In sixteenth-century Europe, tapestries were markers of wealth, status, power, and cultivated taste. More expensive to produce and more prestigious than paintings, these “woven frescoes” were at once signs of splendour and artistic commodities that circulated within an aristocratic culture of consumption. Their dazzling scenes commemorated notable deeds from a distant past, like Alexander the Great’s conquests, and more recent ones, like Charles V’s victory at the battle of Tunis (1535). They retold all manner of tales – mythological, religious, historical – and they could serve as purely decorative objects. Whether they hung in the chambers of kings and nobles or in public arenas, tapestries played a prominent role in the art, propaganda, and ceremonies of church and court.1 In this essay I examine the tapestries woven by nymphs in Garcilaso’s Third Eclogue as lyric versions of the figurative tapestries of the period and as objects that, like many actual tapestries, served as gifts for social and political networking with patrons and powerful others, in this case María Osorio Pimentel, vicereine of Naples, to whom the poem is dedicated.2 What makes these lyric weavings so striking is that they appear en abîme within a poem itself conceived doubly as a fabric: as an interweaving of textual fragments from ancient and contemporary Italian works, and as a text on paper [carta], a sheet of matted fibre on which the poet’s quill [pluma] inscribes and thus preserves the memory of María.

In an age thoroughly imbued with the dynamics of networking, making and maintaining social connections “became something of an art” that deeply implicated the self (McLean 2007, 4). Perhaps no one understood that better than Baldassare Castiglione, papal nuncio to the Spanish court (1524–9), whose book of manners, Il Cortegiano (1528), was translated into Spanish by Juan Boscán with Garcilaso’s polishing touches and prologue (1534). Castiglione reveals elegantly the interplay between the art of networking and the construction of the self. His courtier, far from autonomous, shapes an identity through masks donned in staged public performances while interacting with those in high position (1959, Book 2). Garcilaso, an equally keen observer of social manoeuvrings and gift-giving in his own circles, figures himself in the eclogue as grateful friend and flattering courtier, but also as a skilled verbal craftsman of four sumptuous tapestries for the vicereine, whose court at Naples had sheltered him during his exile from the imperial court (1532–6).3 The poet’s luxurious gifts in turn figure María as a discerning member of a literate culture.

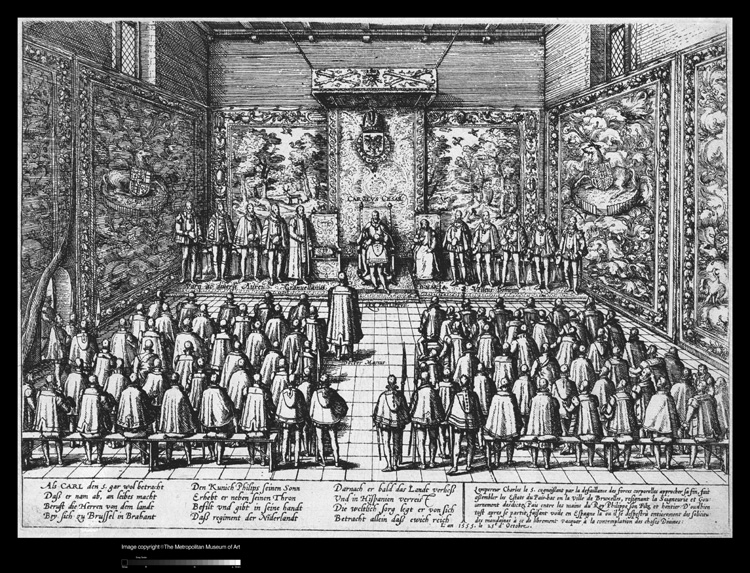

In the heartland of tapestry production in the Low Countries and northern France skilled artisans crafted the most expensive and highly sought weavings in silk, silver, and gold thread that circulated throughout France, England, Italy, and Spain.4 They were an ideal medium of ostentation to parade monumental images of ancestors, military campaigns, and historical or mythological figures with which a patron wished to be associated (Campbell 2002, 15). The most affluent patrons commissioned sets of related tapestries, called “chambers,” which typically covered a room’s interior walls from floor to ceiling. An engraving by Frans Hogenberg, ca. 1558, The Abdication of Charles V (see fig. 1) shows how a chamber of tapestries set the stage for that historic event: Charles is surrounded by his heraldic devices – most prominently the stag – and behind him hangs his coat of arms, below which is inscribed “Carolus Caesar.” Marketing visual imagery for propaganda, just as his grandfather Maximilian had done so successfully in his own time, Charles exploited the symbols embedded in the tapestries to enhance imperial authority on behalf of his son Philip and his brother Ferdinand, who would carry Habsburg rule forward.5

As a member of Charles’s court, Garcilaso would have been familiar with these imperial trappings, especially when displayed conspicuously on festive occasions at home and abroad, notably during the emperor’s coronation by Pope Clement VII in Bologna in 1530, which the poet witnessed. At a time when royal households itinerated for seasonal and political reasons, tapestries became the ultimate transportable emblem of wealth and power, as essential to a Christian prince as his portable altars. An inventory taken in 1544 of Charles’s Removing Wardrobe, as portable tapestry collections were called, listed fifteen sets comprising ninety-six tapestries, the most prized being the spectacular nine-piece chamber, Los Honores (1520s), an allegorical celebration of Habsburg values and a kind of “mirror for princes” because of its moral content (Delmarcel 2000). The seven-piece Battle of Pavia, commemorating Charles’s victory over Francis I (1525), remains one of the most important chambers in the imperial collection (see fig. 2). For the wedding of Prince Philip to Mary Tudor (1554), Charles sent his twelve-piece Conquest of Tunis tapestries to hang in Winchester Cathedral. That formidable set, a visual tour de force, celebrated Habsburg prestige and magnificence. But if the display of tapestries indexed a ruler’s status and authority, the lack of tapestries reflected just the opposite. When in 1527 Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, visited Pope Clement VII, then in exile in Orvieto following the sack of Rome, it was the absence of tapestries that first drew his attention. “Before reaching [the pope’s] privy chamber,” he reported, “we passed three chambers all naked and unhanged” (cited in Campbell 2002, 4). Living within bare walls, the pope was as undressed of authority as his chambers were of tapestries.

Figure 1 The Abdication of Charles V from Events in the History of the Netherlands, France, Germany and England between 1535 and 1608. Impression of an engraving by Frans Hogenberg, ca. 1558. The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY.

