6

QUEBEC, September 7, 1775

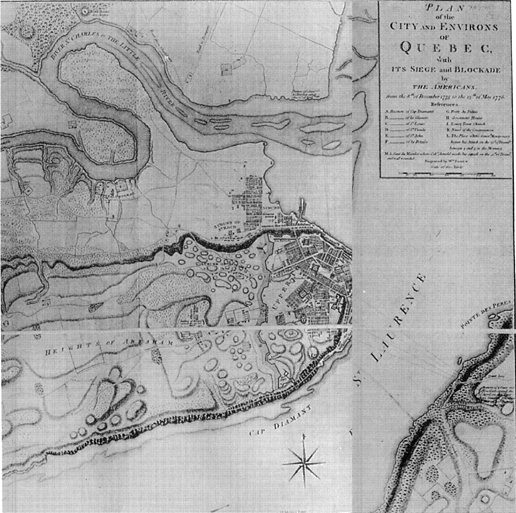

From the west, the direction from which the express rider approached the city, most of Quebec lay hidden. For it was built on the side of a cliff facing east at the narrow points where the St. Charles River flowed down from the north to mingle with the waters of the great St. Lawrence. It peered, as it were, over the high plateau called the Plains of Abraham while the body of the town was covered by the rock face.1

High walls encircled the Upper Town protectively, reaching from the lofty crag of Cape Diamond, which overlooked the St. Lawrence on the south, to the bank of the St. Charles, near Quebec’s little port to the north.

It was a fortress city—gaunt, cold, but brilliantly sited for defense. It was from here that Britain ruled Canada, the vast province that, with the help of its American colonists, it had wrested from the French a decade and a half ago.

Dominating the upper part of the city was the formal residence of the royal governor, Sir Guy Carleton, the Chateau St. Louis, a magnificent building featuring the tall, pointed towers favored by French architects.

To the chateau news was rushed that day that the rebels had invaded Canada in force, sweeping along the Richelieu River from Lake Champlain to the little town of St. Johns. St. Johns was the northernmost point ships could reach, for from there the river fell sharply in rapids and waterfalls for 10 miles to Chambly before flowing on into the St. Lawrence.

It was no surprise to Carleton. He had been doing what he could to prepare for it for months—ever since the morning in May when, after the fall of Ticonderoga, two big American raiding parties had swooped on the Richelieu. They had been led, so Carleton had reported disdainfully to London, by Benedict Arnold, “said to be a native of Connecticut and a horse jockey,” and Ethan Allen, “said to be outlawed in New York.”

They had stayed only to raid some British stores in the town and to capture two vessels, moored on the river; then they had dropped back along Lake Champlain to Crown Point. Arnold had warned the local inhabitants that they would soon return with 5,000 men, and Carleton, who had just heard of the thousands of men who had massed to attack the British troops on the Concord road, did not disbelieve him.

Carleton, a tubby, buoyant, energetic general, was virtually helpless. He was the royal governor of one of the most powerful nations in the world, yet from the start he had known there was little he could do to challenge a major strike by the rebels. For to protect the whole vastness of Canada, he had barely 600 soldiers fit for duty.

Truly, his only hope lay in the Canadians and possibly, as a very small fringe extra, in the Indians for whom Carleton had little regard. In London the Canadians were seen as a potential force of some size, a militia that merely awaited the call. When the first searing reports of the conflict in Massachusetts had reached Whitehall, Dartmouth had sent out prompt orders for 2,000 men to be raised and dispatched the equipment for them by ship. Later he increased the figure to 3,000. It was a typical piece of London planning designed around men who were just not there—at least not there willing to take up arms.

During the previous year, as Carleton discovered very quickly, Samuel Adams’ agents had been moving through the towns on the St. Lawrence, urging the Canadians to form Committees of Correspondence and to send delegates to Congress. They had some ready-made ground support, for the Old Subjects, as the Protestant families of British origin were known, had greatly resented the Quebec Act with its concessions to the Catholics. In January, Carleton had written to Dartmouth that some of the Old Subjects were, with their “cabals and intrigues . . . exerting their utmost endeavours to kindle in the Canadians the spirit that reigns in the province of Massachusetts. . . .” But Canada sent no delegates to Philadelphia.

In theory, the colony seemed a fertile ground for revolution. It was controlled on completely undemocratic lines, with no form of elected assembly in the sense that there was in all the American provinces. But the Catholic Canadians, especially the numerous priest-controlled peasant habitants, were not eager to join forces with a congress of Americans who, in an impassioned letter to the King about the Quebec Act, described their faith as “a religion that has deluged your island with blood and dispersed . . . persecution, murder and rebellion through every part of the world.”

As the tension rose in Boston during the spring, the American agents changed their tactics to combat the stony apathy they encountered in the north. John Brown, a representative of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, on a visit from Massachusetts, warned merchants in a Montreal coffeehouse that “if a man of them dared to take up arms and act against the Bostonians, thirty thousand of them would march into Canada and lay waste the whole country.”

Canada was vital strategically. Under British control, it would form a constant threat to the Revolution, for at any time an army could be thrust quickly down the Richelieu River-Lake Champlain waterway that reached south almost to the Hudson; that was why the British considered it essential for Carleton to hold the province against attack.

Through the summer the governor had done his best. He had fortified the strategic towns where he could. He had tried to rally the Canadians and had succeeded in raising 500 men, though they were not very reliable. He had rushed the construction of a couple of armed schooners at St. Johns—racing with the rebels who he knew were busy on a similar high-speed program along the lake at Crown Point—and dragged up some flatboats, each mounted with one cannon, through the rapids from Chambly.

