“What does making sculpture mean to you right now?”, Richard Serra was asked in 1976. With only a decade of mature work behind him, he replied: “It means a life-time involvement, that’s what it means. It means to follow the direction of the work I opened up early on for myself and try to make the most abstract moves within that. To work out of my own work, and to build whatever’s necessary so that the work remains open and vital …”1 Much in this statement holds true many years later. “Opened up” suggests that his work develops from salient predecessors—not only such sculptors and painters as Constantin Brancusi and Jackson Pollock, but, as we will see, particular architects and engineers as well—predecessors whom Serra strives both to displace, in order to make a space of his own, and to carry forward. “[T]he most abstract moves” underscores that this carrying forward brooks no return to figurative traditions, pictorial conventions of figure-and-ground or even Gestalt readings of images. “[T]o work out of my own work” indicates that his art, once opened up, is driven by its own language more than by any precedents. Yet, lest this language become involuted, the work must also remain “open and vital” through building—through the exigencies of actual materials, projects, and sites. The statement thus points to three dynamics that have governed his art since its opening up, three forces of which it is the fulcrum: engagement with particular precedents; elaboration, through pertinent materials, of an intrinsic language; and encounter with specific sites.

In 1986, ten years after this statement, the Museum of Modern Art mounted an exhibition titled “Richard Serra: Sculpture.” What is the relation posed by the colon? In a title like “Piet Mondrian: Painting,” it reads almost as an equation, a reflexive relation of immanent analysis, with painting refined by Mondrian to its essential lines and primary colors. This relation was supported by a medium-specific paradigm of modernist art that does not hold for the generation of Serra. He might still ask the ur-modernist question “What is the medium?” but his response does not aim for an ontology of sculpture in modernist fashion. Serra does not evade the medium; on the contrary, he is singularly committed to its concept (unlike his peers in Minimalism, Fluxus, Arte Povera…). Yet this category has changed, in part through the force of his example, and today sculpture is not given beforehand but must be proposed, tested, reworked, and proposed again.2 This is the modus operandi of his work.

In 1965 Donald Judd could state flatly that “the specific objects” of Minimalism were “neither painting nor sculpture.”3 On the one hand, sculpture had contracted to the space between an object and a monument, the restrictive coordinates given by Tony Smith for his six-foot steel cube Die (1962).4 On the other hand, it had stretched to the point where great expanses could be contemplated as sculpture, or at least as its site; the notorious example, again offered by Smith, was the unfinished New Jersey Turnpike.5 Not a few artists became lost in the arbitrary realm of this expanded field. However, for the more astute the ramifications of Minimalism were more precise: a partial shift in focus from object to subject, or from ontological questions about the nature of the medium to phenomenological conditions of particular bodies in particular spaces—which effectively became the new ground of sculptural art. This shift was fundamental for Serra, and he has developed its logic further than anyone else—that is, within the category of sculpture. At the same time Serra was critical of Minimalism, skeptical about the non-transparency of its construction as well as its preoccupation with painting. Although the Minimalist object is often called sculpture, it developed primarily from Color-Field painting à la Barnett Newman, as evidenced by the early work of Judd alone. For Serra, even though the unitary forms and serial orderings of Minimalist objects were pledged against the relational composition of painting, they remained bound up with its pictorial conventions. Like his peers, he wanted to get beyond this pictorialism, especially as it underwrote Gestalt readings of art, which he saw as idealist totalizations that serve both to conceal the construction of the work and to suppress the body of the viewer.6 Yet Serra wanted to defeat this pictorialism completely, and in sculptural terms. What might this mean?

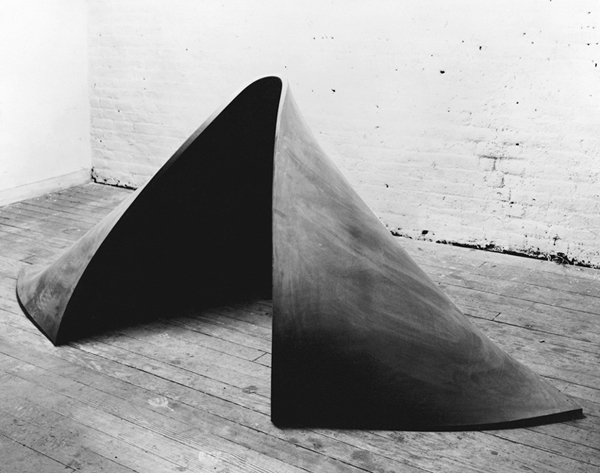

In 1966, when Serra first opened up his work, it meant that the Minimalists had obviated sculpture more than exceeded it. (This was hardly their doing alone: many Conceptual, performance, mixed-media, and installation artists would do the same thing.) So the question became: How might one proceed differently, sculpturally, to develop the category deconstructively rather than to declare it void triumphally? In response Serra stressed, beyond the point of Minimalism, the very terms that were suppressed in both dominant models of modernism and Gestalt readings of art, terms like materiality, corporeality, and temporality. First, in lieu of a logic of medium-specificity, he substituted a logic of materials, of specific materials submitted to specific procedures. Hence his well-known “Verb List” (1967–68)—“to roll, to crease, to fold …”—which issued in several kinds of work: sheets of lead rolled, torn, or otherwise manipulated; molten lead splashed along the base of a wall and peeled back in rows; slabs of concrete stacked or sheets of lead propped; and so on.7 These processes transformed the traditional object of sculpture, and they led Serra to particular works that opened up distinctive lines of investigation. After the art historian George Kubler, he calls them “prime objects” inasmuch as “they present each problem in its greatest simplicity.”8 Thus To Lift (1967), a signal piece in process art in which the action of the title is performed on a thick sheet of rubber, first raised the question of surface typology for Serra. House of Cards (1969), made up of four four-foot squares of lead that support one another, set up all the prop pieces that rise from the floor. Strike (1969–71), a single plate of steel, eight feet high, that juts out twenty-four feet from its bisected corner, prepared all the wedges and arcs that cut into space. To Encircle Base Plate Hexagram, Right Angles Inverted (1970), a steel circle, twenty-six feet in diameter, embedded in a street in the Bronx, first established physical site as fundamental to his practice. And so on.9

Strike: To Robert and Rudy, 1969–71. Hot-rolled steel. 8 × 24 feet × 1 ½ inches. Photo Peter Moore.