The eclogue’s four discursive tapestries, like a chamber of actual hangings, are linked by style, iconography, and subject matter – the violent loss of a loved one and an abandoned, grieving lover in the mythological tales of Apollo and Daphne, Orpheus and Eurydice, Venus and Adonis, and the pastoral story of Elisa and Nemoroso. They recall the decorative hangings known at the time as verdures and now often called millefleurs. Characterized by foliage arranged in “repeating patterns of flowers and plants, enlivened with animals and figures in more elaborate pieces,” they made up the majority of tapestries in quotidian use, particularly in private, intimate settings (Campbell 2002, 24). The Diccionario de Autoridades fittingly offers the plural “verduras” for these designs: “Llaman en los paises, y tapicerías el follage, y plantage, que se pinta en ellos” [Called in paintings (of villas, country houses, or countryside) and tapestries the foliage and plants that are painted in them]. Garcilaso plays with the technical term in the singular “verdura” to describe the stylized, bucolic setting of the banks of the Tagus, where the nymphs execute their craft:

Cerca del Tajo, en soledad amena,

de verdes sauces hay una espesura

toda de hiedra revestida y llena,

que por el tronco va hasta el altura

y así la teje arriba y encadena,

que’l sol no halla paso a la verdura.

[Close by the Tagus, in pleasing solitude,

there is a stand of willows, a dense grove

all dressed and draped with ivy, whose multitude

of stems goes climbing to the top and weaves

a canopy thick enough to exclude the sun,

denying it access to green leaves below.]

(57–62, my emphasis)6

Figure 2 Surrender of Francis I from the Battle of Pavia tapestry series. Bernaert van Orley, woven in the Dermoyen workshop. Brussels, ca. 1528–31. Wool, silk, and silver. Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples. Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY.

“Verdura” is joined by the metatextual “teje,” by means of which nature weaves its own thick, complex patterns. The ground is covered with flowers: “el suave olor de aquel florido suelo” [the subtle scents arising from the flowery field] (74; my emphasis). “Verdura,” “teje,” and “florido suelo” announce a kinship between the textual setting and actual millefleurs tapestries, presaging the plant and floral weavings fictionally destined for María’s quarters: the snake that bites and kills Eurydice lies hidden in the grass and flowers [entre la hierba y flores escondida] (132); the blood oozing out of Adonis’s chest, torn open by the boar’s tusk, turns red “the white roses that beautified that spot” [las rosas blancas por alli sembradas] (183); and a decapitated Elisa, metaphorically echoing the floral setting, “cuya vida mostraba que habia sido / antes de tiempo y casi en flor cortada” [whose life has clearly been cut short before its day, / just as the bud was coming into flower] (227–8), appears in a flowery spot (229), lying among the blades of green grass (231–2).

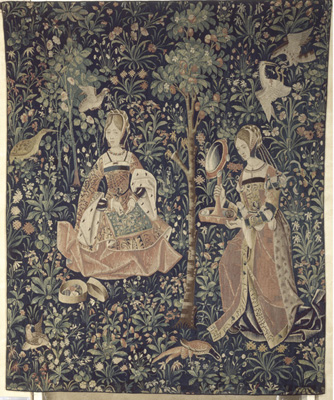

Millefleurs were eminently suited for a vicereine in accordance with contemporary tastes in weavings, their place in private vs. public spaces, and in certain cases gender-based themes as the following anecdote suggests. When Philip the Fair and Juana of Castile visited the Château de Blois in 1501, they found it filled with tapestries and cloths of all types. Louis XII had hung his grande salle with The Destruction of Troy and his dining room with The Battle of Formigny, scenes celebrating military events, much like Charles V, who displayed tapestries to reflect his imperial status and magnificence for political purposes. By contrast, the queen, Anne of Brittany, had her private quarters at Blois hung with tapestries akin to millefleurs, depicting “beasts and birds with people from distant lands,” while her daughter Claude had her room hung with “a very beautiful bucolic tapestry filled with inscriptions and very small figures” (Guiffrey 1878, 67). At Naples the palaces of the vicereine and her husband were richly decorated with hangings, including millefleurs according to an inventory taken in 1553.7 When the ambassador from Mantua, Nicola Maffei, visited the capital in 1536, he found the walls of Castel Nuovo covered with tapestries: “tapezarie fine et bellisime et vanno attacate fin alla volta delle camere” [elegant and most beautiful tapestries were hung up to the vaulted ceilings of the rooms] (cited in Hernando Sánchez, 1993, 51). Most likely the vicereine did needlework – a sister art to weaving – much like her contemporaries Catherine de Medici in France and Mary Queen of Scots, who typically went about their stitching while engaged in conversation (Jones and Stallybrass 2000, 153). We would expect the vicereine to share a bond with Garcilaso’s nymphs, who had previously appeared in Sonnet 11, “labrando embebescidas / o tejendo las telas delicadas” [bowed over your embroidery, / or toiling at the weaver’s delicate art] and taking pleasure in one another’s company, “unas con otras apartadas / contándoos los amores y las vidas” [sitting in little groups apart / making your loves and lives into a story]. A millefleurs tapestry dated circa 1520, now at the Musée de Cluny (see fig. 3), offers a splendid pictorial play en abîme illustrating how aristocratic ladies pursued their favourite activity: one is embroidering a millefleurs scene, while another is carrying skeins of yarn and a convex mirror, which reflects the very setting that is the subject of the embroidery.

Garcilaso knew that according to conventions of tapestry making, only the highest level of craftsmanship and the finest materials, gold being the most luxurious and expensive of threads, were worthy of a vicereine. His nymphs fabricate tapestries from the riches of the Tagus River, transforming nature into culture by turning its grains of gold and aquatic plants into thread, and by colouring their yarn with the purple dye of its shellfish:

Las telas eran hechas y tejidas

del oro que’l felice Tajo envía, […]

y de las verdes ovas, reducidas

en estambre sotil, cual convenía,

para seguir el delicado estilo

del oro, ya tirado en rico hilo.

La delicada estambre era distinta

de las colores que antes le habian dado

con la fineza de la varia tinta

que se halla en las conchas del pescado.

[The fabric of the cloth that they were weaving

was made from gold the happy Tagus gives, […]

and also made from the strands of green waterweed,

converted into a fine warp [yarn], which serves

to complement the delicate style that’s bred

from gold spun out into a precious thread.

The threads they worked were delicate and fine,

subtly coloured with many tinctures,

using the various shades one can obtain

from their origin in shells of the sea’s creatures.]

(105–6, 109–16)

Figure 3 The Seignorial Life: Embroidery, ca. 1520. Southern Netherlands. Wool and silk tapestry. Musée National du Moyen Age-Thermes de Cluny, Paris. Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY.

The gold of the Tagus was legendary – it is mentioned in Pliny’s Natural History and cited by Ovid and Martial, among others (Morros 1995, notes to vv. 105–8, pp. 229, 518) – but purple dye (the most desirable being from Tyre) was no doubt added by Garcilaso to glorify the fertile river. The poet likens the artistry of the weaver-nymphs to that of the ancient Greek artists Apelles and Timanthes (117–20), a comparison justified by the coupling of painting and weaving: “lo que pinta / y texe cada ninfa” [what each nymph paints and weaves] (117–18, my translation).8 The term “pintar” [to paint] appears here as a Latinism, according to Leo Spitzer, since “pingere was used in Latin also of embroidery” (1952, 246). Erwin Panofsky notes that in sixteenth-century Latin the terms pingere, pingi, and pictus refer “to a graphic representation, drawing or print, in contradistinction to a sculpture or metal” (1951, 34, note 1). If we follow Panofsky’s lead, “pintar” (placed alongside “texer”) draws our attention to the cartoon, a drawing used in the weaving process. Joseph Campbell alerts us to its meaning: “Full-scale colored version of the intended designs that weavers copy during weaving. Generally painted on linen until the late fifteenth century. From the early sixteenth century on, cartoons were painted mostly in body color on paper” (2007, 397). Garcilaso does not mention a weaving technique, but we may suppose that given their mythological origins, his nymphs did not use cartoons as guides to weave their pieces.