With some misgivings, he had presided at a conference with the Indians of the Six Nations, for he knew that when Ethan Allen had led his raiding party into the Canadian forest in May, he had contacted the Indians. “George our former King,” Allen had written in a letter that had been duly sent on to the Chateau St. Louis, “has made war . . . and sent his army and they have killed some of your good friends and brothers who lived at Boston. . . . I want your warriors to join with me and my warriors, like brothers, and ambush the regulars. If you will, I will give you money, blankets, tomahawks, knives. . . .”2

Clearly, Carleton had to keep the sympathy of the “savages,” and the British were well placed to do so. Their Indian Department had been dealing with the tribes for years. Thayendanegea, one of the Mohawk chiefs, had even been brought up in the home of the Johnson family, who had run the department for years. Traditionally, Britain had helped the Six Nations of the Iroquois League, whose lands were south of the St. Lawrence, against their enemies.

At the June conference, organized in Montreal by Colonel Guy Johnson, the present department head, each of the assembled tribes was given a war belt. War songs were chanted, and Johnson invited the Indians “to feast on a Bostonian and drink his blood.” The symbolism sounded more bloodthirsty than it was. Carleton refused to exploit this source of savage killers and rejected their offer to lay waste the New England frontier. All he wanted, he said, was to keep a party of forty or fifty braves at St. Johns for scouting, in which role they were unsurpassed. “The Indians,” recorded Colonel Daniel Claus, who was present, “were somewhat disgusted at their offer being rejected,” but they agreed to do what Carleton asked.

The first news of the September invasion to reach the Chateau St. Louis was that a group, consisting mainly of these Indians, had thrown back the first rebel thrust at St. Johns.

With its undertone mockery of the rebel fighting abilities this news made a dramatic highlight for the letter to London, but Carleton knew that he had no resources for anything more than a holding operation.

Leaving Hector Cramahe, the lieutenant governor, in charge of the siege preparations at Quebec, he hurried to Montreal to command his slender defense forces. Within only a short while both the Richelieu towns—St. Johns and Chambly—were under siege, their meager garrisons hopelessly outnumbered. Advance rebel parties under Ethan Allen were at Laprairie, just across the St. Lawrence from Montreal.

The senior rebel commander was Brigadier General Richard Montgomery, a tall competent Irishman, known to Carleton because he had spent most of his life in the British army. In fact, as a boy, Montgomery had taken part in Wolfe’s siege of Quebec.

Carleton had been there, too, and, as he well knew, he would soon be there again, this time on the inside. For his only hope now of retaining any part of Canada was to hold Quebec.

By the third week in September Carleton’s position in Montreal was precarious. Apart from a few Canadians he had persuaded to help, he had only fifty soldiers remaining from other garrisons, to hold a town whose extensive walls were completely inadequate for defense against sustained attack. The Indians had deserted him and made peace with the rebels. Many of the residents of Montreal, while not necessarily favoring the Americans, were sullenly anti-British. When the rebels first appeared at Laprairie, there was a move in the town to offer immediate surrender “to prevent their being pillaged, but,” reported the governor, “they were laughed out of it temporarily.”

Carleton had sent an urgent summons to Boston for troops, but he knew that even if Gage could spare them, the chances of reinforcements arriving in time were slim.

On September 24 there was a rumor that Allen was going to attack that night. Carleton issued orders that surburban residents who owned ladders should lodge them within the walls, but he was flagrantly disobeyed.

Early the next morning an advance guard of the rebels crossed the river. In the town, the drums hammered out the alarm. “All the old gentlemen and better sort of citizens . . . turned out under arms,” reported Carleton.

A polyglot force of 200 marched out of the town to attack the marauders. To their surprise, they captured Allen with 35 of his men.

For Carleton, desperate for any kind of victory to rally the Canadians, Ethan Allen was an important prize. He sent him down the river to Quebec to be shipped to England as soon as possible. But basically it did not alter the situation of the British. The only checks on the rebels were the besieged posts on the Richelieu.

On October 19, after a couple of American flatboats had made a perilous descent through the rapids from St. Johns with some 9-pound cannon, the rebels opened fire on Chambly. The walls were not strong enough to withstand cannon shot, and the end came fast.

St. Johns was now completely isolated. In one last wild emergency move, Carleton tried to launch a big enough force onto the south bank of the St. Lawrence to make a push south to relieve the town. He ordered Colonel Allan Maclean, who had raised a small force of loyal Scottish immigrants, to approach from Quebec and advance up the Richelieu. Simultaneously he himself led an assault across the water to Laprairie.

The rebels fought back fiercely. Their guns bombarded the assault craft and forced the flotilla to turn back to Montreal. Maclean, too, was badly savaged. Canadians he had pressed into service refused to fight. He fell back to his boats and retreated down the St. Lawrence.

St. Johns held out for a few more days until, on November 2, the garrison surrendered.

Now that there was nothing to divert the rebels from Montreal, Carleton knew he could not hold the town. “It is obvious that as soon as the rebels appear outside the town in force,” he wrote home, “the townspeople will give it up on the best terms they can procure. I shall try to retire the evil hour . . . though all my hopes of succour now begin to vanish.”

Hurriedly, he made plans to escape with his soldiers and supplies to his last post in Canada—Quebec. Anchored in the St. Lawrence, off Montreal, he had eleven ships3 of varying sizes. Their captains were ordered to prepare for the run down the river that was certain to be strongly challenged.

