15

UPPER HUDSON RIVER, August 20, 1777

From the big house where Burgoyne had set up British headquarters some nine miles south of Fort Edward, he could see the Hudson running fast and high, swollen by the storms of the past week.1 The river was central to the critical decision he had to take, especially since the rushing waters had just swept away the bridge of log rafts that his engineers had constructed.

Burgoyne’s triumphant advance had just been badly marred and yet even in retrospect, as he wrote to Germain that day, his bold attempt to solve his problems in one sudden strike seemed fully justified.

Two weeks before, when he was camped at Fort Edward, he realized he must advance fast. The enemy was still smaller in numbers than Burgoyne’s army of professional soldiers, but once St. Leger had reduced Fort Stanwix—only a matter of time, since he was employing the zigzag trench technique to approach and blow up the walls—they would soon be threatened on their flank.

If Burgoyne could attack during the next few days, the rebels would be forced to fight a battle against a superior force or retreat to Albany or New England. But he was frustrated by his lack of land transport and could not order the advance. Worse, “exceeding heavy rains,” as he wrote to Germain, had softened the road from Lake George to the river so that “it was often necessary to employ ten or twelve oxen upon a single bateau.” Even by August twentieth, when his luck had clearly turned, he only had four days’ provisions and ten boats on the Hudson.

Von Riedesel had first suggested raiding rebel sources for supplies when he was camped at Castleton—merely a cautious probe from the main British line—but Burgoyne had rejected the proposal because he was moving his whole army forward. Then halfway through August, tormented by his inability to act, he had planned a far more hazardous move that stemmed from Von Riedesel’s thinking: a strike northeast at the rebel supply dumps at Bennington in South Vermont that would also gather up horses, cattle and wagons. It was dangerous because the detachment would be exposed to attack from the rebel Colonel Warner at Arlington not far to the north and possibly from militia groups from other parts of New England.

Von Riedesel opposed the plan, and Burgoyne, fully aware of the risk decided that the detachment was to be large—nearly 1,000 men, including his ace corps of marksmen that always formed the advance guard for the army, as well as a strong party of Indians. He warned the veteran Hessian Colonel Friedrich Baum, who was to command it, to move his main body with great care “while the light troops felt their way” and to avoid being surrounded and cut off.

On the morning of August 16 Baum’s column had left for Bennington, and the whole army had advanced on both banks of the river to the Batten Kill, a creek that flowed into the Hudson from the hills on Baum’s route, to support the colonel if necessary and to act fast after his return.

Before daylight the next morning Burgoyne had been awakened by a messenger from Baum. The colonel was facing more opposition than he expected. In fact, he was in even greater danger than he realized, for he had allowed what he thought were Loyalists because of the white cockades they wore in their hats to camp on his flanks; but despite their hats, they were rebels—just waiting for the signal to attack him.

Burgoyne ordered out a relief force under the command of another veteran Hessian officer, Colonel Heinrich Breymann, who, so camp rumor had it, was in a state of constant dispute with Baum. This feuding was blamed by some of the British for the slow progress of the relief column, though a more important cause was the teeming rain that created enormous obstacles for the cannon on the steep hill roads.

By the time Breymann reached Bennington he was too late. Except for a few who managed to escape, Baum’s entire force had been killed or captured, and Baum himself was dead. Only by immediate retreat and leaving his guns behind was Breymann able to extricate most of the support corps.

For Burgoyne, who had ridden out personally to meet Breymann and his tired men as they splashed back to camp through the Batten Kill, it was a disaster. He had lost 800 men he could not spare; worse, it had boosted the rebel morale. Baum’s Indians who as usual had been impossible to control had capped the tragic story of Jane McCrea which the rebels had been using to inflame the inhabitants of the New England townships.

As Washington had discovered in New Jersey, the militia was often nervous of supporting a rebel army when the odds were against it. Now Bennington had provided the complete victory it needed for assurance, and as the news spread, they streamed into Schuyler’s camp at Stillwater until they outnumbered the British by a substantial margin.

It shattered Burgoyne’s own men, too. Most of his Indians, many of whom, including the “Grand Chief,” had died at Bennington, decided to leave him. “On their first joining his army,” Lieutenant Digby wrote in his journal, describing the Indian leaders’ explanation to the general, “the sun arose bright and in its full glory; . . . but then that great luminary was surrounded and almost obscured by dark and gloomy clouds. . . .” Many of Burgoyne’s Tories left him too, possibly because those captured at Bennington had been humiliated, killed callously in the act of surrender and, according to one report, branded with a red-hot iron.

Desertions among the regular troops had soared. Burgoyne, who prided himself on his humanity to his men, grasped at the traditional cruel methods to control them. Two men were sentenced to 1,000 lashes, another was executed. The few Indians who remained in camp were used to hunt down any soldiers who were found missing from their tents. In his general orders Burgoyne offered his scouts and sentries “twenty dollars for every deserter they bring in,” directing further that if they “should be killed in the pursuit, their scalps are to be brought off.” It was a drastic policy for a general who had urged his officers not to swear at the men and to treat them as “thinking beings.”

In only a few days Bennington had crystallized all the adverse changes that had been gradually transforming Burgoyne’s situation and forced him to decide the vital question: Should he stay where he was or even drop back nearer Lake George, where his communications and lines of retreat could be sustained, or drive on for Albany?

Albany lay on the west side of the river, and if he went on, he would have to cross the Hudson with his baggage wagons that in a limited way linked him to Lake George and the water route north. Since there would be no troops remaining on the east shore of the river to stop them, “I must expect a large body of the enemy . . . will take post behind me.” He would be cut off from supply communication from Canada, so his army would have to carry all its provisions and ammunition and get through to Albany before the stocks ran out.

Obviously an advance with so many imponderables would be a colossal gamble; the militia, which had been discounted to some extent in the planning of the operation, was now roused and hostile on a big scale. “Wherever the King’s forces point,” he wrote that day to Germain, “militia to the amount of three or four thousand assemble in twenty-four hours.”

Information had now come in that General Horatio Gates, who had taken over the rebel command the day before from Schuyler, was newly equipped with French cannon landed recently at Boston. And Putnam had sent up 2,000 men from the New York highlands; he had been able to do this, Burgoyne pointed out bitterly, because “no operation, My Lord, has yet been undertaken in my favor; the highlands have not been threatened.”

He still did not know if they would be or even if any of his dispatches urging this had reached Howe. Two of his messengers had been intercepted on their way south and hanged, and it was possible the others had been captured, too.