Beyond dexterity in weaving (vv. 122, 145–6, 169–70), it is their use of perspectivism that serves as a touchstone of the skill of these artisan-weavers, who are well-versed in Renaissance artistic codes:

Destas historias tales varïadas

eran las telas de las cuatro hermanas,

las cuales con colores matizadas,

claras las luces, de las sombras vanas

mostraban a los ojos relevadas

las cosas y figuras que eran llanas,

tanto, que al parecer el cuerpo vano

pudiera ser tomado con la mano.

[Such are the varied stories that were told

in the fine tapestries of these four sisters,

who joined their colors in an artful blend,

with highlights that from the empty shadows

brought forward, as if standing in the round,

objects and figures that were flat and so

you’d think that empty forms were solid and

could actually be taken in the hand.]

(265–72)

Perspectival depth, achieved through chiaroscuro to produce a sense of three-dimensionality, was a valued technique for oil paintings and tapestries alike. Giorgio Vasari, writing from his experience as a tapestry designer, has this much in mind when he describes what was required: “[F]or pictures that are to be woven … there must be [a] … variety of composition in the figures, and these must stand out one from another, so that they may have strong relief, and they must come out bright in coloring and rich in the costumes and vestments” (1996, 2.571). In the eclogue’s tapestries, shaded colours [“con colores matizadas”] converge with bright highlights [“claras las luces”] – Vasari’s “bright in coloring” – to provide an arresting visual display for the vicereine.

By virtue of their portability and splendour, tapestries made for convenient, lavish gifts. When Don Juan’s widow, Margaret of Austria, left Spain in 1499 she reportedly took not only her own collection of tapestries but also twenty-two others as a parting gift from Juan’s mother, Isabella of Castile (Sánchez Cantón 1950, 91, 108–9). We may suppose that these hangings had a diplomatic as well as personal value. Isabella had arranged the marriage of Juan to Margaret and of her daughter Juana to Maximilian’s son and heir, Philip the Fair, for a double wedding celebrated in 1496. Aware of the need to reaffirm her political alliance with Margaret’s father, she found the ideal objects for gift-giving in her large collection of tapestries, acquired through inheritance, purchase, commission, and as gifts (Sánchez Cantón 1950, 89–150, Junquera 1985, 22–5, and Junquera de Vega 1970, 16–22). Garcilaso surely must have witnessed the ritual exchange at court of weavings, needlework, paintings, medals, and precious items such as gems and jewellery. The tapestries of his Third Eclogue belong to this culture of aristocratic gift-giving and networking.

If a soldier and courtier like Garcilaso could not have afforded such an expensive material gift, an inspired poet could “weave’ a set of tapestries worthy of the wife of his patron and protector, Pedro de Toledo, viceroy of Naples. Fernando Bouza documents the early modern practice of gift-giving as a way of keeping friendships and as a sign of deference, a social custom that was defined as “service’: “Generosity was a virtue to be displayed at all times by the [courtier], who, devoid of self-interest … generously served those whom he regarded as his equals or friends or those to whom he was indebted: his superiors or others who had rendered him service with the same generosity” (2007, 153; emphasis in original). Located at the intersection of history and fiction, art and court society, Garcilaso’s cloth gifts were tokens of friendship and gratitude for the vicereine, and for her husband, who (with his nephew Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, Third Duke of Alba) had successfully convinced the emperor to trade the poet’s exile on an island in the Danube for exile in Naples; there, Garcilaso moved easily in aristocratic and intellectual circles, making friends with the likes of Bernardo Tasso, Luigi Tansillo, and Giulio Cesare Caracciolo, and attending the exclusive Accademia Pontaniana. Pedro also recommended Garcilaso for the post of chatelain of Reggio, which Charles readily granted.9 But, as Sharon Kettering points out, the notion of “service” in the giving of a gift, ostensibly a “courtesy” freely offered by the donor, was a “polite fiction” (1988, 135). Something of what Marcel Mauss observed about gifts in archaic societies – items of exchange requiring reciprocity – applies here, for Garcilaso’s tapestry gifts were not totally disinterested. In theory, according to Mauss, gifts are “voluntary, [but] in reality they are given and reciprocated obligatorily.” Apparently gratuitous, they call for a return (1990, 3).10 Garcilaso’s verbal weavings are as much tokens for the future as gifts for past hospitality and protection, a gesture from the nimble-minded courtier to noble friends to keep him in their thoughts for when he might need them again. Within the fiction of the text the tapestries function as a site of exchange procuring a return: his gift for new favours. And of course these magnificent presents would enhance his status and prestige at the Neapolitan court.

Gift-giving functions as a highly personal transaction between Garcilaso and the vicereine, creating an intimacy that further ingratiates the poet to her and reaffirms their friendship. Mauss writes that a gift bears the “soul” or “spirit” of the giver, the hau in Maori gift rituals – “to make a gift of something to someone is to make a present of some part of oneself … In this system of ideas one clearly and logically realizes that one must give back to another person what is really part and parcel of his nature and substance, because to accept something from somebody is to accept some part of his spiritual essence, of his soul” (1990, 12). If we demystify the magical quality of Mauss’s gift exchange, we might say that Garcilaso’s “hand made” gift did indeed embody him, for his tribute to María bears the craftsman’s artifice as a seal, an “imprint” of his identity. The symbolic link between the giver and his gift creates in turn an intimate bond between the courtly giver and his aristocratic recipient.11 Garcilaso’s gifts to María sent in 1536 from Provence, where he wrote the eclogue while “maestre de campo” [aide de camp] of the emperor’s troops facing the army of Francis I, recall the “portrait” letters of the period. In his study of letter-writing customs of the European nobility, Fernando Bouza notes that for those separated by long distances, a handwritten letter was “a second-best substitute for private conversation,” and that customarily a portrait accompanying the letter as a gift served as a “personal contact” to reaffirm a relationship (2007, 154). Bouza cites the letter and self-portrait that Philip II sent to Francisco Barreto as thanks for his support in capturing the rock of Vélez de Gomera in 1564. “I did not know how to pay and thank you,” writes the king, “but by sending you a portrait of myself on a chain in order that I be bound to you every day of your life, for whatever you wish” (2007, 151). The gesture of sending a letter and “himself” in a portrait makes the king’s presence “doubly felt” (2007, 154). Garcilaso’s poem sent from a great distance is a kind of letter (as I explain below), containing his personal imprint within verbal tapestries so that he will “be bound” to the vicereine.

