17

ALLENTOWN, NEW JERSEY, June 25, 1778

It was still dark when the advance guard marched, but already the dawn air was warm, warning of yet another sweltering summer day with temperatures up in the nineties.1 For the first time, the position of the column of the baggage train, 12 miles of wagons and cattle and women, had been changed. Until this morning, while the army had been moving north, it had been kept at the rear; but now that the troops had swung east and the main point of danger had changed, most of the men were waiting at the roadside as the creaking carts lumbered past, with the women walking beside them.

The women had caused Clinton a good deal of trouble. Always the source of problems to commanders, these were immeasurably increased in a retreat when they could not be left in a rear base. When he had first planned the evacuation, Clinton had decreed that only two women per company could accompany the army—provided they were “known to be good marchers, as no carriages will be allowed for them or their baggage.” The others would go by ship. Repeatedly he changed their position in the column and tightened the supervision of them. They were not keen on traveling by sea—probably because the scope for plundering was so limited—for five days after the army had started marching, Clinton complained in his daily orders that, “many [women] . . . who had been sent on board the transports at Philadelphia were at present with the army.”

Clinton’s decision to take this long and motley column to New York by land involved enormous risk—but a risk only marginally smaller than alternative ways of evacuating the city. Before the British left Philadelphia, the main rebel army with about 14,000 combat troops was still at Valley Forge, only 25 miles away to the northwest. Gates with another 4,000 men was on the Hudson. If the militia was rallied, the British could find themselves as outnumbered as Burgoyne had been; moreover, no matter what route Clinton took to reach New York, his enormous column would have to pass through “several strong defiles” in New Jersey’s hills, where he would be dangerously exposed to attack.

Clinton’s emotions were mixed, as his notes and writings make clear. His overriding purpose, as he put it, was “unquestionably retreat,” but after the humiliation of Saratoga he was yearning for a battle. If he could only tempt Washington to attack him—and could then defeat him—the personal reward for him as the commander in chief would be enormous. In national terms, it could well make France think again and act as a curb on Spain.

Given the opportunity, his chances of a victory were higher than they seemed. After three years’ campaigning, Clinton’s army was probably the finest in the world. “I had little doubt respecting the issue of a general and decisive action with them.”

On the other hand, in addition to his superior numbers, the initiative was with Washington. He could choose his battleground—and New Jersey with its craggy hills and woods seemed ideal—and he could march light, without the encumbrance of a vast baggage train.

But, Clinton pondered, why should Washington risk any kind of confrontation? The Peace Commission had now arrived from England and had sent a message to Congress indicating they were keen to negotiate and, as the rebels knew, empowered to be generous. Freedom from taxes, representation in Parliament, removal of the British army and many other of the factors that had caused the rebellion were now to be offered to the Americans.

Congress, however, refused adamantly to discuss anything until its independence had been acknowledged or until all British soldiers had left American soil—leaving the negotiators waiting with nothing to do until they received further instructions from London.

Certainly the evacuation of Philadelphia did not strengthen their negotiating position. Nor did it give Washington any incentive to expose his men to danger. But there were other considerations. Clinton’s vulnerable column was certain to be an attractive target for the rebel commander—especially its baggage train badly needed by his underequipped army that had endured a very hard winter at Valley Forge. Also, another victory over the British would be important politically to the Americans in their new relationship with France.

For these reasons, Clinton prepared to withdraw the army from Philadelphia in an atmosphere of dangerous uncertainty. Would Washington attack? Would he try to grab the British baggage train? And if he were going to attack, would he strike at the very beginning of the evacuation when the British were most vulnerable, as the army was crossing the Delaware?

The rebels made no challenge at this stage. All day on June 17, under the cover of the guns of the warships, the baggage was pushed across the water to a well-defended bridgehead that had been set up on the Jersey bank. That night in darkness, the main body of the troops followed it in flatboats. Then the big transports, with the rest of the baggage, a regiment of Hessians whom Clinton did not trust and the Tory wives and daughters, dropped downriver to Delaware Bay to be ready for the quick dash in convoy for New York.

As soon as the river crossing was complete, the army began marching, leaving Philadelphia open to the rebels.

The British met little in the way of opposition to start with. There were obstacles: The bridges were all down, trees had been felled here and there to block the road; but there was no real challenge.

Clinton left the baggage train at Haddonfield, only seven miles from the river, while the engineers cleared the road ahead. Also, he expected trouble in the pass through the hills at Mount Holly, and had prepared a flanking plan to meet it. He wanted to clear the heights before he brought up his hundreds of wagons.