There was no doubt Burgoyne should have stayed on the east bank of the Hudson until he had set up contact with the British in the south. And, as he wrote to Germain, this is what he would have done if there had been any “latitude” in his instructions. As it was, he took the astonishing view that he had no alternative but to advance. “My orders being positive to force a junction with Sir William Howe,” he wrote, “I apprehend I am not at liberty to remain inactive.” Yet, only two weeks before, he had heard from Sir William, and it was the second letter saying this, that he would not be there.

Burgoyne was an operator who had attained his high position through a certain natural cunning, a great deal of charm and a degree of ability. He may have been weak on his attention to detail, such as the organization of his land transport system which was the basic cause of most of his problems, but he was not a complete fool. There can only be one explanation why he took the decision he did on August 20. Appalled at the adverse impact he knew a retreat would make at St. James’s, he had become temporarily unbalanced.2

He was a gambler, of course, and he was now making the wildest play of his life—with thousands of men as the stake.

Having made his desperate decision, Burgoyne delayed only until provisions for twenty-five days could be brought up. To take charge of the transport operation, he had ordered the efficient Von Riedesel back toward Lake George, where the German general had been joined by the Fridericke, the Baroness von Riedesel, his pretty blue-eyed wife, and their three children, one of whom was only eighteen months old. She was one of a number of officers’ wives who had now come up Lake George by boat and before long were to be involved in war almost as closely as their husbands.

On August 28, eight days after Burgoyne had decided to advance, an Indian arrived at his headquarters with yet more bad news. A rebel detachment under Arnold had relieved the rebel garrison of Fort Stanwix without firing a shot. St. Leger’s Indians, discomforted by their lack of blankets, raided during the Oriskany ambush and, scared on by the reported size of Arnold’s corps, forced the British colonel to retreat. Burgoyne had to face the grim fact that not only was there no longer any threat to the rebel flank from the Mohawk, but he would not have St. Leger’s force of nearly 2,000 men he so badly needed.

Even this new development did not change his plan to cross the Hudson. By now, providing further evidence that his mind was strained, his view of himself as a martyr general was beginning to form. “The expedition which I commanded . . . ,” he wrote later, “was evidently intended to be hazarded.” For if he retreated to Canada, it would leave “at liberty such an Army as General Gates’ to operate against Sir William Howe.”

Whitehall was capable of big blunders, but if Burgoyne had been thinking clearly, he could never have believed that even the British administration could have intended deliberately to sacrifice—to “hazard”—an army. No military objective could possibly have justified it, especially since, as Burgoyne well knew, such a decision must have enormous political repercussions in Europe.

On September 13 the British army was ready to move and crossed the Hudson over a bridge of boats.

A few days before, the rebels had moved north from Stillwater—where they had been forced to remain during the threat from the Mohawk and which was open country well suited to the British fighting techniques—to high and wooded ground where the British lines could not form easily, where targets for the cannon could not be seen clearly, where riflemen could find plenty of cover.

Slowly, with drums beating and colors flying, the British army moved south through the gorge-creased hills parallel with the river, while another column, with the boats, the wagons and most of the cannon, proceeded along the flats that bordered the water.

Progress was slow because the rebels had broken down all the bridges across the ravines, but the army did not have far to go. The rebel force was only 10 miles away.

The British waded the Fishkill Creek, just south of Saratoga, passed Philip Schuyler’s great mansion and harvested his wheat, which surprisingly, despite his exhortations to everyone else, he had left undestroyed.

By the seventeenth the British were only four miles to the north of the rebel position on Bemis Heights, their lines stretching from the hills to the river where their main provisions were still in the boats. That morning they heard the rebel drums beating the men to arms.

Bemis Heights was a high plateau that sloped upward to the west from the river. It could be approached only by a steep ascent mostly through thick woods, which concealed it from reconnaissance except at very close quarters. The camp had been thoroughly fortified for siege, almost completely surrounded by long, wide walls of earth and felled trees, and all around were steep hills, crisscrossed with ravines.

The battle was imminent. Although Burgoyne wanted time to prepare the ground for his approach and his engineers were repairing bridges under the protective cover of no fewer than 2,000 men, he knew that the rebels might attack him instead of just waiting for an assault. There was continual skirmishing near the working parties and at the outposts. A foraging team was shot to death digging up potatoes in a field. In his general orders Burgoyne coldly pointed out that the men had no right to put themselves in jeopardy—‘The life of the soldier is the property of the King”—and warned that “the first soldier caught beyond the advance sentries of the army will be instantly hanged.”

For two tense days the army waited. They slept in the open, their tents still loaded on the wagons and in the boats. “We were very watchful,” recorded Lieutenant Digby, “and remained under arms.” They were only too conscious that badly outnumbered though they were and since retreat would now be problematical, they must win the battle or face the prospect of being starved into surrender. Already General Phillips had warned the artillery officers to save as much ammunition as they could and to remonstrate with the commanders they served if they believed their firing orders wasteful.

The morning of the nineteenth, though fine, was cool; fall was near, and a hoar frost whitened the grass. By nine o’clock Burgoyne’s army was advancing to attack the rebels on Bemis Heights in three divisions, which, owing to the woods, were out of sight of one another much of the time. Phillips and Von Riedesel were with the left column moving along the riverside, led by a party of “shabbily mounted” Hessian dragoons, who were covering the baggage in the boats.

Burgoyne himself was with the center, which, under the immediate command of General James Hamilton, was approaching through the hills.

Brigadier General Simon Fraser, in charge of the right wing made up primarily of the advance corps, was moving through the woods in a wide circuit to assault the rebel lines from the west.

The terrain was difficult and, as Burgoyne had realized, several hours were required before the three columns could get across ravines and through woods to their starting positions for the attack. Carefully the center division moved down into the “Great Ravine,” which lay in front of the rebel camp, crossed a bridge over the stream at the bottom and halted around noon. For an hour the troops waited until Burgoyne received a message from Fraser that his column had at last reached the high ground to the west—to the right of the main buildings of Freeman’s Farm, which was his springboard for the assault.

Freeman’s Farm, a cluster of log cabins set in a few acres of open ground axed out of the forest, lay directly between the center column and Bemis Heights, about a mile and a half away. When Burgoyne reached the farm, the British line would be formed as well as it could be in such rough country. Fraser would be in the woods to the west of him. Von Riedesel would be attacking uphill through trees from the river to the east, though the German general seems to have been very unsure of exactly what was expected of him.

