11

NEW YORK, October 12, 1776

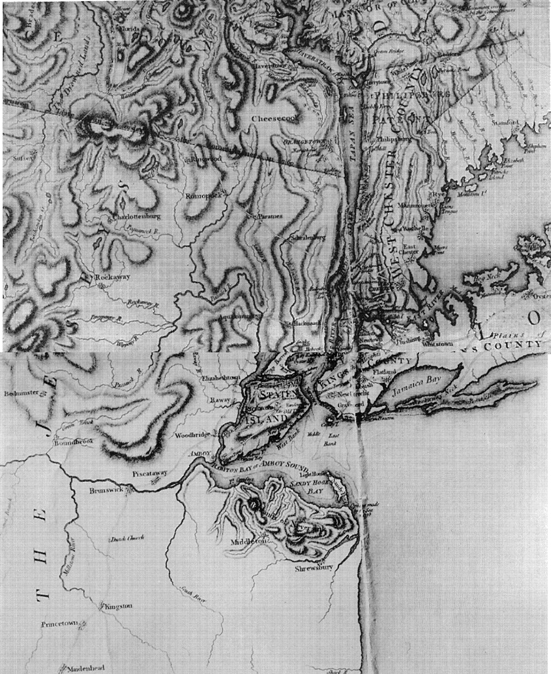

The fog came down suddenly, damp and blinding, creating crisis.1 The flotilla of flatboats and transports loaded with men and horses and guns was moving fast on the swift running tide into the turbulence of Hell Gate. At any time, except slack water, the East River was highly dangerous at this point, where it was joined by the rush of Harlem Creek as it reached for Long Island Sound, spinning whirlpools among the rocks around Montresor and Buchanan’s islands.

However, now that the fog had turned the early-morning light “into utter darkness,” as Clinton put it, the danger was immeasurably increased. It was impossible for the coxswains to see the line of buoys that the fleet pilots had set up earlier to mark the channel through the rocks.

In the admiral’s sloop at the head of the flotilla, the Howe brothers considered stopping the convoy and either anchoring or turning back, but the stream was carrying them forward so fast that with such low visibility either operation would be dangerous. So they stayed on their blind course, moving quickly along the curving narrow mile-long strip of water between the hidden bulk of Montresor and Buchanan’s islands.

Clinton was in the admiral’s sloop—as usual, his memoirs suggest, unconsulted by the Howes. In his normal role as second-in-command of the army, he would lead the avant-garde, the assault troops who would storm the landing beach, if the flotilla got safely through Hell Gate.

Even Clinton, despite his dislike of the Howes and the inevitable soldier’s disapproval of the navy, was moved to warm praise of the admiral’s skill. “By his own excellent management and that of his officers,” he recorded, “the whole got through almost miraculously, without any other loss than that of an artillery boat. . . .” In fact, Clinton was slightly in error. Two boats were caught in the whirlpools and shattered on the rocks. From one, all the men escaped alive; from the other, the gunboat Clinton mentioned, only three men out of twenty-five were drowned.

Beyond Hell Gate, the weather was clear. Then, re-formed in the two columns, stern to bows, that the Navy favored, the eighty boats moved on up the river that broadened steadily as it approached the wide waters of the Sound. It was a motley little fleet. Some of the bigger craft had sail, often just one sheet of canvas on a single mast; most of the vessels were flatboats heavy with troops, sitting huddled close together, as the oars worked with mechanically regular movements.

By eight o’clock in the morning they were nearing Throgs Neck, a narrow isthmus of land that thrust south, like a finger, from the Westchester shore. The tip, Throgs Point, had been selected for the landing, and a frigate was already waiting, gunports open, to cover the assault.

The flatboats deployed in line abreast and approached the beach. There were a few rebels on the shore who opened fire with muskets at the first wave of craft. On the frigate, a single cannon cracked out, dropping metal among the handful of defenders. A second gun fired, followed by another, shooting wide to spread the shot, just to clear the landing area; this it did. The Americans turned and hurried toward the mainland.

The troops landed without a single casualty and, as Clinton reported, “pushed for Westchester Bridge in the hopes of securing it, but the enemy had been too quick for us.”

Throgs Neck was a poor bridgehead for the Howes to have chosen, for it was divided from the mainland by Westchester Creek, which ran through marshes. There was a single bridge, and by the time the British reached it, the boards were down. Because of the marshland on either side, they could cross the creek only by going through the water in the narrow area where the bridge had been—and where the rebels could concentrate an extremely heavy fire from a redoubt constructed for exactly this purpose.

Possibly, Clinton’s advance troops could have made the crossing, but it would not have been worth the heavy casualties. The British could use the isthmus as a forward base, bringing up their supplies and reinforcements from Manhattan, before making the short jump for another landing point farther up the Westchester shore.

And bottled up though he was for the time being, Howe had achieved his main object. He had broken the stalemate that had existed for the past month since Washington had dropped back to his impregnable position on Harlem Heights, with his flanks and rear protected by water. Now the British were positioned in strength behind the rebel army—as well, of course, as still being in front of it. Lord Percy had remained on Manhattan in command of the strongly fortified front line that stretched right across the island just below Harlem from the East River to the Hudson.

Washington had no choice left. He must march north, and soon. For Howe merely had to advance across Westchester to the river for the Americans to be hemmed in with their supply routes severed.

Despite the danger, Washington did not start his retreat for six days, even though, as the disenchanted rebels who came through Percy’s line every night confirmed, he was fully conscious of the danger. Howe did not move either, for the wind, vital to sailing ships going through Hell Gate, veered to the wrong direction, then dropped altogether, halting all traffic upriver. For two days the transports lay waiting at anchor in the stream below Buchanan’s Island.