To Lift, 1967. Vulcanized rubber. 36 × 80 × 60 inches. Photo Peter Moore.

Yet not all results avoided pictorial associations, as Serra acknowledged in a self-critique of 1970: “A recent problem with the lateral spread of materials, elements on the floor in the visual field, is the inability of this landscape mode to avoid the arrangement qua figure ground: the pictorial convention.”10 Characteristically, rather than pull back, he pushed forward, and highlighted the very term, ground, that seemed most problematic. For Serra this emphasis on place was signaled by Carl Andre in the middle 1960s with his arrangements of bricks and plates, and then confirmed in 1970 through his encounters with Spiral Jetty (1970) by Robert Smithson in Utah, Double Negative (1969–70) by Michael Heizer in Nevada, and, above all, Zen gardens and temple complexes in Japan (especially Myoshin-ji in Kyoto). All three instances pointed to a condition of “the discrete object dissolved into the sculptural field.”11

One Ton Prop (House of Cards), 1969. Lead. Four plates, each 48 × 48 × 1 inches. Photo Peter Moore.

Rock garden in Myoshin-ji temple complex, Kyoto.

With this opening to field, two terms emerged with renewed force for Serra: the body of the viewer and the time of bodily movement.12 After such sited works as Shift (1970–72) and Spin Out: For Bob Smithson (1972–73), Serra was prepared, in 1973, to describe “the sculptural experience” in terms of a “topology of [a] place” demarcated “through locomotion,” a “dialectic of walking and looking into the landscape.”13 In this way sculpture became a parallactic operation, in which the work frames and reframes the subject and the site in tandem, and it guided Serra after his breakthrough in 1970, not only in pieces placed in a landscape so as to reveal its topology (from Shift, say, to Sea Level [1988–96]), but also in works positioned in an urban context so as to reframe its structures (from Sight Point [1972–75] to Exchange [1996]), as well as in pieces set in an art space so as to refocus its parameters (from Strike [1969–71], say, to Chamber [1988]). Of course, place is fundamental to all this work, yet, as Rosalind Krauss has argued, site-specificity is not its end so much as its medium; or, more precisely, its medium is “the body-in-destination” in a particular site, and in this respect the body remains as primary as place.14 Thus emerged a revised formulation of sculpture as a relay—a relay between site and subject that (re)defines the topology of a specific place through the motivation of a specific viewer.

Shift, 1970–72. Concrete. Six sections. King City, Ontario.

So by 1976, when the question “What does making sculpture mean to you right now?” was asked, certain emphases were already clear. First, the stress on making—on the verb or sculptural process, rather than the noun or categorical medium—was correct. This making led Serra to foreground materials such as lead and steel, which were inflected by pertinent procedures into motivated structures. This became the first principle of sculpture for Serra, and it might be called “Constructivist,” for it concentrates, as Russian Constructivists like Vladimir Tatlin did, on the expressive development of structures out of the appropriate treatment of materials (which the Constructivists called construction and faktura respectively).15 The second principle, which might be called “phenomenological,” was that sculpture exists in primary relation to the body, not as its representation but as its activation—its activation in all its senses, all its apperceptions of weight and measure, size and scale. The third principle, which might be called “situational,” was that sculpture engages the particularity of place, not the abstraction of space, which it redefines immanently rather than represents transcendentally. Together these principles have guided Serra ever since in his understanding of sculpture as a structuring of materials in order to motivate a body and to demarcate a place.

Sight Point (for Leo Castelli), 1972–75. Weatherproof steel. Three plates, each 40 × 10 feet × 2 ½ inches. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

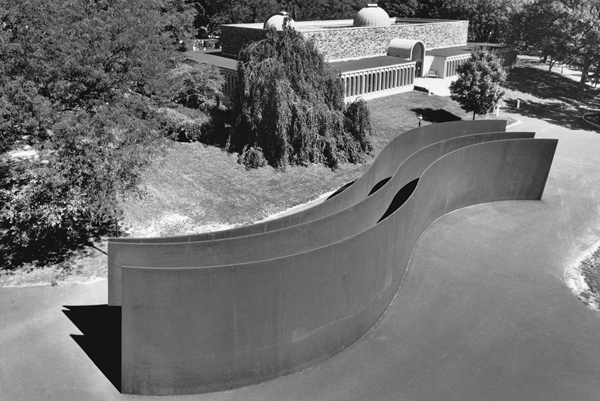

This provisional definition of sculpture also suggests a partial typology of work since the 1970s, which includes landscape markings, urban framings, and gallery interventions. Examples of each category include, respectively, Afangar (1990) positioned on an Iceland island, Torque (1992) placed at a German university, and Sub-tend 60 Degree (1988) set in a Dutch museum. Serra expanded this typology in subsequent decades. On the one hand, he returned to early modes, such as his props, to reconnect with his basic syntax of “pointload, balance, counter-balance and leverage.”16 On the other hand, he elaborated subsequent modes, such as his arcs, in new ways. Serra first tilted the arcs, then doubled and trebled them, then waved them so as to form a new type, the serpentine ribbons. These ribbons bow in and out in such a way as to suggest corridors and enclosures; the torqued ellipses and spirals also produce passages and surrounds at the same time. So, too, as if to counterpoint these complex manipulations, Serra elaborated other types like the rounds and blocks which, rather than frame space, concentrate it through sheer mass.17 This is what it is to develop a sculptural language.