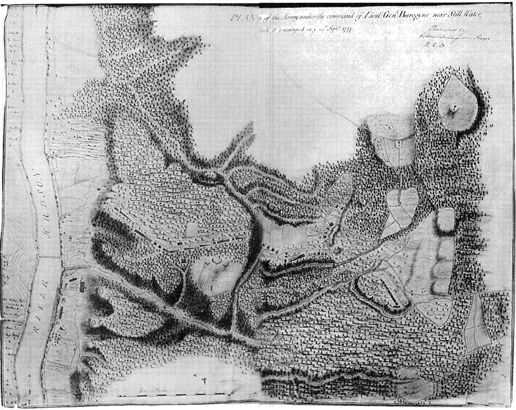

Army positions after the Battle of Freeman’s Farm, on September 20, 1777.

The British Museum. A Royal United Services Institution map.

Soon after one o’clock, Burgoyne ordered the firing of three musket shots, the signal for the advance on the fort, and his column with its cannon began moving slowly up the hill toward the farm.

At daybreak, intelligence had arrived at British headquarters that Daniel Morgans and his celebrated corps of “ Virginian “riflemen, now complemented with men from other provinces, were posted in the woods in front of the rebel camp. Morgan was well known to detest the British; once during service with the army under General Braddock in the French and Indian War, he had punched an officer who had struck him with the flat of his sword. He had been taken prisoner in the assault on Quebec, and Carleton had offered him a colonelcy if he would defect; but indignantly he had refused. He was a highly individual but brilliant natural commander. Instead of using drums to control his men, who were all expert shots, he sounded a decoy call that was designed for luring wild turkeys.

Fraser’s advance troops on the right were the first British units to encounter Morgan’s men. From high branches of the trees where the riflemen were perched came lethally accurate shots—aimed as always at the men who wore braid epaulets. Immediately the pickets fell back to Fraser’s advancing line, “every officer,” according to Lieutenant Digby, “being killed or wounded.”

Fraser sent forward his light infantry and grenadiers, and under the blaze of drilled and coordinated shooting by ranks, Morgan’s men were forced back. “About half past one, the fire seemed to slacken a little,” reported Digby, “but it was only to come on with double force. . . .”

The rebels attacked again, this time supported in strength by troops commanded by Arnold, and the fighting became desperate. “From the situation of the ground and their being perfectly acquainted with it,” wrote Digby, “the whole of our troops could not be brought to engage together . . . such an explosion of fire I never had any idea of before, and the heavy artillery joining in concert like great peals of thunder, assisted by the echoes of the woods, almost deafened us with noise.”

Fraser’s column bore the brunt of the defense at the early stages of the battle, but it was in the center that the key action was soon to be fought.

As the center column approached the farm through the woods on the hill, General Hamilton sent forward an advance unit of 100 men. They, too, met Morgan’s riflemen, for he had posted them strung out in a long irregular line waiting in the log farm buildings, as well as in the trees.

The probing British companies met the same precision shooting that dropped so many men in Fraser’s forward pickets on the right. And again casualties, especially among the officers, were high. Worse still, because of a stretch of open ground, they could not retreat and were pinned to cover.

Fraser, on their right, heard the shooting, realized the situation and ordered his light infantry to rescue them by swinging left and attacking. Under the blast of fire, the rebels fell back, and for a very short while, there was a lull in the fighting.

Hamilton’s advance guard, after having been rescued by Fraser’s light infantry, had dropped back to the main body of the center division. Now the general ordered an advance in strength, halting his men as they came to the edge of the woods that fringed the land surrounding the buildings of Freeman’s Farm. His gunners put a couple of 6-pound shot into the log cabins from which Morgan’s men had attacked his vanguard, but it induced no response; the rebels apparently had vacated the farm and dropped back into the woods beyond.

The infantry rushed across the clearing—under a blast of fire from the trees—and took cover behind the log cabins. As soon as they were stationed, the four cannon were galloped after them, the teams unhitched and the guns set up in pairs on both wings.

In the heavy fighting that Digby recorded, Arnold had been trying to push his troops around Fraser’s right wing so that he could attack him from the rear. Now he had switched his tactics and had withdrawn his men and was now making a drive between Fraser’s right wing and Hamilton’s center to separate them. In response Hamilton regrouped his regiments in the form of a V—a salient—in front of the farm.

For three hours they fought it out, moving backward and forward across the field between the farm and the woods. ‘To an unconcerned spectator,” commented Digby, “it must have had the most awful and glorious appearance, the different battalions moving to relieve each other, some being pressed and almost broke by their [the rebels’] superior numbers.”

Repeatedly the British guns were captured and then recaptured in bayonet charges. The casualties were terrible, especially among the Sixty-second Regiment, which was posted at the point of the British salient and under attack from an arc of fire.

Lieutenant James Hadden, in charge of two guns on a hill at the left of the salient at the farm, had nineteen of his twenty-two men killed or wounded. Unable to fire either of his guns, he rushed to General Hamilton and asked for infantrymen to help him get the cannon back into action, but the general could not spare any men and referred him to General Phillips, who had ridden over from the left wing by the river to find out what was happening.

Immediately Phillips ordered Captain Thomas Jones, Hadden’s brigade commander, to transfer the crew from a gun on the right of the salient to get one of Hadden’s cannon firing again. When Hadden returned to his guns with his new crew, he found the line of the Sixty-second in confusion. Because the cannon had stopped firing, the rebels had stepped up the pressure on this front, and to counter them, the regiment had charged with the bayonet, and the troops had gone too far into the wood. Rebels concealed among the trees closed from the sides and captured twenty-five men from a corps that certainly could not spare them; half the men and more than half the officers had already been killed or wounded.

As soon as they got to the guns, Jones and Hadden opened fire, and immediately Morgan’s snipers in the treetops concentrated on the artillery crews. Almost at once Jones was shot; all the gunners that Hadden had brought up were wounded. Once more his cannon were silent.

The line dropped back on the farm, but Hadden was forced to leave his guns on the hill. He carried his bleeding commander, Captain Jones, “into one of the huts which was filled with wounded” and, only with difficulty, found “a place to lay him in.”

Von Riedesel on the riverbank could hear the fighting but was uncertain how to interpret his orders, for he was responsible for the boats and wagons. He sent an officer to Burgoyne for guidance, and the captain returned with instructions that the general leave a strong party to protect the baggage and to join the battle. Von Riedesel ordered the advance.4

When Hadden returned to the fighting from the hospital hut where he had left his dying brigade commander, the Sixty-second Regiment was still under terrible pressure.

