9

NEW YORK HARBOR, July 12, 1776

It was nearly seven o’clock on one of those pristine pink-skied evenings that were a feature of the New York summer when the big 64-gun flagship Eagle, with its sails full and the slim white admiral’s pennant snaking from the top foremast, progressed slowly down the line of anchored ships, each firing its guns in salute as she approached and passed.1

For two weeks 138 British vessels had lain in the harbor, swinging on their cables near the flat shore of Staten Island, where Howe’s army, evacuated from Boston via Halifax, was camped in long, neat rows of round white tents. Now on this brilliant July day, the general’s elder brother was joining him with yet another army in a huge armada of 150 ships that were streaming through the Narrows between Staten and Long islands that formed the entrance to New York. And even this was not all: Two more fleets were on the way.

From the Eagle’s quarterdeck—as the warship moved steadily through the fleet, cheered on, according to an eyewitness, by the sailors in the ships and the soldiers on the beach—the admiral could see the immediate objective of the biggest military force that Britain had ever sent overseas: the town of New York, a dense cluster of houses and churches cramped on the tip of the hilly, wooded Manhattan Island, the new headquarters of George Washington and the rebel army.

He could survey, too, the magnificent Hudson2 River. Streaming along the west bank of Manhattan, it reached up straight and wide through eastern America toward Lake Champlain and Canada, where Carleton’s teams of sweating sailors were dragging his ships in sections around the rapids of St. Johns. Soon, it was planned, Carleton would strike south with his force of 10,000 soldiers as the Howe brothers swept north to meet him with their big army that would then total nearly 35,000 men.

The cable rattled noisily as the Eagle’s anchor splashed into the water and checked the way of the big ship. From the Staten Island beach, a longboat carrying William Howe pushed off and headed for the warship. The general had much to report to his brother.

Only the previous day, a Declaration of Independence, issued by the Congress in Philadelphia on July 4, had been announced in New York. From the ships and the camp on Staten Island, the British had seen the bonfires and heard the celebratory booming of the rebel cannon.

Now, so far as the delegates to Congress were concerned, the thirteen provinces were no longer colonies in protest against the treatment of the mother country; they were self-governing states. The rebellion had been transformed into a war. In their eyes, any claim that King George III may have once had to American territory was gone. His role, or at least the nearest role to a royal sovereign possible in a loose federation of states that had just been established, had been assumed by the flamboyant John Hancock, the president of the Congress—advised, of course, by the Machiavellian Samuel Adams.

To the British the Declaration of Independence was one more act of treason by rebels. “It proclaims the villainy and madness of these deluded people,” sniffed Ambrose Serle, the admiral’s secretary, as he wrote his journal on board the Eagle that night. But the Howes were Whigs, and even though they were heading up a massive military machine, they were sympathetic to the American grievances.

They had come to New York not only to stamp out a revolt but as peacemakers, with the King’s commission to restore the Anglo-American relationship to what it once had been. Their powers were limited, and it is highly doubtful if their peace mission could ever have been successful; but the new action by Congress had produced an enormous obstacle. After that, how could anything be quite the same again? By definition the Howes’ brief was now impossible.

Also, the Declaration of Independence altered drastically the position of those Americans who were still loyal to the King. For if the Congressional edict had any relevance at all, it meant that the Tories were no longer merely men who did not happen to agree with the patriots; they were traitors. If they cooperated with the British, they would be aiding the enemies of their country. The period of the tar and feathers was over; their punishment would be death. As William Howe had now seen clearly, there were a large number of Loyalists—or traitors, as Washington and his army would now regard them—in the province of New York. And never had they been so ardent in their enthusiasm to support the King of England.

Before the Declaration of Independence, the rebels had stopped short of actually executing Loyalists. But the news of Britain’s preparation for the big summer push, with the inevitable invasion of New York, had sparked an active campaign against them. In a series of punitive edicts, Congress had declared it a crime, punishable by jail and fines, to help the British in any way or even to dissuade people from uniting against Parliament.

The wave of arrests that resulted was so large that special committees had to be set up to administer what was inevitably very rough justice. “Tory baiting” by the New York mobs became far more prevalent as the rebel authorities, though deprecating it officially, carefully averted their eyes and even on occasions encouraged summary action. Angry crowds pillaged Tory homes and plunged into an orgy of rail riding.

And the Loyalists, only too aware of the armies on their way across the Atlantic, waited eagerly for the chance of revenge that now seemed imminent.

When General Howe put his troops ashore on Staten Island, there was no sign of an enemy; Washington had decided not to contest the landing but to hold his army for a conflict nearer Manhattan.

The beach was crowded with hundreds of welcoming Americans. By contrast with the months of blockade in Boston, there were many willing suppliers of food, horses and the army’s other needs. “The fresh meat our men have got here,” Lord Rawdon was soon to write home, “has made them as riotous as satyrs. A girl cannot step into the bushes to pluck a rose without running the most imminent risk of being ravished, and they are so little accustomed to these vigorous methods that they don’t bear them with the proper resignation, and of consequence we have most entertaining courts martial every day. . . .”

One girl, reported Rawdon, complained to Lord Percy that she had been deflowered by some grenadiers. The earl asked her how she knew they were grenadiers, since it was dark at the time. “Oh, good God,” she answered, referring presumably to their size, “they could be nothing else and, if your Lordship will examine, I am sure you will find it so.”

Despite the dangers to their women, so many Loyalists streamed into the British camp eager to enlist that Howe established a special American unit. Almost as important, they provided him with a large source of expert guides with detailed knowledge of the rugged country through which his army would have to fight. And by contrast with the farmhouse snipers who had savaged the British so badly on the Concord road, this time there would be sympathizers in many of the homesteads as the army advanced.

Howe had toyed with the idea of an immediate attack on Long Island, but its timbered hills, broken by narrow passes easy to defend and already fortified by Washington, had deterred him. He set up his base on Staten Island, planning to wait for the reinforcements that were on their way and, in particular, for camp equipment and wheeled transport which his army badly needed. As always with Howe, there was plenty of time—and, of course, Mrs. Loring3 and the faro table, where, according to one report, she lost 300 guineas in one evening’s play.

In fact, he made his first remotely militant move only a few hours before his brother sailed through the Narrows. At noon two frigates, the Phoenix and the Rose, made a run up the Hudson under heavy fire from rebel batteries to the Tappan Bay (Zee) on the north of Manhattan. There they were able to control the river supply route to the rebel army and to arm local Loyalists.

Two days later Lord Howe made his first move to negotiate in his role as a peacemaker with Washington. He sent a lieutenant over to the town in a longboat under a flag of truce, but the rebel commander refused to receive the letter the officer carried because it was addressed to George Washington Esq. with no reference to his status as general. Two days later, delivery was rejected even of an answer to a letter of his own because it was not properly addressed.

