Fig. 7.1 Diagrammatic representation of structure of subjective mental symptoms

Neuroimaging in psychiatry: Epistemological considerations

Ivana S. Marková and German E. Berrios

There is little doubt that the development of neuroimaging technologies has transformed understanding, research, and practice in medicine. The resolution power of MRI or fMRI enables the visualization of tissues, organs, and metabolic activity in fine detail and has resulted in clarification of anatomical structures and the biochemistry of physiological processes. Brain structure has been a particular focus of such research and, in the last decades, this has been extended to brain function. This, however, has raised new epistemological challenges. Whilst brain structure, whether at the level of organ, tissue, cell, or other, lends itself well to instrumental visualization, the capture of brain “function” demands additional conceptual justification. And, when it comes to “higher brain functions” or cognitive functions (such as working memory, problem solving, perception, etc.), neuroimaging techniques are beset by even more complex conceptual problems (Faux 2002; Uttal 2001, 2004). This notwithstanding, the claim by many that it is possible to capture or “localize” cognitive functions (e.g., Jezzard and Buxton 2006) has encouraged the application of these techniques to abstract concepts such as self-reflection (van der Meer et al. 2010), vocal deception (Spence et al. 2008a), self-knowledge (Ochsner et al. 2005), guilt/innocence (Spence et al. 2008b), morality (Decety and Cacioppo 2012), etc. and also to psychiatric symptoms and psychiatric disorders.

In recent years, therefore, there has been much research effort dedicated to the localization of psychiatric symptoms and disorders to brain structures and neuronal circuitry (e.g., Allen et al. 2008; Alvarenga et al. 2012; Brambilla et al. 2009; Drevets 2001; Hulshoff Pol et al. 2004; Shad et al. 2012; Tanskanen et al. 2010). Remarkably, however, relatively little interest has been directed at questions concerning the validity of such research enterprises, that is, at questions about whether and/or to what extent it makes sense to try to capture psychiatric objects (mental symptoms and mental disorders) using techniques designed to capture physical structure and physiological processes (e.g. Honey et al. 2002). This is even more surprising given major disagreements about the definition, identification, and classification of mental symptoms and uncertainties about the “nature” of mental disorders and their neurobiological correlates. Indeed, the enthusiasm and rapidity with which the new technologies have been applied to psychiatric objects suggests that much has been invested in the hope that the high-level resolution power of these technologies will silence conceptual misgiving and provide answers to the problems of mental disorders and symptoms which so far have eluded the psychiatric discipline.

Setting aside for the moment the conceptual problems underlying such enthusiastic research drive, it is important to highlight at the outset a worrying consequence of it, namely, the desire to bestow on neuroimaging data a sort of wholesale validity that threatens to undermine the very ontology of the original “psychiatric” data. In other words, according to the “neurorealist” view (Racine et al. 2005), the very existence and legitimacy of mental symptoms and disorders is being made to depend upon their capture by neuroimaging. Taken to its extreme, it would follow that if patients’ complaints do not correlate with the requisite brain circuitry, then such complaints would be deemed irrelevant or non-existent. The paragon of “valid” mental phenomena would thus be determined by what is captured by neuroimaging. In this new world, subjective experience and subjectivity in general would be relegated to being a trivial non-scientific discourse. A similar point has been made in relation to the neuroimaging of pain (see Hardcastle and Stewart 2009). The newly proposed Research Domain Criteria for the classification of psychiatric disorders (RDoC) exemplifies well this way of thinking. Taking a “precision medicine” approach, this project by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) sets out a new method of classifying mental disorders based on: “levels of analysis progressing in one of two directions: upwards from measures of circuitry function to clinically relevant variation, or downwards to the genetic and molecular/cellular factors that ultimately influence such function” (Insel et al. 2010: 749). In other words, and in direct reversal of the conventional approach, the starting point in the exploration of mental disorders and symptoms becomes neurobiology or neural circuitry (Cuthbert and Insel 2013). In order to achieve a more “scientific” and objective classification of mental disorders, the authors suggest a transfer of the gold standard of validity from the psychiatric complaint to the “data captured by neuroimaging” and other “neuronal dysfunction” measures. Thus, data whose only claim to validity is that they correlate with real-life complaints are made to become now the gold “standard” against which the reality of complaints (by future patients) should be assessed and judged. It remains an important question as to what might be the epistemological arguments to warrant such devaluation of the patient’s subjectivity.