The Hedgehog and the Fox, 1998. Weatherproof steel. Three plates, each made up of two identical conical/elliptical sections inverted relative to each other, 15 ½ × 91 ½ × 24 ½ feet × 2 inches. Princeton University, New Jersey.

Yet a paradox remained: Serra insisted that his work was strictly sculptural, while his best critics regarded it as a deconstruction of sculpture.18 The paradox was only apparent, however, for with Serra sculpture effectively becomes its deconstruction, its making becomes its unmaking. For sculpture to harden into a category is for sculpture to become monumental again—for its structure to be fetishized, its viewer arrested, its site forgotten, again. In this light, to deconstruct sculpture is to serve its “internal necessity” (to evoke an ur-modernist formulation), and to extend sculpture (in relation to process, body, and place) is to remain within it. This is to say, finally, that Serra turned a paradox into a dialectic, one focused first on the question of site.

“The biggest break in the history of sculpture in the twentieth century,” Serra has remarked, “occurred when the pedestal was removed”—an event that he understands as a shift from the memorial space of the monument to the “behavioral space of the viewer.”19 This shift was a dialectical one, which opened up another trajectory, too, for with its pedestal removed, sculpture was free not only to descend into the materialist world of “behavioral space” but also to ascend into an idealist world beyond any specific site. Consider how Brancusi, the most significant prewar sculptor for Serra and his peers, developed this dialectic. With his ambition to convey near-Platonic ideas—the idea of flight, say, in the ascendant arc of Bird in Space (1923)—his work is an epitome of idealist sculpture. At the same time it celebrates sheer material, and his bronzes are often polished to the point where they reflect their environment. Brancusi also articulated this dialectic in the particular terms of the pedestal: some of his pieces absorb the base of the sculpture into its body, as it were, with the effect that sculpture becomes siteless, as in Bird in Space, while others appear to be nothing but base, nothing but support, as in Caryatid (1914).20 In this way Brancusi was as committed to the idealist realm of the studio (he bequeathed his own space to France as his ultimate work of art) as he was to the specific siting of abstract sculpture (as in his complex of pieces in Targu Jiu, Romania). Once-dominant accounts of modernism privileged the idealist side of this dialectic, the hypostasis of sculpture as pure form. As a critical counter to this position, Serra and his peers developed its materialist side—of sculpture plunged into its support and re-grounded in its site—which is one reason why this collective work stands as a crux between modernist and postmodernist art.21

Of course, the antinomy between idealist and materialist impulses is also active in modern philosophy and, indeed, in modern society at large. More salient here is the contradiction between the artisanal, individualistic basis of traditional sculpture and the technological, collective basis of industrial production. In industrial society old paradigms of sculpture—of plaster, marble, bronze or wood, modeled, carved, cast or cut—were destined to become archaic; indeed, for Benjamin Buchloh these models were “definitely abolished by 1913” with the advent of the first readymade by Duchamp and the first construction by Tatlin.22 Such materialist paradigms repositioned sculpture subversively in terms of epistemological inquiry (the readymade) and architectural intervention (the construction), with the consequence, according to Buchloh, that sculpture faced “the eventual dissolution of its own discourse as sculpture.”23 Predicated as they were on the old idealist models, most Western institutions (museum and academy alike) overlooked these materialist paradigms. Nonetheless, the contradiction between artisanal sculpture and industrial society hardly disappeared; it persisted, even in the very practices that sought to resolve it—that is, to reconcile individual craft and collective industry through various versions of welded sculpture, found objects, and assemblage, all of which mix signifiers of craft and industry alike. (Buchloh cites Julio Gonzalez, David Smith, John Chamberlain, and Anthony Caro in particular, figures whom Serra has questioned to different degrees as well.)24

Constantin Brancusi, Bird in Space, 1923/1941. Polished bronze. 56 ¾ × 6 ½ inches. © CNAC/MNAM/Dist. Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY.

In the 1960s, however, artists such as Judd, Flavin, Andre, Robert Morris, and Serra both recovered and related the models of the readymade and the construction. They did so in ways that served not only to deconstruct the idealist presuppositions of most autonomous sculpture, but also to demystify the quasi-materialist compromises of most welded sculpture, found objects, and assemblage—“literally to ‘decompose’ ” these mythical models through the direct exposition of industrial materials, processes, and sites.25 Again, Serra and his peers also pushed the situational aspect of sculpture, after its break with the pedestal, to the point where this break, which was only announced in 1913 with the readymade and the construction, became actual by 1970, with new site-specific practices.26 Yet in what sense, then, did these practices remain “sculpture”—a term some of these artists abjured or at least avoided?

For Serra, too, the initial project was to demystify modernist models, to defetishize them along Constructivist lines. “In all my work,” he wrote in an important text of 1985, “the construction process is revealed. Material, formal, contextual decisions are self-evident. The fact that the technological process is revealed depersonalizes and demythologizes the idealization of the sculptor’s craft.”27 Note the last phrase in this statement. For some critics this categorical insistence on sculpture appeared to mythify the Constructivist demystification of the medium, in effect to turn this critique back into sculpture.28 For Serra, however, the insistence was necessary inasmuch as sculpture lacked a secure basis, a strong language, of its own, and it became his project to develop one.