Meanwhile, the rebels had brought up guns and were bombarding the British on the isthmus. Howe’s position was uncomfortable, and at 5 a.m. on October eighteenth, his troops sprang for another bridgehead, three miles to the north.

A battery of six guns on Throgs Neck opened up, and the shot whistled over the water to pound the new landing beaches at Rodman’s Neck—another isthmus, but this time with a link to the mainland uncluttered by creeks or marshes.

The two columns of flatboats filled with the avant-garde were led by two frigates, which turned off and opened up with crashing broadside salvos at close range as they approached the shore.

The fields, dotted with trees and patchworked by stone walls, stretched to the water’s edge. There was little sign of opposition while the ground was battered with solid shot and spurted into sprays of dirt by the shells. But as soon as the barrage was lifted to allow the troops to land, rebels, who had been crouching behind the cover of the walls, started firing.

Clinton in the command boat tried to assess their numbers and even considered whether he should stop the landing. “But,” he recorded, “as I was certain they could not be in any great force, I ordered the debarkation to proceed.”

As the assault troops leaped out of the boats and splashed onto the shore, the rebels dropped back fast. The British advanced quickly, making for the main coast road that linked New York with Connecticut—what Clinton called “their great communication.” Because the route lay under a hill on their right that was marked with heavy cover, Lord Cornwallis led a detachment into the high ground. While the main column moved forward cautiously below, grenadiers and light infantrymen routed waiting rebels from their positions behind stone walls and farm outbuildings; the sharpshooting jaegers stormed a wood that lay ahead.

Though there were pockets of fierce fighting, by night the British lay in force on each side of the coast road. Cornwallis wan on the hillside guarding the lines of communication with the landing beaches, where all day long the boats had been ferrying men and equipment from Throgs Neck.

All day too, 12 miles away on the other side of Westchester near the Hudson, the rebels had been moving north toward White Plains.

Later Howe was criticized because he made little attempt to harry the rebels on the march. Clearly he lost an opportunity, but as always, he hated to make aggressive moves unless he could do so from a firm position of strength. For nearly a week the British prepared carefully, broadened their base, spread out to New Rochelle and set up an outpost a little farther north along the Sound at Mamaroneck.

Meanwhile, although Washington moved most of his army north, he left a large garrison of nearly 3,000 men at Fort Washington, a big redoubt in the seemingly impregnable craggy heights of the northern tip of Manhattan. The fort was a key point in the rebel defense system of the upper part of the Hudson. From the foot of the sheer cliff face beneath the fortification, a line of sunken ships formed a boom across the river to Fort Lee, also set in a fine natural defense position more than 100 feet above the water on the New Jersey shore.

The guns of the two forts could rake any royal ships that moved upriver from the fleet anchorage. Even so, British frigates often ran the gauntlet and early proved that they could break through the boom.

On October 25, twelve days after he had moved his first assault troops north through Hell Gate, Howe ordered Clinton and the avant-garde to advance to Eastchester Heights, just three miles from the rebel lines below the village of White Plains. In the dawnlight they marched from New Rochelle in two long columns of infantry, guns and cavalry: one on the main road that led to White Plains, the other along rough wagon tracks that curled between the fields and through the woods of the hills to the west.

They had to travel only six miles, and when they camped on the timbered slopes, their forward outposts were so close to the American pickets that the sentries on both sides could hear each other.

Washington responded carefully. His army had been waiting on both sides of the Bronx River, which, snaking as it did across the plain and, at one point, turning sharply west, could be a most important factor in battle. Now he moved most of his men to the eastern bank, the side from which the British were most likely to approach. Behind his lines lay the mountains, and in the mountains at Peekskill lay the rebel supply magazines.

Following his usual uninvited custom, Clinton sent his battle proposals to his commander, who was still at New Rochelle with the main part of the army. He favored a reconnaissance in force, since they did “not know the ground about White Plains,” followed by a feint retreat, a secret return by night and a dawn attack. Clearly he was hoping to repeat his successful strategy on Long Island.

Howe did not reply for forty-eight hours, and when he did, he merely ordered the reconnaissance. Clinton reported that Washington had chosen his position well. With his main lines just south of White Plains, he had mountains protecting his left flank and the Bronx shielding most of his right wing. Furthermore, any time he chose, he could retreat north into the safety of the pass behind him.

That night Howe gave orders that the whole army would advance to White Plains the next morning. His second-in-command was horrified; apparently it was to be a frontal attack on an enemy who was extremely well positioned. In fact, the evidence suggests that Howe merely planned to get his troops within sight of the enemy and to figure out his tactics from there. At least, on the plain he had room to move.

His strategy may have been a bit vague, but he had a beautiful day in which to execute it. The sun shone brightly from a fine clear sky as Clinton’s two columns—one on the road, which he led himself, and one in the country on the left that was advancing along a wagon track so narrow that they had to march in file—moved down the Eastchester Hills, thick with trees nearly bare from the fall, toward the plain. Behind him, the main body of the army was marching from New Rochelle.

Because the road curled downward through hills, Clinton’s view of the plain was obscured. But Howe was watching the enemy’s movements very carefully; for this reason, he saw the danger that was out of Clinton’s line of vision: A large detachment of rebels, alerted presumably by their scouts, was moving fast up the road along which the advance column was approaching.

