CHAPTER 10

GROUP RITUALS

Large stable populations such as those that came together on the Great Plains may develop a collective approach to the management of spiritual power, one in which a number of people work together to obtain, renew, and apply the power, and train and certify novices in religious matters. This group work is an alternative to healing or spiritual teaching performed one-on-one as each single case arises. Instead there is coordination of all interested parties, who meet regularly, according to a seasonal calendar. Their continual activity is considered beneficial to the entire tribe, for it may anticipate and prevent general misfortune and illness, or reestablish the proper workings of the universe, and the whole community comes to rely on it. The presence of a group approach to spirituality does not totally eliminate the activity of individual power seekers, or curers and their patients; individual, dyadic, and group patterns coexist in most societies. Thus, when proposing the “individual” (vision quester) and “shamanic” (medicine man-patient) cult institutions, anthropologist Anthony Wallace also identified the group approach as a next evolutionary step, and termed it “communal” cult institution.

Communal approaches to the spirit world are most easily examined through public rituals. Public rituals often involved nearly all tribe members at once as participants or spectators. On the Plains there were a number of these ceremonies, some specific to single tribes, others diffused through nearly all of the tribes. They present a wonderful opportunity to see, hear, and feel the expression of a community’s deepest values, and group rituals have been studied extensively by non-Indians seeking cultural knowledge. Revealed are the common elements of Indian religion and the particulars of tribal world-views. Along the way, the historical, social, and philosophical connections between different groups are often illuminated.

Some care is necessary when focusing on large-scale rituals; in the past, expositions of Native religion have done so to the detriment of full understanding. A false impression can be created, that people went to a few big ceremonies every year that totally satisfied their needs. But the large ceremonies were really points in a continual round of ritual activity. They meshed with each other and with less public and spectacular religious observances, and it was the entirety of this activity that was most important. From a Native viewpoint, a ritual might not be considered predominant simply because it was large. With these cautions in place, we can look at a number of public rituals that were, and are, characteristic of Plains religion.

THE MASSAUM

A bustling mass of dancers in fantastic animal spirit costumes characterized perhaps the earliest of the known Plains group rituals, the Cheyenne Massaum (“Crazy Lodge”). Properly speaking, the Massaum was a ceremony of the Tsistsistas, the larger of two known ethnic units that became the historical Cheyennes. Tsistsistas spirit impersonators convened at midsummer, as the blue star Rigel was about to rise in the southeast early morning sky, for a five-day rite. At stake was nothing less than the renewal of the Tsistsistas/Cheyenne world. The dancers reenacted the creation of the universe as recorded in myth, recharged the animal-based spiritual power that protected and guided them through the year, and restored their mastery of hunting, essential to their survival as Plains people.

The ritual itself was enormously complicated. The ceremony first had to be pledged by a woman, who upon completing it would function as instructor to women pledging in subsequent years. The pledging woman recruited three other women, who were former pledge makers, and a man to serve as both instructors and the main performers. The new pledge maker assumed the role of Ehyophstah (Yellow-Haired Girl), daughter of the thunder and earth spirits, and her fellow instructors represented other spirits described in myth. The pledge maker also decided upon a location for the ritual, most likely in consultation with a council of ceremonial leaders. Messages were sent to the dispersed bands to gather in the latter part of July at the chosen site. The camp was always oriented toward Bear Butte, near present Sturgis, South Dakota, which the Cheyennes considered their sacred mountain. After they assembled the camp, the participants prepared for the ritual by purifying themselves in the sweat lodge. The main instructors and their assistants were painted red to transform them into spiritual actors.

During each of the next five days there were four or six main thematic activities, as summarized in Table 10.1. Each theme was developed through some combination of sacred procedures including prayer, song cycles, body painting, sand painting (creating images on the ground in colored sand), fasting, sign language performances, the smoking of tobacco with ancient-style straight bone pipes, and dancing. During the first day, a lodge was constructed which represented the universe before creation. Then this universe was inhabited by the five instructors/spirit impersonators. The Yellow-Haired Girl assumed a central role as the mythic teacher of the hunt. Next, the wolf spirits were brought alive as the master hunters, to exemplify the relation between predator and prey that order the natural world. The leaders of the wolves were Red Wolf and White Wolf, corresponding to the red star Aldebran and white star Sirius, whose appearances exactly framed, 28 days before and after, that of the blue star Rigel.

As a world renewal ceremony, the Massaum had much in common with rites held by tribes across the continent, from the Yuroks of California to the Algonquian Munsi and Mahicans of the East Coast. Given the Cheyenne’s own background, the Massaum is seen as an outgrowth of ancient Algonquian ritualism. In turn, the Algonquian tradition has a great deal in common with Siberian shamanism. Anthropologist Karl Schlesier defined 134 traits comprised by the Massaum ceremony and was able to correlate 108 of these with shamanic practices in Siberia (Schlesier 1987). While some of the resemblances were of a very general kind that one would expect to find across any number of religions, such as the idea that the Supreme Being lives in the uppermost sky, others were quite specific, such as the sacrifice of albino animals and the making of seven marks on a ceremonial tree. Schlesier, therefore, made a case for the great ancientness, consistency, and durability of Cheyenne religious ideas as expressed in the Massaum.

TABLE 10.1 Main Ritual Activities of the Massaum

| FIRST DAY | SECOND DAY | THIRD DAY | FOURTH DAY | FIFTH DAY |

| Sacred tree selected, cut down, and erected at ritual site | Four small mounds and directional lines added to lodge floor | Smoking and body painting symbolize the giving of Ehyophstah to the people | A second, interior camp circle is made, representing the abode of the animals | In the dark of early morning the five main performers paint themselves and prepare to emerge |

| Rafters set around central tree to form lodge | Male instructor paints sun and moon sign on lodge | The wolf skins are stuffed and painted, ritually enlivening these master hunters | In the animal abode participants prepare to reemerge as animals, with pairs of walking sticks representing animal forelegs | The five spirit impersonators come out to watch for the appearance of the star Rigel, which signals the start of a ceremonial hunt |

| Earth floor of lodge smoothed | Seating arrangement of main participants in lodge is established | At noon dog meat plus three types of plant food are served in a ritual meal | A crescent shaped shade is erected across from the lodge, representing a hunting pound | Many costumed animal impersonators emerge and a hunt is mimicked; the hunt is repeated four times |

| Fireplace constructed on east side of tree | Wolf and fox skins brought into lodge; more participants enter | At nightfall sacred songs are taught | The first animal impersonators, wolves, emerge from the lodge and are viewed by the public | Fractions of sacred meat are distributed to all in the camp to symbolize the outcome of the hunt |

| The wolf impersonators move through the camp, making it a sacred universe | Led by Coyote, the animals process to a stream to drink, ending their fast | |||

| At nightfall sacred songs are taught | Main performers return to the lodge and ritually disassemble the interior, ending the ceremony |

Source: Schlesier (1987).

Though they considered it fundamental, the Cheyennes could only stage the Massaum intermittently during the years of white intrusion into their territory, and they last performed it in an abbreviated ceremony in 1927. Reconstruction of the ritual and its underlying ideology at this late date is still important, not only for understanding the Cheyennes, but also because the Massaum contains many symbolic elements that reappear in other Plains group rituals, including the Sun Dance.

THE OKIPA

Another world renewal ritual that prefigures the Plains Sun Dance was the Okipa ceremony of the Mandans. The Okipa was also probably an influence on the Massaum, for the Cheyennes became acquainted with Mandan culture as they moved onto the High Plains, although the two rites are ultimately different in detail. A lively and sometimes lurid description of the Okipa, illustrated with four detailed oil paintings, was delivered by frontier artist George Catlin after his 1832 visit to the Mandan village near present-day Bismarck, North Dakota. Catlin was one of only a few non-Indians to witness a complete Okipa ceremony. Five years later the tribe was nearly wiped out by smallpox, and though the ceremony was continued until the 1880s, the later versions were diluted, and Catlin’s account remains important.