The issue here seems to be that against a background of perceived lack of “scientific” progress in the understanding of psychiatric disorders, the advent of neuroimaging technologies has seemingly provided an alibi to transform a hypothesis into a law of nature. In other words, the desideratum that psychiatric disorders may only consist in disruptions of neurobiological systems (Cuthbert and Insel 2013) is suddenly converted into a foundational claim. This carries implications not only for decisions concerning what constitutes mental symptoms and mental disorders, and the ways in which these should be researched, but also for the very language with which these are expressed and understood.

It is not the aim of this chapter, however, to focus on the consequences of this particular approach to the exploration of mental symptoms and disorders. Ultimately this should be determined by its predictive validity and therapeutic usefulness for patients. Instead, this chapter wishes to address the question of the epistemological quality of the neuroimaging of psychiatric objects (mental symptoms and disorders), or to put it another way, to what extent psychiatric objects lend themselves to valid neuroimaging. This question can be examined from various standpoints, but here it will be restricted to one level of analysis, namely, to an exploration of the sorts of objects or structures psychiatric objects are and, in the light of this, whether it is possible for them to be mapped onto specific brain systems. The issue alluded to earlier, as to whether it makes ethical sense to convert the meanings that human beings and societies have developed to understand and communicate about themselves and the world into the language of neurobiology, is an important one, but demands a different level of analysis and will not be covered here.

Why an epistemological perspective? An epistemological approach examines the grounds on which knowledge in relation to things can be developed and understood. It lays out the presuppositions on which the knowledge is based and the conceptual framework within which it operates. This becomes particularly important in relation to psychiatric objects which are not easily locatable in standard classifications that include organic material (e.g., brain tissue, cells, etc.), functional processes (e.g., blood flow, glucose metabolism), functional events (e.g., sneezes), and abstract entities (e.g., virtues, selves). Yet, if any sense is to be made of research that attempts to correlate psychiatric objects with neurobiological objects, then it is imperative that the structure of psychiatric objects can be understood if not to the same level of sophistication, then at least to a clearer conception of their constitution (Marková and Berrios 2009, 2012). Only then can the validity of neuroimaging research in psychiatry be delineated. As indicated earlier, there has been relatively little interest taken in this question and most work questioning the use of neuroimaging in psychiatry has tended to focus predominantly on methodological problems relating to the use of techniques such as scanning the environment, selecting appropriate cognitive tasks, and achieving statistical power (e.g., Kanaan and McGuire 2011).

The chapter considers the question of whether and/or to what extent psychiatric objects are structurally suited to the project of localization and neuroimaging. Focusing thus solely on the nature of psychiatric objects (mental symptoms), there is no space given here to the distorting effects generated by their transformation into proxy variables for mapping purposes. In other words, the whole issue of proxyhood, that is, how symptoms are actually represented for mapping purposes (e.g., scores on questionnaires), although important, will not be covered here. It goes without saying that issues concerning proxyhood play a significant part in epistemological considerations of neuroimaging research, since the representational quality of all the proxy variables entering into both sides of the correlation (complaint and brain) will be a determining factor of the validity of the results obtained. However, in order to highlight the importance of knowing something about the psychiatric objects entering into such correlations we will concentrate only on the role their structures play in trying to map them to brain processes.

Lastly, there will be no discussion of problems associated with the interpretation of neuroimaging data. This is a major area in itself and has been covered in detail elsewhere (e.g., Heeger and Ress 2002; Logothetis 2008; Price and Friston 2002; Sutton et al. 2009). The chapter is divided into two parts. The first examines the nature of psychiatric objects. For reasons of space, it will concentrate only on mental symptoms and will argue that these should be viewed as hybrid objects. The second will deal with the implications that the hybrid nature of psychiatric objects has on their putative brain inscription.

The question as to what kind of objects are mental symptoms can be looked at from different perspectives. One can, for example, focus on whether mental symptoms represent changes (impairments or exaggerations) in ordinary mental functions or whether in fact they represent something quite different. Since the late nineteenth century this has been a debate that remains to be resolved (Berrios 1996), though much of neuroimaging research is based on the assumption that mental symptoms are expressions of ordinary mental functions that have become pathological (e.g., Halligan and David 2001). The focus here, however, will be on trying to determine what kind of structures mental symptoms might be, how they compare with other structures, and, in particular, what are the features of structures that make them amenable to capture by instruments such as neuroimaging machines.

In general terms mental symptoms as currently listed are divided into subjective mental complaints, that is, those that are expressed by patients (e.g., low mood, interference with thinking), and “objective” signs/behaviors, that is, those that are observed by clinicians (e.g., psychomotor retardation, flight of ideas). For reasons of space, only subjective mental symptoms will be examined here.