An aide galloped up to Clinton past the long line of marching men with a warning from Howe that the enemy was forming to attack him as soon as he appeared on the plain. Inevitably, Clinton disagreed with his commander’s interpretation. “I was certain,” he wrote later, “the instant they discovered my column, they would retire.” And he planned that as they did so, he would cut them off from the rest of the rebel army.

On the right of the road was a hill that screened the plain.2 Clinton halted his column while Cornwallis broke across country around the eastern side of the hill with cannon and some light troops. His orders were to take the rebel advance guard in their rear. Clinton ordered the advance to continue, and the column moved on down the road that skirted the hill onto the plain.

The rebels were waiting in their favorite type of defense position—behind stone walls. And as usual, they held their fire until the Hessians, who were in the lead, came very close.

The clash did not last long, but it was intense. Clinton halted the column, while a detachment of Hessians and jaegers swarmed off the road to attack the rebel positions. The Americans fell back, field by field, firing from each line of walls they came to as they retired. When Cornwallis’ cannon opened up from their rear, the conflict ended abruptly. The rebels could not retreat to Washington’s main lines, but they had an alternative escape route. Pursued closely by the Hessians, they splashed through a ford across the Bronx and headed for the cover of some woods on the other side of the river.

Meanwhile, the skirmish over, Howe’s army descended from the hills and marched in three columns across the plain toward the main rebel lines. “Its appearance was truly magnificent,” a watching rebel officer, Otto Hufeland, reported later. “A bright autumnal sun shed its lustre on the polished arms; and the rich array of dress and military equipage gave an imposing grandeur to the scene as they advanced in all the pomp and circumstance of war.”

The British halted while Howe held a conference with his senior officers in a wheatfield. Certainly, as Clinton had warned him, he had a problem. Above him, under the mountains, was the wall of beaten earth and stones that marked the rebel front line—reaching from the Bronx on the west to a steeply wooded slope and a lake on the east.3 Beyond the fortifications, the British general could see the town of White Plains—clapboard houses, gathered around a courthouse and a steepled Presbyterian church.

About half a mile across the river to his left was Chatterton’s Hill, a long high ridge of fields thickly timbered at its lower levels. Because it overlooked the town and Washington’s lines, it was an obvious place for the British to set up an artillery battery; that was why a big rebel working party was now busy fortifying it.

Howe regarded the hill as the first objective in his tactics—for he could then advance against the main American position under the cover of a very heavy barrage—and gave orders for it to be taken.

While most of his army sat down on the ground in ranks to wait until they were needed, horse teams hauled a dozen guns onto a small hill that faced Chatterton’s across the river. The twelve guns opened fire almost simultaneously, terrific explosions echoing back off the mountains like continued peals of thunder. Meanwhile, a mixed British-Hessian detachment of infantry was ordered across the river.

For once, presumably since the scene of action was so limited, Howe and his frosty second-in-command were together as they watched their troops advancing under fire toward the woods that covered Chatterton’s lower slopes. It must have brought back memories for Howe, for tactically the situation was not all that different from the conditions that had faced him on Bunker Hill. Two British regiments were moving forward up the hill in line abreast, as indeed they had at Bunker Hill. A wave of rebel fire checked them. Coolly, their commander ordered them to form in column, so as to present a smaller target, and once more they advanced toward the bank of trees. “The instant I saw the move,” recorded Clinton, “I declared it decisive.” The tactic was carried out confidently and professionally, and the attacking column was soon progressing fast up the hill under very heavy fire. Then suddenly, Clinton saw the whole maneuver collapse.

“When the officer had marched forward about twenty paces, he halted, fired his fuzee [a small musket] and began to reload (his column remaining during the time under the enemy’s fire), upon which I pronounced it a ‘coup manque,’ foretelling at the same time that they would break.”

Vital seconds went by while the officer reloaded and the rebels kept firing from the trees at the waiting column. Soldier afte: soldier dropped in the ranks, which formed promptly to fill the gaps. At last, as Clinton forecast, they broke and ran for cover. “If the battle is lost,” he remarked to Howe, “that officer was the occasion of it.”

“I had scarcely done speaking,” Clinton wrote, “when Lord Cornwallis came up with the same observation.”

Clinton’s comment was barbed, for he had long urged that officers should not carry fuzees. Their role, as he saw it, was to command, to manipulate the fighting machine—not to take detailed part in it. It was one of Clinton’s many theories that Howe did not act on, and indeed it was by presenting bayonets fixed on fuzees that officers had been able to force their men to form as they were running in panic toward Lexington from Concord.

At Chatterton’s the setback did not make much difference. I was certainly no repeat of Bunker Hill. The British re-formed and advanced with the Hessians. Another contingent attacked the rebe flank from the other side of the steep slope and quickly took possession of the summit.

Howe had taken his artillery position, but, as Clinton put it “after this little brush, we paused a while.” As well they might, for the problem of how best to attack White Plains was clearly very difficult. For two days, they waited. Howe had called up reinforcements, while at his request Clinton had ridden through the woods on the west side of the Bronx to reconnoiter the possibility of attacking the rebels on their right wing or even their rear. He suggested an attack plan with fairly sophisticated use of the whole front but weighted against the rebel’s left wing on the river, but even he was dubious since “the enemy had a very strong position in the gorges of the mountains behind them.”

Howe, as almost always, altered Clinton’s plan. The attack which was sure to be costly in British lives, was scheduled for the morning of October 31. The evening before, however, the weather changed for the worse—to torrential rain, followed by snow. The waters of the Bronx, flooding down from the hills, rose higher, breaking over the banks at points. At two in the morning Howe summoned Clinton to his tent to consider if in view of the altered weather, and in particular the swelling river which some troops would have to cross, he should change the attack plans. Clinton, though disapproving of Howe’s alterations to his suggestions, did not think the rain was a reason to abandon them. “While the river remains passable to the left,” he told his chief with feigned respect, “I shall be ready to obey Your Excellency’s commands whenever you think proper to order the attack.”