Meanwhile, at Quebec, Lieutenant Governor Hector Cramahe, an anxious civil servant with no experience as a soldier, was supervising the final preparations for the defense of the town that had been in progress for several weeks now. The walls had been repaired. Lanterns, attached to long poles, lay ready on the ramparts to illuminate the approaches in case of night attack. Four merchant ships had been fitted out with cannon. During the past few days, two royal naval vessels, the sloop Hunter and the Lizard frigate,4 had arrived at Quebec, and Cramahe had eagerly taken the Lizard’s thirty-five marines to supplement his tiny defense force.

Since Maclean had gone up the river to help Carleton with his last-minute attempt to relieve St. Johns, there were no British soldiers in the town at all. The defense of the walls was in the hands of volunteer Irish fishermen and a highly suspect militia. In addition, many of the citizens of Quebec were openly favorable to the rebel cause.

The prospects for Quebec were never good. But on November 3, while Carleton was in Montreal planning his evacuation, they grew drastically worse. News reached the Chateau St. Louis of an enormous threat from a new and entirely unexpected direction. Cramahe was handed a letter taken from an Indian messenger addressed to a Quebec merchant named John Mercier.5 It was from Benedict Arnold and revealed, to the lieutenant governor’s appalled astonishment, that at the time he wrote the letter the American colonel was at Dead River on his way north with a force of “2,000 men . . . to restore liberty to our brethren of Canada.”

Dead River was south of Quebec in the vast rugged wilderness of present-day Maine. The implications of the news were almost incredible. For they meant that Arnold and his army would be advancing on Quebec from country that in November, when Canada and northern New England were already snowbound, the British regarded as impassable.

In fact, as Cramahe must have realized when he studied his maps and consulted his Canadian advisers, Arnold had traveled by an old Indian route—up the Kennebec, a long river whose churning waters tumbled down to the Atlantic from the forested highlands of Maine over endless falls and rapids and every kind of human obstacle. High up the river they had carried their boats and equipment 12 miles to Dead River, along which they could move north for 30 miles before they again had to lug their transport and baggage overland to a stream that flowed into Lake Megantic and linked with the Chaudière River.

The waters of the Chaudiere streamed into the St. Lawrence only four miles from Quebec. For Indians in the summer with light canoes, the route was not too difficult; but for an army of nonwoodsmen, laden with equipment, in the late fall, it was a fantastic journey to attempt.

Fantastic or not, reports from the villages on the Chaudiere soon confirmed the truth. It was an incredible achievement in leadership by a man who soon became something very close to a legend. Every war produces its blood-and-guts commanders, but thirty-four-year-old Arnold, as the British were soon to learn and eventually exploit, combined an impassioned personal dynamism with great intelligence. Thickset, swarthy, with immense physical strength, he was a superb and daring tactician.

Brought up in one of Connecticut’s richest families, he was an entrepreneur businessman who, in addition to other ventures, had made a great deal of money out of shipping horses from Canada to the West Indian sugar plantations.

By that winter the British in Canada knew very little about him except for his vague connection with horses. But the news of his advance out of the rugged backcountry of Maine at a time when they were so vulnerable was enough for Cramahe to order all canoes and small craft across the St. Lawrence from the south bank. On November 9, just six days after the rebel leader’s letter had arrived in the chateau, American advance troops appeared at Point Levis across the river from Quebec.

By then Colonel Maclean was on his way back along the 120-mile stretch of river from the Richelieu to Quebec with the eighty men he had been able to extricate from the force he had taken down to join Carleton. On the journey downriver, he was approached by a boat moving upstream; on board, with dispatches from Arnold, was an Indian who assumed that the returning British were advancing Americans. 6

From Arnold’s own letter to Montgomery, Maclean learned the story of his incredible journey. “We have hauled our bateaux over falls, up rapid streams . . . and marched through morasses, thick woods and over mountains about 320 miles. . . .”

Arnold had been warned by his scouts that Cramahe had stripped the south shore of the river of small craft, but Indians had joined him with twenty canoes that could be used as transports. “I think the city must fall into our hands,” he had written.

Maclean hurried on toward Quebec into a gale-force easterly wind that churned the broad waters of the river. It was far too rough for canoes, and when Maclean’s boats heaved and wallowed their way into Quebec’s little harbor on the night of the eleventh, Arnold’s men still waited on the south bank.

Gratefully Cramahe, the civilian, handed over the military command of the town to Maclean, who formed immediate plans to attack Arnold as soon as he tried to make the three-mile river crossing. Armed naval vessels sailed out of the harbor into the open choppy waters and took up station: three of them along the north shore to head off the rebels as they tried to land; one, the Gaspe brigantine, scanning the south bank for signs of their departure.

On November 13 the gale blew itself out. That night, despite the British ships and the small craft that patrolled between them, Arnold and his men slipped across the river, landed at Wolfe’s Cove and climbed the cliffs—now made easier with a path—up which Howe had led the celebrated assault sixteen years before onto the Plains of Abraham. By the time one of the patrol boats detected them they had almost completed landing on the north shore. As the boat approached to investigate, the rebels opened fire, and it veered away sharply to carry the alarm to the Lizard, the frigate anchored off the town.

That morning the rebels advanced to within 800 yards of the city and gave three great cheers. They were a ragged lot. Bearded, with their tow-cloth hunting shirts torn, many of them had no hats and, instead of boots, wore moccasins made from raw skins. As one of them, Abner Stocking, recorded later: “We much resembled the animals which inhabit New Spain, called the Ourang-Outang.”