General Phillips, seeing how desperate the situation was becoming, had already sent for some support cannon from the British artillery with Von Riedesel’s column. Then he had galloped off to the left where another regiment, the Twentieth, was posted on the far side of the field. The moment his cannon were rushed toward the advancing rebels and set up, he brought up the infantry, which charged the American flanks behind salvos of grape and forced them back into the woods.

But again the rebels counterattacked. When, with their drums pounding, the Hessians advanced from the river up a steep timbered hill, manhandling their cannon, the British were again dropping back to the farm. The Germans charged through the trees, their guns firing at “pistol shot distance.”

At the same time, Fraser on the right ordered his grenadiers forward in a determined strike. Relieved by this support, with both his wings assaulting the rebel flanks, Hamilton re-formed his shattered center and advanced.

Under this massive three-pronged drive the Americans dropped back to their lines at Bemis Heights. Burgoyne considered an assault on the fortifications; but it was late in the afternoon, and the light was fading. Fighting was becoming impractical. As it was, Fraser’s grenadiers opened fire on the blue-uniformed Hessians, mistaking them for rebels in the dusk. After its mauling, Burgoyne’s army was in no state to storm the stout, high walls of the enemy camp.

The British had held their ground, but already seriously outnumbered, they had suffered nearly 600 casualties, many of whom were still lying wounded in the woods within earshot of the troops who spent the freezing night where they had fought. ‘Though we heard the groans of our wounded and dying at a small distance . . . ,” reported Digby, “[we] could not assist them till morning, not knowing the position of the enemy, and expecting the action would be renewed at daybreak.”

Although the soldiers waited tensely for daylight, there was no action. The morning light revealed the usual heavy mist that marked the beginning of each day. Search parties went out to bury the dead and bring in the wounded who had survived. “Some of them begged they might lie and die,” wrote Anburey, who was in charge of one of the units, “some upon the least movement were put in the most horrid tortures, and all had near a mile to be conveyed to the hospitals.”

Meanwhile, Burgoyne went ahead with plans for an immediate attack on the rebel camp, and the troops were mustered when, according to General Phillips, Fraser urged the commander in chief to postpone the assault until the following day. His light infantry, who were to be the spearhead, were just too exhausted after the long action of the previous day and a sleepless night and needed rest.

Reluctantly, Burgoyne agreed. He used the opportunity to reposition his army so that his line was not so extended, shuffling it left so that his boats and his wagons by the river were better protected. That night, since only half of them were on duty at a time, the soldiers got some sleep. As they changed the watch in the darkness, they could hear the rebels felling trees to strengthen their defenses.

Before daylight a long-awaited messenger slipped into camp from New York with a letter containing only three lines in cipher from Clinton: “You know my poverty [in soldiers]; but if with 2,000 men, which is all I can spare from this important post, I can do anything to facilitate your operations, I will make an attack upon Fort Montgomery, if you will let me know your wishes.”

Montgomery was one of two river forts that provided the nucleus of the rebels’ defense system in the Hudson highlands. Clinton’s proposal was not in the same category as a “junction with Sir William” at Albany, but at that desperate time anything seemed better to Burgoyne than nothing.

“An attack or menace of an attack upon Montgomery must be of great use,” he wrote in reply, “as it will draw away a part of this force and I will follow them close. Do it, my dear friend, directly.”

As soon as it was dark the next night, an officer in disguise left the British camp in an attempt to get through to New York. In case he was captured, as was very likely, the next day two other officers, carrying copies of the same letter, followed him, each taking a different route.

Clinton had only 7,000 troops to defend New York. When Howe had sailed south, he had been alarmed and astonished, mainly because the move left the city exposed to rebel attack. There were in fact two small strikes by rebel detachments, but by September 12, when Clinton sent his small offer of help to Burgoyne, he knew that Howe had landed and Washington was south of the Delaware. Also, he was “in hourly hopes” of the arrival of reinforcements from England.

Clinton’s message decided Burgoyne to postpone his plans to attack the rebel camp. Again it was a gamble. Of the twenty-five days for which the army had brought provisions across the Hudson, only two weeks remained. Possibly with the limited extra produce brought in by the foraging parties and the fewer mouths to feed they could survive a little longer, but the time available for the breakthrough to Albany was getting very short. On the other hand, since Gates’ army was so much bigger than Burgoyne’s, it made sense to wait until he was threatened in the rear.

Instead of mounting an assault, the British entrenched. Massive working parties felled all the trees within 100 yards of their line to give the cannon free play and to strip away all cover. Then they built a long wall of earth and timber behind a deep ditch, and beyond it an abatis of trees, laid side by side, with their branches jutting toward the enemy.

For tense, precious days, they waited—both for news of Clinton’s attack on the highlands and for an assault by the rebels. The two camps were only a mile apart. In each, the men could hear the challenges of the other’s sentries. The British slept in their clothes, their weapons beside them.

On the twenty-first they heard the rebels cheering. In a feu de joie a gun was fired thirteen times, one shot for each of the thirteen rebellious provinces. It puzzled the listening men until a few days later when a Hessian officer, captured at Bennington, was sent over by the rebels with news that Skenesborough had been occupied and Ticonderoga attacked. The fort had held out, but the rebels now controlled the entrance to Lake George and had captured all the British boats.

From the moment Burgoyne had ordered the army across the Hudson, he knew his communications would be severed. But in the taut, tired atmosphere of the British camp, it was unnerving now that it had happened.

Every day and most nights there was shooting at the outposts. “We are now become so habituated to firing,” remarked Anburey, “that the soldiers seem to be indifferent to it, and eat and sleep when it is very near them.”

Then came the wolves. At first, according to Anburey, the British thought the night howling came from dogs. “It was imagined the enemy set it up to deceive us, while they were meditating some attack.” Then the noise was attributed to “dogs belonging to the officers and an order was given for the dogs to be confined within the tents. . . .”

The next night the howling grew louder, and a party was sent out to reconnoiter. They discovered the truth—and the attraction: the lightly buried dead. “They were similar to a pack of hounds, for one setting up a cry, they all joined and, when they approached a corpse, their noise was hideous until they had scratched it up.”