“The origin of sculpture is lost in the mists of time,” Baudelaire wrote in one expression of this lack; “thus it is a Carib art.”29 Here, in a short section of his Salon of 1846 titled “Why Sculpture is Tiresome,” the great poet-critic repeats some tiresome complaints about sculpture: that it is too material, “much closer to nature” than painting, and too ambiguous, more unstable than painting because, as an object in the round, “it exhibits too many surfaces at once.”30 These criticisms adhere to the idealism not only of Hegel, whose hierarchy of the arts positioned sculpture below painting on account of its relative materiality, but also of Diderot, whose celebration of the tableau privileged the putative instantaneity of our experience of the singular surface of painting over the implicit duration of our experience of the “many surfaces” of sculpture. As we have seen, Serra and his peers challenged these persistent idealisms.31 But what about the provocative remarks about “lost origin” and “Carib art”? By “Carib” Baudelaire implies that sculpture is primitive, even fetishistic (he discusses fetishes in this same section of the Salon). In his time the fetish was understood as an impure thing, a hybrid object not worthy of the cult worship devoted to it, and in this regard it served as a discursive token of the lowest registers of world art and religion alike (as it does in Hegel, among others). Hence the “lost origin” of sculpture: Baudelaire suggests that its cultic beginnings as a fetish do not provide sculpture with an adequate basis to develop into a proper art.32 Obviously, Serra does not agree with Baudelaire; yet he, too, believes that sculpture does not possess a secure foundation, and so seeks a principle (or set of principles) that might stand in lieu of its “lost origin.” What is more, he uses its “Carib” status as material, impure, and hybrid to critical advantage in doing so.

Again, Serra presents a distinctive definition of sculpture: that it motivate a body and frame a place in a parallactic relay between the two. But he also positions sculpture between two other terms: opposed to painting on the one side, and critical of architecture on the other. In his Salon of 1846, Baudelaire calls sculpture a “complementary art,” “a humble associate of painting and architecture.”33 This is in keeping with the Hegelian hierarchy of the arts that ascends from architecture through sculpture to painting (and on to music, poetry, and finally philosophy).34 In effect Serra uses the middle term of this old hierarchy to pressure the adjacent terms. More precisely, he employs the relative materiality of sculpture, its ability to activate body and site, in order to critique painting (which does not perform this activation), and the relative autonomy of sculpture, its ability to demonstrate structure, in order to critique architecture (to the extent that it obscures its own tectonics). In the process Serra presents a further principle of sculpture, one that is not medium-specific but medium-differential, and that turns its “Carib” vice (again as impure and hybrid) into a critical virtue.35

Serra approaches this differential understanding of sculpture through a philosophical point of procedure drawn from Bertrand Russell. “Every language has a structure about which nothing critical in that language can be said,” Serra remarks; only a second language with a different structure can perform this analysis.36 He first adapted this principle in order to think through the relation of his drawings and films to his sculpture, but it also speaks to the relation of his sculpture to painting and architecture. On the one hand, Serra insists on the absolute status of sculpture as a language of its own; on the other hand, he manipulates this language to partake of aspects of painting and architecture, but only in order to articulate its differences from them. Thus, for example, even as his sculpture opposes painting to the degree that it resists figure-ground conventions, it also partakes of the pictorial in the sense of its framing of a site.37 And even as his sculpture critiques architecture to the degree that it refuses the scenographic, it also partakes of the architectural in the sense that it also privileges the structural.

Above I touched on the differences from painting, so here I will focus on the differences from architecture. Whatever its own restrictions, sculpture is less bound up with capitalist rationalization and bureaucratic regulation, and thus more free to intervene critically in other areas, not least in matters of architecture. Yet Serra suggests more: that sculpture can recover a neglected principle in architecture, in its tectonic basis, and recover it as a “lost origin” for sculpture. Often his sculpture “works in contradiction” to the architecture of its sites.38 This relation can be aggressive (it does not aid the destroyers of Tilted Arc [1981–89] to note that it questioned the banal architecture of the Federal Plaza in New York), but it can also be subtle, complementary, even reciprocal, whereby sculpture and architecture serve as foils for each other. Thus there are pieces (often arcs) that primarily frame architecture, such as Trunk (1987), first installed in a Baroque courtyard in Munster, Germany, and there are pieces (often blocks) that are primarily framed by architecture, such as Weight and Measure (1992), first installed in the neoclassical hall of the Tate Gallery in London; and there are pieces that do both, such as Octagon for Saint Eloi (1991), which stands in sympathetic rapport with the Romanesque church behind it. Sometimes in such historical settings a reversal of roles occurs, too: the sculpture seems to foreground the architecture, as with the two austere blocks of Philibert et Marguerite (1985) that throw into relief the ribbed vaulting of the sixteenth-century cloisters in which they are set.

Often, however, Serra relates to architecture in order to critique it, and this critique is of two kinds at least. The first is procedural, to do with basic modes of architectural representation: elevation and plan (that is, the structure of a building seen en face and its array of spaces seen from above). In his work, as Yve-Alain Bois has remarked, Serra often destroys, “in the very elevation, the identity of the plan,” and vice versa, with the result that neither presentation (in front or from above), neither view (from outside or inside), delivers the other, let alone the sculpture as a whole.39 Serra intends this impediment as a way not only to resist the becoming-image of the work but also, in so doing, to reassert the rights of the body against the abstract objectivity (even the panoptical mastery) of architectural representation. The second critique is polemical, to do with the superficiality of postmodern architecture. There are two primary targets here: its privileging of scenography over structure (“most architects,” Serra remarked in 1983, in the postmodern heyday, “are not concerned with space, but rather with the skin, the surface”) and its masking of consumerism as historicism (“symbolical values have become synonymous with advertisements,” he commented in 1984).40 Thus his stress on the tectonic has a double edge: it addresses the historical absence of the tectonic in sculpture—which, again, it proposes as a “lost origin”—and it questions the recent atrophy of the tectonic in architecture.