Ambrose Serle, the admiral’s secretary, was incensed. “We strove as far as decency and honour could permit . . . to avert all bloodshed . . . ,” he scribbled angrily in his journal. “And yet it seems to be beneath a little paltry colonel of militia at the head of a banditti of rebels to treat with a representative of his lawful sovereign because it is impossible to give all the titles which the poor creature requires.”

The Howes knew that Washington was not being petty-minded any more than they were. “Esq.” was the normal way of addressing untitled senior officers in correspondence, but by making an issue of his rank, Washington was trying to force the British commanders to acknowledge the existence of the Congress which had granted it to him. Indeed when William Howe eventually did address him as general, Washington promptly asserted that this constituted recognition of the illegal rebel government and, as a logical consequence, of American independence.

Also, the issue was significant from a military viewpoint. Legally a rebel captured in the field could be hanged. The prisoner of an acknowledged enemy army could not. Although the British do not seem to have executed any captured men, their attitudes to the Americans were certainly colored by their revolutionary status. They were, after all, only “damned rebels.”

In any event, Howe achieved nothing by his concession. When Washington received the British Lieutenant Colonel Patterson, he asserted that he was not empowered to negotiate peace terms, and so far as he understood, Lord Howe himself could do no more than grant pardons, which the Americans did not seek.

The elegant general offered the colonel a drink, which he refused politely, and introduced him to his staff officers. “Has Your Excellency no particular commands,” asked Patterson before leaving, “with which you would please to honor me to Lord and General Howe?”

“Nothing,” answered Washington airily, “but my particular compliments to both.”

For four weeks the British waited. Meetings took place constantly on board the Eagle with a stream of visitors—refugee governors, Tories, military and naval officers—as slowly the plans for attack developed. Boatbuilding for the assault across the water was in progress, mostly of the round fronted flatboats for the troops, but the program included some big shallow-draft barges with a novel construction:4 They had flat bows that could be let down to form a ramp so that guns could be hauled aboard.

Meanwhile, according to Serle, a report arrived on the Eagle that Carleton’s army from the north would soon be at Albany on the upper reaches of the Hudson. Fortunately it made no difference to the Howes’ plans, for the truth was that Carleton was still shipbuilding at St. Johns.

On August 1, Serle recorded, “between forty and fifty sail appeared in sight.” It was the ill-fated Southern expedition that had been planned to encourage the Loyalists.

A Tory force scheduled to rendezvous with the newly arrived British troops had been attacked and defeated on its way to the meeting point. Despite this, the British attempted to establish a bridgehead at Charleston, South Carolina, to serve as a rallying area. As a first stage of a hurriedly replanned operation, they attacked Sullivan’s Island, whose batteries dominated the narrow approaches to the port. It was an utter disaster. Ships ran aground; there was conflict between the naval and military commanders and confusion among the assaulting troops. The rebels fought off the attack. The British lost 170 men and a frigate; several other vessels were severely damaged.

Clinton had been sent down from Boston before the evacuation to rendezvous with the fleet and take military command. He had never been keen on the operation, and its failure, which he blamed bitterly on the navy, made a deep impression on him. The unhappy memory would still be with him when he returned to attack the port three years later with a degree of caution that was highly pedestrian but extremely successful.

Clinton had brought Howe 2,000 more troops. Twelve days later another big fleet sailed through the Narrows and moved into the anchorage to the welcome of the shouting sailors and the booming of the saluting guns. The Hessians—mustachioed, precision-drilled, rented fighters in gaudy uniforms—had arrived.

The army considerably outnumbered the American force and was far superior in equipment and fighting experience. Staten Island was a mass of tents, artillery parks and supply depots. There were now nearly 400 British ships anchored in the harbor.

New York was highly vulnerable to attack from the water. The East River, which flowed down the east side of Manhattan Island into the Hudson at its southern tip, was navigable to the biggest ships. Though the rebels had set up gun batteries to challenge entry into the river, if these could be silenced, the town could be bombarded from all sides.

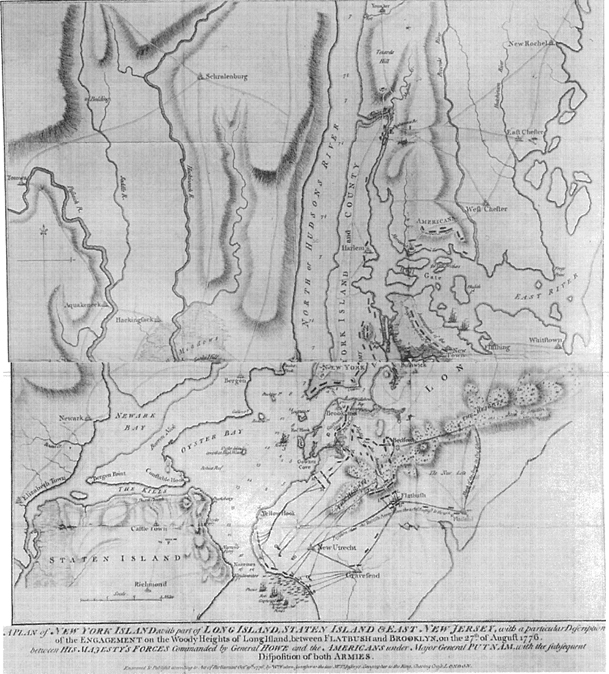

Howe planned to leapfrog his army onto Manhattan by landing first on Long Island. Then, supported by ships and batteries on the north shore of Long Island, the British would attack across the East River and take New York. The main military obstacle would be the ridge of hills, the Heights of Guana, that rose abruptly from the plainland and reached east from the Narrows for some 10 miles. The hills were not high, but they were thickly wooded, and dominating the surrounding country as they did, they provided a strong defense barrier.

The arrival of the Hessians removed Howe’s last excuse for delay. A week later he completed the final preparations for the attack, and in the leisurely timetable he favored, the buildup began. On the evening of August 19 the German troops, whose camp was in a different part of Staten Island from the British, loaded their equipment into little red pony carts and marched to the beach that faced Long Island across the Narrows. There they pitched their tents in two lines, ready for embarkation at short notice.

The next morning the commanders held their briefing conferences—the naval captains assembling on board the Eagle and the senior military officers attending General Howe’s headquarters in a house on shore. There was little element of surprise. From New York and Long Island, even though they did not know the exact landing point, the rebels could see exactly what was happening. For the whole of the following day the biggest British army that had ever invaded enemy-held territory prepared for embarkation. Horse teams hauled the forty field guns—which were to cross the Narrows with the troops—into parks near the water where they could be loaded into boats constructed for the operation. Wagons for ammunition and baggage were lined up ready.

That evening 5,000 troops, mainly Hessians, were put aboard troopships. These would anchor near the landing beaches as a springboard for the support infantry, cutting down the distance the assault boats—which would take the first wave across the Narrows from Staten Island—would have to go to collect troops for the second wave. The remainder of the 15,000 men who were to take part in the first stage of the invasion were camped near the embarkation beaches, waiting only for the final order.

