There is nothing more important for our economic future—or less understood—than the federal budget. It allocates around 20 percent of our national output to such crucial priorities as health, education, science, the environment, and national defense. It determines, to a large extent, how many Americans suffer from poverty and even the level of inequality in incomes. And yet our national debates on economics, and the positions of both Democratic and Republican leaders, obscure more than they reveal about the choices facing the nation.

Here’s why. While people have a reasonable sense of their own budgets, they have little sense of how Washington taxes and spends. We may know well what an extra $1,000 might mean for our own standard of living or ability to pay the bills. But what does $1 billion mean at the national level? (Hint: With 320 million Americans, $1 billion is a mere $3 per person). Or what does $1 trillion in infrastructure spending over five years signify? (Hint: With GDP of nearly $20 trillion per year, $1 trillion over five years amounts to roughly 1 percent of national income per year.)

Our starting point is that the fiscal situation of the United States is already precarious. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the budget deficit during the coming decade, should we stick with existing policies, is likely to average around 4 percent of GDP. Increases in spending on infrastructure, public services, or the military would add to a large and rapidly growing stock of debt.

To solve our economic problems, we need to overhaul our understanding of the budget, the role of government, and the nature of fiscal policy. Neither party yet offers a realistic solution. President Obama presided over a slow drip of gradual decline, rising debts, and stagnation. President Trump proposes to boost spending, especially on infrastructure and the military, but also to cut taxes sharply. It doesn’t add up, to say the least. Or more accurately, it adds up to a massive and debilitating debt crisis down the road. We will need a better way.

Our starting point should be the pithy observation of former Vice President Joe Biden: “Don’t tell me what you value; show me your budget, and I’ll tell you what you value.” The federal budget is an expression of what we value as a nation because it shows how we choose to allocate our national resources.

Values without a budget are empty words, election promises that are at best naive and, more typically, cynical lies. Obama’s “Yes, we can” promises of 2008 failed precisely because there was no long-term budget plan behind them. That was true even when, in 2009 and 2010, Obama had large Democratic Party majorities in both houses of Congress. In fact, Obama’s failure to deliver on his uplifting 2008 campaign was baked in from the start, from his very first budget proposals, which failed to call for an increase in federal revenues to pay for increased outlays.

Here, in brief, is how the federal budget works. On the one side we have the revenues raised by federal taxes and, on the other side, the outlays. Federal taxes take in about 18 percent of GDP, mostly from income taxes and payroll taxes (for Medicare and Social Security). Together with state and local taxes, the total tax collection of all levels of government amounts to around 32 percent of GDP. Let’s keep that number in mind.

On the federal spending side, we have four main categories. The first is national security. That entails the Pentagon, intelligence agencies, homeland security, the Energy Department’s nuclear weapons programs, other international security programs in the State Department, and the Department of Veterans Affairs (the delayed costs of past wars). In total, annual outlays now total around $900 billion per year, or roughly 4.9 percent of GDP.

The second category covers so-called “mandatory” programs, including health (Medicare, Medicaid, other health), Social Security, and income support programs (such as food stamps). These total around 12.6 percent of GDP. Their costs have been rising as a share GDP in recent years because of the aging of the population and the soaring costs of health care. The rising outlays due to aging will, of course, continue.

The third category is interest payments on the government (public) debt. With the ratio of public debt to national income now around 75 percent and the average interest costs on the debt around 2 percentage points per year, the interest charges are around 1.5 percent of GDP. These costs will rise when interest rates return to more normal, higher levels.

The fourth category of spending, sometimes called “nonsecurity discretionary programs,” includes the federal government’s investments in the future, such as biomedical research, other science and technology, low-carbon energy R&D and deployment, education and job skills, fast rail and other public infrastructure, the courts and penal system, and a small amount (a meager 0.2 percent of GDP) for helping the world’s poorest countries to fight hunger, illiteracy, and disease.

The astute reader will have already spotted the problem. Tax revenues total around 18 percent of GDP. Yet outlays for the first three categories (national security, mandatory programs, and interest on the debt) total around 19 percent of GDP! Revenues do not even cover the first three categories, much less the crucial fourth category. Borrowing, rather than tax revenues, must therefore pay for the entire nonsecurity discretionary budget, a dreadful and unsustainable situation.

The simple truth is that America doesn’t raise enough tax revenues to finance the key public investments for our future. Instead of investing federal funds adequately in higher education, we pile a trillion dollars of student debt on the backs of our young people. Instead of upgrading our infrastructure, we drive on crumbling highways and bridges. Instead of building a low-carbon energy system, we continue to rely on coal, oil, and gas, endangering the entire planet as a consequence.

President Trump says he will solve these problems, but with what funds? As a candidate, then-Senator Obama said the same in 2008 and ran into a dead end. Instead of investing in our future, Obama has presided over cuts in the nonsecurity discretionary programs, with budget allocations declining from around 2.6 percent of GDP in 2008 (just before Obama came to office) to a meager 2.3 percent of GDP in 2016. The projections are even more ominous, with nonsecurity discretionary spending on a trajectory to decline below 2.0 percent of GDP by around 2020.1 Crucial federal programs remain on life support as budget outlays for key public investments continue to fall.

What is the way forward if we want to invest in a twenty-first-century future rather than suffer from continued stagnation and decline? Most importantly, we will need to think out of the box. The first strategy should be to cut back on wasted federal outlays. The biggest saving should be on the military side. Despite the reflexive call to boost military spending, we should instead end the perpetual Middle East wars, cut back sharply on America’s overseas military bases, and negotiate sharp global limits on nuclear arms rather than invest in a new, costly round of the nuclear arms race. In a later chapter, I will also detail the ways that our nation can save on total health outlays, albeit by shifting part of the today’s private health spending onto the federal budget with big offsetting reductions in private health spending.