Strangely, the pass was not contested. Rebel militia were posted there, but they retreated as the British advance corps approached and on June 21 Clinton sent orders back to Von Knyphausen, who commanded the troops in charge of the baggage, to join him.

Even though the march had been relatively easy so far, Clinton was now fairly certain that Washington was going to challenge him. For two days, his agents reported, the rebel army from Valley Forge had been crossing the Delaware at Coryell’s Ferry some 50 miles to the north. Its headquarters had been set up at Hopewell not far from Princeton, but forward units were probing south. Also, Gates was reported to be on the march toward them from the Hudson.

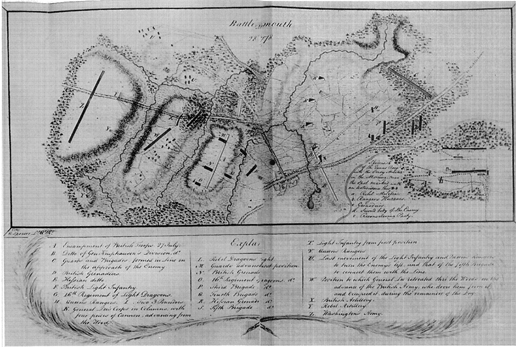

The Battle of Monmouth, June 28, 1778.

Journal of Operations of the Queen’s Rangers by John Simcoe, 1787.

Slowly the British army with its wagon train proceeded north toward the rebel forces that so substantially outnumbered it. Another column, commanded by Cornwallis, was advancing cautiously along a road farther west, nearer the river, to provide cover against sudden attack.

The weather had been changing drastically—torrential rains interspersed with spells of intense and overwhelming sunshine—but by Wednesday the twenty-fourth, the storms had stopped. The soldiers marched under a fierce sun through thick hot sand on the road that glared the heat back at them.

The skirmishes had grown more serious, too. Several times Lieutenant Colonel John Simcoe, with the huzzars of his Loyalist Queen’s Rangers in their green uniforms, had charged sniping parties, and the noise of light guns employed to clear small groups of rebels from the cover of trees and houses had been heard all day along the column.

That day they reached Allentown. Until then, while marching north along the line of the Delaware, Clinton had been able to keep his options open regarding his exact route to New York. Now, he had to decide how he was going to cross New Jersey—and to reveal it to Washington. He could aim straight north for the Hudson or northeast for Staten Island at the mouth of the Raritan or, as he now planned, swing farther east still and make for Sandy Hook, where the fleet could pick him up and ferry the army through the Narrows to New York. This road, via Freehold and Middleton in Jersey’s Monmouth County, ran through country that was fairly open, and Clinton hoped that Washington “might possibly be induced to commit himself some distance from the strong [hilly] grounds of Princeton, along which he had hitherto marched.” And to his surprise he was right, for he found that the terrain was not favorable to the rebels.

At 4 a.m. the next morning, the twenty-fifth, when the British wheeled to the east, the baggage train took the lead behind the advance corps. The new route, with the wagons at the front, eased some of Clinton’s anxieties. Until that morning he had been marching toward the enemy; now with the change of direction, the rebel army was behind him. As a result, the closer his baggage moved to the coast, the easier it would be to protect. His strong rear guard, consisting of the “elite” of his troops commanded by Cornwallis, had a freedom of movement for aggressive action that it had lacked before because of the need to protect the long line of carts.

The column progressed slowly toward Freehold as the sun burned down from a cloudless sky; by midday the temperatures had passed the hundred mark. Swarms of mosquitoes raided the streaming skins of the thousands of sweating men and women. Soldiers fainted; some even died.

The rebels were getting close now. Minor attacks were in motion all day, and it was rumored in the column that among their assailants was Morgan and his riflemen, who had been so effective against Burgoyne’s troops in the woods at Freeman’s Farm.

Often Cornwallis kept his cavalry hidden in the woods at the rear of the column in the hope of cutting off attackers, but he was never able to bring them into action.

That night the advance corps halted about four miles from Freehold. The next morning they entered the village, and Clinton decided to “halt there for a day and look about me.” The general had good strategical reasons for a pause, for he was exceptionally well positioned. Freehold, a little cluster of some forty clapboard houses ranged around the steepled, slate-roofed Monmouth County Courthouse, was at a right-angled junction of the main route from Allentown, along which the British had approached, and the road from Cranbury, where Clinton’s scouts had located the “gross” of the rebel army.

It was Clinton’s last chance of an action, and the dangers that faced him were fewer now than at any time since he had evacuated Philadelphia. The safety of the high ground at Middletown, which adjoined the coast at Sandy Hook, was only 12 miles away. Freehold itself, where his tents were now pitched, was a very strong defense position set on a high ridge of hills with woods all around it.