Desertion was a continuing problem. On the twenty-third a man was sentenced to 1,000 lashes. A few days later, because of a mass defection by the civilian Canadians who drove the wagons, Burgoyne ordered all the drivers to be assembled and warned that seven of the deserters had already been scalped and the Indians were still searching for the rest.

By the twenty-seventh no further news had come into camp from Clinton, but Digby recorded a report that a messenger from him had been taken by the rebels with a letter concealed in a silver bullet.5 The man had swallowed it as soon as he was captured, but the plan had not worked. “A severe tartar emetic was given him which brought up the ball.”

The same day a copy of the rebel general orders was being circulated among the British. It did not make encouraging reading. “By the account of the enemy; by their embarrassed circumstances; by the desperate situation of their affairs, it is evident that they must endeavour by one rash stroke to regain all they have lost, that failing, their utter ruin is inevitable.”

It was a fair comment on the British situation which only an imminent attack by Clinton could change. Of Burgoyne’s original twenty-five days, now only nine remained; after that there would be a food crisis. The horses were already dying, for they had now cropped all the grass within the camp and forage was in very short supply.

The next day Burgoyne sent another message to Clinton—this one far more desperate in its wording and containing a significant new feature: a request for Clinton’s orders “as to whether I should attack or retreat to the lakes.” Clinton, as he well knew, had no powers to give him orders—only Howe could do that—but Burgoyne was hoping to shift some of the blame by sharing the responsibility for what, short of a miracle, was clearly going to be a monumental disaster.

By the fourth Burgoyne was facing crisis. Nothing further had come from New York; the troops were now on half rations. That day, for the first time, he called his senior officers to his tent to consider what the army should do. He told them he was planning to leave 800 men to protect the magazines and supplies at the riverside and throw the rest of the army into a strike at the enemy’s left in an attempt to “turn his rear.” Vigorously Von Riedesel opposed the proposal; because of the woods they had been unable to get any reconnaissance parties near enough to assess the targets. They would be attacking blind. Also, the rear guard, protecting the baggage, would be hopelessly vulnerable to rebel attack.

Troubled, Burgoyne postponed a decision for twenty-four hours, and the next day they met again. Von Riedesel urged strongly that they should cross the Hudson and drop back to their earlier camp on the Batten Kill until they heard from Clinton. Fraser supported the German. Burgoyne hated the idea of retreat, but there was no arguing the blunt fact that no one had yet seen the left of the rebel lines, which he had selected as the assault point. He came to a decision: They would reconnoiter in force, foraging at the same time. If there were a weakness in the lines, they would attack at once; if not, he would adopt Von Riedesel’s advice: On October 11, unless there was news of the anticipated attack from the south, he would order the army to retire.

Two days later, at one o’clock in the afternoon, Burgoyne rode out of the camp with all his senior generals at the head of 1,500 of his best fighting troops and ten cannon. They headed southwest in a circuit of the rebel camp and halted after about three-quarters of a mile in an uncut cornfield on a hill. The troops formed in a line 1,000 yards long at the back of the field to cover the foragers as they harvested. From the roof of a log cabin, Burgoyne and his officers trained their eyeglasses on the rebel lines, but the woods blocked their view of the fortifications.

In any case, their problem was shortly to become academic. Shortly after half past two the Americans attacked both British flanks in the woods.

The battle lasted only fifty minutes, but it was a complete disaster for Burgoyne. The British were routed; they abandoned their guns, since most of the horses had been shot, and retreated—“which was pretty regular,” according to Digby, “considering how hard we were pressed by the enemy”—to the lines. General Simon Fraser, spectacular on a gray horse riding up and down the ranks urging on his men, was an obvious target for the riflemen. The first shot went through the crupper behind his saddle; the second sliced his horse’s mane. One of his aides urged him to ride out of the line of fire since a rebel was clearly trying to kill him, but the general refused. There was another puff of smoke. This time the man was on target, and Fraser, shot in the stomach, flopped forward on the saddle. He was the only wounded man the British took with them from the field.

The foragers reached the camp first, galloping back on their horses, having jettisoned their corn—all except one old soldier who came into the lines sitting on the forage, loading and shooting at his pursuers as he rode. “I’d sooner lose my life,” he told an angry officer, “than my poor horses should starve.”

“The troops came pouring back to camp,” reported Anburey, who was in command of a guard. “It is impossible to describe the anxiousness depicted in the countenance of General Burgoyne,” who immediately rode up to the quarter guards. “Sir,” he told Anburey, “you must defend this post to the very last man.”

Almost as he spoke, the guns on the right blasted loudly into action: The rebels were attacking the camp. Again and again the cannon fired, deafening overlapping explosions, spraying metal across the open space that had been cleared in front of the camp. The light infantry, posted on the walls at the point of the assault, were also shooting fast.

The rebels penetrated the abatis of trees—the first line of defense, designed as a check on attackers—only to encounter much too concentrated fire, so they checked and fell back, great holes carved in their line.

Then to the astonishment of the watching British troops,6 a horseman picked his way through the branches of the abatis, probably through a narrow gap left for patrols. They recognized a bulky, black-haired figure astride a brown horse—Arnold, the rebel general.

He leaned forward in his saddle and galloped parallel with the fortifications right across the line of fire. The continual blasts of grapeshot and bullets from hundreds of muskets made it a certain death ride. Every man expected to see the horse crumple under him, but neither Arnold nor his mount were hurt.

He rode on past the end of the main British lines where there were a couple of log cabins and beyond them a redoubt, positioned on high ground to cover the British flank and manned by Colonel Breymann and 200 Hessians. One column of rebels was approaching from the west, where the battle had been fought earlier; Arnold rode up to them, yelled an order to follow him, swung his horse around and rode for the log cabins, which were defended by Canadian irregulars who put up little resistance as the rebels swarmed in.

Urging on the men, Arnold galloped around Colonel Breymann’s redoubt under a continual blaze of shooting and entered through a sally port at the rear.7

The rebel general’s sudden strategy was overwhelmingly successful. The rebels took the redoubt and held off a counterattack. But Arnold’s incredible luck could not last forever. Under a burst of fire at closer range, his horse dropped under him, and he himself was shot in the leg, according to one unofficial report, by a German lying wounded on the ground. “Don’t hurt him,” Arnold is said to have shouted. “He’s a fine fellow. He only did his duty.”

By nightfall the issue was no longer in question. The rebels were in possession of the redoubt, and Colonel Breymann was mortally wounded.

The capture faced Burgoyne with yet another crisis on this disastrous day. For the redoubt overlooked the British lines, making them utterly vulnerable to its artillery; it was vital that he move the army before daybreak.