Significant budget action, however, will have to come on the revenue side. We have refused, since Ronald Reagan became president in 1981, to fund the federal government adequately despite the realities of an aging population and the urgent need to invest in advanced skills, education, infrastructure, and environmental sustainability. Reagan told us in 1981 that government was the problem, not the solution; Democratic Party presidential candidate Walter Mondale got buried in Reagan’s 1984 landslide after Mondale said that he’d raise taxes. Since then, both parties have simply denied the need for more revenues built up public debt instead. We are now running on fumes, funding the entire nonsecurity discretionary budget with a bulge in public debt.

For a while, the so-called “progressive” idea was simple: Instead of calling for higher taxes, progressives would proclaim that borrowing was just fine. Paul Krugman told us time and again not to worry about the public debt, that it’s actually good for us, by stimulating demand while not adding much to future tax burdens. Many Republican supply-siders said the same, though their spending priorities were typically different (usually calling for more military spending).

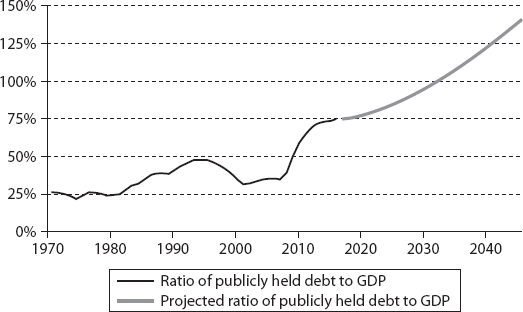

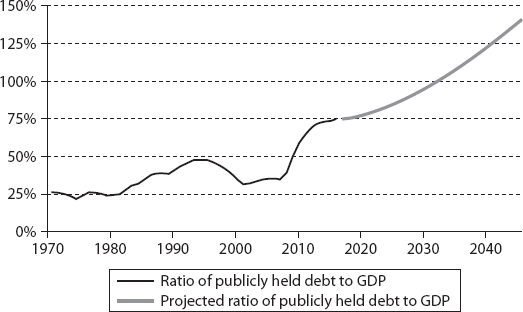

That was then. In 2007, the debt-to-GDP ratio was 35 percent; now it’s 75 percent. Given current trends and policies, according to the Congressional Budget Office, it will be around 86 percent in 2025, and in 2036 will reach a staggering 110 percent of GDP (figure 3.1).2 Today interest rates are low; in the future, when they’re back to normal, at around 4 percent per annum, the debt burden will hit very hard indeed, requiring at least 3 percent of GDP, if not more, to pay for interest payments.

FIGURE 3.1 Long-Term Trend of Public Debt on Unchanged Policies (percent of GDP)

So how do other countries manage their budgets? Simply, they tax more as a share of national income. The United States taxes around 32 percent. Canada, with its highly successful public sector programs in health and education, taxes at around 39 percent (and it’s still thriving!). The Scandinavian social democracies—Denmark, Norway, and Sweden—tax around 50 percent of GDP. And yes, they get great value for money, with smaller budget deficits, lower debt-to-GDP ratios, at least a month per year of paid vacation, free public health care, free college tuition, guaranteed maternity leave and quality child care, modern infrastructure, and much greener economies.

Despite their higher tax rates (or, more accurately, because of the social services these taxes purchase), the Scandinavian countries and Canada rank much higher than the United States in overall national happiness. In the 2016 rankings of national happiness, the top six countries were Denmark, Switzerland, Iceland, Norway, Finland, and Canada, with the United States coming in thirteenth.3 All of the top leaders in national happiness collect more in tax revenues as a share of GDP than the United States, thereby paying for an ample array of public investments and public services that contribute to prosperity, greater equality, and higher self-declared happiness.

So how can the United States fund its future and collect more revenues without damaging the incentives to save and invest? Part of the answer lies in ending absurd tax giveaways, like the gimmicks that have allowed Apple Inc. and others to keep their profit stashed abroad in tax havens. Ending corporate abuse could garner around 1 percent of GDP. Another 1–2 percent of GDP could come from wealth and income taxes on the super rich.

Yet, as in Scandinavia, I would also recommend a value-added tax (like a national sales tax), enough to raise another 3–4 percent of national income. The total federal revenues would thereby reach around 24 percent of GDP and around 38 percent for combined federal, state, and local government. This would be roughly equivalent with Canada and still well below the revenues of northern Europe. At least the United States would be in a position to think about investing in our future once again.

As a candidate, Trump seemed to suggest most of the infrastructure scale-up, and his stated desire for increased military outlays, could be paid for with more debt. Pursuing this as president would be a mistake, a major burden on the future, and one that would likely fizzle out in a fiscal crisis at the end of a populist boom in spending. Part of the infrastructure spending can indeed be financed by public debt (especially for infrastructure that will directly generate future tax revenues), but not all of it, especially when the baseline trajectory of public debt is so ominous.

Republicans are looking for cuts in the corporate tax rate in order to keep American-based companies competitive with international companies. There may be some merit to cutting the top corporate tax rate if combined with an end to corporate loopholes and the foreign tax deferral provisions. But the more basic deal should be to combine any corporate tax reform with the introduction of a VAT or similar tax (such as a progressive consumption tax) in order to ensure that total revenues relative to GDP are increased adequately to cover future needs.

Such ideas are currently outside of the political mainstream, but I believe that they will return to the center of national politics as the American people realize that both parties are shortchanging their futures. Senator Bernie Sanders ran his campaign on mobilizing vastly more revenues for much greater public investments. He decisively rallied the young. I believe that this message will soon come to the fore of our national politics more generally; it is vital for our economic future.