On the evening of August 21 General Howe, to be close to the all-important amphibious control, went aboard the Eagle and ordered his staff to join him there early the following morning.

Then the storm came up. Again and again, great peals of thunder shook the New York islands. Lightning forked across the sky, brilliantly exposing their target town to the two brother commanders who were waiting on the heaving, creaking flagship. Tugging at their cables, the transports and the frigates wallowed in the big sea built up by the howling northeast wind. On the Staten Island shore, the screaming gale lashed solid sheets of rain into the thousands of tents.

It was one of the worst storms in the history of New York—“more terrible,” according to the contemporary Pastor Shewkirk, than the one that had “struck into Trinity Church” twenty years before.

On Long Island’s wooded hills, the waiting rebel troops suffered even worse than Howe’s army. Four of them, it was learned later, were killed by lightning.

The storm died almost as abruptly as it had blown up. Soon after midnight the wind had veered to the west and subsided to a mild breeze; the water in the Narrows was calming.

Aboard the Eagle, between one and two in the morning, Lord Howe’s flag captain, Henry Duncan, according to his journal, awoke the admiral and told him he was ordering the transports under way. By the time the troopships had weighed anchor on Duncan’s signal the Phoenix and the Rose, which four days before had run the gauntlet of the rebel batteries on a fast return dash down the Hudson, had moved quietly down the harbor to take up station off the landing beach in Gravesend Bay on Long Island. With them to cover the assault were three other ships. One of them, the Rainbow, dropped anchor off Denice’s Point on the west of the main attack shore, where the ferry which plied across the Narrows always docked. By the ferry stage was a large stone building that Tory informers had warned was a fortified blockhouse.

By four o’clock the transports had anchored near the warships at Gravesend, and the assault flotilla was waiting at the Staten Island embarkation beach: seventy-five red and white flatboats for the infantry, and bigger craft, eleven barges and two galleys, to transport the horses and the cannon and the wagons.5 All the craft were designed purely for transport—rafts, in effect, fitted with gunwales. They were broad and unwieldy boats whose shallow draft, necessary for beaching, left little bulk below water level to hold them steady against a crosswind.

In the dawn light apparent chaos marked the long sandy embarkation beach—thousands of scarlet-coated men marching in different directions as they moved to the takeoff areas intermingled with cannon and wagons being hauled through the soft sand by the horse teams to the water’s edge.

The assault units—the first wave would carry 4,000 men—were formed up in ranks on the shore. As usual, Britain’s crack troops—the light infantry with their familiar tricorn hats and the tall grenadiers in black bearskin caps—were to storm the rebel beach and establish the bridgehead for the landing of the cannon, the cavalry and the followup infantry.

By companies the assault troops marched down to the water’s edge to board the flatboats, held steady by the sailors. Each craft was big enough to accommodate fifty men. Farther along the beach plank ramps had been fitted to the bigger craft. As the sky lightened, cannon were being manhandled up the ramps with the help, in the case of the bigger guns, of the tall tripod pulleys always carried by the artillery. In other boats, horses were being led and lashed up the planking into the craft for the crossing.

By eight o’clock the sun was up behind Long Island and the assault troops were embarked. By then the Howe brothers had crossed to Gravesend Bay by boat and had gone aboard the Phoenix, which was to be the headquarters ship for the operation. On Lord Howe’s orders a signal cannon on the Phoenix barked; a blue-and-white-striped flag was hauled up to the mizzen top mast.

The coxswains in the crowded boats off Staten Island rasped their commands. Hundreds of oarsmen dropped their blades into the water and heaved. The boats formed in ten lines, bows to stern, and headed across the Narrows. The soldiers—their muskets, with bayonets fixed, held butt down on the deck between their knees—sat cramped together in the heart of the boats as the sailors, sitting near the gunwales, hauled on their oars.

Slowly, the flotilla passed the transports and on through the lines of warships, lying at anchor with springs on their cables, gunports open, gun crews waiting with lighted matches.6

The country behind the long white sandy landing beaches was flat plainland with little cover for defending troops-pastureland mainly, with a few farmhouses farther inland. All the indications suggested that Washington was not planning to contest the landing; from the Phoenix the commanders could see a few scattered rebel units, but they were moving inland. Smoke spiraled from several points where they had fired cattle fodder to keep it from falling into British hands. Threatened by the Rainbow’s guns, the rebels in the blockhouse at Denice’s Point had evacuated the building.

As the flotilla neared Long Island, Commodore William Hotham in a leading boat displayed a red flag; the craft deployed in line abreast, moving steadily toward the shore. There was no sign of opposition and no apparent need for storming tactics. “In ten minutes, or thereabouts,” recorded Captain Duncan, “four thousand men were on the beach, formed and moved forward.”

The flatboats pushed off from the beach and headed for the transports anchored offshore to collect the Hessian grenadiers and the sharpshooting jaegers. Unlike the British, the German troops did not travel the short distance across the water sitting down; they remained standing rigidly to attention in the boats with their arms sloped.7 Their martinet officers were never happy unless their men were formed in tight ranks.

Certainly, the visual effect was striking—the grenadiers, in their blue uniforms with turned-back tails and the tall metal-faced high caps resembling bishop’s miters, and the tricorned jaegers in green uniforms with scarlet cuffs. Like the rebel backwoodsmen, the jaegers, who were recruited from the German forests, were armed with rifles, as opposed to the smoothbore muskets, and they handled them with expert accuracy.

By midday the heavy bateaux and galleys had brought over the cannon and the wagons. The horses of the dragoons had been landed at the ferry quay at Denice’s Point, and 15,000 soldiers disembarked. General Howe had landed and set up temporary headquarters in a house in New Utrecht, a mile from the coast. The troops were pitching their tents, forming a vast encampment stretching some four miles along the coast from the Narrows to the town of Flatlands.

That afternoon a brigade of the light infantry and Hessians probed forward. In command was thirty-nine-year-old Charles, Earl Cornwallis who had crossed the Atlantic with the force that attacked Charleston. Like Clinton, he had fought in the school of officers who considered themselves an elite because they had served in Germany, as opposed to America, in the Seven Years’ War. He was a heavy, awkward man with a cast in one eye, and although he was now comparatively junior in the hierarchy of senior officers, he was to play a critical central role in the British operations in America.

Cornwallis’ brigade advanced toward the hills under orders to capture the little village of Flatbush, which lay immediately below one of the three passes through the Heights of Guana. As they marched along the road to Gravesend, the first village in the route, they could see the rebels ahead of them across the plain slaughtering the cattle they had not yet been able to drive off and firing the hayricks.