However, when Clinton and his escort rode up the Cranbury road, which the rebels would presumably advance along, his hopes of “a decisive action” faded. For in the last mile to Freehold, the route cut through country crisscrossed by ravines and surrounded by marsh and woodland. The road itself crossed three of these ravines before reaching Freehold. Clinton could not believe that Washington would risk pushing his advance troops through the first ravine because the restrictions of the terrain would keep him from rushing support if the British attacked in force. Equally, any forward movement would be limited in those defiles with fast retreat impossible.

So Clinton rode back to his headquarters in the Monmouth Courthouse convinced that, since he “could not entertain so bad an opinion of Mr. Washington’s military abilities” as to think he would take either risk, there would be no major battle here. But on the march to Middletown, his baggage train would still be highly vulnerable to serious raiding, especially when the road reached downhill from Freehold between high ridges, and he knew the rebels were considering an attack at this point because all day on Saturday, the twenty-seventh, the British had clashed with their reconnaissance parties examining the ground.

At dawn on Sunday morning Von Knyphausen and his hundreds of wagons started off down the steep hill road toward Middletown. Clinton wanted to move the column past those dangerous ridges as early as possible, but because he knew the rebel “gross” was now at Englishtown, only five miles away along the Cranbury road, and he could not be certain of Washington’s intentions, he held back Cornwallis and the rear guard at Freehold under orders not to march until several hours after the wagons were on the move.

Meanwhile, his mounted scouting troops were on the alert around the village for any signs of enemy activity. The rebels were there all right—and in some force. While the main body of the army was marching out of the village at eight o’clock in the heat of an already scorching sun, Lieutenant Colonel Simcoe with forty huzzars of the Loyalist Queen’s Rangers clashed with a large group of the enemy in the woods to the northeast of the courthouse.

The enemy movement was puzzling to Cornwallis, who did not order the rear guard to move off from the village until ten o’clock. By then they were gathering in some force on the edge of woods across open ground on a hill overlooking the Middletown road. Uncertain of their purpose, the general ordered measures to keep them at their distance. Guns were unlimbered at the rear of the column and opened fire. “A few cannon shot,” recorded John André, “put the infantry back in the wood. Only the cavalry continued to follow.”

Then, a few minutes later, a large rebel column appeared far back on the Cranbury road, and wheeled to join the other troops high up in the open ground. Now in their new strength, the rebels began to advance, following the marching British troops under the cover of their guns. Cannon shot began dropping into the rear of Cornwallis’ column.

Clinton was riding some distance ahead in the column as it moved down the hill when the reports of the enemy’s actions began to reach him. Aides from Von Knyphausen had ridden back to warn him that the rebels were attacking on both flanks of the baggage train. Also, another big detachment had been sighted approaching from the north.

By now Clinton had heard the cannon fire from the rear, and a staff officer galloped up from Cornwallis with the news that the enemy had begun “to appear in force on the heights of Freehold that he had just quitted.” Clinton turned his horse and hurried back to the rear. He was delighted, and surprised, by the new events because it meant that Washington had taken the decision he had been certain he would avoid. He had pushed his advance guard across the ravines and, in doing so, had severed it effectively from the main part of his army.

Now it seemed Clinton might get the battle he hankered for under conditions that were exceptionally favorable.

For the road was leveling out onto a “small plain” nearly three miles long. He had open country, an enemy that was limited in numbers—they were about 4,000—and the barrier of the defiles to prevent Washington sending up support on any scale. In addition, by attacking, he could relieve the pressure on his baggage train. He planned to strike so hard that General Lee, who was in command of the rebel vanguard, would have “to call back his detachments from my flanks to its assistance.”

It happened just like that and much more easily than Clinton expected. While his long line of wagons continued slowly toward the heights of Middletown, 2,000 men in the British rear guard, supported by 4,000 other troops in the column, turned about and started marching back toward Freehold.

Seeing the danger of the open country, the rebels dropped back onto the hill that overlooked the Middletown road and formed in front of the wood. The enemy cavalry, commanded by the young Marquis de Lafayette, advanced from the rebel right wing as though to attack, but the experienced Clinton could see that he was not too sure of his tactics, “seeming to be in the air.”

He ordered the dragoons to attack. But as the cavalry with sabers pointed galloped at the rebel horsemen, “they did not wait the shock, but fell back in confusion upon their own infantry.” The British trumpets sounded the retreat, and the dragoons reined in their horses.

