More than any other threat facing America is the collapse of civic virtue, meaning the honesty and trust that enables the country to function as a decent, forward-looking, optimistic nation. The defining characteristic of the 2016 presidential election is that neither candidate was trusted. The defining characteristic of American society in our day is that Americans trust neither their political institutions nor each other. We need a conscious effort to reestablish trust, by making fair play an explicit part of the national agenda.

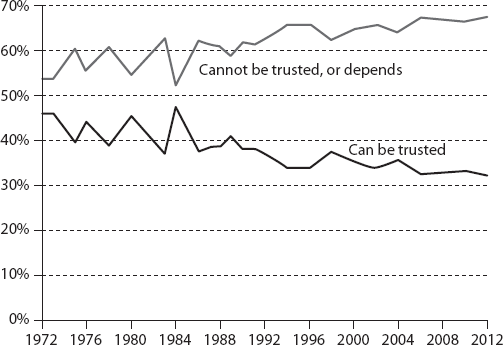

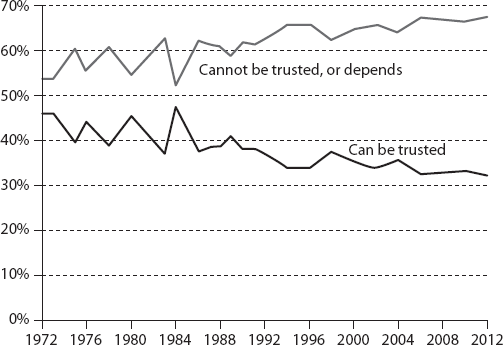

We have already noted the collapse in public confidence in the federal government. The collapse of trust in each other is equally striking. For decades, pollsters have asked Americans whether “most people can be trusted.” And for decades, the proportion answering in the negative has been rising (figure 13.1).

FIGURE 13.1 Americans on Whether “Most People Can Be Trusted,” 1972–2012

There are probably two main reasons for this downward trend. The first is the sharp widening of income inequalities since the 1970s. The second is the widespread feeling that those at the top of the heap in income and power regularly abuse their wealth and influence. Donald Trump’s relentless assertion in the 2016 campaign was that the system is “rigged,” a claim that resonated widely despite the obvious irony that Trump himself has been a relentless rigger of the system.

The system is indeed rigged for the big corporate interests such as the drug companies that set drug prices a thousand times the production cost. It’s rigged for the large IT companies such as Apple Inc. that deploy egregious tax loopholes that enable them to park their funds overseas in tax-free offshore accounts. It’s rigged for the hedge fund managers who take home hundreds of millions of dollars in pay and then face a top income tax rate of 20 percent, far below what other, vastly poorer Americans must pay. It’s rigged for the investment bankers that deliberately cheated their clients and then walked away with a mere slap on the wrist, if that. And the fact that the Clintons parlayed public office and a family foundation into a vehicle for vast personal enrichment was not lost on an unhappy and distrustful electorate.

Considerable social science research in recent years has given laboratory evidence to an ancient truth: that power and wealth indeed corrupt. Consider a fascinating psychology experiment published recently in Nature, a leading scientific journal.1 The employees of a major international bank were divided randomly into two groups, a “control” group and a “treatment” group. Both groups were given forms to fill out at the start of the experiment. The control group was asked general questions. The treatment group was asked questions about their role in banking. Then each group was asked to flip coins and report honestly how many “heads” they flipped, being told that a greater number of heads would lead to a higher monetary award.

The control group reported that they flipped around 50 percent heads, an honest report. The treatment group claimed to have flipped around 58 percent heads, a dishonest report that exaggerated the proportion of heads flipped. The conclusion: Simply by being reminded that they were bankers (by filling out a form about banking), the treatment group was spurred to cheat. The psychologists concluded that the business culture of banking within that representative bank was a culture of cheating and greed.

One feels that America is like that today, especially at the top. This is an age of impunity, a time when the rich and powerful get away with their misdeeds, and are even lauded for them in some quarters. Donald Trump met the accusation that he had not paid income taxes for years with the response, “That makes me smart.” Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein met the charge that his bank had cheated its customers with the response that they were “doing God’s work.” Hedge fund manager John Paulson was celebrated on Wall Street for his “cleverness” in conspiring with Goldman Sachs to bilk a German bank of hundreds of millions of dollars. The leaked emails showing how the Clintons mixed their public, private, and foundation activities simply confirmed for many unhappy Americans that this is how the system works.

The United States Supreme Court has shamelessly fed the impunity. In the infamous Citizens United case, the Supreme Court shockingly equated anonymous corporate contributions to political campaigns with free speech. The Court demonstrated that it had no realistic sense about how such corporate contributions have undermined the legitimacy of the political system. In a more recent case, the Supreme Court overturned the conviction of former Virginia governor Robert McDonnell, who had been convicted of fraud and extortion for taking gifts from a businessman promoting his health products to the state.2 McDonnell walked away free from a shoddy and egregious abuse of office.