Inscribed within the fourth tapestry woven by the nymph Nise is a snapshot of special significance: the topography and cityscape of Toledo, “la más felice tierra de la España” [the happiest region of the whole of Spain] (1995, 200), where Garcilaso was born. The famous Tagus [“el claro Tajo”] (197), reified through ekphrasis, is pictured bathing the land, circling the mountain on which the old buildings of the imperial city stand majestically:

Pintado el caudaloso rio se vía,

que, en áspera estrecheza reducido,

un monte casi alrededor ceñía […]

Estaba puesta en la sublime cumbre

del monte, y desd’allí por él sembrada,

aquella ilustre y clara pesadumbre

d’antiguos edificios adornada.

[The mighty river in her picture’s seen

reduced at this point to a rocky narrows,

surrounding almost on all sides a mountain […]

Perched on the lofty brow of the great hill

and scattered down its slopes on every side,

was that incomparable and weighty pile,

with many an ancient edifice supplied.]

(201–3, 209–12)

The celebrated river irrigates the countryside “con artificio de las altas ruedas” [with the ingenious aid of water-wheels] (216). If not a self-portrait, Garcilaso sends the next best thing, a poignant material recollection of a place of origin. And more poignant still, now that both he and María are in foreign lands fulfilling Charles’s calling, the poet in the emperor’s army on the field of battle in Provence, the vicereine at the Neapolitan court in service to the imperial administration. That bit of nostalgia was announced in the eclogue’s dedicatory stanzas, where Garcilaso tells María about his longing for the homeland and for all that he holds dear, revealing early in the poem, albeit obliquely, his desire to connect with her at an intimate level: “la fortuna … / ya de la patria, ya del bien me aparta” [fortune … now separates me from my country, now from all that is good and safe] (17–19, my translation).

Roland Barthes’s well-known observation that “etymologically the text is a cloth; textus, from which text derives, means ‘woven’” (1979, 76), resonates in the eclogue with an almost literal sense: the nymphs are weavers, as is the poet, who “weaves” with words. This complementarity, anchored in the poem on the word “texer” [to weave], echoes an ancient link between text and textile. “[B]y the first century BCE [texere] no longer meant simply to weave or braid but could also mean to compose a work. From the first century CE on, the word textus took on its modern sense of ‘written text,’ yet it remained common in the lexicon of weaving: textor (weaver) … textum or textura (fabric or textile)” (Chartier 2007, 86). In the eclogue, “texer” appears both materially in the making of each tapestry (“lo que pinta / y texe cada ninfa” [what each nymph paints and weaves]) (117–18) and metaphorically in the speaker’s scriptural weaving, which combines pieces from ancient texts with fragments from contemporary Italian works to compose stories in the vernacular.12 A dramatic example is Eurydice’s death, where Garcilaso transforms and expands in implicit competition clipped renditions of scenes from Ovid and Virgil with rewritings of images from Ariosto’s Orlando furioso and Sannazaro’s Arcadia (Barnard 1987, 318–19).

John Schied and Jesper Svenbro write about this cross-cultural appropriation in Roman literature in terms of a textual “weaving” applicable to the eclogue:

When Catullus writes his poem on the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, his “weaving” has meaning connected to the occasion of the poem and the symbolism of the nuptial fabric, of course, but inevitably the poem-fabric also becomes a fabric on an “intercultural” level. It is a place where two cultures meet. And here, it is as if Catullus were using a Greek warp – the traditional basis for his poem – into which he introduces his own Latin woof, as if the best text were made of a Greek warp and a woof of Latin words. (1996, 145)

The nuptial fabric, a coverlet placed on the marriage bed of Peleus and Thetis, is inscribed with the story of Theseus and Ariadne (Catullus 1988, 64.50–264). Like the coverlet, the nymphs’ tapestries serve as a thematic occasion and symbol of the eclogue’s own textual fabric, the point at which cultures meet, a warp of Graeco-Roman mythology and Italian subtexts intersecting with a weft of Castilian words. Texts and textiles naturally call forth the instruments and the “authors” that produce them: the poet “weaving” his intercultural discursive cloth with a pen parallels the nymphs “writing” stories with a shuttle as pen.

In the sixteenth century, the needle was the primary female tool for composing narratives in fabrics, needlework being a sign of aesthetic virtuosity and even a way of making political statements, while the shuttle belonged to the exclusively male world of industrial production in tapestry workshops (Jones and Stallybrass 2000, 148–71, 94). The eclogue’s weaver-nymphs who “write” their stories with shuttles thus belong to a wholly literary tradition, a product of an ancient textual memory. They find precedents in the lovely Virgilian naiads of Georgics 4, who appear “spinning fleeces of Miletus, dyed with rich glassy hue” (1998, 334–5). Filódoce [Phyllodoce] and Climene [Clymene] are cited here by name (336, 345).13 Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a popular exemplar for literature and textiles in the sixteenth century, offer even closer antecedents, Philomela and Arachne, who narrate their stories with the shuttle as pen. The Ovidian tales, like those told by the eclogue’s nymphs, are violent narratives, and distinctive in that the mythological weavers, like the naiads, are eminently skilled. Philomela is raped by her brother-in-law, the Thracian king Tereus, who cuts off her tongue with his sword to silence her. Her tongue “faintly murmuring” on the dark earth (1984, 6.558) signals her alienation from speech. Weaving a tapestry for her sister Procne to read, a victim becoming a master in her telling, she chooses materials that represent the brutality of her rapist and her bloody mutilation: “She hangs a Thracian web [barbarica tela] on her loom, and skillfully weaving purple marks [purpureas notas] on a white background, she thus tells the story of her wrongs” (1984, 6.576–8; my emphasis). Lydian Arachne, for her part, after challenging Pallas Athena to a contest, weaves tales of deceit and seduction committed by the gods against mortals. Like the goddess, she works warp and weft with “well-trained hands” (6.60), deftly blending threads of gold (6.68) and Tyrian purple with lighter colours (6.61–2), details that resonate in the fabrics of the eclogue’s nymphs. Arachne’s tapestry is “flawless,” but she is punished for her presumption. Pallas strikes her with a shuttle and then, in pity, transforms her into a spider, the very emblem of her delicate art (6.129–45).