The Okipa was a summer ceremony staged over four days. In general, the rite involved dancing, feasting, fasting, body painting, the giving away of presents, and physical ordeal. These activities took place inside a ceremonial earth lodge and also outside, in an adjacent village plaza marked with a central cedar pole. The lead ritualist was an impersonator of the primordial figure Nu-mohk-muck-a-nuh or Lone Man (First Man, Only Man). Lone Man was joined by other spiritual figures from creation myth to enact several vignettes illustrating the origins of the tribe and the restoration of spiritual power as derived from animals. In one segment, Lone Man chased away The Foolish One, a clown painted black with charcoal and bear grease, who pestered women with a large wooden phallus. This episode represented the establishment of an orderly society. Also enacted by costumed participants was a sacred release of imprisoned animals, which functioned, like the hunt segment of the Massaum, to signify the origin and continuance of the hunter’s way of life. The release of captive animals for human use is a nearly universal mythic theme on the Plains (see Chapter 3). According to Mandan belief, the actual release occurred at Dogden Butte, a glacial ridge about 60 miles north of present-day Bismarck. Men wearing full buffalo skins performed the Bull Dance in the plaza to summon the bison for human consumption.

FIGURE 10.1 The Last Race, Mandan O-Kee-pa Ceremony, by George Catlin, 1832.

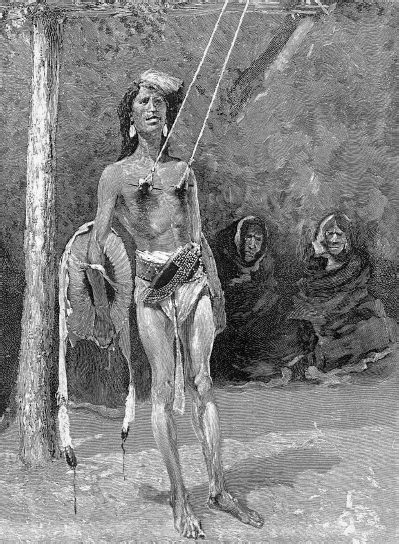

The most sensational part of the Okipa was the ordeal that Catlin called the “cutting scene.” Young male fasters submitted to having their chest or backs pierced in two places to accept splints. Supplicants were expected to suppress any show of pain when being pierced. Rawhide ropes were then tied to the skewers, and the men hoisted toward the rafters of the lodge. They remained suspended for many minutes until the pain caused them to pass out. Once they appeared dead, they were lowered to the ground and left alone until they came to. While unconscious, the men might have revelatory visions, and their revival symbolized a spiritual rebirth. Upon reviving, some men made even a greater sacrifice by having fingers chopped off. The small and index fingers of the left hand were amputated, leaving those most necessary for drawing a bow.

The Massaum and Okipa were unusual in their reliance on masked dancers, since masking and spirit impersonation were not prevalent on the Plains, even though these are common ritual devices in many parts of the world, including most of the adjacent North American culture areas. Otherwise, however, the Massaum and Okipa were typical, if not prototypical, of Plains communal ceremony. In this regard they can be considered along with other group rituals for the harnessing of medicine power, the initiating of new adepts, and the renewal of harmonious relations between humans and the spirits, including the rituals of the Omaha Shell and Pebble societies and the Crow Tobacco Society, as described in Chapter 4.

MEDICINE BUNDLE RENEWALS

Closely associated with the other organized rituals were the traditions, in many tribes, of renewing medicine bundles. Medicine bundle traditions span the realms of individual and group ritual; some bundles contained the personal medicine of a single owner, while others were thought to affect the destiny of the entire tribe. Bundle ceremonies might be staged by individuals with a few assistants in a relatively inconspicuous way that belied their importance, or included in the program of a large, multiday tribal ritual.

Simply defined, a medicine bundle is a set of objects kept in a wrapping of animal skin. The typical objects are stones, chunks of mineral paint, feathers, bird and small mammal skins, sprigs of sage or other herbs, and scalps. Sometimes pipes or arrows may be included. In a few cases, notably among the Kiowas, the main object is a simple male or female doll representing a primordial human. This collection of items functions as a repository and source of spiritual power and has its origin in one or more visions of an individual person or else in a tribally circulated body of myths; in either case, the underlying story includes directions for the ritual use and care of the items. The power of the bundle is often specific, the most common purposes being success in warfare, hunting, gardening, curing, or love. Depending on the guiding principles, a bundle and thus its power might be transferable from one owner to another through purchase or direct inheritance, or, in the case of tribally significant bundles, as a matter of public appointment, for instance, the tribal council might appoint a keeper from among members of an eligible family.

The bundle became a focus for ritual because it was supposed to be renewed at regular intervals. The skin was unwrapped and the items inside were examined and contemplated. The owner meditated on their origins and meanings. He smoked them in sweet grass or cedar incense as a blessing, prayed over them, and handled them in formal ways, for example, keeping them from touching the ground, as a show of reverence. Items might be cleaned, repaired, or repainted. The bundle renewal was the occasion for the performance of origin myths, sets of special songs, and dancing.

As a “complex” of tribal religious activity, the bundle tradition reached its most complicated development among the Mandans and Pawnees. While these tribes’ bundle practices have faded from existence, there is abundant ethnohistorical information about them. The Mandans had a system of bundles that affected all aspects of tribal life. There were personal bundles, tribal bundles, and bundles that were subsidiary or auxiliary to the tribal bundles. Particular bundle ceremonies ensured the success of every important tribal enterprise, from fish and eagle trapping to buffalo hunting to garden fertility, warfare, and health. Rights to particular bundles were controlled by clans, and the ownership of bundle rights through inheritance or purchase was a prerequisite for anyone wanting a leadership position in the tribe.

The Pawnees had a similar complicated, ranked system involving both personal and tribal bundles. The higher-order Pawnee bundles were situated in villages rather than clans; they were inherited and owned by the village chiefs, though handled by a separate class of priests. A set of five Pawnee bundles superseded all others, four of which stood for the four semi-cardinal directions, and the last, the evening star (Venus shining brightly soon after sunset, called “female white star” in Pawnee). These five federation bundles, with the evening star bundle preeminent, integrated the various Pawnee villages and the cosmological world simultaneously and were tended by priests at the top of the religious hierarchy. They had to be renewed every year at the time when the first thunder of spring was heard, around the time of the spring equinox and appearance of the evening star. Priests of the Skidi band of Pawnees kept a large oval hide map of the night sky showing the position of numerous stars, which may have been used to schedule ceremonies or simply to illustrate the celestial myths reenacted through bundle rituals.

Anthropologist Jeffrey Hanson (1980) observed that the complexity of Plains bundle traditions mirrors organizational complexity, which in turn corresponds to ecological conditions and subsistence practice: semisedentary horticulturalists with more complicated forms of social and political organization had the more intricate and specialized bundle systems.

The Skidi Pawnee Morning Star Ceremony

The Pawnee bundle traditions correlated with the only example of human sacrifice on the Plains and one of only a few to ever develop among the North American tribes. Just as Pawnee rites associated with the spring equinox were marked by the appearance of the evening star, those celebrating the late April season of approaching warm weather were indicated by the morning star (Venus or possibly sometimes another planet, shining before dawn, conceived of as a male warrior) in conjunction with the moon and near the constellation Aries. The morning star ritual, not strictly required every year but held upon a sponsor’s dream (which seems to have anticipated the required celestial alignments), involved the slaying of a captive to appease the mythic beings and ensure health, plentiful food, and success in battle.

Details of the sacrifice procedure and the sequence of steps differ among accounts and probably varied over time; following is a sample compilation. In the fall prior, the dreamer and some supporters went on a highly ritualized raid to obtain a girl captive about age 13 (or sometimes a boy) specifically for the rite. Not knowing her approaching fate, the captive was well treated while the time of sacrifice approached. When the morning star’s appearance was imminent, the captive was honored over a three-day period with feasting and finery, and then anointed with sacred paint, with her body made half red and half black. Special songs described every step.

After midnight starting the fourth day, the captive was led to a scaffold of poles and tied to face the rising planet. In quick succession, executioners dashed from out of hiding around the scaffold and delivered the deathblows. One made a pantomime of torture by fire, singing the girl’s groin and armpits. The next shot her once with an arrow in the heart, and a third delivered a blow with a club. A priest then cut out the victim’s heart or at least made a chest incision allowing the free flow of blood. The priest marked his face with the blood, and blood was supposed to drip on an offering of buffalo meat set up under the scaffold. Next, every man and boy of the tribe emerged and fired an arrow into the back of the corpse to participate in the sacrifice and tap into the good fortune that was believed to result.

