2 |

The importance of your interpretations |

Nobody else I know feels the way I do. I am so lonely. I wish I knew why I am this way.

Fiona, 37

All the different CBT treatments for anxiety disorders are based on the view that a major problem is that you believe that you are in a situation which is dangerous and threatening to you. In other words, the problem is the way you are interpreting the situation. We know that when you are suffering from anxiety this is a very hard concept to take on board, and it may sound as if we are not taking seriously how distressed you are, but this idea is central to CBT so let’s look at what it actually means.

Cognitive behavioural therapy talks a lot about ‘interpretation’, so it is worth trying to clarify what we mean by this. When we say ‘interpretation’ we do not mean that you are consciously or deliberately weighing up situations – well, not usually anyway – but all of us need to make sense of the world around us, and so we are constantly evaluating situations without even being aware that we are doing it. What we are aware of are the thoughts (sometimes) and feelings (usually) that result from our evaluation. We all have shortcuts in the way that we do this. Unfortunately, in anxiety, the shortcuts are usually along the lines of ‘if in doubt, treat this situation as dangerous’. This is what we mean when we say that you see situations as dangerous and threatening even when they are not. Some cognitive therapists refer to interpretations as ‘appraisals’, or ‘personal meanings’ or ‘personal significance’. For most purposes these different terms – interpretations, appraisals, explanations, personal significance and personal meaning – all refer to the same thing, the meaning of the situation to you, created by your way of evaluating the situation. It is because the anxious interpretations so often distort the reality of the situation and don’t follow the facts that we often refer to them as ‘misinterpretations’.

We thank Professor Paul Salkovskis for his very clear way of explaining this using the ‘dog mess’ joke:

Four people go outside and step in dog mess. The first, who is depressed, thinks, ‘There you go, I’m useless, I can’t do anything right and I may as well go back to bed’. This person feels sad and low. The second, who is anxious, thinks, ‘Oh no, I’ve stepped in dog mess, I will need to change. What if I am late for work? What if I am fired?’ This person feels highly anxious. The third, who has problems with anger, thinks, ‘If I find the b**?!d that let his dog s*!t on my doorstep I will beat him up so badly that he’ll never walk another b**?!y dog again.’ This person feels angry. However, the fourth, who has had cognitive behavioural therapy, thinks, ‘Well at least I remembered to put on my shoes.’ This person feels pleased.

The point of this joke is to illustrate that all these people had the same unpleasant situation of stepping in dog mess, but it was their interpretation of the situation that led to their particular emotional reactions. This is a fundamental principle of CBT – it is not the event that causes you to feel anxious but your interpretation of the event.

Let’s look at another example that illustrates this further. Imagine that you are lying in bed one evening. Your partner is away for the night so you are alone in the house. Suddenly you hear a rattle at the back door. You might think, ‘Oh no, someone is breaking in; they are going to kill me and take everything.’ Or you might think, ‘Oh bother, the stupid catflap is stuck and the cat can’t get in.’ Or you might think, ‘Oh good, perhaps my lovely partner has come back early.’ Furthermore, these different explanations, or interpretations, would result in very different feelings. In the first case you would feel frightened, in the second probably rather irritated, and in the third very pleased. So, the same situation – a rattle at the back door – can be interpreted in different ways, and as a result will produce different emotional reactions.

As a final real-life example, we would like to share a true story with you. One of us (Roz) was crossing the road with her three-year-old daughter, who suddenly became hysterical and started crying in pain. She showed her mother her hand, which was red, and the child assumed it was blood. She was anxious, crying and seemingly in pain. Once safely on the other side of the road, she and her mother examined her hand and saw that it was not blood, but red ink. The crying immediately stopped, the anxiety stopped and the pain disappeared. The child had been given an alternative explanation for the redness of her hand, one that was plausible, in keeping with reality and significantly less threatening.