Subjective mental complaints are those that are expressed by the patient, whether volunteered or elicited through questioning. They include, for example, depressed mood, anxiety, hearing voices, feelings of unreality/strangeness, experiencing thoughts being put inside one’s head, feelings of anger, feeling that familiar people are strangers, being unable to move or talk, fatigue, experiencing the world as strange and people as persecutors, and many more. It is evident that these “symptoms” are heterogeneous, differing in many ways. Thus, some refer to familiar mental states, ones that most people can relate to (e.g., worries, irritability, low mood), whilst others refer to strange, alien experiences (e.g., feeling that messages are coming into one’s stomach from a particular agency). Some relate to everyday events whilst others incorporate fantastical contents. Some are expressed directly as the “symptom” (e.g., anxiety, depression) whilst others are labeled as symptoms by the clinician on the basis of how they are expressed (e.g., delusions). Some seem to be feelings, others seem to be beliefs or perceptions, and others seem to be mixtures of many or all. Some might be volunteered freely whilst others are elicited with difficulty. Some are uttered easily and others might be expressed with hesitancy and uncertainty, and so on. Whilst they all fall within the current grouping of subjective mental symptoms, clearly they are very heterogeneous phenomena (Marková and Berrios 1995).

The question here is what sort of “objects” are they? What are they made up of? How can this be determined? One useful way of thinking about this is considering how they might arise. By definition, subjective mental states (whether “symptoms” or ordinary mental states) must refer to states about which people are aware. In other words, when people complain of low mood or a sense of unreality or hearing voices, then this is something that they are saying on the basis of their interpretation of some internal experience. The cause of this experiential change makes little difference at this point. It could be the result of an acute stressor or trauma, or ongoing pressures in one’s life, or some form of brain condition, or indeed combinations of such factors in the context of genetic vulnerability and so on. The point is, however, that there must be some awareness of experiential change which at its earliest can be envisaged as an inchoate, pre-linguistic, pre-conceptual state (Berrios and Marková 2006). How, then, does such an experiential change become converted into a subjective mental symptom?

It would seem likely that in order to make sense of this change and to articulate this, individuals will have to draw on a variety of sources. First of all there will be sources that relate to the individual and his/her sociocultural background. Here, factors such as past experiences, personality traits, personal biases and outlooks, levels of education, media influences, peer pressures, social contexts, language skills, and many more will all be important in shaping the experiential change into an articulated “symptom.” For example, a history of past similar experiences or knowledge of others with what seem like similar experiences might facilitate interpretation of some states such as depressed mood or anxiety. A tendency to introspection might generate more detailed and colorful expressions of some experiences. The level of education or interest in reading might determine the range of vocabulary an individual has to describe what he/she is experiencing. The family, society, and culture in which the individual is brought up will help to structure and color the interpretation he/she makes of the internal state. Thus, in a society where it is frowned upon to express feelings explicitly, it might be more likely that an emotional experience is understood and described in cognitive terms. Or, a culture lacking in obvious ways of articulating emotional distress might encourage descriptions of specific experiences in somatic terms, such as fatigue, pain, etc. In other words, in the same way that individuals will report on an external event in different ways, individuals will likewise interpret and make sense of changes in their conscious states according to their personality and sociocultural background.

Second, factors around the development of the experiential change will play a part. Here, in the first place, the rate at which this change in conscious state occurs must be important. A change in an internal state that builds up slowly might draw on more sources such as memory, emotion, knowledge, etc. to make sense of this than an internal state that changes very rapidly. In the second place, the particular context in which it happens may also influence the way in which an individual will interpret this and understand it as an experience. In the third place, the quality of the change in conscious state will also play a part in how the internal state is interpreted. Something that is experienced as familiar might be more easily interpreted than something that is novel or alien, which might require effort to make sense of and need additional sources (e.g., cultural factors, imagination, etc.) to construct.

Third, in addition to these factors, there will be interactional forces that are also likely to be important in making sense of a particular internal state. Here, for example, the dialogical encounter may be vital in contributing to the shaping and articulation of the mental phenomenon. Thus, whether in communication with a clinician or with someone else, a nebulous, initially strange experience that the patient may have difficulty in capturing might, through the encounter itself, become crystallized into a specific “symptom,” as the mutual exchange may offer descriptions or meanings which resonate with the patient. Likewise, in some cases it might be that noticing a particular response in the interlocutor (e.g., the clinician may appear more interested or understanding in relation to certain terms) might encourage the use of a specific description by a patient which subsequently becomes fixed as a symptom. Similarly, in the interaction with the environment and context, sense may be “constructed” of a particular internal experience. Furthermore, whilst here, for the sake of analysis, examination is focused on how single symptoms might arise, in reality symptoms do not occur in isolation but alongside multiple other “symptoms” and variable mental state changes. Interaction, with whatever else is being experienced at the time, must also be important in shaping the description of the final symptom.

