I wake up in the morning worrying; I go to sleep at night worrying. I feel like my head is going to explode!

Pieter, 18

I know people think I’m being stupid but I can’t bear anything to do with spiders. I can’t let the children play outside in case they come home with a spider on them, and I have to check all the bedrooms before we go to bed to make sure there’s nothing there. Just thinking about spiders makes me break out into a sweat.

Mary, 37

I know everyone gets worried about talking in meetings, but I get so anxious that I can’t even go to them. I’m sure everyone will think I’m stupid and pathetic if I talk, but I keep making such feeble excuses that they probably think that anyway now.

Kai, 28

I keep getting stomach aches, and every time they start I think, ‘That’s it, I know I’ve got cancer.’ I spend my whole time feeling my stomach to see if I can feel lumps growing. My doctor says there’s nothing wrong, but I just don’t believe her.

Jane, 43

Feeling anxious is undoubtedly a fact of life, and there are few of us who could say that we have never experienced any problems with it. Many of us feel nervous before job interviews, or get butterflies in our stomach at the top of tall buildings or steep cliffs. Sometimes anxiety can be ‘normal’ in the sense that it fits the occasion, but it can also be ‘abnormal’ – that is, the anxiety starts to take over our thinking processes and our lives, and makes it difficult for us to function.

If you think about the last time you were anxious it is likely that you experienced a number of different thoughts and feelings. You might have felt your heart beating fast, your breathing speeding up, your palms becoming sweaty. You might have noticed that you were thinking, ‘Oh no – something terrible is going to happen. I must get out.’ You might have had a great sense of fear, and a strong desire to get out of the situation.

The two stories below describe two people who experience very different kinds of anxiety. We will come back to them throughout Part 1 of this book.

Nicky: Nicky is a 19-year-old woman from a sporty family, all of whom are physically fit, and Nicky is very athletic. She is the youngest child and the only girl. Her older brothers have always teased her about being less strong than them. No one in their family is ever ill, and they are proud of how fit they are. The family was having a barbecue in the summer when a chicken bone got lodged in Nicky’s throat and she nearly suffocated. She remembers the horrible feeling of not being able to breathe. It became so serious that her friend had to do the Heimlich manoeuvre on her to dislodge the bone. Since then she has become frightened about eating in case it happens again. She has to check everything that she is going to eat very carefully to make sure there are no bones or lumps that could catch in her throat. She has also started to get out of breath for no reason – she just starts feeling breathless out of the blue. When this happens she can feel her heart pounding and she breaks out into a sweat. She becomes terrified that she’ll die and becomes overwhelmed with anxiety. She also has nightmares about the barbecue experience and wakes up in a cold sweat. Her brothers are now teasing her a lot more – they don’t realize how serious it is – and she has to leave the room if she thinks they’re going to start talking about her fears.

Stefan: Stefan is a 31-year-old builder and decorator from the Czech Republic who has a wife and two children in his home country. He came to England because he could not find work at home. He comes over for a few weeks at a time. He works ten–twelve hours a day, and spends very little money, so that he can take most of what he earns back to his family. He is pleasant, speaks English well, and works hard, so people are happy to recommend him to their friends, but the change in the exchange rate and the economic downturn mean that the jobs are drying up. Meantime, his wife is now pregnant again. He is worried that he won’t be able to support his family and they’ll have to leave their home. He is tense and can’t sleep well at night, because he is worrying about what the future holds. He has always been confident about his skills, but now thinks everything he does is full of mistakes, and is afraid people will stop recommending him. He misses his young children, and feels sad and guilty that he is away from home so much. He is starting to feel low and struggles to keep going at work; he gets irritable and snappy when things go wrong.

Almost everyone has experienced anxiety at some time in their lives, and to do so is not only natural, but also sensible. The box below explains why.

Fight or flight

To understand why we’re designed to feel anxious from time to time, we need to go back a few hundred thousand years! When humans were evolving they lived in tough environments, and had some tough competitors – including each other – for food and shelter. Most of the situations that were dangerous involved physical threat – the sabre-toothed tiger stalking people as food, the younger man about to take over the prime position in the tribe – so humans developed a response known as the ‘fight-or-flight’ response. This means that the moment that we sense danger our bodies act quickly to prepare us to tackle it. Adrenalin and other hormones are released that result in physiological changes – for example, our heart beats faster in order to pump more oxygen around our bodies. These changes mean that we are primed to be as strong and as quick as we can be, so that we can fight our enemy, or get out of the situation fast. We undergo some psychological changes, too – we become intensely aware of things around us that might be dangerous and we react quickly. This is sensible as well – if a sabre-toothed tiger is about to spring it probably isn’t sensible to think, ‘Hmm . . . I wonder if he’ll attack me – how’s he looking? What do you think?’ It’s more sensible to get out and think later.