Octagon for Saint Eloi, 1991. Weatherproof steel. 6 ½ × 8 × 8 feet. Eglise Saint Martin, Chagny, Saône-et-Loire, France.

Another key term in the lexicon of Constructivist art, the tectonic is also advanced in architectural discourse, especially by Kenneth Frampton. His argument is polemical, too: like Serra, Frampton assails the scenographic kitsch of much postmodern architecture, and he insists on the bodily and the tectonic in protest against the capitalist technologies of the simulacral and the virtual that much architecture has lately embraced.41 Yet his argument is also ontological in a way that differs from Serra: “the structural unit,” Frampton states, is “the irreducible essence of architectural form.”42 In fact Frampton projects an origin myth of architecture (along the lines of “the primitive hut” advanced by Abbé Laugier in the service of neoclassical architecture): after Gottfried Semper, Frampton believes that architecture is founded in the apposition of a compressive mass (as exemplified in brick construction) and a tectonic frame (as exemplified in wood construction). Thus, for Frampton, “the very essence of architecture” is located in “the generic joint,” and this “fundamental syntactical transition from the stereotomic base to the tectonic frame” becomes “a point of ontological condensation.”43 According to Frampton, this apposition of mass and frame is not only material (brick versus wood) and “gravitational” (heavy versus light) but also “cosmological” (earth versus sky), with “ontological consequences” that are transcultural and transhistorical in value.44

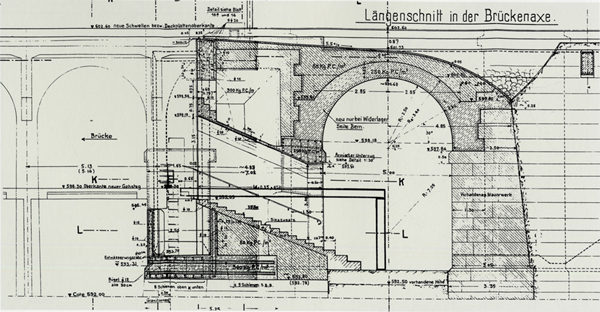

Much here is resonant for a reading of Serra, though, again, he stops well short of the metaphysics entertained by Frampton. The joint is crucial in his work, too; left bare, not welded, the intersection of his steel plates is where structure reveals production most clearly, and demystifies old modes of sculpture in doing so. Louis Kahn liked to say that ornament is the adoration of the joint; for Serra, “any kind of joint—as necessary as it might be for functional reasons—is always a kind of ornament,” and he respects it precisely through his exposure of it, his refusal to “ornament” it at all.45 So, too, the coordination of mass and frame in Frampton, which occurs paradigmatically at the joint, may correspond to the coordination of “weight and measure” in Serra. Certainly the relation of load and support is fundamental to his work, and his lead and steel props in particular subsume the tectonics of wood and the stereotomics of brick (Serra calls the prop “the most basic of engineering principles”). Above all Serra joins Frampton in his insistence on the tectonic. This, too, is most apparent in the props (to which he returned in the late 1980s as if to offer a counter-example to the flimsiness of postmodern architecture), for, again, the props demonstrate his “building principles” of “pointload, balance, counter-balance, and leverage” most directly. Other works, especially of the late 1980s, declare these principles as well: works such as Gate (1987), which consists of two Ts of steel bars on either side of a gallery beam (they appear almost to support the ceiling); Timber (1988), a T of steel plates also set under a gallery ceiling; T-Junction (1988), another T of steel bars, set short of the gallery ceiling, in which the horizontal element is extended; and finally Maillart (1988), in which this horizontal element is extended even further, supported by two bars, in a structure that suggests a bridge (as does the titular reference to the great Swiss engineer Robert Maillart [1872–1940]).

However, there remains this obvious difference: Frampton claims the tectonic for architecture, Serra for sculpture. How to decide between the two? Perhaps there is no need to do so; perhaps architecture and sculpture have a common ground in the tectonic; perhaps in an industrial age they might even share an originary principle in engineered construction.46 Serra is forthright about his commitment to engineering, as in his statement from 1985:

The history of welded steel sculpture in this century—Gonzalez, Picasso, David Smith—has had little or no influence on my work. Most traditional sculpture until the mid-century was part-relation-to-whole. That is, the steel was collaged pictorially and compositionally together. Most of the welding was a way of gluing and adjusting parts which through their internal structure were not self-supporting. An even more archaic practice was continued: that of forming through carving and casting, of rendering hollow bronze figures. To deal with steel as a building material in terms of mass, weight, counterbalance, load-bearing capacity, point load has been totally divorced from the history of sculpture, whereas it determines the history of technology and industrial building. It allowed for the biggest progress in the construction of towers, bridges, tunnels, etc. The models I have looked to have been those who explored the potential of steel as a building material: Eiffel, Roebling, Maillart, Mies van der Rohe. Since I chose to build in steel it was a necessity to know who had dealt with the material in the most significant, the most inventive, the most economic way.47

Despite the predominance of European figures in his tectonic pantheon, an American mythos is at work here: long before Duchamp, in defense of his urinal, nominated plumbing and bridges as the great American contributions to civilization, Walt Whitman had sung the praises of the Brooklyn Bridge (as would Hart Crane and Joseph Stella later), and Serra participates in this ethos of building as an analogue of self-building.48 Also germane here are certain aspects of his personal formation, which include memories of his father as a pipe-fitter in a San Francisco shipyard and experiences as a young laborer in steel mills in the Bay Area.

