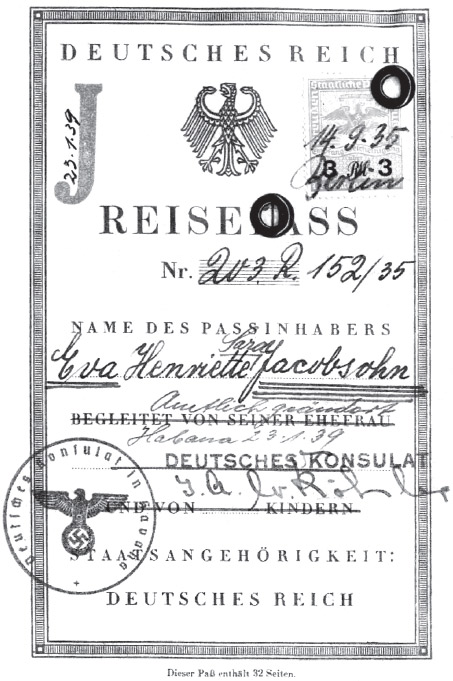

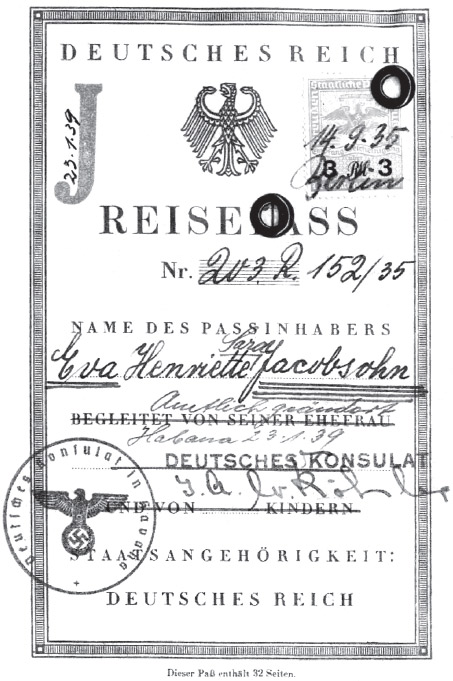

Eva’s Nazi-issued passport. Between August and October 1938, all legal documents were stamped “J” for Jew, “Sara” for all Jewish females and “Israel” for all Jewish men. Courtesy of the Eva Loew collection.

Chapter 21

EVA’S ESCAPE

Anti-Semitism in Germany blatantly increased. Emigrating was becoming more difficult, and taking one’s possessions and money out of the country was nearly impossible, but the Jacobsohn family had help. During World War I, Dr. Jacobsohn made a promise to a dying patient that he would look after the soldier’s wife and two sons. He kept his word, and in the years that followed the war, he became a surrogate father to those two sons. When Hitler came to power, Eva’s father advised the eldest son to accept a commission as a SS officer. In the late summer of 1938, that officer appeared at the Jacobsohns’ door under the cover of night. He was nervous. His words were straight to the point: “Get out of Germany, now.” He had risked much to convey that warning. If he were seen aiding Jews, he certainly would have lost his commission, and perhaps worse. But he did risk it all. His debt of gratitude to Dr. Jacobsohn for taking care of his family transcended military duty and Nazi Party affiliation. To that officer, the Jacobsohns were not just Jews; they were family.97

As the situation for Jews worsened, the Jacobsohns housed desperate relatives and friends who had lost their homes and incomes. Mrs. Jacobsohn was the family decision-maker. She was the one who sensed the gravity of the situation early on and now determined it was time to leave Germany as soon as possible. The visit from the SS officer finally convinced her husband, though he was still hesitant. If it were not for Eva’s mother, the family would never have left, and they probably would not have survived the Holocaust death camps of the 1940s. She responded to the deteriorating chaos with resolve. She procured the exit visas for Eva and her sister Hannah and packed the items they should take with them. She supervised the packing up of the household items in large wooden crates that she wanted to take to the United States. Exit visas were almost impossible to obtain as tens of thousands of Jews tried to leave Germany all at once, but a patient of Dr. Jacobsohn’s worked in the visa office and expedited the necessary paperwork to provide exit visas for the family members. He, too, had to function secretly beyond the sight of the Nazis.

On August 22, 1938, Eva and Hannah walked out the front door of their home and locked the door. Their parents had left for Cuba several days before. They each carried a suitcase. Eva’s was heavy because she had stuffed it with what she loved most: her books. They walked down their tree-lined sidewalk as if nothing peculiar was happening, as if the two were leaving on an ordinary vacation or a visit. Not even stopping, they turned to glance back at their home for the last time before they turned the corner.

From Berlin, the two sisters flew to Zurich, Switzerland. They could not travel through France because it would have taken too much time to obtain transit permits. They stayed with family friends for a few weeks and then flew directly to England. There, they reunited with Eva’s elder sister, Ruth, and her younger brother, Heine, in London. In England, everyone carried a gas mask because the population expected war to break out at any moment.