This is not to say that you will never find yourself in situations where there really is a problem, or where there really is some threat to you. At the time of writing this book we are in the middle of an economic downturn, so many people’s jobs are at risk. You may have real problems with your health that need a doctor’s help, for example. If this is the case, then the issue is that you have a problem with your job, or your health. You may well feel anxious, but if it is appropriate to the situation, then the way to move forward is to tackle the problem itself. If the problem gets better, so will your anxiety. With an anxiety problem, however, the situation is more complicated. Your anxiety may be out of all proportion to the problem, and your interpretations of the situation magnify it and make it difficult to tackle the problem. Even if you can tackle it, the anxiety may carry on long after the problem has been solved.

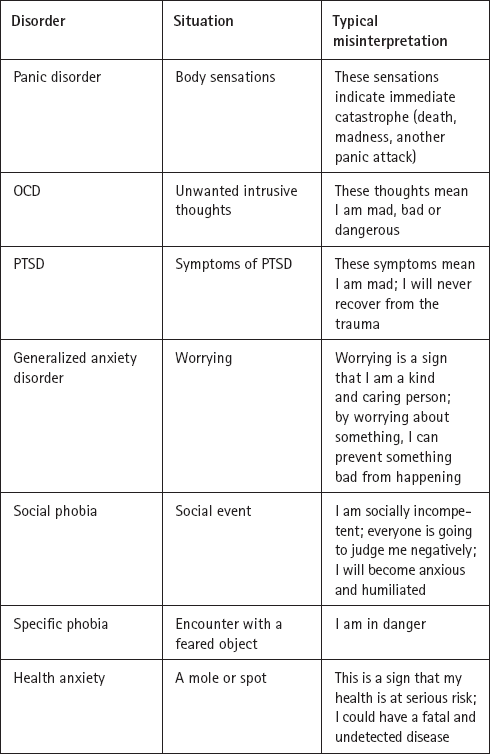

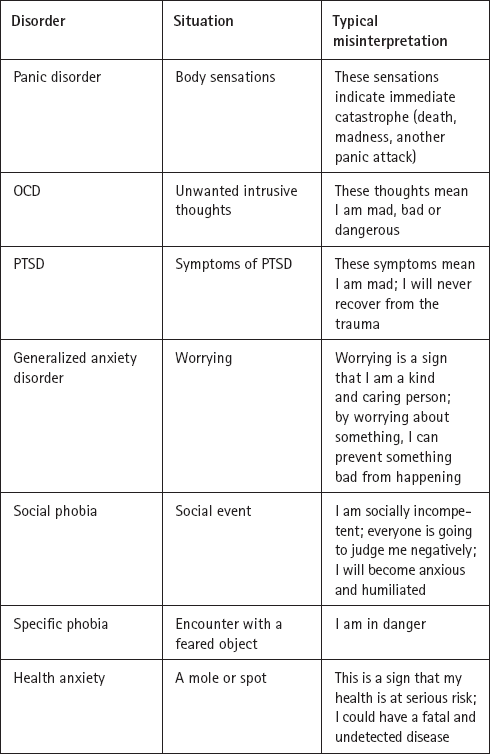

All the cognitive behavioural treatments are based on the view that you are interpreting events as more threatening than they really are, but the content of interpretations differs from disorder to disorder. There is usually a particular kind of situation that is likely to provoke anxiety, and a typical way of interpreting it that is central to that particular disorder. In panic disorder for example, the threat comes from your body sensations, such as feeling your heart beat faster than usual. Although the sensation is ‘normal’ or ‘natural’ or ‘harmless’ (your heart is beating faster because you have just walked up a steep flight of stairs or are anxious), you interpret it to mean that you are about to have a heart attack, or die, or lose control. As a result you start to feel intensely anxious. In social anxiety, the threat comes from a fear of being judged in a negative way – for instance, that other people may see you as boring or stupid. If you are socially anxious you might interpret something that is completely innocuous – someone yawning because they are tired, for example – as evidence that they do think you are boring and stupid.