The very insistence on the tectonic, in Serra as in Frampton, speaks to its atrophy in recent practice. In this respect another story might be in play here—that of a “dissociation of sensibility” between architecture and engineering on the one hand, and between sculpture and engineering on the other.49 The first dissociation is sometimes dated, emblematically at least, to the foundation of the École Polytechnique in France in 1795, when training in these fields was divided. The second dissociation never occurred because sculpture and engineering were never united in the first place: again, “steel as a building material … has been totally divorced from the history of sculpture.” So, unlike Frampton, who sometimes dreams of a rapprochement between architecture and engineering, Serra has no fall to redeem, only an opportunity to exploit, as the separation of sculpture from engineering was a historical given. Thus he was free to rework sculpture vis-à-vis engineering so as to render it pertinent to an industrial age. This reorientation, which is essential to his originality, runs throughout his work, but it is programmatic in a piece like Maillart Extended (1988), a post and lintel of steel bars that extends the pedestrian walkway across the Grandfey Viaduct (1925), designed by Maillart in Switzerland, in a sculptural way that reveals its structural logic.50

Drawing for Maillart Extended, 1988. Grandfey Viaduct, Switzerland,

There is a risk here, however: again, Serra might demystify sculpture as artisanal craft, only to mythify it as industrial structure. In effect this is to turn on Serra his own critique of welded sculpture—that it is a compromise-formation between art and industry—and to suggest that his productivist aesthetic, now outmoded, conceals more than it reveals the contemporary relation between art practice and productive mode in society at large. Yet this productivist aesthetic was not outmoded when Serra emerged in the middle 1960s (again, Russian Constructivism was only recovered from relative oblivion by his generation of artists and historians). “We came from a postwar, postdepression background,” Serra once remarked of a group including Andre and Morris, “where kids grew up and worked in the industrial centers of the country.”51 As noted in Chapter 7, they brought this frame of reference into artistic practice in ways that transformed the parameters not only of its materials and processes but also of its siting and viewing—the expanded scale of the work in loft studios, its opening to distant landscapes, its encounter with urban architecture, and so on.

Obviously much has changed over the last fifty years. Our economy has shifted to a largely postindustrial order of consumption, information, and service, which alters the relative position occupied by Serra and his peers.52 However, in this context his commitment to industrial structure might be seen as resistant not only to the pervasive decay of the tectonic in architecture, but also to its putative outmoding in a postindustrial order of digital design.53 In other words, if the industrial model of the tectonic is now outmoded in part, it might be strategic to reassert its claims; it might even be endowed with a new critical force.54 Certainly Serra can be taken to rebuff not only the scenography of most postmodern architecture but also the “novel tectonics” of much contemporary design, with its fascination with extreme engineering (Rem Koolhaas in his CCTV in Beijing) and/or digital image-making (Zaha Hadid in nearly all her work).55

The Drowned and the Saved, 1992. Weatherproof steel. Two right-angle bars, each 56 × 61 × 13 ¾ inches. Kirche St Kolumba, Erzbischöfliches, Diözesanmuseum, Cologne.

In the 1990s Serra pushed the tectonic element of his sculpture to other ends, two of which could not be expected, for each appeared as a dialectical transformation of prior concerns. First, there were works, such as The Drowned and the Saved (1992) and Gravity (1993), the first positioned temporarily in the Stommeln Synagogue in Germany, the second permanently in the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, that develop the symbolic associations of the tectonic in ways that point to spiritual meanings—not in opposition to secular conditions of sculpture, body, and site, but by means of them. In such pieces the spiritual is not imaged (this taboo remains in force), but it is evoked, and, though this evocation is not monumental (this restriction is also secure), it is commemorative. This is a commemoration expressed in “weight and measure” alone; rather than refer to an event elsewhere, the memorial is immanent to the structure.56 Second, there were works, such as the torqued ellipses, in which structure, in pace with engineering, is complicated to the point of a new order of effect: these pieces are so physically intense that they become psychologically intense, too. Like the commemorative turn, this psychological development was a surprise, given the avoidance of private spaces of meaning in much Minimalist and Postminimalist art, yet this psychological dimension is not necessarily a private one.57

In the Western tradition, Rosalind Krauss has argued, a monumental logic governed official sculpture, at least in the paradigmatic form of the statue, which “sits in a particular place and speaks in a symbolical tongue about the meaning or use of that place.”58 Modernist sculpture broke with this logic not only in its abstract forms and found materials but also in its break with the pedestal, which, again, was a dialectical event that opened sculpture to the possibilities of both modernist sitelessness and postmodernist site-specificity. In certain works of the 1990s, Serra posed a further transformation of these terms: a sculptural paradigm that is neither siteless nor site-specific, but both autonomous and grounded in other ways.

Gravity, 1993. Weatherproof steel. 12 × 12 feet × 10 inches. U.S. Holocaust Museum, Washington, D.C.

This direction became apparent in the early 1990s with works placed before a French church (Octagon for Saint Eloi), within a German synagogue (The Drowned and the Saved), and at the Holocaust museum in Washington (Gravity). Such sites are not strictly private or public, but potentially intimate and communal nonetheless. The Drowned and the Saved suggests a commemoration of the Holocaust by place as well as by title (which alludes to the great memoir of the Shoah by Primo Levi). Again, this subject is not imaged but evoked through structure alone, in which two L-beams (the horizontal longer than the vertical) support one another through abutment. Serra once termed this bridge form a “psychological icon”; it is emblematic of spanning and passing, and both kinds of movement are intimated here.59 There are those who cross the bridge, who pass over the abyss—the saved—and those who are not allowed to cross, who are dragged under—the drowned. These two passages, these two fates, are opposed, but they come together, as the two beams come together, in mutual support. In this way the tectonic principle first articulated for the props in 1970—“as forces tend toward equilibrium the weight in part is negated”—takes on a spiritual significance, for in this support there is a reciprocity that intimates a reconciliation of the drowned and the saved.60 This is a reconciliation, not a redemption: again, the grace is immanent, not transcendental; it depends on the gravity of the structure, to which it is equal and opposite. Like the Holocaust, both exist in our space-time—in history, not beyond it.