The sacrifice coincided with the renewal of the morning star bundle. Both during the planning of the dreamer’s raid and as the captive was prepared for execution, the bundle was opened to reveal its contents—otter, hawk, and wildcat skins, feathers, scalps, tobacco, paint, a pipe, an arrow, two ears of sacred corn, and so on—and these items were prayed over and blessed with smoke. Some accounts indicate that the captor and executing priest wore some of the bundle items as they fulfilled their duties, that the captive was fed with a little bowl and spoon from the bundle, and that the fatal arrow was taken from the bundle and then returned.

The symbolism referred to fertility. One interpretation is that the executioner’s arrow represented the act of planting. Another says that the arrow referred to hunting prosperity, and that women hacked the corpse with their hoes to similarly consecrate the gardening implements. Regardless, ultimately the procedure was a reenactment of creation myth. The peculiar means of injury were allusions to episodes in the Pawnee origin story. Even the scaffold embodied mythic ideas, in that it was built from different wood species representing powerful animal spirits and their associated cardinal directions. The victim’s role was that of evening star, whose death reunited her with morning star, personified by her captor and executioners, to begin life anew and ensure the return of the buffalos and the growth of crops.

The morning star sacrifice is known from instances in the early 1800s and presumably dated deep into the past. Only the Skidi band of Pawnees held the morning star sacrifice, although there is some indication that the related Arikaras of the Upper Missouri also had a sacrificial rite in earlier days. Other Pawnee bands rejected the idea of human sacrifice, at least during the Historic Period. White traders and agents who entered Pawnee territory abhorred and opposed it, and under their influence the Skidis lost their commitment to the sacrifice element. In 1816, the leader Lachelesharo (Knife Chief, Old Knife) and his handsome son Petalesharo (Pitarésharu, “chief of men,” Man Chief) spoke out against the execution of a Comanche captive. Others in the tribe insisted that the sacrifice was needed to ensure prosperity. The daring Petalesharo cut the girl down at the last moment and rode off with her to send her home. The episode became legendary, and when Petalesharo visited Washington and other eastern cities in 1821 with a chiefs’ delegation, he was feted and given a silver medal for the deed. The last known Skidi human sacrifice was made with an Oglala girl named Haxti on April 22, 1838. Afterward and into the twentieth century, the Skidis continued to renew the morning star bundle on the celestially determined dates, but without human sacrifices.

The early Plains Indian authority Clark Wissler supposed that Pawnee human sacrifice evinced influence from the Aztecs of central Mexico, since astronomy and sacrifice (including scaffold execution) were key features in the religion of the Aztec Empire circa A.D. 1500. And as Caddoans, the Pawnees shared in a general cultural heritage from the Southeast United States, where ritual cannibalism and the prehistoric presence of temple mounds and complex societies might also suggest ties to Mesoamerica. Later scholars have been more cautious in discussing such connections, however, citing the current dearth of archaeological evidence for contacts between the Aztecs and Indians of the Southeast or Plains.

Sacred Arrow and Pipe Ceremonies

Some of the most notable medicine bundles contained sacred arrows or pipes as their principle objects. (Rituals in which sacred pipes are renewed should be distinguished from the calumet or “peace pipe” ceremony, in which a pipe is passed around and smoked to call blessings on visitors or cement agreements between groups. The calumet ceremony is treated in Chapter 11.) The Arapahos kept a single flat pipe in a special tipi, always suspended off the ground, its proper care ensuring the prosperity of the entire tribe. The Blackfoots had 17 sacred pipe bundles distributed among tribe members and similarly venerated. Seven pipes were considered essential to the well-being of the Poncas. Each pipe stood for the particular powers and ritual responsibilities of one of the Ponca clans; six were kept together in one bundle to represent tribal unity, and the seventh was maintained separately by the chief’s clan and used in chiefly matters such as the safeguarding of buffalo hunts and cursing of criminals.

The Cheyenne Sacred Arrows were bestowed on the tribe by Sweet Medicine, the culture hero and trickster figure. Sweet Medicine appears in Cheyenne myth as a young boy with amazing knowledge and powers who can shift shapes and assume the form of many animals. In some accounts it is said that he lived among the tribe for several generations. In one key episode, Sweet Medicine and his wife discover a mysterious hidden chamber within a mountain in the Black Hills, identified with Bear Butte northeast of Sturgis, South Dakota. There they find two sets of four arrows attended by sacred beings; the beings invite them to take one set, which is wrapped in coyote and buffalo skins, and instruct them in its meaning and care. Sweet Medicine and his wife emerged after four years within this holy lodge, and they passed the Arrows and sacred knowledge on to a succession of virtuous men—the Arrow Keepers—through the generations.

The Cheyenne Sacred Arrow renewal ceremony was pledged by an individual, and the scattered tribe members were summoned to gather for it at an appointed place, much as in other group rituals. Within the camp circle, a giant tipi reminiscent of the mystic mountain lodge was set up to contain the arrows. Over a four-day period the Arrows, and thus tribal fortunes, were restored through a series of procedures. The campers brought forth offerings of tobacco or valuables and laid them before the Arrow bundle by an altar in the tipi. Medicine men received the bundle from the Arrow Keeper, respectfully opened it, and repaired the feathers and sinew of the arrows. They blessed a large number of willow sticks representing each family in the tribe by passing them through smoke at the altar. The Arrows were placed temporarily in alignments signifying the directions of the cosmos and paired to stand for the complementary relationship between buffalos and humans. All the men of camp came through to witness the Arrows in their refreshed state before they were re-bundled and returned to the Arrow Keeper. The main participants sung four closing songs said to have been taught by Sweet Medicine, purified themselves in a sweat lodge, and the ceremony was closed; another year of tribal prosperity was assured. Versions of the Sacred Arrow renewal rite are still conducted among the Southern Cheyennes in Oklahoma, where the Arrows are now kept, and Northern Cheyennes may participate there or, infrequently, host the Arrows for renewal at their Montana reservation.

Arval Looking Horse, a Lakota Sioux, became the keeper of his people’s Sacred Pipe in 1966, when he was only 12. At that time the prior keeper, his grandmother Lucy Looking Horse, died (women as well as men may keep the Pipe among the Lakotas), and she had had a vision that Arval should be the next in line—representing the nineteenth generation. Arval understood the origin of the Pipe from the following story. Long ago a man (implicitly a Cheyenne) was out scouting and he came upon the huge rock formation in northeast Wyoming, Mato Tipila (Bear Lodge), now called Devils Tower. It was a sacred mountain, with an entrance on the east, an interior like a tipi, and an exit on the west side. The man went inside, where he found the Sacred Pipe on the north side and a bow and arrows on the south side. He chose the bow and arrows and left with them, and since then the Cheyennes have had their Sacred Arrows. Later, a mysterious radiant woman delivered the Sacred Pipe in a bundle to the Lakotas and taught them how to pray with it and care for it. As she then disappeared over the western horizon, she assumed the shape of four animals, the last being a white buffalo calf. The Pipe is therefore known in Lakota as Ptehincala hu cannunpa, the Buffalo Calf Pipe.

The Buffalo Calf Pipe is considered the center or trunk of pipes, with all others its roots and branches. Its stem is equated with man and the bowl with woman, in a symbolic representation of procreative power. Believers attribute great powers to the Pipe for protecting forthright people or punishing wrongdoers. A story relates that once, when an Indian agent had the Pipe seized and brought to his agency, the Indian policeman involved in the seizure all died, and the agent had to ask the Pipe Keeper to come and take it away. Some also say that the Pipe grows shorter when times are bad, though Looking Horse himself disputes this belief.