This precipitate withdrawal evidently shook rebel morale. When the thousands of British infantry formed and with drums beating, advanced in line, they retreated. “Nor was a shot fired,” sneered André, “until we had crossed the Cranbury Road.”

Unlike some of his officers, Clinton believed that this was the only action open to Lee. He felt that the whole rebel movement, which exposed the vanguard, was a grave tactical mistake—one which he was now planning to exploit. Washington, however, it was learned afterward, was so angered by the retreat that he assumed personal command of the troops and a few days later ordered his general’s court-martial for disobeying orders.2

As the British line moved forward steadily, leaving the Monmouth Courthouse and Freehold Village on its left, the rebels streamed back along the Cranbury road; since it was too narrowtoprovide an escape route for the entire force, they fanned out to the south through woods that bordered the road. Still roughly formed, they slithered down the steep sides of the first and most easterly of the three ravines they would have to get throughtoreach the main body of the army.

Clinton had foreseen the rebels’ inevitable dilemma once they started retreating. Although the rebels could scramble through the first two ravines, he knew that they could not easily cross the third defile because it was far deeper, with high, steep sides; they would have to cross it the same way they had advanced that morning—by the road, over a bridge. And because of their numbers, that would take time. Temporarily they would be trapped against the big gorge.

Clinton was grimly confident. If he was careful he might even turn the action into a rout.

He watched the long red ranks of his elite corps, the guards and the grenadiers, sweep across the Cranbury road and check before the first ravine. And on their left was his cavalry, the Sixteenth Light Dragoons; approaching behind, in line like the British, were the blue-uniformed Hessians, their bands throbbing out the step. Already they had their orders: They were to hold the heights by the first ravine, so that the attacking troops could drop back to their protection should this prove necessary.

Meanwhile, the light infantry were advancing in a different direction. Hidden by the woods, they were moving up the northerly route toward Amboy, which formed a junction with the Cranbury road; when they broke from cover, they would be able to fall suddenly on the rebel left flank.

The drums were beating as the lines of sweating men advanced to the first ravine and clambered down the incline. The dragoons pressed their horses, which sank to their hocks in the swamp on each side of the stream.

Their passing of this ravine was not contested; by the time they were across it and the line was formed again and moving forward on the other side most of the rebels were through the second ravine. But by now, even though they were still in full retreat, some guns had been set up.

As the guards and the grenadiers slithered down the sides of the second ravine the white flashes of the cannon marked the new position of the battery. The explosions, deafening in the confines of the gorge, numbed the ears of the soldiers as they wallowed through the marshy bottom. Grapeshot rained on them. Leaving their dead and wounded in the mud for the surgeons, they clambered up the far side of the gorge.

Now that they were across the two obstacles of the ravines, Clinton ordered the classic technique for promoting panic in retreating men. The dragoons with sabers swinging rode down the rebel infantry as the retreating men desperately tried to escape the slashing of sharp steel.

Avid for success, Clinton saw in the situation all the early signs of the rout he wanted so badly. But his cavalry were suddenly checked, completely halted and forced back by a unit ranged behind a fence that would have formed an absolute barrier to a charge. The rebels were “throwing in upon us a very heavy fire through their own troops”; the shooting “galled” the dragoons “so much as to oblige us,” as Clinton put it, “to retreat with precipitation upon our infantry.”

Meanwhile, the American retreat was suddenly slowed by the personal intervention, so Clinton later discovered, of Washington himself. Some of the American troops turned off the road and formed on hills on both sides with their backs to the ravine.

Like the artillery that had raked the British as they had crossed the middle gorge, it was obviously a holding operation—a hurried move to stem pursuit to the bridge and cover an orderly retreat across the ravine. Also, it enabled Washington to set up a drop-back line in strength on the other side of this gorge, using both the retreating troops and reinforcements he was bringing up from the main army.

The British formed for attack in two long ranks to the left of the road. Guns were brought up to cover the assault. The heat was now appalling. Even in the shade the temperature was as high as 96; but most of the combat was fought in the fierce glare of the sun.

Along the whole front the British advanced, their cannon firing. The cavalry, now repositioned on the right, were closely formed, the width of a horse between each man, walking at first to keep pace with the infantry, who were moving forward with their muskets at the hip, bayonets pointed forward, drums beating. The rebel guns, set up on a hill on the left, were firing, too. Men dropped in the ranks. One single cannonball, slicing down the line, knocked the muskets out of the hands of a whole platoon.

As always the ranks did not break. The gaps were filled; there was no check.

