Njord: God of the sea (Germanic)

Norns: Goddesses of Fate—Urd (Past), Verdandi (Present), Skuld (Future) (Germanic)

Odin: Father of the gods; gifted in eloquence

Perunu: God of thunder (Slavic)

Potrimpo: God of fertility (Slavic)

Rig: Watchman of the gods (Germanic)

Saule: Goddess of the sun (Slavic)

Skadi: Goddess of vengeance and the hunt (Germanic)

Svarazic: God of fire (Slavic)

Tapio: God of the forest (Finnish)

Thor: God of thunder (Germanic)

Tuoni: God of the dead (Finnish)

Tyr (Tiwaz): God of the sky and bravery (Germanic)

Valkyries: Female battle and shield maidens who take brave warriors to Valhalla, the idyllic abode of Odin’s ghostly army (Germanic)

The Vanir: The older of the two branches of the Germanic family of gods

Vidar: God of justice (Germanic)

Egyptian Pantheon

No overall male and female figures that equate to the Lord and Lady are given, as the Egyptian civilization was the longest in human history. Gods and goddesses changed or gained or lost prominence over the centuries.

Amon: First worshipped as a fertility god; rose to prominence for a time as the most important god of Egypt

Anath: Mistress of heaven, protector of the king; known for her ferocity

Anubis: God of the dead and protection; Input is his female counterpart

Anukis: Goddess of water

Apis: The Black Bull, symbol of fertility and the undying soul

Aten: Sun god who turned into a monotheistic entity, then lost his footing among the other gods and goddesses

Bastet: Goddess of cats, fertility, music, the moon, and protection from evil (associated with Sekhmet)

Bes: God of good fortune and protection of pregnant women; Beset is the female side of Bes

Geb: God of the Earth

Hathor: Goddess of business, beauty, joy, love, harmony, children, and the all-seeing “Eye of Ra”

Horus: God of the sky, divine child

Hauhet: Goddess of boundless infinity; Hu is her male counterpart

Hekat: Goddess of midwifery and childbirth, associated with water

Isis: Goddess of All; Divine Mother; partnered with God Osiris

Ius-a’as: Goddess of creation

Ma’at: Goddess of truth

Mehet-Weret: Goddess of sky and floods

Merit: Goddess of music

Min: God of roads, fertility, and agriculture; protector of travelers

Neith: Goddess of destiny, war, and the mother of Ra; protector of the dead; bisexual

Nekhbet: Primal Mother Goddess; divine nurse

Nephthys: Goddess of secrets, initiation, and the dead

Nut: Goddess of the sky

Osiris: God of vegetation and the dead; rules with Isis

Ptah: God of learning, architecture, and building

Ra: God of the sun

Renenet: Goddess of prosperity and the home

Sekhmet: Goddess of protection

Selket: Goddess of scorpions; protector of the dead, travelers, and weather

Seshat: Goddess of writing and patron of libraries

Seth: God of storms and chaos; although unfriendly and cruel, he was respected

Shu: Goddess of moisture

Sobek: Crocodile God of lakes and protection

Taweret: Hippo goddess of childbirth

Tefnut: God of air

Thoth: God of knowledge, wisdom, and the moon

Wadjet: Serpent goddess of protection, children, and the land

Wenut: The “swift one”—moves things quickly; hare or serpent

Wosret: The powerful woman

Where Did Our Goddess

Come From?

The Great Mother Goddess took shape in the mind of man during the Paleolithic Age (5 million to 10,000 b.c.e.). Perceived as the life-giver and identified with the mysterious powers of procreation, her exalted form carried importance in the prehistoric community, which is confirmed by the great numbers of female statuettes uncovered by archeologists throughout the world.24 The Neolithic or New Stone Culture lasted from 8000 to 4000 b.c.e. Here, too, we find real indications that the Mother Goddess moved with the growth of the human mind into this era. The overwhelming evidence of female statuettes found in Neolithic graves continues to suggest that the belief in the Earth Mother may have become even more important in the transition from food gathering to food production, when fertility and agricultural abundance were vital to the life of the community.25