Ironically, so the British learned later, because of a running feud between the generals, Gates had stripped Arnold of his command and ruled that he should take no part in the action. Burgoyne had been forced to abandon his camp by a man who was disobeying orders.

That night the British evacuated their lines at Freeman’s Farm, went through the ravine they had crossed in their advance on September 19 and camped on the heights of the next hill. “It was done with silence,” Digby recorded, “and fires were kept lighted to cause them not to suspect we had retired from our works.” There was no doubt that the hasty move was necessary; as they marched in column in the darkness, Lieutenant Anburey “heard the enemy bring up their artillery, no doubt, with a view to attack us at daybreak.”

From their new position, they were well placed to fight off the assault they expected during the day and could also protect the hospital tents and supply base that were still where they had been for more than two weeks, in the meadows by the river.

While the British column was moving in the darkness to its new position, Baroness von Riedesel was still awake in the house she had taken over near the river. She had planned to give a dinner party for the generals the previous evening and, although the crisis of the afternoon had canceled it, the table was still laid, “when they brought me upon a litter poor General Fraser (one of my expected guests), mortally wounded. Our dining table . . . was taken away and in its place they fixed up a bed for the general. I sat in a corner of the room trembling . . . the thought that they might bring in my husband in the same manner . . . tormented me incessantly.”

“Do not conceal anything from me. Must I die?” Fraser asked the surgeon, who told him that there was nothing he could do. The ball had passed through his intestines.

“I heard him often amidst his groans, exclaim . . . ‘poor General Burgoyne! My poor wife!’” wrote the baroness. “ . . . I knew no longer which way to turn. The whole entry and other rooms were filled with the sick. . . . Finally, I saw my husband coming . . . and thanked God that he had spared him to me. . . .

“We had been told that we had gained an advantage over the enemy, but the sorrowful and downcast faces which I beheld, bore witness to the contrary and, before my husband again went away, he drew me to one side and told me . . . that I must keep myself in constant readiness for departure.

“I spent the night . . . looking after my children whom I had put to bed. As for myself, I could not go to sleep, as I had General Fraser and all the other gentlemen in my room, and was constantly afraid that my children would wake up and cry and thus disturb the poor dying man, who often sent to beg my pardon for making me so much trouble.

“About three o’clock in the morning, they toldjne he could not last much longer. . . . I accordingly wrapped up the children in the bed coverings and went with them into the entry [of the house].”

Fraser died in the morning at eight o’clock, when from his post in a gun battery in the new British position on a hill Lieutenant Digby was watching “the enemy marching from their camp in great numbers, blackening the fields with their dark clothing. By the height of the work and by the help of our glasses, we could distinguish them quite plain. They brought up some cannon and attempted to throw up a work for them, but our guns soon demolished what they had executed.”

Burgoyne’s plan was to hold off the rebels with his cannon until darkness, when he would attempt a retreat across the Hudson. Later he wrote of hoping to bring them to battle near the river where the open ground would suit his soldiers, but this was ultra-optimistic, for their morale was suffering badly.

Time had almost run out for him. The troops were on very limited rations, and there was only enough food even at this reduced level for a very few days.

Already the rebels were acting to cut off a British escape to the north. Their troops were moving up the far bank of the river, presumably to take possession of the heights at Fort Edward.

At one period during the morning the rebels formed as though they were going to attack. “Several brigades,” recalled Anburey, “drew up in line of battle, with artillery and began to cannonade us.”

In response a howitzer fired, and the high-angled shell fell short. The rebels cheered. “The next time the howitzer was so elevated that the shell fell into the very center of a large column and immediately burst, which so dismayed them that they fled off into the woods.”

Although they did not form again, their guns kept firing. At midday they opened up on the hospital tents, “taking them,” so Digby presumed, “for the general’s quarters.” Orders were given for the wounded to be moved out of range—“a most shocking scene—some poor wretches dying in the attempt, being so very severely wounded.”

Had Burgoyne’s men only known that during those desperate hours in which they moved the hospital tents under shell fire British troops were already in Fort Montgomery, their morale would have soared. Certainly the general might have changed his plan to retreat.

That morning in Fort Montgomery—from which he could survey the Hudson below—Sir Henry Clinton considered with some satisfaction the results of his assault. It had achieved far more than he had hoped originally. Although he had used more men than he had intended, he now controlled the highlands. He had stormed the two major forts and occupied minor positions. He had broken the boom the rebels had constructed across the river and burned all their vessels. “Nous y void,” he wrote to Burgoyne in a note that never reached him, “and nothing now between us and Gates.”

He did not press on immediately to Albany, as Burgoyne had asked, but since he had now been offered reinforcements from Rhode Island, such a plan was forming in his mind.

At sunset Fraser was buried on the hill by the gun battery where Digby was posted, a spot he had specially requested. He had asked for no “parade” other than “the soldiers of his own corps.”

The procession carrying the corpse went up the steep slope in full view of both armies, and as it passed Generals Burgoyne, Phillips and Von Riedesel, “they were struck at the plain simplicity of the parade, being only attended by the officers of the suite . . . and joined the procession.”

The rebels, seeing the gathering of men by the gun battery, opened fire as the funeral service was conducted by the chaplain. “The incessant cannonade during the solemnity,” Burgoyne wrote later, “the steady attitude and unaltered voice with which the chaplain officiated, though frequently covered with dust which the shots threw up on all sides of him; the mute and expressive mixture of sensibility and indignation upon every countenance; these objects will remain to the last of life upon the mind of every man who was present.”

The Baroness von Riedesel was watching from a distance. “Many cannon balls also flew not far from me, but I had eyes fixed upon the hill, where I distinctly saw my husband in the midst of the enemy’s fire.”

“Suddenly the irregular firing ceased,” wrote Benson Lossing, the historian. The rebels had at last realized the reason for the gathering. “The solemn voice of a single cannon, at measured intervals, boomed along the valley. . . . It was a minute-gun fired by the Americans in honor of the gallant dead.”8

The funeral and the dying light of dusk were all that had delayed the retreat. “The horses,” recalled the baroness, “were already harnessed to our calashes.” As on the previous night, the march was to be as quiet as possible. “Fires had been kindled in every direction; and many tents left standing to make the enemy believe that the camp was still there.” It was impossible to move the wounded, so Burgoyne planned to leave them under a flag of truce with a letter to Gates, requesting his mercy.