The ranks of cavalry with standards carried in the center of each unit moved into the trot. Always officers had to be careful not to take them too fast too early, so that the horses were not tiring as they struck the enemy. They began to canter, sabers still resting scabbard down on their thighs, points up. The trumpets sounded the charge. The dragoons spurred their horses, leveled their sabers and galloped across the road at the waiting lines of rebels.

The volley came late, at short range. Men slipped from their saddles; horses crumpled. But the others went on riding hard onto their target, easing their weight back onto their buttocks as they struck. They broke the line, sending the rebels reeling back toward the gorge, and captured Colonel Nathaniel Ramsay, one of their commanders.

It was not so easy for the infantry on the other side of the road. They charged the rebel line behind the fence and were fought back. They charged again with the bayonet, and again. At last, they broke them and forced them, too, back to the ravine, but the stand had achieved its object: Washington’s lines were established behind the gorge.

At this stage, when all the rebels had been driven from the territory between the ravines, Clinton “had no intention of pushing the matter further.” Clearly it would be unwise for him to take on the whole Continental Army, supported by militia, with 6,000 men. Within the limits of the gorges, the battle had been practical, as his men had proved, because Washington could not use his superior numbers.

So the British general planned a withdrawal to the heights on the Freehold side of the ravine behind them, and to cover this move, he had of course left the Hessian troops there posted in strength. But unfortunately—and “impetuously”—the light infantry had advanced far too far on the right and were attacking the left wing of the main rebel army. Clinton ordered them back, but their retreat would have to be covered if they were not to be isolated.

This did not appear too much of a problem. The British were in possession of the whole east side of the ravine, and a row of guns had been set up to counter a rebel battery just across the gorge. Clinton gave instructions for the British positions to be held until the light infantry had dropped back, when the whole withdrawal movement could be put into operation, and rode back to his headquarters that once again had been set up in the Monmouth Courthouse.

So far as the general was concerned, the battle was over, and since he had driven the rebels in retreat before him, he regarded it with some logic as a success. Anyway, “the heat of the sun was by this time so intolerable that neither army could possibly stand it much longer.”

But the battle was not over. Very shortly Clinton had to return. “From my intentions not being properly understood,” his troops had left the covering ground, “and the enemy began to repass the bridge in great force.” At the same time the rebel guns were firing continuously.

Clinton, who was still trying to organize a withdrawal, found himself drawn back into battle on this sweltering afternoon. To cover the retreat of his light infantry, who were pinned down by the rebels’ new positions, he had to order another attack.

Despite the heat the fiercest fighting of the day began and continued, with the guns of both sides firing continuously and a series of bayonet charges by the infantry, until dusk when at last Clinton was able to pull back his army to the heights of Freehold.3

Considering the limited military objectives, it had been an expensive action in casualties for both sides, and enemy fire was not the only killer. Nearly sixty of the British troops died of sunstroke.

Clinton did not give his men much time to recover. The rebels had advanced to the ravine near the village, and their sentries were only a quarter of a mile from the British lines. Washington was planning to attack the next morning.

Fortunately the moon that night was only in the sky for a few hours; before eleven it was dark. At midnight Clinton’s soldiers started marching— in silence, stealthily, one battalion at a time. By daylight the next morning the only British who lay between the rebels and Freehold Village were the wounded, left there with a surgeon under a flag of truce. And the dead. And fifteen American prisoners.

By then the troops had caught up with Von Knyphausen and the baggage train, and at ten o’clock had reached the safety of the high ground at Middletown.

The next day the army reached Sandy Hook; and the ships of the fleet, which had sailed up the coast from Philadelphia, began the ferrying operation through the Narrows to New York. By July 5 the operation was complete—but only just in time. For that day, the Comte d’Estaing and his battle fleet arrived off the coast of Virginia. On the eleventh, with twelve ships of the line and six frigates—as well as 4,000 French troops—he threatened New York.

It was the crisis that had been inevitable ever since the French had recognized American independence. The Cabinet had foreseen it and taken what measures they could to meet it; but none of Admiral “Foul Weather Jack” Byron’s storm-battered ships had yet appeared in coastal waters, and Lord Howe’s little fleet was badly outgunned. He had three ships of the line and three frigates less than D’Estaing—only 534 cannon against the 834 that the French could deploy.

Meanwhile, Washington was marching the Continental Army to the Hudson; together with Gates’ troops he had some 20,000 men. During those few days in July, the future of the British in New York seemed very bleak.

In a straight sea battle, Howe would probably have lost any conflict with D’Estaing. But he was stanced for defense just outside New York Harbor in restricted waters featured by a shallow sandbar that, as the British captains knew from experience, was hazardous to big ships.