At Gravesend Cornwallis checked his main force and sent on the advance guard of Hessians with six cannon to take Flatbush. The rebels were in possession of the village. Colonel Carl von Donop, the German commander, called up his guns, and the Americans fell back toward the Flatbush Pass in the hills, where they had built a strong redoubt. The Hessians entrenched just outside the village.

Howe had given Cornwallis specific orders not to press on through the pass if it was defended; having tested the strength of the rebels at that access through the hills, he was required merely to hold Flatbush Village. For the next few days, while the main British force remained immobile in its vast camp along the coast, the rebels raided the Hessian lines several times; but the assaults were minor, and the Germans held their position until they were finally ordered to drop back.

Meanwhile, in his usual unhurried way, Howe was considering his plans for the attack through the hills. And Clinton, in his usual anxious way, was worrying about Howe’s relaxed approach to generalship. Just as he had done on the night before Bunker Hill, he carried out a little private reconnaissance.

Clinton was second-in-command of the British army, yet incredibly he had no informal access to his general. He appears to have seen Howe only when he was summoned, and even then there seems to have been little discussion. Clinton conveyed most of his thoughts on strategy in a series of rather petulant memorandums, which Howe obviously found so irritating that he rarely commented on them. Most of Clinton’s contact was with the staff officers at HQ.

It is not hard to sympathize with Howe. His second-in-command had many qualities as a general—he was industrious, brave and intelligent—but he seems to have been utterly humorless and to have nursed a constantly burning sense of grievance. Like Lord George Germain, he was a solitary man. A picture emerges of him carrying out his lone reconnaissances, only just veiling his poor view of his chief in his memorandums, working late into the night in his tent on independent schemes that induced weary sighs of bored exasperation from the planning staffs at HQ. There is a Clinton in every military community—clever but so pernickety and dogmatic and lacking in charm that the impact of the talent is greatly blunted. This time, however, Clinton’s suggestions were noted, albeit reluctantly, and finally acted on.

Howe had a whole range of alternatives open to him. The rebel army had fortified Brookland, on the northern tip of Long Island just across the East River from New York, with a line of forts, linked by thick walls. But before any attack could be launched on the big rebel redoubt, Howe had to get his army through the hills—either, so it seemed at first, by the Gowanus coast road which reached around the western edge of the hills alongside the Narrows or by the two passes which broke through the hills from Flatbush. Like the Gowanus road, both led to Brookland, but one detoured west through the hill village of Bedford.

Whether Howe took one route or attacked on all three at once, the conflict was clearly going to be bloody. For the rebels would be entrenched high above the roads under the cover of trees and boulders—just the kind of country suited to the Indian fighting tactics at which they excelled, as they had demonstrated so vividly on the Concord road.

Clinton worried away at the problem even though nobody had invited him to do so. He reconnoitered the three passes—presumably from a distance by horse, for he decided to go far farther west than Howe appears to have considered and discovered “a gorge about six miles from us” from which the rebel position “may be turned.”

The main highway that led from the ferry at Brookland to the town of Jamaica and from there on along the middle of Long Island passed the Heights of Guana through Bedford. For some miles it lay just to the north of the hills, then broke through a small pass and reached for the rest of the way under the south side of the heights. This pass was the “gorge” that Clinton had found. Eagerly pointing out that the terrain suited the use of cavalry in the advance units, he urged a secret push in force through the pass. If the movement were successful, it would mean that the British could attack the rebels from the rear while the other units assaulted from the front. At the same time—“as the tide will then suit”—a squadron of warships could blaze their way up the East River and bombard the rebel lines at Brookland.

To concentrate the enemy’s attention away from the Jamaica gorge, Clinton urged, the British should mount initial attacks at the other passes that “were not too obstinately persisted in” until the big flanking column was through the hills and behind the rebel positions.

It was, without question, a beautiful plan. Howe’s chief staff officer, Sir William Erskine, agreed to “carry it to headquarters, where, however,” as Clinton recorded sardonically, “it did not seem to be much relished.”

Howe’s reaction can be seen clearly in Clinton’s writings. This irritating, dry and overzealous officer, who was always bothering him with pompous self-opinionated suggestions, had come up with an idea that was truly sound. For two or three days Clinton heard nothing. Then Howe sent for him. The commander in chief was not enthusiastic. “In all the opinions he ever gave to me, [Howe] did not expect any good from the move.” But stony-faced, he agreed to the plan. Clinton would be in charge of the avant-garde, the traditional role for the second-in-command; he was to seize the pass and wait for Howe, who would follow with the main part of the army.

Meanwhile, 5,000 British under Major General James Grant would be attacking along the Gowanus road near the Narrows. The Hessians, now reinforced by another 5,000 men under General Philip von Heister, would make an assault from Flatbush.

Neither of these movements would be pressed through until the flanking column fired a signal cannon to indicate that they were behind the rebels at Bedford and ready to launch their attack.

The afternoon of August 26 was hot. The sun, still high over the Atlantic, glared on the dry plain. Heat simmered from the dusty ground, distorting the vision, oppressing Howe’s soldiers in their heavy all-season uniforms.

Outside Flatbush, the Hessians were fighting off the biggest attack the rebels had yet directed at their lines. Because the conflict had no significance in the new operation, Cornwallis ordered them to drop back on the village. Later that day he withdrew the British units that were with them.

General Sullivan, in command of the rebel units at the Flatbush and Bedford passes,8 must have watched the long scarlet column snaking slowly across the plain toward the village of Flatlands near the coast and pondered on the British purpose. Howe intended that he should be kept in doubt. Camp was usually struck immediately before an operation. But on the commander’s orders, the British tents were still there, pegged out in their long lines, stretching along the coast.

Soon after seven o’clock that evening the flanking force paraded on the village green at Flatlands. For all of Howe’s lack of enthusiasm, it was big. Ten thousand British troops would attempt to march undetected along the coast road toward Jamaica before breaking across country to drive through the pass.

Even Clinton’s avant-garde, paraded that evening by the village, was substantial: nearly 1,000 mounted dragoons, more than 2,000 foot soldiers, most of them grenadiers and light infantry, and fourteen cannon.

The dragoons, with feathered black helmets, scarlet coats and thigh boots, were light mobile cavalry, trained for the new type of flexible warfare that was developing. They were armed with long swords, pistols and fusils which they were taught to fire from the horse, sometimes at the gallop, taking care, as one military manual urged, to avoid shooting directly ahead, if possible, because this would put the barrel unpleasantly close to the horse’s ears.

But unlike the heavy cavalry, the dragoons would often fight on foot if the situation demanded it, using their horses merely as a way of moving fast from one position to another. They were invaluable in the type of war Howe was now fighting.

At eight o’clock, so Clinton recalled, he gave the order for the avant-garde to march. A small advance unit, under Lieutenant William Evelyn, went on ahead. Clinton followed at the head of the cavalry. Then came 1,000 light infantry. Behind them was Lord Cornwallis, riding at the head of his brigade made up of grenadiers and a couple of ordinary line regiments. Last of all were the cannon, with the blue-coated artillerymen riding on the carriages and civilian drivers walking beside the horses. Howe and Lord Percy were to follow later that night with the main part of the force.