As Howe studied his maps in the candlelight, he must have wished he had another man as his second-in-command—someone a little less cool, less remote, less critical. However, he decided that the attack should proceed as planned.

In the early-morning darkness the troops who were to strike the center of the rebel line were already advancing through the wet when they discovered that the fortifications were no longer manned. The Americans had evacuated their camp and retired into the gorge a mile above White Plains.

Once more there was a stalemate. The rebel flanks were now enclosed by hills. The only attack plan open to Howe was uphill on their front, which would be extremely hazardous, and even if it succeeded, the Americans could easily drop back farther into the hills.

It was, however, a very different stalemate from the situation that had existed only two weeks before, when the rebels had been entrenched on Harlem Heights. Apart from the garrison the American commander had left at Fort Washington, the British now controlled most of Long Island and the whole of Manhattan, Staten Island and Westchester. There was little to stop them from striking across New Jersey, a province in which the Loyalists were particularly numerous. From the north, reports were filtering through that Carleton had defeated Arnold and now controlled Lake Champlain. Accounts of deserters suggested that the morale of Washington’s men was appallingly low. “It is a fact,” wrote Lieutenant Frederick Mackenzie in his journal, “that many of the rebels who were killed in the late affairs were without shoes or stockings. . . . They are also in great want of blankets. The weather during the former part of the campaign has been so favorable that they did not feel the want of those things, but in less than a month they must suffer extremely if not supplied with them. Under all the disadvantages of want of confidence, clothing and good winter quarters . . . it will be astonishing if they keep together till Christmas.” Also, the strain was aggravating the old regional antagonisms that were always simmering below the surface of the rebel forces. “The people from the Southern Colonies,” recorded Mackenzie, quoting a deserter, “declare they will not go into New England, and the others that they will not march to the southward. If this account is true in any degree, they must soon go to pieces.”

Howe was fully conscious of Washington’s difficulties. He knew, too, as he had known twelve months before when the rebel general was blockading him in Boston, that the year’s term of service for which many of his ragged men had signed on was due to finish at the end of December. The low morale and the cold early winter nights were hardly likely to encourage reenlistment.

It seemed that the Revolution was almost over, but unlike most of his senior officers, Howe did not believe there was time before the end of the year to strike the final blow. For this reason he gave orders for a force to be prepared to take Rhode Island, which, unlike New York, which often iced up in the cold weather, had a deepwater harbor that would provide the British fleet with a base its ships could use throughout the winter and a springboard for a strike next year through New England, which featured in Howe’s planning. In command of the expedition—probably so that he could get a bit of peace—he placed Clinton.

Before daylight on November 5 the main part of Howe’s army was on the march south along the coast road near the Hudson that the rebels had used to escape north from Harlem. He had already ordered the newly arrived Hessian General Wilhelm von Knyphausen, who was waiting at New Rochelle, to attack a minor rebel position at Kingsbridge—the link between Manhattan Island and Westchester. Now he was going to storm Fort Washington.

The assault was certain to be formidable, but for once Howe’s intelligence, normally a great problem for attacking commanders, was exceptionally good. Three nights before, on November 2, a young rebel officer named William Demont had approached one of Lord Percy’s outposts under Harlem Heights and asked to be taken to headquarters. He was, he told the incredulous interrogating officers, adjutant to Colonel Robert Magaw, who commanded Fort Washington and, as a result, knew all the defense arrangements. He had with him maps showing the outposts, the fortifications and the planned disposition of the rebel defenders to withstand attack.

Acting with his usual caution, Clinton took ten days to prepare his attack. By November 15, he was ready. On the Westchester bank of the Harlem River, facing Mount Washington was a battery of twenty guns and howitzers. Gathered near them in the stream was a flotilla of flatboats that had been brought up the Hudson in darkness two nights before under the guns of the fort.

On the bare chance, however, that he could avoid a battle altogether Clinton sent Lieutenant Colonel Patterson, the officer the Howes had sent to parley with Washington before the invasion of Long Island, across Kingsbridge carrying a white flag. With him were three other officers. As they rode slowly up the hill toward the fort, they were met by a rebel officer, to whom Patterson handed a summons to surrender or, under the rules of war, the entire garrison would be slaughtered.

Magaw, the rebel commander, sent back a defiant message refusing the offer. “Give me leave to assure His Excellency that, actuated by the most glorious cause that mankind ever fought for, I am determined to defend this post to the very last extremity.” So the battle was on.

The early-morning mist still lay over the Harlem River as, just before seven o’clock, Howe’s big battery of guns on the Westchester bank opened fire from the north, supported by broadsides from a frigate anchored in the Hudson. At the same time, Percy’s cannon began pounding the lowest rebel line on the southern slopes; then under the cover of the barrage, his troops advanced north along the Kingsbridge road that cut upward through Harlem Heights.

The narrow craggy triangle of Mount Washington was protected on two sides by water, by the Hudson on the west and by the Harlem River on the northeast. Three rows of fortifications, stretching in layers between the rivers, protected the steep approach from the south through which Percy was now advancing.