However, to the men at the guns watching them from the walls they seemed formidable enough. They put their matches to the touchholes of the 24-pounders, loaded with antipersonnel grape and canister shot, the guns flashed, the explosions following each other loudly in quick uneven succession. For a few seconds smoke obscured the view from the ramparts; then, as it cleared, the artillerymen saw the rebels dropping back.

Later in the day, Arnold sent a letter to the town under a flag of truce demanding surrender “in the name of the united colonies.” He warned: “If I am obliged to carry the town by storm, you may expect every severity practised on such occasions and the merchants who may now save their property will probably be involved in the general ruin.”

During those critical hours, as they waited for Arnold to attack, the situation of Quebec seemed very grave. There was now little hope of reinforcements. Howe had refused a second urgent call for help to Boston because of the dangers to relief ships at that time of year. Although vessels could still just get through, very soon the thick ice would block the sea approach to the St. Lawrence and the town would be sealed off from England until the spring.

Arnold, however, would soon be strongly supported. With Montreal on the point of surrender, before long Montgomery’s army with its guns would be advancing up the river to join the besiegers. In addition, the rebels had many sympathizers in the town; an internal attack was a strong possibility.

Cramahe summoned a council of war in the Chateau St. Louis to decide policy—Maclean, the captains of the naval ships, the masters of some of the cargo vessels, the colonels of the militia and the town mayor.

The anxious men in the big room in the gloomy chateau must have been only too conscious that General Montcalm had presided over a similar conference sixteen years before. But then it was the British who were outside the walls. The French, however, had been in Quebec in some strength; Montcalm had regular soldiers to defend the town. Now Maclean had only a handful of trained men: thirty-five marines, one or two gunners and a few fusiliers. In addition, he had his Royal Highland Emigrant Regiment, which he had recruited in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland in the summer, but they had been under arms only a few weeks.

The truth was that if the town was to be held, the main brunt was going to fall on civilians—merchants, civil servants, sailors and fishermen. The walls were long, and though they had guns to fight off attack, they had very few experienced gunners. Crudely tutored civilians would have to handle the big cannon—highly dangerous to the gun teams, unless handled with precise care.

On the other hand, Quebec was a fortress that had never been taken by storm. Montcalm’s fatal error had been to march out from behind his strong protection and fight the British in straight combat. There was enough food in the city to last until the spring and adequate ammunition—if the amateur garrison could only succeed in firing it.

The war council decided to fight, to hold Quebec to “the last extremity.” All surburban houses that were close outside the walls and could provide cover to the besiegers were to be destroyed.

An embargo had already been placed on all vessels in the port—except for the ships bound for Britain with the valuable cargoes of furs—and the crews recruited for defense.

There was still just time for a ship to get through to the Atlantic before the ice closed in. It was decided that a naval officer would be sent to Britain to describe the exact situation; pilots would go with him to bring in the relief forces on the off chance, which seemed remote at the moment, that the garrison could hold out until the ice melted. A secret signal—a blue pennant over a Union Jack and the firing of five guns—would inform an approaching fleet that the ships that remained and the city itself were still in British hands.

For four days after they paraded in front of the walls on the Plains of Abraham, Arnold’s tattered army quartered in nearby houses besieged the town. Then, on the eighteenth, the men on duty on the walls saw them trailing west across the snow in a long and ragged column. Reports came in that they had withdrawn to Pointe aux Trembles, 20 miles up the St. Lawrence, to wait for Montgomery.

Arnold, so the British learned too late, had been warned that Maclean was planning an attack from the town to coincide with an assault on his rear from two armed ships that were rumored to be on their way down the St. Lawrence with 200 British troops. He was retreating, according to reports that streamed into the town, only to wait until Montgomery joined him with cannon; then the combined rebel force would storm the town.

The rebels were better informed about the crisis situation in Montreal than the British. By the nineteenth there was still no news of Carleton in Montreal, but reports had arrived in Quebec of American plans to stop his escape. At Sorel, where the Berthier Islands split the waters of the St. Lawrence into narrow rocky streams, the rebels had set up batteries of guns.

Eight days earlier, on November 11, Carleton had been warned that Montgomery’s main force was approaching Laprairie on the far side of the river. He ordered the planned evacuation. At dusk, his eleven ships, loaded with ammunition, supplies and more than 100 fighting men, weighed anchor and moved down the St. Lawrence under fire from rebel guns on the south shore.

The next day one of the ships ran aground, and the little fleet had to heave to until it could be cleared. Then that night the easterly gale that had held Arnold down opposite Quebec roared up the river past Sorel. The British vessels had no alternative but to drop anchor and ride out the storm. But Carleton’s luck was out. On the sixteenth, five days after they had left Montreal, the wind was still in the east. Until it veered west, they would have no hope of making their gauntlet run through the long narrows at Sorel—with rebel guns pounding them at close range from both sides.

At last, Carleton decided he should go on ahead and try to escape past the rebels so that he could take command in Quebec. He sought the help of Captain Bouchette, master of one of the merchant ships in his flotilla, who was nicknamed La Tourte (the pigeon), owing to his reputation for fast sailing.

That night Carleton, disguised in the clothes of a Canadian peasant habitant, clambered down into a whaler7 commanded by the captain. The oars were muffled to hide the noise of wood on wood in the rowlocks; signals to be passed by touch from man to man had been agreed on so that complete silence could be maintained.

The whaler pushed off quietly down the river. It was a dark night under a clouded sky, and by staying in the middle of the broad river, they were in little danger until they reached the narrows of the Berthier Islands where the rebels had set up their gun batteries.