It was the noise of the cannon wheels “over the stones” that caused Clinton his main anxiety. Already, before the column had started off, he had sent out a regiment of Highlanders to scour the country within earshot of the road and gather up anyone they found who could possibly hear his column and warn the rebels.

The road they were now marching along on this fine, warm, darkening evening cut through the hills—the Heights of Guana—toward the village of Flushing, way up the East River, crossing the main Brookland-Jamaica highway at the Jamaica Pass.

The long column did not stay long on the road. It wheeled onto a less conspicuous wagon track that curled northward, then, just before midnight, struck across country aiming to join the Brook-land-Jamaica highway, a hundred yards below the gorge, by an inn called Howard’s Halfway House.

When the leading troops were a quarter of a mile from Howard’s, a Tory guide warned Clinton they were getting close. The general ordered the column to halt while Lieutenant Evelyn pushed on carefully with the advance patrol.

Cautiously, the patrol approached the inn, which was in darkness, and, passing it, moved onto the highway. There wasrlittle sign of the enemy’s presence until suddenly the British spotted five riders farther up the road to the east. The story of how Evelyn’s men captured the horsemen is not recorded in detail.9 It was carried out “without noise,” suggesting that the British surrounded them and had them covered before Evelyn rode out of the shadows and challenged them.

They were sent back under guard to Clinton, who interrogated them personally. Under questioning—to which they seemed initially to be astonishingly amenable—they revealed that the rebels were not occupying the pass. But as Clinton persisted with his questions about the numbers and disposition of the rebel forces, one of them complained angrily that the general was taking advantage of their situation and insulting them. “You’re an impudent rebel,” Clinton flashed back, warning that he would have them all hanged if they were not very careful.

Anyway, Clinton had got all he needed. Incredibly, there seemed to be nothing to stop 10,000 British soldiers with a large number of cannon from marching straight through the gorge and on down the road to the rear of the rebels.

In fact, the American generals had not overlooked the Jamaica Pass, but because it was so far from the lines at Brookland, they had decided to maintain mounted scouts to alert them quickly if the British approached.

But the British had captured the scouts. Clinton acted quickly—and with very great caution. On his orders, a battalion of light infantry moved forward past Howard’s Halfway House and occupied the east end of the pass. But he was not going to risk marching straight through the gorge into a possible ambush baited by five scouts who had purposely allowed themselves to be captured.

He ordered more troops to advance around the pass through the woods on the rocky hillside so that they could approach the gorge from the other side and from various vulnerable points above. Because the guides—three American Tories who lived in Flatbush —were not too sure of the way through the hills, the innkeeper was awakened and forced at pistol point to lead them along the steep woodland track known as Rockaway Path.

According to one report,10 Clinton also ordered some cannon to advance to the high ground by the same route. Trees had to be felled to make a wide enough passage for the guns. On the general’s orders, the timber was dropped with saws, not axes, to avoid the familiar noise of chopping. Then the guns and the six-horse teams were driven hard up the hill.

Meanwhile, Clinton waited with the rest of the avant-garde for daylight when he could march through the pass along the road, confident in the knowledge that the heights that overlooked it were occupied by his own troops. By that time he had sent a message back to Howe, and the rest of the big flanking column was following close behind him. By that time, too, the feint assaults at the other two points on the hills had already started.

Before midnight the column of 5,000 men, under Major General James Grant, was marching north along the coast road near the invasion beach where they had landed four days before. Among them was a regiment of American Loyalists recruited from the welcoming Tories on Staten Island.

It was Grant who during the angry parliamentary debates before Concord had assured the House of Commons that the rebels would “never dare to face an English Army.” His column was marching toward the enemy in the classical military manner—a small advance party well ahead, with scouts thrown forward and out to the side.

As they approached the Red Lion Tavern, where the Narrows road joined the Gowanus road to Brookland, the scouts came on the first rebel outposts and reported back. Grant sent forward a detachment to take the picket sentries. Unlike Clinton’s operation to the east, there was no need for secrecy. The firing would alert the rebel generals, but that was the purpose of Grant’s attack.

The column advanced past the Red Lion along the Gowanus road, which skirted close to the coast. It was two o’clock and still dark. There was plenty of time.

Grant could not keep his men on the road, for a little farther it narrowed under Blockje’s Burgh—a sheer rocky hill from which the rebels, by concentrating their fire, could annihilate advancing troops. The column turned off the road, moving through the woods onto a hill. There the advance units came under fire from a small rebel position in an orchard and checked.

American reinforcements were moving up. There were several skirmishes in the dawnlight. Several times the British fell back.

By the time Lord Stirling, rebel commander of this sector, had brought forward his troops in force, “an angry red sun,” as a rebel described it later, was already rising. The Americans formed their lines in the open on a hillside facing the main British position. Some of them were in hunting shirts, their officers distinguishable only by the ribbons they wore; others were in uniforms with the Delawares especially distinctive in red and blue. Two cannon they had brought forward opened up, and smoke drifted in the morning air into the hills.

The British deployed in a long uneven line, broken only by the gun batteries, now crashing out salvo after salvo. The firing, both the small arms and the cannon, was intense. But it was stylized conflict—the first time in the Revolution that the rebels had faced the British in the kind of formal battle formation that was customary in Europe.

In fact, the mood and character of this morning confrontation reached back centuries with the two opposing forces taunting the other to attack. For a couple of hours, as the sun rose higher, they faced each other. Several times Grant sent forward detachments across the marshy valley between them to attack one sector 01 another of Stirling’s line, but they were always fought back.

The British aim was to keep the Americans tensed, all the time awaiting assault—never quite sure that each forward move by smaller units was not the prelude to an advance along the whole front.

Stirling had no alternative but to stay where he was, stanced for defense; he could not attack, for the British outnumbered his troops by more than three to one. And Grant was waiting for the sound of the signal guns at Bedford.

At Flatbush, the Hessians, too, were listening for the noise of Clinton’s cannon. Soon after dawn the German guns had opened a heavy bombardment on the rebel redoubt constructed across the road into the hills. At seven o’clock General von Heister ordered the same kind of showy demonstration that Grant was engaged in to the west. To the pounding of his drums, his troops formed on the plain in tight, rigid ranks as though they were on a parade ground. It had much of the old-fashioned character of Grant’s confrontation—a taunting, threatening display of military might.

It was going to be a hot day, and as a special concession, this iron disciplinarian general permitted his soldiers to wear their sabers from shoulder straps instead of the tight belts at their waist, thus permitting them to open their heavy jackets.

They were a strange group of fighters, with their rigid drill formations and their extravagant uniforms. In retrospect, they seem almost Ruritanian in character. Hardly any of the officers had horses; Colonel von Donop rode “an old and solid stallion” that he had brought from Germany. But even he had to get off and relinquish it to his aide every time he wanted to send a message.