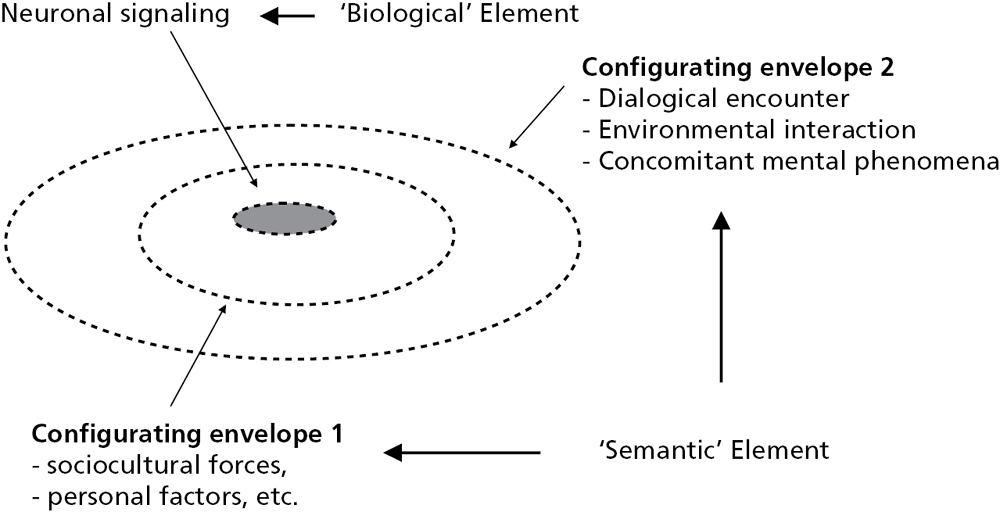

The question, then, is what does this all mean for understanding the structure of subjective mental symptoms? So far it would seem that there are many different kinds of factors or forces which will affect the way in which individuals will make sense of and articulate changes in their internal states. However, from this we can identify two basic elements. First, there has to be some core of neurobiology or brain signaling, since it goes without saying that all mental activity is underpinned by brain activity. Second, there is the “meaning” element, the product of all the different factors involved in shaping and formulating an experience. Thus we have a “biological” element and, what for the sake of brevity, can be called a “semantic” element, on the understanding that this refers to meaning in the broadest sense of the term as determined by the aforementioned forces relating to individual, sociocultural, and interactional factors. This can be represented by the following diagram (see Figure 7.1):

Fig. 7.1 Diagrammatic representation of structure of subjective mental symptoms

The figure is a schematic representation of the structure of a subjective mental symptom as constituted by a “biological” element and the “semantic” element. The latter is depicted in the form of two constructive “envelopes.” The first one represents the configuration that occurs as a result of the individual and sociocultural forces (i.e., factors relating to personality, past experiences, education, personal biases, etc.). The second one represents the configuration that occurs as a result of interactional forces (i.e., through interaction with people, with the particular environment and/or context, and with concomitant mental experiences). What is evident from the process, though difficult to illustrate diagrammatically, is that the structure of the final subjective symptom must represent a product of the interaction between biological processes and the meaning that is configured on the basis of multitudinous factors.

The world is populated by all sorts of objects which, at different times, might become the subject of scientific enquiry. In general, objects may exist in time, in space, and in combinations of these. The question of what constitutes an “object” and how objects are classified has itself been an area of much debate (see Ferrater Mora 1991). For the purposes here, “object” simply refers to “a thing or being of which one thinks or has cognition, as correlative to the thinking or knowing subject; something external or regarded as external to the mind” (Oxford English Dictionary 1989). (It has to be understood that whilst subjective mental symptoms are by definition “mental,” that is, within the mind so to speak, nevertheless, as “objects of enquiry” (e.g., as correlational variables of neuroimaging techniques) they become objects in a putative “external” space.) Defined in this way, objects have been classified into (i) physical or natural and (ii) abstract or ideal. Physical or natural objects refer to objects which exist in time and space such as houses, trees, clouds, brains, cells, atoms, etc. As such, providing there are the technologies available, they can be visualized at some level—whether this is by eye, by ruler, by microscope, or by any other instrument—and hence captured and measured accordingly.

Abstract or ideal objects refer to objects such as virtue, numbers, morality, beauty, etc. Unlike physical objects, these do not exist in space. They are constructs, that is, objects created by society and culture in order to help describe or explain aspects of life and the world. As they do not exist in space, such objects cannot be instrumentally visualized and captured. One cannot take a picture of e.g. morality or examine virtue with a microscope or X-ray tube. Such objects cannot be defined or measured in such physical ways. Individuals can relate to the concept of beauty, but will find different things beautiful and/or beautiful to differing extents.