Looking Horse keeps the Pipe in a red metal outbuilding in his yard at Green Grass, South Dakota on the Cheyenne River (Sioux) Reservation. Inside, the Pipe bundle is suspended off the ground and kept along with the drum and other ritual implements used in its veneration. Periodically, the Pipe is taken out for renewal. This blessing generally is held once a year, in conjunction with the Sun Dance, though Looking Horse once kept the Pipe put away for seven years, upon instruction from the spirits, who were displeased with people’s bad behavior and lack of respect. When a ceremony is announced, hundreds of people come from far and wide. Numerous medicine men attend to help conduct the ritual and benefit from the blessings.

The ceremony for the Sioux Sacred Pipe is much like that for the Cheyenne Arrows. For presenting the Pipe, a square altar area is outlined on the ground near the outbuilding with stones (as a more permanent rendition of the traditional outline made with small tobacco bundles) and four cottonwood saplings decorated with flags in six colors that represent the four cardinal directions plus earth and sky. Worshippers, having first purified themselves in a sweat lodge, process to the altar barefoot and bearing sage. Singers drum and sing special songs. The Pipe is brought forth from its lodge, removed from the bundle, and placed on a tripod set up at the center of the altar area for all to see. People reverently approach the Pipe, pray to it, and touch it; some are overcome with emotion in its sacred presence. They may bring offerings in fulfillment of vows, or their own personal pipes to absorb the sacred power of the Buffalo Calf Pipe. To conclude the ceremony, all those with pipes at once fill them with kinnikinick, light them, and offer them to the six directions. Then the Pipe bundle is put away in its shed and the worshippers retire for a feast of buffalo meat, fry bread, and other Indian foods.

THE SUN DANCE

Of all the large-scale rituals on the Plains, the Sun Dance is the one that is most widespread and which has lasted the longest in the period of recorded history. Twenty tribes practiced it at the peak of the horse-and-buffalo economy in the early to mid-1800s, and many continue today. It is also the ritual that has gotten the most attention from non-Indian onlookers and writers. For these reasons, the Sun Dance has become iconic of Plains Indian life for many people. In one way at least, the Sun Dance is indeed very typical of the culture area, for like other aspects of Plains culture it is at once quite uniform over time and space, and yet takes on specific details and meanings in each tribe where it is found.

The term “Sun Dance” was coined by early non-Indian observers who seized on the Sioux dancers’ custom of staring at the sun. This generic term is now in use even among Indian people when speaking English. But though the ceremony includes acknowledgment of the sun’s power through ritual and symbol, it is not about sun worship.

The original tribal names better suggest Native perceptions of the ceremony. For many groups, the salient feature was the making of a special ritual lodge, and names among the Kiowas, Assiniboines, Crows, and others simply alluded to the lodge or some part of its structure. It may be that at least some of these names were metaphoric references likening the lodge construction to the assembling of the tribe. The Cheyennes recognized the idea of earth renewal, calling the ceremony New Life Lodge. A reference to sacrifice is found in the Arapaho name Offerings Lodge, and the Blackfoot term Medicine Lodge indicated power acquisition. The title Thirsting Dance among the Utes, Shoshones, Crees, and Ojibwas notes the dancers’ practice of forsaking food and water. The Tetons and Poncas called it Sun-gazing Dance on account of the staring custom.

Behind these variable names and the general theme of renewal were different emphases. While the Cheyennes thought of the dance as a means of rekindling life, the Crows held the dance to vow revenge against a relative killed by tribal enemies through the agency of a sacred doll. In what amounted to a reversal of the Crow rationale, the Kiowas staged the dance ostensibly to honor their tribal medicine doll, though the doll veneration was in turn a means of forecasting revenge and putting the world right. The main purpose of the Blackfoot version was to renew and transfer ownership of medicine bundles. Whatever the most explicit reason, the Sun Dance was a complete pageant, a gathering for survival and social purposes and the public expression of religious ideas.

The great gathering was made possible by the abundance of summer buffalo, and in turn the ceremony was a way of coordinating a maximally effective summer hunt. Bands that had been dispersed during the cooler weather met at an appointed place in June and joined in chasing the amassed herds. Large numbers of animals were slain and the meat was processed to feed the crowd and set up a surplus for later in the year.

Usually the bands camped around a huge circle, with each band’s position on the circle indicating its status in the tribe or the point in past time when it originated. The gathering restored a sense of community across the entire tribe. Old family ties between siblings who had been scattered through marriage were renewed, and new friendships were made. The men’s military associations that drew members from multiple bands were formed during this time of year, and they were pressed into service as police for crowd control—to make sure the hunt was run fairly and to curb rowdiness in camp. There was a festival atmosphere about the camp, with storytelling, gambling, horse races, feasting, secular singing and dancing, and an air of romance. It was the perfect time for courtship. The Lakotas have a saying: “Children are born nine months after the Sun Dance.”

The religious ritual itself, unfolding over a week’s time, loomed over all of this fertility and family life as if to sanctify it. In general the Sun Dance resembled, and grew out of, earlier large Plains earth renewal ceremonies such as the Massaum and Okipa, and was probably influenced as well by other rituals for calling game, healing, and initiating medicine men. It appears as a type of ceremony distinguishable from the others, and spreading through the Plains, after about 1800. There was great variability in the details, but a common description is possible. Like many Plains ceremonies, the Sun Dance was an annual event in principle, though sometimes, depending on local circumstances or tribal habit, one or more years could pass without one. The vision or vow of a male or female sponsor initiated preparations. In coordination with this inspiration, a medicine man was identified as leader, his assistants gathered, and individual dancers vowed to dance to fulfill some personal purpose. Men were the principal dancers and singers in all tribes, with some tribes including women in these roles also.

The dancers readied their regalia and sought elders to instruct them in the proper ways of dancing. Depending on the tribe, some ritual allusion to hunting was made; either the worshippers collected buffalo tongues, or they held a special hunt, or obtained a buffalo hide to be displayed in the ceremony. A place for the lodge had to be determined. A tree that would become the center pole of the lodge was found through an elaborate sequence. The tree might be revealed in a vision, and scouted and captured like an enemy, with multiple feints of attack. Often, virtuous women were selected to carry out some of these preliminary steps. More highly formalized activities followed: setting up and decorating the center pole with a buffalo effigy or thunderbird’s nest, clearing the ground around it, building a circular lodge with rafters radiating from the pole and with a shade arbor around the edge, and making some kind of altar with earth, buffalo skulls, and other symbolic elements.

Dancers then occupied the lodge and began dancing to special songs. Men would be bare-chested, barefoot, and garbed only in a calf-length kilt of skin or cloth, perhaps with armlets and eagle plumes or a sage wreath worn on the head. More sprigs of sage were stuck in the dancers’ waistbands. Cheyenne and Arapaho men added intricate painted designs on their chests, backs, and arms. Women wore special dresses and robes and sage wreaths too. The dance itself involved bobbing in place while focusing one’s eyes on the top of the sacred pole. The dancer held between his lips a whistle made from the hollow wing bone of an eagle, which he sounded frequently to proclaim the intensity of his devotion. All during the event, dancers fasted. The leader’s assistant might come before them with a paunch of water and callously splash it on the ground to test their determination. This very physical means of meditation was stopped from time to time so the dancer could rest, fix or modify his regalia and face paint, and perhaps drink a little chokecherry soup, just enough to keep going some more. Through this almost continuous dancing and concentration, it was believed, one became open to acquiring spiritual power.

In some tribes, however, some participants chose even harsher ordeals in order to make even more intense bids for power. The Oglalas, Canadian Sioux, and Poncas in particular emphasized these practices, which have often been referred to in written accounts as “self-torture.” (On the other hand, the Kiowas disavowed injury in the Sun Dance, believing that bloodshed spoiled the mood of holiness.) Dancers and spectators alike might make flesh offerings by having half-inch bits of tissue cut from their arms by the dance leader or his assistant. At this time also, mothers who had vowed to see one of their children through some winter illness brought them forward to have their ears pierced, to fulfill the vow and unify the child’s fortunes with those of the other sacrificers.