At nine o’clock the column started moving off in the darkness. Von Riedesel had taken over command of the advance troops, now that Fraser was dead. In her calash, just ahead of the quietly moving column, the baroness tried to keep her children quiet. “Little Frederica was afraid and would often begin to cry. I was, therefore, obliged to hold a pocket handkerchief over her mouth, lest our whereabouts should be discovered.”

Anburey was with the rear guard, which did not leave the camp until eleven. “For near an hour,” he wrote, “we every moment expected to be attacked, for the enemy had formed on the same spot as in the morning; we could discern this by the lanterns that the officers had in their hands and their riding about in front of their line, but though the Americans put their army in motion, they did not pursue us. . . .” Before dawn Burgoyne sent forward an order for the army to halt to allow the provision boats to catch up; meager rations were distributed and the men encouraged to rest.

By the afternoon, when the British continued their retreat, it was raining heavily, turning the roads into thick mud. The baggage wagons bogged down, and Burgoyne gave instructions for them to be abandoned, along with the tents for the weary soldiers.

Not until after dark on the evening of the ninth did the head of the column wade across the ford of the Fishkill Creek, which flowed into the Hudson from the west. Just behind it were the heights of Saratoga and the fortifications that the army had constructed when they had camped there in September. Since he had not yet been able to push his men across the river because the rebels were posted in strength on the opposite bank, Burgoyne had decided to reoccupy his old camp; it was a good defense position, high up and overlooking open ground which would give good scope to his guns.

Burgoyne and his staff officers spent the night in Philip Schuyler’s mansion by the Fishkill and evidently helped themselves to his cellar, much to the disgust of the Baroness von Riedesel, who indignantly described how the house “rang with singing, laughter and the jingling of glasses. There Burgoyne was sitting with some merry companions at a dainty supper while the Champagne was flowing. Near him sat . . . his mistress.”

The general did not escape reality long. At daylight, with the rear end of the column still passing through the Fishkill, Burgoyne withdrew to the camp on the heights and, since Schuyler’s house would provide cover for the rebels, gave orders for the artillery to destroy it.

Gates’ army came in sight in the late afternoon and set up their line just the other side of the Fishkill. There was another strong force across the Hudson, as well as Morgan and his riflemen who had taken a wide circuit and were now posted to the west. Only the road immediately to the north along the west bank of the Hudson was still open.

Early the next day, under the cover of a morning mist, the rebels tried to block this escape route. A large force crossed the Fishkill and struck north along the river road; but the fog lifted, and the British cannon were able to check them.

Again Burgoyne held a council with his senior generals to decide what to do. And again Von Riedesel had a plan. They should abandon their baggage and strike north in darkness, on the chance that they could drive across the river at a ford four miles above Fort Edward. From there the road led to Fort George at the tip of the lake. Since their boats had now been captured, their position would be better by only a margin, but at least they would not be surrounded as they were now.

As he had before, Burgoyne postponed a decision for twenty-four hours, then, the following afternoon, gave his approval; the army would march that night. At ten o’clock, Von Riedesel who was commanding the vanguard sent a message to his commander in chief that he was ready to start. But by then a scout had brought intelligence that “the enemy’s position on the right was such . . that it would be impossible to move without being immediately discovered.” Burgoyne canceled the breakout attempt.

By the following day, the twelfth, it was no longer practical; in the night a big rebel detachment had crossed the Hudson from the east and set up batteries.

The British were now completely surrounded and under constant fire. “Every hour,” recorded Von Riedesel, “the position of the army grew more critical. . . . There was no place of safety for the baggage and the ground was covered with dead horses that had either been killed by the enemy’s bullets or by exhaustion, as there had been no forage for several days. . . . Even for the wounded, no spot could be found which afforded them a safe shelter—not even, indeed, for so long a time as might suffice for a surgeon to bind up their ghastly wounds. The whole camp was now a scene of constant fighting. No soldier could lay down his arms day or night, except to exchange his gun for the spade when new entrenchments were thrown up.”

The baroness and the children had taken over the cellar of a house which she shared with some wounded officers, one of whom found he could stop Frederica from crying by imitating the bellowing of a calf. In the room above their heads, the surgeons were operating under exceptionally difficult conditions; during the course of just one day, Madame von Riedesel reported, eleven cannonballs went through the house. One man, whose leg was about to be amputated, had the other taken off by a shot.

By morning the cellar always stank, and the baroness would fumigate it by pouring vinegar over hot coals. Water, however, was the main problem, for whenever any of Burgoyne’s men approached the river, the rebels opened fire. The shortage was even more acute in the baroness’ shot-battered house because of the needs of the wounded. At last, one of the soldier’s wives offered to take the buckets down to the water, insisting the rebels would not kill a woman. With great courage, she walked to the river, but she was right—they did not open fire on her.

Repeatedly the general begged his wife to allow him to send her and the children over to the Americans. Already one wife whose husband had been taken prisoner had gone to them and been treated with great courtesy by Gates. But the baroness would not hear of it. She had made her own arrangements for the children. Each of three wounded officers in the cellar had agreed to take one child on his horse.

By October twelfth the position of the British was clearly hopeless. No news had reached the camp of an attack by Clinton. Burgoyne held a meeting—not just with his generals but with all his senior officers—and for the first time he mentioned the dread word “capitulation,” which “he had reason to believe had been in the contemplation of some, perhaps of all, who knew the real situation of things.”

He put two questions: Was an army of 3,500 men, “well provided with artillery,” ever justified in surrender? If so, did their present circumstances provide sufficient reason?

The answer to both questions was a unanimous yes, though it might not have been had they known that at that very moment a fleet was sailing up the Hudson through the highlands toward them. It was carrying only 2,000 troops, but Major General Vaughan, its commander, had orders to “feel his way to Burgoyne . . . and even join him if required.”

But Burgoyne, still starved of any information from the south, at last took the inevitable decision and sent a message to Gates under a flag of truce suggesting a meeting between staff officers “to negotiate matters of high importance to both armies.”

The following morning Major Robert Kingston left the British lines on the heights, was met by the rebel Colonel James Wilkinson, who blindfolded him and led him to the tent of General Gates.

The blindfold was removed, and Kingston, as Wilkinson recorded, took the outstretched hand of the rebel commander. Burgoyne, Kingston told him, realized that because of the “superiority of your numbers,” Gates could “render his retreat a scene of carnage on both sides.” He was “impelled by humanity . . . to spare the lives of brave men upon honourable terms.”