In fact, the southeast was the obvious direction from which to mount the main weight of attack, for the slopes near the Harlem at this point were easy. But this sector, like the river itself, was dominated by Laurel Hill, on which the rebels were installed in strength. Howe, who had placed himself with Percy’s troops, had planned a simultaneous four-pronged strike on the fort. The advance from the south was technical—a breakthrough of the first defense line, which the rebels abandoned quickly, followed by an advantageous placing of the guns. There, the British extended their line to the Hudson and waited, with their artillery firing, for the impact of the main assault: by the Hessians from the north.

The Hessians, too, were waiting. Earlier, under the cover of the artillery barrage, Lieutenant General Baron von Knyphausen had led his force across Kingsbridge from Westchester. Now with their field cannon set up, 3,000 whiskered men, in their tall miterlike caps and their range of colored coats, were poised to attack the fort from the north the moment their commander received the final order from Howe.

But a sophisticated assault plan had been marred by the naval advisers. For another strike force, the light infantry and grenadiers, should have crossed the Harlem farther downstream in flatboats to capture Laurel Hill from the rebels and stop their cannon from threatening yet another landing even lower down the river by the Highlanders.

But the plan, as Engineering Lieutenant Archibald Robertson put it, “did not work immediately, for want of tide not serving, which had not been duly attended to.”

The tide did not “serve” until just before noon.4 Then, as the Westchester guns plastered Laurel Hill with salvo after salvo, the assault force in the boats crossed the Harlem under very heavy fire and charged up through the trees toward the rebel battery that commanded the river.

At the same time, the Hessians swarmed up the rocky, timbered north side of Mount Washington, branching into two columns. The frigate on the Hudson was pounding the outer defense lines above them. Even so, the rebels were fighting desperately, flaying the approaching Germans with musket shot and grape from an outpost, as they clambered up the incline, grabbing bushes to drag themselves over rocks.

It was a short but violent battle. By one o’clock, as their drums pounded, the Hessians on the north side of the mountain were almost at the summit. “Forward!” yelled Colonel Johann Rail, who was leading this attack; cheering, they broke through the rebel line and charged on the fort.

By then the light infantry had taken Laurel Hill. The Highlanders had landed. Percy was attacking hard on the south side. Soon the fort was ringed by Howe’s forces, and the rebels had been forced to drop back from the outpost within its walls.

Magaw’s position, with more than 2,000 men crowded into what was little more than a big redoubt, was hopeless. If Howe ordered his cannon to shell it, there would be a massacre.

Accompanied by a drummer beating the truce, a Hessian officer approached the fort with a white cloth tied to a musket and demanded surrender. Magaw asked four hours to consider terms— which would have given them almost until darkness with its obvious possibilities of escape—but Von Knyphausen granted them half an hour. Soon afterwards, Howe arrived and promptly sent in a sharp message that if they wished to survive they would surrender immediately, with no terms other than a promise of their lives and their baggage.

At four in the afternoon, Magaw gave up his sword, and 2,300 rebels filed out of the fort under the guard of Howe’s soldiers.

It was a spectacular victory, symbolic because it cleared the rebels from their last foothold in New York and dramatic because of the enormous number of prisoners—men Washington was to need very badly.

For once the careful British general did not rest too long on his success. By daylight of November 20 the familiar two lines of boats loaded with men and cannon were moving across the Hudson. Teams of sailors hauled the guns up a steep 600-yard path that reached from the waterside up the high cliffs to New Jersey’s Palisades woods.

Four thousand men under the command of Lord Cornwallis advanced on Fort Lee, which lay across the Hudson opposite Mount Washington. They did not have to take it by storm, for the rebels had evacuated it only minutes before Cornwallis’ forward troops reached the walls; the Americans’ kettles, so Howe reported somewhat jauntily to London, were still simmering over the fires. Cornwallis ordered the pursuit of the fleeing garrison, and more than 100 rebels were killed or taken prisoner before the chase was called off. The capture of the two forts gave the British 146 guns and enormous supplies of rebel ammunition and flour.

The British strike south was an obvious move, but it was defensive, not offensive, as it later seemed, designed to secure the rich New Jersey farmlands as a foraging area for the army during its winter on Manhattan. Howe, as he made clear in a letter to Germain in September, had regarded his campaign of 1776 as over before he made his plunge north through Hell Gate. Only the exceptionally fine fall weather influenced his decision to force Washington off Manhattan, where he would have been an uncomfortable neighbor, and, if possible, to tempt him to battle. Events, especially the easy capture of Fort Washington, had gone far better than the British commander had expected, but when he ordered Cornwallis across the Hudson, he certainly had not the slightest intention of driving for Philadelphia.

Clearly Washington completely misinterpreted Howe’s thinking and, in so doing, very nearly destroyed the Revolution. So that he could check a British move south, he had crossed the Hudson farther north with 5,000 men and now lay waiting at Hackensack, only a few miles southwest of his abandoned fort. But just in case the British struck north through the hills or west, he had left General Charles Lee with 5,000 troops at North Castle, just above White Plains, and posted yet another smaller force far up in the mountains at Peekskill to guard his magazines.

The rebel commander had made a grave planning error. Obviously, he was thinking in terms of checking any British attacks in any direction, but with the imminent arrival of New York’s freezing winter it would have been extraordinarily risky for Howe to have mounted this kind of extensive attack, which would inevitably have involved long and vulnerable communications.

And why should Howe take any risks? The Revolution was already in the death throes, although it would probably take one more campaign in 1777—New England, in particular, needed attention—to settle it completely. Steadily he was extending the territory under British control on a firm and properly governed basis. Most important, as he well knew, Washington was in bad trouble; repeated British victories, capped by the ease with which they had taken the supposedly impregnable mountain fort, were fast sapping the morale of men already distressed by inadequate clothing and equipment. Desertions were soaring.