In particular, ear piercing made a symbolic bond between the child and those choosing the most dramatic form of ordeal: at the ceremony’s climax, male dancers might have wooden skewers inserted through their breasts to accept tethers that tied them to the center pole. During the piercing and afterwards, the supplicants were not supposed to show any distress over the pain. They leaned backward while dancing to place their weight against the ropes and sought eventually to break free by ripping their flesh, the release signifying ultimate achievement of their vow or bid for power. If the flesh did not give way after some time, supporters pushed the supplicant back or threw robes on them to add weight. Or, the dancer would move to the center pole, lay his head against it in a moment of prayerful resolve, and then dash backward as hard as he could to break loose.

An alternate method was to pierce the back below the shoulders as well as the breasts and hang from four poles about a foot off the ground until the flesh gave way. Or else only the back was pierced and the ropes were tied to one or more buffalo skulls. The supplicant dragged this heavy mass around the circle of the lodge, hoping to break free as the skulls tangled and their horns were caught in the dirt. If he had trouble breaking loose, a child might be sent out to sit on the skulls.

The dancing segment of the ceremony would last three or four days, from dawn to dark. Its end was marked by special closing songs, and for the dancers, it was marked by ritual cleansing in a sweat lodge and release from their fast. The camp dissolved and the Sun Dance lodge was abandoned and left to molder, a last sacrifice to Mother Earth. A tribe’s old Sun Dance lodges marked its territory and stood as mute signposts of time passed. In the pictographic winter counts of the Kiowas, many of the years are actually named for some feature of those year’s Sun Dances (see Chapter 6).

The meanings and teachings of the Sun Dance are rich and complex. When the ritual begins, the celebrants place evergreen sage in the eye and nasal sockets of the ceremonial buffalo skulls to symbolize the buffalos’ coming to life. Other common colors of ceremonial paint and clothing are red for earth, blues for sky, red or white for day, blue or black for night, and yellow for the sun. Every object is invested with meaning. For example, the following explanation was given by the Lakota George Sword circa 1908:

A hoop covered with otter skin ceremoniously is a symbol of the sun and the years. The years are a circle. An armlet of rabbit skin is an emblem of fleetness and of endurance on long journeys and during marches. A cape of otter skin is an emblem of power over land and water. A skirt of red worn by a man is an emblem of holiness. A blue skirt is an emblem of Taku Shanskan, that is, of the heavens, and indicates that the wearer is engaged in a sacred undertaking. Armlets and anklets are emblems of strength and of love and cunning in the chase.

(Walker 1980:182–183)

In Sword’s words one can see how symbols elicit verbal explanations of the tribal belief system that then become learnable to members of the community, especially children. Participants and onlookers see examples of courage, self-sacrifice, endurance, and kinship unfold before them. Coupled with the stark drama of physical endurance and sacrifice, the shapes, sounds, smells, and colors of the Sun Dance contribute to a powerful, tangible enactment of core values.

The Study of Sun Dance Diffusion

In the early years of the twentieth century, anthropologists viewed the Great Plains as a vast natural laboratory for studying questions of cultural development. One of the main issues of interest at the time was diffusion, the process whereby cultural traits pass from one group to another. Anthropologists wondered whether diffusion proceeded in regular ways which could be described in general laws. Some also understood that the presence or absence of diffused traits within a given society would reveal something about that group’s past, and thus that the study of trait distribution was important for reconstructing the history of a region which lacked Native-produced written records. Since the Sun Dance was widely shared across the culture area and was accessible to examination through Indian oral history, non-Indian historical records, and, in some cases still, direct observation, it became an obvious subject for diffusion studies.

Franz Boas (1858–1942), a founding figure of American anthropology, provided the inspiration for the Sun Dance diffusion study. Boas envisioned an approach to the study of cultural traits that was different from that put forth earlier. Prior theorists thought of traits primarily as indicators of a group’s position on a presumed ladder of human cultural evolution. Pottery, for example, indicated that a group had progressed to the level of barbarism, midway in sophistication between savagery and civilization. It is now accepted that the sophistication or complexity of a culture cannot be appreciated only by the presence or absence of a few diagnostic traits, and at any rate, gross categories like savagery and barbarism are not sufficiently helpful to understanding. There was also early speculation of how traits originated and spread, but much of it was fanciful. For example, some theorists proposed that all major technological advances arose in ancient Egypt, a theory that defied the actual evidence. Boas advocated instead for the scientific documentation of traits in their particular tribal contexts. The focus was on understanding the local historical and psychological significance of the traits and their combinations. Part of this inquiry was to determine when a group got a trait, from whom, and how it fit with the other traits that the group already had in a configuration unique to that tribe. Only eventually, after much patient investigation of the particulars, Boas claimed, could general or universal patterns of human development be posited with any confidence. Put another way, before a grand history of cultural evolution could be discerned, a multitude of individual tribal histories had to be recorded. The Boasian program, in contrast to earlier, simplistic forms of diffusionism and cultural evolutionism, became known as historical particularism.

The actual work of this program as it was pursued on the Plains was organized by Clark Wissler of the American Museum of Natural History. Wissler assembled a group effort to study the Sun Dance (and military societies, another subject amenable to diffusionist questions) in many different tribes simultaneously, which would feed a composite picture. Alfred L. Kroeber conducted work on the Arapahos and Gros Ventres, while Robert H. Lowie undertook studies mainly of the Crows, with shorter visits to the Arikaras, Assiniboines, and Shoshones. Leslie Spier made a brief study of the Kiowas. Wissler himself conducted fieldwork with the Blackfoots. Other studies undertaken independently of the American Museum effort were also included in the composite picture, including George A. Dorsey’s reports on the Arapahos, Poncas, and Southern Cheyennes, George Bird Grinnell’s study of the Northern Cheyennes, Alice Fletcher’s work on the Oglalas, and the observations of Lieutenant Hugh L. Scott among the Kiowas.

It was Spier who then gathered the results of these contributing studies and charted the many traits associated with the Sun Dance, recording their presence or absence in 19 tribes, noting how traits were clustered within these tribes, and pairing the various tribes to see the number of traits shared between each pair. By arraying the data in these ways, Spier was able to see patterns in the development and spread of the Sun Dance. His interpretation relied on a concept promoted by Wissler, called the age-area hypothesis, which held that the more widely distributed traits were the older ones, under the supposition that they had been around longer and had more time to spread.

The traits in question included all kinds of details of ritual procedure that could be classified under broader features of the ceremony. For example, several traits had to do with the form of the dance lodge and its components: whether the lodge had a full or partial roof, whether the center pole was decorated with a buffalo hide, whether it was painted, whether there was an altar with buffalo skulls, and whether the altar was excavated. Other traits concerned the actual dancing, such as sun gazing, circling, flesh sacrifices, drumming on hide, and the blessing of spectators, among many others. Still other traits had to do with regalia details, such as the presence or absence of jackrabbit headdresses or white body paint, or whether sage sprigs were worn in the dancers’ belts.

Spier determined that the Algonquian-speaking Arapahos and Cheyennes were at the center of the diffusion of the Sun Dance. These tribes had the highest trait counts—53 and 46, respectively. Not surprisingly, they were at the geographic center of the entire Sun Dance area. The nearby Oglalas had 40 traits, and the Blackfoots and Gros Ventres also had high trait counts, with 37 and 36, respectively. Tribes far from the center had fewer traits, with the Plains Ojibwas and Canadian Sioux possessing only 8 and 5 traits, respectively.

Ultimately the Sun Dance diffusion study was only a partial success. As some of the investigators became preoccupied with patterns of distribution and typicality, Boas’s more basic agenda of recording tribal particulars was not carried out as thoroughly as it might have been. This was especially true for the tribes, such as the Comanches, that were quickly determined to be on the margin of the Sun Dance trait distribution area, at least as it appeared by the late 1800s. There were also problems in reconstructing tribal histories in the manner Boas recommended. Some of the investigators became frustrated because, often, different tribal elders possessed contradictory accounts of past events that could never be reconciled. And while Spier’s reconstruction of the spread of the Sun Dance has not been significantly challenged, his effort failed to inspire similar studies elsewhere or contribute to larger theories of cultural development. All of the constituent tribal studies remain, however, providing rich detail about the Sun Dance and tribal life in general across the Plains, and they are valuable to later anthropologists as well as to modern Indian people who seek knowledge about their ancestors’ religion.