What about subjective mental symptoms, then? How do subjective mental symptoms compare with other “objects”? Unless one takes a position of extreme reductionism, materialism, or physicalism, then they don’t seem to belong to the physical kinds of objects such as trees or atoms. Neither, however, can they be viewed as entirely abstract or ideal objects. Instead, as complexes of the biological (physical) and the “semantic” (constructed meanings), they seem to share features of both. In other words, they would appear to be hybrid objects. Hybrid refers to “anything derived from heterogeneous sources, or composed of different or incongruous elements” (OED 1989). Since subjective mental symptoms appear to be constituted by biological elements on the one hand, and “semantic” elements on the other, thus seemingly derived from heterogeneous sources and incorporating incongruous elements, then they must be considered as hybrid. The fundamental question that naturally arises from this conception of mental symptoms as hybrid is one that concerns the relationship between these two incongruous elements. How do the biological and “semantic” elements relate to each other?

Vital for any brain localization project has to be some understanding of the relationship between the biological and the “semantic” elements constituting the mental symptom. Where there is a relatively direct relationship between the biological and “semantic,” that is, where specific neuronal signaling is consistently correlated with a specific “meaning,” then clearly this would give localization efforts some justification. However, the problem emerging from examining how certain mental symptoms might arise is that it cannot be assumed that the relationship between the biological and “semantic” is always that direct or that consistent.

We have seen that many different kinds of factors are likely to influence the interpretation of a particular internal state, and whilst such factors (sociocultural, individual, interactional, etc.) will themselves be underpinned by neurobiological activities, such configuration does preclude a specific and direct relationship between a “final mental symptom” and a particular neurobiological signal. Questions pertaining to the directedness and specificity of the “biological–‘semantic’” relationship need dealing with because their answers will help with understanding: 1) the vexed problem of brain localization, 2) the structure of hybrid objects, and 3) the role that components play within each symptom, thereby determining the sense of the symptom as a whole.

The term “sense” is used here in this specific way in order to differentiate between the different aspects of meaning that are being referred to in this chapter. To restate, the term “semantic” refers to the meaning derived from one of the structural constituents of the mental symptom. Since, as has been shown, this is configured by diverse factors spanning individual, sociocultural, and interactional sources, the meaning contained in “semantic” is wide. In contrast, the term “sense” refers to the meaning of the symptom as a whole and specifically how, as a “research variable,” the symptom can be understood and handled.

Given the heterogeneity of mental symptoms, it would seem likely that the nature (directedness) of the relationship between their biological and “semantic” components, and hence the role of each, will also be complex and variable. Some symptoms may have a relatively direct relationship between a specific biological signal and a specific associated meaning. In this case, the biological element may have the greater role and will carry the sense of the symptom. In other symptoms, this relationship is not direct on account of the influence of the configuring factors. Here the “semantic” element will have the greater role and will carry the sense of the symptom. It is the sense of the symptom that should determine the type of research approach taken to its study.

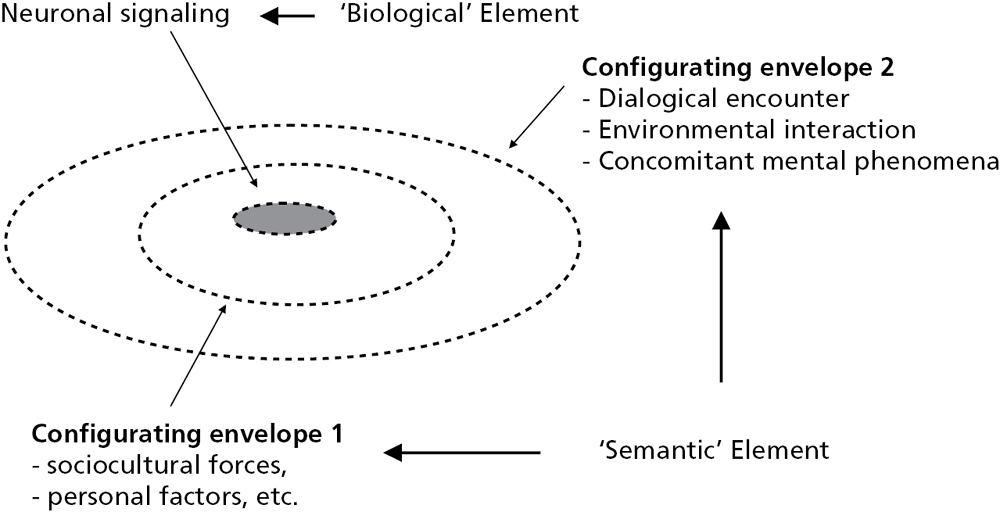

Elsewhere, it has been proposed that from a structural point of view, mental symptoms might usefully be divided into those which have primary brain inscriptions and those which have secondary brain inscriptions according to the directedness of the “biological–‘semantic’” relationship (Berrios and Marková in press) (see Figure 7.2).