Howe adopted a classic plan. A small advanced squadron was positioned to fire at the enemy as they felt their way over the sandbar. The remainder were anchored in line in the channel, so that as the French ships approached the Narrows, they would have to run the gauntlet of multiple broadsides.

For eleven days the two fleets lay anchored in sight of each other. Then, on July 22, with a following wind and a high spring tide, the French weighed anchor and began their approach to the harbor. But on closer investigation, D’Estaing’s pilots advised against attempting the bar with the bigger ships. The French admiral hesitated, then called off the attack; his fleet went about and made out to sea.

During the next few days, four British warships arrived in New York from various directions—including the first of Admiral Byron’s unhappy fleet. Howe guessed that D’Estaing had sailed for Rhode Island, where the rebel General Sullivan was threatening the British garrison. With his new reinforcements, even though he was still marginally outgunned, the admiral felt strong enough now to challenge the French in open waters.

He arrived off Rhode Island on August 8 just as the French ships had entered the passage to Newport. D’Estaing, nervous of being blockaded, made a run to sea under a north wind, and for two days the two fleets maneuvered, until a gale scattered them. As the weather eased, several independent actions were fought between individual ships with inconclusive results.

Both admirals gathered their ships and assessed the damage. Howe returned to New York, D’Estaing made for Boston—robbing General Sullivan of the support he needed for his attack on Rhode Island—but by then British transports were approaching up the internal waters of Long Island Sound with Clinton and a relief force. To avoid being cut off, the rebels were forced to withdraw to the mainland. For the time being Rhode Island had been saved.

Howe followed the French to Boston but arrived there to find D’Estaing’s ships lying safely under the unassailable cover of the guns of the town.

The British fleet returned to New York, where the morose admiral, “Black Dick,” gave up his command to sail to England. For this he was criticized; but the Howe family reputation was at stake, and his presence as its senior member was much needed.

His brother had not been welcomed home as the winner of battles—for they had not achieved their object—and in the bitter aftermath of Saratoga, the court and the government were cool. Anonymous writers, both in the press and in pamphlets, were sniping at him constantly, lampooning his delays, his failure to follow through his battles and, inevitably, his decision to go south instead of north up the Hudson to meet Burgoyne. Soon he was pressing for a court of inquiry so that he could present his defense, but the government was not keen to stir muddy waters that would inevitably present the opposition with more ammunition.

Meanwhile, in New York, tension was easing. The mood was similar to that of London after the recent confrontation of the French and British Channel fleets. The challenge of the rebels’ new and powerful ally had been met. It would come again, but for the moment the point of crisis was past. There was time for preparation.

Clinton had carried out the main part of his orders from Germain; he had retrenched in New York. Plans had either been executed or were in hand for reinforcing Florida, Canada, Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. Very carefully, the British once more moved onto the offensive in a minor way.

In November two troop convoys sailed south under fleet escorts with orders to attack. One, under the command of General Grant, was steering for the West Indies, which the Cabinet in London believed would be the main center of action on the American side of the Atlantic.

The other, under Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell, was carrying a force to invade Georgia—the last of the American provinces to send delegates to the rebel Congress and a possible springboard for a future campaign to recover the South, a possibility always being discussed optimistically in London.

Both missions were completely successful. By January the British had taken the strategically important French island of St. Lucia—and fought off a determined attempt by D’Estaing to recover it—and had driven the rebel opposition out of Georgia.

The news fed the new temporary mood of optimism in St. James’s and Whitehall. Following the King’s demand for “activity, decision and zeal,” Germain bombarded Clinton with letters that infuriated him urging offensive operations. To the general, London was being completely unrealistic; he was expected to conduct the war with the kind of aggressive planning that Howe had been able to display, and yet his force had been stripped by detachments. For a man like Clinton, with his erratic moods that varied from deep pessimism to occasional jaunty optimism, it was too much. Repeatedly, like Lord North, he asked permission to resign, and, like those of the Premier, the requests were refused.

In fact, Clinton was just as keen as Germain to be ambitious in his campaign planning. The success in holding off D’Estaing had, he believed, soured the rebel view of their new allies and created an opportunity for Britain. Many Americans were tired of the conflict that had now been in progress for so long. “One vigorous campaign,” he wrote, “tout sera dit.” But for this he needed many more men. It was the same old cry that Howe had made so persistently; though with his reduced forces, Clinton had more reason for complaint than his predecessor.