When we look at creation stories (see page 18), we discover that in many ancient cultures, references to the Goddess come first. She is the darkness from which light came, the void from which all things were born; She is the beginning. When we examine the Charge of the Goddess (see page 5), we see this affirmed in our own Wiccan religion—“from me all things are born, and to me all things shall return.” Yet our Goddess, as we know Her, can take a great deal of credit for Her entrance into our culture through the works of three distinct individuals: Jane Ellen Harrison, Sir Edmund Chambers, and Sir Arthur Evans. Chambers, a civil servant and a scholar of the medieval stage of human development, declared in 1903 that prehistoric Europe worshipped a Great Earth Mother in two aspects, creatrix and destroyer, who was known by many names.26 Ronald Hutton notes:

Chambers was not the main influence on the entrance of the Goddess into modern culture. That honor should go to his immediate contemporary, Jane Ellen Harrison of Cambridge University, who promoted the concept where it most mattered, among classicists and ancient historians. What Chambers did was introduce it subsequently to scholars of English literature, while it was prominently promoted among archeologists by Sir Arthur Evans, the person who made the discoveries in Crete.27

It was Evans’ discoveries in 1901 in Crete that led to a plethora of work on the subject by scholars of his time. Through this time period, the Goddess rose from the archeological dead. In 1948, a fellow by the name of Robert Graves fired the public with his rendition of The White Goddess.

Using his full tremendous talents as a poet, his excellent knowledge of the Greek and Roman classics, and a rather slighter acquaintance with early Irish Welsh literature, Graves developed the icon of the universal ancient European deity beyond the point at which it had been left in the 1900s. He took the imagery of . . . the three aspects and related them to the waxing, full, and waning moons to represent the One Goddess most potently as a bringer of life and death in her forms as Maiden, Mother, and Crone. He divided her son and consort into two opposed aspects of his own, as God of the Waxing and of the Waning Year, fated to be rivals and combatants for her love. An especially important function of the Goddess, for Graves, was that she gave inspiration. . . .28

Whether or not She had been complete before is not an issue; what is important is that She emerged fully functional in the Year of the Goddess, 1948, and She was ready for a new twist on religion—modern Witchcraft. She was indeed a countercultural deity who was to place a delicate but firm foot on the neck of patriarchy, Christianity, and the industrial world.

If this is so, how did She get buried in the first place? The birth of unified civilization, as we understand it today, seems to have put the first major dent in the idea of the supremacy of the Goddess, digging a grave from which most believed She would never rise. As Neolithic villages gave way to city-states—as mankind strove to conquer, tame, and control the environment as well as his own kind—so the strength and power of the Goddess (and Her human female counterparts) fell victim to the violence constructed by a male-dominated society. A good look at Afghan-istan today (I write this as the conflict has been thrown full force into the media eye of the world) shows us how, as women become degraded and abused, so their divine archetype is slowly strangled. The Goddess of the ancients, however, didn’t go easily into that dark night of modern, structured religion. For thousands of years She continued to speak from many faces—Astarte in Babylon and Sumeria; Isis (and others) from Egypt; Danu of the Celts; and Mary, Sophia, and Brigid of medieval Europe, to name a few. It is, unfortunately, our modern culture that stares at ancient history like a rabbit caught in the headlights of a truck.

Goddess? What goddess?

Of course there is a great deal more to learn about the history of the Goddess and how She has floated in and out of our cultural and social models throughout history. And where there is history, there will be controversy on “the facts.” Case in point: Mary Magdalene was not a prostitute, and indeed many of the stories about Mary Magdalene are nothing more than a collection of many Marys (as Mary was the predominant female name in Christ’s time) jumbled into one mythos. Indeed, according to historians today, Mary Magdalene was considered the most spiritually aggressive of the disciples, and it was her dollars that funded the rest of the male crew while they romped around the Holy Land spreading their message of hope for the future. Ain’t it always the way. (Just kidding.) I still want to know how she turned that white egg to red (but I digress) . . .29

Regardless of such stories, we know that the supremacy of the Goddess even existed in early Christianity, until She was tossed out. Let’s face it, if the women of the time were treated like baggage, enslaved, and considered property, how could one employ a female divinity in one’s religion? If She really existed, wouldn’t She be a bit testy on the treatment of Her energy made flesh? Let’s just ignore Her, they said, and maybe She will go away.

Or not.

The point here is to tell you that the belief that She exists isn’t something new, strange, or anti-religious. She was here first, and She will be the last to go, no matter what anyone tries to tell you, simply because everyone needs the perfect mommy.

Recommended Reading

Drawing Down the Moon by Margot Adler

The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft by Ronald Hutton

The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe: Myths and Cult Images by Marija Gimbutas