Fig. 7.2 Schematic representation of mental symptoms with primary and with secondary brain inscriptions

Mental symptoms with primary brain inscriptions are those which correspond in time and space with the brain activity that gives rise to them. Here there would appear to be a direct and specific relationship between the biological and the “semantic.” For example, an ictal focus or brain lesion in a particular area might directly trigger organic hallucinations. Or, perhaps some of those symptoms that are directly “observed” or captured by the clinician, such as flight of ideas or psychomotor retardation might more likely be associated with specific reproducible brain activity—as such symptoms will not have been subject to the sort of interpretative and constructive forces within the individual. (There would of course be other factors to take into account in these situations, such as the interpretative factors on the part of the clinician which may also serve to “distort” the ensuing symptom (Berrios and Marková 2002)—but this will not be examined here.) The sense of the symptom in these cases would be carried predominantly by the “biological” element and thus have less in the way of a meaningful connection for the individual. In other words, irrespective of how the symptom is expressed, it can be viewed as more stereotypical and relatively empty from personal significance.

On the other hand, mental symptoms with secondary brain inscriptions are those symptoms where the relationship between the biological and “semantic” is not direct. Here, the brain representations can be viewed as simply the concomitant neurobiology substratum. In other words, the biological is the non-specific brain activity that accompanies mental activity. In this case, the sense of the symptom is carried predominantly by its “semantic” element. Here, the meaning is important from the point of view of understanding its connection to the individual. This may or may not carry personal significance. For example, an individual in the context of depression and on the basis of a particular internal state might articulate a symptom of “guilt.” Various sources will have been important in configuring it as such, including perhaps past experiences, personality factors, recent events, peer pressure, etc. Such factors within the individual and his/her sociocultural background will, by constructing the experience, serve to connect the individual with the symptom in a deep sense. When, in addition, the symptom carries a personal value, e.g., if the guilt refers to perceived failures in life as opposed to a non-specific feeling, then the connection becomes personally significant. The important issue, however, is that the connection to the individual may lead to the clarification of the symptom in terms of its “semantic” roots.

If subjective mental symptoms are considered hybrid objects, what, then, are the implications of this fact for their localization in the brain and hence for neuroimaging? We have shown that as hybrid objects, subjective mental symptoms consist of biological and “semantic” elements. We have also suggested that the nature of the relationship between the biological and “semantic” determines the sense of the symptom, that is, the particular locus of the symptom that carries its meaning. Based on this, it was proposed that mental symptoms might usefully be divided into those with primary brain inscriptions and those with secondary brain inscriptions—on the understanding that mental symptoms are likely to fall within a range between these “prototypes.” Brain localization involves the mapping of, in this case, a subjective mental symptom onto a specific neuronal structure or circuitry. The manner in which the biological and the “semantic” are related within each particular mental symptom thus becomes crucial to making possible and to understanding the brain localization endeavor.

In the case of mental symptoms with primary brain inscriptions, here it was argued that the relationship between the biological and “semantic” elements of the symptom was relatively direct and specific. Thus, picking up neurobiological activity can be said, relatively speaking, to be tantamount to capturing the sense of the symptom. In other words, from a theoretical perspective and without considering the other factors creating noise in this sort of correlational exploration, it could be argued that these types of mental symptoms might be amenable to brain localization projects.

In the case of mental symptoms with secondary brain inscriptions, here the sense of the symptom as a whole is carried by the “semantic” element of the symptom structure. The neurobiology, whilst present, does not have the direct and specific relationship with the “semantic” aspect of the symptom. It follows that the “same” neurobiological signal may be associated with a number of different symptoms—as individuals will configure their internal states differently according to the influences of the sorts of factors mentioned earlier, such as past personal experiences, sociocultural backgrounds, interactional effects, and so on. Thus, one patient might complain of low mood whilst another one talks of pain or anxiety or depersonalization, etc. Conversely, “different” neurobiological signals may be associated with the “same” mental symptom. The issue is that trying to map such mental symptoms onto specific neurobiology is fraught with problems. Sprevak (2011) argues for the importance of interactional effects between cognition and the contextual environment, neatly showing how neurobiology is not sufficient to explain specific cognitive processes. In relation to more complex mental phenomena, such interactions will be magnified in scope. Capturing the neurobiology, no matter how sophisticated the technology, may have little bearing on the meaning of the symptom itself. Since the “semantic” element of such symptoms carries the greater role, the sense of the symptom lies in the constructive forces that have played a part in its constitution. Research directed at understanding such symptoms should be aimed instead at developing new hermeneutical approaches which could seek to disentangle such constructive forces. Determining any neurobiological correlates of such symptoms with neuroimaging technologies is unlikely to add to the understanding of these symptoms and could only have limited validity in terms of mapping the structures involved.