Garcilaso’s mingling of ancient and contemporary cultures, connecting as he does the world of luxurious textiles with classical myth reimagined within a court setting, finds a suggestive pictorial analogue a century later in Diego Velázquez’s recreation of the myth of Arachne in “Las hilanderas” (The Spinners, ca. 1655–60) (see fig. 4). In the painting’s foreground appear humble spinners working their wool.14 But what interests me here is the courtly scene in the brightly lit background, where Arachne and a helmeted Pallas Athena, similarly dressed, stand centre stage in front of a tapestry and, anachronistically, they are in the presence of three seventeenth-century aristocratic women in elegant clothing. The tapestry, which portrays the rape of Europa (one of the “celestial crimes” woven by Ovidian Arachne in her own tapestry), is a copy of Titian’s painting of the same subject, housed at the time in the royal collection at the Alcázar (Brown 1986, 252). Jonathan Brown notes that the tapestry is a homage to Titian, the favourite painter of Charles V and Phillip II. By “quoting” Titian, Velázquez celebrates painting as the noblest and most transcendent art: “Titian is equated with Arachne, and Arachne could ‘paint’ like a god” (Brown 1986, 253). Arachne, however, does not “paint”; she “weaves” like a god. If the tapestry is a homage to Titian the painter, as Brown suggests, it is a more distinctive homage to Arachne the weaver, who within Velázquez’s painterly fiction weaves her loom like Titian paints his canvas, implicitly with equal skill, reminiscent of Garcilaso’s weaver nymphs whose own artistry [artificio], as noted above, is celebrated by its identification with that of the Greek painters Apelles and Timanthes. Velázquez stages “[Titian’s] design into the more luxurious and costly world of textiles. Velázquez himself was keenly aware of the significance of textiles and of other costly goods in the production of the court and the courtier” (Jones and Stallybrass 2000, 102). The painter captures a social scene that could well have been the vicereine’s own at her Neapolitan court. A magnificent chamber of tapestries covers the walls (only the Europa and a strip of another hanging are visible) and the three finely dressed noblewomen admire the display, two of them chatting as in a typical court event. The vicereine, an admirer of tapestries and perhaps a collector in her own right, belonged to this world of luxury and magnificence, and by extension to the practice of the shuttle as a metaphorical pen. But, as we see next, she belonged also to the world of the actual pen and its special fabric, paper.

Figure 4 Diego Velázquez, Las hilanderas, ca. 1655–60. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Scala / Art Resource, NY.

The eclogue’s dedication is a rich discursive space containing another type of fabric and another occasion for praise and networking. Despite the poet’s Orphic voice celebrating the vicereine in two lines inspired by Virgil – “mas con la lengua muerta y fria en la boca / pienso mover la voz a ti debida” [for with the tongue cold and dead in my mouth / I aim to raise the voice I owe to you] (11–12) – it is the poet’s pen and its fabric, paper, that will record both voice and María’s fame. In the Virgilian source, Georgics 4.523–7 (1998), Orpheus’s head, torn from his body by the Maenads, floats down the Hebrus River, “its voice and death-cold tongue” singing the name of Eurydice, who was lost to the underworld. Recast in Garcilaso’s vernacular, the Latin fragment is animated for the self-representation of the lyric voice as an Orpheus figure and for a celebration that calls into action a magical act of memory. The tongue that gives birth to song belongs to the son of Calliope, the muse who possesses the gift of song, and the daughter of Mnemosyne, goddess of Memory. The new Orpheus in his own katabasis will use his voice to still the waters of oblivion, the river Lethe, in order to keep María’s presence alive in historical memory:

libre mi alma de su estrecha roca,

por el Estigio lago conducida,

celebrando t’irá, y aquel sonido

hará parar las aguas del olvido.

[my soul, when freed from its narrow prison

and ferried over the waters of the Styx,

will sing of you, and the sound it gives out then

will turn back the flood tide of oblivion.]

(13–16)

The poet further promises María that Apollo and the muses will bestow on him “ocio y lengua” [leisure (otium) and a tongue] to praise her (29–31, my translation). But María’s memory will be preserved not by the tongue, the instrument for composing song, but by pen and paper, the authorial tools for textual production. Garcilaso mentions in a typical recusatio how the duties of the soldier take him away from celebration through pen and paper: “y lo que siento más es que la carta / donde mi pluma en tu alabanza mueva, / poniendo en su lugar cuidados vanos, / (fortuna) me quita y m’arrebata de las manos” [and what troubles me most is that the page (paper) / my pen ought to be filling with your praise / (fortune) snatches from my hand … / replacing it with unprofitable cares] (21–4, my emphasis). But carta and pluma already had appeared implicitly at the beginning of the dedication, where the poet turns to epideictic, the rhetoric of praise, for an encomiastic “ilustre y hermosísima María” [illustrious and most beautiful María] (2). María, the wife of an eminent imperial official, was important in her own right in carrying the lineage of the marquisate of the Osorio Pimentel. Her official title was Marquise of Villafranca del Bierzo, which she brought to the viceroy by marriage. The pen is mentioned once again in the memorable “tomando ora la espada, ora la pluma” [taking up now the sword and now the pen] (40, my emphasis) in the field of battle, where Garcilaso writes his textual gift to María. The self-conscious staging of pen and paper (“carta” means paper, according to its Italian or Latin etymology [Morros 1995, 225]) against song and voice illustrates what Roger Chartier sees as a major concern of the period, the desire to record what was in danger of obliteration:

[S]ocieties of early modern Europe … preserved in writing traces of the past, remembrances of the dead, the glory of the living, and texts of all kinds that were not supposed to disappear. Stone, wood, fabric, parchment, and paper all served as substrates on which the memory of events and men could be inscribed. In the open space of the city or the seclusion of the library, in majesty, in books or in humility on more ordinary objects, the mission of the written was to dispel the obsession with loss. (2007, vii)

Understood in this context, Garcilaso’s written word rescues the vicereine from the instability of commemoration through voice and song.15 Her memory is materialized, inscribed by the author’s quill on the surface of the paper – a kind of fabric made from linen and cotton rags – then printed in the ubiquitous chap-books [pliegos sueltos], and ultimately in a book.

The tension between oral and written discourses reminds us that the lyric speaker is the product of a written culture. And if he is a writer, the vicereine is above all a reader, and if carta is understood to mean letter as well as paper, the eclogue acts as an epistle, sophisticated and erudite in its classical import, sent from afar to be read in the privacy of her chambers. Placed in the world of learning and the pen, where she is lauded for her beauty and high worth [valor], María is also praised for her “ingenio” [ingenium] (3–4), meaning here intelligence and excellence of mind, traits customarily reserved for men, as in “hombre doctor y de ingenio agudo” [a learned man of acute intellect] (Diccionario de Autoridades). This is not the first time that Garcilaso flatters a woman for her intellectual acumen. In his letter-prologue to Boscán’s translation of Castiglione’s Il Cortegiano, he similarly flatters Jerónima Palova de Almogávar, following the example of Giuliano de’ Medici, who in his defence of the donna di palazzo [the court lady], calls on her to assume the virtues of the male courtier, among them wit and “knowledge of letters” (1959, 3.211). Garcilaso praises Jerónima’s courtly virtues, including her intellectual qualities: the poet assures her that the book she convinced Boscán to translate is worthy of being in her hands [“merece andar en vuestras manos”] (Boscán 1994, 75), that is, it is worthy of being read by her, its success now guaranteed by virtue of her very reading.