In flattering letters Germain tried to soothe his prickly general, but he still could not help nit-picking and interfering. Clinton exploded. “I am on the spot,” he wrote home angrily at one moment. “The earliest and most exact intelligence on every point ought naturally, from my situation, to reach me. . . . For God’s sake, My Lord, if you wish me to do anything, leave me to myself and let me adapt my effects to the hourly change of circumstances.”

And he was not doing badly. Apart from the military aspects, his secret agents were digging away at the foundations of the rebel army. To William Smith, New York’s chief justice, he confided that he expected to be “presented soon with the heads of some of the Rebel leaders.” He was in direct touch with at least two of them who were smarting under heavy-handed treatment by Congress—Philip Schuyler and Benedict Arnold.

Also, under prodding from London, he was at last promoting the recruitment of Loyalists with a degree of enthusiasm. Although some American units such as Simcoe’s Queen’s Rangers had fought extremely well, the British had always been lukewarm about the Loyalists. But now, short as they were of troops, they began to tap this enormous source of bitter manpower.

For the first time Loyalist officers were put on the same pay scales and rank hierarchy as the British regulars. Some effort was made to exploit the Americans’ countries of origin. An Irish unit was established, and a Scottish group and a Roman Catholic corps. A whole Loyalist regiment comprising both infantry and dragoons was set up around the nucleus of the Queen’s Rangers under the title the British Legion. Wearing green uniforms, its colonel was nominally Lord Cathcart, but its active commander was a ruthless but spectacular lieutenant colonel of cavalry who was only twenty-three, Banastre Tarleton. Tarleton’s Legion and in particular his Green Dragoons were to play an important and even brilliant part in the fighting that lay ahead. As a highly mobile assault unit, it was especially formidable because, unlike the British and the Hessians, its troops hated their rebel enemies with a fierce intensity.

The early persecution of the Tories had grown far more vicious. At Bennington surrender had been refused to many who were killed in cold blood. After the evacuation of Philadelphia two Loyalists had been hanged. During the fighting in Georgia, several loyalist American prisoners had been executed summarily by the rebel troops; this, in turn, had provoked retaliation in kind by Tory commanders. Branding on the hand was an accepted punishment meted out by rebel courts. Responding to Clinton’s desperate need for men, the Tories were to contribute a great deal statistically to his forces. The province of New York alone was responsible for 15,000 men in both the army and navy. In Georgia more than half the British force was American. In addition, the British were now encouraging Loyalist privateering, and they mei a strong response. For apart from the opportunity for fighting the rebels, there was prize money to be made. Advertising posters throughout New York City urged recruits to join the crews of the ships that were fitting out. One of these was the Fair American, the commissioning of which was financed by the “Loyal Ladies of New York.”

In fact, the enthusiasm for privateering was so great that the: navy soon complained it was obstructing manning and provisioning the fleet. Eventually, it took over the whole operation, working with a board of directors consisting of the leading Loyalists from each province. The British fitted out the ships while the board supplied the officers and crews. The fleet of Associated Loyalists was soon harrying the New England coast.

Through much of 1779, Clinton put his Loyalists to full use—though he found them hard to control. Shadowed as it was by the new developments in Europe, it was a year of small operations, of raids and counterraids.

In the North the two men who had run the ambush at Oriskany, Colonel John Butler and Thayendanegea, the Mohawk chief, swooped through Wyoming and upper New York with mixed forces of Tories and Indians displaying a level of brutality that was to be a great embarrassment to the government in London. The rebels soon retaliated; within months General Sullivan was leading an expedition in revenge against the Six Nations of the Iroquois League, of which Thayendanegea was a leading chief, deploying methods that were hardly less brutal.

From New York Governor Tryon led a series of raids on the seaport towns that provided the bases for the rebel privateers. The regulars went raiding, too. So, for that matter, did Washington; his men recaptured the Hudson fort at Stony Point, taken by the British, and seized the garrison of Paulus Hook just across the river from Manhattan.

For the most part the clashes were not too serious. It was, in fact, a period of pause while the effect of the French Alliance and the imminent entry of the Spanish into the war was assessed.

The first winter months of 1779 had been hard, and the Hudson had frozen, which caused Clinton to expect a rebel attack on New York across the ice. The Continental Army was very close—at Morristown in the Jersey hills where it had spent the cold months after Princeton in 1777—but no assault came. Washington, too, was doing his assessing and certainly, surmised Clinton, could not have been too encouraged by the first French efforts.

The sense of euphoria that marked the British in both London and New York in the spring of 1779 did not last long. In June they faced crisis again on both sides of the Atlantic. The Spanish ambassador in London handed Lord Weymouth a belligerent note that, like the French action the year before, was the equivalent of a declaration of war. By the end of July an invasion fleet of ships of both nations had sailed for Britain from Corunna in northern Spain, while at the two French ports of Le Havre and St.-Malo an army of 31,000 men was assembled waiting to be ferried across the Channel under the guns of the warships.

