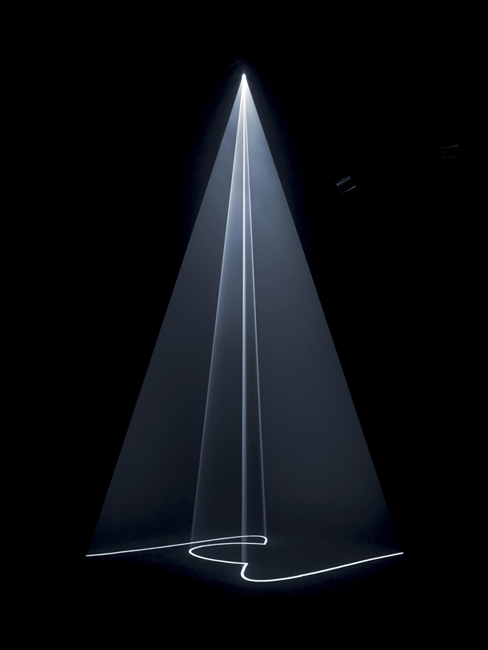

We enter a dark space to the whirr of a sixteen-millimeter film projector, and a pencil of white light cuts across the empty room to a distant wall. It registers as a dot, yet slowly the dot becomes an arc, and a small section of a cone is carved out of the space. As the thirty minutes of the film elapse, the arc grows into a circle, and a full cone of light is described in the room; then the process begins again. During the time of this describing we cannot help but touch the light as though it were a solid and investigate the cone as if it were a sculpture—cannot help but move in, through, and around the projection as though we were its partner, even its subject. Such is the experience of Line Describing a Cone (1973) by Anthony McCall, a classic of “structural film.”1