As they approached the dark bulk of the islands, with the oars slipping quietly in and out of the water, they could see the American bivouacs along the bank. Blazing fires lit up whole areas of the stream. As they passed into the flickering pools of illumination cast by the flames, the oarsmen stopped rowing and crouched down, drifting with the current, which on the St. Lawrence ran very fast, so that the boat resembled one of the big hunks of rotten timber that were always floating down toward the sea.

For nine miles they went on through the narrows, holding their position in the stream by paddling with their hands. All the way down, they could hear the routine challenges of the sentries and the barking of the camp dogs.

Then, at last, they were through the islands—and out in the wide waters of Lake St. Peter, which balloons the St. Lawrence at that point.

The town of Three Rivers lay near the head of the 30-mile lake. Not far beyond it, they found at anchor a British armed brig which took them the rest of the way to Quebec.8

At Quebec, Carleton still seemed to hope that there was just a chance that some of his ships, at least, might get through the narrows of the Berthier Islands when the wind changed. “The seamen tell me that the wind was fair for passing by Sorel last night, yesterday and the night before,” he wrote to London on the twentieth with an optimism that must have been forced.

By then the fleet had been surrendered to the rebels. More than 100 fighting men—among them British regulars, needed vitally in Quebec—had been taken prisoner.

One of Carleton’s first actions in assuming command of Quebec was to do what the war council had not dared for fear of causing resentful reaction: By proclamation he ordered every man in the city to enroll in the militia or to quit the town; otherwise they would be prosecuted as spies. By the end of November his garrison of sailors and civilians, supported by his few precious regulars, amounted to 1,800 men.

Tensely the garrison waited for the return of the rebels. Snow fell heavily; ice swirled down the river; rumors abounded. On December 1 a report came in of a party of rebels at Menut’s Tavern, a mile to the west. Carleton, taking no chances, ordered the cannon to open up on the inn. They shot the head off a horse standing outside and smashed the cariole behind. Later it was rumored that Montgomery had just stepped out of it.

The next day a man was reported for making alarmist speeches to the superstitious and highly credulous habitants. They had already been astonished by the light clothing worn by Arnold’s men after their miraculous journey. The provocateur had played on the French word toile (linen) and suggested it should be tolle (ironplate). The belief that the Americans were clad in vests of musketproof sheet iron spread fast, so on Carleton’s orders, one of Quebec’s huge gates was hauled open, and to the noise of rolling drums, the man was made to walk out of the town.

The next day reports filtered through the city that Montgomery had joined Arnold at Pointe aux Trembles with “many cannon” and “4,500 men.”

As usual it turned out to be a wild exaggeration, but on December 5 the sentries on the wall saw in the distance the long American column—the combined forces of Montgomery and Arnold—approaching across the snows of the Plains of Abraham. Not long afterward the bateaux carrying the guns and ammunition were spotted on the river by a naval patrol boat.

The two American forces surrounded the town. Arnold’s men, who had now abandoned their awesome tolle shirts for captured British winter clothing brought up by Montgomery, occupied the suburbs of St. Roch to the north. Montgomery’s troops camped on the plain to the west.

For two days little happened. There was a report that Arnold’s men were building a battery behind a house in St. Roch within a mile of the walls and, according to Thomas Ainslie, a collector of customs serving as a militia captain, “we sent several shots through the house.”

On December 7 Montgomery made an attempt to demand surrender, but since Arnold’s surrender demand under a flag of truce had been rejected, he tried another tactic.

A woman approached the Palace Gate and said she had an important communication for General Carleton. Surprisingly, Carleton agreed to see her, but when she revealed that she had a letter from Montgomery, he ordered a drummer to burn it unread. He held her captive for a few days then had her drummed out of the town with a message to Montgomery that he would receive no communication from a rebel.

Determined to have his letter read, Montgomery had copies fired into the town attached to arrows—with some apparent success, for Carleton sent it home to London. “I am well acquainted with your situation . . .” it warned, taunting that the walls were “incapable of defense, manned with a motley crew of sailors the greatest part our friends, of citizens who wish to see us within the walls. . . . The impossibility of relief . . . point out that absurdity of resistance. . . .”

Carleton did not rate his chances of holding Quebec very highly. “I think our fate extremely doubtful, to say nothing worse,” he had written to London in November. But he himself had besieged Quebec, and he had learned from Montcalm’s error. There was going to be no sallying forth to battle on the plains. He knew that the classic assault tactic—of approaching the walls in trenches—was impractical in the frozen ground; even with his amateur garrison he could ensure that Quebec was a hard place to storm.

At 2 a.m. on December 10 a battery of Arnold’s mortars, set up behind a building in St. Roch, began firing shells—hollow cannonballs, filled with explosives, slow fused to detonate after hitting the ground. Quebec’s 5,000 citizens had long been terrified about the prospect of bombardment by the rebel artillery; in the same way that they respected Arnold’s bulletproof tolle shirts, they had anticipated wholesale disaster. “But,” recorded Ainslie, “after they saw their ‘bombettes,’ as they called them, did no harm, women and children walked the streets laughing at their former fears.”

At daylight the following morning, however, the sentries saw something not so funny: Up on the Cape Diamond heights to the west were the beginnings of an artillery battery, built in thick ice; Montgomery’s men were installing guns ranging up to 12-pounders in size—by no means heavy enough to pierce the walls but more than adequate to cause a lot of damage, overlooking the town as they did.

Four days later the artillery in the new battery opened up. Quebec’s big cannon were trained on the rebel guns; 32-pound and 24-pound solid shot and 13-inch shells splintered the ice protection. “A great pillar of smoke rose . . . on their work,” wrote Ainslie in his journal.