Eva and Hannah boarded the Holland-American ocean liner the Statendam on October 1 and set sail for America. Her parents had telegrammed the girls earlier from Cuba that they should rejoin them there, for that is where they were granted entry. For the present, Ruth and Heine were to remain in England.

The ship slowly turned from the mainland and ventured out to sea. On the deck, the passengers gazed back at the landmass as its details of buildings, moored ships and coastline contours faded into a phantom cloud of mist. The ship rocked, as if to remind the passengers that their familiar human home on solid ground no longer existed. They were now in an alien world that had no resemblance to the life that anchored them before. This was a universal response, but for Eva, the reality had particular meaning. She was once again in exile, but not like before when she was in England and could return home. Now there was no home to return to. As she held on to the rail, peering off into the distance, she reached for her pocketbook that was slung across her shoulder. She grasped her passport and looked at it for a long time. It was her ticket to freedom. The Nazis had amended it. She focused on the red “J” for Juden, Jew, and the name given to all Jewish women, “Sara.” She muttered an anguished question that no one could hear except herself: “What on earth have we all done, that now things are so hard instead of living in peace?” She talked to herself: “You can’t change things when circumstances are stronger than what you can do. You can’t put your head through a wall because the wall keeps standing there, and all you do is get a bloody head. In Breesen, we used to say K.S. Keep smiling and make the best of it.”98 She acknowledged the anger that came over her. What did the Nazis know about her? All they saw was that she was a Jew, not even a German anymore. But she now possessed a plan: the Virginia Plan. She vowed not to look backward.

On the first day out to sea, off in the distance, “the sky ahead was a drab lilac color, but overhead the sun was still shining. The water had a very dark blue green color, and every place the whitecaps were blinking…The [wind] roared so much throughout the masts that you really couldn’t hear your own words.”99 It was a threatening sign when the crew bolted down the heavy iron covers of the portholes. Then the storm hit. The waves rose with each new wind gust. Deck chairs slid from one side to the other. One woman’s raincoat was ripped right off her from the wind. Sea spray exploded every time the bow cut through a rolling wave. The passengers scurried to their rooms. At night, the hall that was scheduled to host the gala departure party was almost vacant. Waiters stood around with nothing to do, but Eva could eat even as others were deathly seasick.

Eva’s Nazi-issued passport. Between August and October 1938, all legal documents were stamped “J” for Jew, “Sara” for all Jewish females and “Israel” for all Jewish men. Courtesy of the Eva Loew collection.

The storm worsened. At one point, the ship cut its engines and tossed helplessly. Its forward motion had stopped altogether. Water had flooded the engine room, and all hands were ordered to man the pumps. The ship dropped into the deep caverns between the wave crests, so low that one lost sight of the horizon. It was totally unnerving to look to the side of the ship and see nothing but a wall of ocean. Some of the waves reached gigantic heights taller than houses. This had all the earmarks of a hurricane. The passengers were sick and frightened, but Eva found the entire experience thrilling, though scary. In her diary, she wrote, “With the storm, you realized that nature does not let itself be controlled by man. Such a great force makes people completely helpless.”100 This was a tumultuous beginning to her new life.

The voyage that began with such ferocity ended in the quiet calm that follows a storm. As the sun broke through the clouds, the passengers timidly appeared on deck. Most had never met the other passengers because they had stayed in their rooms throughout the storm. At night, Eva stood at the rail and studied the night sky. “The moon was out…pieces of clouds shot by the moon…the strange coloring of the ocean was actually unbelievable.”101 As the ship entered New York Harbor, Eva marveled at how everything looked “exactly the way one saw it in the movies or the way it was written about in books. The Statue of Liberty really looked small next to the skyscrapers.”102 As the passengers disembarked, the two sisters became stuck in bureaucratic quicksand. For seven hours they tried to clarify to the authorities that they possessed transit visas, good for only four days staying in the United States, before they traveled to Cuba. Eva’s aunt waited for the girls on the pier; they were the last to leave the ship. They were exhausted but relieved that the longest part of the journey was over. In a few days, they would board a banana freighter, the SS Mexico, which carried only sixty passengers, and travel south to reunite with their parents in Cuba.

The night they left New York Harbor, a thick fog bank enveloped the boat. Every two minutes, the ship’s foghorn blared. Falling asleep was impossible. Nevertheless, Eva was falling in love with sailing. The first day out, the ocean was a mirror, and it was hot. As the day proceeded, rain clouds appeared on the horizon. The sun reflected off the raindrops and formed the most beautiful rainbow that Eva had ever seen. The sunset was extravagant with deep reds, yellows and then dark green and finally night blue. As the sunset lingered in the west, Eva relaxed in a deck chair outside her cabin. “The wind started up and light and dark clouds with strange configurations went by so that [she] felt like a witness to a giant theatre production.”103 To Eva’s surprise, the night air did not cool down. Every mile traveled south brought the boat closer to the heat of Cuba.