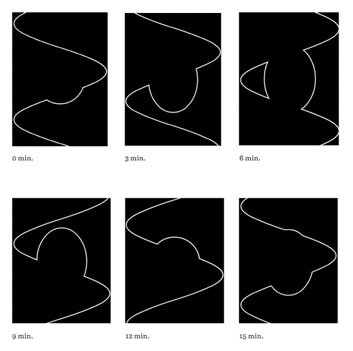

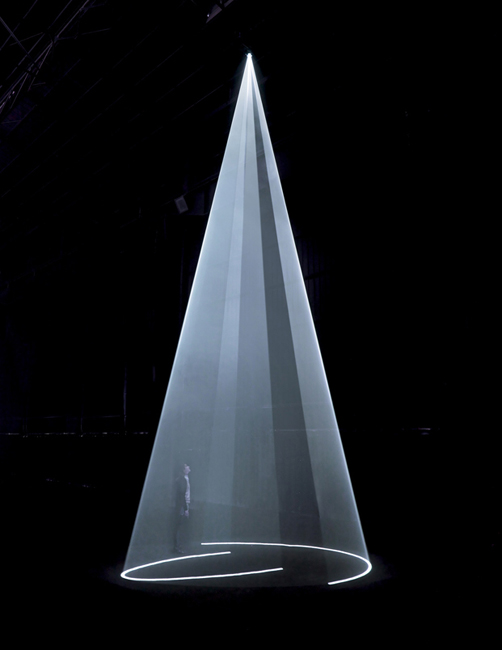

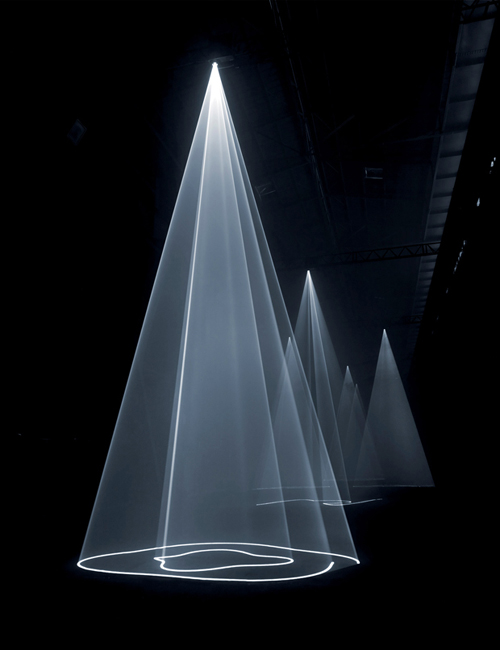

Fast-forward thirty-three years. Again we enter a dark space, but there is no sound, as the projector, now digital, is silent. There are two such machines, located above us, with the projected figure, also double, on the floor at our feet. This figure is far more complex than a line describing a cone: it has no obvious beginning or end, and its development cannot be readily anticipated; in fact it can scarcely be understood. As a result, over the sixteen minutes of this projection, we tend to observe the tracing on the floor more assiduously than we do with a horizontal piece like Line Describing a Cone, in order to tease out the logic of its configuration in time, a logic that also defines the moving veils of light that fall from above—though we know this correlation more than perceive it. Gradually (it requires more than one iteration), we see that one of the two figures is an ellipse that contracts and expands while the other figure, a wave, travels toward it; there is also a line that rotates through the wave, complicating both forms. At the same time a very slow filmic wipe connects the two figures such that the one is always eclipsing the other, making breaks, which produce apertures in the veils of light, and forging connections, which produce closures, in the process. Gradually, too, we see that, in the course of a cycle, one figure turns into the other: ellipse becomes wave and vice versa. This is the experience of Between You and I (2006), one of several vertical projections McCall has made since 2004.

Line Describing a Cone, 1973. 16 mm black-and-white film projection (30 minutes; here seen in the 24th minute). Photo Hank Graber.

Between the first series of films represented by Line and the second represented by Between, there was a long hiatus in this work (largely due to the falling away of support for structural film in the art world of the 1980s and 1990s); nonetheless, McCall calls them all “solid-light films.”2 Solid light is a beautiful paradox, one that conjures up the old debate about its nature (i.e. is light a particle or a wave?), and McCall invites us to play with the paradox—to touch the projections as if they were material even as our hands pass through them with ease, to see the volumes as solids even though they are nothing but light. The play is sensuous, to be sure, but it is also cognitive, for we are prompted to ask (as McCall does, rhetorically, here), “Where is the work? Is the work on the wall [or the floor]? Is the work in space? Am I the work?”3

Sequential frames of Between You and I, 2006.

In effect this is also to ponder, “What is the medium?” It is film, evidently enough, but film denatured, stripped bare, reduced to projected light in darkened space. At the same time film is expanded here, in the sense that it is made both to draw lines and to sculpt volumes. In the process it is also questioned, particularly in the recent projections, which are digital and so, technically speaking, not filmic at all (they have none of the slight flicker of the early pieces, for example); the vertical pieces disrupt the horizontal orientation of cinema as well.4 “I was certainly always searching for the ultimate film, one that would be nothing but itself,” McCall has recalled, and this ambition is in keeping with the modernist project of artistic reflexivity and autonomy.5 Finally, however, what is disclosed here is less any essence of film than the recognition that mediums do not operate in this way—that they are not so many nuts to crack, with a meat to eat and a shell to discard, but a matrix of technical conditions and social conventions in a differential relation to the other arts. Thus this search for the “ultimate film” implicates other mediums, too, which, like Richard Serra and others before him, McCall shows to be arrayed in an aesthetic field, one that significant practice always works to reconfigure and to renew.

Between You and I, 2006. Digital projection. Peer/The Round Chapel, London. Photo Hugo Glendinning.

Of course, the first art implicated here is cinema, even though McCall pares away most of the attributes associated with it, not only illusionistic space and fictional narrative but also the spectatorial precondition of this imaginary “elsewhere” (as he calls it)—that is, the viewer fixed in place (seated in fact), with eyes locked on the screen, and mostly oblivious to apparatus, ambience, and audience alike (the cone of projected light in particular).6 It is “the first film to exist in real, three-dimensional space,” McCall has asserted of Line, and it “exists only in the present.”7 This here-and-now-ness holds for his other films as well, and yet, as suggested, the effect is not to deliver film into a stable state of autonomous purity but to place it in correspondence with various arts—cinema first (especially in the horizontal projections), then sculpture (especially in the vertical projections), but other mediums and disciplines, too.8

“The body is the important measure,” McCall says of the dimensions of his projections. Not only do they assume its scale, but they also incite us to move with the light—to play and/or to experiment with it—as it moves in turn; again, we interact with a McCall film as though we were somehow its subject.9 This bodily reference is one key connection with sculpture; another is that the films also carve volumes out of space. Non-traditional genres are elicited as well; for example, when the projectors engage the floor, the films implicate installation, too.10 On this score, beyond sculpture and installation, the solid-light films invite us to think about the architectural parameters of the given venue, which they both obscure and illuminate in ways that make us sense the space haptically as well as optically—that is, to feel our way around it with our hands out and our eyes wide open. One could say more about the rapport of the projections with other disciplines. Again, just as the films sculpt space, they also trace lines, and so implicate drawing as well.11 In fact they are drawings in light, literal photo-graphs in motion (which is, after all, what film is), and so photography is also engaged. In many ways the great pleasure afforded by the work comes as we move from an experiencing of the different phenomenologies of these media to a puzzling over their provisional ontologies and back again. Sensuous and cognitive, the space of the solid-light films is thus philosophical, too.