“To my utter astonishment,” wrote Wilkinson later, since it was normal for the defeated side to make proposals, “General Gates put his hand to his side pocket, pulled out a paper, and presented it to Kingston, observing: ‘There, Sir, are the terms on which General Burgoyne must surrender.’”

The demand was in effect for unconditional surrender, and when Kingston took it back to his commander, Burgoyne rejected it, insisting that unless some of its terms were altered, “this army . . . will rush on the enemy determined to take no quarter.”

Meanwhile, by agreement during the negotiations, hostilities had been suspended, and the guns were silent. “We walked out of our lines into the plain by the river,” remarked Digby.

Burgoyne proposed his own terms to Gates, insisting that the troops should march out of their camp with the full honors of war, retain their baggage and, instead of being imprisoned, be permitted to return to Britain on condition that they did not serve in North America again during the present contest.

These were arrogant demands for a defeated army to make, but to Burgoyne’s surprise and growing suspicion, Gates agreed to them. His messenger who arrived early in the morning brought only one condition: The formal surrender should take place at two o’clock that day.

There were already rumors that Clinton was approaching. The Baroness von Riedesel even quotes a deserter as coming through the lines with news that the British with a fleet had reached Esopus, 45 miles south of Albany, on October 8—though it is hard to believe that anyone would have deserted to the British during those critical hours.

But it provided Burgoyne with a flicker of hope, and immediately he began to play for time. He asked for the surrender ceremony to be postponed and sent over a request for the word “capitulation” in the document to be changed to “convention.” He sought permission, which was refused, for a staff officer to view the rebel troops to assure himself that Gates’ army truly was three to four times the size of his own, which he suggested somewhat speciously, was the reason for the surrender.

For Burgoyne the timing was tragically narrow. The strange deserter, quoted by the baroness, was right on all his facts—except the date. Only on that afternoon while the general’s negotiating officers were arguing points with their rebel opposites were the British ships off Esopus slowly working upstream against an adverse wind.

There were signs of an active defense. Although the British were still out of range, the rebels were manning batteries. Major General Vaughan landed the troops and set the town on fire. It was there that he was told that a messenger had arrived the previous night with the news that Burgoyne had surrendered. This was enough for the general. His soldiers went back aboard the ships and the fleet headed back to New York.

At Saratoga, Burgoyne was still doing what he could to drag out the negotiations. He even consulted his officers on whether he could honorably withdraw from the agreement his negotiators had signed but still awaited his ratification. There was disagreement on this, but Von Riedesel was adamant that, honor apart, it would be utterly foolish to risk such excellent surrender terms for an unconfirmed report that could be wrong.

Gates ended the dithering. He sent a blunt note to the British camp: Unless Burgoyne signed the agreement within two hours, he would reopen hostilities. Reluctantly Burgoyne signed.

At ten o’clock the following morning, with its bands playing, the army marched from its lines on Saratoga Heights. “But the drums have lost their former inspiriting sounds,” commented Digby glumly, “and, though we beat the Grenadiers March, which not long before was so animating, yet then it seemed by its last feeble effort as if almost ashamed to be heard on such an occasion.”

Across the Fishkill, in the American camp, another band was playing “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” the song that had been transformed from a British taunt to a rousing rebel anthem.

It was the only action that was in the least provocative. Gates had done his utmost to reduce the humiliation of the surrender. He had ordered those troops who had crossed the Fishkill to return within their lines, so that as the British piled their arms in the riverside meadow, they did not do so under the gaze of the enemy that had defeated them.

Burgoyne’s soldiers were impressed, too, as they marched on through the rebel camp by the demeanor of Gates’ men. “I must say,” said Digby, “their decent behaviour during the time (to us so greatly fallen) merited the utmost approbation and praise.”

“Not one of them was properly uniformed,” remarked a Hessian officer, “but they stood like soldiers, erect with a military bearing. . . . There was not a man among them who showed the slightest sign of mockery. . . . It seemed rather as if they wished to do us honor.”

Burgoyne and his general had gone across the Fishkill earlier to dine with Gates. The meal had been surprisingly cordial. The British commander had proposed the toast of George Washington, and the American general had responded by raising his glass to King George III.

It is not entirely strange that later, when Burgoyne tried to comfort the Baroness von Riedesel with the words “You may now dismiss all your apprehensions, for your sufferings are at an end,” she responded acidly: “I would certainly be acting very wrongly to have any more anxiety when our chief has none—especially when I see him on such a friendly footing with General Gates.”

By then the surrender ceremony had been completed. The British troops had been halted near Gates’ large tent, and as the two commanders emerged from it, the American general “paid Burgoyne almost as much respect as if he was the conqueror,” recorded Digby. “Indeed his noble air, though prisoner, seemed to command attention.”

The two men faced each other. Burgoyne drew his sword and handed it to Gates, who received it with a bow and returned it, and the northern army began its long march on the road to Boston.

In Philadelphia, five days later, Howe heard reports of the surrender and wrote Germain his opinion that they were “totally false.” The success of his own army was by no means complete. Earlier in the month the rebels had attacked his camp at Germantown, the site of the main British encampment, and although he had driven them off, the move was clear evidence that Washington was not beaten yet.

Meanwhile, the Delaware was not open to the British fleet. The garrisons of rebel forts on the islands downriver had not surrendered. Only the day before Howe wrote to Germain, a Hessian attack on one of them had been driven off with enormous casualties, and two British ships had been set on fire.

It took Howe more than a month to take the islands. Although it was getting late in the season for campaigning, on December 4 he made one last attempt to destroy the rebel army with a sudden attack on its camp in the hills at White Marsh, but Washington had chosen his position too well. There were actions, and one of Howe’s copybook flanking movements, and the Americans even retreated at one stage; but at last it became clear to the British general that success, even if he achieved it, would be costly. He withdrew his army and returned to Philadelphia for the winter.

The Continental Army, as always at the end of the year, was ragged and ill equipped. This time it was short of food as well. Washington led it to the barren hillside of Valley Forge on the west bank of the Schuylkill to spend the cold bleak months until the spring.

But then it would no longer be fighting the same kind of conflict. Burgoyne’s surrender was to cause a drastic change in the character of the Revolution and the attempts to subdue it. Until then the battles had been events in what was essentially a domestic affair within the British Empire. Now the revolt of the American colonies against their king was to become a world war.

Two days before the British army marched from Philadelphia on its way to the hills at White Marsh, the first report of Saratoga reached Europe.