By halfway through August the enemy vessels were anchored in the Channel off Plymouth. So far they had been unchallenged by the British Home Fleet, which was far to the west under the command of Sir Charles Hardy. Poised ready to block the way to Ireland, the expected assault point, it had been borne out into the Atlantic by an east wind.

The fact that they did not know the position of the British fleet made the enemy commanders nervous, and they weighed anchor and went looking for it. By the time they made contact, Hardy’s ships were in the Channel heading for Portsmouth—between the enemy and Britain. The invasion had been hurriedly organized. There had been delays at Corunna; many of the ships needed revictualing. The French and Spanish commanders decided on postponement and returned to their home ports. Britain had survived yet another threat.

Across the Atlantic, however, a French offensive had produced a new crisis. St. Vincent and Grenada, one of the richest of the sugar islands, had been taken, and the fleet was assembling at Santo Domingo in obvious preparation for a strike at Jamaica.

As soon as Clinton heard the news, he sent Cornwallis with 4,000 troops to reinforce the island’s garrison. On the way the earl learned that D’Estaing and the French fleet had left Santo Domingo—but not on course for Jamaica; they were steering north. New York could again be the target, so the troop convoy turned about and made back to British headquarters. But D’Estaing was not aiming for New York, at least not immediately, but for Savannah, Georgia. On board his ships he had 6,000 French troops ready to cooperate with the rebel General Benjamin Lincoln who was marching on the town overland from Charleston in South Carolina.

Outnumbered as the British garrison was by two to one, its prospects were very poor. For six weeks Savannah lay under siege. The town was bombarded by D’Estaing’s guns and eventually stormed at dawn on October 9. But the British fought off the attack, inflicting heavy losses, until the French admiral, fearful of the seasonal gales, reembarked his troops and withdrew. Lincoln and his rebels had no alternative but to march back to Charleston.

To Clinton in New York it was the signal for Britain to move once more onto a major offensive to break the Revolution. By calling off the siege of Savannah, D’Estaing had left him the base that was vital to further operations in the South. “I think this is the greatest event that has happened the whole war,” Clinton wrote in one of his moments of enthusiasm that interspersed his periods of gloom.

The timing was right. Admiral Marriott Arbuthnot, an irascible seventy-year-old who had arrived with a new fleet to take over the naval command, had brought reinforcements. Sooner or later Georgia would surely be retaken unless he could support it; this meant occupying neighboring South Carolina.

But Washington appeared to be anticipating his thinking. The defenses of Charleston, the seaport capital of the province, were being strengthened, and Clinton’s agents reported that the rebel commander was planning to send down a reinforcement of 2,000 men. So the British general decided to act quickly before the rebel arrangements were complete. He made hurried plans to attack the port with every man he could spare.

Since Saratoga, british policymaking in Whitehall had been centered on the South. The concept of military subjugation had now been replaced with the long-term plan of returning as large an area as possible to civil government with each province supplying delegates to what (eventually) would be a kind of Loyalist congress. The aim was to copy Washington’s successful technique, deployed brilliantly before Saratoga, of employing local militia to operate in their own territories in times of crisis, with support when necessary from a small full-time army. London hoped this would help deflate the Revolution, which, to judge from what Clinton and others had reported home, already seemed to be occurring.

The focus of the new thinking was centered on the Southern colonies whose wealthy plantation families tended toward Loyalism. They had been slower than the Northern provinces to join the revolt, and although they had been a large source of supplies to the rebel army, Florida’s Governor Patrick Tonyn had reported that now the British naval blockade of their coast was making them “sick of the opposition of Government.” Also, they were in no mood to fight. “I am certain,” wrote Tonyn, “the four southern provinces are incapable of making any very formidable resistance; they are not prepared for a scene of war.”

Clinton’s plans to put this statement to the test involved a risk that had existed in no other campaign in America since Lexington. He would have to supply the army by water; until Saratoga Britain had always retained command of the sea. Now with a permanent threat from French and Spanish warships, this was no longer so certain. But both New York and London saw it as a calculated speculation.

Clinton gave the final orders, and an army of 8,000 men was embarked.

At noon in brilliant sunshine on Christmas Day, Clinton and Cornwallis boarded a ship and ran out through the Narrows filled with drifting ice. The fleet, already waiting at Sandy Hook, weighed anchor and sailed south for Charleston.