Now Washington had weakened himself even more by dividing his force, while Howe was free to ship across the river as many troops as he felt the situation demanded. The rebel commander was in no position for a major confrontation with the force of British and Hessians, buoyant with success, that were now advancing on him. Only at this point, as Cornwallis realized the true extent of Washington’s predicament, did the idea of striking for Philadelphia begin to be entertained.

For a night after taking Fort Lee, Cornwallis’ troops were halted because the rebels had destroyed the bridges over the Hackensack River. But by the next morning his advance corps were across it, and the rebels were in full retreat south toward Newark.

As he ran before the British, Washington’s only hope seemed to lie in finding some point where he could make a stand, though this could hardly be successful unless Lee joined him with the troops from North Castle, a rendezvous Cornwallis was now determined to intercept, or unless he could rally sufficient New Jersey militia.

On Manhattan, waiting to leave with his 6,000 men to take Rhode Island, Clinton saw the possibilities that the new situation had opened up.

“Lord Cornwallis’ success in striking a panic into and dispersing the affrighted remains of Mr. Washington’s army was so great before I left New York,” recalled Clinton, “that I had little doubt, and told Sir William Howe so, of His Lordship’s overtaking them before they could reach the Delaware. . . . I was much concerned to find his expectations not quite so sanguine.”

Howe’s plans had not changed. He was still merely intending to take East Jersey for the foraging, holding it with a string of posts until the spring. When he explained this to his peevish second-in-command, Clinton was astonished. “I took the liberty,” he wrote, “of cautioning him against the possibility of its [the chain of posts] being broken in upon in the winter, as he knew the Americans were trained to every trick of that country of chicane.” Then Clinton suggested that the Rhode Island expedition should be temporarily postponed so that the troops, already embarked on the transports in the harbor, should be pushed up the Raritan River, where they could cut off Washington’s retreat.

This was such an obvious move that Howe’s failure to act on it, for which he was later attacked bitterly, provided ammunition to his enemies, who were alleging that he was siding secretly with the rebels. But his thinking was fixed firmly on the final blow the next year, and Rhode Island, ideally positioned as it was for attack on the New England mainland, was central to this: He was not being diverted. He rejected Clinton’s suggestion, and on December 1 the assault fleet passed by the mouth of the Raritan and headed north into the winter buffeting of the Atlantic.

By then the British pursuit of the rebels in New Jersey had become a chase. From Hackensack Cornwallis marched to Aqua-kinunk on the Passaic River, then turned south and advanced down the bank toward Newark. Intelligence had come in that the rebels planned to make a stand at Newark, and he moved carefully in the two columns, one advancing through the hills, that the British always employed when they expected trouble. In fact, the rebels stayed in the town for several days, but as soon as Cornwallis’ advance guard approached on the morning of November 28, they retreated without even leaving any men to harry them with a few cannon shot.

As Cornwallis learned with satisfaction, Washington had tried to rally the New Jersey militia but had failed abysmally; not one man answered the call. He had no alternative but to continue in full retreat in a desperate attempt to save his small force of demoralized men—at least until Lee could get to him with reinforcements. And Cornwallis’ dragoon patrols, who were scouring the routes that Lee might take from North Castle, reported no signs yet of the approach of this force.5

Even more encouraging for Cornwallis was the fact that Washington was traveling through country where many Loyalists had long been waiting impatiently for the defeat of the Revolution. Now, like the Long Island Tories three months before, they took their revenge for the persecution they had suffered. Whig homes were plundered and set on fire; Cornwallis got all the information he needed about the movements of the fleeing rebels.

After entering Newark, Cornwallis stepped up the pace. The next day his advance troops were through Elizabethtown and probing the approaches to Rahway, only a few hours behind Washington’s men. On December 1 the British marched 20 miles through pouring rain over roads that were thick with mud, and caught up with the rebels at New Brunswick. There the rebel rear guard did open up with their cannon to hold off their pursuers until the bridges over the Raritan had been destroyed. The jaegers in the advance corps attacked the demolition men, but they were just too late.

Despite this, Washington and his column of depressed and bedraggled men now seemed utterly vulnerable. The bridges would be fast repaired by the army’s engineers; the rebel commander had not been joined by Lee and the reinforcements; he had not raised the militia. There seemed nothing to stop the British from crossing the river and savaging him—nothing, that is, except Cornwallis’ orders to halt at New Brunswick which, positioned as it was on the natural line of the Raritan, had been selected as a key point in Howe’s planned chain of posts.

Also, the British needed a pause. Their line of communication was becoming dangerously long for what was still a relatively small strike force. Cornwallis had now had reports that Lee was crossing the Hudson. Because of the swift British advance in the rain through very heavy going, food and fatigue were becoming a problem. “As the troops had been constantly marching ever since their first entry into the Jerseys,” he testified later, “they had no time to bake their flour; the artillery horses and the baggage horses of the army were quite tired. . . . We wanted reinforcements, in order to leave troops for the communication between Brunswick and Amboy.” Amboy was the nearest Jersey town to Staten Island, which the British already held.

As Cornwallis saw it, there was no need for haste, no “considerable advantage” if it meant taking risks—as it did. For five days the British stayed at New Brunswick while Washington moved on south toward the Delaware. On December 6 Howe arrived at the town with more troops and gave orders for the pursuit to continue.

The next day the British advanced cautiously toward Princeton, their reconnaissance parties probing the Rocky Hill Pass, where they had been warned the rebels were posted in strength. But there was no opposition, and they moved on toward the Delaware River town of Trenton. Again, as the advance guard entered the town, they saw no sign of Washington’s men until they fanned out along the banks of the river; then the noisy flashes on the far shore, sending shot screaming over the water, revealed their positions.