I have noted repeatedly that other high-income countries do not face these same trends. The U.S. pattern of rising inequality, falling trust, and increasing money in politics is not simply a reflection of the times or an inevitable side effect of democracy in the twenty-first century. Indeed, while many other countries are caught in a similar spiral of rising inequality, falling trust, and increasing corruption, many others are not. Canada, for example, has successfully avoided these extremes, even though we share a common North American economy and a 3,000-mile border. Decency and trust can be maintained even in our complicated, globalized times.

While there are no magic wands to restore social trust in the United States, there are important guideposts for citizens, businesses, and public officials. I suggest six key steps.

First, we should acknowledge the dangerous hold of the lobbyists and the super-rich on the political process. While many incumbents in office today will not sever their ties with their campaign contributors, citizens should sever their ties with politicians who rely on such contributions. Citizens’ movements, social networks, and new political parties should establish a new norm for the coming elections: that they give political support (and small-scale donor support) only to candidates who reject large contributions from the rich and corporate interests. Campaign finance reform may arrive someday, but before that date it will be possible achieve progress by electing politicians not on the take.

Second, we should recognize that the rising power of the richest Americans has been key to the rising impunity in America today. Canada and the countries of Scandinavia have kept the lid on impunity by erecting legal, tax, financial, and cultural barriers to the accumulation of vast wealth and its insidious deployment in the political process. Yes, there are the very rich in all societies, but their outsized role in America’s politics has been distinctive compared with the other high-income democracies.

Third, corporations are not people, despite the Supreme Court’s confusion on this score. They are harder to shame, and are impervious to threats of imprisonment. For this reason, the rampant criminal activities of many powerful companies call for individual culpability of the CEOs and the corporate boards. When a major Wall Street bank pays billions of dollars in fines for egregious financial malfeasance, the CEO and board members should face personal accountability. This could include removal from office, banishment from the industry, and in justified cases, direct criminal indictment. Such individual accountability has been almost completely absent following the 2008 financial crisis. The CEOs who oversaw their companies’ malfeasance were more likely to enjoy a state dinner at the White House than to face a day in court.

Fourth, the corporate doctrine of “shareholder responsibility” should be replaced, both legally and ethically, with a standard of “stakeholder responsibility.” The difference is this: If a corporation today can get away with an action that boosts shareholder wealth by imposing harms on others, the prevailing corporate ethos is to take the action, especially if the action is deemed to be legal though damaging to the others. For example, in the name of shareholder profits, a drug company may boost the price of drugs to levels that cause great suffering; a company may pollute the air and water to avoid costs if the pollution is otherwise not illegal; a bank may aim for a quick and dirty profit by selling a toxic security to an unsuspecting buyer. In the stakeholder approach, such actions would be firmly rejected. The CEO and corporate board would aim only for policies that truly add value to society (true value added), not for policies that create shareholder value by imposing costs on others. Of course many companies already abide by such a standard, but many of the most powerful clearly do not, and even express their disdain for any restraints on their ability to maximize shareholder wealth.

Fifth, our former presidents and politicians need to exercise restraint in their money making. Barack Obama should break the recent pattern. Bill Clinton and Tony Blair decided to cash in after leaving office, creating the current atmosphere in which it seems that anything goes. Countless senators and congressmen have departed from Capitol Hill directly to K Street, from holding political office to lobbying their former colleagues. The practice is despicable and deserves the public’s opprobrium. Of course, such behavior should also be blocked by a formal code of conduct and legislation. To achieve such reforms would require a strong and concerted public outcry.

Sixth, and most fundamentally, only by acting directly to reduce the inequality of wealth and income in the ways that I’ve outlined in earlier chapters—through fiscal redistribution, universal access to health and education, and environmental justice—can we restore the sense of a democratic system that is truly “of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

The American people have still not heard a word of remorse from Wall Street CEOs for the 2008 crash; nor from the politicians for their egregious self-dealing and murky confusions of public office and private wealth; nor from the Supreme Court for handing America its most money-drenched politics in modern history; nor from the drug companies for jacking up drug prices to levels that are killing many Americans; nor from the hedge fund managers who have engineered tax breaks beyond egregious; nor from the CIA that has implicated Americans in endless failed wars and thereby endangered our lives with rising threats of terrorist blowback.

American disgust in the 2016 election was neither deplorable nor especially hard to understand. It was a rebuke to impunity. The anger will continue until the American system of governance, both public and private, is oriented around the common good rather than the private wealth and power of America’s governing elite.