If The Drowned and the Saved foregrounds measure, Gravity foregrounds weight, which also takes on a spiritual significance.61 Gravity is a massive plane that steps down from the Hall of Witnesses in the Holocaust museum to the floor below; the psychological icon here is not a bridge but a stairway, which has symbolic associations of its own. Does this stepped plane intimate descent or ascent? Does it express gravity or grace? Although movement is implied by the steps, it is also stilled by the plane, and in such a way that oppositions of descent and ascent, of gravity and grace seem suspended (another symbolic form is in play here, too: the memorial wall). Pieces like Gravity and The Drowned and the Saved indicate a partial shift from a parallax of subject and site to an arresting of the viewer before the work. This arresting can be felt negatively, with Gravity seen as a wall and The Drowned and the Saved as a bar—that is, as so many blockages evocative of a traumatic reality that cannot be assimilated. Or this arresting can be felt positively, as a symbolic constellation of the sacred and the secular.62 Like the arresting of the viewer, the abstraction of the work, which here seems to follow spiritual as well as aesthetic principles, is also effective in its ambiguity.63 Is this refusal of representation vis-à-vis the Holocaust a sign of impossibility, of melancholic fixation on a traumatic past, or is it a sign of possibility, of a mournful working-through of this past that is also a holding-open to a different future? In either case the Shoah is commemorated, but not raised to the oppressive status of a religion of its own.64

Weight and equilibrium, gravity and grace, have effects that are psychological as well as bodily and spiritual. In 1988 Serra recalled a childhood memory of a ship launching at the yard where his father worked:

It was a moment of tremendous anxiety as the oiler en route rattled, swayed, tipped, and bounced into the sea, half submerged, to then raise and lift itself and find its balance … The ship went through a transformation from an enormous obdurate weight to a buoyant structure, free, afloat, and adrift. My awe and wonder at that moment remained. All the raw material that I needed is contained in the reserve of this memory which has become a recurring dream.65

One need not turn to a psychoanalysis of screen memories and primal fantasies to register the psychological impact of this event, and, though this dimension surfaced strongly in the late 1980s, it was latent in previous work.66 Indeed, from the beginning Serra and such peers as Robert Smithson, Bruce Nauman, and Eva Hesse were ambivalent about the apparent rationalism of Minimalism. On the one hand, their project was also rational: to foreground process in order to demystify the viewer about the making of sculpture. On the other hand, this making indicated a bodily engagement that often implicated the erotic and the psychological (this is most evident in Hesse, but it is present in the others, too).67 In the work begun with the torqued ellipses, Serra folds the rational and the irrational into one another. The rational aspect—to manifest production and structure—remains; but the irrational aspect—to disorient the viewer with the insides turned out and the outsides in—is pushed to the point where one seems to experience different sculptures at almost every step. That is to say, as Serra increases complexity, he does not forfeit legibility; he tests the viewer more rigorously than heretofore (he calls this “thinking on your feet”), but he also allows the viewer more choice, even more agency, as he or she looks, moves, feels, and reflects.

“The generation of the 1960s made an art of the human subject turned inside out,” Krauss has argued, “a function of space-at-large.”68 This remains the case with Serra, but the opposite has become true as well: with the torqued pieces the viewer appears to be inside and outside the sculpture at once, so that the subject-turned-inside-out is also a space-turned-outside-in, as if it, too, were made a function of the subject. In this way, Serra has opened up a psychological spatiality in his work, one of evocative interiors often associated with Surrealism; this was not to be predicted, for, as we have seen, Serra long plied the Constructivist line of modernism, which is contrary to the Surrealist trajectory. Yet, as he has developed this Constructivist line, he has also transformed it to the point where it is no longer strictly opposed to its old other.

This convergence of contrary trajectories attests to the semi-autonomy of artistic development won by Serra. Again, this practice deconstructs sculpture vis-à-vis its site, but in a way in which unmaking is not opposed to making any more than a commitment to site-specificity is opposed to the category of sculpture.69 Indeed, this semi-autonomy of the work is crucial to its site-specificity, as it must be if site-specificity is to be site-critical as well. This point—that semi-autonomy can be the guarantee of criticality, not its undoing—is often lost in recent developments in site-oriented and project-based work, which sometimes threatens to dissolve artistic practice into sociological or anthropological fieldwork. Serra has always stressed the internal necessity of sculpture, always insisted on the uselessness of art in general. Here this necessity, that uselessness, does not void the criticality of art; Serra shows that it can also underwrite it. Periodically, this is an important lesson to relearn.

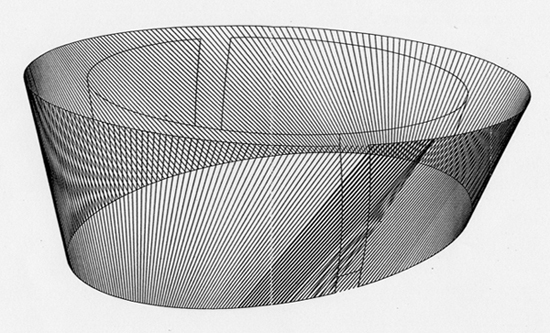

CATIA printout of Double Torqued Ellipse, 1998. Outer ellipse 14 × 37 ½ × 40 feet; inner ellipse 14 × 20⅓ × 32 feet.