In both of these examples, the situation was benign – that is, there was no real threat to you, but because you are anxious, you believed that the situation was threatening, and became more anxious as a result.

We often use the term ‘misinterpretations’ for times when your understanding, or interpretation, of what is going on is due to your anxiety rather than the objective threat of the situation.

A list of the typical misinterpretations for each anxiety disorder is shown in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Typical misinterpretations in different anxiety disorders

You may be thinking, what if there is real danger? As we said earlier, you could be in a situation where your interpretation was in keeping with the reality of the situation, and so the anxiety was well founded. If this is so, we would not be talking about an anxiety problem, but about a real-life problem that needs to be addressed. It is when your view of situations, and your consequent anxiety, is out of proportion that we talk about ‘misinterpretation’.

If you can accept that your way of thinking is a fundamental part of the problem, and that your interpretation of events is not ‘the truth’ but a misinterpretation, then you have made a vital step in beginning to change your anxiety. There may be a part of you that accepts this may be the case (maybe your head) but another part of you (perhaps your heart) that does not accept that the problem is one related to how you think. Many people with anxiety problems struggle with this at first, but if you truly can accept that there is no real danger, just your misinterpretation, then you are beginning to make the change necessary to recover from your anxiety disorder. The goal of CBT is to help you reach the conclusion that the problem is one of your thinking and behaviour, rather than that you are, for example, dying from heart palpitations (panic disorder), your thoughts mean you’re bad (OCD), or people will judge you negatively (social phobia).

The first step in helping your head and heart reach this conclusion that applies to all anxiety problems is distinguishing between whether the problem is a real one (you really have a fatal disease) or one of worry (you are worried you have a fatal disease). This has been described by Professor Paul Salkovskis as ‘Theory A vs Theory B’ (Salkovskis, 1996). Theory A (your current theory) is that you are vulnerable to dying (panic disorder), you’re bad for having these thoughts (OCD) or that you’re boring (social phobia). Theory B (an alternative theory) is that you are worried that you are vulnerable to dying, that you’re bad for having these thoughts, or that you’re boring. In other words, Theory A is ‘the truth’ whereas Theory B is that you are worrying about these situations. If you can accept that the problem is your worry, then it follows that we have to understand what is keeping your worry going and what is at the heart of why you are misinterpreting harmless events in this way.

We know that when people become anxious – for whatever reason – the way they process information changes. When you feel anxious your brain starts to see everything through ‘anxious lenses’ without you even realizing that it’s doing it. It is because you are seeing situations in an anxiety-related, threatening way, you feel even more anxious.

When you are anxious, you tend to process information differently and in rather biased ways. We have already spoken about the way in which you interpret events and situations around you in a very anxious way. Another significant factor is that you may find your attention is biased. You become attuned to the possibility there may be some danger or threat nearby, so you start to keep a close look-out for potential sources of harm. We sometimes call this bias of attention being ‘hypervigilant’ for danger. For example, imagine that you have been beaten up once and are scared of being attacked again. You are walking down the street with your friend who is not at all anxious about being attacked. You will find that you notice events that your friend does not – someone down a side road who looks a bit suspicious, or a car slowing down by you on the kerb.

Both these biased ways of thinking – your interpretations and your attention – occur automatically, and an important part of the role of CBT is to help make you aware of them so you can think in a more balanced way.

The box below outlines a number of common cognitive errors as described by Aaron T. Beck in the 1970s and others such as Judy Beck. The error that is most important in anxiety is ‘catastrophizing’, and we will come back to this often in Part 1 and the rest of this book.

Cognitive errors

Catastrophizing

You blow events out of proportion, so that you think that a small mistake or problem will have devastating consequences, completely out of proportion to the reality of the situation.