But although the battery was put out of action, it was not against Montgomery’s cannon that the town was mainly tensed. It was against the assault that they knew must come on the night when the rebels stormed the gates.

At four in the morning of the sixteenth, the guards on the walls near the Palace Gate sounded the alarm. Carleton, sleeping in his clothes, was awakened with the news that 600 men were approaching from St. Roch. The drummers pounded out the beat to arms; the cathedral bells pealed urgently. Throughout the town, the garrison hurried to its posts and peered through a heavy snowstorm into the blackness beyond the light cast by the lanterns jutting out from the ramparts. But the attackers never materialized.

Four days later Ainslie wrote in his journal: “Montgomery is reported to have said that he would dine in Quebec or in Hell at Christmas. We are determined that he shall not dine in town and be his own master. . . . The weather is very severe indeed. No man, after having been exposed to the air about 10 minutes, could handle his arms to do execution. One’s senses are benumbed. Whenever they attack us, it will be in mild weather. . . . Ice and snow, now heaped up in places [against the walls] where we have reckoned the weakest, are exceeding strong.”

Two days later it was still bitterly cold. Late that night Joshua Wolfe, a clerk who had been taken prisoner by the rebels, escaped by getting his jailer drunk. Wolfe reported that the rebels planned to storm the town the following night—the twenty-third. Montgomery, he said, was having trouble persuading his men “to undertake a step so desperate.” He had promised them £200 each in plunder. They had 500 scaling ladders made “in a very clumsy manner.”

“Can these men pretend that there is a possibility of approaching our walls laden with ladders, sinking to the middle every step in the snow?” mused Ainslie.

Carleton was not so skeptical. That night 1,000 men were posted on the walls, waiting, staring across the snow, until the sun rose.

It was a wise precaution. For the following day a rebel deserter ran up to the St. Johns Gate on the west of the Upper Town, fired his musket into the air, clubbed it to indicate surrender and asked for admission. Because the guards had orders not to open the gates, they hauled him onto the wall by ropes. He reported that the attack had indeed been planned but Montgomery had postponed it when he realized that Wolfe’s escape would raise the alarm. They would surely attack that night, the deserter warned, unless his own escape deterred them.

But nothing happened, although the guards “saw many lights all around us which we took for signals.” The weather, however, turned milder9—which, so Ainslie conjectured, would make attack more likely. However, as it later appeared, Montgomery planned to attack under cover of bad weather.

On the thirtieth another man deserted from the rebels and reported, wrongly it later turned out, that the Americans were “now three thousand strong having been reinforced from Montreal” and “expressed much impatience to be led to the attack.”10

The next day, New Year’s Eve, it started to snow again in the late afternoon. The wind blew up from the northeast, streaming cold across the icy wastes of upper Canada. By midnight the sentries on the walls were huddling against the battlements for protection against a blizzard.

At 4 a.m. the officer of the guard, Captain Malcolm Fraser of the Emigrants, trudged along the wall on his routine rounds, his body bent before the gale. As he approached the posts at the southern end of the walls, he saw what looked like musket flashes on the heights, but he was puzzled because he could not hear any shots. He questioned the sentries facing Cape Diamond, and they said they had seen the flashes for some time. He moved back along the wall and asked the guards at the next post about the lights. “Like lamps in the street,” was how one man described them.

Fraser guessed that they were lanterns, that the rebels were forming for attack. He ordered the alarm.

Again the drummers pounded out the call to arms. Once again the bells of the city clanged out an insistent warning through the noise of the storm. Officers ran through the streets, bawling to the militia to turn out. Men tumbled from beds on which they were lying in their clothes, grabbed their guns and hurried to their posts.

At parts of the walls, the howling of the wind drowned the alarm. “At some posts,” Captain Patrick Daly recorded later, “neither bells nor drums were heard.” But the guards were soon aware that the assault they had been expecting so long had come at last.

Two rockets whooshed skyward in quick succession from Cape Diamond by the St. Lawrence. Then the firing started. Rebels shooting from the cover of rocks on high ground by Cape Diamond were only 80 yards from the post on the ramparts and at a level that was almost as high.

But by firing, the rebels exposed their positions. “The flashes from their muskets made their heads visible,” recorded Ainslie, “we briskly returned the fire.”

Farther north, on the wall by the St. Johns Gate, the gunners had fired flaming shot to illuminate the approaches beyond the circles of light thrown by the lanterns thrust out from the ramparts on long poles. Anxiously they stared through the snowstorm toward the suburbs of St. Johns that were a good starting point for an assault.

The attack came fast—men running from the far blackness of the houses toward the gate, the flickering fireballs turning them into dark giant moving shadows.

The big guns crashed out, the muzzles flaring white flame, jerking back on their carriages until they strained the retaining ropes. Hundreds of leaden grapeshot flayed into the ranks of the advancing men. Between the guns, the militiamen lined the walls, shooting volley after volley of musket balls at their attackers.

Again and again the cannon fired—the explosions blocking the stinging ears of their unaccustomed crews.

Still the rebels came on until they were almost at the big gates. Then suddenly they broke and ran. It was, so the British discovered later, only a diversion with no intention to follow through, but, to the men on the walls, it had looked determined enough.

Meanwhile, the men posted above the Palace Gate, on the north of the city, facing the St. Roch suburb, were suddenly alerted. There the walls merged into tall buildings, the backs of which overlooked the St. Charles River far below. At the foot of the buildings, above the wave-washed rocks, was a path that led down around the eastern edge of the town to the port.