To understand how a sculpture is constructed is not necessarily to know how it is configured, and just as Serra exploited the tension between conception and perception in his early work, so he has exacerbated the tension between structure and configuration in his later work. His multiple ribbons and torqued pieces are the results of this complication. In some ways these works suggest a Baroque counterpart to classical Minimalism: as in classical architecture, the Minimalist object engages the subject but remains external to him or her, while, as in Baroque architecture, the ribbons and the torques envelop the subject, and the effect is often an extraordinary chiasmus: a spatial overwhelming of the subject and a subjective deforming of space. In some ways it seems that the space is a projection of the body, a projection that one then experiences as if from the inside.

Etymologically, Baroque means “misshapen pearl.” However, Gilles Deleuze proposed “the fold” as a more apt term for its signal creations, whether these are taken to be the painting of Tintoretto, the architecture of Borromini, or the philosophy of Leibniz. For Deleuze a prime effect of the Baroque fold is to detach the interior from the exterior, “but in such conditions that each of the two terms thrusts the other forward.”70 Deleuze relates this effect to the art-historical schema of Heinrich Wölfflin (who established the classical/Baroque differential as a fundament of art history) as well as to the metaphysical reflections of Leibniz:

As Wolfflin has shown, the Baroque world is organized along two vectors, a deepening toward the bottom, and a thrust toward the upper regions. Leibniz [also] makes coexist, first, the tendency of a system to find its lowest possible equilibrium where the sum of masses can descend no further and, second, the tendency to elevate, the highest aspiration of a system in weightlessness, where souls are destined to become reasonable.71

Such a system of counterposed vectors and of mass that coexists with weightlessness returns with the torqued sculptures of Serra.

Serra has made this connection to the Baroque, too. For example, he tells us that the torqued ellipses were inspired in part by a momentary misrecognition inside the San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (1665–76), the Borromini church in Rome that is a masterpiece of Baroque architecture. One day in 1991 Serra entered the nave from the side, and mistook the ellipses of the dome and the floor to be offset in relation to one another:

The space rises straight up and doesn’t change in its regular oval form from top to bottom. It is kind of an “oval cylinder.” For me walking in from the side aisle was more interesting than standing in the central space. Then it occurred to me that I could possibly take what I perceived from the side aisle, and torque the space.72

In other words, Serra saw that he might twist in elevation such volumes as oval cylinders, ellipses, and spirals. First he tested this intuition with a model made up of two wood ellipses held parallel but askew to one another by a dowel. He made a template from this model, and a lead sheet was cut and rolled from it. His studio then applied a computer program to calculate the necessary bending of the projected ellipses at full scale, a bending that only a few steel mills in the world could then execute. This is how the torqued ellipses (first singles, then doubles) were generated, and the torqued spirals followed. In each instance there is a Baroque disconnection not only of elevation and plan but also of inside and outside.73

Double Torqued Ellipse II, 1998. Weatherproof steel. Outer ellipse 11 ¾ × 27 ½ × 36 feet; inner ellipse 11 ¾ × 28 ½ × 19 ½ feet.

This double disconnection already occurred in the multiple arcs, but they still carve out a principal trajectory that we can anticipate. This is not true of the torqued pieces; one cannot foresee or recall much about them (memory is tested here, too). The walls tilt in and out, left and right, sometimes together, often not; as a result they pinch, then release, and then pinch and release again, in ways that cannot be calculated precisely because they are torqued—that is, because the radii of the curves do not hold steady. There is no way to gauge the structure or the space ahead, and the same goes for the skin of the sculpture: “Because the surface is continuously inclined, you don’t sense the distance to any single part of the surface,” Serra comments. “It’s very difficult to know exactly what is going on with the movement of the surface.”74 One feels continuously dislocated, and even more so with the spirals, which, unlike the ellipses, do not have a common center and are not sensed as two discrete forms: thus it can seem that each new step produces not only a new space and a new sculpture, but even a new body. Sometimes, as the walls pinch, one feels the weight of the piece press down; but then, as the walls open up again, this weight is eased—it appears to be funneled up and away. Suddenly both body and structure feel almost weightless, and again even more so with the spirals, as they seem to spin more smoothly, more rapidly, as one walks through them.

Torqued Spiral (Right Left), 2003–04 (in foreground). Weatherproof steel. 14 × 46 ¼ × 43 feet × 2 inches. Guggenheim Bilbao.

Here Serra echoes archaic structures such as the labyrinth and the omphalos, structures that fascinated the Surrealists, too. But the torqued pieces are not mazes—one knows one is headed either toward or away from the openings—and the centers are without the oracular aura of the omphalos. Again, this quasi-Surrealist spatiality complicates his old commitment to Constructivist tectonics, yet a new language of building is forged in the process, one that undoes such old oppositions as rational and irrational, and mechanistic and biomorphic.75 At the same time the torqued pieces suggest futuristic structures as well, such as the “warped spaces” that permeate both computer graphics and contemporary architecture. Often in such design the subject is not situated, at least not in the manner of representational modes like perspective or of other mediums like painting or film; indeed, the apparent auto-generation of forms is almost oblivious to the subject, with the result that the subject can appear unfixed, almost elided.76 Serra evokes these effects in his torqued pieces, but only in order to check them in the interest of embodiment, placement, and context. As a result he stays clear of two pitfalls of neo-Baroque architecture today—its tendency to indulge in arbitrary forms and its tendency to efface the subject—even as he matches its provocative proposals about surface and speed.

Implicit here, then, is a further critique of recent architecture. With computer-assisted design and manufacture, it sometimes seems that any form can be conjured and built, and Serra points, by counter-example, to the waning of formal motivation and tectonic rationale that often results. This critique applies to recent art, too—especially practices involving projected images that are also inclined to an asubjective virtuality. With Serra, on the contrary, there is a layering, not a collapsing, of different spatialities and subjectivities, in a way that allows the complexity of experience to be sensuously retained, not futuristically flattened.