Garcilaso’s praise runs counter to the conduct manuals that advised women to shun learned texts and the pen in favour of religious books and the needle as signs of virtue. In his Árbol de consideración y varia doctrina (Tree of consultation and varied teaching, 1548), the canon Pedro Sánchez writes about this feminine ideal of behaviour: “She should pray devotedly with a rosary and if she knows how to read, she should read devotional books and books of good doctrine, for writing must be left to men. She should know how to use a needle well and how to use a spindle and distaff, having no need for the use of a pen” (cited in Bouza 1999, 60). Garcilaso distances himself from this type of moral preaching as well as from counter prescriptions of court poets like Ariosto who, seeking patronage from noblewomen, reversed the preference for textiles over writing in his Orlando furioso, praising instead “the women poets of Italy for leaving ‘the needle and the cloth’ for the fountain of Aganippe on Parnassus, proving that Italy could produce more poets like Vittoria Colonna” (Jones and Stallybrass 2000, 142). Garcilaso does a double turn. While placing María as participant and spectator in the nymphs’ world of the needle and the shuttle, the poet locates her as well in the erudite world of the pen, as a reader for a distinctive act of networking. If we recall Barthes’s observation, mentioned above, that “etymologically the text is a cloth” (1979, 76), and that networking in its own etymology points to the enterprise of fabric-making in cloth – “work in which threads … or similar materials are arranged in the fashion of a net; especially a light fabric made of netted thread” (OED) – text, textile, and networking become fused for a celebratory inscription of the writer as a poet-craftsman, and in his flattery and praise of the vicereine, he joins Castiglione’s courtier as a skilled performer of court manoeuvres. In writing his tapestries, Garcilaso celebrated himself no less than Charles V in the tapestries that celebrate his triumph at the Battle of Pavia (1525) or the Conquest of Tunis (1535), where as a participant in the campaign, the poet may well have witnessed the artist Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen drawing scenes that would serve as the basis of cartoons for these hangings.

Garcilaso’s reassuring identity crafted in artifice and networking within a tapestry culture, however, is not the whole story, for the violent narratives complicate the configuration of an identity based squarely on these cloths as gifts. Another poetic self emerges: a vulnerable one centred on “lengua,” Orpheus’s tongue, the bodily organ that is the locus and emblem of voice and song. Speaking from a severed head swirling down the Hebrus, Orpheus’s tongue stands for both the power of voice and its fragility. Thus its restaging in the eclogue, as the lyric I appropriates it to become an inspired verbal artist, involves a double movement: the tongue that sings María and the tapestries also conjures up an act of precarious voicing that culminates in the fourth tapestry, the scene of the decapitated Elisa and her epitaph, written by a mourning nymph on the bark of a poplar tree, whose letters speak on her behalf, “que hablaban ansí por parte della” (240):

“Elisa soy, en cuyo nombre suena

y se lamenta el monte cavernoso,

testigo del dolor y grave pena

en que por mí se aflige Nemoroso

y llama: ‘Elisa,’ ‘Elisa’; a boca llena

responde el Tajo, y lleva presuroso

al mar de Lusitania el nombre mío,

donde será escuchado, yo lo fío.”

[“Elisa am I, and to my unlucky name

the cave-infested mountain echoes and moans,

witness to the grief, the overwhelming pain

Nemoroso must suffer on my account:

‘Elisa,’ he calls out, and ‘Elisa’ again

Tagus intones, as it rushes swiftly on,

bearing my name to the Lusitanian sea,

to where it will be heard, I can safely say.”]

(241–8)

The pastoral convention of carving letters on bark shares in the practice of carving inscriptions on funerary monuments designed to preserve the memory of the dead in stone.16 The eclogue’s epitaph, incised on wood as if on a tombstone, preserves the memory of Elisa in a public space, addressed to a literate pastoral community, the shepherds being, as the genre dictated, courtiers in disguise. If the memory of the vicereine is directly inscribed and preserved on paper [carta], that of the dead Elisa is inscribed and preserved on multiple surfaces: the epitaph’s words are carved on wood and recorded by Nise on cloth, in the manner of a tapestry’s cartouche, which the poet transcribes onto paper. And yet, encased en abîme within these material objects, Elisa’s voice, which had been ventriloquized by the epitaph’s “speaking” letters, betrays a profound fragility as it recedes into a polyphony of voices, with first the mountain, then Nemoroso, and finally the Tagus echoing her name. Elisa’s name becomes a disarticulated utterance mirroring her decapitation. Orpheus’s decapitation by the Maenads and their scattering of his body parts, present subtextually, strengthens the sense of violence and vulnerability. Chartier argues that one of the missions of the written is to preserve “remembrances of the dead” (2007, vii), as is the case here. Nise’s purpose in weaving her tapestry is to make known Elisa’s “lamentable cuento” [dreadful tale] (257) on land and beyond:

quiso que de su tela el argumento

la bella ninfa muerta señalase

y ansí se publicase de uno en uno

por el húmido reino de Neptuno.

[she had planned that the subject of her tapestry

would single out the beautiful dead nymph,

so that from mouth to mouth the news relayed

should fill the humid realm where Neptune reigned.]

(261–4)

What is “published” in the tapestry – and recorded by the poet – is not only the news of Elisa’s death, but the loss of a beautiful woman through violent death: the decapitated body of the delicate nymph lying like a white swan among the grass and flowers (229–32).

A fragile, personal lament is thus projected through the mediating screen of the tapestry, a space where figures take on bits of discourse, which stand for a disguised lyric self-reflection. In the eclogue, Garcilaso offers María another memorable gift, a vulnerable self, the voice of loss, now encased in a lovely weaving: an intimate gesture from a soldier skilled with the sword that decapitates and a poet whose pen captures decapitation intrinsic to both war and eros.

1 On Renaissance tapestries, see in particular Campbell (2002, 2007), Delmarcel (1999, 2000), Thomson (1973, 189–276), and Balis, et al. (1993).

2 On the identity of María, see Keniston (1922, 255–8).

3 Garcilaso was sent into exile for having acted as a witness to the marriage of his brother Pedro’s son to Isabel de la Cueva, heiress of the Duchy of Alburquerque. The duke and other members of the family opposed the marriage. Charles sent a cédula (4 September 1531) from Flanders to the empress urging her to prevent it. It was too late. Garcilaso was finally punished and sent to an island in the Danube, but later was allowed to serve his exile in Naples. For further details, see Keniston (1922, 103–16) and Morros (1995, xxxiv–xxxv).

4 Spain had a thriving industry of fine cloth weavings in silk, gold, and silver threads (especially in Granada, Toledo, Cordoba, Seville, and Valencia), as well as embroidery in particular for the nobility and church. Toledo at one point had thirteen thousand telares. However, there was no significant tapestry industry that could compete with the Flemish and the French until the establishment of the Real Fábrica de Tapices (first known as the Fábrica de Tapices de Santa Bárbara) by Philip V in the eighteenth century (Sánchez Cantón 1950, 105, and Junquera 1985, 49). For details on the tapestry industry in Spain, see Junquera (1985, 43–9) and Herrero Carretero, “Tapicería” (133–201), in Bartolomé Arraiza (1999). On embroideries and other weavings in fine cloth, see Martín I Ros, “Tejidos” (9–80), and González Mena, “Bordado y encaje eruditos” (83–130), both in Bartolomé Arraiza (1999). There is some evidence that Garcilaso was a consumer of “tejidos.” Aurora Egido (2003, 187) reminds us that in his last will and testament, the poet includes the following: “Debo a Castillo, tejedor de oro tirado, vecino de Toledo, veinte mil maravedís” [I owe Castillo, a resident of Toledo and weaver in gold threads, twenty thousand maravedis]. The citation comes from Morros (1995, 285), who identifies the weaver as Bartolomé Castillo (d. 1550).