Shells from the rebel mortars in St. Roch had been falling for some time. Now suddenly the guards over the gate—their attention diverted until then by the noise of attack on the west—noticed in the dim light a long column of men in single file passing silently from the direction of St. Roch down the rock path to the harbor The column, already going by below them, was too close for cannon. The militiamen opened up with their muskets.

Seamen from the ships in the port were manning the eastern windows of the Hôtel Dieu. As the rebel file passed below them so Ainslie reported, “they were exposed to a dreadful fire of small arms which the sailors poured down on them.” As one of the Americans, John Henry, recorded later: “They were even sightless to us. We could see nothing but the blaze from the muzzles of their muskets.”

The pathway was rough, heaped with rugged piles of ice and soft snow. Fireballs, lobbed from the town, illuminated the long line of slipping, sliding men, some of them carrying scaling ladders, as they worked their way down toward the harbor. To the defenders above they made easy targets; gaps were ripped in the file by the musket shot; men jerked and toppled into the snow.

But despite the heavy shooting from above them, the rebel column still went on, stepping over dead and wounded comrades toward the Lower Town.

The Lower Town, the underbelly of the fortress city, was, as Carleton had fully realized, where Quebec’s true weakness lay. Lo£ palisades and barriers supported by guns and men with muskets blocked the streets that led from the wharves and from paths such as the one to the east that Arnold’s men were now descending under heavy fire.

There was another route that stretched out of the Lower Town—this one to the west, along the rock face of the towering Cape Diamond to Wolfe’s Cove. Narrow, cluttered with snow and ice, bordered on one side by bare cliff, it dropped sheerly to the St. Lawrence below.

The main defense of this entrance to the Lower Town was a blockhouse formed out of an old brewery building that commanded the upward curving roadway from behind a log barrier. There a small battery of 3-pounder guns had been set up with their barrels jutting out of the windows. To man and support it with small arms were some fifty men, most of them Quebec residents, but they were backed up by eight seamen from the ships in the port and a Royal Artillery sergeant, the only professional among them. In command of the post was Captain Barnsfare, master of a merchantman, and John Coffin, a Boston Loyalist who had refused a militia commission but, in view of the crisis situation, took on “the authority of an officer.”

From the windows of the blockhouse, Barnsfare and his men stared out toward the bend in the road—only faintly visible in the dawn light and falling snow. The gunners had lighted matches waiting ready.

Then they saw them, at first just a suspicion, a sense that there was movement out there in the gray storm, followed by the certainty: a group of shadowy figures with the snow swirling around them. They appeared to be an advance unit, for they stopped as soon as they saw the blockhouse as though waiting for the main body to catch up.

Tensely the men in the blockhouse watched the attackers. “We shall not fire,” Barnsfare warned, “until we can be sure of doing execution.” Coffin had taken charge of a party of British Canadians who stood at the open windows with muskets at the ready.

At last, the rebels began to advance slowly. The gunners in the blockhouse waited for Barnsfare’s order. As they walked, the Americans scuffed the snow with their feet, looking almost unreal in the half-light. When they were about 50 yards away, they stopped again “as though in consultation.” Then one of them moved forward alone, peered at the barricade and the blockhouse for a moment and returned to the others.

Again, for a few minutes they seemed to be discussing what to do. Suddenly, as a group they made a dash—all of them running fast to storm the barricade. Barnsfare still waited, watching the rebels advancing swiftly. Then at last, as the nearest men were almost at the barricade, he gave the harsh order: “Fire!”

The explosions as the guns went off in those close confines were deafening. The musketmen squeezed their triggers and swiftly reloaded. “Our musketry and guns,” Ainsley wrote, “continued to sweep the avenue leading to the battery for some minutes. When the smoke cleared there was not a soul to be seen.”

Not on their feet—but thirteen bodies11 lay in the snow, and two of them were groaning.

The slaughter of the close-range firing seemed to have convinced the rebels that the post was held too strongly, for they did not attack again.

Carleton was directing the defense of the city from the Upper Town in the Place d’Armes, where the mobile reserve was held waiting. He knew now that the attacks on the walls at Cape Diamond and St. Johns had been feints, designed to divert the defenders’ attention from the real target—the Lower Town, now under assault from both east and west. He had already ordered an artillery officer to hurry down with a militia company to support Barnsfare, who had been reported under heavy attack.

Now he received news of the assault from the east side of the Lower Town that was far more serious. Some schoolboys, according to one report,12 hurried into the Place d’Armes, shouting, ‘The enemy’s in possession of the Sault-aux-Matelot.”

The Sault-aux-Matelot was a very narrow street that led from the waterside into the Lower Town. It was the route for any attack around the outside of the city from the direction of the St. Charles. For this reason, it was strongly defended at the point where the rebels would enter—a high log barricade, well manned and armed with two cannon.

Since it should have been able to withstand a sustained attack, at least until a message could have been got to Carleton asking for support, the information that the enemy had broken through so quickly was very surprising—a breakthrough that was due, it was later charged, to the fact that the officer in command of the ports was a rebel spy.

But the critical aspect was that the Sault-aux-Matelot led directly into the main part of the Lower Town, and once the rebels gained control of that, they would have a very strong base from which to assault the Upper Town.

At first Carleton did not believe it. He sent Maclean down to check. Carleton was an experienced fighter. When the colonel returned with confirmation, he swiftly planned his strategy. The Sault-aux-Matelot had cannon-supported barricades at each end; although the rebels had broken through the first, they had, according to Maclean’s report, paused in the street before the second barricade.