In just a matter of weeks, Eva had traveled through a world of contrasts. She felt like she was on a carousel, and as her imaginary, galloping horse circled around, she scanned the painted scenes of distant and exotic lands. Indeed, she was on a merry-go-round: first Germany and then to Switzerland. Then in the air to England and an ocean journey to New York. Next, the slow sailing into a completely different climate heading south to Cuba. All this within just two weeks.

The banana boat sighted the island of Cuba. At first, it was just a dot floating on the horizon that bobbed up and down, but as the boat approached the island, it loomed larger and the ocean seemed to shrink. Eva knew that she would be entering a new world of smells, colors, trees and flowers, music and people who spoke a language she did not understand. Her parents met the boat with smiles of relief. Their daughters had made the trip safely, and now they were together again, even though they were in a strange new land.

CUBA

Instead of feeling insecure and strange, Eva was invigorated by every new experience that Cuba offered. Dr. and Mrs. Jacobsohn had friends in Cuba who embraced them warmly and introduced the family to the Cuban way of life. On the first trip out to their farm, the three-hour train ride afforded Eva a view of the countryside. She saw sugar cane fields for the first time, and she noticed that the soil was rust-colored. The train passed through villages, orange and lemon groves and beautifully tailored gardens managed by Chinese farmers. There were pastures and fields where horses and cows were grazing. “Far away, [one] could see the mountain range and the sky was lit up in unbelievable colors as the sun was just going down. It was unbelievably beautiful, this picture of big royal palm trees silhouetted against the fiery evening sky.”104 After the train ride, the guests climbed onto oxen-drawn wooden carts with two huge wooden wheels. The jarring ride over pot-holed dirt roads took an hour and a half. The friends’ single-story farmhouse was located at the edge of a small village. After the guests settled in and ate supper, Eva went outside before going to bed. As she wrote in her diary:

There was really a very eerie quiet and stillness about the land. It was very dark, so one could see all the stars which certainly [could not] be seen in the city. The stars here seem to have a much stranger and brighter glow than in Europe, and that’s how you know that you are really completely somewhere else. The moon doesn’t stand in the sky, but is lying down which at first is a very strange sight. Especially clearly we could see the Milky Way and then we went to bed.105

Her sleep ended early in the morning when roosters crowed. After breakfast, Eva observed cowboys on horseback bringing the cows and their calves to a barn. She watched with fascination as the calves began to suck the mothers’ teats, but then they were pulled away and the cowboys milked the cows for the milk that was needed for the day. Eva could not contain herself and jumped in to milk a cow. The men watched in astonishment, for here was a “city girl” who knew exactly how to manage the cow and milk it efficiently. After her show of skill and familiarity, the men clapped in appreciation.

One new experience followed another. Eva rode a horse for the first time and loved it. She was a natural as she learned to trot and gallop. As she rode past small farms, she realized how poor the people were. They had nothing, not even shoes for the children, but she mused to herself, “So much missing for them, and yet they are content.”106 Eva’s world was expanding. She came from a cosmopolitan life in Berlin and London to the castle farm of Gross Breesen and now to the primitive countryside of a third world country. Everything interested her. She rose early to view the tropical sunrise and then investigate the big pumping stations for irrigation and study the giant diesel motor that ran the pumps. She reveled in the slower pace of the life and the music, and she marveled at the natural dexterity of the natives dancing the rumba. She walked into a field and broke off a piece of sugar cane, peeled off the hard skin and sucked the sweet marrow. She asked questions about growing sugar cane and was impressed that after each harvest, the fields were burned and the soil was turned under and allowed to sit for several years before another crop was planted. She loved the Cuban landscape, especially the open fields, the caves and the beaches with the seashells and multicolored jellyfish. She was fascinated by the agave plant from which rope was made. The family visited Catholic churches and marveled at the pictures and sculptures of the saints. One young priest impressed Eva: “When he was talking about holy things, his face was uplifted unbelievably beautifully.”107

In late January 1939, Eva’s mother received her U.S. visa and immediately traveled to Miami to go through immigration. This meant that Eva and her sister were automatically granted visas and they could immigrate to America. “It is a wonderful feeling to know that the period of waiting is now at an end. And I can hardly wait for the time when we finally leave.”108 The plan was that Eva’s mother would take her two daughters to Miami; Hannah would then travel to Texas to a family that would take her in, and Eva would go to New York to collect her baggage and then travel to Hyde Farmlands in Burkeville, Virginia. Dr. Jacobsohn could not enter the United States because he technically was of Polish nationality and had to wait for a Polish visa. He was eventually aided in his application by a Quaker organization in the United States and by a supporting letter sent to the State Department by the famous Albert Einstein, a friend of Jacobsohn.

Eva discovered her love of horses during her short stay in Cuba. Courtesy of the Eva Loew collection.