The British searched Trenton for boats and sent parties up the Jersey bank of the Delaware to seek them in the other river towns, but the rebels had moved them all across to the Pennsylvania shore. It was not an insuperable obstacle. The army was used to crossing water at short notice. Almost certainly they could have made rafts; the boards of half-completed craft were in the timberyards of Trenton and the other towns. But by the time the Delaware had been scoured for craft it was December 10, only a couple of weeks to Christmas. The nights were cold. Ice was swirling down the river. It was not the weather for campaigning.

The year had ended far more successfully than Howe two months before would have believed possible. He had battered the rebel army to a point of near disintegration. The British now controlled a large area on the eastern seaboard and the whole of Canada. Following the Howes’ latest offer of the royal pardon, New Jerseymen were flocking into the towns to sign the oath of allegiance to the King—at the rate, so Cornwallis later testified, of 300 to 400 a day. Congress was so anxious about the presence of British troops on the Delaware that it had left the Pennsylvania capital for safer quarters farther south. As president, John Hancock had issued a desperate panic appeal to Americans to save Philadelphia, justifying Washington’s retreat as technical and asserting “that essential services have been already rendered us by foreign states. ...”

It sounded pretty shrill coming, as it did, on top of other dramatic moves by the rebel leadership to raise men to fight a revolution for which many Americans did not feel much enthusiasm. One province had been forced to introduce compulsory conscription to make its contribution to Washington’s army; two others had set up incentive schemes. There were reports that some recruits had been driven into battle at gunpoint. In addition, the weakening resolution in the conflict with the King was revealed in the narrower voting on resistance motions in their provincial congresses.

The Howes were not just waging a military war—which they were clearly winning—they were putting down a revolution inspired by militants. That was why they kept proclaiming the King’s offer to redress the grievances of his colonial subjects, and it was fairly obvious that they were winning the political battle as well.

To cap it all, a dragoon patrol had just captured Major General Charles Lee, second-in-command of what was left of the rebel army and, after Washington himself, the most experienced military leader they possessed. To the British Lee was in a very special category, for he was an English soldier who had served with credit in Europe in the British army, in which, as Howe understood it, he was still technically an officer.

If there was any doubt about the punishment that would be meted out to the other revolutionary leaders, there was little speculation in the minds of British High Command about the fate due to Lee. He was a traitor. Even before Lexington, Gage had been instructed to arrest him on the specific orders of the King. The only thing that deterred Howe from ordering his immediate court-martial, which would inevitably sentence him to death for treason, was Lee’s insistence that he had formally resigned from the British army. The commander in chief wrote home to Germain for legal guidance, pointing out acidly that his exchange-of-prisoner arrangements with Washington did not extend to deserters.

Meanwhile, he decided to suspend offensive operations until the spring. He gave orders for the chain of posts he had mentioned to Clinton to be set up across New Jersey for the winter, though following the British advance to the Delaware, this reached to Trenton, which was farther south than he had originally intended. Eighty miles long it was, Howe conceded to Germain, “rather too extensive,” but he was relying on “the strength of the corps placed in the advanced posts” and on the evident goodwill of the New Jerseymen.

Clearly, under Howe’s policy of steadily broadening the territory he controlled, it was advisable to hold Jersey. Also, the Loyalists needed British protection; if he withdrew his army they would be badly persecuted by the rebels, not encouraging the loyal Americans in other areas to declare themselves.

Obviously, Trenton was the most exposed of the posts, but it was protected by a broad river and was manned by a Hessian corps that had proved themselves in battle and that was commanded by an officer who had led the assault on Fort Washington very ably. There were two other posts nearby, at Bordentown and Princeton, which could send quick aid if necessary.

Only one factor must have made the general pause before completing his plans: Even though Washington was across the river in Pennsylvania, New Jersey was by no means settled—a situation that was aggravated, according to disgruntled Loyalists, by the inevitable indiscriminate plundering of Howe’s troops, who were not too concerned about the political sympathies of the owners of the homes they pillaged.

Certainly, roving rebel bands were attacking sentries and small bodies of troops that might be on the move between posts. They were raiding British supplies on some scale. On December 11 a militia company swooped on Woodbridge, at the center of the British line, and drove off as many as 400 head of cattle and 200 sheep. Only the next day, because of the hostility of the “peasant canaille,” as one Hessian officer called them, Howe issued an order that any un-uniformed men who fired on his soldiers would be “hanged without trial as assassins.”

However, he was clearly in a genial mood. It was the end of a campaign. He was on his way to his mistress in New York, which, with Philadelphia, was the nearest the provincials had to a sophisticated town on the European pattern. Christmas on Manhattan would be a welcome change after weeks in the fields.

It was two o’clock on the freezing morning of December 27 when, so recorded Engineering Lieutenant Archibald Robertson, a rider galloped down the darkened main street of Amboy, the New Jersey port that lay just across the mouth of the Raritan from Staten Island. He carried an express from General Grant at the New Jersey regional headquarters at New Brunswick that was alarming: The rebels had crossed the Delaware and attacked Trenton. The commander, Colonel Johann Rail, and his Hessian garrison of more than 1,000 men had all been killed or taken prisoner, except for only 53 men who had escaped.

It was not the attack so much as its total success against experienced troops that was so shocking to the British officers who learned of it as the news was carried north. Rall had broken with traditional defense techniques; he had built no fortifications.