A contemporary debate reexamines Spier’s contributions and asks whether there is such a thing as the Sun Dance at all. Anthropologist Karl Schlesier (1990) and few other writers have argued that the Sun Dance as such is a fabrication made up by anthropologists to account for diverse tribal ceremonies with varying histories and purposes. This viewpoint looks at much of the same data that Spier observed, plus archaeological evidence of possible forerunner ceremonies, and emphasizes differences rather than similarities and connections. Schlesier’s critique is instructive. It is unlikely that the Sun Dance construct will be abandoned, however, because it is convenient for describing numerous relatable ceremonies, and more importantly, because modern Indian people accept the category and use it in communicating about ritual among themselves and to the larger society.

Sun Dance Survival and Revival

Because the Sun Dance brought entire tribes together for traditional religious expression, it became a major target for government and church officials who wanted to break down tribal society and convert Indians to Christianity. The militarism, harsh ordeals, and authority of the medicine men were all aspects of the Sun Dance that troubled Indian agents and missionaries intent on assimilating their charges. During the Reservation Period and well into the twentieth century Sun Dances were outlawed and physically disrupted. During these times also some practitioners must have concluded that the dance was no longer possible to stage in its true form, since the buffalos were exterminated and other elements of the dance were difficult to include under reservation conditions; or, perhaps, some lost faith in the dance’s ability to renew a desirable world. The newly formed Ghost Dance and peyote religions (see below) may have offered complete alternatives for some Sun Dance worshippers. The steep declines in tribal populations when reservations were first established compounded the effect of all these disincentives. Under such external and internal pressures, some people abandoned the dance. Others continued to practice it, but in secret. Still others were able to maintain occasional public ceremonies despite the disincentives.

By the late twentieth century it was possible to classify the Sun Dances of each tribe originally identified by Spier in four continuation categories (after Liberty 1980):

1. Old traditional ceremonies that had been continued

2. Ceremonies that had been adopted by tribes on the margins of the Plains late

3. Ceremonies among tribes where the Sun Dance had ceased and been revived or reintroduced

4. Ceremonies that were actually or apparently extinct

Six tribes that openly perpetuated the dance were the Arapahos, Assiniboines, Blackfoots, Cheyennes, Plains Crees, and Plains Ojibwas. Except for the Siouan-speaking Assiniboines, this group includes Algonquian speakers and so might be regarded as the resilient ancient core of Sun Dance practice. The presence of the Ojibwas on the list of retainers is interesting because they had relatively few of the ceremonial traits identified by Spier. From their case it is evident that other factors, such as how a ritual is integrated within a language and culture, and the degree of outside interference, can be more important than the number of traits in determining whether a ritual is retained or lost.

Among the Sioux tribes generally, it had appeared that the Sun Dance was extinct around 1900, but in fact some Oglalas (Tetons) did continue to hold dances. Theirs were mostly held in private to avoid persecution, deep in the Pine Ridge and Rosebud reservations. These hidden dances became the foundation for a revival inspired by the Cheyennes and Arapahos, whose dances the Oglalas visited regularly. By the 1960s pressure against the dance had lessened enough to allow frequent public ceremonies among the Tetons.

Two other tribes, the Shoshones and Utes, were able to sustain continuous Sun Dances. Unlike the ancient core continuators, however, the various Shoshone and Ute communities generally adopted the dance only in the late 1800s, and they developed versions that varied most from the typical form, especially through the inclusion of Christian elements.

A number of other tribes lost the dance but revived it from some combination of tribal memory and importation. The intertribal network of communication that developed during the twentieth century involved a lot of sharing of traditions, which helped some tribes restore their Sun Dance. The Crows, who ceased Sun dancing around 1874, sought out Sun Dance leaders among the Wind River Shoshones in 1941 to relearn the tradition, and they reinstituted a ceremony in their own tribe. The Kiowas quit Sun dancing, for good it seemed, in 1890, when Indian agents spread rumors of an impending police action by the army; yet in the late 1990s some Kiowas were experimenting with a revival. The Comanches, whose engagement with Sun dancing was late and experimental according to present evidence, staged some dances prior to 1878 but ceased after that year. Other tribes that appeared to have lost the ritual permanently were the Arikaras, Canadian Sioux, Gros Ventres, Hidatsas, Poncas, Sarsis, and Sissetons. However, as of 2001 only the Poncas, Sarsis, and Comanches had not pursued some kind of revival.

Among the Sioux, the Sun Dance became a powerful expression of cultural identity beginning in the 1970s. The resurgence of Sun dancing coincided with the rise of the American Indian Movement and native civil rights activism (see Chapter 12). Reservation youth previously detached from traditional religion became interested in their roots, and young Oglala men spoke of “wearing scars” from ceremonial piercing as a permanent marker of ethnic pride. If anything, the piercing ordeal became more common and severe in the modern Sun Dance than it had been in pre-reservation times. Urban Indians and Indians from tribes that did not traditionally practice the Sun Dance came to the Sioux reservations to participate in the revival. Tourists who had become accustomed to visiting powwows were attracted to the dance, as were non-Indian seekers of spiritual knowledge, including those associated with the cultural movement called New Age.

There was some backlash to this newfound popularity, as traditionalist ceremonial leaders sought to prevent outsiders’ access to the dances, in some cases by canceling them. Overall, however, during the 1980s there was a proliferation of Sun Dance ceremonies on the Pine Ridge and Rosebud reservations. Rituals became privatized, with individual families or communities staging them, much like the way peyote meetings are sponsored (discussed below). These rituals focused on the well-being of the sponsoring group rather than on the traditional function of pan-tribal integration and welfare. Some Sioux leaders took an ecumenical outlook, advocating the spread of the Sun Dance as an equivalent to other widespread religions. Almost like evangelists, these leaders began staging Sun Dances off reservation, around the United States and in Europe, for participants and audiences that were mostly or all non-Indian. It remains to be seen what forms and functions the Sun Dance will take on in the near future, but it is safe to say that in some manner it will continue as a potent demonstration of the values associated with Indian culture.

THE GHOST DANCE

In 1889 word began spreading across the Plains reservations of an Indian prophet with extraordinary powers and teachings. Wovoka (Cutter), also named Jack Wilson after the white ranch family who employed him, was a Northern Paiute Indian living in Mason Valley, Nevada. There as elsewhere, Indian people were beset with disruptions to their lifeways on account of the influx of whites, and a feeling of desperation was taking hold. It had long been part of the cultural fabric among the tribes to the west of the Northern Plains to conduct ceremonies of world renewal, and Wovoka drew on these traditions as well as Christian teachings to formulate a messianic doctrine.

Wovoka preached of a way that the earth could be regenerated for the reuniting of all Indians. The tribes would live in harmony and the living would be joined again with their departed loved ones. Unhappiness, disease, and death would disappear. The land would be covered over with a new skin of greenery, full of buffalos and other game and devoid of white people. To bring about this change, Wovoka taught, all Indians should join together and repeatedly perform the Naraya or Ghost Dance, an old dance of the region meant to honor the ancestral spirits that had been neglected in recent years. This doctrine was inspired in Wovoka through a series of visions when he fell into a deep illness that coincided with a solar eclipse; he believed that he was taken to heaven and given the doctrine by Jesus and other supernatural figures.

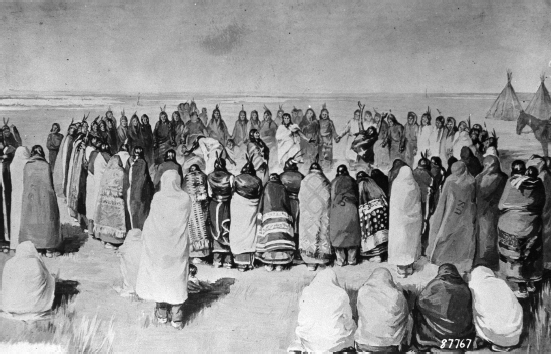

“You must not fight. Do no harm to anyone. Do right always,” Wovoka urged his followers (Mooney 1965:19). His message emphasized peaceful readjustment of the world order through hard work, clean living, obedience to movement leaders, and above all, fervent dancing. The dance itself was an adaptation of the common round dance, in which male and female dancers form a large circle (facing inward), hold hands, and step clockwise by opening and closing their legs in unison to the rhythm of songs. The hypnotic intensity of the dancing was unusual, however. Worshippers danced for hour upon hour, until they passed out. The dreams they had while collapsed provided further spiritual messages. Frequently they reported seeing their dead relatives, a preview of the new world to come. A host of new songs were composed for the dance, their lyrics expressing a sense of distress, alluding to key symbols of spiritual flight such as birds, and urging perseverance and optimism. The ceremonies were emotional and memorable. In 2005, Carney Saupitty, Sr. of the Comanche tribe described the dance to the author in vivid detail, in images handed down from his father and grandfather, who had witnessed many Ghost Dance sessions.