5 On Maximilian’s staging of images – including books, medals, armour, and a tomb monument – to enhance his authority and spread his imperial ideology, see Silver (2008). On the famous set of commemorative woodcuts commissioned by Maximilian, see Appelbaum (1964).

6 All citations from Garcilaso’s poetry come from Morros’s edition (1995). Translations are from Dent-Young (2009), unless otherwise indicated.

7 This inventory of the viceroy’s possessions records a number of tapestry chambers, including several based on mythological or classical themes (seven tapestries woven in silk and gold of the legend of Paris and Helen, two on Vulcan, ten on Lucretia, and six on Romulus and Remus). Others were listed by genre, millefleurs (“verdura”) appearing among other types, such as “ystoria” [history], “figuras” [figures], and many with religious themes (Hernando Sánchez 1993, 51).

8 For a discussion of the relation between weaving and painting in the eclogue within the context of the visual language of ekphrasis and the rhetoric of enargeia as conceived by Erasmus, following Quintilian, see Barnard (1992). On artistic dimensions of the eclogue, see also Bergmann (1979), Paterson (1977), and Rivers (1962). See Barnard (1992) on the interrelation between weaving and writing, which I expand upon below. Aurora Egido (2003) makes important observations on this dual enterprise, especially on the double meaning of the word “tinta,” purple dye as well as ink (188, n.19).

9 For details on this request, made in a letter dated 1 September 1534, see Lumsden (1952). In a second letter, dated 20 January 1535, Pedro asks the emperor for the postponement of a suit Garcilaso had brought against the powerful Mesta, a request that was denied (Keniston 1922, 131).

10 Mauss extended his observations on gift-giving to ancient Rome, India, and Germany, inviting by implication further inquiry into this cultural practice in other areas and periods. For studies tailoring Mauss to practices in the early modern period, see in particular Davis (2000), Klein (1997), Shephard (2010), and Warwick (1997).

11 Using Mauss as a point of departure, Lisa Klein has examined gift-giving customs at the court of Elizabeth I. Among Klein’s examples is the gift presented to the queen by Elizabeth Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury, whose dynastic ambitions in marrying her daughter to the son of Mary Stuart’s mother-in-law, Charles Stuart, made the queen suspect the countess’s loyalty. The countess presented a “hand-wrought” gift, an embroidered cloak chosen and designed for Elizabeth to reassure the queen of her “love and fidelity.” The gift was memorable, as “the color, trimming, and expense” of the cloak called forth Elizabeth’s praise and “promises of continued favor” (1997, 472). Sánchez Cantón (1950, 92–5) comments on gifts of tapestries made by family and friends to Isabella of Castile, which though not “hand-wrought” by the donors were evidently offered to establish personal bonds with the queen, as noted in the formulaic inscription in the royal register: “dado para servicio de su Alteza” [given in service to her Majesty] (92). Among these are the gifts of the Marquesa de Moya, “fidelísima amiga y servidora” [most loyal friend and servant] (92–3) and the small tapestry given by the treasurer, Rui López, “muy rico, con oro e alguna plata” [very rich, with gold and some silver] (94).

12 On models, see Morros’s extensive notes (1995, 230–7, 518–26). See also, in particular, Cruz (1988, 106–22) and Lapesa (1985, 158–66), who stress an ars combinatoria; Fernández-Morera (1982, 73–100), who focuses especially on the Virgilian sources; and Navarrete (1994, 124–5), who singles out Castiglione’s notion of sprezzatura as the basis of Garcilaso’s “graceful, seemingly artless” lyric.

13 Following Virgil, Sannazaro in his Arcadia has nymphs weave tapestries, including one with the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, which Garcilaso uses as a model (1966, 12.136).

14 For various interpretations of the spinners in the foreground, including the old woman as Athena herself, see Jones (1996, 205–6) and Welles (1986, 149–50).

15 In his discussion of the Orphic allusion, Paul Julian Smith suggests that “while Garcilaso appears to appeal to ‘voice’ as authentic, eternal utterance, he knows that the preservation of that voice is dependent on its duplication by the written word” (1988, 52). Egido offers a similar interpretation (2003, 185), adding that pen and paper are the true protagonists, part of “la poética de una laudatio que convierte el acto de escribir en una empresa heroica y, a la par, en un acto de entrega amorosa” [a poetics of celebration that converts the act of writing into a heroic enterprise and, at the same time, into an act of amorous surrender] (185). In Egido’s reading, María represents the beloved.

16 Armando Petrucci documents this graphic culture in early modern Italy, which had its antecedents in ancient epigraphic practices (1993, 16–61). Petrucci offers numerous examples of tombstones, including the one erected by Giovanni Pontano in Naples in memory of his wife, Adriana, with inscriptions imitating classical lettering on its facade and flanks (1993, 22). Garcilaso may have seen it, along with other epigraphic funerary monuments, during his stay in the city.

Appelbaum, Stanley, ed. and trans. 1964. The Triumph of Maximilian I: 137 Woodcuts by Hans Burgkmair and Others. New York: Dover.

Balis, Arnout, et al. 1993. Les Chasses de Maximilien. Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux.

Barnard, Mary E. 1987. “Garcilaso’s Poetics of Subversion and the Orpheus Tapestry.” PMLA 102 (3): 316–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/462479.

Barnard, Mary E. 1992. “Correcting the Classics: Absence and Presence in Garcilaso’s Third Eclogue.” Revista de Estudios Hispánicos 26: 3–20.

Barthes, Roland. 1979. “From Work to Text.” In Textual Strategies: Perspectives in Post-Structuralist Criticism, edited by Josué V. Harari, 73–81. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Bartolomé Arraiza Alberto, ed. 1999. Artes decorativas II. In Summa Artis: Historia general del arte 45. Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

Bergmann, Emilie. 1979. Art Inscribed: Essays on Ekphrasis in Spanish Golden Age Poetry. Harvard Studies in Romance Languages 35. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Boscán, Juan, trans. 1994. El cortesano. Edited by Mario Pozzi. Madrid: Cátedra.

Bouza, Fernando. 1999. Communication, Knowledge, and Memory in Early Modern Spain. Translated by Sonia López and Michael Agnew. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bouza, Fernando. 2007. “Letters and Portraits: Economy of Time and Chivalrous Service in Courtly Culture.” In Correspondence and Cultural Exchange in Europe, 1400–1700, edited by Francisco Bethencourt and Florike Egmond, 145–62. Vol. 3 of Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe, edited by Robert Muchembled and William Monter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, Jonathan. 1986. Velázquez: Painter and Courtier. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Campbell, Thomas P. 2002. Tapestry in the Renaissance: Art and Magnificence. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press.

Campbell, Thomas P. 2007. Henry VIII and the Art of Majesty: Tapestries at the Tudor Court. New Haven: Published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press.