There is another aspect of our evolutionary response to anxiety that gets talked about less, and that is the ‘freeze’ response. As many people will know, particularly if you have watched Jurassic Park, the vision of predator animals is attuned to movement. Their vision is less accurate for stationary objects. If you are in a situation when fighting or running away isn’t going to be much help, your body freezes – much like a rabbit caught in car headlights – so that you stay absolutely still and can’t be seen.

The problem with the fight-or-flight response is that many of the situations that we now face don’t require a physical response. When you sit down to revise for an exam feeling nervous, it’s really not that much help if your body is in full swing for action. The racing heart and increased strength in your muscles aren’t needed in that situation and can make you feel more tense. Freezing is not much use either, particularly if you find that your mind freezes as well and you can’t even think.

So anxiety is in fact a useful development for us – it makes us react to dangerous situations quickly, and it gears our bodies up to make sure that we are as strong and fast as possible. In modern life, however, this primitive survival mechanism can be less useful than in times past, and makes life more difficult.

Throughout the book we talk about danger and threat, so it might be helpful to explain what we mean. As the fight-or-flight description explains, ‘danger’ at its simplest means immediate physical danger – like the danger of being attacked. Danger also has a wider meaning – you might be in ‘danger’ of losing your job, or of people laughing at you if you stammer. Any situation in which you might come to harm is threatening, even if the harm is social or psychological rather than physical, could be described as dangerous.

This is similar to ‘threat’, which describes any situation in which you might come to harm. In theory ‘threat’ refers to situations in which there is a possibility rather than a certainty of harm, but in practice ‘danger’ and ‘threat’ are often used interchangeably.

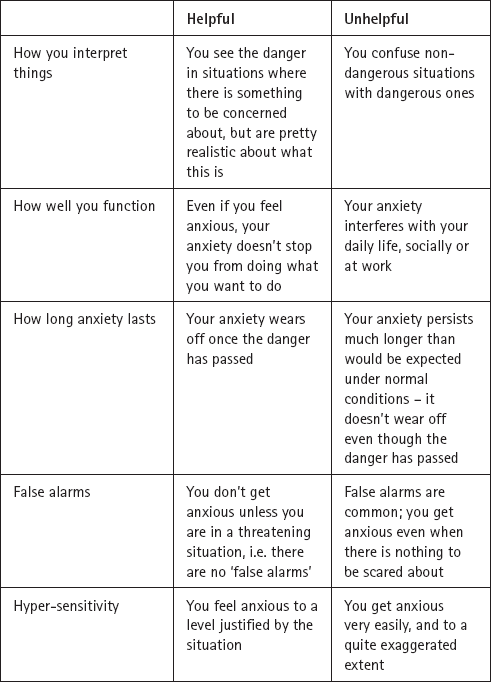

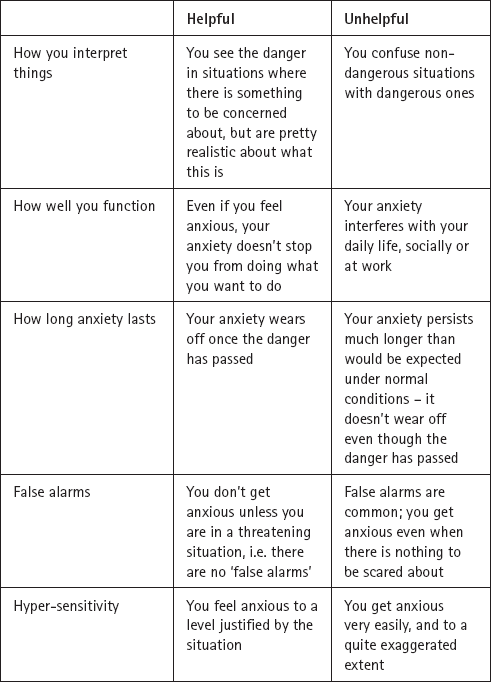

It would be odd if we never experienced any anxiety at all, but anxiety can become a problem in two ways. Firstly, you may find that you become anxious when there is no real danger – but to you it seems as though there is. Secondly, you may find that you become anxious in the sort of situation where most people would feel a bit nervous, but that your anxiety is more marked and excessive. Table 1.1 below shows five important differences between helpful and unhelpful anxiety (adapted from a book by Clark and Beck, published in 2010).

It may be more useful to think about unhelpful anxiety as being on a continuum or a scale – that is, anxiety could be a mild problem, or a moderate one, or a severe one. At the point where you are feeling anxious and distressed a lot of the time, and anxiety is dominating your life, dictating what you can and can’t do, then we would say that you have developed an anxiety disorder.

Table 1.1: Helpful and unhelpful anxiety

Adapted from Cognitive Therapy of Anxiety Disorders: Science and Practice, D.A. Clark and A.T. Beck, (2010). Copyright Guilford Press, New York. Adapted with permission of The Guilford Press.