Throughout the Plains, conditions of defeat and reservation poverty made many tribal communities receptive to the new movement. The custom of intertribal visiting continued once the reservations were established, and word of Wovoka’s teachings spread quickly. Sign language speeded intertribal communication, as did the new institutions of the railroad and the U.S. mail. As word spread, Wovoka’s reputation and teachings were elaborated. Wovoka came to be regarded by some as the Son of God, and it was said he bore the scars of the crucifixion on his hands and feet. He was credited with miracles. Some tribes sent emissaries to Nevada to see for themselves. The Tetons Short Bull and Kicking Bear were part of a large delegation from the Sioux, Shoshones, Cheyennes, and Arapahos. The Kiowa Apiatan (Wooden Lance) came back to his people reporting that the messiah was an ordinary man, and so a fraud, yet many Kiowas still became involved. In all, components of over 20 tribes took up the Ghost Dance, including the Shoshones, Assiniboines, Gros Ventres, Arikaras, Mandans, Sioux, Arapahos, Cheyennes, Comanches, Pawnees, Poncas, Otoes, Missourias, Kansas, Iowas, Osages, Kiowas, Kiowa Apaches, Caddos, and Wichitas, as well as displaced eastern tribes in Indian Territory and some tribes of the far west.

On the Northern Plains, Wovoka’s message was transmuted and took on a militant tone. The spread of the Ghost Dance in the north coincided with growing hostility and resistance to non-Indian activities in the region, such as the invasion of gold miners and desperadoes in the Black Hills, the intrusion of rail lines, the extermination of the buffalo, and the general failure of the government to keep treaty promises and provide reservation supplies. A belief developed among the Sioux that if Ghost dancers wore special muslin shirts decorated with religious symbols, called ghost shirts, while they danced, they would be impervious to bullets. Soon the religious movement became conflated with political resistance in the minds of non-Indians, who became especially fearful about an uprising of Indians who were dancing themselves into trance en masse and who believed themselves bulletproof. U.S. Army leaders in particular were suspicious that the Ghost Dance fervor would contribute to an uprising. The annihilation of the Seventh Cavalry under General George Armstrong Custer at Little Big Horn in 1876 was still on everyone’s minds, and the northern reservations had not been settled to the extent that the army had developed stable relations with the Indians of the kind that would foster a detailed understanding of their motives.

Army troops moved into the five Sioux reservations in South Dakota in anticipation of an outbreak, while reservation agents began ordering a stop to the dancing and intertribal visiting. When the Sioux medicine man and Little Big Horn veteran Sitting Bull, a recent convert to the Ghost Dance religion, and his followers ignored these orders, Indian police and soldiers were sent to arrest him. The apprehenders went to Sitting Bull’s cabin on the Standing Rock Reservation on December 15, 1890. One of Sitting Bull’s group opened fire, killing an Indian policeman, and in the subsequent exchange of fire, Sitting Bull along with eight of his supporters and six more Indian police were killed.

In the days that followed, troops of the Seventh Cavalry marched on a camp of some 3,000 Indians who had assembled in the Badlands north of their homes on Pine Ridge Reservation in the hope that the deliverance promised by the Ghost Dance was imminent. The troops surrounded them and drove them back to the reservation, to a site on Wounded Knee Creek, where they were to be disarmed and dispersed. On the frigid morning of December 29, as the Indian men turned in their guns, one opened fired on the soldiers. A bloody melee erupted in which a number of Indians and soldiers were killed in close combat. The soldiers then trained their weapons, including four Hotchkiss mechanized light cannons, on the Indian women and children, mowing them down in the snow without mercy. Those fleeing were pursued into a ravine, where the havoc continued. Some 300 Indians were killed, the majority women and children, as well as 31 soldiers. The Wounded Knee massacre put an immediate end to the Ghost Dance religion among the Northern Plains tribes.

On the Southern Plains, circumstances were different and the Ghost Dance movement wound down peacefully. The reservations there had been relatively stable for about 15 years and military and civil authorities had close and frequent contact with the Indians. Some soldiers knew the Indians well; they conversed with them in different languages, including sign language, understood their cultures, and worked with them closely in Indian military units. As the Ghost Dance fervor grew, and news of the Wounded Knee tragedy came south to Indian Territory, non-Indians there did become alarmed and watchful. The leader of the dance among the Pawnees was jailed for several days in 1891. But key army officers, notably Lieutenant Hugh L. Scott at Fort Sill, urged their superiors not to overreact. Scott heard directly from I-see-o, a Kiowa scout, and other Indian contacts that the religion was teaching peaceful coexistence. He concluded, that many of those who were currently interested in Wovoka’s message were likely to become jaded with the promises of the new belief system over time. Scott also learned that many of the Indians remained skeptical. While many Kiowas were embracing the dance enthusiastically, most of the Comanches were reluctant to get involved with the teachings of a new prophet, for a few years earlier some of them had followed a Comanche seer into battle and been severely beaten. Confident in his analysis of the situation, Scott persuaded the army not to use force. He prevented another tragedy and the movement eventually waned as he predicted.

The Ghost Dance faded in the south and far west over a long period. Dances were held through the 1890s and into the 1930s. During the same period, peyotism and Christianity came into prominence in Indian communities, offering different methods for imagining a better world. Gradually the Ghost Dance and related songs became disassociated from any expectation of imminent world renewal, and they simply became elements in more general worship and recreational activities. In the 1990s, Ghost Dance songs could still be collected among the Cheyennes and Shoshones, and a distinctive cow horn Ghost Dance rattle from long ago hung on the wall for decoration in the Comanche home the author lived in during fieldwork. Wovoka himself desisted from his preaching after learning of the violence that had ensued. He repudiated the idea of protective shirts and discouraged further visits from tribal delegates. By the mid-1890s he had retired into a private existence, and he died in October 1932.

The Ghost Dance and the Origins of Religion

It has been observed that the pattern of development of the Ghost Dance resembles that of many other religions throughout human history. Because it had a relatively brief and definable period of development, the Ghost Dance has frequently been discussed not simply as a “religion” but as a “religious movement,” this term emphasizing the dynamic rise and fall of the belief system in relation to changing social circumstances. In particular, viewing religious behavior as a movement draws focus on the ways in which social, political, or economic aims seek expression in religious form. Defined as a movement, the Ghost Dance is easily likened to other cases. It could be classified as a “messianic movement” because, like many other religions, it was founded by a single charismatic prophet whose teachings provided a recipe for salvation. Or, the Ghost Dance could be referred to as “millenarian movement,” one in which there is the promise of a second coming or world made new. With its focus on a return to aboriginal ways and rejection of introduced cultural elements, the Ghost Dance may be regarded as a “nativistic movement,” or as a “revitalization movement” because of its purpose in regenerating the older cultural forms and ways of life. These categories themselves have a long history of development within the cross-cultural study of religion; they are related and somewhat overlapping. Each of the categories depicts religion as a form of resistance to changing social, political, or economic circumstance.

The anthropologist James Mooney, who interviewed Wovoka and documented the rise of the Ghost Dance firsthand, was the first to draw similarities between the Ghost Dance and other movements throughout history. Mooney compared Wovoka to prior Indian resistance leaders, such as Popé, leader of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, Pontiac, and Tecumseh. Mooney also drew comparisons with the Celtic King Arthur, Joan of Arc, and the Hebrew Messiah. In selecting such examples, Mooney reveals his opinion that messianic promises led inevitably to bloody confrontation and the dashing of millennial hopes. No doubt this opinion helped Mooney rationalize the violence he saw unfolding on the Plains. In fact, there are also cases in which a messianic message not only failed to stimulate violence, but also gave rise to stable and long-lasting belief systems. The religion founded by the Seneca prophet Handsome Lake in the 1700s, still practiced today among the Iroquois, is one such example.