Castiglione, Baldassare. 1959. The Book of the Courtier. Translated by Charles S. Singleton. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Catullus. 1988. “The Poems of Gaius Valerius Catullus.” In Catullus, Tibullus, and Pervigilium Veneris. Translated by F.W. Cornish. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chartier, Roger. 2007. Inscription and Erasure: Literature and Written Culture from the Eleventh to the Eighteenth Century. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Cruz, Anne J. 1988. Imitación y transformación: El petrarquismo en la poesía de Boscán y Garcilaso de la Vega. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Davis, Natalie Zemon. 2000. The Gift in Sixteenth-Century France. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Delmarcel, Guy. 1999. Flemish Tapestries. New York: Harry Abrams.

Delmarcel, Guy. 2000. Los Honores: Flemish Tapestries for the Emperor Charles V. Translated by Alastair Weir. [Antwerp]: SDZ / Pandora.

Dent-Young, John, ed. and trans. 2009. Selected Poems of Garcilaso de la Vega: A Bilingual Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Diccionario de Autoridades. 1984. Facsimile edition. Madrid: Gredos.

Egido, Aurora. 2003. “El tejido del texto en la Égloga III de Garcilaso.” In Garcilaso y su época: del amor y la guerra, edited by María Díez Borque José and Luis Ribot García, 179–200. Madrid: Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales.

Fernández-Morera, Darío. 1982. The Lyre and the Oaten Flute: Garcilaso and the Pastoral. London: Tamesis.

Garcilaso de la Vega. 1995. Garcilaso de la Vega: Obra poética y textos en prosa. Edited by Bienvenido Morros. Barcelona: Crítica.

González Mena, María Angeles. 1999. “Bordado y encajes eruditos,” 83–130. See Bartolomé Arraiza.

Guiffrey, Jules. 1878. Tapisseries françaises. Vol. 1, Pt. 1 in Histoire générale de la tapisserie, 1878–1885. Edited by Jules Guiffrey, Eugène Müntz, and Alexander Pinchart. 3 vols. Paris: Société Anonyme de Publications Périodiques.

Hernando Sánchez, Carlos José. 1993. “La vida material y el gusto artístico en la Corte de Nápoles durante el renacimiento: El inventario de bienes del Virrey Pedro de Toledo.” Archivo español de arte 66 (261): 35–55.

Herrero Carretero, Concha. 1999. “Tapicería,” 133–201. See Bartolomé Arraiza.

Jones, Ann Rosalind. 1996. “Dematerializations: Textile and Textual Properties in Ovid, Sandys, and Spenser.” In Subject and Object in Renaissance Culture, edited by Margreta de Grazia, Maureen Quilligan, and Peter Stallybrass, 189–209. Cambridge Studies in Renaissance Literature and Culture 8. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jones, Ann Rosalind, and Peter Stallybrass. 2000. Renaissance Clothing and the Materials of Memory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Junquera, Juan José. 1985. Tapisserie de Tournai en Espagne: La tapisserie bruxelloise en Espagne au XVI e siècle. Tournai-Brussels-Rijkhoven: Europalia.

Junquera de Vega, Paulina. 1970. “Tapices de los reyes católicos y de su época.” Reales Sitios 26: 16–26.

Keniston, Hayward. 1922. Garcilaso de la Vega: A Critical Study of His Life and Works. New York: Hispanic Society of America.

Kettering, Sharon. 1988. “Gift-Giving and Patronage in Early Modern France.” French History 2 (2): 131–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/fh/2.2.131.

Klein, Lisa M. 1997. “Your Humble Handmaid: Elizabethan Gifts of Needlework.” Renaissance Quarterly 50 (2): 459–93. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3039187.

Lapesa, Rafael. 1985. La trayectoria poética de Garcilaso. 3rd ed. Rev. In Garcilaso: Estudios completos. Madrid: Istmo.

Lumsden, Audrey. 1952. “Garcilaso and the Chatelainship of Reggio.” Modern Language Review 47 (4): 559–60. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3719711.

Martín I Ros, Rosa M. 1999. “Tejidos,” 9–80. See Bartolomé Arraiza.

Mauss, Marcel. 1990. The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. Translated by W.D. Halls. New York: Norton.

McLean, Paul D. 2007. The Art of the Network: Strategic Interaction and Patronage in Renaissance Florence. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Morros, Bienvenido. 1995. See Garcilaso de la Vega.

Navarrete, Ignacio. 1994. Orphans of Petrarch: Poetry and Theory in the Spanish Renaissance. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ovid. 1984. Metamorphoses. 2 vols. Edited and translated by Frank Justus Miller. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Panofsky, Erwin. 1951. “‘Nebulae in Pariete’: Notes on Erasmus’ Eulogy on Dürer.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 14 (1/2): 34–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/750351.

Paterson, Alan K.G. 1977. “Ecphrasis in Garcilaso’s ‘Egloga Tercera.’” Modern Language Review 72 (1): 73–92. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3726297.

Petrucci, Armando. 1993. Public Lettering: Script, Power, and Culture. Translated by Linda Lappin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rivers, Elias L. 1962. “The Pastoral Paradox of Natural Art.” MLN 77 (2): 130–44. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3042857.

Sánchez Cantón, Francisco Javier. 1950. Libros, tapices y cuadros que coleccionó Isabel la Católica. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

Sannazaro, Jacopo. 1966. Arcadia and Piscatorial Eclogues. Translated by Ralph Nash. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Schied, John, and Jesper Svenbro. 1996. The Craft of Zeus: Myths of Weaving and Fabric. Translated by Carol Volk. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shephard, Tim. 2010. “Constructing Identities in a Music Manuscript: The Medici Codex as a Gift.” Renaissance Quarterly 63 (1): 84–127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/652534.

Silver, Larry. 2008. Marketing Maximilian: The Visual Ideology of a Holy Roman Emperor. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Smith, Paul Julian. 1988. Writing in the Margin: Spanish Literature of the Golden Age. Oxford: Clarendon.

Spitzer, Leo. 1952. “Garcilaso, Third Eclogue, Lines 265–271.” Hispanic Review 20 (3): 243–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/470708.

Thomson, W.G. 1973. A History of Tapestry from the Earliest Times until the Present Day. 3rd ed. Rev. F.P. and E.S. Thomson. East Ardsley, Eng.: EP Publishing.

Vasari, Giorgio. 1996. Lives of the Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Translated by Gaston du C. de Vere. 2 vols. New York: Knopf.

Virgil. 1998. Eclogues. Georgics. Aeneid. The Minor Poems. Edited and translated by H. Rushton Fairclough. Rev. G.P. Goold. 2 vols. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Warwick, Genevieve. 1997. “Gift Exchange and Art Collecting: Padre Sebastiano Resta’s Drawing Albums.” Art Bulletin 79 (4): 630–46. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3046279.

Welles, Marcia L. 1986. Arachne’s Tapestry: The Transformations of Myth in Seventeenth-Century Spain. San Antonio, TX: Trinity University Press.