This play with the aesthetic field began for McCall in the early 1970s, in close relation to the reflexive project of structural film (in which he participated in London and New York) as well as the expanded field of sculpture after Minimalism (which he experienced primarily in New York, where he has lived since 1973).12 McCall evidences his commitment to both practices in his belief that viewers of the early films tend to turn away from the projection and toward the projector in order to reflect on the reality of the apparatus rather than on the appearance of the image, like so many Platonic subjects no longer captivated by the imagistic illusion on the cave wall. This is not always the case, however: viewers also attend closely to the tracing, and, given the increased complexity of the vertical films, they do so even more so with these. That is, they play not only with the paradox of solid light but also with the tension between the film-as-drawing (“Is the work on the wall or the floor?”) and the film-as-sculpture (“Is the work in the space?”). This tension develops the one produced by many Minimalist objects—the tension between the known form and the perceived shape, between the given Gestalt and its multiple manifestations from various perspectives. As we saw in Chapter 8, this discrepancy is activated by the viewer set in motion by the object in space; with the solid-light films it is also produced by the movement of the projected figures. Indeed, as the figures become more intricate, the tension between the known and the perceived becomes more intense, but never to the point where the viewer feels overwhelmed by complexity or stunned by speed. This is so in part because McCall hews to the principle that the viewer should be “the fastest thing in the room,” lest one be arrested before the mobile figure and become a passive observer.13

The viewer, then, is not stopped by the films; again, one moves in and out of the projections, through and around them, in order to experience the manifold of time and space that they produce. This is also the case with later sculptures by Serra, whose torquing of ellipses and other shapes is clearly relevant to the recent films. Of course, light is permeable and mobile where steel is neither; nevertheless, some of the questions raised by the two artists are similar. For instance, with Serra one works to correlate the experience of his curved spaces, interior and exterior, with the image of the sculpture as a whole, or, in architectural terms, to correlate the elevation of the structure with its plan. With McCall, too, one strives to hold together the shapes of the light veils that fall from above with the patterns of the projected lines that are traced below; and, like Serra, McCall complicates this correlation as his work advances, as if to lead us, as students of his language, through a progression of encounters or examinations. In both cases the viewer is entrusted to learn each new piece, in effect to accompany the artist in the development of his compositions, and in this way a dialogical relation is set up with the oeuvre as a whole.14

This is also to say that the work tests the mettle of our visual skills. Just prior to Line Describing a Cone, Michael Baxandall published an influential study of Renaissance art, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy (1972), which argues that early Renaissance masters both assumed and advanced the quotidian talents of their viewers. The ability to gauge different sizes, as practiced at the marketplace, might also be summoned in the contemplation of spatial perspective, as before a painting by Piero della Francesca, say, or the ability to dance in complicated ensembles might also be tapped in the appreciation of figural groupings, as before a composition by Pisanello, say. “Much of what we call ‘taste’ lies in this,” Baxandall writes, “the conformity between discriminations demanded by a painting and skills of discrimination possessed by the beholder. We enjoy our own exercise of skill, and we particularly enjoy the playful exercise of skills which we use in normal life very earnestly.”15 The playful exercise of visual expertise is entertained by McCall, too, whose work offers a pleasurable pedagogy in properties of line, volume, space, and movement.16 Skills that range from basic Euclidean geometry to advanced mathematical equations are entertained here, and there is delight in this informal learning. The experience is also a sociable one: one can witness complete strangers debate the intricacies of the forms, and schoolchildren invent impromptu games in the volumes.

This intimate interaction, which is both private and public, is central to the experience of the solid-light films. They do invite us to ask, “Am I the work?”, but the question is not a solipsistic one; and, though we are placed within immersive environments, there is no oceanic feeling or sublime effect manufactured for us.17 At the same time the semi-paranoia of modern accounts of vision and visuality does not pertain either. Think of Heidegger on “the world picture”—his argument that perspective underwrote the modern view of the world as a technological “standing reserve” and of the individual as its instrumental master; or Sartre and Lacan on “the gaze”—their arguments that, even as we might assume this mastery over “the world picture,” we are also subject to it—subject to the gaze of the other (as in other people) as well as to the gaze as other (as in our inhuman surround that seems to observe us). “I am in the picture,” Lacan writes ominously, “I am photo-graphed” by the light of the world, queried in my lack by its gaze.18 This fearful inflection is also present in Foucault with his notion of an institutional gaze that disciplines us, and in feminist film theory with its demonstration that classic cinema positions us prejudicially as spectators according to gender.