Another messenger left Amboy immediately for New York to alert Howe. For although the rebels had retired across the Delaware, it was obvious they would soon return.

Cornwallis, who hurriedly canceled last-minute plans to return to England, was ordered into New Jersey. On New Year’s Day he rode 50 miles to Princeton, which, according to strong rumors, was Washington’s next target. By then the Hessians had dropped back there from Bordentown, and big reinforcements had marched south from New Brunswick.

Cornwallis arrived that night to find the town tensed for attack. That morning there had been a skirmish as the rebels, already in Trenton, had approached the pickets. He wasted no time; immediately, in the darkness, he pushed forward his outposts. Before daylight he was marching in heavy rain through the thick mud of the Trenton road with more than 7,000 men and an artillery train of twenty-eight guns. Strong flanking columns made their way through fields on each side.

Behind him in Princeton, he had left a rear guard of 1,200 men. Now, as they passed through Maidenhead on their way south, he left a garrison to hold the village.

At ten o’clock in the morning, a mile south of Maidenhead, his advance corps came on Washington’s outposts. The rebels contested the approach to Trenton very fiercely, and the heavy going slowed up Cornwallis’ main body. It was not until late afternoon that the British were in the town, still moving forward slowly under heavy musket fire from the cover of the houses.

Washington had set up his main defense line on a ridge just outside Trenton to the south of the Assumpink Creek, which flowed through the town into the Delaware. By the time the British had fought their way to the creek daylight was fading.

Cornwallis discussed tactics with his senior officers. One of them, Sir William Erskine, according to an unofficial source, favored a night attack across the creek, but the others, arguing that the rebels were trapped against the semifrozen Delaware, advised a morning assault in daylight.

However, the rebels were not trapped. The river and the creek formed two sides of a triangle, and Cornwallis, according to the ever-critical Clinton, who called his failure to act “the most consummate ignorance I have ever heard of [in] any officer above a corporal,” should have pushed troops across the creek to form the third which would have boxed in the rebels. Instead, Cornwallis decided to wait until dawn. All night, fires marked the three-mile rebel line on the hill on the other side of the creek. The British pickets could hear the sound of spades as their working parties built more entrenchments.

One young ensign, so Clinton noted with disgust, thought he saw the rebels on the move as “Washington . . . filed off before his fires and not behind them.” But if he reported his suspicions, no one took any notice.

By sunrise it was obvious that the rebels were no longer there. And the distant sound of cannon fire from the direction of Princeton indicated very clearly where they were.

There were two roads from Trenton to Princeton: the main route through Maidenhead, along which Cornwallis had advanced the previous day, and a far longer back road through Allentown. It was this that Washington had taken during the night.

Cornwallis ordered an immediate march back to Princeton on the main road. Very soon he learned on the route that his rear guard in the college town, greatly outnumbered by the rebels, had been badly mauled. Taken by surprise, one group had fought their way through the rebels to escape to Maidenhead. Others had fled along the road to New Brunswick. A number had been taken prisoner.

In tactical military terms, Cornwallis faced crisis. As he was only too aware, if the rebels made a quick strike north to New Brunswick, only a few hundred British troops remained to defend the magazines and the military chest that contained £70,000 in cash.

By late morning his advance corps had passed through Maidenhead and had checked on the hill overlooking Stony Brook, which lay in a valley just south of Princeton. A rebel working party was breaking down a bridge over a creek. Guns were rushed forward to disperse the rebels, but Cornwallis would consider no delay while the bridge was repaired. He ordered the infantry to wade the icy chest-deep stream while his engineers reconstructed the crossing for the artillery.

At noon the British forward units entered the Princeton outskirts just as the rebel rear guard was leaving on the road to New Brunswick. The dragoons and the light infantry moved on after them to harry them, but there were not enough of them to fight a battle. It was late afternoon by the time Cornwallis’ main column was in the town and formed ready to advance. Anxiously, he pressed on after the rebels along the road to New Brunswick.

But Washington evidently was not aiming for the British regional headquarters, at least not by the main road; he branched north across the Millstone River “into strong country,” as the official British report put it. “Lord Cornwallis, seeing it could not answer any purpose to continue his pursuit, returned to Brunswick.”

Two days later Cornwallis wrote to London that Washington was at Morristown. “He cannot subsist long where he is,” he said optimistically. “I should imagine that he means to repass the Delaware at Alexandria. The season of the year would make it difficult for us to follow him, but the march alone will destroy his army.”

This was a big overstatement. The rebels remained in Jersey, raided Elizabethtown and Hackensack, until Howe decided to maintain winter posts only at New Brunswick and Amboy.

Truly, Trenton and Princeton, though Washington had executed them skillfully, were only skirmishes. The push beyond New Brunswick always had been a bonus, and the military situation was now very little different from what Howe had planned at the end of November.

Their main impact was as a morale booster for the rebels, but to the British in New York, this seemed fairly minimal. ‘The British cause in America,” wrote a correspondent to William Eden in London, “certainly does not depend on the conduct of a Hessian Colonel. . . . I saw yesterday a man from Philadelphia who says this affair highly raised a few and but a few. The generality continue dispirited; they see their Congress fled . . . their armies much dispersed . . . their jails full, masters and families and servants forced into the army. . . . The back of the snake is broken. She can never recover to hurt but may hiss a little before she gets to her hole and dies. . . .”

To Howe, it was a minor setback—for which, with some reason, he completely blamed Colonel Rall—“the only disagreeable occurrence that has happened this campaign.”

Across the Atlantic, however, it did not seem quite as insignificant—especially in the Palace of Versailles.