Von Donop advanced with the jaeger sharpshooters and Hessian grenadiers to the edge of the woods low on the steep hillside and opened fire on the rebel outposts through the trees. But they did not press forward very far—not yet.

The flanking column—some two miles of marching men, cavalry, cannon and wagons—curled up the steep road through the Jamaica Pass onto the main highway to Brookland and the rebel lines. As they neared the village of Bedford, Clinton was still riding with his cavalry near the head of the avant-garde.

There was a small redoubt in the village, which Clinton sent up some light infantry to capture. Then he ordered the attack signal that Grant, by the Gowanus road, and Von Heister, before Flatbush, were waiting for: two cannon fired one after the other.

Abruptly, the mood of the marching men drastically changed. Until then they had moved cautiously and quietly without urgency. Now the moment they had been building up to had arrived: the pincer movement to surround and squeeze the rebels in the hill positions and to cut them off from their fortified lines at Brookland.

Immediately, Cornwallis advanced fast with the grenadiers down the road to Brookland, intending to join up with Grant as he moved along the Gowanus road on the coast.

The dragoons and light infantry moved swiftly down the Bedford-Flatbush road, fanning out into the woods on either side.

From the other direction, the Hessians, with colors flying and bands playing, started to advance. The massed ranks on the plain split in rigid parade formation into three columns, marched to the foot of the hill and mounted up through the woods, ignoring sc far as they could the trees that interfered with their tight lines Ahead of them went Von Donop’s jaegers, moving from tree to tree, firing constantly with their forest rifles.

The rebels holding the Flatbush Pass were trapped between the advancing Hessians on their front and the British in their rear Frantically they tried to escape west, but the light infantry were already closing on them. Desperately, a group of Americans swung around three cannon they were dragging away and blasted grape at the scarlet figures approaching through the trees.

It could only be a momentary stand as the British swarmed around them. Behind them the Hessian columns had topped the hill, checked for a moment to redress their ranks under the insistent commands of their officers, who insisted on tight formation even in a woods, and then advanced again, a solid body of drilled killers, harshly disciplined to fight in unison.

The rebels fled, pursued by the British, the jaegers with their deadly firing and the Hessian columns, all bayoneting every rebel they cornered. “The greater part of their riflemen,” reported the Hessian Colonel von Heeringen, “were pierced to the trees with bayonets.”

One German column swung west to attack the flank of the rebels who were facing Grant near the Gowanus road. The remainder, with their drums still pounding the march step, pushed on through the woods behind the Americans who were fleeing toward their lines at Brookland.

Between the wooded hills and the rebel fortifications was a broad stretch of open country. It was here to one side that the dragoons, called back from the woods, were waiting in line, swords drawn, the breadth of a horse between them. In front of the ranks of cavalrymen sat the colonel. Behind him in the center of the first rank was the standard-bearer, covered by a corporal in the rank behind. Beside the commander sat his trumpeter—his means of communication.

Trumpets were employed by mounted troops to signal commands, as drums beat out orders to the infantry, and their use was rigidly regulated. There were trumpeters attached to other officers, but only the colonel’s attendant was permitted to give most calls. Just two of them—the charge and the retreat—could be taken up by the others.

The rebels broke from the trees, harried by the shooting of the jaegers, the fast-advancing Hessian columns and the British light infantry. Men streamed across the plain without formation, just running for their lives toward the fort and its protective walls. The colonel ordered the charge. The trumpet sounded. The cavalrymen moved the tips of their swords from their shoulders, holding their right wrists in the scabbard hard down on the top of their thighs, and spurred their horses.

The dragoons swept down on the fleeing rebels as the pursuing Hessians emerged from the woods behind them. Ahead of the Americans, blocking the escape route to the rebel lines, were Cornwallis and the grenadiers.

It was a massacre—within full and tempting view of their own lines, where the rebel flag of red damask11 inscribed with the word “Liberty,” still fluttered above the fort. Desperately, the fleeing rebels grouped in bunches of fifty or sixty and tried to break their way through the closing enemy lines. But the dragoons charged again and again. The Hessians, still working in ranks like automatons, advanced on them, jabbing and twisting their long bayonets. According to American complaints later, attempts to surrender were often ignored in the carnage, but the Hessians claimed that some of the rebels clubbed their arms to indicate pleas for quarter and then fired as the troops approached to take them prisoner. After that the angry soldiers became more brutal. Despite the slaughter, many prisoners were taken. Among them was General Sullivan, who was found hiding in a cornfield.

Meanwhile, the push continued. Two spearheads were racing for the rebel lines. The jaegers, “stimulated by their eager desire for combat,” as one Hessian report put it, “advanced with such vehemence that their captain was not able to keep them back; they pushed on even into the fortified works of the American camp.” These were high walls, armored with outward pointing lances, built behind a long ditch and linked to forts.

At the same time that the jaegers were advancing so fast, a column of British grenadiers was also attacking under General Sir John Vaughan. Howe had given strict instructions they were not to storm the enemy fortifications without further orders, but Clinton, who was in command of these forward units, ignored them. “I had at that moment but little inclination to check the ardor of our troops when I saw the enemy flying in such a panic before them.”

Howe was watching the battle from a different hill and saw what was happening. A staff officer rode at full gallop after the advancing grenadiers with orders to halt. General Vaughan sent back an almost desperate plea to be allowed to advance, insisting that the rebels were entirely within their power, but Howe was adamant. “It required repeated orders,” he wrote to Germain later, “to prevail upon them to desist from the attempt.”

By eleven o’clock, two hours after the attack had started, Howe’s troops lay before the rebel lines. Almost the whole ridge of hills behind them was in their hands; only the western tip, held by Stirling, was still held by the Americans, and their retreat was blocked.

Grant had delayed his attack when he heard the signal guns because he had suddenly found he needed more ammunition. His assault soon after ten o’clock, with the Hessians pressing Stirling from the east and Cornwallis approaching from the north, broke the rebel lines. Many of them tried to escape to the rebel redoubt across the treacherous Gowanus marshes, which were split by a wide creek. In an attempt to cover this desperate retreat, Stirling launched a counterattack; with only 250 men, he struck at Cornwallis’ brigade of more than 1,000.

The country was open. From the hills, the British and the Hessians could look right across the marshes to the Hudson, and as Stirling advanced, they could see guns being set up on the slopes by tired teams of American prisoners under the control of Hessian guards. Cornwallis rushed other guns to a farmhouse near the road along which rebel suicide troops were attacking.

Stirling’s move was courageous, but all it could do was to buy a little time before the British could concentrate their fire on the men trying to get across the marshes. Many of them died in the showers of grapeshot; others drowned in the creek. Some, however, got through to the rebel lines. Stirling himself was captured and gave up his sword to General von Heister.