A later theorist went forward with a more thoroughly developed version of Mooney’s hypothesis, arguing that the Ghost Dance can be viewed as a template for understanding how all religions came into being. The psychological anthropologist Weston LaBarre amassed dozens of cases from throughout human history to demonstrate a recurring pattern of religious development. All religions, he concluded are born out of the tensions resulting from the collision of differing cultures. All offer other worldly explanations and solutions for these worldly stresses, become appealing to a downtrodden population, and take hold, some only temporarily but some with great durability. LaBarre’s proposed pattern is very much like the concept of revitalization movement in highlighting religion’s function of relieving psychological stress. LaBarre argued that even such a widespread and mainstream religion as Christianity, which is not normally likened to the belief systems of small-scale societies, actually conforms to the Ghost Dance pattern in the early days of its history, with its origins in military oppression (Romans over Jews), its messiah, and its promise of a second coming.

These comparisons should in no way demean the beliefs or experiences of the Ghost dancers or cause us to gloss over the unique aspects of the Native American religion. They do, however, lend understanding about the needs and motives of the Ghost dancers, by showing that they are ultimately very typical in human experience through the ages.

YUWIPI

Despite all kinds of introduced spiritual and medical beliefs, nativistic communal healing ceremonies have persisted to the present day. Healing rituals are not easily distinguished from those intended for world renewal, since the reestablishment of a person’s physical wellness requires remaking of balance in the universe. Some group rituals, however, clearly use the healing of one or more individuals as their point of departure or main goal. A prominent example of a contemporary healing ritual is the yuwipi of the Teton Sioux. The yuwipi is a presumably ancient procedure that is still performed frequently, and it is elegant in the way it expresses Indian concepts of wellness and morality.

The Lakota term yuwipi refers to binding, for the pivotal activity of the ritual is the tying up and unbinding of a medicine man. Among the Sioux, the term “yuwipi man” is used more or less interchangeably with “medicine man.” The yuwipi man is capable of prophesizing, finding lost objects, advising others how to live a proper life, restoring health, and convening the spirits to aid humans, much like curers throughout Indian America. These men frequently are leaders of other ceremonies too, such as the Sun Dance. But they are especially known for their ability to escape, with the aid of only the spirits, after being tightly bound in a wrapping of quilts and ropes. Frank Fools Crow (1890–1989) and George Plenty Wolf (1901–1977) were two of the most influential yuwipi men in the Lakota community during the twentieth century.

The setting for this operation is a one-room cabin cleared of its furnishings and darkened with blankets over the windows. Previously someone feeling sick or out of step with life has approached the yuwipi man with a humble plea for aid. They may be facing a serious illness, or uncertainty about school or their job, or perhaps something more mundane—their favorite horse and saddle have gone missing. Sometimes the patient is a young man who has pledged to conduct a vision quest at the same time as the yuwipi, to benefit from its supporting effect. The patient has brought a pipe to the healer four times and presented it, with a description of the problem, in a formalized appeal; in accepting the pipe, the yuwipi man has agreed to help. Now, as night falls (the rite is also called hanhepi woecun “night doings”), relatives and friends of the patient, from old people to children, gather in the cabin under the direction of the medicine man.

On the bare plank floor, the medicine man sets up an altar space outlined with flag-bearing willow wands planted in dirt-filled coffee cans, representing the six directions, and a string of small tobacco offerings (representing the numerous helpful spirits) that completely encloses the area. Within this zone a seventh willow wand marks the center of the universe, and here the yuwipi man makes his small altar by spreading dirt from a mole hole, symbolic of the uncontaminated sacredness of the subterranean world, on the floor. A pallet of sage sprigs is laid out by the altar and a smaller string of tobacco offerings, denoting the most powerful spirit helpers, encloses the altar and pallet. Also placed in this area are rattles that will be animated by the visiting spirits, and rawhide ropes and a star quilt for binding the yuwipi man. As the altar space is finished, participants sit down all around on chairs or blankets.

An assistant ties the yuwipi man’s arms behind his back, wrapping the bindings carefully around his fingers, hands, wrists, and arms. Then he covers the leader head to toe with the quilt and ties it tightly. The bundled medicine man is lain face down on the bed of sage and the lights are put out. Designated singers, drummers, and the rest of the participants join together in a long sequence of songs which outline the unfolding spirit visit: preparation, calling the spirits, asking them for help, and asking them to leave in kindly fashion. They intone (Steinmetz 1990:66),

Tukasila wamayank uye yo eye |

Grandfather, come to see me |

Tukasila wamayank uye yo eye |

Grandfather, come to see me |

Mitakuye ob wani kte lo eya ya, hoyewayelo eye ye |

So that my relatives and I will live, I am sending my voice |

Soon the participants become aware of little flickering blue lights appearing here and there in the pitch-black room. Odd sounds begin erupting all around. They hear groans coming from different directions, and the sounds of the rattles and drum seem to bounce all about the room. Words of advice or inspiration are being whispered in their ears. Some of the talk is humorous. They feel pounding on the floor around their feet, and one or another might catch a slap to the side of the head. A breeze wafts through the room suddenly. The spirits who have been summoned have arrived and they are making their presence known.

The yuwipi man begins talking to the spirits—participants can hear his side of the conversation, but not the replies—and he informs the sacred visitors of the problems that need intervention. Participants interject “hau” to affirm his statements. When the yuwipi man has had his say, others in the room may also beseech the spirits, adding their own plights to those of the main patient.

After some time the commotion and talk subsides and the yuwipi man calls for the light to be turned on. He is found sitting calmly amid the strewn wreckage of his altar, the quilt and ropes neatly folded nearby, and the string of tobacco offerings rolled in a perfect ball. A feeling of relief comes over the group and the meeting disbands.

From an anthropological viewpoint, the yuwipi man has served as a mediator, bringing the spirits among the people by putting himself in a plight. As they rescue him, they become available to pity and help his followers. In the darkness of the cabin, the mischievous spirits make disorder from order, and then once again establish normality. The medicine man uses sleight of hand techniques and ventriloquism to enhance the feeling that the spirits are present, and his unbinding, also accomplished with the skills of an illusionist, is given as further evidence of their visit. The unbinding represents the peoples’ release from their troubles. And whatever the specific cures that are effected, it is understood that the meeting has united the participants socially in a way that is lastingly beneficial to tribal well-being. The saying Mitak’ oyas’in, “All my relations,” proclaimed at various times throughout the meeting, draws attention to this integrating function.

PEYOTISM

The last major Native ceremony that became significant among the Plains tribes involves the ritualized eating of the hallucinogenic cactus peyote. Even though the present form of the peyote religion arose during the early reservation era and has thus been well documented, it remains clouded by misperception because it is practiced in private and uses a substance that outsiders have wrongly equated with dangerous drugs. It is important to understand the peyote religion in its own terms, as a richly meaningful expression of traditional Native values.

Origins of Plains Peyotism

One of the original scholars of the peyote ritual, Weston LaBarre, noted that while many psychoactive plant products were known to Indian peoples in South America, relatively few were found in the northern hemisphere, and most of these were found in Mexico and the southern United States. In these areas, drugs were sometimes used to sedate sacrificial victims and captives, to promote endurance during ceremonies, hunts, and ball games, and for making prophecies about where game or enemies would be found. Tobacco is the most common and widespread narcotic in Native North America, though a mild one. The Aztecs used teonanacatl (“divine mushroom”), a hallucinogenic mushroom. In the Southwest and California culture areas, parts of datura or jimson weed, though poisonous, were eaten or drank as tea by several tribes to achieve a ritualized delirium, and some Apache groups brewed corn beer. The so-called black drink, made by steeping the caffeine-rich leaves and twigs of the yaupon holly (Ilex sp.), was taken ritually by Indians in the southeast United States and eastern Texas for purging and to promote a nervous delirium conducive to visions.