McCall demurs from the anxious assumptions about the visual that underlie these arguments. First, the sense that we are “in the picture, photographed by its light” is here met with interest, not dread. Then, too, even as his projections are scaled to the body, they hardly discipline it: on the contrary, they invite its participation. Finally, even as the films play with our discrepancies as figures, they do not fix on our differences: again, on the contrary, viewers become partners not only to each piece but to one another. In some ways McCall returns us to the benevolent phenomenology of Merleau-Ponty, for whom we are positioned, first and foremost, as bodies among fellow bodies in “the flesh of the world,” not as images to be screened for the volatile (dis)identification of others. The films thus suggest an aesthetic of “symmetries and repetitions and doublings” based on common properties of our shared corporeality, which in turn suggests an ethics of intimacy and reciprocity rather than one of alienation and aggression.19

Breath, 2004. Digital projection. Hangar Bicocca, Milan, 2009. Photo © Giulio Buono.

If the horizontal pieces redouble the usual orientation of both seeing and cinema, the reference to vision and film is less insistent in vertical pieces such as Breath I–III, Meeting You Halfway, and Coupling (all of which deploy one projector), yet the engagement of the body might be more profound as a result. Indeed, the three Breath pieces evoke a lung inhaling and exhaling, an evocation of the body less as an image than as an organism. McCall points to corporeal associations in his terminology for the vertical pieces, too—not only “footprint” for the patterns traced on the floor, but also “membrane” for the surfaces of light and “standing figure” for the volumes that they describe.20 At the same time they produce strong architectural resonances as well: McCall sometimes refers to the vertical shapes as “chambers,” and even as they open and close before us, we tend to stand distinctly inside or outside them at any given point in time.21 This architectural connection is deepened by the large spaces necessary to stage the films, the vertical ones in particular (which are sometimes shown in industrial structures converted into galleries).

Breath III, 2005. Digital projection. Hangar Bicocca, Milan, 2009. Photo © Giulio Buono.

The cycle of the vertical projections varies between fifteen and thirty-two minutes. Breath (2004) consists of an ellipse that expands and contracts as a wave travels through it, producing openings and closings in the figure as it does so. Breath II (2004) puts two traveling waves into action, at different speeds, as the ellipse around them expands and contracts, and this interaction produces even more apertures and closures (some of which appear, if one is inside the figure, as sudden dead-ends). In Breath III (2005) the breathing ellipse is inside the traveling wave, and their mobile configuration is more open as a result. As the title suggests, Meeting You Halfway (2009), which consists of partial ellipses that face each other, performs an encounter between two figures. In the first half of the cycle both contract slowly and then expand rapidly (though they do so at different speeds), whereas in the second half one ellipse follows this pattern while the other does the reverse. The movement is mostly vertical; the slight horizontal motion comes from a floating wipe that moves back and forth across the two forms, revealing more of the one while covering more of the other.22 As usual with McCall, this scheme sounds logical as far as figure and rhythm go; it is the protean volumes that draw our attention. Finally, Coupling (2009) explores a new form, which the artist calls a “circle wave.” When a violin string is bowed or plucked, a wave moves with different amplitudes between the fret and the bridge, producing the sounds we hear; if we imagine this line, complete with undulations, as a circle, then we have a circle wave. In Coupling two circle waves appear, one inside the other. The undulations not only distort both circles but also, at different times in the cycle, break the circles at opposite points, thus creating two openings, one to the exterior of the projection, the other in its interior.

Sequential frames of Breath III, 2005.

Meeting You Halfway, 2009. Digital projection. Hangar Bicocca, Milan, 2009. Photo © Giulio Buono.

This account only begins to describe the footprints of these pieces. As for the volumes, they have to be experienced in situ; as with recent shapes devised by Serra, they cannot be anticipated or recalled with much accuracy. The projections thus slow and thicken space in ways that make the ambiance more substantial and the viewer more responsive than usual; at the same time the complexity of the figures poses a challenge to perception and cognition alike. Again as with recent pieces by Serra, they are hard to learn, perhaps impossible to know, and this might prompt two different thoughts: on the one hand, we might reflect on the difficulty of our everyday negotiations of space, actual and virtual; on the other, we might trust all the more in our experience and intuition in this navigation, whereby these mapping skills are affirmed.23 Yet not all is benign here: there remains the dark, which is the medium of the projections as much as the light is. It supports the films, but it also surrounds us, and it has primordial associations that cannot be bracketed entirely.24