Research aimed at the neuroimaging of mental symptoms must therefore consider very carefully the specific mental structures under enquiry. As was shown, it may be that those symptoms whose sense is carried by the biological element might more readily lend themselves to neuroimaging projects. Thus, in terms of such research, careful selection of symptoms would be imperative. In turn, identifying these will necessitate further research, both conceptual and empirical.

The recognition that from a structural perspective not all mental symptoms lend themselves to brain localization, and hence to neuroimaging research, carries wider implications. In the first place, it opens up new directions for the exploration and understanding of mental symptoms. As mentioned previously, consideration of the sorts of factors contributing to the “semantic” constituent of particular mental symptoms raises possibilities of developing different hermeneutical approaches for clarification of their nature as symptoms. In the second place, there are therapeutic implications in that the management of those symptoms whose sense is carried by the “semantic” element may need more than “biological” treatments to alleviate them fully. Thus research aimed at disentangling the meaningful constituents of such symptoms may lead to new ways of their management. In the third place, and from a wider perspective still, understanding symptoms as hybrid and their consequent relationship with neurobiological circuitry obviates the need for the assumption that all mental disorders are neurobiological disorders. This assumption, which is the driving force behind much of the neuroimaging work, is a major assumption and carries the potential of steering research in psychiatry into blind alleys (Berrios and Marková 2002). By contrast, highlighting the differential roles of the biological and the “semantic” in conveying the sense of mental symptoms not only draws attention to the different relationships between biological processes and meanings, but opens up the possibilities of examining these relationships from any causative direction (particularly relevant in relation to the question of psychogenesis).

Much research effort and funding is directed at neuroimaging in psychiatry, driven amongst other things by the successes obtained by such technologies in medicine as well as by the belief that mental disorders are neurobiological disorders. It has been argued here that consideration must be given to both these claims to determine the validity of such research. First, psychiatry is a hybrid discipline, in a stronger and deeper sense than medicine. Its objects (mental symptoms and mental disorders) are likewise hybrid in structure, that is, they are made up of incongruous elements. Focusing here on subjective mental symptoms, such elements were identified as biological on the one hand and “semantic” on the other, the latter referring to the complex meaning that is constructed from the interaction of multitudinous factors including individual, sociocultural, and interactional. On account of this structure, mapping to brain structure and function becomes problematic and raises questions about the meaning of the results obtained. The validity of localization projects and thus neuroimaging research must depend on careful selection of “appropriate” mental symptoms.

Second, it has to be understood that the claim that mental disorders are neurobiological disorders is simply an assumption. It can only be considered trivially true in the sense that all mental states are underpinned by neurobiology. An epistemological clarification of how mental symptoms are structured and formed is crucial for determining valid approaches to both empirical research and clinical management.

Allen, P., Larøi, F., McGuire, P. K., et al. (2008). The hallucinating brain: a review of structural and functional neuroimaging studies of hallucinations. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 32, 175–91.

Alvarenga, P. G., do Rosário, M. C., Batistuzzo, M. C., et al. (2012). Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions correlate to specific gray matter volumes in treatment-naïve patients. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46, 1635–42.

Berrios, G. E. (1996). The History of Mental Symptoms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Berrios, G. E., and Marková, I. S. (2002). Conceptual issues. In H. D’haenen, J. A. den Boer, and P. Willner (eds), Biological Psychiatry (pp. 3–24). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Berrios, G. E., and Marková, I. S. (2006). Symptoms—Historical Perspective and Effect on Diagnosis. In M. Blumenfield and J. J. Strain (eds), Psychosomatic Medicine (pp. 27–38). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Berrios, G. E., and Marková, I. S. (2014). Towards a New Epistemology of Psychiatry. In L. J. Kirmayer, R. Lemelson, and C. Cummings (eds), Revisioning Psychiatry. Cultural phenomenology, Critical Neuroscience and Global Mental Health. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Brambilla, P., Bellani, M., Yeh, P. H., et al. (2009). White matter connectivity in bipolar disorder. International Review of Psychiatry, 21, 380–6.

Cuthbert, B. N., and Insel, T. R. (2013). Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Medicine, 11, 126.