Overgeneralizing

You make too much of situations. For example, if you make a mistake with a small part of a report at work you might think that it means you are rubbish at your job. If you overcook the rice, you would think it means you’re a terrible cook!

Black and white thinking

You tend to see things as either completely good or completely bad. It means that if something isn’t absolutely brilliant then it must be absolutely awful. The fact that situations normally aren’t brilliant means that you spend most of your time thinking that they’re awful.

Mind reading

This is a problem in all sorts of anxiety problems, but particularly in social anxiety. You think that you know what other people are thinking about you, and you normally think it’s bad! You then react as if your mind reading were the truth, when in fact it’s just what you think someone is thinking.

You imagine what could happen in the future, and then respond emotionally as if these actually are going to happen. For instance, if you are frightened of spiders and tell yourself that there could be one in your bed that night you will be anxious, even though it hasn’t happened.

Discounting the positive

You find ways of dismissing things that don’t fit with your anxious view. You tend to ignore evidence that doesn’t fit, or come up with arguments to say it doesn’t count. For example, if you are socially anxious and someone starts chatting to you during your coffee break at work, you might think, ‘They’re only doing it because they feel sorry for me’, rather than thinking it’s because they want to. Discounting the positive means that it’s easier to hang on to your anxious interpretations.

Filtering

You see only the bad and ignore the good. You see your problems and weaknesses, but disregard your strengths and your accomplishments.

Labelling

You tend to apply simple, and often personal, labels to explain events that happen. For instance, if you weren’t given a promotion at work you might tell yourself it was because you’re a ‘loser’ or you’re ‘pathetic’, rather than thinking it was because the person who was promoted had five years’ more experience than you. You might tell yourself that other people are mean or that the world is a bad place. These labels then make you feel more inadequate and anxious.

Stefan was putting up a shelf in a client’s house when he realised that the wood that he’d used had a lot of knots. He thought, ‘Oh no, that looks dreadful; my employers are so perfectionist they’re going to be really furious. They’ll sack me, and won’t recommend me to their friends, and I’ll never get more work. We’ll lose the house; we’ll end up homeless.’ This was clearly a catastrophic misinterpretation. As a result of this misinterpretation he understandably felt anxious, and found it hard to concentrate on what he was doing for the rest of the day. Later in the evening when he spoke to Magda, she said, ‘I think you’ve blown it all out of proportion! I thought that you told me that your employers liked ethnic wood; they’ll love the knots. Anyway, even if they don’t you could always change it. We’re not going to lose the house because of one shelf!’ Magda helped Stefan to see the difference between real and hypothetical worry about the knots. The real worry was that his employer might not like them. The hypothetical worry was that he’d be fired.

Nicky’s misinterpretations

Nicky was out for a meal with friends when she realized that they were about to serve her chicken. (Remember that she had nearly suffocated when a chicken bone got stuck in her throat at the family barbecue.) She thought, ‘Oh no, I can’t eat chicken. What if it has bones in it? What if I choke again?’ She started to feel very frightened, and then she noticed that she couldn’t breathe properly, and she started to feel like she was suffocating. She thought, ‘I can’t breathe, I’m suffocating, I’m going to die.’ Not surprisingly, she felt extremely anxious. Like Stefan, she was showing very clear catastrophizing – in other words she was expecting the absolute worst – thinking that changes in her breathing meant that she was going to suffocate and die. In fact, it is common for people to experience difficulties in their breathing when they get a bit anxious, and so a more accurate interpretation might be: ‘Oh, I’m breathing too fast. I had better try to slow my breathing down and then it’ll feel better.’

Tips for supporters

• Do all you can to try to help the person you are supporting see that it is reasonable to consider that the problem is their way of thinking. Help them to see that it therefore follows that what they have to do is to examine this and, ultimately, to change it.

• If you know them well, try to find examples of misinterpretation in their lives – perhaps when they might have misinterpreted something and then seen it in a different way later. Try using questions like ‘What would you say to a friend who thought like that?’