At the same time, inside the vertical projections in particular, one is bathed in a pale, silvery light. This experience might evoke legendary encounters with celestial luminosity, some pagan, some Christian. On the pagan side, there is the mortal Danae impregnated by Zeus with golden rain, as pictured by Titian, say, or the mortal Endymion bathed in the light of his lover Selene, the moon, as pictured by Girodet. On the Christian side, there is the Annunciation of the Virgin, or the ecstatic communion of Saint Teresa with God, both of which are usually figured as rays of heavenly light bestowed on mortals below. This spiritual dimension is difficult for a materialist like McCall to discuss—“bodies and interactions and exchange are not divine ideas,” he has stated simply—but he does not deny that it exists.25 Yet secular associations are salient here, too, such as the tendency of life forms to bend toward the light of the sky. An even more worldly connection is to the light of stage spots, which underscores once more how the projections are also performances in which we figure.

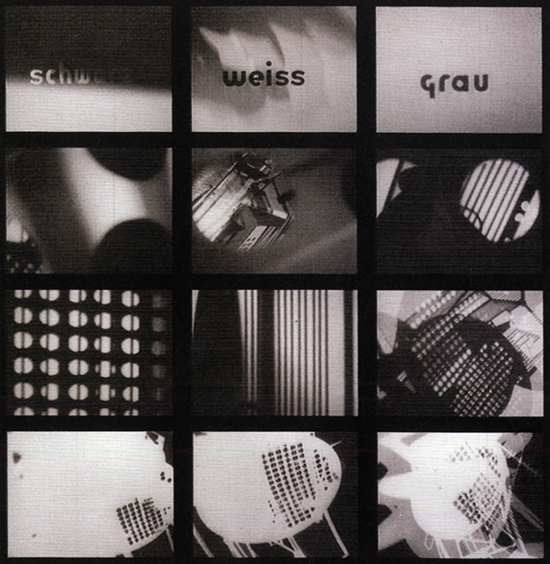

Although the solid-light films emerged in the double context of structural film and site-specific installation of the early 1970s, they also look to a key moment in the historical avant-garde moment, the light experiments of László Moholy-Nagy in the 1920s and 1930s. Moholy based his mature practice on this fundamental question: Can mediums associated with indirect reproduction—that is, of a musical performance in a recording, or of worldly appearance in a photograph, or of a dramatic story in a film—be opened to direct production—that is, to the active making of sound, light, or motion? In this modernist quest Moholy took, as his privileged mediums, the photograph and the film, which he understood almost etymologically as a matter of light written on a support. According to Moholy, this new technology of filmic transparency was certain to transform other mediums, and already in Painting, Photography, Film (1925) he proposed a re-mapping of the visual arts into an “entire field of optical expression.”26 It is this famous thesis of a “new vision” that Moholy elaborated in From Material to Architecture (1929; published in English in 1932 as The New Vision), which redefined painting as “material,” sculpture as “volume,” and architecture as “space,” and posited a necessary passage from the first condition to the last—“from material to space.” In short, transposed from photography and film, transparency was to become a “new medium of spatial relationship” in general.27 Moholy went on to explore this radical dematerialization, especially in his Light Prop for an Electric Stage (1930) and other “light-plays,” but his work was cut short by wartime exile and premature death.

Coupling, 2009 (in foreground). Digital projection. Hangar Bicocca, Milan, 2009. Photo © Giulio Buono.

In his neo-avant-garde moment of the early 1970s, McCall effectively recovered this truncated avant-garde project: his films also pass through the screen of reproduction to the reality of production, and they also move “from material to space” via “light-plays.” Yet in doing so McCall reversed the Hegelian emphasis in Moholy on the progressive sublimation of the arts, and regrounded his exploration of vision and space in the given materiality of our bodies and our architectures.28 Whereas dematerialization was a dream for modernists like Moholy, it has became a default for many artists lately: in much installation involving film and video projection, a virtualizing of bodies and architectures seems all but automatic.29 Here again McCall makes an important intervention with his insistence on embodiment and emplacement: the experience of his solid-light films, early and recent, is one that, though immersive and intense, is not sublime or schizoid; it is also one that, though private and contemplative, is social and interactive.30 To play with light effects is often to abandon (or at least to occlude) space in favor of image or illusion. This is not the case with McCall: as with Serra, a mobile viewer, who is also perceptually and cognitively alert, stands in counterpoint to the stunned or arrested subject of spectacle, which is also private or at least nonsocial in a way that the solid-light films are not. At least for the duration of his films McCall diverts these aspects of spectacle to other ends, and these qualities give his work a renewed relevance and a redoubled criticality.

László Moholy-Nagy, Light-play: Black/White/Gray, 1930. Frames from 16 mm black and white film (5 ½ minutes). Courtesy of Hattula Moholy-Nagy.