Decety, J., and Cacioppo, S. (2012). The speed of morality: a high-density electrical neuroimaging study. Journal of Neurophysiology, 108, 3068–72.

Drevets, W. C. (2001). Neuroimaging and neuropathological studies of depression: implications for the cognitive-emotional features of mood disorders. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 11, 240–9.

Faux, S. F. (2002). Cognitive neuroscience from a behavioural perspective: a critique of chasing ghosts with Geiger counters. The Behavior Analyst, 25, 161–73.

Ferrater Mora, J. (1991). Diccionario de Filosofía. Círculo de Lectores, Barcelona.

Halligan, P. W., and David, A. S. (2001). Cognitive neuropsychiatry: towards a scientific psychopathology. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2, 209–14.

Hardcastle, V. G., and Stewart, C. M. (2009). fMRI: a modern cerebroscope? The case of pain. In J. Bickle (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Neuroscience (pp. 179–99). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Heeger, D. J., and Ress, D. (2002). What does fMRI tell us about neuronal activity? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3, 142–51.

Honey, G. D., Fletcher, P. C., and Bullmore, E. T. (2002). Functional brain mapping of psychopathology. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 72, 432–9.

Hulshoff Pol, H. E., Schnack, H. G., Mandl, R. C., et al. (2004). Focal white matter changes in schizophrenia: reduced interhemispheric connectivity. Neuroimage, 21, 27–35.

Insel, T., Cuthbert, B., Garvey, M., et al. (2010). Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 748–51.

Jezzard, P., and Buxton, R. B. (2006). The clinical potential of functional magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 23, 787–93.

Kanaan, R. A. A., and McGuire, P. K. (2011). Conceptual challenges in the neuroimaging of psychiatric disorders. Philosophy, Psychiatry & Psychology, 18, 323–32.

Logothetis, N. K. (2008). What we can do and what we cannot do with fMRI. Nature, 453, 869–78.

Marková, I. S., and Berrios, G. E. (1995). Mental symptoms: are they similar phenomena? The problem of symptom heterogeneity. Psychopathology, 28, 147–57.

Marková, I. S., and Berrios, G. E. (2009). Epistemology of mental symptoms. Psychopathology, 42, 343–9.

Marková, I. S., and Berrios, G. E. (2012). Epistemology of psychiatry. Psychopathology, 45, 220–7.

Ochsner, K. N., Beer, J. S., Robertson, E. R., Cooper, J. C., Gabrieli, J. D. E., Kihlstrom, J. F., and D’Esposito, M. (2005). The neural correlates of direct and reflected self-knowledge. NeuroImage, 28, 797–814.

Oxford English Dictionary, Second edition (1989). Oxford UK: Oxford University Press.

Price, C. J., and Friston, K. J. (2002). Functional neuroimaging studies of neuropsychological patients: applications and limitations. Neurocase, 8, 345–54.

Racine, E., Bar-Ilan, O., and Illes, J. (2005). fMRI in the public eye. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6, 159–64.

Shad, M. U., Keshavan, M. S., Steinberg, J. L., et al. (2012). Neurobiology of self-awareness in schizophrenia: an fMRI study. Schizophrenia Research, 138, 113–19.

Spence, S. A., Kaylor-Hughes, C., Farrow, T. F. D., et al. (2008a). Speaking of secrets and lies: the contribution of ventrolateral prefrontal cortex to vocal deception. NeuroImage, 40, 1411–18.

Spence, S. A., Kaylor-Hughes, C. J., Brook, M. L., et al. (2008b). ‘Munchausen’s syndrome by proxy’ or a ‘miscarriage of justice’? An initial application of functional neuroimaging to the question of guilt versus innocence. European Psychiatry, 23, 309–14.

Sprevak, M. (2011). Neural sufficiency, reductionism and cognitive neuropsychiatry. Philosophy, Psychiatry & Psychology, 18, 339–44.

Sutton, B. P., Ouyang, C., Karampinos, D. C., et al. (2009). Current trends and challenges in MRI acquisitions to investigate brain function. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 73, 33–42.

Tanskanen, P., Ridler, K., Murray, G. K., et al. (2010). Morphometric brain abnormalities in schizophrenia in a population-based sample: relationship to duration of illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36, 766–77.

Uttal, W. R. (2001). The new phrenology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Uttal, W. R. (2004). Hypothetical high-level cognitive functions cannot be localized in the brain: another argument for revitalized behaviorism. The Behavior Analyst, 27, 1–6.

van der Meer, L., Costafreda, S., Aleman, A., et al. (2010). Self-reflection and the brain: a theoretical review and meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies with implications for schizophrenia. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 34, 935–46.