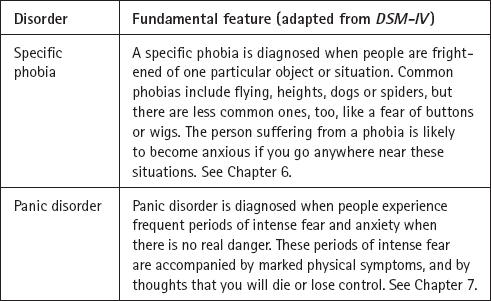

So far we have spoken about anxiety as if it is just one kind of problem, but there are many different types of anxiety disorder. There are two commonly used systems of classifying disorders, the American Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-IV as it is known, and the one used by the World Health Organization, the International Classification of Diseases or ICD. These classificatory systems are shortly due to change and DSM-V will soon be published by the American Psychiatric Association. Only a trained mental-health professional can diagnose you as having a particular mental-health disorder. However, there are questionnaires and checklists published by various bodies, including the American Psychiatric Association and the World Health Organization that may help you assess yourself.

These two systems aren’t identical, but they do overlap considerably. The main anxiety disorders are the ones listed in Table 1.2 below, which also gives a brief description of each of them. We have included health anxiety although it is not formally classified as an anxiety disorder. These are the anxiety disorders covered in this book, and each of the chapters that follow this introduction contains an in-depth description of a specific problem.

Table 1.2: Symptoms of specific anxiety disorders

Table 1.2 above describes the different symptoms of these specific anxiety problems. It is also important, however, to remember that anxiety disorders have a lot of symptoms in common. These common symptoms are shown in Table 1.3 below.

Table 1.3: Symptoms characteristic of most anxiety disorders

Eventually Nicky’s anxiety got so bad that she decided to seek help. After she spoke to her GP she was assigned to a psychological well-being practitioner (PWP) to assist with her self-help. When Nicky was told about the symptoms of different anxiety disorders she immediately recognized that she was having panic attacks. She had episodes when she felt intensely frightened and was convinced she was going to choke, and these had started to happen out of the blue, even if she wasn’t eating anything. She also realized that she had some mild symptoms of OCD – she spent a long time checking her food to make sure that it was OK before she could eat anything at all. She also had some symptoms of PTSD – at the barbecue she had seriously thought that she would die, and she was still having nightmares about it, and couldn’t stand it when her brothers reminded her about the event.

Stefan’s story

When he went home Stefan talked to his wife, Magda, about how he had been feeling. She was really sympathetic and they decided that he should start trying to do something about it. When he looked up his symptoms he thought that he probably had generalized anxiety disorder, or GAD. He was worrying about a lot of different things – his work, his finances, his family – and had many of the symptoms, particularly being tense and anxious and finding it hard to sleep. He decided that he would try to tackle this himself with Magda’s help.

In some ways, what you label your anxiety disorder may not seem important but because the different treatments for the anxiety disorders have been developed for specific forms of anxiety disorder, it is important to identify your anxiety problem correctly. Table 1.2 may not provide enough information, in which case use the flow chart on the following pages to help (adapted from www.iapt.nhs.uk – http://www.iapt.nhs.uk/silo/files/the-iapt-data-handbook-appendices-v2.pdf (Appendix C, page 20).

Having identified the exact nature of your anxiety problem, you will know what anxiety disorder(s) you may have and which chapters in this book you should read. Rather than simply jumping to them straight away, we suggest you read through Part 1 first, which gives you information about how cognitive behavioural therapy is structured and how to get the most from the different chapters that follow.

We have seen that anxiety disorders have shared symptoms, and a lot of people have more than one type of anxiety problem. Because of these common factors, it is not surprising that the treatments for the different anxiety disorders have a lot in common – often they are trying to tackle the same problem. You will see later on that the methods outlined in Part 1 are designed to help address these common symptoms. People with panic disorder often worry excessively about real things (as in people with generalized anxiety disorder). People with obsessive compulsive disorder also worry a great deal, have panic attacks, and often are socially anxious as well. It is this overlap in symptoms that partially explains why cognitive behavioural therapy for the different anxiety disorders has so many things in common – the treatment is trying to change similar problems. But it is by concentrating on the ‘pure’ forms of the disorders – that is, when people only have one problem – that researchers have been able to understand them, and develop effective treatments.

The answer to whether it makes sense to classify the disorders is both Yes and No. Yes, because the classification tells us something about the key features of that particular problem, what sustains it and how best to treat it, and No because the disorders have so many features that overlap. Despite this confusion, it remains the convention to classify anxiety into this or that type of disorder, and for the purposes of this book this is a convention to which we will adhere.

We hope you have now been able to think about what form of anxiety disorder is most relevant to you, and we will show you how to overcome it, using ideas from both Part 1 and the individual self-help programmes in Part 2.

Tip for supporters

If you want to help the person you are supporting to find out more information about the different disorders, look at the individual chapters and also look up the different problems directly by finding the criteria used by ICD-10 or DSM-IV on the internet. You could help them to find this guidance rather than letting them seek it on their own so that they don’t feel overwhelmed.