On Howe’s strict orders, the British still made no move to attack the rebel position. At one stage, according to Clinton, there were only 800 men to hold fortifications that were so long that they would have required 6,000 men for adequate defense. They were completely vulnerable. But by that night, when the escapers had made their way behind the lines and reinforcements had been brought across the river from New York, there were more than 9,000 behind the walls.

Even this was not many, compared with the numbers of royal troops, but Howe, as he later told a parliamentary committee, was not prepared to “risk the loss that might have been sustained in the assault.” He believed he could take the position at “a very cheap rate” in casualties by approaching the redoubt carefully by trenches, dug in darkness—the classic way of storming towns under siege—and he probably could have done so if his brother’s men-of-war had been in the East River.

The wind, however, was blowing from the wrong direction, and there were no British guns to cut off communications between the redoubt and Manhattan.

While his troops lay before the rebel lines, Howe set up new headquarters in a farmhouse at Newtown, farther up the north coast of Long Island, and reported his victory to London. He claimed that there had been more than 3,000 rebel casualties—a figure that as usual was contested by the Americans, who put it at just more than 1,000. Either way, there was no doubt it was a triumph.

For two days the two armies were drenched by continuous torrential rain. During the night of August 29 the Hessian Colonel von Heeringen pushed some troops onto a hill that overlooked the rebel lines from the south. From his new position, soon after dawn, he realized that the Americans were evacuating and sent a lieutenant at top speed to warn the commander in chief. It was not the only report. The men of a British patrol had sensed that all was not quite normal. Moving closer, they had discovered that the outposts were deserted.

Howe ordered an immediate advance. But as the soldiers swarmed over the rebel fortifications and hurried toward the water’s edge, the last boatload of rebels was disappearing into the mists of Manhattan.

For the time being Washington had preserved the rebel army, but as Howe knew, the Battle of Long Island had made a deep impression on his troops—undisciplined, ill equipped, many without uniforms. By contrast with the successful rebel operations during the early months of the revolt, when the British were on the defensive, this was the first major confrontation with its new army that had been sent to America to smash the rebellion. The lesson had been severe. Desertions from Washington’s army soared.

Meanwhile, having won a battle, the Howes reverted to their peacemaking role. On their urging, the captured General Sullivan had agreed to travel to Philadelphia in an attempt to persuade Congress to send a committee to discuss peace terms, and he had succeeded.

On September 11 the admiral’s barge approached Amboy, New Jersey, flying a flag of truce. It brought a committee of three to the peace table on Staten Island: Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and another Congressional delegate named Edward Rutledge. Admiral Howe greeted them, apologized for the absence of his brother, who was on duty on Long Island, and led them between the ranks of a grenadier guard of honor to breakfast.

The conference had no chance of success. Howe’s terms of reference were limited, and the men from Congress were bitter and waspish. Only two months before, Franklin had written to the admiral in rancor over the British burning of American towns, exciting “savages to massacre our farmers and our slaves to murder their masters” which had “extinguished every remaining spark of affection for that parent country we once held so dear.”

Certainly the obstacles were great. Howe explained that he could not treat with them as a committee of Congress—which the King did not recognize—but only as “private gentlemen of influence” if they were prepared to negotiate “in that character.”

“Your Lordship,” Adams retorted quickly, “may consider me in what light you please . . . except as a British subject.”

Howe was not an aristocrat for nothing. “Mr. Adams,” he said coolly to Franklin and Rutledge, “is a decided character.”

Despite the cool response, Howe persisted with the meeting, mentioning his elder brother, who had died beside General Putnam at Ticonderoga in the French and Indian War, and saying how much the family appreciated the honor of the monument erected for him by the province of Massachusetts. “Such is my gratitude and affection for this country,” he said, “that I feel for America as if for a brother. If it should fall, I’d lament it like the loss of a brother.”

Franklin, who had discussed the issues with him so often before, was not moved by his emotion. “My Lord,” he said with feigned simplicity, “we will do our utmost endeavours to spare your Lordship that mortification.”

Howe knew what was in the old man’s mind. “I suppose you’ll endeavour to give us employment in Europe,” he grunted. The three men did not respond to this oblique reference to France but waited for Howe to continue.

The verbal cut and thrust were amusing, but they achieved nothing. Howe was there with an offer to remove grievances from colonials; the men from Congress had come to negotiate as representatives of independent states. There was no common ground. Howe, for all his gratitude and affection and “feeling for America as a brother,” went back to war.

At two o’clock in the morning of September 15, 15,000 troops in camps stretching along the north coast of Long Island struck their tents and began marching to assembly points for embarkation. As the sky lightened, five warships that had run through the fire from the rebel batteries at the mouth of the East River sailed slowly across the water toward Manhattan and anchored, broadside to the shore, off Kip’s Bay, the scheduled landing place.

At the council of war Howe had held in his farmhouse a few hours before, he had told his officers he proposed to mount a single hard thrust across the river in strength. He was planning a massive artillery barrage to cover the landing.

As usual, Clinton, who would command the assault units, disagreed with him, urging a diversion. But Howe overruled him sharply. Ruefully, after the council, Clinton assuaged his injured feelings in his notes: “My advice,” he scrawled, “has ever been to avoid even the possibility of a check. We live by victory. Are we sure of it this day? J’en doute.” His continual lapses into French must have been yet another irritation for his commander.

Soon after dawn Clinton took a boat out to the Roebuck, one of the five frigates now anchored on station of Kip’s Bay, and through his glass studied the landing point 300 yards away. What he saw did not dispel his pessimism. Unlike the case in the invasion of Long Island, there was no long sandy beach; his troops would have to clamber over large rocks, almost certainly under very heavy fire. Just behind them were rebel breastworks, trenches with earth walls thrown up in front of them, “well lined with men whose countenance appeared respectable and firm.”

Behind Kip’s Bay lay farmland—cornfields, meadows, orchards, woods. Slightly to the right the terrain moved steeply up to the Inclenberg Height on Murray’s farm. This was the first objective of the advance troops. They were to rush the hill and hold it until the followup assault waves were brought in.

To his left, Clinton could see the town of New York some three miles down the Post Road; other landing points had been fortified by the rebels, such as Stuyvesant’s Cove between Kip’s Bay and the town. As soon as the rebels saw where the assault boats were steering, Clinton surmised, the men stationed at Stuyvesant’s Cove would hurry to Kip’s Bay.

Gloomily, he returned toward the Long Island shore and met the first wave of the troop-laden assault boats coming out of Newtown Creek. The tide was flooding strongly, and Clinton feared that it would carry them upriver of Kip’s Bay, so he urged the commodore in charge of the flotilla to wait at the troopships, anchored on the Long Island side of the river, until the slack.