Why they had not yet attacked this was not clear, but it was obvious that the assault would soon come. And it was vital to Carleton’s defense planning that when it did, they should be held at this point.

Now Carleton sent the militia Colonel Henry Caldwell down to reinforce the defense at the vital barricade at the end of the Sault-aux-Matelot. With him the colonel took Carleton’s handful of fusiliers—virtually the only regulars in Quebec—and a substantial force of militia and sailors.

At the same time the general ordered another strong detachment to march out of the Palace Gate in the north wall of the city and down the same rock path above the St. Charles which the rebels had traversed earlier under fire to attack from the rear.

The plan to trap the rebels in the narrow Sault-aux-Matelot was brilliant, but it depended completely on Caldwell’s holding the barricade.

He arrived only just in time. The rebels were just about to assault the high log stockade that blocked the Sault-aux-Matelot. Scaling ladders were already propped against the barrier.

Caldwell had more room in which to deploy his forces than the rebels had in the narrow street only 20 feet wide. The road curved upward away from the Sault-aux-Matelot, then split into two branches. Swiftly he ordered the fusiliers into line, backs against the houses, facing the barricade with fixed bayonets. From there they could fire at the rebels as they mounted the tops of their ladders and charge with the bayonet if any of them succeeded in getting over the stockade.

Some of the militiamen, on Caldwell’s instructions, hurried into the nearby houses so that they could fire from the upper windows both at the barricade and over it into the men crowded in the narrow street behind.

As part of the planned defense of the post there was a cannon mounted on a platform, positioned so that it could fire over the stockade.

The rebels charged, clambering up the ladders onto the barricade, and the fire from the defenders mowed them down. Again and again they attacked as musket shot and grape from the barking cannon raked the top of the log barrier.

It soon became obvious that no one could get over the 20-foot summit of the barricade alive against Caldwell’s murderous density of shot. The rebels’ only course was to weaken the defense, holding it down with heavy fire, while they stormed again. So they swarmed into the houses on either side of the Sault-aux-Matelot and opened fire from the upper windows, concentrating their shooting from the cover of the stone walls on the cannon crew who were well exposed on their platform.

As an assault tactic it succeeded. The gunners leaped from the platform to take cover. On Caldwell’s orders another gun was set up farther back along the curving hill road. This was out of sight of the rebel marksmen, but because of its high position, it could fire on the houses that were sheltering them. Solid shot began to drop through the roofs, smashing the floors and stone walls.

Because of the narrow area on which Caldwell could concentrate his musket fire, none of the Americans had yet got over the barricade, but at one point they came close. They swung a laddei over onto the defenders’ side of the stockade, but a burly French Canadian named Charland rushed to the barricade, exposing himself to point-blank fire through the loopholes and wrenched the ladder away.

Almost immediately the colonel was faced with new danger. The rebels had entered a house on one side of the barricade whose doorway was in the Sault-aux-Matelot, but some of whose side windows overlooked Caldwell’s main defense position. From there they would be able to shoot down at close range on the fusiliers and militia in the street below them.

It was a critical moment. A Highland officer grabbed the captured ladder, placed it against the side of the house, then leaped up it, followed by the others. They met the rebels coming into the room and fought them back down the stairs.

“I called out to Nairne in their hearing,” Caldwell reported later “that he should let me know when he heard firing on the othei side”—from the lay party, in other words, that Carleton had sent outside the city to attack the rebels from the rear.

The general’s design to trap the Americans in the Sault-aux-Matelot worked exactly as he planned. His men swarmed over the barricade at the other end of the street and demanded surrender from the rebels, now hemmed in from both sides.

The first prisoners, each with a label pinned to his hat worded “Liberty or Death,” were passed through the window and down the ladder from the house that Nairne had taken. Then Caldwell had the gate in the barricade opened for the remainder.

Arnold had been wounded and carried from the town, leaving in command Daniel Morgan—a man who, together with his unit of expert Virginian riflemen, was to become one of the rebel field officers most respected by the British army. Morgan, who had once been flogged for striking an officer in the French and Indian War, hated the British; now defiantly, with his back against a wall, he refused to hand over his sword to his captors. They threatened to shoot him, and his own men begged him not to risk his life. He saw a priest among the watching crowd. “Are you a priest?” he snapped.13 The priest said he was. “Then I give my sword to you,” he conceded, angrily. “But not a scoundrel of these cowards shall take it out of my hands.”

In all, 426 rebels were taken prisoner. Carleton took advantage of the demoralized American forces and sent out a raiding party to capture Arnold’s mortars in St. Roch.

Among the bodies lying in the snow outside the blockhouse on the western side of the Lower Town was the corpse of the rebel General Montgomery. Carleton, who was often magnanimous, ordered a burial with full military honors.

Carleton had held Quebec. He had badly mauled the rebel force. He had left Arnold, now commanding from a hospital bed in St. Roch, with barely 600 men, but the British were still under siege. There could be no relief until the spring. Arnold, on the other hand, could be reinforced and could then storm the city again. Although the morale of Quebec’s defenders had received a big boost, their prospects of holding out were in truth no better than they had been before.

By that blizzard-bound New Year’s morning of 1776 the colonial revolt had left Britain with only two slender toeholds14 in the enormous territory that it had once controlled through its network of governors: Quebec, under total siege; and Boston, hemmed in from the land side by a vastly superior force in numbers, now commanded by George Washington.

And compared with Quebec, which, even though facing the threat of another attack, had adequate supplies for months, conditions in the Massachusetts port were serious.