By eleven o’clock the tide had eased. As Clinton, still studying his target area through his glass, waited to give the order to advance he saw that the rebels had misinterpreted his purpose in holding the assault flotilla at the troopships. Clearly they thought the British were going to use the ebb, not the slack as Clinton planned, to carry them downstream for an assault at Stuyvesant’s Cove.13 Many of the men, stationed behind the breastwork of Kip’s Bay, started moving south past the windmill to reinforce the troops at the lower landing point.

The general ordered the advance, and the first wave of assault craft began to move in line abreast across the river. It was a beautiful day, the water glass-calm; the sun beat down from behind Long Island. But to the men in the boats, the sight of the rebels waiting for them on the shore was unnerving. “As we approached,” reported Lord Rawdon, who was in the same craft as Clinton, “we saw the breastworks filled with men, and two or three large columns marching down to support them.” The rebels who had hurried down to Stuyvesant’s Cove had realized their mistake and had started moving back.

The Hessians were terrified at their exposed position in the boats; jammed tightly together, easy targets for the rebel sharpshooters as soon as they moved in range, they mournfully sang hymns.

Then the quiet of the morning was shattered. More than seventy guns began crashing shot into the rocky beach at Kip’s Bay; the explosions of the repeated salvos reverberated across the water, deadening the ears of the soldiers in the boats. ‘The most tremendous peal I ever heard,” wrote Rawdon. “The breastwork was blown to pieces in a few minutes . . . and those who were to have defended it were happy to escape. . . . The columns [approaching] broke instantly and betook themselves to the nearest woods for shelter.”

As the assault flotilla went through the line of frigates near Manhattan, the boats were hidden by the smoke from the guns. When they emerged from it, there were no longer any defenders.

The craft beached, and the troops clambered over the rocks without a single shot being fired at them. They formed on the shore, crossed the Post Road and charged a group of rebels on the Inclenberg Height. But the American morale had been cracked by the bombardment. They relinquished a brass howitzer and some ammunition wagons and retreated fast. From Inclenberg, Clinton could see the main rebel force drawn up about two miles to their north toward Harlem. Ahead of them, in the middle of Manhattan, were some woods, and in the gaps of the trees, American troops, clearly afraid of being cut off by a British push across the island, were making a dash north on their way from the town.

Clinton realized that they should be checked. But his orders were to hold the hill until the supporting troops had landed, and since he only had the advance troops on Manhattan, this was clearly wise. But the slick timing of the landing on Long Island three weeks before was lacking in this second operation. Hours went by before the next wave of assault craft brought in more troops, and it was 5 p.m. before the whole assault force was landed.

Unperturbed, Howe sent one brigade south to occupy the town of New York. Meanwhile, he led his main force north up the Post Road to McGowan’s farmhouse, about two miles below the high rocky heights of Harlem, where Washington had withdrawn his army. As the British column approached McGowan’s, a detachment was ordered to advance along a branch road across the island to Bloomingdale on the Hudson.

That night, as dusk fell, the British were pitching their tents in a line right across Manhattan between the two rivers. High above them, the rebels were digging in along a narrower line between the Harlem River and the Hudson. From the front they were impregnable; only their outposts at the foot of the heights were on the same level as Howe’s army.

It had been a heady day for the British. The rebels had fled before them without making any kind of stand. In one leisurely grab, Howe had taken possession of most of Manhattan. Thus, the British sentries on duty that night in the wooded hill at Bloomingdale were surprised soon after dawn to see a large rebel patrol of more than 100 men coming through the trees. Opening fire, they sent an urgent message to General Alexander Leslie in a nearby house.

Leslie moved fast, called out the two battalions stationed on that end of the line and advanced on the rebel unit with 400 men. The Americans had dropped back to the cover of a stone wall and started shooting as soon as the British approached within range. Then they fell back again, stood at new cover and once more retreated with the British in pursuit. As the rebels slipped for safety behind their outposts at the foot of Harlem Heights, the British halted in the open on the side of a hill. Mockingly, a drummer put a trumpet to his lips and—allegedly—blew the fox huntsman’s call of “Gone to Earth.”14

It was a musical taunt that was to backlash. For Leslie’s troops were dangerously exposed, a relatively small force far ahead of their lines and close to the thousands in the rebel camp. Even when the general saw rebel troops advancing from the heights, he did not order his men to fall back, probably because the approaching column was not very big. But this fact in itself should have warned him.

The British moved down the hill to the cover of some bushes, and the advancing Americans opened fire at long range at the earliest moment they could. This, too, should have served as a warning, for their fighting technique was almost always pitched to close-range shooting.

Sudden heavy firing from a covert at the side alerted them to their danger: They had been outflanked. The rebels in front had been playing with them, keeping their attention fixed. Washington planned to surround them.

They retreated fast up the rocky hill, re-formed at a fence, shooting all the time, then fell back again to the top of the ridge. Urgently Leslie called for major reinforcements even as more Americans streamed down from the heights and some rebels’ cannon opened up.

Again the British were forced to fall back—this time into a buckwheat field—and even more troops were needed. Howe was no longer taking any chances. He sent up Lord Rawdon with a large force of British and Hessians, all running at the double with two cannon. By noon 5,000 men were engaged with the Americans.

At last, as Rawdon described it, “the rebels, finding they lost great numbers of men to no purpose, gave over the business. . . .”

It was to be the last conflict for several weeks. Again Howe stayed inactive, considering his next course of action. And Washington remained cannily on his heights.

Meanwhile, Governor Tryon had returned in triumph to Government House in New York. The Tories had welcomed the British with wild scenes of joy. The rebel flag had been hauled down and ceremoniously stamped on as the Union Jack was once again run up the town’s flagpole; Captain Duncan, who had taken a boat in from the Eagle, was chaired through the streets. And the Loyalists had enjoyed their revenge. The front doors of rebel houses, now officially declared forfeited, were marked with an R and pillaged. “And thus,” recorded the Tory Pastor Shewkirk, who believed that the British had been sent by God, “was the City now delivered from those usurpers who had oppressed it for so long.”

If God sent the British, he also sent the fire—deliberately started by rebel extremists. It burned for twenty-four hours and destroyed a third of the city before the troops and the sailors sent in from the ships managed at last to bring it under control.

On Manhattan there was a temporary lull in the war, but it was about to flare once more into violent conflict in Canada. Carleton’s shipbuilding teams at St. Johns had almost completed his ships. The enormous operation of hauling the vessels in sections past the rapids from Chambly was over.

At Crown Point, too, under Arnold’s dynamic urging, American construction teams with far fewer resources than the British had been building the vessels that were to oppose Carleton when he attacked. They could hardly hope to beat the British, whose ships were bigger and better gunned, but they could delay them. It was nearly fall. Winter would soon be gripping the St. Lawrence, making long communications impractical.

In fact, less than a week after Howe sprang at Kip’s Bay from Long Island Carleton’s homemade fleet began moving, one vessel at a time, from St. Johns up the Richelieu River to Lake Champlain.